歌詞

Lyrics

☆ 歌詞とは、通常、節とコーラスから構成される楽曲を構成する言葉である。歌詞の作者は作詞家である。しかし、オペラのような長編の楽曲の歌詞は通常「リブ レット」と呼ばれ、その作者は「リブレット作家」と呼ばれる。ラップやグライムには、韻を踏んだ言葉(韻を踏む言葉のバリエーションが多い)が用いられ、 歌うというよりもリズムに乗せて話すように歌われる。歌詞の意味は、明示的であることもあれば、暗示的であることもある。歌詞の中には抽象的でほとんど意 味不明なものもあるが、そのような場合、その解釈では、形式、アーティキュレーション、韻律、表現の対称性が強調される。

| Lyrics are words

that make up a song, usually consisting of verses and choruses. The

writer of lyrics is a lyricist. The words to an extended musical

composition such as an opera are, however, usually known as a

"libretto" and their writer, as a "librettist". Rap songs and grime

contain rap lyrics (often with a variation of rhyming words) that are

meant to be spoken rhythmically rather than sung. The meaning of lyrics

can either be explicit or implicit. Some lyrics are abstract, almost

unintelligible, and, in such cases, their explication emphasizes form,

articulation, meter, and symmetry of expression. |

歌詞とは、通常、節とコーラスから構成される楽曲を構成する言葉であ

る。歌詞の作者は作詞家である。しかし、オペラのような長編の楽曲の歌詞は通常「リブレット」と呼ばれ、その作者は「リブレット作家」と呼ばれる。ラップ

やグライムには、韻を踏んだ言葉(韻を踏む言葉のバリエーションが多い)が用いられ、歌うというよりもリズムに乗せて話すように歌われる。歌詞の意味は、

明示的であることもあれば、暗示的であることもある。歌詞の中には抽象的でほとんど意味不明なものもあるが、そのような場合、その解釈では、形式、アー

ティキュレーション、韻律、表現の対称性が強調される。 |

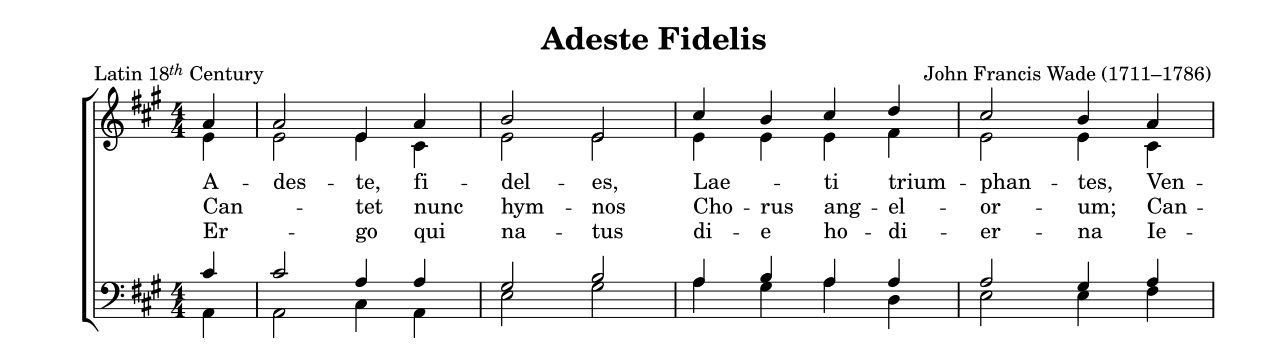

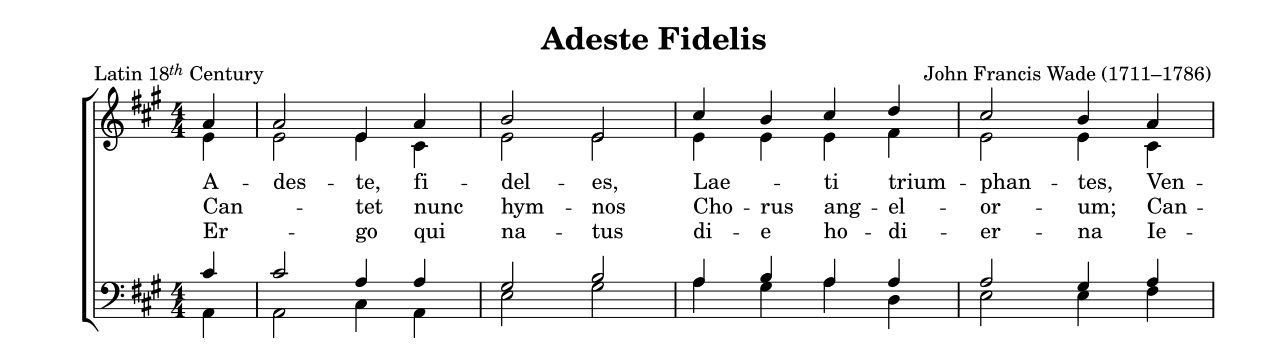

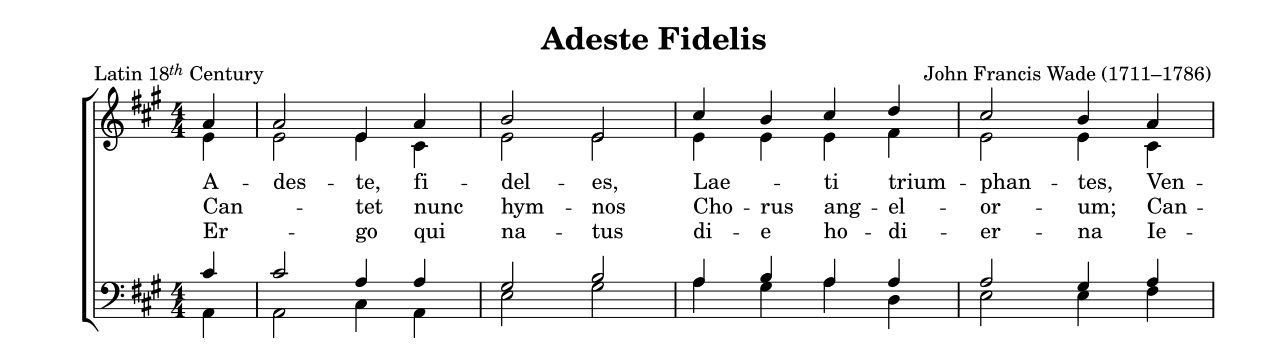

Lyrics in sheet music. This is a homorhythmic (i.e., hymn-style) arrangement of a traditional piece entitled "Adeste Fideles" (the original Latin lyrics to "O Come, All Ye Faithful") in standard two-staff format for mixed voices. |

楽譜の歌詞。これは、伝統的な楽曲「アデステ・フィデレス」(「O Come, All Ye Faithful」の原語ラテン語歌詞)をホモリズミック(賛美歌風)にアレンジした、混声合唱用の標準的な2パート譜である。(→欄外にYouTube 映像) |

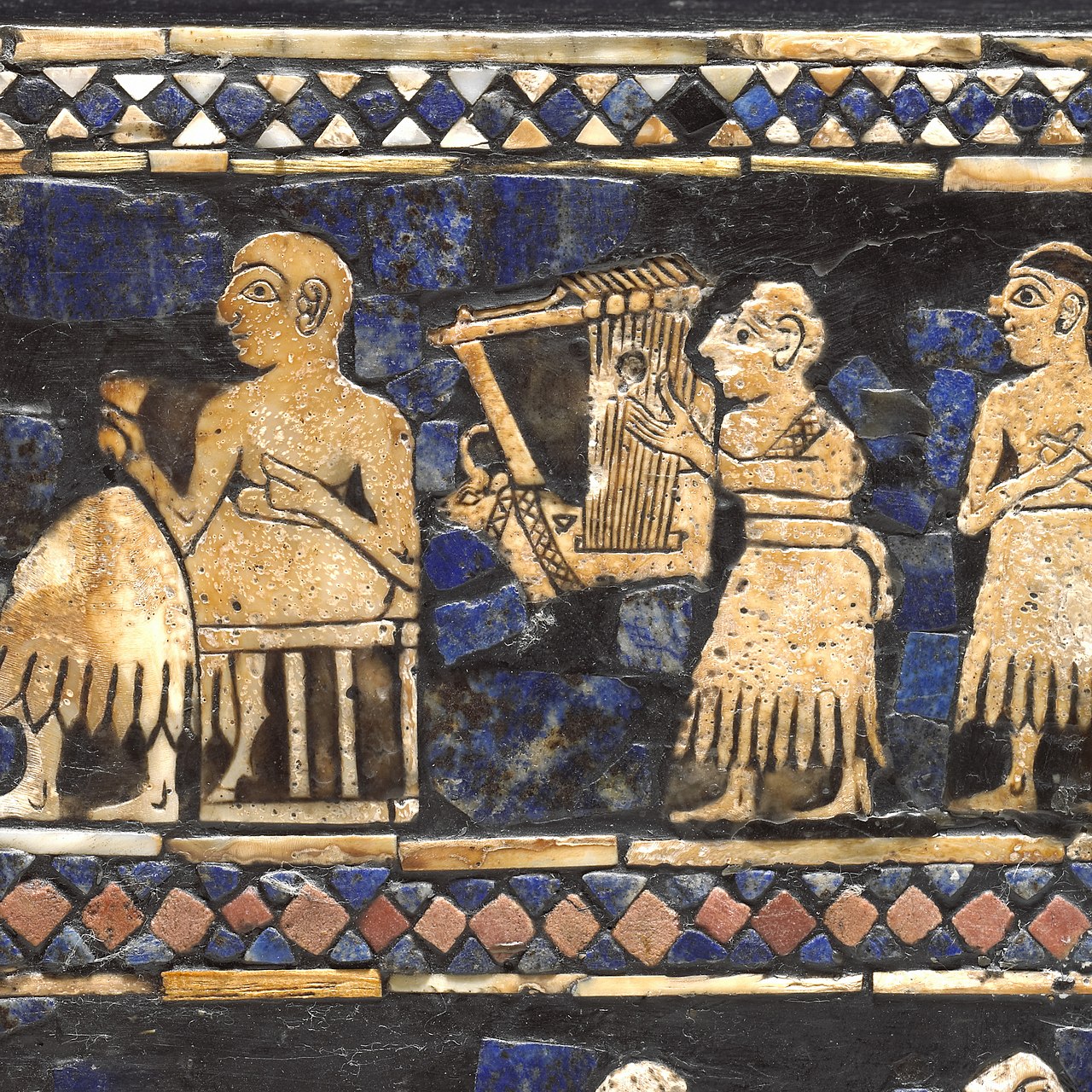

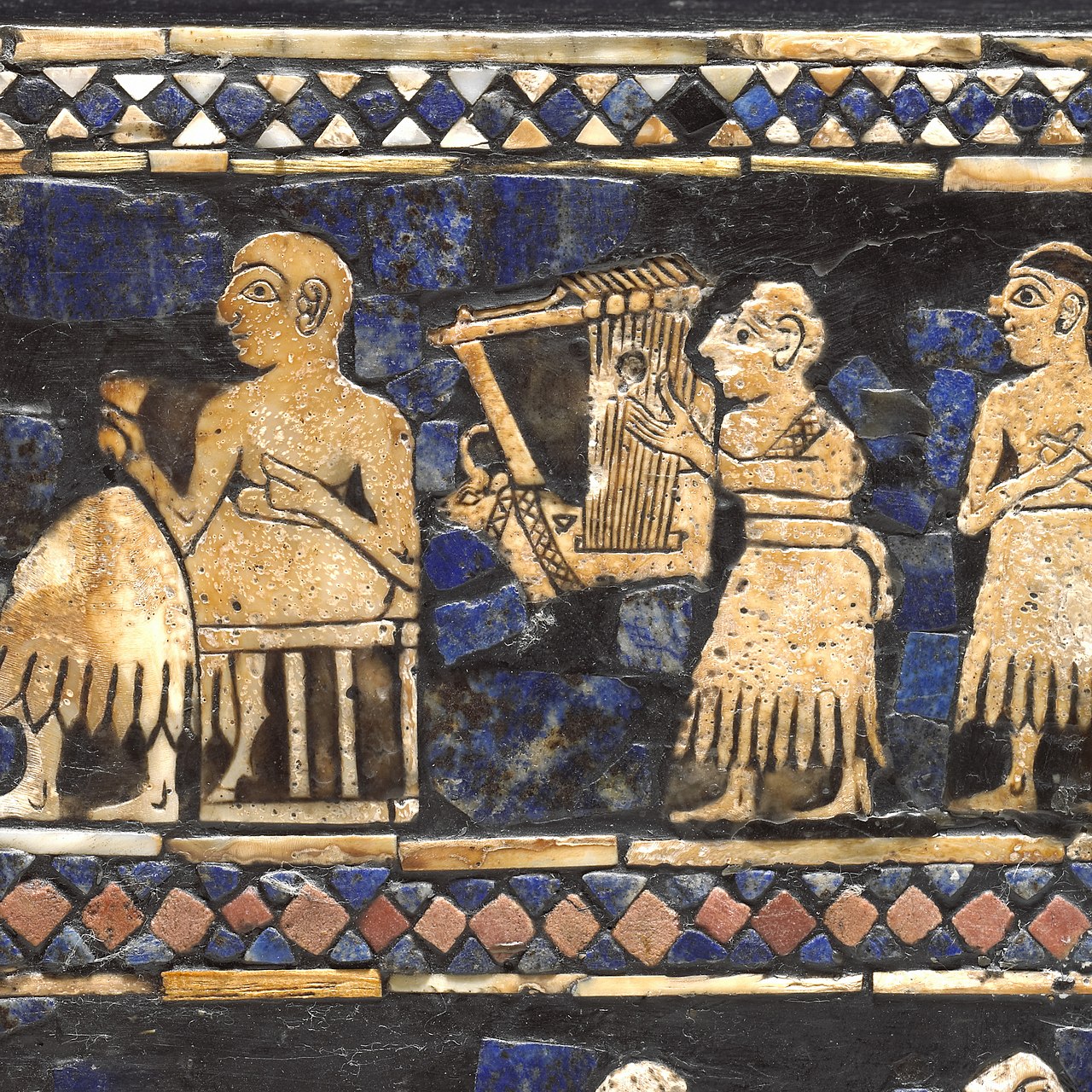

Etymology A lyrist on the Standard of Ur, c. 2500 BC The word lyric derives via Latin lyricus from the Greek λυρικός (lurikós),[1] the adjectival form of lyre.[2] It first appeared in English in the mid-16th century in reference to the Earl of Surrey's translations of Petrarch and to his own sonnets.[3] Greek lyric poetry had been defined by the manner in which it was sung accompanied by the lyre or cithara,[4] as opposed to the chanted formal epics or the more passionate elegies accompanied by the flute. The personal nature of many of the verses of the Nine Lyric Poets led to the present sense of "lyric poetry" but the original Greek sense of "lyric poetry"—"poetry accompanied by the lyre" i.e. "words set to music"—eventually led to its use as "lyrics", first attested in Stainer and Barrett's 1876 Dictionary of Musical Terms.[5] Stainer and Barrett used the word as a singular substantive: "Lyric, poetry or blank verse intended to be set to music and sung". By the 1930s, the present use of the plurale tantum "lyrics" had begun; it has been standard since the 1950s for many writers.[1] The singular form "lyric" is still used to mean the complete words to a song by authorities such as Alec Wilder,[6] Robert Gottlieb,[7] and Stephen Sondheim.[8] However, the singular form is also commonly used to refer to a specific line (or phrase) within a song's lyrics. |

語源 紀元前2500年頃のウルスタンダードのリリシスト リリックという語は、ギリシャ語のλυρικός(lurikós)からラテン語のlyricusを経て派生したものであり、[1] これは竪琴の形容詞形である。[2] この語は16世紀半ばに初めて英語で登場し、サーリー伯によるペトラルカの翻訳と彼自身のソネットを指して用いられた。[3] ギリシャのリリック詩は、竪琴またはキタラの伴奏で歌われる方法によって定義されていた。[4] 詠唱される形式的な叙事詩や、フルート伴奏の情熱的な哀歌とは対照的である。九人の抒情詩人」の詩の多くが持つ人格的な性質が、現在の「抒情詩」の感覚に つながったが、ギリシャ語の「抒情詩」の本来の意味である「竪琴の伴奏による詩」すなわち「音楽にのせて歌われる言葉」は、最終的に「歌詞」としての使用 につながった。この用法は、1876年のステイナーとバレットによる『音楽用語辞典』で初めて確認されている。ステイナーとバレットは、この語を単数形の 「音楽にのせて歌われることを意図した詩、詩歌、または空白の韻文」という意味で、単数形の 1930年代には、現在のように「歌詞」という単数形が使われ始めた。1950年代以降、多くの作家の間で標準的な用法となっている。[1]単数形「リ リック」は、アレック・ワイルダー(Alec Wilder)、ロバート・ゴットリーブ(Robert Gottlieb)、スティーヴン・ソンドハイム(Stephen Sondheim)などの権威者によって、楽曲の歌詞全体を意味するものとして現在でも使用されている。[6][7][8]しかし、単数形は、楽曲の歌詞 の中の特定の行(またはフレーズ)を指す場合にも一般的に使用されている。(またはフレーズ)を指す場合にも |

| Poems This section possibly contains original research. Please improve it by verifying the claims made and adding inline citations. Statements consisting only of original research should be removed. (March 2008) (Learn how and when to remove this message) The differences between poem and song may become less meaningful where verse is set to music, to the point that any distinction becomes untenable. This is perhaps recognised in the way popular songs have lyrics. However, the verse may pre-date its tune (in the way that "Rule Britannia" was set to music, and "And did those feet in ancient time" has become the hymn "Jerusalem"), or the tune may be lost over time but the words survive, matched by a number of different tunes (this is particularly common with hymns and ballads). Possible classifications proliferate (under anthem, ballad, blues, carol, folk song, hymn, libretto, lied, lullaby, march, praise song, round, spiritual). Nursery rhymes may be songs, or doggerel: the term does not imply a distinction. The ghazal is a sung form that is considered primarily poetic. See also rapping, roots of hip hop music. Analogously, verse drama might normally be judged (at its best) as poetry, but not consisting of poems (see dramatic verse). In Baroque music, melodies and their lyrics were prose. Rather than paired lines they consist of rhetorical sentences or paragraphs consisting of an opening gesture, an amplification (often featuring sequence), and a close (featuring a cadence); in German Vordersatz-Fortspinnung-Epilog.[9] For example: When I was a child, [opening gesture] I spoke as a child, [amplification...] I understood as a child, [...] I thought as a child; [...] But when I became a man, I put away childish things. [close] - 1 Corinthians 13:11 |

詩 この節には、おそらく独自の研究が含まれている。主張を検証し、インライン引用を追加することで、それを改善してください。独自の研究のみで構成される記 述は削除すべきである。 (2008年3月) (このメッセージの削除方法およびタイミングについては、こちらをご覧ください) 詩に音楽がつけられる場合、詩と歌の違いはあまり意味を持たなくなる。その違いは、区別することが不可能になるほどである。これは、おそらくポピュラーソ ングの歌詞のつけられ方で認識されている。 しかし、曲が詩より先に存在することもあり(「Rule Britannia」が曲がつけられ、「And did those feet in ancient time」が賛美歌「Jerusalem」となったように)、また、曲は時とともに失われても、言葉は生き残り、異なる曲と組み合わされることもある(こ れは特に賛美歌やバラードでよく見られる)。 分類の可能性は増大している(国歌、バラード、ブルース、キャロル、フォークソング、賛美歌、リブレット、リート、子守唄、行進曲、賛美歌、輪唱、スピリ チュアル)。 童謡は歌であるかもしれないし、駄句であるかもしれない。この用語は区別を意味しない。 ガザルは主に詩的とされる歌の形式である。 ヒップホップ音楽のルーツであるラップも参照。 同様に、通常、詩劇は(最高のものであっても)詩とはみなされないが、詩で構成されているわけではない(劇詩を参照)。 バロック音楽では、メロディとその歌詞は散文であった。対になった行ではなく、修辞的な文章や段落で構成されており、導入部、展開部(しばしば順序を特徴 としている)、結尾(終止を特徴としている)から成る。ドイツ語では、Vordersatz-Fortspinnung-Epilogである。[9] 例えば、 私が子供の頃、[導入部] 私は子供らしく話し、[増幅...] 私は子供らしく理解し、[...] 子供らしく考えた。[...] しかし、私が大人になったとき、子供らしいものは捨てた。[終結] - コリント人への手紙 第一 13:11 |

| Shifter In the lyrics of popular music a "shifter"[10] is a word, often a pronoun, "where reference varies according to who is speaking, when and where",[11] such as "I", "you", "my", "our". For example, who is the "my" of "My Generation"? |

シフター ポピュラー音楽の歌詞において、「シフター」[10]とは、代名詞として用いられることが多い言葉であり、「誰が、いつ、どこで話しているかによって、参 照先が異なる」[11]ものである。例えば、「私」、「あなた」、「私の」、「私たちの」などである。例えば、「My Generation」の「私の」とは誰のことだろうか? |

| Copyright and royalties See Royalties As of 2021, there are many websites featuring song lyrics. This offering, however, is controversial, since some sites include copyrighted lyrics offered without the holder's permission. The U.S. Music Publishers Association (MPA), which represents sheet music companies, launched a legal campaign against such websites in December 2005. The MPA's president, Lauren Keiser, said the free lyrics web sites are "completely illegal" and wanted some website operators jailed.[12] Lyrics licenses could be obtained worldwide through one of the two aggregators: LyricFind and Musixmatch.[citation needed] The first company to provide licensed lyrics was Yahoo!, quickly followed by MetroLyrics.[citation needed] Several lyric websites are providing licensed lyrics, such as SongMeanings[13] and LyricWiki (defunct as of 2020). Many competing lyrics web sites are still offering unlicensed content, causing challenges around the legality and accuracy of lyrics.[14] In an attempt to crack down unlicensed lyrics web sites, a U.S. federal court has ordered LiveUniverse, a network of websites run by MySpace co-founder Brad Greenspan, to cease operating four sites offering unlicensed song lyrics.[15] |

著作権および使用料 使用料を参照 2021年現在、歌詞を掲載するウェブサイトは数多く存在する。しかし、このサービスは物議を醸している。というのも、一部のサイトでは著作権者の許可な く著作権で保護された歌詞が掲載されているからだ。楽譜会社を代表する米国音楽出版社協会(MPA)は、2005年12月にこのようなウェブサイトに対す る法的キャンペーンを開始した。MPAのローレン・カイザー会長は、歌詞の無料ウェブサイトは「完全に違法」であり、ウェブサイト運営者の一部に実刑判決 を望んでいると述べた。 歌詞のライセンスは、LyricFindとMusixmatchの2つのアグリゲーターのいずれかを通じて世界中で取得できる。[要出典] ライセンス付き歌詞を最初に提供した企業はYahoo!であり、その後すぐにMetroLyricsが続いた。[要出典] ライセンス付き歌詞を提供している歌詞サイトには、SongMeanings[13]やLyricWiki(2020年現在、閉鎖)などがある。 ライセンスのないコンテンツを提供している歌詞ウェブサイトは数多くあり、歌詞の合法性や正確性に関する課題を引き起こしている。[14] ライセンスのない歌詞ウェブサイトを取り締まる試みとして、米国連邦裁判所は、MySpaceの共同創設者であるブラッド・グリーンズパンが運営するウェ ブサイトネットワーク、LiveUniverseに対し、ライセンスのない歌詞を提供する4つのサイトの運営停止を命じた。[15] |

| Academic study Lyrics can be studied from an academic perspective. For example, some lyrics can be considered a form of social commentary. Lyrics often contain political, social, and economic themes—as well as aesthetic elements—and so can communicate culturally significant messages. These messages can be explicit, or implied through metaphor or symbolism. Lyrics can also be analyzed with respect to the sense of unity (or lack of unity) it has with its supporting music. Analysis based on tonality and contrast are particular examples. Former Oxford Professor of Poetry Christopher Ricks famously published Dylan's Visions of Sin, an in-depth and characteristically Ricksian analysis of the lyrics of Bob Dylan; Ricks gives the caveat that to have studied the poetry of the lyrics in tandem with the music would have made for a much more complicated critical feat. |

学術研究 歌 詞は学術的な観点から研究することができる。例えば、いくつかの歌詞は社会的コメントの一形態と考えることができる。歌詞には美的要素だけでなく、政治 的、社会的、経済的なテーマが含まれていることが多く、文化的に重要なメッセージを伝えることができる。これらのメッセージは、明示的な場合もあれば、隠 喩や象徴によって暗示されている場合もある。歌詞は、それを支える音楽との一体感(または一体感の欠如)に関しても分析できる。調性やコントラストに基づ く分析は個別主義的な例である。元オックスフォード大学詩学教授のクリストファー・リックスは、ボブ・ディランの歌詞を徹底的かつ特徴的にリックス流に分 析した『Dylan's Visions of Sin(ディランの罪の幻影)』を出版したことで有名だが、リックスは、歌詞の詩を音楽と並行して研究していたら、もっと複雑な批評的偉業になっていただ ろう、と注意を促している。 |

| Search engines Search risk A 2009 report published by McAfee found that, in terms of potential exposure to malware, lyrics-related searches and searches containing the word "free" are the most likely to have risky results from search engines, both in terms of average risk of all results, and maximum risk of any result.[16] Beginning in late 2014, Google changed its search results pages to include song lyrics. When users search for a name of a song, Google can now display the lyrics directly in the search results page.[17] When users search for a specific song's lyrics, most results show the lyrics directly through a Google search by using Google Play.[18] |

検索エンジン 検索リスク マカフィーが2009年に発表した報告書によると、マルウェアへの潜在的な曝露という観点では、歌詞関連の検索と「無料」という語を含む検索が、検索エン ジンから最もリスクの高い結果が返される可能性が高いことが分かった。これは、すべての結果の平均的なリスクと、いずれかの結果の最大のリスクの両方の観 点からである。[16] 2014年後半より、Googleは検索結果ページに歌詞を含めるように変更した。ユーザーが曲名を検索すると、Googleは検索結果ページに歌詞を直 接表示することができるようになった。[17] ユーザーが特定の曲の歌詞を検索すると、ほとんどの結果はGoogle Playを使用してGoogle検索で歌詞を直接表示する。[18] |

| Lyricist, a writer

of lyrics Libretto, the "little book" of an extended musical piece, written by a librettist "Singing in the Spirit", vocal improvisation in a spiritual context Scat singing & Vocalese, vocal improvisation in jazz bol, kouji, beatbox, forms of vocal mimicry or percussion |

作詞家、歌詞の作者 リブレット、リブレット作家によって書かれた、より長い音楽作品の「小冊子」 「スピリットに歌う」、 スピリチュアルの文脈におけるヴォーカル・インプロヴィゼーション スキャット・シング&ヴォーカリゼ、ジャズにおけるヴォーカル・イ ンプロヴィゼーション ボル、コウジ、ビートボックス、 ヴォーカルの模倣や打楽器のフォーム |

| Moore, Allan F. (2003). Analyzing Popular Music.

Cambridge University Press. Christopher Ricks, (2003). Dylan's Visions of Sin.Viking , 2003 |

|

Christopher Ricks, (2003).

Dylan's Visions of Sin. New York: Ecco.  Dylan's Visions of Sin is a 2004 book by Christopher Ricks, a British poetry scholar and literary critic, in which he considers the songs of Bob Dylan as works of literature (in 2016 Dylan was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature). Ricks' analysis of Dylan's songs is organized around the Christian theological categories of the seven deadly sins, four virtues, and three graces.[1] Ricks writes: Dylan's is an art in which sins are laid bare (and resisted), virtues are valued (and manifested), and the graces brought home. The seven deadly sins, the four cardinal virtues (harder to remember?), and the three heavenly graces: these make up everybody's world, but Dylan's in particular. Or rather, his worlds, since human dealings of every kind are his for the artistic seizing.[2] Reception Charles McGrath, writing about the book in The New York Times, described the book as "a close analysis, line by line sometimes, of the master's greatest hits."[3] McGrath praised Ricks for pointing out connections between Dylan's work and other poets and cultural figures that are "surprising and provocative. At various points he compares Mr. Dylan to Marvell, Marlowe, Keats, Tennyson, Hardy, Yeats and Marlon Brando, to cite just a few of his references."[4] McGrath goes on to suggest that some passages in Dylan's Visions of Sin may strike some readers as over the top, as when Mr. Ricks devotes four pages (and four footnotes) to the lyrics of "All the Tired Horses," a song that is only two lines long—or maybe three, if you count the long "hmmmm" at the end. Other chapters, though, draw insightful and persuasive parallels between, say, "Lay Lady Lay" and John Donne's poem "To His Mistress Going to Bed," between "Not Dark Yet" and Keats's "Ode to a Nightingale," and between "A Hard Rain's A-Gonna Fall" and the Scottish ballad "Lord Randal."[5] Alison Lewis, reviewing the book in Library Journal, hailed Ricks' book as "erudite and incisive ... witty and enjoyable, his analysis broadened by comparisons to the poetry of canonical writers like Eliot, Hopkins, and Larkin." The reviewer notes that "[l]iterally hundreds of books have been written about Bob Dylan and his music, but very few have considered his lyrics as works of literature."[6] https://x.gd/GMCeM |

リックス、クリストファー(2003)『ディランの罪のヴィジョン』

New York: Ecco.  『ディランの罪のヴィジョン』は、英国の詩学者であり文芸評論家であるクリストファー・リックスによる2004年の著書で、ボブ・ディランの歌を文学作品 として考察している(2016年にディランはノーベル文学賞を受賞した)。 リックスによるディランの歌の分析は、キリスト教神学の7つの大罪、4つの美徳、3つの恩寵というカテゴリーを中心に展開されている。[1] リックスは次のように書いている。 ディランの芸術は、罪をあぶり出し(そして抵抗し)、美徳を評価し(そして明示し)、恩寵を実感させるものだ。 7つの大罪、4つの枢要な美徳(覚えにくい?)、そして3つの天上の恩寵:これらは誰もが知る世界を構成しているが、とりわけディランの芸術がそうであ る。 いや、むしろ、あらゆる人間関係を芸術的に表現しているディランの芸術がそうである。 批評 ニューヨーク・タイムズ紙でこの本について書いたチャールズ・マクグラスは、この本を「巨匠のヒット曲を、時には行ごとに細かく分析したもの」と評した。 [3] マクグラスは、リックスがディランの作品と他の詩人や文化的人物とのつながりを指摘していることを賞賛し、そのつながりは「驚くべきもので、刺激的」だと 述べた。彼はさまざまな場面で、ディラン氏をマーベル、マーロウ、キーツ、テニスン、ハーディ、イェーツ、マーロン・ブランドなどと比較している。これは 彼が言及した人物のほんの一部に過ぎない」[4]と述べている。マクグラスはさらに、 『罪のヴィジョン』のいくつかの箇所は、一部の読者にとっては大げさすぎるかもしれない。例えば、リックス氏が2行(あるいは、最後の長い「うーん」を数 えると3行)の歌詞に4ページ(と4つの脚注)を費やしている「オール・ザ・ティアード・ホース」などだ。しかし、他の章では、例えば「レイ・レディ・レ イ」とジョン・ダン(John Donne)の詩「To His Mistress Going to Bed(寝床に向かう愛人へ)」、「Not Dark Yet(まだ暗くない)」とキーツ(Keats)の「Ode to a Nightingale(ナイチンゲールへの頌歌)」、「A Hard Rain's A-Gonna Fall(激しい雨が降るだろう)」とスコットランドのバラード「Lord Randal(ランドル卿)」との類似性を洞察力に富んだ説得力のある形で比較している。[5] アリソン・ルイスは『ライブラリー・ジャーナル』誌でこの本を評し、リックスの本を「博識で鋭い...ウィットに富み、楽しく、彼の分析はエリオット、ホ プキンズ、ラーキンといった正統派の詩人たちの詩との比較によってさらに広がっている」と称賛した。また、この批評家は「文字通り何百冊もの本がボブ・ ディランと彼の音楽について書かれているが、彼の歌詞を文学作品として考察したものはほとんどない」と指摘している。[6] |

O Come, All Ye Faithful (Adeste Fideles) at Westminster Abbey

Spencer X - Be Somebody (Beatbox Music Video)

Heart

Sutra Beatbox Remix -般若心経ビートボックスRemix- by 赤坂陽月.

++++

リ ンク

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

CC

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆