エクアドルの先住民

Indigenous peoples in Ecuador

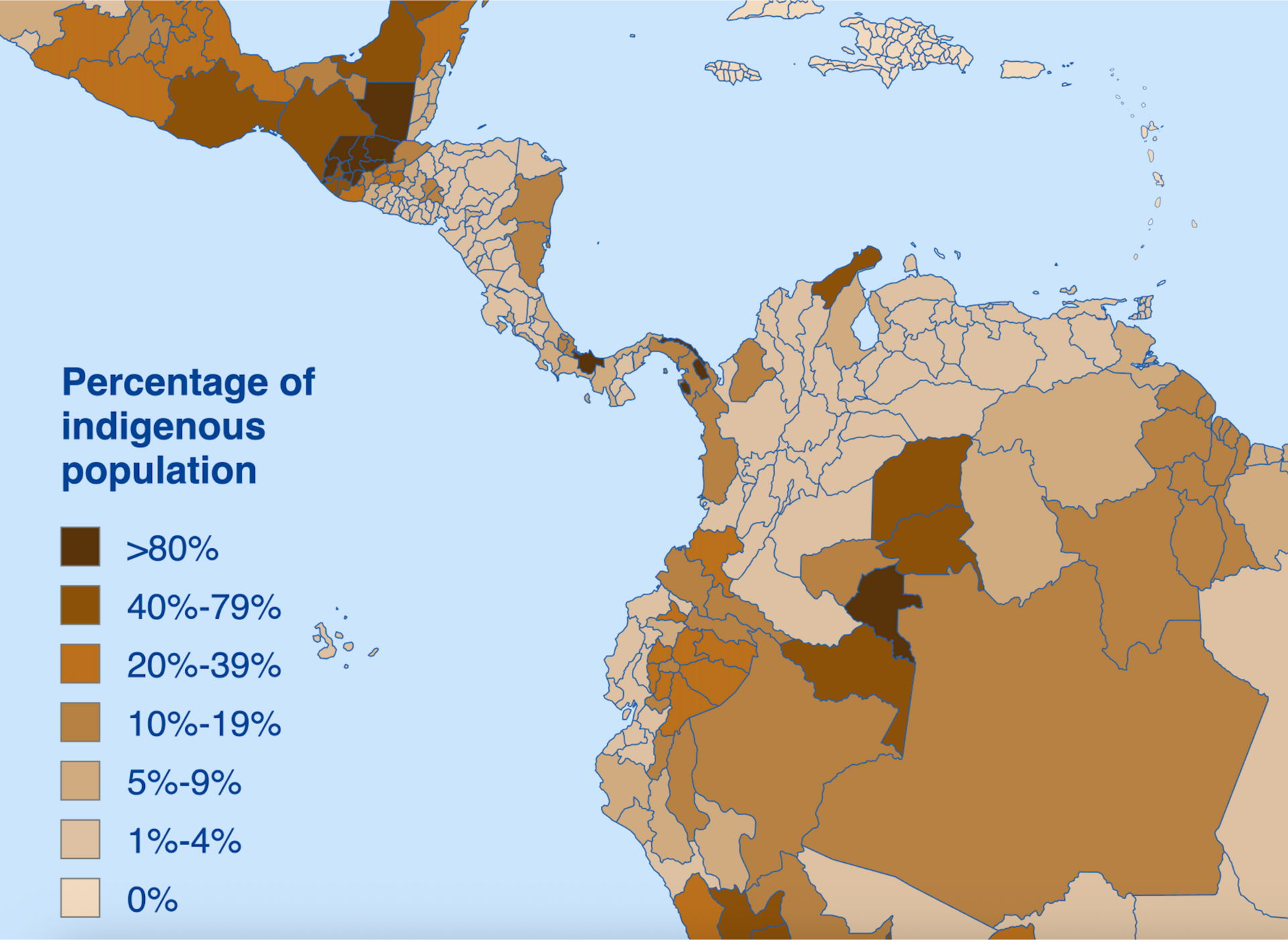

Percentage of indigenous population of the Northern South America/ Bartolo Ushigua, Zapara delegate at the 2nd CONAIE congress[→コナイエ]

☆エクアドルの先住民、またはエクアドル先住民(Indigenous peoples in Ecuador or Native Ecuadorians; スペイン語: Ecuatorianos Nativos)は、スペインによるアメリカ大陸植民地化以前にエクアドルに存在した人々のグループである(2022年のセンサスでは先住民人口 130万人)。この言葉には、スペインによる征服時代から現 在に至るまでの子孫も含まれる。エクアドルの人口の8パーセントが先住民族であり、残りの70パーセントは先住民族とヨーロッパ人の混血であるメスティー ソである[3]。先住民人口が高い地域は、アンデス高地および東部地域で、人口順に、ピチンチャ県(19万人)、チンボラソ県(17万人)、インバブア(13万人)、モロナ・サンティアゴ県(11万人)、コトパクシ県(11万人)である。

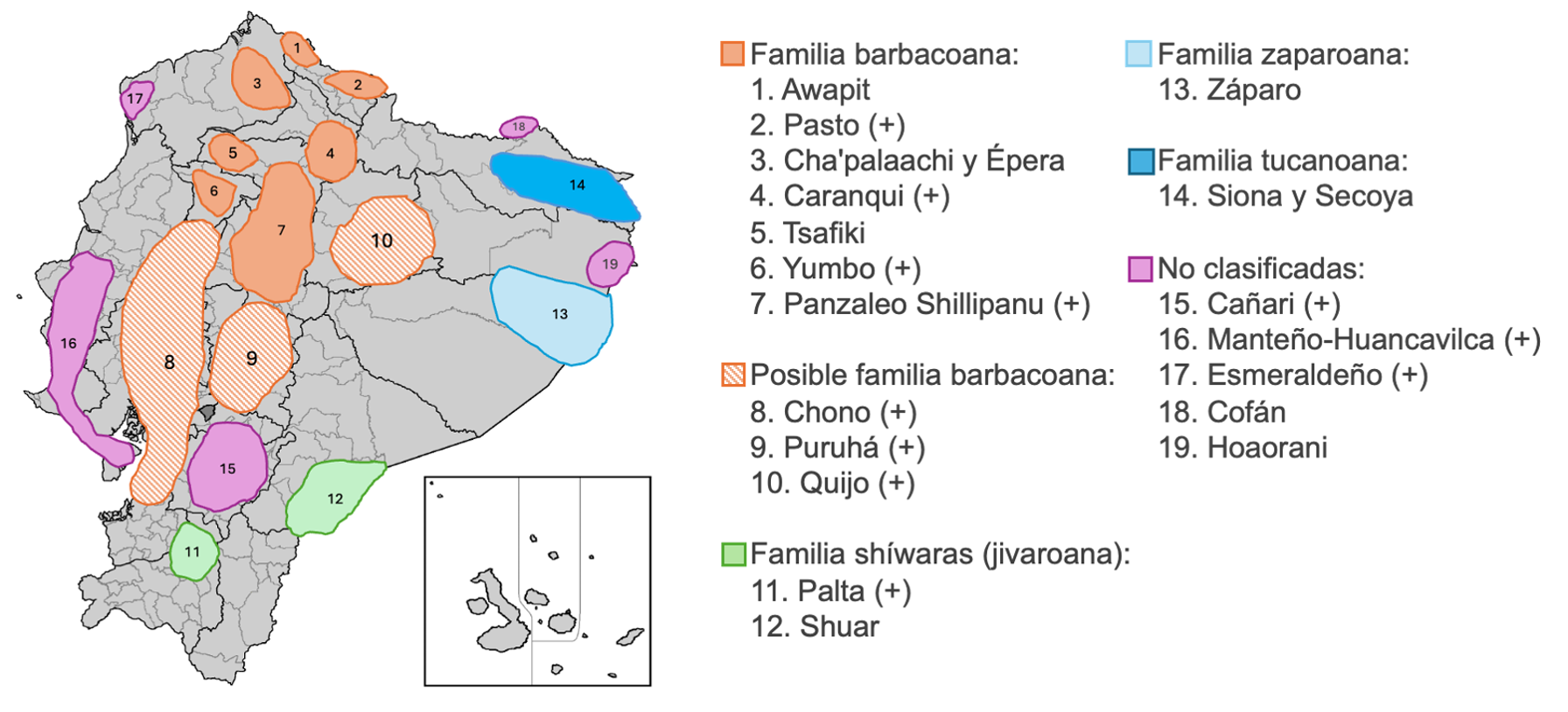

言語による先住民の分類としては、キチュア(Kichwa)、アチュアール=シアール(Achuar-Shiwiar)、チャパラーチ( Cha'palaachi)、コファン(Cofán)、トゥサチラ(Tsachila)、クアイケル(Cuaiquer)、セコヤ(Secoya)、シュアル(Shuar)、シオナ(Siona)、テテテ[絶滅](Tetete)、ワオラニ(Waorani)そして、スペイン語を話す先住民である。

★先住民インディヘナ裁判制度

「先

住民共同体、部族及び民族は、その居住地域において、祖先の伝統及び固有の権利に基づき、独自の司法権を行使し、先住民インディヘナ裁判を行うことが憲法

で認められている。但し、憲法裁判所の決定によると、この先住民インディヘナ裁判は一定の制限を受けるものとされており、もし生命又は個人的完全性等の基

本的権利の行使が侵害されるおそれがある場合、エクアドルの通常の刑事司法システムが、先住民インディヘナ裁判の決定を審査すべきこととされている。」——遠藤誠(n.d.)「エクアドルの法制度の概要」11pp.[pdf]

☆「エクアドルの先住民年表」よりインポート——利用資料は(新木 2014:313-317)ほか[→先住民運動と多民族国家]

|

1534 キトでルミニャウイがスペイン軍と戦う。スペイン人によるキト市建設 1563 キト王立アウデイエンシア設置 1780 11月 クスコ地方におけるトゥパック・アマルの蜂起 1781 3月 アルトペルーにおけるトゥパック・カタリの蜂起 1809 8月キトで独立宣百 1819 コロンビア、ベネズエラ、エクアドル、パナマなどを含む「グランコロンビア共和国(大グランビア)」が成立 1822 5月 ピチンチャの戦いでスペイン軍に勝利 1830 5月 エクアドル共和国成立(グランコロンビア共和国(大グランビア)の崩壊) 1852 9月 奴隷制廃止 1857 10月先住民税の廃止 1871 12月 フェルナンド・ダキレマの反乱 1895 6月 エロイ・アルファロによる自由主義革命の開始 1929 3月 憲法で女性参政権を規定 1934 ホルヘ・イカサ,『ワシプンゴjを出版 1937 8月 コムーナ法の公布 1941 7月 ペルーとの国境紛争 1944 8月 FEI (エクアドル先住民連盟)結成 1946 ドローレス・カクアンゴによる二言語学校設立(カヤンベ) 1961 9月 FCS (シュアール連盟)結成(1964 年に正式承認) 12月 農地改革を求める先住民の行進 1964 7月 農地改革法の公布(第一次農地改革の開始) 1967 3月 ラゴアグリオ油井発見 1968 11月 FENOC (農民組織全国連盟)結成 1972 2月 ロドリゲス軍事政権発足 2月 CEPE (エクアドル国営石油企業)設立 6月 ECUARUNARI (現エクアドル・キチュア民族連合)結成 8月 石油輸出の開始 1973 6月 エクアドル, OPEC 加盟 10月 農地改革法の公布(第二次農地改革の開始) 1974 9月 チンボラソ県における警察・軍との対立でラサロ・コンド死亡 1979 8月 民政移管(ロルドス政権発足),新憲法で非識字層に選挙権付与 OPIP (パスタサ先住民組織)結成 1980 3月 CISA (南米先住民審議会)設立(事務局はプーノ) 8月 CONFENIAE (エクアドル・アマゾン地域先住民連合)結成 10月 CONACNIE (エクアドル先住民調整審議会)設立 11月FEINE (エクアドル福音派先住民連盟)結成 1984 3月COICA (アマゾン盆地先住民組織調整組織)設立 1986 11月 CONAIE (エクアドル先住民連合)結成第1 回大会(キト) 1988 8月 ボルハ政権発足 11月 CONAIE 第2 回大会(カニャル) 11月 DINEIB (異文化間二言語教育局)設置異文化間二言語教育の開始 1989 6月 ILO (国際労働機関)による第169 号条約の採 1990 3月 ONHAE (エクアドル・アマゾン・ワオラニ民族組織)結成 5月 先住民によるサントドミンゴ教会占拠(キト) 6月 CONAIE 率いる先住民全国蜂起, CONAIE とボルハ政権の直接交渉開始 7月 OPIP 文書の策定(翌月.政府に提出) 7月 「先住民の抵抗の500 年」第1 回大陸会議(キト),キト宜言採択(The Declaration of Quito 1990) 12月 CONAIE 第3 回大会(グアヤキル),政府との交渉中断を決議 1991 4月 CONAIE と政府の交渉再開 7月 第1 回イベロアメリカ先住民サミット(キト) 10月 「先住民の抵抗の500 年」第2 回大陸会議(ケツァルテナンゴ・グアテマラ) 1992 4月 OPIP による「生活領域と生活のための行進」,アマゾン先住民の生活領域の合法化 6月 テキサコ,エクアドルより撤退 8月 マリアノ・クリカマ,グアモテ郡知事に就任 9月 FUT (労働者統一戦線)によるゼネスト実施 10月 「先住民の抵抗の500 年」第3 回大陸会議(マナグア) 10月 グアテマラのリゴベルタ・メンチュウ,ノーベル平和賞を受賞 11月 エクアドル, OPEC から脱退 1993 11月 アマゾン先住民などがニューヨークでテキサコを提訴(国際裁判の開始) 12月 CONAIE 第4 回大会(プヨ),選挙参加決議政治プロジェクト承認,マカス代表再選 1994 1月 メキシコでEZLN (サパティスタ民族解放軍)武装蜂起 6月 農業開発法に反対する先住民の抗議行動「生活のための動員」 CONAIE, 政治プロジェクトを公表 1995 3月 ペルーとの国境紛争が再燃 6月 MUPP-NP (パチャクティック運動)結成 7月 CICA (中米先住民審議会)設立 11月 国民投票でNo が勝利 1996 1月 ボリビアでモラレス政権発足 5月 ルイス・マカスなど国会議員当選,パチャクティック運動の躍進 7月 大統領選挙でプカラム当選 8月 ホセ・マリア・カバスカンゴがCONAIE 代表に就任 8月 アウキ・テイトゥアニャ,コタカチ郡知事に就任 10月 ラファエル・パンダム,文化民族相に任命 11月 CONAIE がパンダムを不承認 12月 CONAIE 第5 回大会(サラグロ).アントニオ・バルガスを代表に選出 1997 2月 ブカラム大統領が国会により解任,アラルコン臨時大統領が就任 4月 CONPLADEIN (先住民・アフロ系・民族マイノリティ企画開発審議会)設立 5月 制憲議会の招集 9月ニナ・パカリ,国会副議長に選出 9-10月 CONAIE による「自治と多民族性のための行進」 10月 CONAIE による全国民衆制憲議会の召集憲法改正案の策定に着手 1998 5月 エクアドル国会, ILO 第169 号条約を国内批准 6月 新憲法の発布,国家の多文化・多民族(エスニック)性を規定 8月 マワ政権発足 10月 ペルーとの和平合意で国境問題終結 12月 CONPLADEIN に代わりCODENPE (エクアドル先住民開発審議会)設立 1999 3月 経済政策に反対する先住民蜂起 8月 パチャクティック運動の第1 回全国大会(キト) 9月 DNSPI (先住民厚生局)設置 12月 CONAIE 第6 回大会(サントドミンゴ),バルガス代表の再選 2000 1月 マワ大統領によるドル化宣百 1月 全国民衆議会(キト)など全国各地で民衆議会設置 1月 先住民と軍人の蜂起でマワ政権崩壊,救国評議会の設置と解散 6月 先住民開発基金(FODEPI) 設立 8月 マリオ・コネホ,オタバロ郡知事に就任 9月 通貨のドル化実施 2001 2月 先住民蜂起 3月 先住民によるインガビルカ遺跡の占拠事件 9月 パチャクティック運動の第2 回全国大会(キト) 10月 CONAIE の召集による第1 回エクアドル先住民大会(キト) 11月 第6 回人ロセンサスの実施 CODENPE によるエクアドル先住民地図の作成 2002 11月 グティエレス候補,決選投票で大統領当選 2003 1月 グティエレス政権発足,パチャクティック運動の政権参加(パカリとマカスの入閣) 5月 テキサコ裁判,エクアドルに差し戻し 8月 パチャクティック運動の政権離脱 9月 パチャクティック運動の第3 回全国大会(リオバンバ) 2004 8月 先住民大学(UINPIAW) 設立 12月 CONAIE の召集による第2 回エクアドル先住民大会(オタバロ) 2005 4月 グティエレス政権の崩壊(ホラヒドスの反乱),パラシオ臨時政権の成立 8月 スクンビオス県とオレリャナ県で抗議行動 9月 パチャクティック運動の第4 回全国大会(アンバト) 2006 5月 アフロ系住民集団諸権利法の制定 5月 米国がFTA 交渉を中断 7月 ICAOI (アンデス先住民組織調整組織)設立(事務局はリマ) 10月 マカス,大統領選に出馬 11月 コレア候補決選投票で大統領当選 2007 1月 コレア政権発足 2月 対IMF 債務の繰上げ完済 4月 国民投票で制憲議会の召集を決定 4月 コレア大統領この頃から「21 世紀の社会主義」を提唱し始める 9月 制憲議会議員選挙 9月 国連総会における先住民権利宣言(UN-DRIPs)の採択 10月 ICONAIE による憲法草案の策定 10月 コレア政権がITT 鉱区での石油開発の中断を発表 10月 パチャクティック運動の第5 回全国大会(キト) 11月 制憲議会発足 11月 オレリャナ県で抗議行動(ダユマの弾圧事件) 12月 エクアドル, OPEC 再加盟 2008 1月 CONAIE の召集による第3 回エクアドル先住民大会(サントドミンゴ) 1月 グアヤキルで反政府デモ集会 3月 軍の侵入問題でコロンビアとの外交関係断絶(アンデス危機) 4月 鉱業指令(Mandato Minero) により鉱業開発プロジェクトを凍結 5月 南米諸国連合(UNASUR) 設立条約の採択(2011 年3 月発効,事務局キト) 7月 新憲法草案の国会承認 9月 国民投票で新憲法を承認 10月 新憲法制定 2009 1月 鉱業法の制定 1月 ボリビアで憲法制定 4月 大統領選挙でコレア再選(新憲法下での任期は1 回目) 4月 民衆連帯経済局(IEPS) 設置 4月 ボリビア共和国ボリビア多民族国へと国名変更 9月 水資源法と鉱業法に反対する先住民蜂起 11月 米軍によるマンタ基地の使用協定の期限切れ 11月 IBune Vivir に向けた国家計画2009-2013 の策定 2010 4月 水資源法に反対するCONAIE の抗議行動 5月 パチャクティック運動の第6 回全国大会‘(スクア,モロナ・サンティアゴ県) 6月 IALBA 首脳会議(オタバロ)に際しCONAIE はコレア政権と対立 8月 ヤスニーITT イニシアティブで国連環境計画(UNDP) と合意 9月 コレア大統領の訪日 9月 警官等による騒擾事件 11月 第7 回人ロセンサスの実施 11月 国会がダキレマとレオンを国家の英雄に認定 2011 2月 ラゴアグリオ高裁がシェブロン裁判で判決(80 億ドルの賠償命令) 3-4月 CONAIE の召集による第4 回エクアドル先住民大会(プヨ) 5月 大統領提案による国民投票の実施(10 項目を承認) 2012 2月 民衆連帯経済監督庁(SEPS) 設置 3月 コレア政権が中国系企業とミラドル鉱山の開発契約を締結 3月 CONAIE による「水•生活・尊厳を求める多民族行進」 7月 米州人権委員会がサラヤク裁判で判決(共同体領域における石油開発で国への賠償命令) 8月 ロンドンのエクアドル大使館におけるアサンジ(ウィキリークス創設者)亡命事件 2013 2月 コレア大統領の再選(任期は2017 年まで) 6月 Bune Vivir に向けた国家計画2013-2017 の策定 7月 鉱業法改正法の制定 8月 コレア大統領がヤスニーITT イニシアティブ断念を発表 10月 国会,第31 鉱区および第43 鉱区(ヤスニーITT 鉱区)の石油採掘が国民の利益であると決議 2013-2015 「2013

年5月に発足した第2次コレア政権は、メディアに対する規制の強化や大統領の三選を禁止する規定の改定を含む憲法改正を進めるなど、より強権的な政治運営

を進めた。一方で、経済を重視し、産業多角化を目指し、海外投資に対する関心を表明するなど、少しずつ開放経済に向けた改革を進めた。2014年後半から

の国際的な原油安とドル高を受けた財政の悪化や輸入規制等の対抗措置により国民生活に影響が出た。大統領による相続税改正法案等の国会への提出を契機とし

て、労働者、先住民等一部の国民の不満が高まり、2015年6月以降全国各地で抗議活動が継続的に発生した」[出典] 2014 2015 7月 7月5日から8日にかけて教皇フランシスコのエクアドル訪問[出典] 「同年、エクアドルは経済減速に見舞われ、国際収支の経常収支赤字と石油生産量の減少が発生した。様々な情報源がこの時期を経済危機またはモデル崩壊と呼んでいる」[出典] 2016 4月16日 「マグニチュード7.8の地震がマナビ州とエスメラルダス州の沿岸部を襲う」[出典] 2017 レ ニン・モレノ新大統領就任:「モレノ大統領は、対話と国民和解を呼びかけることから政権を開始し、前任者の政策やスタイルから次第に距離を置く姿勢を示し た。この新たなアプローチは、とりわけ市民参加の強化と、より親しみやすく透明性の高い国家の構築を目指した。また、前政権が対立関係にあった国々との関 係改善を図るなど、外交政策の転換も推進した。エクアドルは、ALBA およびUNASURといった、ラファエル・コレア政権時代に推進された組織から脱退した」[出典] 2017-2018年 「2017 年4月2日、与党モレノ候補(前副大統領)と野党ラッソ候補との間で大統領選挙決選投票が実施され、モレノ候補が51.15%を獲得して、大統領に当選し た。また、国会議員選挙では、議会(一院制)の中で国家同盟党(AP)が議席を減らし(100議席から74議席へ)、野党各党が議席を増やした。モレノ政 権は、コレア前政権を継承し、社会的再分配や社会資本整備を重要視するも、原油・一次産品価格低迷の中、ドル化経済の貿易収支の悪化への対応、財政の緊縮 と建て直し、対外債務の再交渉、産業の多角化と外国投資誘致等の課題に対応し、より自由、かつ開放的な経済を目指した。また、2018年2月4日には汚職 対策や憲法改正に関する立場を問う国民投票が実施された」[出典] 2018 「彼[レニン・モレノ]

の政権における重要な成果の一つは、2018年2月4日に実施された国民投票と国民投票の招集であった。この国民投票では、無期限の再選、市民参加・社会

統制評議会の再編、児童・青少年に対する性犯罪の時効廃止、保護地域・無開発地域・都市部における金属鉱業の禁止など、様々なテーマに関する7つの質問が

取り上げられた。その結果、政府が提案した案に対して市民の幅広い支持が示され、モレノ大統領にとって重要な政治的後押しとなり、国の制度的展望に変化を

もたらした。[86]

経済面では、モレノ政権は、石油価格の下落とパンデミックによって悪化した、受け継いだ困難な状況に直面した。多国間機関との合意による資金調達を模索

し、経済安定化のための措置を実施した。しかし、この期間中に貧困率と失業率は上昇した」[出典] 2019 2020 ※コロナパンデミックの開始 「2020 年の初めにエクアドルでは、2020年2月29日にマドリードから輸入された最初の症例により、COVID-19のパンデミックがエクアドルに到達したこ とが、消えない痕跡を残しました。[87] [88]この世界的な健康危機は、特に最初の数ヶ月間、同国に壊滅的な影響を与え、医療システムの不備を露呈し、グアヤキルなどの一部の都市では人道的 危機を引き起こしました。政府はウイルスの拡散を食い止めるため、全国的な非常事態宣言と外出禁止令を発令した。パンデミックへの対応は、医療物資の調達 における汚職疑惑も相まって、混乱を極めた」[出典]→「エクアドルにおけるCOVID-19のパンデミック」 2021 5月 ギジェルモ・ラッソ政権 「ギ ジェルモ・ラッソは、経済を活性化し、投資を呼び込み、雇用を創出すること、そして前政権が開始したCOVID-19ワクチン接種計画を継続することを公 約として政権に就いた。実際、彼の政権の最初の取り組みの一つはワクチン接種プロセスの加速であり、就任後100日間で人口の相当な割合に免疫を付与する ことに成功した」[出典] 2021-2023 「2021 年4月の大統領決選投票にて、ギジェルモ・ラッソ候補がコレア元大統領派である希望のための団結(UNES)のアラウス候補に僅差で勝利し、同年5月に大 統領に就任した。ラッソ大統領は、新型コロナワクチン接種計画を積極的に展開し、当初は高い支持率を維持したが、所得増税等を含む税制改革法成立等が影響 し、支持率を落とした。また、少数与党(全議席137議席中12議席)として厳しい国会運営を強いられる中、コロナ禍からの経済回復、2022年6月に起 きた先住民族主導の大規模全国デモ及び同団体との交渉、悪化する治安への対応等、政治運営は困難を極めた。2023年5月、野党勢力による大統領弾劾追求 の結果、ラッソ大統領は国会を解散し、同年8月に実施されることとなった大統領選挙及び国会議員選挙で国民の信を問うこととなった」[出典] 【暴 力犯罪の増加】「政治・エネルギー危機と並行して、エクアドルでは2021年から2023年にかけて暴力と治安の悪化が深刻化した。様々な指標が、殺人率 やその他の暴力犯罪の著しい増加を示しており、これは主に組織犯罪グループや麻薬密売組織の勢力拡大と縄張り争いに関連していた。刑務所でも虐殺や繰り返 される暴力事件が発生した。この治安の悪化は、市民にとって最大の懸念事項の一つとなり、政府にとっては継続的な課題となった」[出典] 2022 2023 5 月「国民議会による解任の可能性が差し迫る中、ラッソ大統領はこれまで利用されたことのない憲法上の手段、「相互解任」に訴えた。2023年5月17日、 ラッソは大統領令741号に署名し、国民議会を解散するとともに、大統領選挙と議会選挙の両方を含む早期総選挙の実施を宣言した。この決定は、憲法第 148条に基づき、自身と国民議会議員の任期を突然終了させ、新たな選挙プロセスにおいて国民に代表者を選出する権限を返還するものであった。選挙は 2023年8月に実施され、必要に応じて10月に決選投票が行われる」[出典] 2023-2025 「2023 年10月、大統領選挙決選投票にて、ダニエル・ノボア候補が左派候補に僅差で勝利し、ラッソ大統領の残りの任期(1年6か月)を引き継いで、同年11月に エクアドル史上最年少の大統領として就任した。ノボア政権では国内の治安改善が喫緊の課題となっている。2024年1月8日、犯罪組織リーダーの脱獄を機 に国内全土を対象に60日間の非常事態宣言を発令し、翌9日には大統領令にて国内が犯罪組織との武力衝突状態にある旨宣言。国内の治安回復に向け、大型刑 務所の建設や国境及び港の取締り強化等を進めている」[出典] 2023年11月:11月「ラッソ政権は2023年11月、選挙で当選したダニエル・ノボア大統領の就任により終了した。ノボアは、クロスオーバー死の適用後に召集された早 期選挙で勝利を収め、深刻な治安・経済危機という状況の中で政権を掌握した。これらの課題は、彼の政権運営の大部分を特徴づけるものとなった。政治界の新 人として登場したノボアは、2025年5月までの短縮された任期で大統領職に就いた」[出典] 2024 1 月「政権発足当初の最も衝撃的な出来事の一つは、2024年1月に発生した前例のない暴力の激化であった。国内主要犯罪組織のリーダーであるアドルフォ "フィト"・マシアスの脱走を受け、刑務所暴動、警察官拉致、爆破テロが相次いだ。[95] この状況は、グアヤキルにある公共テレビ局TC Televisiónの施設が、生放送中に武装集団による暴力的な襲撃を受けたことで、決定的な局面を迎えた。こうした事態を受け、ノボア大統領は「国内 武力紛争」の存在を宣言し、組織犯罪グループをテロ組織と指定し、軍隊にその制圧を命じた」[出典] 4

月:「ノボア政権は2024年4月21日に実施された国民投票と国民投票を推進した。この国民投票は11の質問で構成され、その大半は治安、司法、雇用に

関する問題だった。提案の中には、軍隊による国家警察への補完的支援、組織犯罪に関連する犯罪の刑罰強化、新たな犯罪の法定化などが含まれていた」[出典] 2025 「2025 年4月、大統領選挙決選投票にて、ダニエル・ノボア現職大統領が左派候補に10ポイント以上の差で勝利し、同年5月、大統領に再任された。引き続き、最優 先課題である治安改善及び公共事業及び民間部門に対する支援等による国内経済の活性化、若者の雇用創出に取組むとしている。また、渇水による水力発電不足 により2024年には長期間の計画停電を余儀なくされたことから、クリーンエネルギーのシステムを構築など、電力マトリックスの多様化を目指す」[出典] 2026 2027 2028 2029 2030 2031+ |

★1990年のキト宣言(The Declaration of Quito 1990)

| The Declaration of

Quito 1990 refers to the powerful statement issued by Indigenous

Nations and peoples at the "First Continental Conference '500 Years of

Indian Resistance'" in Quito, Ecuador, rejecting the colonial legacy

and demanding self-determination, autonomy, land rights, and an end to

oppression, marking a pivotal moment in pan-American Indigenous

solidarity against the quincentennial of European arrival. |

キト宣言1990は、エクアドルのキトで開催された「第1回大陸会議

『インディオ抵抗500年』」において先住民族国家と人民が発表した力強い声明を指す。この声明は植民地支配の遺産を拒否し、自己決定権、自治権、土地権

利、抑圧の終結を要求した。これはヨーロッパ人到来500周年を機に、汎米先住民連帯における決定的な瞬間を刻んだものである。 |

| Key Themes & Demands: Rejection of "Celebration": Indigenous peoples rejected the 500-year commemoration as a celebration of invasion, viewing it as an event of oppression and demanding liberation instead. Self-Determination & Autonomy: A core demand was the right to self-determination, leading to full autonomy, control over territories, and Indigenous self-government. Structural Change: They called for fundamental structural changes to existing nation-states to recognize inherent Indigenous rights, moving beyond mere constitutional reforms. Unity & Alliance: The declaration emphasized unity among Indigenous peoples and solidarity with other oppressed sectors (peasants, workers) to dismantle oppressive systems. Land & Resources: A strong stance against the commodification and exploitation of ancestral lands and natural resources by states and corporations. Repudiation of Debt: Demanded an end to foreign debt payments and reparations for historical injustices. |

主要なテーマと要求: 「祝賀」の拒否:先住民は侵略を祝うものとして500年記念を拒否し、抑圧の出来事と見なし、代わりに解放を要求した。 自己決定と自治:核心的な要求は自己決定権であり、完全な自治、領土の管理権、先住民族による自治政府の確立を導くものである。 構造的変革:既存の国民国家に対する根本的な構造的変革を求め、単なる憲法改正を超え、先住民族の固有の権利を認めることを主張した。 団結と連帯:宣言は、抑圧的な体制を解体するため、先住民間の団結と他の抑圧された層(農民、労働者)との連帯を強調した。 土地と資源:国家や企業による祖先の土地と天然資源の商品化・搾取に対する強い反対姿勢を示した。 債務の否認:対外債務の支払いの停止と、歴史的な不正に対する賠償を要求した。 |

| Significance: It was a foundational moment for the Continental Indigenous Movement, establishing a unified front for Indigenous rights in the Americas. It laid groundwork for future continental gatherings and demands for recognition within international forums, influencing later documents like the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP). It transformed a historical anniversary of conquest into a powerful call for liberation and decolonization. |

意義: これは大陸先住民運動の基盤となる瞬間であり、アメリカ大陸における先住民の権利のための統一戦線を確立した。 将来の大陸規模の集会や国際フォーラム内での承認要求の基盤を築き、国連先住民の権利に関する宣言(UNDRIP)のような後の文書に影響を与えた。 征服の歴史的記念日を、解放と脱植民地化を求める強力な呼びかけへと変えた。 |

☆方法論的含意

★以下は百科全書的情報( The Indigenous peoples in Ecuador or Native Ecuadorians などの資料)

| The Indigenous peoples in Ecuador or Native Ecuadorians

(Spanish: Ecuatorianos Nativos) are the groups of people who were

present in what became Ecuador before the Spanish colonization of the

Americas. The term also includes their descendants from the time of the

Spanish conquest to the present. Their history, which encompasses the

last 11,000 years,[2] reaches into the present; 7 percent of Ecuador's

population is of Indigenous heritage, while another 70 percent are

Mestizos of mixed Indigenous and European heritage.[3] Genetic analysis

indicates that Ecuadorian Mestizos are of three-hybrid genetic

ancestry.[4] |

エクアドルの先住民、またはエクアドル先住民(Indigenous peoples in Ecuador or Native Ecuadorians;

スペイン語: Ecuatorianos

Nativos)は、スペインによるアメリカ大陸植民地化以前にエクアドルに存在した人々のグループである。この言葉には、スペインによる征服時代から現

在に至るまでの子孫も含まれる。エクアドルの人口の7パーセントが先住民族であり、残りの70パーセントは先住民族とヨーロッパ人の混血であるメスティー

ソである[3]。遺伝子分析によると、エクアドルのメスチーソは3種雑種の遺伝的祖先を持っている[4]。 |

|

Shuar people in the park of Logroño, Morona-Santiago. モロナ・サンティアゴ県、ログローニョ公園に住むシュアール人。 1,301,887 (2022 census)[1] 7.69% of the Ecuadorian population Regions with significant populations Ecuador; Mainly: Sierra (Andean highlands) and Oriente (Eastern) Pichincha Province Pichincha 192,585[1] Chimborazo 178,754[1] Imbabura Province Imbabura 131,586[1] Morona-Santiago Province Morona-Santiago 112,722[1] Cotopaxi Province Cotopaxi 111,444[1] |

| Archaeological periods While archaeologists have proposed different temporal models at different times, the schematic currently in use divides prehistoric Ecuador into five major time periods: Lithic, Archaic, Formative, Regional Development, and Integration. These time periods are determined by the cultural development of groups being studied, and are not directly linked to specific dates, e.g. through carbon dating. The Lithic period encompasses the earliest stages of development, beginning with the culture that migrated into the American continents and continuing until the Late Pleistocene or Early Holocene. The people of this culture are known as Paleo-Indians, and the end of their era is marked by the extinction of the megafauna they hunted. The Archaic period is defined as "the stage of migratory hunting and gathering cultures continuing into the environmental conditions approximating those of the present."[5] During this period, hunters began to subsist on a wider variety of smaller game and increased their gathering activities.[6]: 13 They also began domesticating plants such as maize and squash, probably at "dooryard gardens."[6]: 13 In the Andean highlands, this period lasted from 7000-3500 BP. The Formative Period is characterized by "the presence of agriculture, or any other subsistence economy of comparable effectiveness, and by the successful integration of such an economy into well-established, sedentary village life."[5] In Ecuador, this period is also marked by the establishment of trade networks[6]: 16 and the spread of different styles of pottery.[6]: 19 It began in about 3500 and ended around 2200 BP. Regional Development is the period, dating roughly 2200–1300 BP, of the civilizations of the Sierra, described as "localized but interacting states with complex ideologies, symbol systems, and social forms." The people of this period practiced metallurgy, weaving, and ceramics.[7] The Integration Period (1450 BP—450 BP) "is characterized by great cultural uniformity, the development of urban centres, class-based social stratification, and intensive agriculture."[8] The Integration Period ends and the historic era begins with the Inca conquest. |

考古学的時代 考古学者たちは時代ごとに異なる時間モデルを提唱してきたが、現在使われている図式では、先史時代のエクアドルを大きく5つの時代に分けている: 石器時代、アルカイック時代、形成期、地域発展期、統合期である。これらの時期は、研究対象の集団の文化的発展によって決定されるものであり、炭素年代測 定などによる特定の年代と直接的にリンクするものではない。 石器時代には、アメリカ大陸に移住した文化から始まり、更新世後期または完新世前期まで続く、最も初期の発展段階が含まれる。この文化の人々は古インディアンとして知られ、彼らの時代の終わりは、彼らが狩猟していた巨大動物の絶滅によって示される。 アルカイック期は、「移動狩猟採集文化が、現在の環境条件に近い状態まで続いた段階」と定義されている[5]。この時期、狩猟者はより多種多様な小動物の 狩猟で生計を立てるようになり、採集活動を活発化させた[6]: 13 また、トウモロコシやカボチャのような植物を家畜化し始め、おそらく「家畜園」で栽培されるようになった[6]: 13 アンデス高地では、この時期は7000-3500BPまで続いた。 形成期の特徴は、「農業、あるいはそれに匹敵するような他の自給自足経済が存在し、そのような経済が確立された定住的な村落生活にうまく統合されたこと」[5]である: 16と異なる様式の陶器が広まった[6]: 19 約3500BPに始まり、約2200BPに終わる。 地域的発展とは、おおよそ2200-1300BPにさかのぼるシエラ文明の時代であり、「複雑なイデオロギー、象徴体系、社会形態をもつ、局地的だが相互作用のある国家」として説明される。この時代の人々は、冶金、織物、陶器を実践していた[7]。 統合期(1450BP-450BP)は、「文化的な均一性、都市中心部の発展、階級に基づく社会階層、集約的な農業によって特徴づけられる。 |

| Paleo-Indians The oldest artifacts discovered in Ecuador are stone implements discovered at 32 Cotton Pre-ceramic (Paleolithic) archaeological sites in the Santa Elena Peninsula. They indicate a hunting and gathering economy, and date from the Late Pleistocene epoch, or about 11,000 years ago. These Paleo-Indians subsisted on the megafauna that inhabited the Americas at the time, which they hunted and processed with stone tools of their own manufacture. Evidence of Paleoindian hunter-gatherer material culture in other parts of coastal Ecuador is isolated and scattered.[9] Such artifacts have been found in the provinces of Carchi, Imbabura, Pichincha, Cotopaxi, Azuay, and Loja.[10] Despite the existence of these early coastal settlements, the majority of human settlement occurred in the Sierra (Andean) region, which was quickly populated.[11][12] One such settlement, remains of which were found at the archaeological site El Inga, was centered at the eastern base of Mount Ilaló, where two basalt flows are located. Due to agricultural disturbances of archaeological remains, it has been difficult to establish a consistent timeline for this site. The oldest artifacts there discovered, however, date to 9,750 BP.[11] In the South, archaeological discoveries include stone artifacts and animal remains found in the Cave of Chobshi, located in the cantón of Sigsig, which date between 10,010 and 7,535 BP. Chobshi also provides evidence of the domestication of the dog. Another site, Cubilán, rests on the border between Azuay and Loja provinces. Scrapers, projectile points, and awls discovered there date between 9,060 and 9,100 BP, while vegetable remains are up to a thousand years older. In the Oriente, human settlements have since at least 2450 BP.[13] Settlements that probably date from this period have been found in the provinces of Napo, Pastaza, Sucumbíos, and Orellana.[13] However, most of the evidence recovered in the Oriente suggest a date of settlement later than in the Sierra or the Coast. |

古代インディアン エクアドルで発見された最古の遺物は、サンタ・エレナ半島の32の綿先土器(旧石器)遺跡で発見された石器である。これらは狩猟採集経済を行っていたこと を示すもので、後期更新世、つまり約11,000年前のものである。これらの古インディアンたちは、当時アメリカ大陸に生息していた巨大動物を捕獲し、自 分たちで作った石器で加工して食べていた。 エクアドル沿岸部の他の地域では、古インディオの狩猟採集民の物質文化の証拠が孤立して散在している。 このような初期の海岸集落の存在にもかかわらず、人類の定住の大部分はシエラ(アンデス)地方で発生し、急速に人口が増加した[11][12]。そのよう な集落のひとつである遺跡エル・インガで発見された遺跡は、2つの玄武岩流があるイラロ山の東麓を中心としていた。農業による遺跡の攪乱のため、この遺跡 の年代を特定することは困難であった。しかし、そこで発見された最古の遺物は、9,750BPのものである[11]。 南部では、シグシグ州にあるチョブシの洞窟で、10,010~7,535BPの石器や動物の遺骸が発見された。また、チョブシ洞窟からは、犬が家畜化され た証拠も発見されている。もう一つの遺跡キュビランは、アズアイ州とロハ州の境にある。そこで発見された擦過器、尖頭器、アワルは 9,060~9,100BPのもので、野菜の遺跡は1,000年前のものである。 オリエンテでは、少なくとも2450BP以降に人類が定住していた[13]。ナポ県、パスタサ県、スクンビオス県、オレリャーナ県でこの時代のものと思わ れる集落が発見されている[13]。しかし、オリエンテで発見された証拠のほとんどは、シエラやコーストよりも後の時代に定住したことを示唆している。 |

| Origins of agriculture The end of the Ice Age brought changes to the flora and fauna, which led to the extinction of the large game hunted by Paleo-Indians, such as giant sloth, mammoth, and other Pleistocene megafauna. Humans adapted to the new conditions by relying more heavily on farming. The adoption of agriculture as the primary mode of subsistence was gradual, taking up most of the Archaic period. It was accompanied by cultural changes in burial practices, art, and tools. The first evidence of agriculture dates anywhere from the Preboreal Holocene (10,000 years ago)[9] to the Atlantic Holocene (6,000 years ago).[2][6] Some of the first farmers in Ecuador were the Las Vegas culture of the Santa Elena Peninsula/, who, in addition to making use of the abundant piscine resources, also contributed to the domestication of several beneficial plant species, including squash.[9] They engaged in ritual burial and intensive gardening. The Valdivia culture, an outgrowth of the Las Vegas culture, was an important early civilization. While archaeological finds in Brazil and elsewhere have supplanted those at Valdivia as the earliest-known ceramics in the Americas, the culture retains its importance due to its formative role in Amerindian civilization in South America, which is analogous to the role of the Olmeca in Mexico.[11] Most of the ceramic shards from the Early Valdivia date to about 4,450 BP (although some may be from up to 6,250 BP), with artifacts from the later period of the civilization dating from about 3,750 BP. Ceramics were utilitarian, but also produced pieces of very original art, like the small feminine figures referred to as "Venuses." The Valdivia people farmed maize, a large bean (now rare) of the Canavalia family, cotton, and achira (Canna edulis). Indirect evidence suggests that maté, coca, and manioc were also cultivated. They also consumed substantial amounts of fish. Archaeological evidence from the Late Valdivia shows a decline in life expectancy to approximately 21 years. This decline is attributed to an increase in infectious disease, accumulation of waste, water pollution, and a deterioration in diet, all of which are associated with agriculture itself.[14] In the Sierra, people cultivated locally developed crops, including tree bean Erythrina edulis, potatoes, quinoa, and tarwi. They also farmed crops that originated in the coastal regions and in the North, including ají, peanuts, beans, and maize. Animal husbandry kept pace with agricultural development, with the domestication of the local animals llama, alpaca, and the guinea pig, as well as the coastal Muscovy duck. The domestication of camelids during this period laid the basis for the pastoral tradition that continues to this day. In the Oriente, evidence of maize cultivation discovered at Lake Ayauchi dates from 6250 BP.[6] In Morona-Santiago province, evidence of Regional Development period culture was discovered at the Upano Valley sites of Faldas de Sangay, also known as the Sangay Complex or Huapula, as well as at other nearby sites. These people created ceramics, farmed, and hunted and gathered.[13] They also built large earthen mounds, the smallest of which were used for agriculture or housing, and the largest of which had ceremonial functions. The hundreds of mounds spread over a twelve square kilometer[15] area at Sangay demonstrate that the Oriente was capable of supporting large populations. The lack of evidence of kings or "principal" chiefs and also challenges the notion that cultural creations such as monuments require centralized authority.[16] |

農業の起源 氷河期の終わりは動植物に変化をもたらし、古インディアンが狩猟していたオオナマケモノやマンモスなどの更新世巨獣類は絶滅した。人類は農耕に依存するこ とで、新しい環境に適応した。自給自足の主要な手段として農耕が採用されたのは徐々にで、アルカイック期の大半を占めた。農耕は、埋葬習慣、芸術、道具な どの文化的変化を伴った。 農耕の最初の証拠は、有史以前の完新世(10,000年前)[9]から大西洋完新世(6,000年前)[2][6]にまで遡る。 エクアドルで最初の農耕民の一部は、サンタ・エレナ半島のラスベガス文化人であり、彼らは豊富な魚類資源を利用することに加えて、カボチャを含むいくつかの有益な植物種の家畜化に貢献した[9]。 ラスベガス文化から発展したバルディビア文化は、初期の重要な文明であった。アメリカ大陸で最古の陶磁器として知られるバルディヴィアの陶磁器は、ブラジ ルやその他の場所で考古学的に発見された陶磁器に取って代わられたが、南アメリカのアメリカインディアン文明において、メキシコのオルメカの役割に類似し た形成的な役割を果たしたため、この文化はその重要性を保っている[11]。初期バルディヴィアの陶磁器片のほとんどは約4,450BPのものであり(中 には6,250BPのものもあるが)、文明後期の遺物は約3,750BPのものである。陶磁器は実用的であったが、「Venuses 」と呼ばれる小さな女性像のような非常に独創的な芸術品も作られた。 バルディビア人は、トウモロコシ、カナバリア科の大型豆(現在では希少)、綿花、アキラ(Canna edulis)を栽培していた。間接的な証拠によると、マテ、コカ、マニオクも栽培されていたようだ。また、かなりの量の魚を消費していた。バルディビア 後期の考古学的証拠からは、平均寿命が約21歳まで低下したことがわかる。この低下は、伝染病の増加、廃棄物の蓄積、水質汚染、食生活の悪化に起因してお り、これらはすべて農業そのものに関連している[14]。 シエラでは、人々は木豆Erythrina edulis、ジャガイモ、キヌア、タルウィなど、地元で開発された作物を栽培していた。また、アヒ、ピーナッツ、豆、トウモロコシなど、沿岸地域や北部 で生まれた作物も栽培していた。畜産は農業の発展と歩調を合わせ、地元の動物であるリャマ、アルパカ、モルモットを家畜化し、沿岸部のムスコビーダックも 家畜化した。この時期にラクダ科の動物が家畜化され、今日まで続く牧畜の伝統の基礎が築かれた。 オリエンテ州では、綾内湖で発見されたトウモロコシ栽培の証拠が6250BPのものである[6]。モロナ・サンチャゴ州では、サンガイ・コンプレックスま たはワプラとしても知られるファルダス・デ・サンガイのウパノ渓谷の遺跡や、その他の近隣の遺跡で、地域開発期の文化の証拠が発見された。これらの人々は 陶器を作り、農耕をし、狩猟採集をしていた[13]。彼らはまた大きな土塁を築き、小さなものは農耕や住居に使われ、大きなものは儀式に使われた。サンガ イの12平方キロメートル[15]の地域に広がる数百の塚は、オリエンテが大規模な人口を維持する能力があったことを示している。また、王や「主要な」首 長の証拠がないことから、遺跡のような文化的創造物には中央集権的な権威が必要であるという考え方にも疑問を投げかけている[16]。 |

| Development of metallurgy The period from 2450 BP—1450 BP is known as the "Regional Development" period, and is marked by the development of metalworking skills. The artisans of La Tolita, an island in the estuary of the Santiago River, made alloys of platinum and gold, fashioning the material into miniatures and masks. The Jama-Coaque, Bahía, Guangala, and Jambalí also practiced metalwork in other areas of the Ecuadorian coast.[17] These goods were traded though mercantile networks. |

冶金の発展 紀元前2450年から紀元前1450年の間は「地域開発」の時代と呼ばれ、金属加工技術の発展が顕著である。サンティアゴ川河口の島、ラ・トリタの職人た ちは、プラチナと金の合金を作り、ミニチュアや仮面に加工した。ジャマ・コアケ族、バイア族、グアンタラ族、ジャンバリ族もエクアドル沿岸の他の地域で金 属加工を行っていた。 |

Pre-Inca era Map showing the indigenous languages spoken in Ecuador in the Pre-Inca era Prior to the invasion of the Inca, the Indigenous societies of Ecuador had complex and diverse social, cultural, and economic systems. The ethnic groups of the central Sierra were generally more advanced in organizing farming and commercial activities, and the peoples of the Coast and the Oriente generally followed their lead, coming to specialize in processing local materials into goods for trade. The coastal peoples continued the traditions of their predecessors on the Santa Elena peninsula. They include the Machalilla, and later the Chorrera, who refined the ceramicism of the Valdivia culture. The economy of the peoples of the Oriente was essentially silvicultural, although horticulture was practiced. They extracted dyes from the achiote plant for face paint, and curare poisons for blowgun darts from various other plants. Complex religious systems developed, many of which incorporated (or perhaps originated from) the use of hallucinogenic plants such as Datura and Banisteriopsis. They also made coil ceramics. In the Sierra, the most important groups were the Pasto, the Caras, the Panzaleo, the Puruhá, the Cañari, and the Palta.[18][page needed] They lived on hillsides, terrace farming maize, quinoa, beans, potatoes and squash, and developed systems of irrigation. Their political organization was a dual system: one of chieftains, the other, a land-holding system called curacazgo, that regulated the planting and harvesting of multiple cycles of crops. While some historians have referred to this system as the "Kingdom of Quito", it did not approach the level of political organization of the state. |

プレ・インカ時代 プレ・インカ時代にエクアドルで話されていた先住民族の言語を示す地図 インカの侵略以前、エクアドルの先住民社会は複雑で多様な社会、文化、経済システムを持っていた。シエラ中央部の民族は、一般的に農業と商業活動の組織化 においてより進んでおり、海岸とオリエンテの民族は一般的に彼らに倣い、地元の材料を加工して交易品にすることに特化するようになった。 沿岸の人々はサンタ・エレナ半島の先人たちの伝統を受け継いだ。バルディビア文化の陶磁器を改良したマチャリャ人、後のチョレラ人などがその一例である。 オリエンテの人々の経済は、園芸も行われていたが、基本的には養蚕であった。彼らはアチョーテという植物から顔に塗るための染料を抽出し、他のさまざまな 植物から吹き矢用のクラーレ毒を抽出した。複雑な宗教体系が発達し、その多くはダチュラやバニステリオプシスといった幻覚作用のある植物の使用を取り入れ ていた(あるいはそこから生まれたのかもしれない)。彼らはコイルセラミックも作っていた。シエラでは、最も重要なグループはパスト族、カラス族、パンザ レオ族、プルハ族、カニャリ族、パルタ族であった[18][要出典]。彼らは丘の斜面に住み、トウモロコシ、キヌア、豆、ジャガイモ、カボチャを段々畑で 栽培し、灌漑システムを開発した。彼らの政治組織は二重システムであり、ひとつは酋長、もうひとつはcuracazgoと呼ばれる土地所有システムで、複 数のサイクルの作物の植え付けと収穫を規制していた。このシステムを「キト王国」と呼ぶ歴史家もいるが、国家の政治組織レベルには達していなかった。 |

| Economy Using the system of multicyclic agriculture, which allowed them to have year-long harvests of a wide variety of crops by planting at a variety of altitudes and at different times, the Sierra people flourished. Generally, an ethnic group farmed the mountainside nearest to it. Cities began to specialize in the production of goods, agricultural and otherwise. For this reason, the dry valleys, where cotton, coca, ají (chili peppers), indigo, and fruits could be grown and where salt could be produced, gained economic importance. Sometimes, tribes farmed lands outside their immediate purview. These goods were then traded in a two-tiered market system. Free commerce took place in markets called "tianguez", and was the means by which ordinary individuals fulfilled their need for tubers, maize, and cotton. Directed commerce, however, was undertaken by specialists called mindala under the auspices of a curaca. They also exchanged goods at the tianguez, but specialized in products that had ceremonial purposes, such as coca, salt, gold, and beads. Seashells were sometimes used as currency in places such as Pimampiro in the far North. Salt was used in other parts of the Sierra, and in other places where salt was abundant, such as Salinas. In this manner, the Pasto and the Caras undertook their existence in the Chota Valley, the Puruhá in the Chanchán riverbasin, and the Panzaleos in the Patate and Guayallabamba valleys. In the coastal lowlands, the Esmeralda, the Manta, the Huancavilca, and the Puná were the four major groups. They were seafarers, but also practiced agriculture and trade, both with each other and with peoples of the Sierra.[18][page needed] The most important commodity they provided, however, were Spondylus shells, which was a symbol of fertility.[17] In areas such as Guayas and Manabí, small beads called chiquira were used as currency. Also following the lead of the Sierra peoples, the people of the Oriente began congregating around sites where cotton, coca, salt, and beads could be more easily produced for trade. Tianguez developed in the Amazon forest, and were visited by mindala from the Sierra. |

経済 シエラ族は、標高の異なる場所に時期をずらして作付けすることで、多種多様な作物を1年を通して収穫できる多収穫農法を用いて繁栄した。一般的に、ある民 族はその民族に最も近い山腹で農業を営んだ。都市は、農産物やその他の商品の生産に特化するようになった。そのため、綿花、コカ、アヒ(唐辛子)、藍、果 物の栽培や塩の生産が可能な乾燥した渓谷が経済的に重要視されるようになった。時には、部族が自分たちの管轄外の土地を耕作することもあった。これらの商 品は、2段階の市場システムで取引された。 自由貿易は「ティアンゲス」と呼ばれる市場で行われ、一般個人が塊茎、トウモロコシ、綿花の需要を満たす手段であった。一方、直接取引は、クラーカの支援 のもと、ミンダラと呼ばれる専門家によって行われた。彼らもティアンゲスで商品を交換したが、コカ、塩、金、ビーズなど、儀式に使われる商品に特化してい た。北部のピマンピロなどでは、貝殻が通貨として使われることもあった。塩はシエラの他の地域や、サリナスなど塩の豊富な場所で使われた。 このようにして、パスト族とカラス族はチョタ渓谷で、プルハ族はチャンチャン川流域で、パンザレオス族はパタテ渓谷とグアヤラバンバ渓谷でその存続を請け負った。 沿岸の低地では、エスメラルダ族、マンタ族、フアンカビルカ族、プナ族が4大集団であった。しかし、彼らが提供した最も重要な商品は、豊饒の象徴であった スポンディルス貝であった[17]。グアヤスやマナビのような地域では、チキーラと呼ばれる小さなビーズが通貨として使用された。 シエラ族に倣い、オリエンテの人々も綿花、コカ、塩、ビーズをより簡単に生産できる場所に集まり、交易を始めた。ティアンゲスはアマゾンの森で発展し、シエラからマインダラが訪れた。 |

| Political organization The extended family, in which polygyny was common, was the basic unit of society. The extended family group is referred to by the Kichwa word "ayllu", although this type of organization predates the arrival of Quechua speakers. Two political systems were built on the basis of the ayllu: the curacazgo and the cacicazgo. Each curacazgo is made up of one or more ayllu. The Ecuadorian ayllus, unlike in the Southern Andes, were small, made up of only about 200 people, although the larger ones could reach up to 1,200 members. Each ayllu had its own authority, although each curaca also answered to a chief (cacique), who exercised power over the curacazgo. The cacique's power depended on his ability to mobilize manual labor, and was sustained by his ability to distribute highly-valued goods to the members of his curaca. |

政治組織 一夫多妻制が一般的な拡大家族が社会の基本単位であった。キチュワ語で「アイリュ」と呼ばれるが、このような家族はケチュア語族の到来以前から存在した。 アイリュを基礎として、クラカズゴとカチカズゴという2つの政治体制が築かれた。各クラカズゴは1つ以上のアイリュで構成されている。エクアドルのアイ リュは、南アンデスのアイリュとは異なり、200人ほどの小さなアイリュであった。各アイリュは独自の権限を持っていたが、各クラーカはクラーカズゴに対 して権力を行使する首長(カチケ)にも従っていた。カチケの権力は肉体労働を動員する能力に依存し、クラーカのメンバーに高価な商品を分配する能力によっ て維持されていた。 |

| Religion Local beliefs and practices co-existed those practiced regionally, which allowed each ethnic group to maintain its own religious identity while interacting, especially commercially, with neighboring groups. Some regional commonalities were the solar calendar, which marked the solstices and equinoxes, and veneration of the sun, moon, and maize. |

宗教 各民族は独自の宗教的アイデンティティを維持しながら、特に近隣の民族と商業的な交流を深めていた。地域的な共通点としては、夏至と分点を記す太陽暦や、太陽、月、トウモロコシへの崇拝があった。 |

| Inca conquest The Inca empire expanded into what later became Ecuador during the reign of Pachacuti Inca Yupanqui, who began the northward conquest in 1463. He gave his son Topa control of the army, and Topa conquered the Quitu and continued coastward. Upon arriving, he undertook a sea voyage to either the Galápagos or the Marquesas Islands. Upon his return, he was unable to subdue the people of Puná Island and the Guayas coast. His son Huayna Capac, however, was able to subsequently conquer these peoples, consolidating Ecuador into "Tawantinsuyu", the Inca Empire.[18][page needed] Many tribes resisted the imperial encroachment, in particular the Cañari in the south, near modern-day Cuenca,[19] and the Caras and the Quitu in the North. However, the Inca language and social structures came to predominate, particularly in the Sierra. To reduce the opposition to their rule, one of the Inca's tactics included uprooting groups of Quechua-speakers loyal to the empire and resettling them in areas that offered resistance, a system called mitma. The Saraguros in Loja province may have their origin from mitmas relocated from other parts of the Inca Empire. Some scholars dispute the Inca heritage of Indigenous people of Ecuador.[20] |

インカの征服 インカ帝国は、1463年に北方征服を開始したパチャクチ・インカ・ユパンキの治世に、後のエクアドルへと拡大した。彼は息子のトパに軍の指揮権を与え、 トパはキトゥを征服して海岸沿いに進んだ。到着後、彼はガラパゴス諸島かマルケサス諸島への航海に出た。帰国後、彼はプナ島とグアヤス海岸の人々を征服す ることはできなかった。しかし息子のワイラ・カパックは、その後これらの民族を征服し、エクアドルを「タワンティンスーユ」と呼ばれるインカ帝国に統合し た[18][要ページ]。 多くの部族が帝国の侵攻に抵抗し、特に南部、現在のクエンカ近郊のカニャリ族[19]、北部のカラス族とキトゥ族はそれに抵抗した。しかし、特にシエラで はインカの言語と社会構造が優勢となった。支配への反発を抑えるため、インカの戦術のひとつに、帝国に忠誠を誓うケチュア語話者の集団を根こそぎにし、抵 抗勢力となる地域に再定住させるというミトマと呼ばれる制度があった。ロハ州のサラグロ族は、インカ帝国の他の地域から移されたミトマに起源を持つのかも しれない。 エクアドルの先住民がインカの遺産を持っていることに異論を唱える学者もいる[20]。 |

| Spanish conquest In 1534, at the time of the arrival of the first columns of Spanish conquistadores, the population of the present day territories of Ecuador is believed to border the figure of one million inhabitants. This might have been a result of epidemics of smallpox and diphtheria that spread in the Andes after the first contacts with Spanish explorers and their livestock. According to early Spanish chronicles the Inca Huayna Capac died of smallpox and then the territories of Collasuyo and central Peru so a period of civil war for the control of the royal household between two brothers each an heir to the dominions of their respective maternal feudal lands. Huáscar was a prince born to a noble family of Cuzco and Atahualpa was a son from a noble family of the Quitus. The quitus were a tribe that formed an alliance with the Incas during the conquest of Huayna Capac. Most important in this civil war was the participation of Huayna Capac generals on the side of Athaulpa's faction, probably due to the late sovereign wish. |

スペインの征服 1534年、スペイン人征服者の最初の隊列が到着したとき、現在のエクアドル領土の人口は100万人に達していたと考えられている。これは、スペイン人探 検家やその家畜との最初の接触の後、アンデス山脈で蔓延した天然痘やジフテリアの伝染病の結果だったのかもしれない。スペインの初期の年代記によると、イ ンカのワイラ・カパックは天然痘で死亡し、その後コラスヨとペルー中央部の領土は、それぞれの母方の封建領地の後継者である2人の兄弟の間で、王室の支配 権をめぐる内戦が繰り広げられた。 フアスカルはクスコの貴族に生まれた王子であり、アタハルパはキトゥス族の貴族の息子であった。キトゥス族はワイカパック征服の際にインカと同盟を結んだ 部族である。この内戦で最も重要だったのは、フアイナ・カパックの将軍たちがアタルパの派閥に参加したことで、おそらく君主の故意によるものであろう。 |

| Republican era Rubber boom The 19th century marked a time in history when the need for rubber came into high demand in the world.[21] Many Western Territories including America wanted to produce Rubber Industries in desire to produce economic prosperity. They also expressed an alternative goal, which was to also make better the region they will be in partnership with by improving their land and their economic status as well.[21] Reasons as to why they decided to obtain partnership with the Amazonian region was for multiple reasons. One of the reasons was that the location was ideal. Two of the most high quality rubber trees grew in that region; the Hevea tree and the Castilloa. tree[22] the Hevea tree was only able to be used 6 month out of the year while the Castilloa was able to be used the whole year.[22] To begin the trading system, the Western territories began to obtain discourse with the Mestizos of the land which were known to be the more prestigious of the different groups residing in Ecuador. They became highly tied into the trading system that was created. There was fast money involved in this system that attracted the Mestizos. Economic prosperity seemed promising. As the rubber industry flourished many other factors came to surface in the system of Rubber production. Because of the high demand for rubber at the time, the Mestizos who became known as the Caucheros (rubber barons) decided that they needed to obtain an abundant number of workers that would work for low wages.[21] The Indigenous population soon came to mind because of a couple of factors. One was due to the fact that they seemed the best fit to perform the labor. They knew the lands on which they would work because of their long history of living on the land. They were well adapted to the climate and familiar with means of survival like hunting and gathering.[21] The enslavement of the Indigenous people soon became an epidemic. Natives were taken from their homes by a group called the Muchachos who were African men hired by the Caucheros to do their dirty work.[21] They were in turn forced to work in the rubber industries by fear and intimidation and were put on a rubber quota with time constraints and were expected to meet the demands. If the quotas were not met they were punished. Punishments by the Muchachos were very severe and brutal. Common punishments including flogging, hanging, and being put into a cepo.[21] When the workers were put into a cepo they were chained in pain inflicting positions and left without food and water for an extended period of time.[21] More extreme punishments included the shooting workers if they tried to escape or became too ill to work.[21] The pay for their hard labor was minimal. They were put on what was called a debt-penoage where they had to work for a long period of time in order to gain funds to pay back debt they owned to the Caucheros for supplies that they were given for their daily tasks such as tools to work, clothes, and food.[21] The low compensation for their labor often led to working their whole life for the rubber barons. They usually received a small item that they were able to keep, like a hammock, and the rest was given straight to the employer.[21] There was very little Government intervention thanks to bribery that got local officials to overlook what was occurring and the fear of being attacked by the Amerindians.[21] The end of the Rubber Boom was in 1920 when the prices of rubber dropped. The enslavement of the Indigenous people ceased with the end of the rubber boom. |

共和国時代 ゴムブーム 19世紀は、世界でゴムの需要が急増した歴史的な時代であった[21]。アメリカを含む多くの西洋諸国は、経済的繁栄を求めゴム産業の生産を望んだ。彼ら はまた、提携する地域の土地と経済状況を改善することで、その地域をより良くするという別の目標も表明した。[21] アマゾン地域との提携を選んだ理由は複数あった。第一に立地条件が理想的だった。この地域には最高品質のゴムノキが二種類生育していた。ヘベアノキとカス ティリョアノキである[22]。ヘベアノキは年間6か月しか利用できないが、カスティリョアノキは通年利用が可能だった。[22] 貿易システムを開始するため、西部地域はエクアドルに居住する様々な集団の中でも特に名声の高いメスティソ層との対話を始めた。彼らは構築された貿易シス テムに深く関与するようになった。このシステムには即金が生じる仕組みがあり、メスティソ層を惹きつけた。経済的繁栄は有望に見えた。ゴム産業が繁栄する につれ、ゴム生産システムには多くの問題が表面化した。当時のゴム需要の高さから、カウチェロス(ゴム王)として知られるようになったメスティソたちは、 低賃金で働く労働者を大量に確保する必要があると判断した[21]。いくつかの要因から、すぐに先住民が候補として浮上した。一つは、彼らが労働に最も適 しているように見えたからだ。彼らはその土地で長く暮らしてきたため、働く土地をよく知っていた。気候にもよく適応しており、狩猟や採集といった生存手段 にも精通していたのだ[21]。先住民の奴隷化はすぐに蔓延した。ムチャチョスと呼ばれる集団によって、先住民は故郷から連れ去られた。ムチャチョスはカ ウチェロスに雇われたアフリカ人男性で、彼らの汚い仕事を担っていたのだ。[21] 先住民は恐怖と威圧によってゴム産業での労働を強制され、時間制限付きのゴム生産ノルマを課され、その要求を満たすことが求められた。 ノルマを達成できなかった場合、彼らは罰せられた。ムチャチョスによる処罰は極めて厳しく残忍だった。一般的な罰には鞭打ち、絞首刑、足枷(セポ)への拘 束が含まれた[21]。労働者が足枷に嵌められると、苦痛を伴う姿勢で鎖で繋がれ、長期間にわたり食料も水も与えられなかった。[21] さらに過酷な処罰として、逃亡を試みた労働者や、病で働けなくなった労働者を射殺するケースもあった。[21] 過酷な労働に対する賃金はごくわずかだった。彼らは「債務ペノーアージュ」と呼ばれる制度下に置かれ、カウチェロから支給された日用品(作業道具、衣服、 食料など)の代金を返済するため、長期間労働を強いられた。[21] 労働に対する低賃金のため、彼らはゴム王のために一生働き続けることが多かった。通常、ハンモックのような小さな品物だけを手に入れられ、残りは直接雇用 主に渡された。[21] 賄賂によって地方官僚が事態を看過し、先住民からの襲撃を恐れたため、政府の介入はほとんどなかった。[21] ゴムブームの終焉は1920年、ゴム価格の暴落と共に訪れた。ゴムブームの終焉と共に、先住民の奴隷化も終息した。 |

| Petroleum operations The year 1978 marked the beginning of petroleum production in Ecuador.[23] Texaco is documented to be the primary international oil company that was given permission to export oil from the coast of Ecuador. This company managed the oil operation from 1971 to 1992.[24] The Ecuadorian government along with Texaco began to scout the Oriente in a joint business known as a consortium.[23] Major shipments of oil were put into action in 1972 after the Trans-Ecuadorian Pipeline was finished. In the years of production business in oil production increased rapidly and Ecuador soon became the second largest producer of oil in South America.[25] Texaco's contract for oil production in Ecuador expired in 1992. PetroEcuador then took over 100% of the oil production management. 1.5 billion barrels of crude oil was reported to have been extracted while under the management of Texaco.[24] There were also reports of 19 billion gallons of waste that had been dumped into the natural environment with the absence of any monitoring or overseeing to prevent damages to the surrounding areas.[24] In addition there was a report of 16.8 million gallons of crude that was dispersed into the environment in relation to spillage out of the Trans-Ecuadorian pipeline.[24] In the early 1990s a lawsuit led by Ecuadorian government officials of 1.5 billion dollars was presented against the Texaco company with claims that there was an immense pollution epidemic that led to the demise of many natural environments as well as an increase in human illnesses.[25] A cancer study was conducted in 1994 by the Centre for Economic and Social Rights which found a rise in health concerns in the Ecuadorian region.[25] it was found that there was a notably higher incidence of cancer in women and men in the countries where there was oil production present for over 20 years.[24] Women also reported increased rates in a copious number of physical ailments such as skin mycosis, sore throat, headaches and gastritis.[24] The primary argument against these findings were that they were weak and biased. Texaco decided on jurisdiction in Ecuador. The case put against Texaco remained in the works for some time. In 2001, Texaco was taken over by Chevron, another oil company, which assumed the liabilities left by the previous production.[25] In February 2011 Chevron was found guilty after inheriting the case left by Texaco and was said to be required to pay 9 billion dollars in damages. This is known to be one of the largest environmental lawsuits award recorded.[26] |

石油事業 1978年はエクアドルにおける石油生産の始まりを画した年である。[23] テキサコ社がエクアドル沿岸からの石油輸出許可を得た主要な国際石油会社であったことが記録されている。同社は1971年から1992年まで石油事業を運 営した。エクアドル政府はテキサコと共同事業体(コンソーシアム)を結成し、オリエンテ地域の探査を開始した。[23] トランエクアドルパイプラインの完成後、1972年に大規模な石油輸送が開始された。生産事業が進むにつれ石油生産量は急増し、エクアドルは間もなく南米 第2位の石油生産国となった。[25] テキサコのエクアドルにおける石油生産契約は1992年に満了した。その後ペトロエクアドルが石油生産管理の100%を引き継いだ。テキサコ管理下で15 億バレルの原油が採掘されたと報告されている。[24] また、周辺地域への被害を防ぐ監視や監督が全く行われないまま、190億ガロンの廃棄物が自然環境に投棄されたとの報告もある。[24] さらに、エクアドル横断パイプラインからの漏出に関連し、1680万ガロンの原油が環境に拡散したとの報告もある。[24] 1990年代初頭、エクアドル政府当局者主導でテキサコ社に対し15億ドルの訴訟が提起された。その主張は、大規模な汚染が蔓延し、多くの自然環境が破壊 されただけでなく、人間の疾病増加も招いたというものだった。[25] 1994年、経済社会権利センターが実施した癌研究では、エクアドル地域における健康問題の増加が確認された[25]。20年以上にわたり石油生産が行わ れてきた地域では、男女ともに癌発生率が著しく高いことが判明した[24]。女性からは皮膚真菌症、咽頭痛、頭痛、胃炎など、数多くの身体的疾患の増加も 報告されている。[24] これらの調査結果に対する主な反論は、その根拠が弱く偏っているというものだった。テキサコ社はエクアドルでの管轄権を主張した。同社に対する訴訟は長期 間にわたり係争状態が続いた。2001年、テキサコは別の石油会社であるシェブロンに買収され、前生産者が残した負債を引き継いだ。[25] 2011年2月、テキサコから引き継いだ訴訟でシェブロンは有罪判決を受け、90億ドルの損害賠償を支払うよう命じられた。これは史上最大級の環境訴訟賠 償金として知られる。[26] |

| Ethnic Wage Gap in Ecuador Ecuador has a history of Spanish colonization of Indigenous people that were enslaved, abused, and exploited.[27] Eventually the country adapted the French Neo-Lamarck ideology leading to "mestizaje". This "mestizaje" began in the 16th century where European colonizers had children with Indigenous people. Ecuador's historical background has left the country with a very stratified social environment.[28] This is the nucleus of the stratification of different social classes in Ecuador. There have been many attempts to reduce such stratification such as making Indigenous languages official in 1998. The Republic of Ecuador also self claimed itself plurinational and intercultural in 2008.[29] It is essential to understand the causes of such racial inequality in a given society in order to be able to approach the problem. Understanding the root of the problems also allows us to understand the existence or lack of public policy initiatives.[28] Structuralist explanations for such inequality is supported by both the minority and dominant groups. Although 19.5% of Ecuadorians believe the economic inequality between the races is due to insufficient work effort from minorities, 47.0% believe it arises from discrimination.[28] Unfortunately, the widest gap of income inequality in the world is in Latin America.[28] The difference in economic division across ethnicities is a consequence of human capital and discrimination.[30] It can be concluded through research that Indigenous people in Ecuador are predisposed to live in poverty and be discriminated against.[30] The percent of Indigenous population in Ecuador that lives in poverty differs by 4.5 times that of the non-Indigenous population.[30] Education is one of the greatest factors for such economical inequality in the country. The lack of education for many Indigenous people makes it difficult for the ethnic group to overcome such poverty. Unfortunately, the probability of Indigenous people to stay in school is very low. It is evident that there is an existing difference in education between the ethnic groups.[31] The Indigenous population only has an average of 4.5 years of formal education, while non-Indigenous population's average of years is 8.[30] The minority group has a net secondary school enrollment rate of 14.0% and because of rural residence and work they have a much lower probability of staying in school.[30] There is also a drastic social impact on Indigenous people mainly through exclusion. This racism raised the use of certain terminology such as "cholo" and "longo" which are threatening because they are not institutionalized to any official ethnic group. With such unhistorical and unstructured rise to the terminology, the terminology is more flexible when used and persistent.[29] The paternalistic system of ethnic discrimination transitioned to a more democratization of racial relations. Although there are no more "haciendas" (working systems where Indigenous peoples were exploited for labor) and Amerindians now have a right to vote, there is still an everyday discriminatory challenge. Amerindians often feel vulnerable and predisposed to physical and verbal attacks, which cause them to be more reserved and avoid contact with whites. An Indigenous witness claimed he was told to leave a restaurant because "no Indians [were] admitted to [that] locale".[32] Racism can be seen such as travelling in public transportation, interactions in public spaces, and the yearning to be white from Amerindians.[32] |

エクアドルにおける民族間の賃金格差 エクアドルには、先住民が奴隷化され虐待・搾取されたスペイン植民地時代の歴史がある[27]。やがて同国はフランスの新ラマルク主義思想を取り入れ、 「混血化」が進んだ。この「混血化」は16世紀に始まり、ヨーロッパの植民者が先住民と子をもうけた。エクアドルの歴史的背景は、極めて階層化された社会 環境を同国に残した。 [28] これがエクアドルにおける様々な社会階級の分断の根源である。1998年に先住民言語を公用語とするなど、こうした分断を解消する試みは数多く行われてき た。エクアドル共和国は2008年には自らを多民族国家かつ異文化共生国家と宣言した。[29] 問題に取り組むためには、特定の社会における人種的不平等の原因を理解することが不可欠である。問題の根源を理解することは、公共政策の取り組みの有無を 把握することにも繋がる。[28] このような不平等に対する構造主義的説明は、少数派グループと支配的グループ双方の支持を得ている。エクアドル人の19.5%が人種間の経済的不平等は少 数派の労働意欲不足に起因すると考える一方、47.0%は差別が原因だと信じている。[28] 残念ながら、世界で最も深刻な所得格差はラテンアメリカに存在する。[28] 人種間の経済的分断の差は、人的資本と差別の結果である。[30] 研究から、エクアドルの先住民は貧困状態に置かれ、差別を受ける傾向にあると結論づけられる。[30] エクアドルにおける貧困層の先住民人口比率は、非先住民人口の4.5倍に達する。[30] 教育は国内のこうした経済的不平等の最大の要因の一つだ。多くの先住民が教育を受けられないため、この民族集団が貧困を克服するのは困難である。残念なが ら、先住民が学校に留まる確率は極めて低い。民族集団間の教育格差が存在する事実は明らかだ。[31] 先住民の平均就学年数はわずか4.5年であるのに対し、非先住民の平均就学年数は8年である。[30] 少数派集団の中等教育純就学率は14.0%に過ぎず、農村居住や就労のため、学校に留まる可能性はさらに低い。[30] 先住民には主に排除を通じて深刻な社会的影響も生じている。この人種差別は「チョロ」や「ロンゴ」といった特定の用語の使用を増加させた。これらは公式な 民族集団に制度化されていないため脅威となる。こうした歴史的根拠や構造を持たない用語の出現により、その使用はより柔軟で持続的である。[29] 民族差別を伴う父権主義的体制は、人種関係の民主化へと移行した。もはや「ハシエンダ」(先住民が労働力として搾取された制度)は存在せず、アメリカ先住 民は投票権を獲得したが、日常的な差別的課題は依然として存在する。先住民はしばしば脆弱さを感じ、身体的・言語的攻撃を受けやすい立場にある。そのため 彼らはより控えめになり、白人との接触を避ける傾向がある。ある先住民の証言によれば、彼は「この店にはインディアンは入店禁止だ」と言われ、レストラン から追い出されたという。[32] 人種差別は公共交通機関の利用、公共空間での交流、そして先住民による白人への憧れといった形で現れている。[32] |

| Mining Conflicts Over the last 30 years various Indigenous groups have faced land and extractivism conflicts due to foreign and domestic mining interests. In 2010 a Chinese mining consortium called CRCC-Tongguan acquired a Canadian mining firm called Corriente resources which owned some of Ecuador's largest copper mines through its subsidiaries EcuaCorriente SA and Explocobres SA.[33] According to researchers for the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, Cintia Quiliconi and Pablo Rodriquez Vasco, their goal was as such: to "[diversify] their supply of metals while reducing the monopoly power of Western multinational companies such as Broken Hill Proprietary (BHP, formerly known as BHP Billiton), the International Minerals Corporation, Rio Tinto, Vale, Anglo American, and others."[33] Gaining control of these mines would allow the consortium to achieve its goals of dominating the world market and expanding its metal supplies. The consortium was owned and operated by two companies owned and regulated by the Chinese government, the Tongling Nonferrous Metals Group and the China Railway Construction Corporation.[33] The subsidiaries of Corriente resources each own one of Ecuador's two biggest copper mining concessions respectively. EcuaCorriente SA owns the Mirador concession, a 10,000 hectare plot of land located in the Zamora Chinchipe province. The Mirador mine began operating in 2019 initially producing about 10,000 tons of copper a day.[33] The San Carlos Panantza concession which is owned by Explocobres SA is a 28,548 hectare plot of land located in the Morona Santiago province in the Arutam region. Both of these concessions are located on the ancestral lands of the indigenous Ecuadorian peoples known as the Shuar. The ancestral lands of the Shuar stretch along the Cordillera del Cóndor, a mountain range that stretches along the southeastern border of Ecuador and Peru and into the Amazon rainforest. Of the 900,688 hectares of land that are ancestral to the Shuar, only 718,220 are recognized by the Ecuadorian government.[33] The Mirador project located in the town of Tundayme was targeted by the consortium because of the town's diverse ethnic make-up.[33] The town had 737 residents with only 147 of whom identifying as Shuar, meaning that the consortium would face far less local opposition from Indigenous people to their operations. The acquisition of the Mirador concession by Corriente Resources began well before the purchase of the company by CRCC-Tongguan. Corriente resources struck informal deals with local leaders directly bypassing the Ecuadorian state, taking advantage of its lack of oversight of rural areas. These practices are illegal in Ecuador and as Quiliconi and Vasco explain, they served to fragment local communities by striking deals with specific local leaders creating opposition in the wider community.[33] These practices were later continued following CRCC-Tongguan's acquisition of Corriente Resources. Using these practices Corriente was able to strike deals with the non indigenous inhabitants of Tundayme who were far less concerned with the intrinsic natural value of the land than its Shuar residents. For the residents of Tundayme that would not sell their land, the consortium turned to far more aggressive tactics. According to Quiliconi and Vasco, "EcuaCorriente SA, unlike its Canadian predecessor, also leveraged the full support of the Ecuadorian state, which ordered the displacement of these locals by deploying security forces while citing Ecuador's laws on public safety."[33] When the consortium's manipulation tactics failed they turned to aggressive force, strong-arming the state to push its residents off of their land, even going as far as to destroy a local school and church in 2014.[33] Also in 2014 a local Shuar leader, José tendetza wrote a letter to CRCC-Tongguan criticizing their operations. Following this letter, Tendetza received multiple threats culminating in his torture and murder, a crime which has yet to be investigated.[33] In 2018 a group called the Amazon Community of Social Action in Cordillera del Condor) sued the consortium in Ecuador's lower courts, arguing that the mining operations were taking place of the ancestral lands of the Shuar people but the case was thrown out. CASCOMI is currently trying to sue the consortium in Ecuador's higher courts.[34] The San Carlos Panantza concession is located in the Arutam region. Unlike Mirador in Tundayme, Arutam is inhabited predominantly by Shuar peoples which made the consortiums divide and conquer tactics far less effective. Due to far larger and more united opposition, the consortium through Explocobres SA used even more aggressive tactics than those used in Mirador but to a far greater extent. In 2016 Explocobres SA began an operation involving over 2000 Ecuadorian police and military to forcibly evict residents of the San Juan Bosco canton.[33] These tactics instilled fear into the inhabitants of the surrounding areas as well. The residents of the town of Nankints were told they had to evacuate or face similar force. When they tried to return to their homes, over 41 residents were arrested on "terrorism" charges. When other residents tried to return they faced military opposition including tanks and helicopters, resulting in multiple deaths and many injuries. Due to these widely disproportionate uses of force which made international news coverage, CASCOMI was able to seek relief with the Ecuadorian courts. In 2022, Ecuador's high court revoked mining rights to the San Carlos-Panantza concession.[33] |

鉱業紛争 過去30年間、様々な先住民族グループが国内外の鉱業利権により土地と資源開発をめぐる紛争に直面してきた。2010年には中国の鉱業コンソーシアムであ るCRCC-Tongguanが、子会社のEcuaCorriente SAとExplocobres SAを通じてエクアドル最大の銅鉱山を所有するカナダの鉱業会社Corriente resourcesを買収した。[33] カーネギー国際平和財団の研究者シンティア・キリコーニとパブロ・ロドリゲス・バスコによれば、その目的は「金属供給源の多様化を図りつつ、ブロークンヒ ル・プロプライエタリ(BHP、旧BHPビリトン)、インターナショナル・ミネラルズ・コーポレーション、リオ・ティント、ヴァーレ、アングロ・アメリカ ンなどの欧米多国籍企業の独占力を弱めること」にあった。[33] これらの鉱山を掌握することで、コンソーシアムは世界市場を支配し金属供給を拡大するという目標を達成できる。コンソーシアムは中国政府が所有・規制する 2社、銅陵有色金属集団と中国鉄建集団によって所有・運営されていた。[33] コリエンテ・リソーシズの子会社は、それぞれエクアドルの二大銅鉱区権益を所有している。エクアコリエンテ社はミラドール鉱区権益を所有しており、これは サモラ・チンチペ県に位置する1万ヘクタールの土地である。ミラドール鉱山は2019年に操業を開始し、当初は1日あたり約1万トンの銅を生産した。 [33] エクスプロコブレスSAが所有するサンカルロス・パナンツァ鉱区は、アルタム地域モロナ・サンティアゴ県に位置する28,548ヘクタールの土地である。 これらの鉱区はいずれも、シュアル族として知られるエクアドル先住民の祖先伝来の土地に位置している。シュアル族の祖先伝来の土地は、エクアドルとペルー の南東国境に沿って伸び、アマゾン熱帯雨林へと続く山脈、コンドル山脈に沿って広がっている。シュアル族の祖先伝来の土地900,688ヘクタールのう ち、エクアドル政府が認めているのは718,220ヘクタールのみである。[33] タンダイメ町に位置するミラドール・プロジェクトは、同町の多様な民族構成ゆえにコンソーシアムの標的となった[33]。町の人口737人のうちシュアル 族と自認する者はわずか147人であり、コンソーシアムは事業に対する先住民からの現地反対を大幅に回避できる見込みだった。ミラドール鉱区の取得は、 CRCC-トンクアンによるコリエンテ・リソーシズ買収よりかなり前に行われた。同社はエクアドル政府の地方監視体制の弱さを利用し、地方指導者と直接非 公式な取引を結んだ。こうした手法はエクアドルでは違法であり、キリコニとバスコが指摘するように、特定指導者との取引によって地域社会を分断し、広範な コミュニティに反対勢力を生み出す結果となった。[33] こうした手法は、CRCC-TongguanによるCorriente Resources買収後も継続された。この手法を用いることで、Corrienteはトゥンダイメの非先住民住民との契約を成立させることができた。彼 らはシュアル族住民に比べて、土地の自然的価値そのものへの関心がはるかに低かったのだ。 土地を売却しないトゥンダイメ住民に対しては、コンソーシアムははるかに攻撃的な戦術に転じた。キリコニとバスコによれば、「エクアコリエンテ社はカナダ の先代企業とは異なり、エクアドル国家の全面的な支援も利用した。国家は公共の安全に関する国内法を根拠に治安部隊を動員し、住民の強制退去を命じたので ある」[33]。コンソーシアムの操作戦術が失敗すると、彼らは強硬手段に打って出た。国家を恫喝して住民を土地から追い出し、2014年には地元の学校 と教会を破壊するに至った[33]。同じく2014年、地元のシュアル族指導者ホセ・テンデツァはCRCC-トンクワン社に書簡を送り、彼らの事業運営を 批判した。この書簡の後、テンデツァは複数の脅迫を受け、最終的に拷問と殺害に至った。この犯罪は未だに捜査されていない。[33] 2018年、アマゾン社会行動共同体(コルドイラ・デル・コンドル)と名乗る団体が、鉱業活動がシュアル族の祖先の土地で行われていると主張し、コンソー シアムをエクアドルの下級裁判所に提訴したが、この訴訟は却下された。CASCOMIは現在、エクアドル高等裁判所において同コンソーシアムを提訴しよう としている。[34] サン・カルロス・パナンツァ鉱区はアルタム地域に位置する。トゥンダイメのミラドールとは異なり、アルタムには主にシュアル族が居住しており、コンソーシ アムの分断統治戦術ははるかに効果を失った。はるかに大規模で結束した反対運動に直面したため、コンソーシアムはエクスプロコブレス社を通じてミラドール 鉱山で用いた手法よりもさらに過激な戦術を、より広範に展開した。2016年、エクスプロコブレス社はサン・フアン・ボスコ郡の住民を強制退去させるた め、2000人以上のエクアドル警察・軍隊を動員した作戦を開始した[33]。この戦術は周辺地域の住民にも恐怖を植え付けた。ナンキントスの町民は、避 難しなければ同様の武力行使に直面すると通告された。彼らが自宅に戻ろうとした際、41人以上の住民が「テロリズム」容疑で逮捕された。他の住民が帰還を 試みると、戦車やヘリコプターを含む軍隊の抵抗に遭い、複数の死者や多数の負傷者が出た。こうした国際的な報道を呼んだ著しく不均衡な武力行使により、 CASCOMIはエクアドルの裁判所に救済を求めることができた。2022年、エクアドル最高裁はサンカルロス・パナンツァ鉱区への採掘権を無効とした。 |

| Politics In 1986, Indigenous people formed a national political organization,[35]: xv the Confederation of Indigenous Nationalities of Ecuador (CONAIE), which has been the primary political organization ever since. The CONAIE has been influential in national politics, including the ouster of the presidents Abdalá Bucaram in 1997 and Jamil Mahuad in 2000. In 1998, Ecuador signed and ratified the current international law concerning Indigenous peoples, Indigenous and Tribal Peoples Convention, 1989.[36] It was adopted in 1989 as the International Labour Organization Convention 169. |

政治 1986年、先住民は全国的な政治組織を結成した[35]: xv 。それがエクアドル先住民民族連合(CONAIE)であり、以来主要な政治組織となっている。CONAIEは国家政治において影響力を持ち、1997年のアブダラ・ブカラム大統領と2000年のハミル・マウアド大統領の退陣に関与した。 1998年、エクアドルは先住民族に関する現行の国際法である「先住民族及び部族民に関する条約(1989年)」に署名し批准した[36]。これは1989年に国際労働機関(ILO)第169号条約として採択されたものである。 |

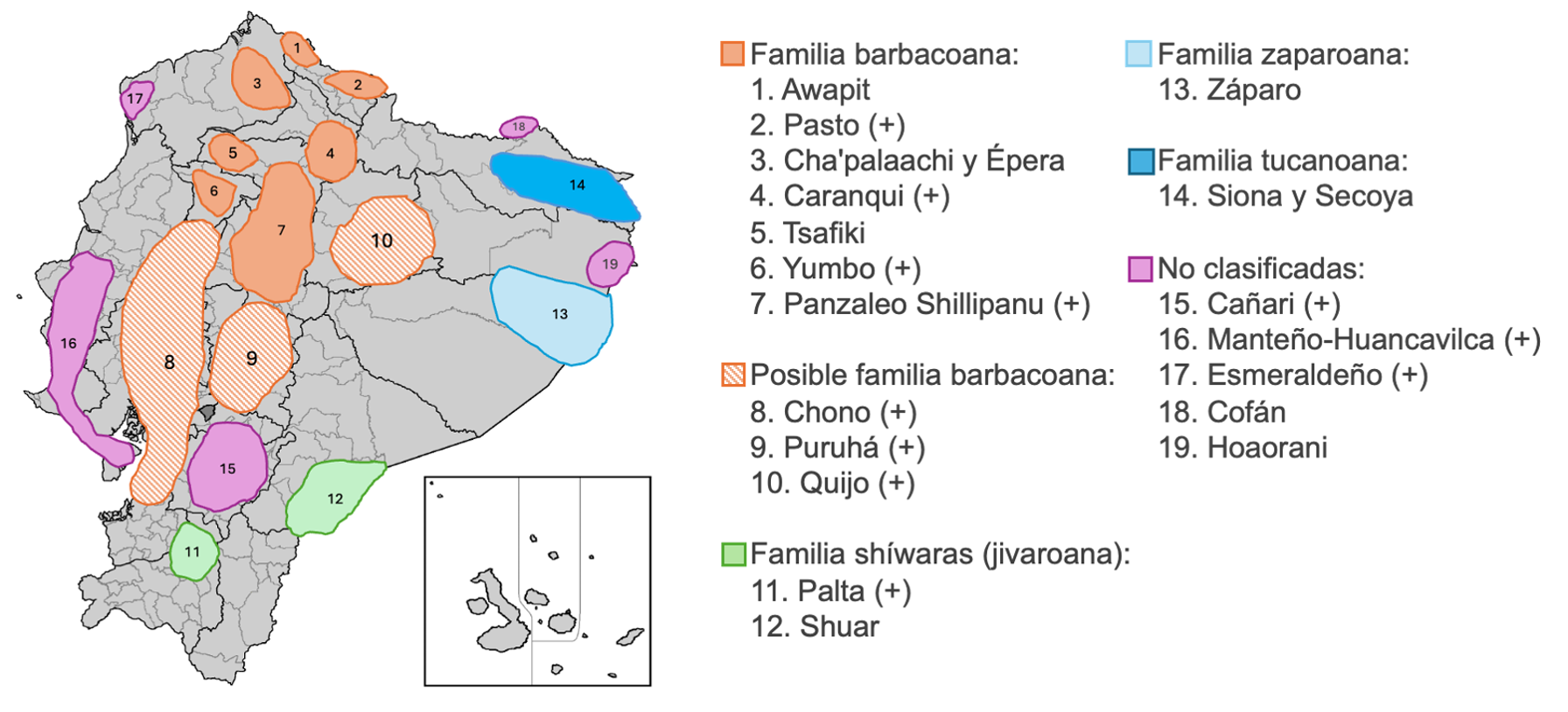

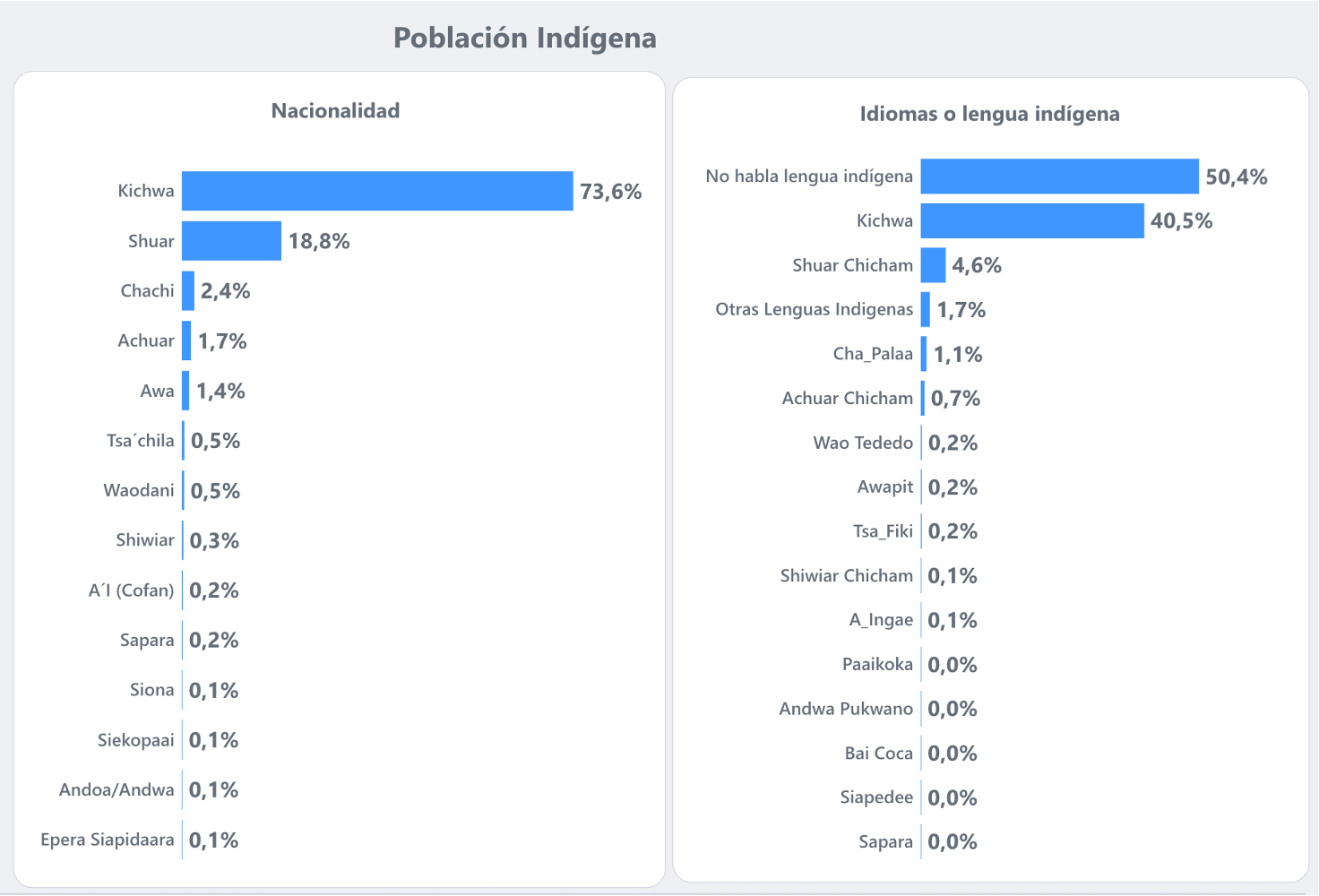

| Demographics and language Demographics  Distribution of indigenous "nationalities" and proportion of the indigenous population (circa 1'302.057 people or 7.7% of the total) that speaks an indigenous language. Ethnographic estimations have been carried out based on censuses throughout Ecuador's history. The first recorded census was in 1778, when Ecuador was then the Royal Audience of Quito. This took place during the presidency of Juan José de Villalengua, and it was estimated that out of a total population of about 439,000 people, 63% of the population was Indigenous, 26% white, and the remaining 11% were "castas," meaning various mixtures of Indigenous people, whites, and Afro-descendants.[37] The next census was conducted during the republican era by Vicente Ramón Roca and José María Urbina. It counted a total of 869,892 people, of whom 49% were Amerindians, 40% were white, 10% were mulatto, and 1% were black. This census is of great importance as it allows for the study of the period of population transition experienced in Ecuador from 1846 after the Marcist Revolution to 1889 at the beginning of the Liberal Revolution.[38] The subsequent census that included an ethnographic estimation was in 1950, during the government of Galo Plaza Lasso. It determined that the total population was about 2,551,540 Ecuadorians. Based on an estimation by language, 11.12% were Indigenous people who spoke Kichwa, a product of a mestizaje process, while Spanish in 1950 was the predominant language nationally, spoken as a mother tongue by about 88.4% of the population. In that same context, a high illiteracy rate (36.1%) was recorded.[39] From 2001 onwards, censuses were conducted using self-identification criteria, meaning that during data collection, respondents were asked to identify with an ethnic group. In that year, approximately 12 million Ecuadorians were counted, of whom 77.4% self-identified as mestizo, 6.8% as Indigenous, 5% as Afro-Ecuadorian, and 10.5% as white. Starting in 2010, Montuvios began to be included in this group; while genetically mestizo, they were considered an ethnic category and recognized as a distinct culture. In the latest Population and Housing Census of 2022, the majority of the population self-identified, according to their culture and customs, as mestizo (77.5%), followed by those who considered themselves Montuvios (7.7%), Indigenous (7.7%), Afro-Ecuadorians (4.8%), and white (2.2%).[40] |

人口統計と言語 人口統計  先住民「民族」の分布と、先住民言語を話す先住民人口(約1,302,057人、総人口の7.7%)の割合。 エクアドルの歴史を通じて実施された国勢調査に基づき、民族学的推定が行われてきた。最初の記録された国勢調査は1778年、当時のエクアドルがキト王室 裁判所であった時期である。これはフアン・ホセ・デ・ビジャレンガ大統領の時代に実施され、総人口約43万9千人のうち、63%が先住民、26%が白人、 残り11%が「カスタ」(先住民・白人・アフリカ系混血の様々な混合)と推定された。[37] 次の国勢調査は共和制時代にビセンテ・ラモン・ロカとホセ・マリア・ウルビナによって実施された。総人口869,892人のうち、49%がアメリカ先住 民、40%が白人、10%がムラート(混血)、1%が黒人であった。この国勢調査は、マルキスト革命後の1846年からリベラル革命が始まった1889年 にかけてエクアドルが経験した人口移行期を研究できる点で非常に重要だ。[38] 民族学的推定を含む次の国勢調査は、ガロ・プラザ・ラッソ政権下の1950年に行われた。この調査では総人口が約2,551,540人のエクアドル人であ ると確定された。言語に基づく推定では、11.12%がメスティーソ化過程の産物であるキチュワ語を話す先住民であった。一方、1950年時点でスペイン 語は全国的に支配的な言語であり、人口の約88.4%が母語として話していた。また、当時の識字率は36.1%と低い水準であった[39]。 2001年以降の国勢調査では自己申告方式が採用され、回答者は調査時に自らの民族的帰属を表明することとなった。この年、約1200万人のエクアドル人 が計上され、そのうち77.4%がメスティソ、6.8%が先住民、5%がアフリカ系エクアドル人、10.5%が白人と自己申告した。2010年以降、モン トゥビオスがこのグループに含まれるようになった。彼らは遺伝的にはメスティソであるが、民族カテゴリーとして扱われ、独自の文化を持つ集団として認めら れたのである。2022年の最新国勢調査では、文化と習慣に基づき、人口の大多数が自身をメスティーソ(77.5%)と認識した。次いでモントゥビオス (7.7%)、先住民(7.7%)、アフリカ系エクアドル人(4.8%)、白人(2.2%)が続いた。[40] |

| Language According to the last Census of 2022, of the 7.7% of the population that identifies as indigenous, 3.2% speak an indigenous language.[41][42] From a total indigenous population of 1'302.057 people, 50,4% of them do not speak an indigenous language, the majority of them belonging however to the kichwa nationality. In absolute numbers, that 3.2% of the population amounts to 645.821 people that speak an indigenous language.[41] The distribution is the following: Kichwa with 527,333 speakers, making up 40.5% of the total indigenous population. Shuar with 59,894 speakers, making up 4.6% of the total indigenous population. Other languages with 58,594 speakers, making up 4.5% of the total indigenous population. The other languages spoken in Ecuador include Awapit (spoken by the Awá), A'ingae (spoken by the Cofan), Achuar Chicham (spoken by the Achuar), Shiwiar (spoken by the Shiwiar), Cha'palaachi (spoken by the Chachi), Tsa'fiki (spoken by the Tsáchila), Paicoca (spoken by the Siona and Secoya), and Wao Tededeo (spoken by the Waorani). |

言語 2022年の国勢調査によれば、先住民と自認する人口の7.7%のうち、3.2%が先住民言語を話す。[41][42] 先住民人口1,302,057人のうち、50.4%は先住民言語を話さない。ただしその大半はキチュワ民族に属している。絶対数では、この3.2%の人口 は先住民言語を話す645,821人に相当する。[41] その分布は以下の通りだ: キチュワ語:話者数527,333人。先住民人口全体の40.5%を占める。 シュアル語:話者数59,894人。先住民人口全体の4.6%を占める。 その他の言語は58,594人(先住民総人口の4.5%)である。 エクアドルで話されるその他の言語には、アワ族が話すアワピト語、コファン族が話すアインゲ語、アチュアル族が話すアチュアル・チチャム語、シウィアル族 が話すシウィアル語、チャチ族が話すチャパラチ語、 ツァフィキ語(ツァチラ族)、パイコカ語(シオナ族とセコヤ族)、ワオ・テデデオ語(ワオラニ族)などがある。 |

| Dolores Cacuango, Ecuadorian Indigenous rights activist |

ドロレス・カクアンゴ、エクアドル先住民権利活動家 |

| References 1. "Ecuador: Censo de Población y Vivienda 2022" (PDF). censoecuador.gob.ec. 21 September 2023. Retrieved 22 May 2024. 2. Salazar, Ernesto (1996). "Les premiers habitants de l'Equateur". Les Dossiers d'Archéologie (in French). 214. Dijon: Faton: 3–85. 3. Encyclopedia of the World's Minorities (2013), p. 422. Edited by Carl Skutsch 4. Zambrano, Ana Karina; Gaviria, Aníbal; Cobos-Navarrete, Santiago; Gruezo, Carmen; Rodríguez-Pollit, Cristina; Armendáriz-Castillo, Isaac; García-Cárdenas, Jennyfer M.; Guerrero, Santiago; López-Cortés, Andrés; Leone, Paola E.; Pérez-Villa, Andy; Guevara-Ramírez, Patricia; Yumiceba, Verónica; Fiallos, Gisella; Vela, Margarita; Paz-y-Miño, César (2019). "The three-hybrid genetic composition of an Ecuadorian population using AIMs-InDels compared with autosomes, mitochondrial DNA and y chromosome data". Scientific Reports. 9 (1): 9247. Bibcode:2019NatSR...9.9247Z. doi:10.1038/s41598-019-45723-w. PMC 6592923. PMID 31239502. 5. Willey, Gordon R.; Philip Phillips (2001) [1958]. R. Lee Lyman (ed.). Method and theory in American archaeology. Classics in Southeastern Archaeology. Michael J. O'Brien (second ed.). Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press. pp. 104–139. ISBN 0-8173-1088-6. 6. Marcos, Jorge G. (2003). "A Reassessment of the Ecuadorian Formative" (PDF). In J. Scott Raymond (ed.). Archaeology of Formative Ecuador. Richard L. Burger. Washington, D.C.: Dumbarton Oaks, Trustees for Harvard University. ISBN 0-88402-292-7. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-02-11. Retrieved 2008-07-18. The initial cultivation of corn probably took place around 6000 B.C.1 on the Santa Elena peninsula and at around 4300 B.C.2 at Lake Ayauchi in the southeastern Oriente of Ecuador (Pearsall 1995: 127–128; Piperno 1988: 203–224, 1990, 1995). 7. Peregrine, Peter. Outline of Archaeological Traditions. New Haven: Human Relations Area Files. 8. "Integration Period". The Concise Oxford Dictionary of Archaeology. Oxford University Press. 2003. 9. Stothert, Karen E.; Dolores R. Piperno; Thomas C. Andres (2003). "Terminal Pleistocene/Early Holocene human adaptation in coastal Ecuador: the Las Vegas evidence" (PDF). Quaternary International. 109–110 (South America: Long and Winding Roads for the First Americans at the Pleistocene/Holocene Transition). San Antonio, Texas, USA: Center for Archaeological Research, The University of Texas at San Antonio: 23–43. Bibcode:2003QuInt.109...23S. doi:10.1016/S1040-6182(02)00200-8.[permanent dead link] 10. Salazar, Ernesto (2003). "Los primeros habitantes del Ecuador I: Los primeros habitantes del Ecuador-2". La Hora (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 2008-05-01. Retrieved 2008-07-14. Puntas de lanza de varios tamaños han sido encontradas en diferentes lugares del país, particularmente, en las provincias del Carchi, Imbabura, Pichincha, Cotopaxi, Azuay y Loja. 11. Salazar, Ernesto (2003). "Los primeros habitantes del Ecuador I: Los primeros habitantes-1". La Hora (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 2008-05-01. Retrieved 2008-07-14. Los seres humanos parecen haber ocupado rápidamente el callejón interandino. La Costa, en cambio habría permanecido largamente deshabitada, a juzgar por la relativa escasez de asentamiento precerámicos descubiertos (excepto los numerosos sitios de la península de Santa Elena) en una región que, comparativamente, es una de las más estudiadas del país. 12. Lynch, Thomas F. (2000). "Earliest South American Lifeways". In Frank Salomon (ed.). South America. The Cambridge History of the Native Peoples of the Americas. Vol. III. Stuart B. Schwartz (third ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-63075-4. In fact, this region somewhat resembles the African highland zone, in which our species evolved, so it is no wonder it was swiftly and solidly colonized. 13. Rostoker, Arthur (2003). "Formative Period Chronology for Eastern Ecuador" (PDF). In J. Scott Raymond (ed.). Archaeology of Formative Ecuador. Richard L. Burger. Washington, D.C.: Dumbarton Oaks, Trustees for Harvard University. p. 541. ISBN 0-88402-292-7. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-02-11. Retrieved 2008-07-18. Preceramic and aceramic settlements, as well as later pottery-using societies, likely were already established at some places in the Oriente well before 500 B.C. 14. Lippi, Ronald D. (1996). La Primera Revolución Ecuatoriana: El desarrollo de la Vida Agrícola en el Antiguo Ecuador. Quito: Instituto de historia y antropología andinas. 15. Erickson, Clark (2000). "Lomas de ocupación en los Llanos de Moxos" (PDF). Arqueología de las Tierras Bajas. Montevideo: 207–226. Retrieved 2008-07-18. 16. Roosevelt, Anna C. (2000). "Maritime, Highland, Forest Dynamic". South America. The Cambridge History of the Native Peoples of the Americas. Vol. III (third ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 264–349 [344]. ISBN 0-521-63075-4. Similarly, cultural elaboration does not turn out to have been linked to social organization as predicted by earlier theories. Elaboration in the form of art and technology and monument building was found in both areas, without evidence of centralized, controlling administrations. 17. Shimada, Izumi (2000). "Evolution of Andean Diversity: Regional Formations (500 B.C.E-C.E. 600)". In Frank Salomon (ed.). South America. The Cambridge History of the Native Peoples of the Americas. Vol. III. Stuart B. Schwartz (third ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-63075-4. 18. Rudolph, James D. (1991). Ecuador: A Country Study. Library of Congress Country Studies. Washington, D.C.: Library of Congress. LCCN 91009494. 19. José Luis Espinoza E., Tomebamba, Pumapungo, Hatun Cañar Arqueología Ecuatoriana 2010 20. Juillard, Gaëtan. "Arqueología Ecuatoriana | Revistas | Si Quieren Ser Inkas… Que Sean Felices". Arqueología Ecuatoriana. 21. Ingrid Fernandez, The Upper Amazonian Rubber Boom and Indigenous Rights 1900-1925 Archived 2014-06-05 at the Wayback Machine Florida Gulf Coast University 22. Ruiz, Jean L. (May 2006). Civilized People in Uncivilized Places: Rubber, Race, and Civilization during the Amazonian Rubber Boom (PDF) (MoA thesis). University of Saskatchewan. Archived from the original (PDF) on 14 June 2013. 23. Background on Texaco Petroleum Company's Former Operations in Ecuador Archived August 16, 2011, at the Wayback Machine 24. "Epidemiology vs epidemiology: The case of oil exploitation in the Amazon basin of Ecuador". ije.oxfordjournals.org. Archived from the original on 17 July 2012. Retrieved 2 February 2022. 25. Carly Gillis, Ecuador Vs. Chevron-Tesaco: A Brief History April 27, 2011 26. SIMON ROMERO and CLIFFORD KRAUSS, Ecuador Judge Orders Chevron to Pay $9 Billion NYTimesFebruary 14, 2011 27. Oviedo Oviedo, Alexis (2023-05-31). "Ecuador: Racism and Ethnic Discrimination in the ups and downs of Public Policy (Ecuador: racismo y discriminación étnica en el vaivén de la política pública)". Mundos Plurales - Revista Latinoamericana de Políticas y Acción Pública. 9 (2): 111–133. doi:10.17141/mundosplurales.2.2022.5483. hdl:10644/9193. ISSN 2661-9075. 28. Telles, Edward (May 2013). "Understanding Latin American Beliefs about Racial Inequality". American Journal of Sociology. 118 (6): 1559–1595. doi:10.1086/670268. S2CID 39970967. 29. Roitman, Karem (December 2017). "Mestizo Racism in Ecuador". Ethnic & Racial Studies. 40 (15): 2768–2786. doi:10.1080/01419870.2016.1260749. S2CID 152231395. 30. García-Aracil, Adela (2006). "Gender and Ethnicity Differentials in School Attainment and Labor Market Earnings in Ecuador". World Development. 34 (2): 289–307. doi:10.1016/j.worlddev.2005.10.001. hdl:10261/103884. 31. Antón Sánchez, Jhon. "Remarks on on Racial and Ethnic Inequalities in the Struggle for Social and Environmental Justice | Initiative on Race, Gender and Globalization". irgg.yale.edu. Retrieved 2023-09-05. 32. de la Torre, Carlos (January 1999). "Everyday Forms of Racism in Contemporary Ecuador: The Experiences of the Middle-Class Indians". Ethnic & Racial Studies. 22: 92–112. doi:10.1080/014198799329602. 33. "Chinese Mining and Indigenous Resistance in Ecuador". Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. Retrieved 2025-03-18. 34. "Executive Summary | UNDERMINING RIGHTS". {{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires |journal= (help) 35. Gerlach, Allen. Indians, Oil and Politics: A Recent History of Ecuador. SR Books, Wilmington Delaware. 2003 36. NORMLEX International Labour Organization (ILO) 37. "Una mirada histórica a la estadística del Ecuador". Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Censos: 16. 2015. 38. Grijalva, Manuel Miño (2022-08-01). "La población del Ecuador en la transición, 1846–1889". Boletín Academia Nacional de Historia (in Spanish). 100 (207): 95. ISSN 2773-7381. Retrieved 2025-05-31. 39. Una mirada histórica a la estadística del Ecuador. 2015. p. 55. Retrieved 22 July 2025. 40. "Censo de Población y Vivienda 2022". 21 September 2023. Retrieved 21 September 2023. 41. "Censo de Población y Vivienda de Ecuador". INEC. 2022–2023. Retrieved 30 June 2025. 42. "Constitución Política de la República del Ecuador". Archived from the original on October 17, 2015. Retrieved September 13, 2014. |

参考文献 1. 「エクアドル:2022年人口・住宅センサス」 (PDF). censoecuador.gob.ec. 2023年9月21日. 2024年5月22日閲覧。 2. サラザール、エルネスト (1996). 「エクアドルの最初の住民」. 『考古学資料』 (フランス語). 214. ディジョン: ファトン: 3–85. 3. 『世界の少数民族事典』 (2013), p. 422. カール・スクッチ編 4. ザンブラノ, アナ・カリーナ; ガビリア, アニバル; コボス=ナバレテ、サンティアゴ;グルエソ、カルメン;ロドリゲス=ポリット、クリスティーナ;アルメンダリス=カスティーヨ、アイザック;ガルシア=カ ルデナス、ジェニーファー・M.;ゲレーロ、サンティアゴ;ロペス=コルテス、アンドレス;レオーネ、パオラ・E.;ペレス=ビジャ、アンディ;ゲバラ= ラミレス、パトリシア;ユミセバ、ベロニカ;フィアロス、ギセラ;ベラ、マルガリータ; パズ=イ=ミーニョ、セサル(2019)。「AIMs-InDelsを用いたエクアドル人集団の三系統遺伝的構成:常染色体、ミトコンドリアDNA、Y染 色体データとの比較」。Scientific Reports。9 (1): 9247。Bibcode:2019NatSR...9.9247Z。doi:10.1038/s41598-019-45723-w. PMC 6592923. PMID 31239502. 5. ウィリー、ゴードン・R.;フィリップ・フィリップス(2001年)[1958年]。R. リー・ライマン(編)。『アメリカ考古学の方法と理論』。南東部考古学の古典。マイケル・J・オブライエン(第2版)。タスカルーサ:アラバマ大学出版 局。pp. 104–139。ISBN 0-8173-1088-6。 6. マルコス、ホルヘ・G. (2003). 「エクアドル形成期の再評価」 (PDF)。J. Scott Raymond(編)『エクアドル形成期の考古学』所収。Richard L. Burger。ワシントンD.C.:ダンバートン・オークス、ハーバード大学評議員会。ISBN 0-88402-292-7。2012年2月11日にオリジナル(PDF)からアーカイブ。2008年7月18日に取得。トウモロコシの最初の栽培はおそ らく紀元前6000年頃1にサンタエレナ半島で、紀元前4300年頃2にはエクアドル南東部オリエンテ地方のアヤウチ湖で始まった(Pearsall 1995: 127–128; Piperno 1988: 203–224, 1990, 1995)。 7. ペレグリン、ピーター。『考古学的伝統の概要』。ニューヘイブン:ヒューマン・リレーションズ・エリア・ファイルズ。 8. 「統合期」。『オックスフォード考古学辞典(コンサイス版)』。オックスフォード大学出版局。2003年。 9. ストーサート、カレン・E.;ドロレス・R. パイパーノ;トーマス・C. アンドレス(2003)。「エクアドル沿岸部における最終更新世/初期完新世の人類適応:ラス・ベガス遺跡の証拠」 (PDF). Quaternary International. 109–110 (南アメリカ:更新世/完新世移行期における最初のアメリカ人たちの長く曲がりくねった道). サンアントニオ、テキサス州、アメリカ合衆国:テキサス大学サンアントニオ校考古学研究センター: 23–43. Bibcode:2003QuInt.109...23S. doi:10.1016/S1040-6182(02)00200-8.[永久リンク切れ] 10. サラザール、エルネスト(2003年)。「エクアドルの最初の住民 I:エクアドルの最初の住民-2」。ラ・オラ(スペイン語)。2008年5月1日にオリジナルからアーカイブ。2008年7月14日に取得。様々なサイズ の槍先が国内の様々な場所で発見されている。特にカルチ、インバブラ、ピチンチャ、コトパクシ、アズアイ、ロハの各州で発見されている。 11. Salazar, Ernesto (2003). 「エクアドルの最初の住民 I: 最初の住民-1」. La Hora (スペイン語). 2008年5月1日にオリジナルからアーカイブ。2008年7月14日に取得。人間はアンデス山脈の谷間を急速に占拠したようだ。一方、海岸地域は、比較 的、国内で最も研究が進んでいる地域であるにもかかわらず、発見された先陶器時代の集落が比較的少ない(サンタエレナ半島にある数多くの遺跡を除く)こと から判断すると、長い間、無人であったと思われる。 12. リンチ、トーマス F. (2000). 「南米最古の生活様式」. フランク・サロモン(編)。南アメリカ。ケンブリッジ・アメリカ大陸先住民史。第 III 巻。スチュワート・B・シュワルツ(第 3 版)。ケンブリッジ:ケンブリッジ大学出版局。ISBN 0-521-63075-4。実際、この地域は、私たち人類が進化したアフリカの高地帯に多少似ているため、迅速かつ確実に植民地化されたのも不思議では ない。 13. ロストカー、アーサー (2003). 「東エクアドルの形成期の年表」 (PDF). J. スコット・レイモンド (編). 形成期のエクアドルの考古学. リチャード・L・バーガー. ワシントン D.C.: ダンバートン・オークス、ハーバード大学評議員会. p. 541. ISBN 0-88402-292-7. 2012年2月11日にオリジナル(PDF)からアーカイブ。2008年7月18日に閲覧。陶器以前の集落や陶器を使用しない集落、そして後の陶器使用社 会は、紀元前500年よりはるか以前にオリエンテ地方のいくつかの地域に既に存在していた可能性が高い。 14. リッピ、ロナルド・D. (1996). 『エクアドル第一革命:古代エクアドルにおける農業生活の発展』. キト:アンデス歴史人類学研究所. 15. エリックソン、クラーク (2000). 「モクソス平原の居住丘陵」 (PDF). 低地の考古学。モンテビデオ:207–226頁。2008年7月18日閲覧。 16. ルーズベルト、アンナ・C.(2000)。「海洋・高地・森林のダイナミクス」。南アメリカ。アメリカ先住民の歴史(ケンブリッジ版)。第III巻(第3 版)。ケンブリッジ:ケンブリッジ大学出版局。pp. 264–349 [344]. ISBN 0-521-63075-4. 同様に、文化の精緻化は、従来の理論が予測したような社会組織と結びついていたわけではない。芸術や技術、記念碑建造という形の精緻化は、中央集権的な統 制行政の証拠がない両地域で確認された。 17. 島田泉 (2000). 「アンデス地域の多様性の進化:地域形成(紀元前 500 年~西暦 600 年)」。フランク・サロモン(編)。南アメリカ。ケンブリッジ・アメリカ大陸先住民史。第 III 巻。スチュワート・B・シュワルツ(第 3 版)。ケンブリッジ:ケンブリッジ大学出版局。ISBN 0-521-63075-4。 18. ジェームズ・D・ルドルフ (1991). 『エクアドル:国別研究』. 国会図書館国別研究. ワシントンD.C.: 国会図書館. LCCN 91009494. 19. ホセ・ルイス・エスピノサ E.、トメバンバ、プマプンゴ、ハトゥン・カニャール 『エクアドル考古学 2010』 20. ジュイヤール、ガエタン。「エクアドル考古学 | 雑誌 | インカになりたいなら…幸せになれ」エクアドル考古学。 21. イングリッド・フェルナンデス、上アマゾンゴムブームと先住民の権利 1900-1925 フロリダ・ガルフコースト大学 22. ルイス、ジャン・L. (2006年5月). 未開の地における文明人:アマゾンゴムブーム期におけるゴム、人種、文明 (PDF) (MoA論文). サスカチュワン大学. 2013年6月14日にオリジナル (PDF) からアーカイブ. 23. テキサコ石油会社のエクアドルにおける過去の事業背景 2011年8月16日ウェイバックマシンにアーカイブ 24. 「疫学対疫学:エクアドル・アマゾン盆地における石油開発の事例」ije.oxfordjournals.org. 2012年7月17日オリジナルからアーカイブ。2022年2月2日取得。 25. カーリー・ギリス、エクアドル対シェブロン・テキサコ:略史 2011年4月27日 26. サイモン・ロメロとクリフォード・クラウス、エクアドル裁判官、シェブロンに90億ドルの支払いを命じる NYTimes 2011年2月14日 27. オビエド・アレクシス(2023年5月31日)。「エクアドル:公共政策の浮き沈みにおける人種差別と民族的差別(Ecuador: racismo y discriminación étnica en el vaivén de la política pública)」。『Mundos Plurales - Revista Latinoamericana de Políticas y Acción Pública』9巻2号:111–133頁。doi:10.17141/mundosplurales.2.2022.5483. hdl:10644/9193. ISSN 2661-9075. 28. テレス、エドワード(2013年5月)。「人種的不平等に関するラテンアメリカの信念の理解」。American Journal of Sociology. 118 (6): 1559–1595. doi:10.1086/670268. S2CID 39970967. 29. ロイトマン、カレム(2017年12月)。「エクアドルにおけるメスティーソ人種差別」。民族・人種研究。40 (15): 2768–2786. doi:10.1080/01419870.2016.1260749. S2CID 152231395. 30. ガルシア=アラシル、アデラ(2006年)。「エクアドルにおける学歴と労働市場での収入における性別および民族性の差異」。World Development. 34 (2): 289–307. doi:10.1016/j.worlddev.2005.10.001. hdl:10261/103884. 31. Antón Sánchez, Jhon. 「社会および環境正義のための闘争における人種および民族の不平等に関する所見 | 人種、ジェンダー、グローバル化に関するイニシアチブ」。irgg.yale.edu。2023-09-05 取得。 32. de la Torre, Carlos (1999年1月)。「現代エクアドルにおける日常的な人種差別の形態:中流階級のインディアンたちの経験」。Ethnic & Racial Studies. 22: 92–112. doi:10.1080/014198799329602. 33. 「エクアドルにおける中国の鉱業と先住民の抵抗」。カーネギー国際平和財団。2025年3月18日取得。 34. 「エグゼクティブ・サマリー|権利の侵害」. {{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires |journal= (help) 35. ゲルラッハ、アレン. 『先住民、石油、政治:エクアドルの近現代史』. SRブックス、デラウェア州ウィルミントン. 2003 36. NORMLEX 国際労働機関(ILO) 37. 「エクアドル統計の歴史的考察」. 国立統計・国勢調査院: 16. 2015. 38. グリハルバ、マヌエル・ミーニョ (2022-08-01). 「移行期のエクアドル人口、1846–1889年」. スペイン語学術誌『国立歴史アカデミー紀要』. 100 (207): 95. ISSN 2773-7381. 2025年5月31日閲覧。 39. 『エクアドル統計の歴史的考察』. 2015年. p. 55. 2025年7月22日閲覧。 40. 「2022年人口・住宅センサス」. 2023年9月21日. 2023年9月21日閲覧。 41. 「エクアドル国勢調査」。INEC。2022–2023年。2025年6月30日閲覧。 42. 「エクアドル共和国憲法」。2015年10月17日時点のオリジナルからアーカイブ。2014年9月13日閲覧。 |

| Confederación de Nacionalidades Indígenas del Ecuador (CONAIE), Indigenous rights organization of Ecuador |

|

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Indigenous_peoples_in_Ecuador |

★エクアドルを知るための60章 / 新木秀和編著, 第2版. - 東京 : 明石書店 , 2012.12. - (エリア・スタディーズ ; 57)

| はじめに 第2版刊行にあたって I. 自然環境とその利用 第1章 自然環境――豊かな自然、多様な地域 【コラム1】「赤道」はどこに 第2章 環境利用と生活――赤道山地の生態とその利用 II. 社会の形成と発展 第3章 先史時代――商業活動を通して各地を経めぐった先住民 第4章 植民地時代――スペイン植民地の諸相 第5章 独立・国家形成と地域の再編――エクアドルの誕生 第6章 19世紀のエクアドル――カウディーリョ支配からガルシア・モレノ時代へ 第7章 自由主義革命――エロイ・アルファロと自由主義支配の時代 【コラム2】交通機関とマスメディア 第8章 政治の流れ――ポピュリズム・軍政・民主化/59 第9章 政治アクターとしての軍――拡大された役割と高い威信 第10章 国境の政治学――対ペルー国境紛争とナショナリズム 第11章 民主化の諸問題――参加拡大と政治危機の弁証法 第12章 コレア政権――左派政権による「市民革命」 第13章 経済ブームから経済危機へ――保護的輸出経済の転換と経済自由化の明暗 第14章 社会問題の諸相――格差構造と貧困 III. 文化とアイデンティティの探求 第15章 先史時代の諸遺跡――モニュメントの不在 第16章 博物館――待たれる展示活動の活性化 第17章 文化遺産の政治学――政治と経済に翻弄されるインカの遺跡 【コラム3】メディアのなかの「エクアドル」 第18章 ナショナルアイデンティティ――エクアドル人とは誰か 第19章 先住民のアイデンティティ――先住民とは誰か 第20章 先住民運動――議場に響く先住民の声 第21章 アフロ系エクアドル人――黒人の歴史と社会 第22章 女性の歩み――抑圧からのエンパワーメント IV. 豊かな生活文化 第23章 教育制度――格差の是正を目指して 第24章 子どもと学校――教育支援を受けるシエラ北部の子どもたち 第25章 先住民の二言語教育――多文化共存・共生に向けた新たな挑戦 第26章 エクアドル文学――社会性あふれる作品の宝庫 第27章 表現の可能性への多彩な挑戦――エクアドルの現代小説 第28章 フォークロアの空間――現代社会に息づく民話・伝説・神話 第29章 エクアドル美術の5000年――赤道直下の国に花咲く個性 第30章 20世紀の現代美術作家たち――モダニズムの系譜 第31章 音楽――豊かな楽曲と音楽家たち 第32章 宗教――圧倒的なカトリック、進出するプロテスタント 【コラム4】エル・シスネの聖母と巡礼 第33章 食文化――エクアドル料理を楽しむ 第34章 スポーツ――エクアドルサッカーチーム、ワールドカップへの道 V. 都市の風景 第35章 キト――歴史を刻む高地都市 第36章 世界遺産となったキト旧市街の建築――地震に耐えたカトリックの世界 第37章 グアヤキル――最大の港湾都市 第38章 クエンカ――南部の文化都市 VI. 地域と民族の活力 第39章 歴史のなかのアマゾン――破壊と変容、そして生成のプロセス 第40章 アマゾンの民族文化――彩り豊かな文化とアイデンティティ 第41章 アマゾンのエコツーリズム――先住民からの誘い 第42章 開発のなかのアマゾン――石油開発と先住民社会の変容 第43章 ガラパゴスの生物研究――進化論の舞台を探訪する(1) 第44章 ガラパゴスのエコツーリズム――進化論の舞台を探訪する(2) 【コラム5】ガラパゴスの人間社会 第45章 オタバロ――国際化する先住民の経済活動と社会変容 第46章 コタカチ――環境保全郡の挑戦 第47章 サリナス――自立発展のモデル地域 第48章 黒人が暮らす村の1日――エクアドル・コロンビアにまたがる黒人世界 第49章 バイーア・デ・カラケス――エコシティ宣言による街の再生 第50章 マンタ――水産業と国際空港の発展 VII. 開発の歩みと展望 第51章 フェアトレード――美味しいコーヒーと持続可能な地域づくりをつなげる 第52章 マハグアール――巨大マングローブの森 第53章 タグア――グリーンコンシューマーの試み 【コラム6】パナマ帽 第54章 バナナ――世界最大の輸出国エクアドル 第55章 農村開発――多民族が共存するための開発を目指して 第56章 農業部門の再編――多様化が進むコスタと停滞するシエラ VIII. 対外関係 第57章 対外関係と人の移動――多角化するエクアドルの国際関係 第58章 対日関係の歩み――赤道下に根づく日本人の社会 【コラム7】野口英世の足跡 第59章 古川拓殖とマニラ麻栽培――日本人移住者の足跡 【コラム8】ビルカバンバと大谷孝吉病院 第60章 移民――中国系・レバノン系・ユダヤ人の知られざる歴史 エクアドルを知るためのブックガイド |

エクアドル先住民研究リソース

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

CC

Copyleft,

CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099