Social anthropology, しゃかいじんるいがく

解説:池田光穂

社会人類学

Social anthropology, しゃかいじんるいがく

解説:池田光穂

社会(society)という人間集団を研究対象にする人類学的研究領域 を社会人類学とよぶ。社会集団の構成員は人間であり、それらの集団は民族集団を構成するこ とがあり、これらの集団は口頭伝承(follore)をもち、また独自の文化と人間固有の文化的共通性ももつので、社会人類学は、[形容詞抜きの]人類 学、民族学、民 俗学、文化人類学と同義語であるという主張も古くからある。

そのため、実際に、文化人類学の同義語と して、日本では民族学や民俗学が、英国では社会人類学が、フランスでは民族学や社会人類学が、ドイツ・ オーストリアでは民俗学や民族学が、スペインでは民俗学が、そして米国では、民俗学や文化人類学という用語がそれぞれ使われている。

また、文化人類学と社会人類学の違いを、 前者は人間文化の共通性や一般性を主に探求し、後者はいわゆる特定の社会集団に関する民族誌あ るいは民族誌学(ethnography)を記述し比較分析する学問であると区 別する人もいる。

このようにみると、民族学、文化人類学、 民俗学、社会人類学、[形容詞抜きの]人類学は、みんな同じだということになってしまうが、実際には、 それらの用語法に関連づけた理論化がなされたり、先にあげた、それぞれの国の事情や国家の歴史的経緯の影響を受けて、独自の発展を遂げた——つまり多様性 があり、それらの学問名のあいだにコンセンサスは無理としても具体的峻別をつけることができる——という事情があるため、それらをやみくもに統一する必要 はないように思われる。[→プロクルステス的な概念の濫用]

■閑話休題01:文化人類学と社会人類学の相 違を 論述せよ

それぞれ、文化人類学者、社会人類学者と僭称する人たちの頭のなかにある「自分が奉ずる学問パラダイム」をそれぞれ言う。これが類似点、あ

るいは相似点。前者の頭になかには、文化を担う主体が想定されていて、前者が考える「社会」は、その集合というレベルでしか想像力がありません。文化人類

学者が、隣接する心理学者を嫌いながら主体の心的メカニズムに回帰する傾向は否めません。後者は、ドーバー海峡を挟んだデュルケームの社会がもたらす集合

的な観念体系の呪縛から忘れることがありませんので、主体=行為者は、その集合的システムを「反映」した行動をとります。デュルケーム的構

造が、後者の人

たちが考える「社会」そのものです。主体は、その構造を体現するエージェントですので、取り換え可能ですし、取り換え可能な「フィールド的応答」を期待し

ています。後者にとって「文化」は体系的な表象をとらない限り、あるいは主体的差異というノイズがはいると、とても不機嫌になります。後者にとって「文

化」は空疎な概念です。これらの差異は、社会と文化という水と油のような相互交流不能な概念を通して、著しい対比をなします。

■閑話休題02:社会学と社会人類学の違い が、この説明からは見えてきません?

デュルケーム派のフィールドワーカーがドーバー海峡を渡ったというのが、社会人類学の「ウラ」の定義ですよ。

《根拠》「ドーバー海峡を挟ん

だデュルケームの社会がもたらす集合 的な観念体系の呪縛から忘れることがありません」上掲「閑話休題01」)

| Social anthropology

is the study of patterns of behaviour in human societies and cultures.

It is the dominant constituent of anthropology throughout the United

Kingdom and much of Europe,[1] where it is distinguished from cultural

anthropology.[2] In the United States, social anthropology is commonly

subsumed within cultural anthropology or sociocultural anthropology. |

社会人類学は、人間社会や文化における行動パターンを研究する学問だ。英国およびヨーロッパの大部分[1] では、文化人類学とは区別され、人類学の主要な構成要素となっている。米国では、社会人類学は通常、文化人類学または社会文化人類学に包含されている。 |

| Comparison with cultural anthropology The term cultural anthropology is generally applied to ethnographic works that are holistic in spirit, are oriented to the ways in which culture affects individual experience, or aim to provide a rounded view of the knowledge, customs, and institutions of people. Social anthropology is a term applied to ethnographic works that attempt to isolate a particular system of social relations such as those that comprise domestic life, economy, law, politics, or religion, give analytical priority to the organizational bases of social life, and attend to cultural phenomena as somewhat secondary to the main issues of social scientific inquiry.[3] Topics of interest for social anthropologists have included customs, economic and political organization, law and conflict resolution, patterns of consumption and exchange, kinship and family structure, gender relations, childbearing and socialization, religion, while present-day social anthropologists are also concerned with issues of globalism, ethnic violence, gender studies, transnationalism and local experience, and the emerging cultures of cyberspace,[4] and can also help with bringing opponents together when environmental concerns come into conflict with economic developments.[5] British and American anthropologists including Gillian Tett and Karen Ho who studied Wall Street provided an alternative explanation for the 2008 financial crisis to the technical explanations rooted in economic and political theory.[6] Differences among British, French, and American sociocultural anthropologies have diminished with increasing dialogue and borrowing of both theory and methods. Social and cultural anthropologists, and some who integrate the two, are found in most institutes of anthropology. Thus the formal names of institutional units no longer necessarily reflect fully the content of the disciplines these cover. Some, such as the Institute of Social and Cultural Anthropology[7] (Oxford), changed their name to reflect the change in composition; others, such as Social Anthropology at the University of Kent,[8] became simply Anthropology. Most retain the name under which they were founded. Long-term qualitative research, including intensive field studies (emphasizing participant observation methods), has been traditionally encouraged in social anthropology rather than quantitative analysis of surveys, questionnaires and brief field visits typically used by economists, political scientists, and (most) sociologists.[9] |

文化人類学との比較 文化人類学という用語は、一般的に、全体論的な精神に立脚し、文化が個人の経験に与える影響に焦点を当て、あるいは人民の知識、慣習、制度について包括的 な見解を提供することを目的とした民族誌的研究に適用される。社会人類学は、家庭生活、経済、法律、政治、宗教など、特定の社会関係のシステムを取り出 し、社会生活の組織的基盤を分析的に優先し、文化現象は社会科学の研究の主な問題よりもやや二次的なものとして扱う民族誌的研究に適用される用語だ。 社会人類学者が関心を持つテーマとしては、慣習、経済・政治組織、法と紛争解決、消費と交換のパターン、親族関係と家族構造、男女関係、出産と社会化、宗 教などが挙げられる。また、現代の社会人類学者は、グローバリズム、民族暴力、ジェンダー研究、トランスナショナル主義と地域体験、サイバースペースの新 たな文化などの問題にも関心を持っており、環境問題と経済開発が対立する場合、反対派を結びつける役割も果たしている[5]。[4] 環境問題と経済発展が対立した場合、対立する両者の妥協点を見出す手助けもしている。[5]ウォール街を研究したジリアン・テットやカレン・ホーなどのイ ギリスやアメリカの人類学者は、経済理論や政治理論に基づく技術的な説明とは別の、2008年の金融危機に関する別の説明を示した。[6] イギリス、フランス、アメリカの社会文化人類学の違いは、理論や方法論の交流や相互借用が進むにつれて、その違いは少なくなっている。社会人類学者と文化 人類学者、および両者を統合する研究者は、ほとんどの人類学研究所に存在する。したがって、機関の正式名称は、これらの分野の内容を完全に反映しなくなっ た。一部は、構成の変化を反映して名称を変更した(例:オックスフォード大学の社会と文化人類学研究所[7])。他方、ケント大学の社会人類学は、単に 「人類学」と改称した[8]。ほとんどの機関は、設立時の名称をそのまま使用している。 社会人類学では、経済学者、政治学者、および(ほとんどの)社会学者によって一般的に使用される、調査、アンケート、および短期の現地訪問による定量分析よりも、集中的な現地調査(参加観察手法を重視)を含む長期的な定性的研究が伝統的に奨励されてきた[9]。 |

| Comparison and intersection with cognitive anthropology Cognitive anthropology studies how people represent and think about events and objects in the world. It links human thought processes and the physical and ideational aspects of culture.[10] The scopes of these two disciplines intersect in the field of cognitive development. The following part of the section shows the significance of their co-research for understanding the processes that constitute society. According to Sir Edward Tylor: "Culture, or civilization, taken in its broad, ethnographic sense, is that complex whole which includes knowledge, belief, art, morals, law, custom, and any other capabilities and habits acquired by man as a member of society.”[11] The cultural consensus principle is incorporated in the reasoning behind the cultural consonance model[12] and other similar models (see cognitive anthropology) that seek to evaluate the effects of shared cognitive structures on social life and the human condition[13] beginning from the onset of cognitive development. The major part of social and cognitive anthropology concepts (e.g., Cultural consonance, Cultural models, Knowledge structures, Shared knowledge etc.) seem to rely upon broad pervasive, unaware interactions between society members. Research shows that unconscious remembering increases recall efficiency over time[14] and yields greater confidence in that thought.[15] According to the received view in cognitive sciences, cognition begins from birth (and even from prenatal) due to motive forces of shared intentionality: unaware knowledge assimilation. Therefore, mechanisms of unaware interactions at the onset of life, one of the focuses of research in cognitive sciences, have become the central research issue in social and cognitive anthropology. Another intersection of these two disciplines appears in neuroscience research. Behavioral propensities (an exteriorization of Cultural models, Schemata, etc.; see key concepts of cognitive anthropology) are the product of biological and cultural factors that manifest in individual brain development, neural wiring, and neurochemical homeostasis.[16] According to received view in neuroscience, an observed human behavior, in any context, is the last event in a long chain of biological and cultural interactions.[17][18] The brain´s anatomy is subject to neuroplasticity and depends on both, contextual (cultural) and historically dependent (previous experience) mechanisms to shape the neural system.[19] By bridging sociology with anthropology and cognitive science perspectives, we can assess shared cultural knowledge[20] – understand processes underlying unspoken social norms and beliefs, as well as study processes of shaping individual values that together constitute societies. |

認知人類学との比較と共通点 認知人類学は、人々が世界における出来事や物事をどのように表現し、どのように考えるかを研究する学問である。人間の思考過程と、文化の物理的側面および 観念的側面とを結びつける。[10] この 2 つの学問分野は、認知の発達という分野で共通点がある。このセクションの次の部分では、社会を構成するプロセスを理解する上で、この 2 つの学問分野の共同研究の重要性を紹介する。エドワード・タイラー卿は、「文化、あるいは文明とは、その広義のエスノグラフィー的な意味において、知識、 信念、芸術、道徳、法律、慣習、および人間が社会の一員として獲得したその他の能力や習慣を含む複雑な全体である」と述べています。[11] 文化の一致の原理は、認知的構造の共有が社会生活と人間の条件に与える影響を評価しようとする文化的一致モデル[12]や類似のモデル(認知人類学参照) の論理的根拠に組み込まれている。これらのモデルは、認知発達のはじまりからその影響を考察する。社会人類学と認知人類学の概念の大部分(例:文化調和、 文化モデル、知識構造、共有知識など)は、社会成員間の広範で普遍的かつ無意識の相互作用に依存しているように見える。研究によると、無意識の記憶は、時 間の経過とともに想起効率を高め[14]、その考えに対する確信度を高めることが明らかになっている[15]。認知科学の通説によれば、認知は、共有され た意図の動機力、すなわち無意識の知識の同化によって、誕生(さらには出生前)から始まる。そのため、認知科学の研究の焦点の一つである、生命の誕生にお ける無意識の相互作用のメカニズムは、社会人類学および認知人類学の重要な研究課題となっている。 これらの二つの学問のもう一つの交点は、神経科学の研究において現れる。行動傾向(文化的モデル、スキーマなどの外在化;認知人類学の主要概念参照)は、 生物学的要因と文化的要因が個々の脳の発達、神経回路の形成、神経化学的恒常性において現れる産物である[16]。神経科学の通説によると、いかなる文脈 においても観察される人間の行動は、生物学的要因と文化的要因の相互作用の長い連鎖の最終的な結果である。[17][18] 脳の解剖学的構造は神経可塑性の影響を受け、神経系を形成するには、文脈的(文化的)メカニズムと歴史的(過去の経験)メカニズムの両方に依存している [19]。社会学と人類学、認知科学の視点を結びつけることで、共有文化知識[20] を評価し、暗黙の社会規範や信念の根底にあるプロセスを理解するとともに、社会を構成する個々の価値観を形成するプロセスを研究することができる。 |

| Focus and practice This section needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources in this section. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. (June 2020) (Learn how and when to remove this message) Social anthropology is distinguished from subjects such as economics or political science by its holistic range and the attention it gives to the comparative diversity of societies and cultures across the world, and the capacity this gives the discipline to re-examine Euro-American assumptions. It is differentiated from sociology, both in its main methods (based on long-term participant observation and linguistic competence),[21] and in its commitment to the relevance and illumination provided by micro studies. It extends beyond strictly social phenomena to culture, art, individuality, and cognition.[22] Many social anthropologists use quantitative methods, too, particularly those whose research touches on topics such as local economies, demography, human ecology, cognition, or health and illness. |

研究対象とその実践 このセクションには、検証のための追加の引用が必要です。信頼できる出典をこのセクションに追加して、この記事の改善にご協力ください。出典が明記されて いない内容は、削除される場合があります。(2020年6月) (このメッセージの削除方法についてはこちらをご覧ください) 社会人類学は、その総合的な範囲と、世界中の社会や文化の比較多様性に注目している点、そしてそれにより欧米の仮定を再検討する能力がある点で、経済学や 政治学などの分野とは区別される。社会学とは、その主な方法(長期にわたる参加観察と言語能力に基づく)[21]、およびミクロ研究によって得られる関連 性や洞察力へのこだわりという点で区別される。社会人類学は、厳密な社会現象だけでなく、文化、芸術、個性、認知にも及ぶ[22]。多くの社会人類学者 は、特に地域経済、人口統計学、人間生態学、認知、保健、病気などの研究分野に携わる者たちは、定量的手法も用いている。 |

| Specializations Main article: Anthropology § Key topics by field: Socio-cultural anthropology Specializations within social anthropology shift as its objects of study are transformed and as new intellectual paradigms appear; musicology and medical anthropology are examples of current, well-defined specialities.[23] More recent and currently specializations are: cognitive development – neuroscience research for the neuroplasticity and the shared intentionality approach to the extended mind thesis: the anthropological analysis of ecological learning in cognitive development;[24][16] social and ethical understandings of novel technologies – the way anthropologists analyze everyday life, cultural reproduction, and human evolution;[25] kinship – emergent forms of "the family" and other new socialities modelled on kinship;[26] postsocialism crisis – the ongoing social fall-out of the demise of state socialism;[27] the politics of resurgent religiosity;[28] and audit cultures – analysis of audit cultures and accountability.[29] The subject has been enlivened by, and has contributed to, approaches from other disciplines, such as philosophy (ethics, phenomenology, logic), the history of science, psychoanalysis, and linguistics. Ethical considerations The subject has both ethical and reflexive dimensions. Practitioners have developed an awareness of the sense in which scholars create their objects of study and the ways in which anthropologists themselves may contribute to processes of change in the societies they study. An example of this is the "hawthorne effect", whereby those being studied may alter their behaviour in response to the knowledge that they are being watched and studied. |

専門分野 主な記事:人類学 § 分野別の主要トピック:社会文化人類学 社会人類学の専門分野は、その研究対象が変化し、新しい知的パラダイムが出現するにつれて変化している。音楽学や医療人類学は、現在の明確な専門分野の例だ。[23] より最近、そして現在の専門分野は次のとおりだ。 認知発達 – 神経可塑性に関する神経科学の研究、および拡張された心説に対する共有意図アプローチ:認知発達における生態学的学習の人類学的分析[24][16] 新しい技術に関する社会的・倫理的理解 – 人類学者が日常生活、文化の再現、および人間の進化を分析する方法[25] 親族関係 – 親族関係をモデルにした「家族」の新たな形態と他の新しい社会性;[26] ポスト社会主義危機 – 国家社会主義の崩壊に伴う継続的な社会的混乱;[27] 再興する宗教性の政治;[28]および 監査文化 – 監査文化と責任追及の分析。[29] このテーマは、哲学(倫理学、現象学、論理学)、科学史、精神分析学、言語学など、他の学問分野からのアプローチによって活性化され、またそれらに貢献してきた。 倫理的考慮 このテーマには、倫理的次元と反射的次元がある。研究者は、研究対象をどのように創造するか、そして人類学者が研究対象とする社会の変化プロセスにどのよ うに貢献する可能性があるかについて、意識を高めてきた。その一例が「ホーソン効果」で、研究対象者が観察され研究されていることを知ると、その行動が変 化する可能性がある。 |

| History Main article: History of anthropology Social anthropology has historical roots in a number of 19th-century disciplines, including the study of Classics, ethnography, ethnology, folklore, linguistics, and sociology, among others. Its immediate precursor took shape in the work of Edward Burnett Tylor and James George Frazer in the late 19th century and underwent major changes in both method and theory during the period 1890–1920 with a new emphasis on original fieldwork, long-term holistic study of social behavior in natural settings, and the introduction of French and German social theory. Polish anthropologist and ethnographer Bronisław Malinowski, one of the most important influences on British social anthropology, emphasized long-term fieldwork in which anthropologists work in the vernacular and immerse themselves in the daily practices of local people.[30] This development was bolstered by Franz Boas' introduction of the concept of cultural relativism, arguing that cultures are based on different ideas about the world and can therefore only be properly understood in terms of their own standards and values.[31]  The British Museum, London Museums such as the British Museum weren't the only site of anthropological studies; with the New Imperialism period, starting in the 1870s, zoos became unattended "laboratories", especially the so-called "ethnological exhibitions" or "Negro villages". Thus, "savages" from the Americas, Africa and Asia were displayed, often nude, in cages, in what has been termed "human zoos". In 1906, Congolese pygmy Ota Benga was put by American anthropologist Madison Grant in a cage in the Bronx Zoo, labelled "the missing link" between an orangutan and the "White race"—Grant, a renowned eugenicist, was also the author of The Passing of the Great Race (1916). Such exhibitions were attempts to illustrate and prove in the same movement the validity of scientific racism, whose first formulation may be found in Arthur de Gobineau's An Essay on the Inequality of Human Races (1853–1855). In 1931, the Colonial Exhibition in Paris still displayed Kanaks from New Caledonia in the "indigenous village"; it received 24 million visitors in six months, thus demonstrating the popularity of such "human zoos". Anthropology grew increasingly distinct from natural history and by the end of the 19th century the discipline began to crystallize into its modern form—by 1935, for example, it was possible for T. K. Penniman to write a history of the discipline entitled A Hundred Years of Anthropology. At the time, the field was dominated by "the comparative method". It was assumed that all societies passed through a single evolutionary process from the most primitive to most advanced. Non-European societies were thus seen as evolutionary "living fossils" that could be studied in order to understand the European past. Scholars wrote histories of prehistoric migrations which were sometimes valuable but often also fanciful. It was during this time that Europeans first accurately traced Polynesian migrations across the Pacific Ocean for instance—although some of them believed it originated in Egypt. Finally, the concept of race was actively discussed as a way to classify—and rank—human beings based on difference. |

歴史 主な記事:人類学の歴史 社会人類学は、古典学、民族誌、民族学、民俗学、言語学、社会学など、19 世紀のさまざまな学問分野に歴史的なルーツがある。その直接の先駆者は、19 世紀後半のエドワード・バーネット・タイラーとジェームズ・ジョージ・フレイザーの研究で形になり、1890 年から 1920 年にかけて、独自のフィールドワーク、自然環境における社会行動の長期的な総合的研究、フランスやドイツの社会理論の導入が重視されるようになり、方法と 理論の両面で大きな変化を遂げた。 英国の社会人類学に最も大きな影響を与えた人物の一人であるポーランドの人類学者・エスノグラファー、ブロニスワフ・マリノフスキーは、人類学者が現地の 言語を使い、現地の人々の日常生活に没頭する長期のフィールドワークを重要視した。[30] この動きは、文化は世界に関する異なる考えに基づいており、したがって、その文化独自の基準や価値観によってのみ正しく理解することができると主張した、 フランツ・ボアズによる文化相対主義の概念の導入によって後押しされた。  大英博物館、ロンドン 人類学の研究場は、大英博物館だけではありませんでした。1870年代から始まった新帝国主義時代、動物園は、特に「民族学展示」や「ニグロ村」と呼ばれ る、無人の「実験室」となりました。こうして、アメリカ大陸、アフリカ、アジアからの「野蛮人」たちが、多くの場合裸で、檻の中に「人間動物園」とでも言 うべき状態で展示されました。1906年、コンゴのピグミー、オタ・ベンガは、アメリカの人類学者マディソン・グラントによって、ブロンクス動物園の檻に 入れられ、「オランウータンと「白人種」の間の「失われたリンク」とラベルが貼られた。グラントは、有名な優生学者であり、『偉大なる人種の滅亡』 (1916年)の著者でもある。このような展示は、科学的人種主義の妥当性を一挙に説明し、証明する試みだった。科学的人種主義は、アルチュール・ド・ゴ ビノーの『人種の不平等に関するエッセイ』(1853-1855)で初めて提唱された。1931年のパリ植民地博覧会では、ニューカレドニアのカナック族 が「先住民の村」に展示され、6ヶ月間で2400万人の来場者を集め、このような「人間動物園」の人気を証明した。 人類学は自然史から次第に独立し、19世紀末までに現代の形態へと結晶化していった。例えば1935年には、T. K. ペンニマンが『人類学の100年』と題した学問史を執筆することが可能になった。当時、この分野は「比較方法」が主流だった。すべての社会は、最も原始的 な段階から最も進んだ段階へと単一の進化過程を経ると考えられていた。非ヨーロッパ社会は、ヨーロッパの過去を理解するための研究対象として、進化の「生 きた化石」と見なされていた。学者たちは、先史時代の移住の歴史を執筆したが、その内容は貴重なものではあったものの、多くの場合は空想に満ちたもので あった。例えば、ヨーロッパ人が太平洋を横断したポリネシア人の移住を初めて正確に追跡したのはこの時代のことだが、その一部はエジプトが移住の起源であ ると信じていた。最後に、人種という概念は、人間をその違いに基づいて分類し、ランク付けする方法として活発に議論された。 |

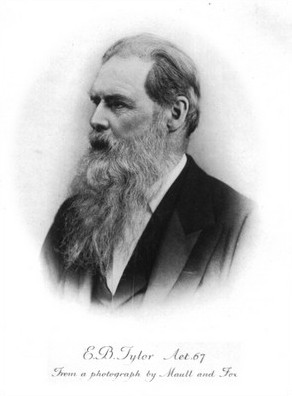

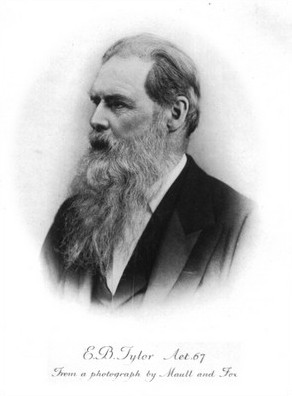

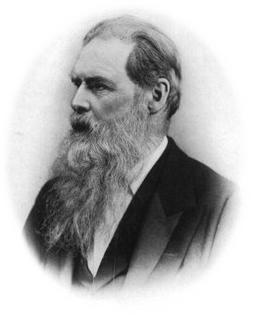

Tylor and Frazer Edward Burnett Tylor, 19th-century British anthropologist Edward Burnett Tylor (1832–1917) and James George Frazer (1854–1941) are generally considered the antecedents to modern social anthropologists in Great Britain. Although the British anthropologist Tylor undertook a field trip to Mexico, both he and Frazer derived most of the material for their comparative studies through extensive reading, not fieldwork, mainly the Classics (literature and history of Ancient Greece and Rome), the work of the early European folklorists, and reports from missionaries, travelers, and contemporaneous ethnologists. Tylor advocated strongly for unilinealism and a form of "uniformity of mankind".[32] Tylor in particular laid the groundwork for theories of cultural diffusionism, stating that there are three ways that different groups can have similar cultural forms or technologies: "independent invention, inheritance from ancestors in a distant region, transmission from one race [sic] to another."[33] Tylor formulated one of the early and influential anthropological conceptions of culture as "that complex whole, which includes knowledge, belief, art, morals, law, custom, and any other capabilities and habits acquired by [humans] as [members] of society."[34] However, as Stocking notes, Tylor mainly concerned himself with describing and mapping the distribution of particular elements of culture, rather than with the larger function, and he generally seemed to assume a Victorian idea of progress rather than the idea of non-directional, multilineal cultural change proposed by later anthropologists. Tylor also theorized about the origins of religious beliefs in human beings, proposing a theory of animism as the earliest stage, and noting that "religion" has many components, of which he believed the most important to be belief in supernatural beings (as opposed to moral systems, cosmology, etc.). Frazer, a Scottish scholar with a broad knowledge of Classics, also concerned himself with the study of religion, mythology, and magic. His comparative studies, most influentially in the numerous editions of The Golden Bough, analyzed similarities in religious belief and symbolism globally. Neither Tylor nor Frazer, however, were particularly interested in fieldwork, nor were they interested in examining how the cultural elements and institutions fit together. The Golden Bough was abridged drastically in subsequent editions after his first. |

タイラーとフレイザー エドワード・バーネット・タイラー、19 世紀のイギリス人人類学者 エドワード・バーネット・タイラー(1832–1917)とジェームズ・ジョージ・フレイザー(1854–1941)は、一般的にイギリスにおける現代社 会人類学の先駆者と見なされています。イギリスの人類学者タイラーはメキシコへの現地調査を行ったが、彼とフレイザーは比較研究の材料のほとんどを、現地 調査ではなく、主に古典(古代ギリシャとローマの文学と歴史)、初期のヨーロッパの民俗学者の著作、宣教師、旅行者、同時代の民族学者の報告書の広範な読 書から得た。 タイラーは、一系主義と「人類の均一性」を強く主張した[32]。特にタイラーは、異なる集団が類似の文化形態や技術を持つには 3 つの方法がある、と述べて、文化拡散説の基礎を築いた。「独立発明、遠方の先祖からの継承、ある人種から別の人種への伝播」[33]。 タイラーは、文化を「知識、信仰、芸術、道徳、法律、習慣、および社会の一員として人間が獲得したその他の能力や習慣を含む複雑な全体」と定義する、人類 学における初期の重要な概念の一つを提唱した。[34] しかし、ストッキングが指摘するように、タイラーは文化のより大きな機能よりも、文化の特定の要素の分布を記述し、地図上に表すことに主に関心があり、後 の人類学者たちが提唱した、方向性のない多線的な文化の変化という考え方よりも、ビクトリア時代の進歩の考え方を一般的に前提としていたようです。タイ ラーはまた、人間の宗教的信念の起源について理論化し、その最初期段階としてアニミズムの理論を提唱し、「宗教」には多くの要素があるものの、その最も重 要な要素は(道徳体系や宇宙論などとは対照的に)超自然的な存在の信念であると指摘した。 古典に幅広い知識を持つスコットランドの学者であるフレイザーも、宗教、神話、呪術の研究に従事していた。彼の比較研究は、数多くの版が発行された『黄金 の枝』で最も影響力があり、世界各国の宗教的信念や象徴の類似点を分析したものだった。しかし、タイラーもフレザーも、フィールドワークにはあまり関心が なく、文化的な要素や制度がどのように組み合わされているかを考察することにも興味がなかった。『黄金の枝』は、初版以降、後続の版で大幅に要約された。 |

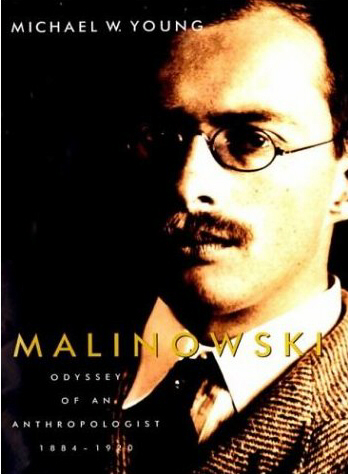

Malinowski and the British School Bronisław Malinowski, Polish anthropologist and ethnographer at the London School of Economics and Political Science Toward the turn of the 20th century, a number of anthropologists became dissatisfied with this categorization of cultural elements; historical reconstructions also came to seem increasingly speculative to them. Under the influence of several younger scholars, a new approach came to predominate among British anthropologists, concerned with analyzing how societies held together in the present (synchronic analysis, rather than diachronic or historical analysis), and emphasizing long-term (one to several years) immersion fieldwork. Cambridge University financed a multidisciplinary expedition to the Torres Strait Islands in 1898, organized by Alfred Cort Haddon and including a physician-anthropologist, William Rivers, as well as a linguist, a botanist, and other specialists. The findings of the expedition set new standards for ethnographic description. A decade and a half later, the Polish anthropology student Bronisław Malinowski (1884–1942) was beginning what he expected to be a brief period of fieldwork in the old model, collecting lists of cultural items, when the outbreak of the First World War stranded him in New Guinea. As a subject of the Austro-Hungarian Empire resident on a British colonial possession, he was effectively confined to New Guinea for several years.[35] He made use of the time by undertaking far more intensive fieldwork than had been done by British anthropologists, and his classic ethnographical work, Argonauts of the Western Pacific (1922) advocated an approach to fieldwork that became standard in the field: getting "the native's point of view" through participant observation. Theoretically, he advocated a functionalist interpretation, which examined how social institutions functioned to satisfy individual needs. |

マリノフスキーと英国学派 ブロニスワフ・マリノフスキー、ポーランドの人類学者、ロンドン・スクール・オブ・エコノミクス・アンド・ポリティカル・サイエンスのエスノグラファー 20 世紀の変わり目に、多くの人類学者が文化要素のこの分類に不満を抱き始め、歴史的再構築もますます推測の域を出ないものになっていきました。若手の研究者 たちの影響を受けて、イギリス人類学者の間で新たなアプローチが主流となった。このアプローチは、社会が現在どのように機能しているかを分析する(同期的 分析、歴史的分析や時代的分析ではなく)ことに焦点を当て、長期(1年から数年間)の現地調査を重視するものだった。1898年、ケンブリッジ大学は、ア ルフレッド・コート・ハドソンが企画した、医師であり人類学者でもあるウィリアム・リバーズ、言語学者、植物学者、その他の専門家からなる学際的な探検隊 を、トレス海峡諸島に派遣した。この探検隊の成果は、民族誌的記述の新しい基準を打ち立てた。 15年後、ポーランドの人類学学生ブロニスラフ・マリノフスキー(1884–1942)は、旧来のモデルに基づく短期のフィールドワークを開始し、文化遺 産のリストを収集していたが、第一次世界大戦の勃発によりニューギニアに足止めされた。オーストリア=ハンガリー帝国の臣民としてイギリス植民地に居住し ていたため、彼は数年間ニューギニアに拘束された。[35] 彼はこの時間を、英国の民族学者たちよりもはるかに集中的なフィールドワークに費やした。そして、彼の古典的な民族誌『西太平洋のアルゴナウタイ』 (1922年)は、参加観察を通じて「先住民の視点」を得るという、この分野における標準的なフィールドワークの手法を提唱した。理論的には、彼は、社会 制度が個人のニーズをどのように満たしているかを考察する機能主義的解釈を提唱した。 |

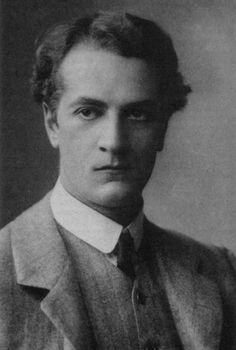

1920s–1940 Main entrance to the London School of Economics and Political Science Modern social anthropology was founded in Britain at the London School of Economics and Political Science following World War I. Influences include both the methodological revolution pioneered by Bronisław Malinowski's process-oriented fieldwork in the Trobriand Islands of Melanesia between 1915 and 1918[36] and Alfred Radcliffe-Brown's theoretical program for systematic comparison that was based on a conception of rigorous fieldwork and the structure-functionalist conception of Durkheim’s sociology.[37][38] Other intellectual founders include W. H. R. Rivers and A. C. Haddon, whose orientation reflected the contemporary Parapsychologies of Wilhelm Wundt and Adolf Bastian, and Sir E. B. Tylor, who defined anthropology as a positivist science following Auguste Comte. Edmund Leach (1962) defined social anthropology as a kind of comparative micro-sociology based on intensive fieldwork studies. Scholars have not settled a theoretical orthodoxy on the nature of science and society, and their tensions reflect views which are seriously opposed.  A. R. Radcliffe-Brown A. R. Radcliffe-Brown also published a seminal work in 1922. He had carried out his initial fieldwork in the Andaman Islands in the old style of historical reconstruction. However, after reading the work of French sociologists Émile Durkheim and Marcel Mauss, Radcliffe-Brown published an account of his research (entitled simply The Andaman Islanders) that paid close attention to the meaning and purpose of rituals and myths. Over time, he developed an approach known as structural functionalism, which focused on how institutions in societies worked to balance out or create an equilibrium in the social system to keep it functioning harmoniously. His structuralist approach contrasted with Malinowski's functionalism, and was quite different from the later French structuralism, which examined the conceptual structures in language and symbolism. Malinowski and Radcliffe-Brown's influence stemmed from the fact that they, like Boas, actively trained students and aggressively built up institutions that furthered their programmatic ambitions. This was particularly the case with Radcliffe-Brown, who spread his agenda for "Social Anthropology" by teaching at universities across the British Empire and Commonwealth. From the late 1930s until the postwar period appeared a string of monographs and edited volumes that cemented the paradigm of British Social Anthropology (BSA). Famous ethnographies include The Nuer, by Edward Evan Evans-Pritchard, and The Dynamics of Clanship Among the Tallensi, by Meyer Fortes; well-known edited volumes include African Systems of Kinship and Marriage and African Political Systems. |

1920年代~1940年代 ロンドン・スクール・オブ・エコノミクス・アンド・ポリティカル・サイエンスの正面入口 現代社会人類学は、第一次世界大戦後にイギリスのロンドン・スクール・オブ・エコノミクス・アンド・ポリティカル・サイエンスで創設された。その影響に は、1915年から1918年にかけてメラネシアのトロブリアンド諸島で行われたブロニスワフ・マリノフスキーのプロセス指向のフィールドワークによる方 法論的革命[36]と、アルフレッド・ラドクリフ=ブラウンによる、厳格なフィールドワークとデュルケームの社会学の構造機能主義的概念に基づく体系的な 比較のための理論的プログラムが含まれる。[37][38] その他の知的創始者としては、W. H. R. リバースと A. C. ハドンが挙げられ、彼らの方向性は、ヴィルヘルム・ヴントとアドルフ・バスティアンによる当時の超心理学を反映したものだった。また、オーギュスト・コン トに倣って人類学を実証主義的な科学と定義した E. B. タイラーも、その一人である。エドモンド・リーチ(1962)は、社会人類学を、集中的なフィールドワーク研究に基づく一種の比較ミクロ社会学と定義し た。学者たちは、科学と社会の性質に関する理論的な正統性を確立しておらず、その対立は、激しく対立する見解を反映している。  A. R. ラドクリフ・ブラウン A. R. ラドクリフ=ブラウンも1922年に画期的な著作を発表した。彼は当初、アンダマン諸島で歴史的再構築の伝統的な手法によるフィールドワークを実施した。 しかし、フランスの社会学者エミール・デュルケームとマルセル・モースの著作を読んだ後、彼は研究報告(『アンダマン諸島の住民』と題された)を発表し、 儀式や神話の意義と目的に注目した。その後、彼は、社会における制度が、社会システムの調和を保ち、その機能を維持するために、どのようにバランスを取 り、均衡を構築しているかに焦点を当てた「構造機能主義」というアプローチを開発した。彼の構造主義的アプローチは、マリノフスキーの機能主義とは対照的 であり、言語や象徴の概念構造を考察した後のフランスの構造主義とはまったく異なるものだった。 マリノフスキーとラドクリフ・ブラウンの影響力は、ボアズと同様、学生を積極的に指導し、自らのプログラム的野望を推進する機関を精力的に設立したことに 由来する。特にラドクリフ・ブラウンは、大英帝国および英連邦の大学で教鞭を執り、「社会人類学」の理念を広めた。1930年代後半から戦後にかけて、英 国社会人類学(BSA)のパラダイムを固める一連の単行本や編集書が相次いで出版された。有名な民族誌としては、エドワード・エヴァン・エヴァンス・プ リッチャードの『ヌエル族』やマイヤー・フォーテスの『タレンシ族の氏族の力学』があり、有名な編集書としては『アフリカの親族制度と結婚制度』や『アフ リカの政治制度』がある。 |

| Post-World War II trends Further information: Aftermath of World War II Following World War II, sociocultural anthropology as comprised by the fields of ethnography and ethnology diverged into an American school of cultural anthropology while social anthropology diversified in Europe by challenging the principles of structure-functionalism, absorbing ideas from Claude Lévi-Strauss's structuralism and from the followers of Max Gluckman, and embracing the study of conflict, change, urban anthropology, and networks. Together with many of his colleagues at the Rhodes-Livingstone Institute and students at Manchester University, collectively known as the Manchester School, took BSA in new directions through their introduction of explicitly Marxist-informed theory, their emphasis on conflicts and conflict resolution, and their attention to the ways in which individuals negotiate and make use of the social structural possibilities. During this period Gluckman was also involved in a dispute with American anthropologist Paul Bohannan on ethnographic methodology within the anthropological study of law. He believed that indigenous terms used in ethnographic data should be translated into Anglo-American legal terms for the benefit of the reader.[39][40] The Association of Social Anthropologists of the UK and Commonwealth was founded in 1946.[41] In Britain, anthropology had a great intellectual impact, it "contributed to the erosion of Christianity, the growth of cultural relativism, an awareness of the survival of the primitive in modern life, and the replacement of diachronic modes of analysis with synchronic, all of which are central to modern culture."[42] Later in the 1960s and 1970s, Edmund Leach and his students Mary Douglas and Nur Yalman, among others, introduced French structuralism in the style of Claude Lévi-Strauss. In countries of the British Commonwealth, social anthropology has often been institutionally separate from physical anthropology and primatology, which may be connected with departments of biology and zoology; and from archaeology, which may be connected with departments of Classics, Egyptology, Oriental studies, and the like. In other countries (and in some, particularly smaller, British and North American universities), anthropologists have also found themselves institutionally linked with scholars of cultural studies, ethnic studies, folklore, human geography, museum studies, sociology, social relations, and social work. British anthropology has continued to emphasize social organization and economics over purely symbolic or literary topics. |

第二次世界大戦後の動向 詳細情報:第二次世界大戦後 第二次世界大戦後、民族誌学と民族学から構成される社会文化人類学は、アメリカでは文化人類学という学派に分かれ、ヨーロッパでは構造機能主義の原則に異 議を唱え、クロード・レヴィ=ストロースの構造主義やマックス・グルックマンの弟子たちの思想を取り入れ、紛争、変化、都市人類学、ネットワークの研究を 取り入れるなど、多様化が進んだ。マンチェスター大学でローデス・リビングストン研究所の同僚や学生たちと共働し、マンチェスター学派として知られるグ ループは、明確にマルクス主義に影響を受けた理論の導入、紛争と紛争解決への強調、個人が社会的構造の可能性を交渉し活用する方法への注目を通じて、 BSAに新たな方向性を示した。この期間、グルックマンは、人類学における法学の研究における民族誌的手法について、アメリカの人類学者ポール・ボハンナ ンと論争を繰り広げた。彼は、民族誌的データで使用される先住民の言葉は、読者の理解のために英米の法律用語に翻訳すべきだと考えていた[39] [40]。1946年に、英国および英連邦社会人類学者協会が設立された[41]。 イギリスでは、人類学は大きな知的影響を与え、「キリスト教の衰退、文化相対主義の台頭、現代社会における原始的な要素の存続への認識、そして歴史的分析 方法から同時的分析方法への移行など、現代文化の核心をなす諸現象に貢献した」とされている。[42] 1960年代後半から1970年代にかけて、エドムンド・リーチとその弟子であるメアリー・ダグラスやヌール・ヤルマンらは、クロード・レヴィ=ストロー スのスタイルを継承したフランス構造主義をイギリスに導入した。 英連邦諸国では、社会人類学は、生物学や動物学の学科と関連のある自然人類学や霊長類学、および古典学、エジプト学、東洋学などの学科と関連のある考古学 とは、制度上、しばしば分離されている。他の国々(特に小規模な英国や北米の大学)では、人類学者は文化研究、民族学、民俗学、人間地理学、博物館学、社 会学、社会関係、社会福祉学などの学者たちと組織的に連携している。英国の人類学は、純粋に象徴的または文学的なトピックよりも、社会組織や経済を重要視 し続けています。 |

| 1980s to present The European Association of Social Anthropologists (EASA) was founded in 1989 as a society of scholarship at a meeting of founder members from fourteen European countries, supported by the Wenner-Gren Foundation for Anthropological Research. The Association seeks to advance anthropology in Europe by organizing biennial conferences and by editing its academic journal, Social Anthropology/Anthropologies Social. Departments of Social Anthropology at different universities have tended to focus on disparate aspects of the field, and can be found in several universities around the world. The field of social anthropology has expanded in ways not anticipated by the founders of the field, as for example in the subfield of structure and dynamics. |

1980年代から現在 欧州社会人類学会(EASA)は、1989年に、14カ国の創設メンバーによる会議で、ウェナー・グレン人類学研究財団の支援を受けて、学術団体として設 立された。この協会は、2年に1度の会議の開催や、学術誌『Social Anthropology/Anthropologies Social』の編集を通じて、ヨーロッパにおける人類学の進歩を目指している。異なる大学の社会人類学部門は、この分野におけるさまざまな側面に焦点を 当てている傾向があり、世界中のいくつかの大学に見られる。社会人類学の分野は、構造とダイナミクスなどのサブ分野において、この分野の創設者が予想しな かった形で拡大している。 |

| Anthropologists associated with social anthropology Andre Beteille[43] Aleksandar Boskovic Edmund Snow Carpenter Philippe Descola Mary Douglas[44] Thomas Hylland Eriksen E. E. Evans-Pritchard Raymond Firth Rosemary Firth[45] Meyer Fortes Ernest Gellner Stephen D. Glazier Jack Goody David Graeber Don Kalb Adam Kuper Edmund Leach Murray Leaf Claude Lévi-Strauss David MacDougall Judith MacDougall Alan Macfarlane[46] Bronisław Malinowski Siegfried Frederick Nadel A.H.J. Prins Alfred Radcliffe-Brown Juan Mauricio Renold Audrey Richards Victor Turner Marshall Sahlins Marilyn Strathern Hebe Vessuri Susan Visvanathan Douglas R. White Eric Wolf Robert Layton |

社会人類学に関連する人類学者 アンドレ・ベテイル[43 アレクサンダー・ボスコヴィッチ エドモンド・スノー・カーペンター フィリップ・デスコラ メアリー・ダグラス[44 トーマス・ヒランド・エリクセン E. E. エヴァンス・プリッチャード レイモンド・ファース ローズマリー・ファース[45 マイヤー・フォルテス アーネスト・ゲルナー スティーブン・D・グラジエ ジャック・グッディ デヴィッド・グレイバー ドン・カルブ アダム・クーパー エドモンド・リーチ マレー・リーフ クロード・レヴィ=ストロース デビッド・マクドゥガル ジュディス・マクドゥガル アラン・マクファーレン[46] ブロニスワフ・マリノフスキー ジークフリート・フレデリック・ナデル A.H.J. プリンス アルフレッド・ラドクリフ・ブラウン フアン・マウリシオ・レノルド オードリー・リチャーズ ヴィクター・ターナー マーシャル・サールズ マリリン・ストラターン ヘベ・ヴェッサーリ スーザン・ヴィスヴァナタン ダグラス・R・ホワイト エリック・ウルフ ロバート・レイトン |

| Cultural anthropology Ethnology Ethnosemiotics List of important publications in anthropology Rajamandala |

文化人類学 民族学 民族記号学 人類学における重要な出版物のリスト ラジャマンダラ |

| Further reading Malinowski, Bronislaw (1915): The Trobriand Islands Malinowski, Bronislaw (1922): Argonauts of the Western Pacific Malinowski, Bronislaw (1929): The Sexual Life of Savages in North-Western Melanesia Malinowski, Bronislaw (1935): Coral Gardens and Their Magic: A Study of the Methods of Tilling the Soil and of Agricultural Rites in the Trobriand Islands Leach, Edmund (1954): Political systems of Highland Burma. London: G. Bell. Leach, Edmund (1982): Social Anthropology Eriksen, Thomas H. (1985):, pp. 926–929 in The Social Science Encyclopedia Kuper, Adam; Kuper, Jessica (January 1985). Social Anthropology. Routledge & Kegan Paul. ISBN 0-7102-0008-0. OCLC 11623683. Kuper, Adam (1996): Anthropology and Anthropologists: The Modern British School. ISBN 0-415-11895-6. OCLC 32509209. |

さらに読む マリノフスキー、ブロニスラフ(1915):『トロブリアンド諸島 マリノフスキー、ブロニスラフ(1922):『西太平洋の遠洋航海者 マリノフスキー、ブロニスラフ(1929):『北西メラネシアの野蛮人の性生活 マリノフスキー、ブロニスワフ(1935):『サンゴの庭とその呪術:トロブリアンド諸島の土壌耕作法と農業儀式に関する研究 リーチ、エドモンド(1954):『ビルマ高地の政治体制』。ロンドン:G. ベル。 リーチ、エドモンド(1982):『社会人類学 エリクセン、トーマス H. (1985):, pp. 926–929 in 社会科学百科事典 クーパー、アダム; クーパー、ジェシカ (1985年1月). 社会人類学. Routledge & Kegan Paul. ISBN 0-7102-0008-0. OCLC 11623683. クーパー、アダム(1996):『人類学と人類学者:現代の英国学派』。ISBN 0-415-11895-6。OCLC 32509209。 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Social_anthropology |

文献

リンク

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

From Left:

Edward Burnett Tylor(1832-1917), Bronislaw Kasper

Malinowski(1884-1942), Alfred Reginald Radcliffe-Brown(1881-1955), Mary

Douglas(1921-2007), Edward Evan Evans-Pritchard(1902-1973), Edmund

Ronald Leach(1910-1989)

It is with the lawyers that the problem of the modern state originates as an actual theory; for the lawyer's fomulae have been rather amplified than denied by the philosophers - Harold Laski, The Pluralistic State.1921.

++

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆