ジョン・ロールズ

John Bordley Rawls, 1921-2002

☆ ジョン・ボードリー・ロールズ(John Bordley Rawls,1921年2月21日 - 2002年11月24日)は、近代リベラルの伝統に基づくアメリカの道徳・法・政治哲学者である。ロールズは20世紀において最も影響力のあ る政治哲学者の一人と評されている。ロールズは後の研究者たちに「配分的正義」の理論家であると評価されている(→「ジョン・ロールズ『正義論』解説」)。

| John

Bordley Rawls (/rɔːlz/;[2] February 21, 1921 – November 24, 2002)

was

an American moral, legal and political philosopher in the modern

liberal tradition.[3][4] Rawls has been described as one of the most

influential political philosophers of the 20th century.[5] In 1990, Will Kymlicka wrote in his introduction to the field that "it is generally accepted that the recent rebirth of normative political philosophy began with the publication of John Rawls's A Theory of Justice in 1971".[6][7] Rawls's theory of "justice as fairness" recommends equal basic liberties, equality of opportunity, and facilitating the maximum benefit to the least advantaged members of society in any case where inequalities may occur. Rawls's argument for these principles of social justice uses a thought experiment called the "original position", in which people deliberately select what kind of society they would choose to live in if they did not know which social position they would personally occupy. In his later work Political Liberalism (1993), Rawls turned to the question of how political power could be made legitimate given reasonable disagreement about the nature of the good life. Rawls received both the Schock Prize for Logic and Philosophy and the National Humanities Medal in 1999. The latter was presented by President Bill Clinton in recognition of how his works "revived the disciplines of political and ethical philosophy with his argument that a society in which the most fortunate help the least fortunate is not only a moral society but a logical one".[8] Among contemporary political philosophers, Rawls is frequently cited by the courts of law in the United States and Canada[9] and referred to by practicing politicians in the United States and the United Kingdom. In a 2008 national survey of political theorists, based on 1,086 responses from professors at accredited, four-year colleges and universities in the United States, Rawls was voted first on the list of "Scholars Who Have Had the Greatest Impact on Political Theory in the Past 20 Years".[10] |

ジョン・

ボードリー・ロールズ(John Bordley Rawls, /rɔ-lz/; [2] 1921年2月21日 -

2002年11月24日)は、近代リベラルの伝統に基づくアメリカの道徳・法・政治哲学者である[3][4]。ロールズは20世紀において最も影響力のあ

る政治哲学者の一人と評されている[5]。 1990年、ウィル・キムリッカはこの分野の入門書の中で、「最近の規範的政治哲学の再生は、1971年に出版されたジョン・ロールズの『正義論』から始 まったと一般に受け止められている」と書いている[6][7]。ロールズの「公正としての正義」の理論は、平等な基本的自由、機会の平等、そして不平等が 生じる可能性のあるいかなる場合においても、社会の最も恵まれない構成員に対して最大限の利益を促進することを推奨している。このような社会正義の原則を 主張するロールズの議論では、「原初的立場」と呼ばれる思考実験が用いられている。後の著作『政治的自由主義』(1993年)で、ロールズは、善き生活の 本質について合理的な意見の相違がある場合、政治権力をいかにして合法的なものにできるかという問題に目を向けた。 ロールズは1999年、論理学と哲学のためのショック賞と国家人文賞を受賞。後者は、「最も恵まれた者が最も恵まれない者を助ける社会は、道徳的な社会で あるだけでなく、論理的な社会でもあるという彼の主張によって、政治哲学と倫理哲学の学問分野を復活させた」ことが評価され、ビル・クリントン大統領から 贈られたものである[8]。 現代の政治哲学者の中でも、ロールズはアメリカやカナダの法廷で頻繁に引用され[9]、アメリカやイギリスの実務政治家によって参照されている。2008 年に行われた政治理論家を対象とした全国調査において、アメリカ国内の4年制大学の教授から寄せられた1,086の回答から、ロールズは「過去20年間で 政治理論に最も大きな影響を与えた学者」のリストの第1位に選ばれた[10]。 |

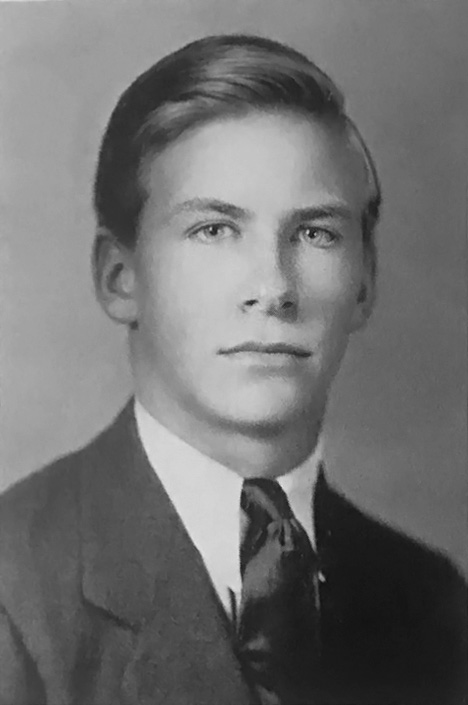

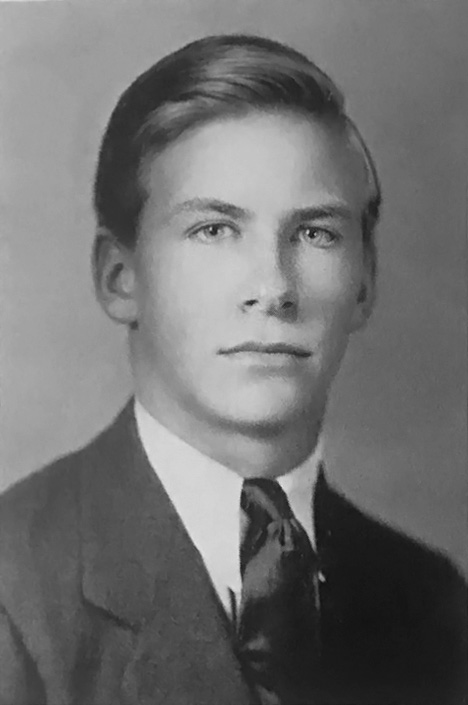

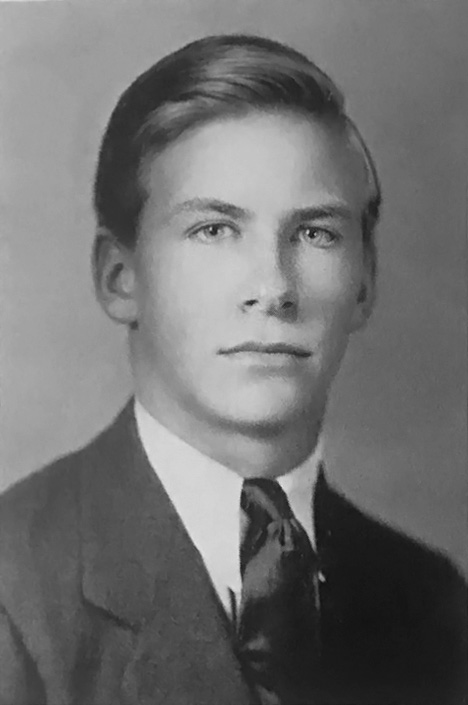

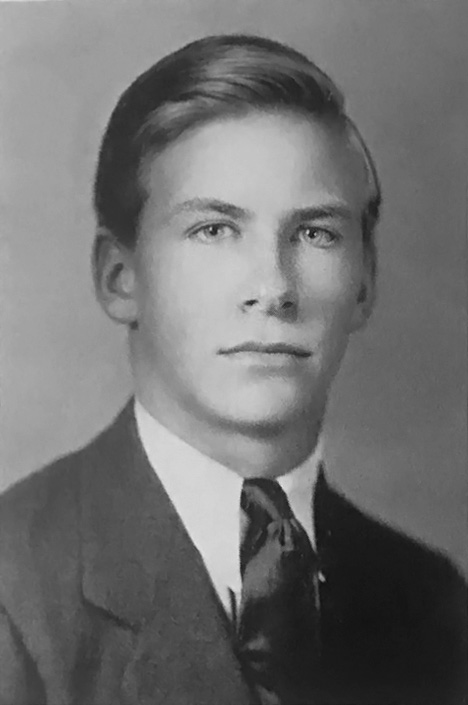

| Biography Early life and education Rawls was born on February 21, 1921, in Baltimore, Maryland.[11] He was the second of five sons born to William Lee Rawls, a prominent Baltimore attorney, and Anna Abell Stump Rawls.[12][13] Tragedy struck Rawls at a young age: Two of his brothers died in childhood because they had contracted fatal illnesses from him. ... In 1928, the seven-year-old Rawls contracted diphtheria. His brother Bobby, younger by 20 months, visited him in his room and was fatally infected. The next winter, Rawls contracted pneumonia. Another younger brother, Tommy, caught the illness from him and died.[14] Rawls's biographer Thomas Pogge calls the loss of the brothers the "most important events in John's childhood."  Photo portrait of a young man with short hair wearing a suit and tie Rawls as a Kent School senior, 1937 Part of a series on Liberalism Rawls graduated in Baltimore before enrolling in the Kent School, an Episcopalian preparatory school in Connecticut. Upon graduation in 1939, Rawls attended Princeton University, where he was accepted into The Ivy Club and the American Whig-Cliosophic Society. At Princeton, Rawls was influenced by Norman Malcolm, Ludwig Wittgenstein's student. During his last two years at Princeton, he "became deeply concerned with theology and its doctrines." He considered attending a seminary to study for the Episcopal priesthood and wrote an "intensely religious senior thesis (BI)."[15] In his 181-page long thesis titled "Meaning of Sin and Faith," Rawls attacked Pelagianism because it "would render the Cross of Christ to no effect."[16] His argument was partly drawn from Karl Marx's article On the Jewish Question, which criticized the idea that natural inequality in ability could be a just determiner of the distribution of wealth in society. Even after Rawls became an atheist, many of the anti-Pelagian arguments he used were repeated in A Theory of Justice. Rawls graduated from Princeton in 1943 with a Bachelor of Arts, summa cum laude.[13] Military service, 1943–46 Rawls enlisted in the U.S. Army in February 1943. During World War II, Rawls served as an infantryman in the Pacific, where he served a tour of duty in New Guinea and was awarded a Bronze Star; and the Philippines, where he endured intensive trench warfare and witnessed traumatizing scenes of violence and bloodshed.[17] It was there that he lost his Christian faith and became an atheist.[15][18][19] Following the surrender of Japan, Rawls became part of General MacArthur's occupying army[13] and was promoted to sergeant. But he became disillusioned with the military when he saw the aftermath of the atomic blast in Hiroshima. Rawls then disobeyed an order to discipline a fellow soldier, "believing no punishment was justified," and was "demoted back to a private." Disenchanted, he left the military in January 1946.[17] Academic career In early 1946, Rawls returned to Princeton to pursue a doctorate in moral philosophy. He married Margaret Warfield Fox, a Brown University graduate, in 1949. They had four children: Anne Warfield, Robert Lee, Alexander Emory, and Elizabeth Fox.[13] Rawls received his PhD from Princeton in 1950 after completing a doctoral dissertation titled A Study in the Grounds of Ethical Knowledge: Considered with Reference to Judgments on the Moral Worth of Character. His PhD included a year of study at Cornell. Rawls taught at Princeton until 1952 when he received a Fulbright Fellowship to Christ Church at Oxford University, where he was influenced by the liberal political theorist and historian Isaiah Berlin and the legal theorist H. L. A. Hart. After returning to the United States, he served first as an assistant and then associate professor at Cornell University. In the fall of 1953 Rawls became an assistant professor at Cornell University, joining his mentor Norman Malcolm in the Philosophy Department. Three years later Rawls received tenure at Cornell. During the 1959–60 academic year, Rawls was a visiting professor at Harvard, and he was appointed in 1960 as a professor in the humanities division at MIT. Two years later, he returned to Harvard as a professor of philosophy, and he remained there until reaching mandatory retirement age in 1991. In 1962, he achieved a tenured position at MIT. That same year, he moved to Harvard University, where he taught for almost forty years and where he trained some of the leading contemporary figures in moral and political philosophy, including Sibyl A. Schwarzenbach, Thomas Nagel, Allan Gibbard, Onora O'Neill, Adrian Piper, Arnold Davidson, Elizabeth S. Anderson, Christine Korsgaard, Susan Neiman, Claudia Card, Rainer Forst, Thomas Pogge, T. M. Scanlon, Barbara Herman, Joshua Cohen, Thomas E. Hill Jr., Gurcharan Das, Andreas Teuber, Henry S. Richardson, Nancy Sherman, Samuel Freeman and Paul Weithman. He held the James Bryant Conant University Professorship at Harvard.[20] Rawls was, for a time, a member of the Mont Pèlerin Society. He was put forward for membership by Milton Friedman in 1968, and withdrew from the society three years later, just before his A Theory of Justice was published.[21] Later life Rawls rarely gave interviews and, having both a stutter (partially caused by the deaths of two of his brothers, who died through infections contracted from Rawls) and a "bat-like horror of the limelight," did not become a public intellectual despite his fame. He instead remained committed mainly to his academic and family life.[12] In 1995, he had the first of several strokes, severely impeding his ability to continue to work. He was nevertheless able to complete The Law of Peoples, the most complete statement of his views on international justice and published in 2001 shortly before his death Justice as Fairness: A Restatement, a response to criticisms of A Theory of Justice. Rawls died from heart failure at his home in Lexington, Massachusetts, on November 24, 2002, at age 81.[3] He was buried at the Mount Auburn Cemetery in Massachusetts. He was survived by his wife, four children, and four grandchildren.[22] |

略歴 生い立ちと教育 ロールズは1921年2月21日、メリーランド州ボルチモアで生まれた[11]。 ボルチモアの著名な弁護士ウィリアム・リー・ロールズとアンナ・アベル・スタンプ・ロールズの間に生まれた5人兄弟の次男である[12][13]: 彼の兄弟のうち2人は、彼から致命的な病気をうつされ、幼少期に亡くなっている。1928年、7歳のロールズはジフテリアにかかった。20ヶ月年下の弟ボ ビーが彼の部屋を訪れ、致命的な感染を起こした。翌年の冬、ロールズは肺炎にかかった。もう一人の弟トミーも肺炎にかかり、死亡した[14]。 ロールズの伝記作家であるトーマス・ポッゲは、兄弟を失ったことを "ジョンの子供時代における最も重要な出来事 "と呼んでいる。  スーツとネクタイを着用した短髪の若者の肖像写真 ケント・スクール4年生時代のロールズ、1937年 リベラリズム ロールズはボルチモアを卒業後、コネチカット州にあるエピスコパリア系の予備校ケント・スクールに入学した。1939年に卒業すると、プリンストン大学に 入学し、アイビー・クラブとアメリカン・ウィッグ・クレオソフィック・ソサエティに入会した。プリンストン大学では、ルートヴィヒ・ウィトゲンシュタイン の弟子ノーマン・マルコムの影響を受ける。プリンストン大学での最後の2年間、彼は「神学とその教義に深く関心を持つようになった」。ロールズは「罪と信 仰の意味」と題された181ページに及ぶ長い論文の中で、ペラギウス主義を攻撃した。ロールズが無神論者となった後も、彼が用いた反ペラギウス派の主張の 多くは『正義論』の中で繰り返された。ロールズは1943年にプリンストン大学を優秀な成績で卒業。 兵役、1943-46年 1943年2月、ロールズはアメリカ陸軍に入隊。第二次世界大戦中、ロールズは歩兵として太平洋戦争に従軍し、ニューギニアでは青銅星章を授与され、フィ リピンでは激しい塹壕戦に耐え、暴力と流血のトラウマとなる光景を目の当たりにした[17]。 日本の降伏後、ロールズはマッカーサー元帥の占領軍の一員となり[13]、軍曹に昇進した。しかし、広島の原爆の後遺症を見て軍に幻滅。ロールズはその 後、「処罰は正当化されないと考え」仲間の兵士を懲戒する命令に従わず、「二等兵に降格させられた」。幻滅した彼は1946年1月に軍を去った[17]。 学者としてのキャリア 1946年初頭、ロールズは道徳哲学の博士号を取得するためにプリンストン大学に戻る。1949年、ブラウン大学出身のマーガレット・ウォーフィールド・ フォックスと結婚。二人の間には4人の子供がいた: アン・ウォーフィールド、ロバート・リー、アレクサンダー・エモリー、エリザベス・フォックスである[13]。 1950年、プリンストン大学で「倫理的知識の根拠に関する研究(A Study in the Grounds of Ethical Knowledge)」と題する博士論文を執筆し、博士号を取得: 博士論文のタイトルは『A Study in Grounds of Ethical Knowledge: Considered with Reference on Judgments on the Moral Worth of Character』。博士号取得後、コーネル大学で1年間学んだ。1952年までプリンストン大学で教鞭を執った後、フルブライト奨学金を得てオックス フォード大学のクライスト・チャーチに留学し、リベラル派の政治理論家で歴史家のアイザイア・バーリンや法学者のH・L・A・ハートの影響を受ける。帰国 後、コーネル大学で助教授、准教授を歴任。 1953年秋、ロールズはコーネル大学の助教授となり、恩師ノーマン・マルコムとともに哲学科に配属された。その3年後、ロールズはコーネル大学で終身在 職権を獲得した。1959年から60年の間、ロールズはハーバード大学の客員教授を務め、1960年にはマサチューセッツ工科大学の人文科学部門の教授に 任命された。2年後、哲学教授としてハーバード大学に戻り、1991年に定年を迎えるまで同大学に在籍した。 1962年、MITで終身在職権を獲得。同年、ハーバード大学に移り、約40年間教鞭を執り、シビルA.シュヴァルツェンバッハ、トーマス・ネーゲル、ア ラン・ギバード、オノラ・オニール、エイドリアン・パイパー、アーノルド・デヴィッドソン、エリザベス・S.アンダーソン、クリスティン・コルスガード、 スーザン・ニーマン、クラウディア・カード、ライナー・フォルスト、トーマス・ポッゲ、T.M.スカンロン、バーバラ・ハーマン、ジョシュア・コーエン、 トーマス・E.ヒルJr、 グルチャラン・ダス、アンドレアス・テューバー、ヘンリー・S・リチャードソン、ナンシー・シャーマン、サミュエル・フリーマン、ポール・ワイスマン。 ハーバード大学ではジェームズ・ブライアント・コナント大学教授職を務めた[20]。 一時期、モン・ペレラン協会の会員であった。1968年にミルトン・フリードマンによって会員に推され、3年後に『正義論』が出版される直前に退会した [21]。 その後の人生 ロールズはほとんどインタビューに応じず、吃音(ロールズから感染した感染症で亡くなった2人の兄の死が原因のひとつ)と「脚光を浴びることをコウモリの ように恐れる」性格のため、名声があったにもかかわらず、公の知識人になることはなかった。その代わり、彼は主に学問と家庭生活に専念していた[12]。 1995年、何度目かの脳卒中で倒れ、仕事を続けることに大きな支障をきたした。それにもかかわらず、国際正義に関する彼の見解の最も完全な声明であり、 死の直前の2001年に出版された『公正としての正義』(The Law of Peoples)を完成させることができた: 正義論』に対する批判への回答として、『公正としての正義:再定義』を出版した。2002年11月24日、マサチューセッツ州レキシントンの自宅で心不全 により死去、享年81歳[3]。マサチューセッツ州のマウント・オーバーン墓地に埋葬された。妻と4人の子供、4人の孫がいた[22]。 |

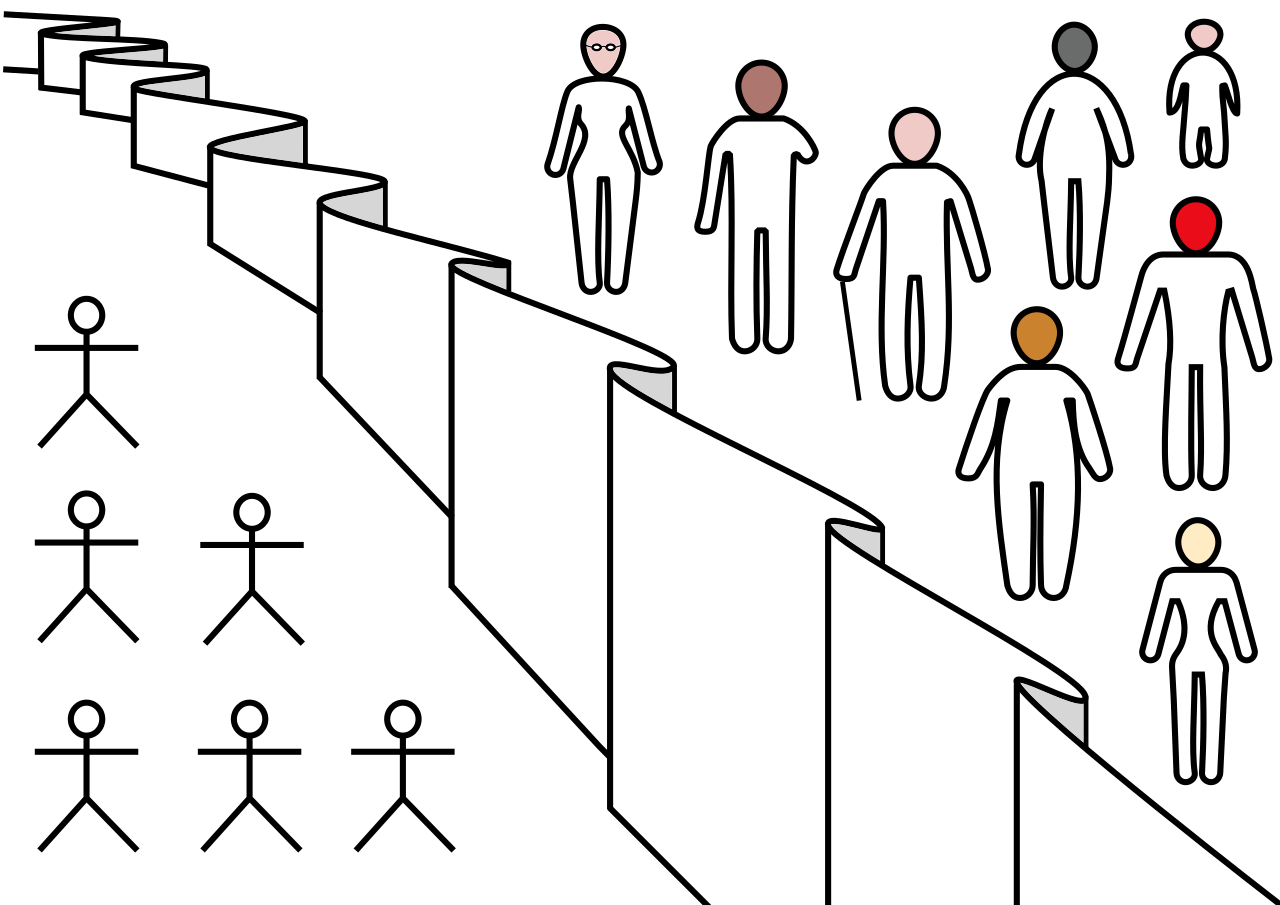

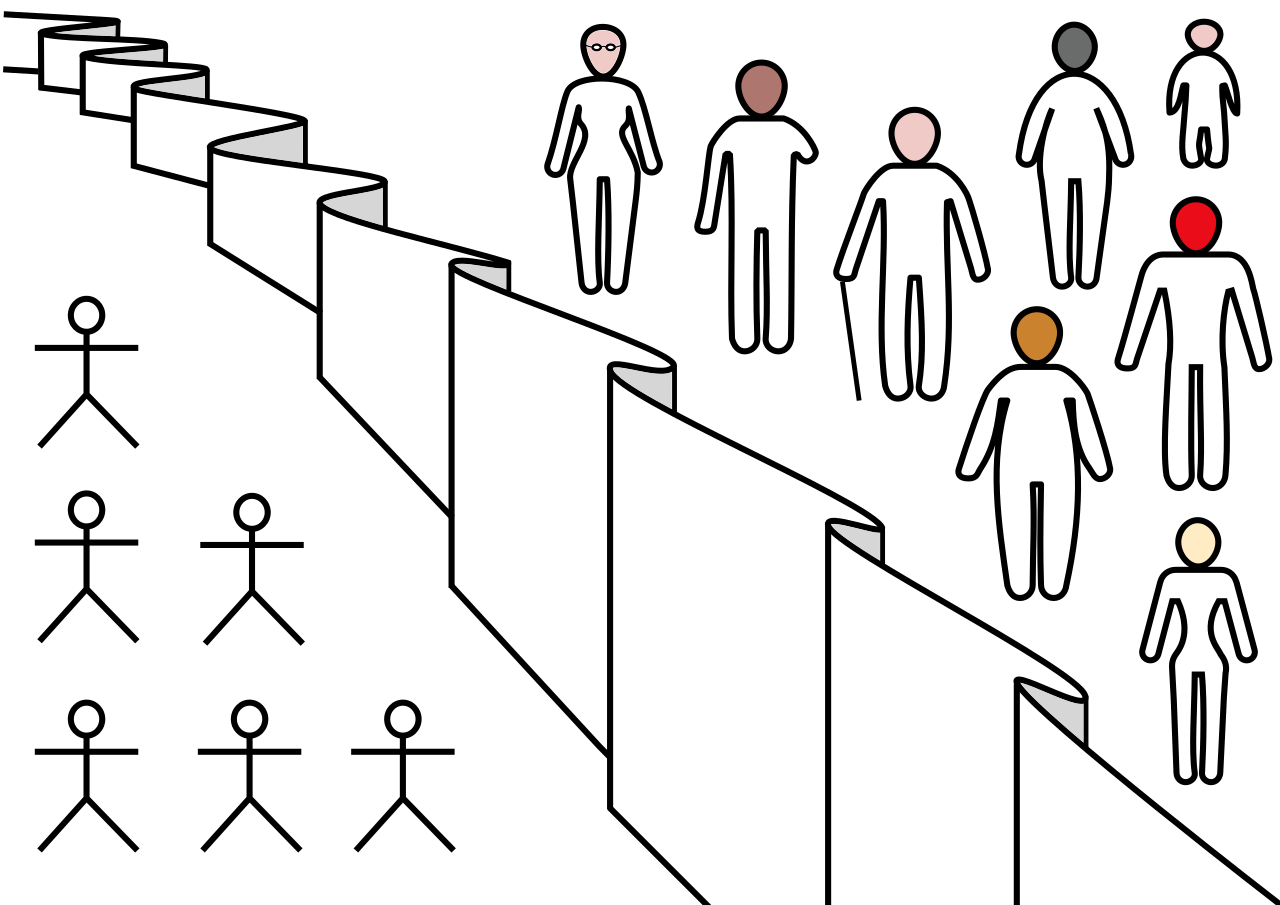

| Political Thought Rawls published three main books. The first, A Theory of Justice, focused on distributive justice and attempted to reconcile the competing claims of the values of freedom and equality. The second, Political Liberalism, addressed the question of how citizens divided by intractable religious and philosophical disagreements could come to endorse a constitutional democratic regime. The third, The Law of Peoples, focused on the issue of global justice. A Theory of Justice Main article: A Theory of Justice A Theory of Justice, published in 1971, aimed to resolve the seemingly competing claims of freedom and equality. The shape Rawls's resolution took, however, was not that of a balancing act that compromised or weakened the moral claim of one value compared with the other. Rather, his intent was to show that notions of freedom and equality could be integrated into a seamless unity he called justice as fairness. By attempting to enhance the perspective which his readers should take when thinking about justice, Rawls hoped to show the supposed conflict between freedom and equality to be illusory. Rawls's A Theory of Justice (1971) includes a thought experiment he called the "original position." The intuition motivating its employment is this: the enterprise of political philosophy will be greatly benefited by a specification of the correct standpoint a person should take in their thinking about justice. When we think about what it would mean for a just state of affairs to obtain between persons, we eliminate certain features (such as hair or eye color, height, race, etc.) and fixate upon others. Rawls's original position is meant to encode all of our intuitions about which features are relevant, and which irrelevant, for the purposes of deliberating well about justice. The original position is Rawls's hypothetical scenario in which a group of persons is set the task of reaching an agreement about the kind of political and economic structure they want for a society, which they will then occupy. Each individual, however, deliberates behind a "veil of ignorance": each lacks knowledge, for example, of their gender, race, age, intelligence, wealth, skills, education and religion. The only thing that a given member knows about themselves is that they are in possession of the basic capacities necessary to fully and willfully participate in an enduring system of mutual cooperation; each knows they can be a member of the society.  Green book cover A Theory of Justice, 1st ed. Illustration showing two groups and a wall (or veil) separating them: the first group at left are uniform stick figures, while the group at right are more diverse in terms of gender, race, and other qualities Visual illustration of the "original position" and "veil of ignorance"  Citizens making choices about their society are asked to make them from an "original position" of equality (at left) behind a "veil of ignorance" (wall, center), without knowing what gender, race, abilities, tastes, wealth, or position in society they will have (at right). Rawls claims this will cause them to choose "fair" policies. Rawls posits two basic capacities that the individuals would know themselves to possess. First, individuals know that they have the capacity to form, pursue and revise a conception of the good, or life plan. Exactly what sort of conception of the good this is, however, the individual does not yet know. It may be, for example, religious or secular, but at the start, the individual in the original position does not know which. Second, each individual understands themselves to have the capacity to develop a sense of justice and a generally effective desire to abide by it. Knowing only these two features of themselves, the group will deliberate in order to design a social structure, during which each person will seek their maximal advantage. The idea is that proposals that we would ordinarily think of as unjust—such as that black people or women should not be allowed to hold public office—will not be proposed, in this, Rawls's original position, because it would be irrational to propose them. The reason is simple: one does not know whether he himself would be a woman or a black person. This position is expressed in the difference principle, according to which, in a system of ignorance about one's status, one would strive to improve the position of the worst off, because he might find himself in that position. Rawls develops his original position by modeling it, in certain respects at least, after the "initial situations" of various social contract thinkers who came before him, including Thomas Hobbes, John Locke and Jean-Jacques Rousseau. Each social contractarian constructs their initial situation somewhat differently, having in mind a unique political morality they intend the thought experiment to generate.[23] Iain King has suggested the original position draws on Rawls's experiences in post-war Japan, where the US Army was challenged with designing new social and political authorities for the country, while "imagining away all that had gone before."[17] In social justice processes, each person early on makes decisions about which features of persons to consider and which to ignore. Rawls's aspiration is to have created a thought experiment whereby a version of that process is carried to its completion, illuminating the correct standpoint a person should take in their thinking about justice. If he has succeeded, then the original position thought experiment may function as a full specification of the moral standpoint we should attempt to achieve when deliberating about social justice. In setting out his theory, Rawls described his method as one of "reflective equilibrium," a concept which has since been used in other areas of philosophy. Reflective equilibrium is achieved by mutually adjusting one's general principles and one's considered judgements on particular cases, to bring the two into line with one another. Principles of justice Rawls derives two principles of justice from the original position. The first of these is the Liberty Principle, which establishes equal basic liberties for all citizens. 'Basic' liberty entails the (familiar in the liberal tradition) freedoms of conscience, association and expression as well as democratic rights; Rawls also includes a personal property right, but this is defended in terms of moral capacities and self-respect,[24] rather than an appeal to a natural right of self-ownership (this distinguishes Rawls's account from the classical liberalism of John Locke and the libertarianism of Robert Nozick). Rawls argues that a second principle of equality would be agreed upon to guarantee liberties that represent meaningful options for all in society and ensure distributive justice. For example, formal guarantees of political voice and freedom of assembly are of little real worth to the desperately poor and marginalized in society. Demanding that everyone have exactly the same effective opportunities in life would almost certainly offend the very liberties that are supposedly being equalized. Nonetheless, we would want to ensure at least the "fair worth" of our liberties: wherever one ends up in society, one wants life to be worth living, with enough effective freedom to pursue personal goals. Thus, participants would be moved to affirm a two-part second principle comprising Fair Equality of Opportunity and the famous (and controversial[25]) difference principle. This second principle ensures that those with comparable talents and motivation face roughly similar life chances and that inequalities in society work to the benefit of the least advantaged. Rawls held that these principles of justice apply to the "basic structure" of fundamental social institutions (such as the judiciary, the economic structure and the political constitution), a qualification that has been the source of some controversy and constructive debate (see the work of Gerald Cohen). Rawls's theory of justice stakes out the task of equalizing the distribution of primary social goods to those least advantaged in society and thus may be seen as a largely political answer to the question of justice, with matters of morality somewhat conflated into a political account of justice and just institutions. Relational approaches to the question of justice, by contrast, seek to examine the connections between individuals and focuses on their relations in societies, with respect to how these relationships are established and configured.[26] Rawls further argued that these principles were to be 'lexically ordered' to award priority to basic liberties over the more equality-oriented demands of the second principle. This has also been a topic of much debate among moral and political philosophers. Finally, Rawls took his approach as applying in the first instance to what he called a "well-ordered society ... designed to advance the good of its members and effectively regulated by a public conception of justice."[27] In this respect, he understood justice as fairness as a contribution to "ideal theory," the determination of "principles that characterize a well-ordered society under favorable circumstances."[28] Political Liberalism  Beige book cover with simple black and red shapes First edition of Political Liberalism In Political Liberalism (1993), Rawls turned towards the question of political legitimacy in the context of intractable philosophical, religious, and moral disagreement amongst citizens regarding the human good. Such disagreement, he insisted, was reasonable—the result of the free exercise of human rationality under the conditions of open enquiry and free conscience that the liberal state is designed to safeguard. The question of legitimacy in the face of reasonable disagreement was urgent for Rawls because his own justification of Justice as Fairness relied upon a Kantian conception of the human good that can be reasonably rejected. If the political conception offered in A Theory of Justice can only be shown to be good by invoking a controversial conception of human flourishing, it is unclear how a liberal state ordered according to it could possibly be legitimate. The intuition animating this seemingly new concern is actually no different from the guiding idea of A Theory of Justice, namely that the fundamental charter of a society must rely only on principles, arguments and reasons that cannot be reasonably rejected by the citizens whose lives will be limited by its social, legal, and political circumscriptions. In other words, the legitimacy of a law is contingent upon its justification being impossible to reasonably reject. This old insight took on a new shape, however, when Rawls realized that its application must extend to the deep justification of Justice as Fairness itself, which he had presented in terms of a reasonably rejectable (Kantian) conception of human flourishing as the free development of autonomous moral agency. The core of Political Liberalism is its insistence that in order to retain its legitimacy, the liberal state must commit itself to the "ideal of public reason." This roughly means that citizens in their public capacity must engage one another only in terms of reasons whose status as reasons is shared between them. Political reasoning, then, is to proceed purely in terms of "public reasons." For example: a Supreme Court justice deliberating on whether or not the denial to homosexuals of the ability to marry constitutes a violation of the 14th Amendment's Equal Protection Clause may not advert to his religious convictions on the matter, but he may take into account the argument that a same-sex household provides sub-optimal conditions for a child's development.[citation needed] This is because reasons based upon the interpretation of sacred text are non-public (their force as reasons relies upon faith commitments that can be reasonably rejected), whereas reasons that rely upon the value of providing children with environments in which they may develop optimally are public reasons—their status as reasons draws upon no deep, controversial conception of human flourishing. Rawls held that the duty of civility—the duty of citizens to offer one another reasons that are mutually understood as reasons—applies within what he called the "public political forum." This forum extends from the upper reaches of government—for example the supreme legislative and judicial bodies of the society—all the way down to the deliberations of a citizen deciding for whom to vote in state legislatures or how to vote in public referendums. Campaigning politicians should also, he believed, refrain from pandering to the non-public religious or moral convictions of their constituencies. The ideal of public reason secures the dominance of the public political values—freedom, equality, and fairness—that serve as the foundation of the liberal state. But what about the justification of these values? Since any such justification would necessarily draw upon deep (religious or moral) metaphysical commitments which would be reasonably rejectable, Rawls held that the public political values may only be justified privately by individual citizens. The public liberal political conception and its attendant values may and will be affirmed publicly (in judicial opinions and presidential addresses, for example) but its deep justifications will not. The task of justification falls to what Rawls called the "reasonable comprehensive doctrines" and the citizens who subscribe to them. A reasonable Catholic will justify the liberal values one way, a reasonable Muslim another, and a reasonable secular citizen yet another way. One may illustrate Rawls's idea using a Venn diagram: the public political values will be the shared space upon which overlap numerous reasonable comprehensive doctrines. Rawls's account of stability presented in A Theory of Justice is a detailed portrait of the compatibility of one—Kantian—comprehensive doctrine with justice as fairness. His hope is that similar accounts may be presented for many other comprehensive doctrines. This is Rawls's famous notion of an "overlapping consensus." Such a consensus would necessarily exclude some doctrines, namely, those that are "unreasonable", and so one may wonder what Rawls has to say about such doctrines. An unreasonable comprehensive doctrine is unreasonable in the sense that it is incompatible with the duty of civility. This is simply another way of saying that an unreasonable doctrine is incompatible with the fundamental political values a liberal theory of justice is designed to safeguard—freedom, equality and fairness. So one answer to the question of what Rawls has to say about such doctrines is—nothing. For one thing, the liberal state cannot justify itself to individuals (such as religious fundamentalists) who hold to such doctrines, because any such justification would—as has been noted—proceed in terms of controversial moral or religious commitments that are excluded from the public political forum. But, more importantly, the goal of the Rawlsian project is primarily to determine whether or not the liberal conception of political legitimacy is internally coherent, and this project is carried out by the specification of what sorts of reasons persons committed to liberal values are permitted to use in their dialogue, deliberations and arguments with one another about political matters. The Rawlsian project has this goal to the exclusion of concern with justifying liberal values to those not already committed—or at least open—to them. Rawls's concern is with whether or not the idea of political legitimacy fleshed out in terms of the duty of civility and mutual justification can serve as a viable form of public discourse in the face of the religious and moral pluralism of modern democratic society, not with justifying this conception of political legitimacy in the first place. Rawls also modified the principles of justice as follows (with the first principle having priority over the second, and the first half of the second having priority over the latter half): Each person has an equal claim to a fully adequate scheme of basic rights and liberties, which scheme is compatible with the same scheme for all; and in this scheme the equal political liberties, and only those liberties, are to be guaranteed their fair value. Social and economic inequalities are to satisfy two conditions: first, they are to be attached to positions and offices open to all under conditions of fair equality of opportunity; and second, they are to be to the greatest benefit of the least advantaged members of society. These principles are subtly modified from the principles in Theory. The first principle now reads "equal claim" instead of "equal right", and he also replaces the phrase "system of basic liberties" with "a fully adequate scheme of equal basic rights and liberties". The two parts of the second principle are also switched, so that the difference principle becomes the latter of the three. The Law of Peoples Main article: The Law of Peoples Although there were passing comments on international affairs in A Theory of Justice, it was not until late in his career that Rawls formulated a comprehensive theory of international politics with the publication of The Law of Peoples. He claimed there that "well-ordered" peoples could be either "liberal" or "decent". Rawls's basic distinction in international politics is that his preferred emphasis on a society of peoples is separate from the more conventional and historical discussion of international politics as based on relationships between states. Rawls argued that the legitimacy of a liberal international order is contingent on tolerating decent peoples, which differ from liberal peoples, among other ways, in that they might have state religions and deny adherents of minority faiths the right to hold positions of power within the state and might organize political participation via consultation hierarchies rather than elections. However, no well-ordered peoples may violate human rights or behave in an externally aggressive manner. Peoples that fail to meet the criteria of "liberal" or "decent" peoples are referred to as 'outlaw states', 'societies burdened by unfavorable conditions' or 'benevolent absolutisms', depending on their particular failings. Such peoples do not have the right to mutual respect and toleration possessed by liberal and decent peoples. Rawls's views on global distributive justice as they were expressed in this work surprised many of his fellow egalitarian liberals. For example, Charles Beitz had previously written a study that argued for the application of Rawls's Difference Principles globally. Rawls denied that his principles should be so applied, partly on the grounds that a world state does not exist and would not be stable. This notion has been challenged, as a comprehensive system of global governance has arisen, amongst others in the form of the Bretton Woods system, that serves to distribute primary social goods between human beings. It has thus been argued that a cosmopolitan application of the theory of justice as fairness is the more reasonable alternative to the application of The Law of Peoples, as it would be more legitimate towards all persons over whom political coercive power is exercised.[29] According to Rawls however, nation states, unlike citizens, were self-sufficient in the cooperative enterprises that constitute domestic societies. Although Rawls recognized that aid should be given to governments which are unable to protect human rights for economic reasons, he claimed that the purpose for this aid is not to achieve an eventual state of global equality, but rather only to ensure that these societies could maintain liberal or decent political institutions. He argued, among other things, that continuing to give aid indefinitely would see nations with industrious populations subsidize those with idle populations and would create a moral hazard problem where governments could spend irresponsibly in the knowledge that they will be bailed out by those nations who had spent responsibly. Rawls's discussion of "non-ideal" theory, on the other hand, included a condemnation of bombing civilians and of the American bombing of German and Japanese cities in World War II, as well as discussions of immigration and nuclear proliferation. He also detailed here the ideal of the statesman, a political leader who looks to the next generation and promotes international harmony, even in the face of significant domestic pressure to act otherwise. Rawls also controversially claimed that violations of human rights can legitimize military intervention in the violating states, though he also expressed the hope that such societies could be induced to reform peacefully by the good example of liberal and decent peoples. |

政治思想 ロールズは主に3冊の本を出版した。最初の『正義論』は、分配的正義に焦点を当て、自由と平等という価値観の相反する主張を調整しようとしたものである。 2冊目の『政治的自由主義』(Political Liberalism)は、難解な宗教的・哲学的意見の相違によって分断された市民が、いかにして立憲民主主義体制を支持するようになるかという問題を 扱った。第三の『諸国民の法』は、グローバルな正義の問題に焦点を当てたものである。 正義の理論 主な記事 正義論 1971年に出版された『正義論』は、自由と平等という一見相反する主張を解決することを目的としている。しかし、ロールズの解決策は、一方の価値の道徳 的主張を他方に比べて妥協させたり弱めたりするような、バランスを取るようなものではなかった。むしろ彼の意図は、自由と平等の概念が、公正としての正義 と呼ばれる継ぎ目のない統一体に統合されうることを示すことであった。ロールズは、読者が正義について考える際に取るべき視点を高めようとすることで、自 由と平等の対立が幻想であることを示そうとしたのである。 ロールズの『正義の理論』(1971年)には、彼が "オリジナル・ポジション "と呼ぶ思考実験が含まれている。その採用の動機となった直観は次のようなものである:正義について考える際に、人がとるべき正しい立場を明示することに よって、政治哲学の事業は大きな利益を得るだろう。人と人との間に公正な状態が得られるとはどういうことかを考えるとき、私たちは特定の特徴(髪や目の 色、身長、人種など)を排除し、他の特徴に注目する。ロールズの本来の立場は、正義についてよく考えるという目的のために、どの特徴が関連し、どの特徴が 無関係であるかについての私たちの直観をすべて符号化することを意図している。 原初の立場とは、ロールズが仮定したシナリオのことで、ある集団が、自分たちが望む社会の政治的・経済的構造について合意に達し、それを自分たちが占有す るというものである。しかし、各個人は「無知のヴェール」をかぶって審議している。たとえば、性別、人種、年齢、知性、富、技能、教育、宗教などについて の知識がない。あるメンバーが自分自身について知っている唯一のことは、相互協力の永続的なシステムに完全かつ意志を持って参加するために必要な基本的能 力を所有しているということである。  緑色の表紙 『正義論』第1版 2つのグループとそれらを隔てる壁(またはベール)を示すイラスト:左側の最初のグループは画一的な棒人間であり、右側のグループは性別、人種、その他の 資質においてより多様である。 「本来の立場」と「無知のベール」の視覚的図解  自分たちの社会について選択する市民は、性別、人種、能力、嗜好、富、社会における地位(右図)を知ることなく、「無知のヴェール」(壁、中央)の向こう 側にある平等の「原初の位置」(左図)から選択するよう求められる。ロールズは、これによって彼らが「公正な」政策を選択するようになると主張する。 ロールズは、個人が自分自身が持っていると知っている2つの基本的な能力を仮定している。第一に、個人は善の概念、すなわち人生設計を形成し、追求し、修 正する能力を持っていることを知っている。しかし、それがどのような善の概念なのか、個人はまだ知らない。例えば、宗教的なものであったり、世俗的なもの であったりするが、最初の段階では、元の立場にある個人はどちらなのかわからない。第二に、各個人は自分自身が正義感を育む能力を持ち、それを守ろうとす る一般的に効果的な願望を持っていることを理解している。この2つの特徴しか知らない集団は、社会構造を設計するために熟考を重ね、その間に各人が最大限 の利点を追求する。つまり、黒人や女性は公職に就くべきではないというような、通常であれば不公正であると考えられる提案は、ロールズの本来の立場では提 案されないということである。理由は簡単で、自分自身が女性になるか黒人になるかはわからないからである。この立場は差異原理で表現される。差異原理によ れば、自分の地位について無知であるシステムでは、人は最も不利な立場にある人の地位を向上させようと努力する。 ロールズは、トマス・ホッブズ、ジョン・ロック、ジャン=ジャック・ルソーなど、ロールズ以前に登場したさまざまな社会契約論者の「初期状況」をモデルに して、少なくともある点では独自の立場を展開している。それぞれの社会契約論者は、思考実験が生み出すことを意図している独自の政治道徳を念頭に置きなが ら、初期状況をいくらか異なるように構築している[23]。イアン・キングは、オリジナルの立場はロールズが戦後の日本で経験したことに由来していると示 唆している。 社会正義のプロセスにおいては、各人が早い段階で、どのような人物の特徴を考慮し、どのような人物を無視するかについて決定を下す。ロールズの願望は、そ のようなプロセスを完成させるための思考実験を行い、正義について考える際に人が取るべき正しい立場を明らかにすることである。もしロールズが成功したの であれば、この思考実験は、社会正義について熟慮する際に私たちが達成しようと試みるべき道徳的立場の完全な仕様として機能することになるだろう。 ロールズは自らの理論を打ち出すにあたって、その方法を「反省的均衡」と表現した。反省的均衡とは、一般的な原則と、特定のケースについての熟考された判 断を相互に調整し、両者を一致させることによって達成されるものである。 正義の原則 ロールズは元の立場から2つの正義の原理を導き出す。その第一は「自由原則」であり、すべての市民に平等な基本的自由を定めるものである。基本的な」自由 は、民主的権利と同様に、(自由主義の伝統ではお馴染みの)良心、結社、表現の自由を伴う。ロールズは個人的財産権も含むが、これは自己所有の自然権に訴 えるのではなく、道徳的能力と自尊心[24]の観点から擁護される(この点がロールズの説明をジョン・ロックの古典的自由主義やロバート・ノージックのリ バタリアニズムと区別している)。 ロールズは、社会のすべての人にとって有意義な選択肢となる自由を保証し、分配的公正を確保するために、第二の平等原則が合意されるだろうと主張する。例 えば、政治的発言権や集会の自由といった形式的な保障は、社会から疎外され、貧困にあえぐ人々にとってはほとんど意味をなさない。すべての人にまったく同 じ有効な生活機会を求めることは、平等化されるはずの自由そのものを侵害することになる。とはいえ、私たちは少なくとも自由の「公正な価値」を確保したい と思うだろう。社会のどこにいようとも、個人的な目標を追求するのに十分な有効な自由があり、生き甲斐のある人生を送りたいと思うものだ。従って、参加者 は公平な機会平等と有名な(そして物議を醸した[25])差異原則からなる2つの部分からなる第二原則を肯定するようになるだろう。この第二の原則は、同 等の才能と意欲を持つ人々がほぼ同様の人生のチャンスに直面し、社会における不平等が最も恵まれない人々の利益となるようにするものである。 ロールズは、これらの正義の原則は、基本的な社会制度(司法、経済構造、政治憲法など)の「基本構造」に適用されるとした。ロールズの正義論は、社会で最 も恵まれない人々への主要な社会財の分配を均等にするという課題を掲げており、したがって正義の問題に対する政治的な回答であると考えられる。これとは対 照的に、正義の問題に対する関係論的アプローチは、個人間のつながりを検討しようとし、これらの関係がどのように確立され構成されるかに関して、社会にお ける彼らの関係に焦点を当てている[26]。 ロールズはさらに、これらの原則は、第二の原則のより平等志向的な要求よりも基本的自由を優先させるために「語彙的に順序づけられる」べきであると主張し た。この点についても、道徳哲学者や政治哲学者の間で多くの議論が交わされてきた。 最後に、ロールズは自らのアプローチを、彼が「秩序ある社会......その構成員の善を増進させるように設計され、正義の公的概念によって効果的に規制 された社会」[27]と呼ぶものに第一義的に適用するものとしていた。この点において、彼は公正としての正義を「理想理論」への貢献、すなわち「好ましい 状況下で秩序ある社会を特徴づける原理」の決定として理解していた[28]。 政治的自由主義  黒と赤のシンプルなベージュの表紙 『政治的自由主義』初版 ロールズは『政治的自由主義』(1993年)の中で、人間の善に関して市民の間で哲学的、宗教的、道徳的に意見の相違があるという難問の中で、政治的正当 性の問題に目を向けた。このような意見の相違は合理的なものであり、自由主義国家が保護するために設計された、開かれた探究と自由な良心という条件の下で の人間の合理性の自由な行使の結果である、と彼は主張した。ロールズにとって、合理的な意見の相違に直面した場合の正当性の問題は緊急の課題であった。と いうのも、彼自身が正当化した「公正としての正義」は、カント的な人間的善の概念に依拠していたからである。もし『正義論』で提示された政治的概念が、論 争を呼ぶような人間繁栄の概念を持ち出すことでしか善であることを示すことができないのであれば、それに従って秩序づけられた自由主義国家がいかにして合 法的でありうるかは不明である。 つまり、社会の基本憲章は、その社会的、法的、政治的規定によって生活を制限されることになる市民が合理的に拒否することのできない原理、議論、理由のみ に依拠しなければならないということである。言い換えれば、法律の正当性は、その正当性が合理的に否定できないものであることが条件となる。しかし、この 古い洞察は、ロールズが、自律的な道徳的主体性の自由な発展としての人間の繁栄に関する合理的に拒否可能な(カント的な)概念という観点から提示した、公 正さとしての正義そのものの深い正当化にも適用されなければならないことに気づいたとき、新しい形をとることになった。 ポリティカル・リベラリズムの核心は、リベラル国家がその正統性を維持するためには、"公理性の理想 "にコミットしなければならないという主張である。これは大まかに言えば、市民はその公的能力において、理由としての地位が市民間で共有されている理由に よってのみ、互いに関与しなければならないということである。政治的推論は、純粋に "公的理由 "の観点から進められる。例えば、最高裁判事は、同性愛者の結婚を認めないことが憲法修正第14条の平等保護条項に違反するかどうかを審議する際に、自分 の宗教的信念を主張することはできないが、同性の家庭が子どもの成長に最適な条件ではないという主張は考慮することができる。 [聖典の解釈に基づく理由は非パブリックなものであるのに対し(理由としての効力は、合理的に拒否できる信仰上のコミットメントに依存している)、子ども が最適に成長できる環境を提供することの価値に依存する理由はパブリックな理由である。 ロールズは、礼節の義務、つまり市民が互いに理由と理解される理由を提供し合う義務は、彼が "公共の政治的場 "と呼ぶものの中で適用されるとした。このフォーラムは、例えば社会の最高立法機関や司法機関といった政府の上層部から、州議会で誰に投票するか、あるい は国民投票でどのように投票するかを決める市民の審議に至るまで広がっている。政治家はまた、有権者の宗教的・道徳的な信念に迎合することも控えるべきだ と彼は考えた。 公共の理性という理想は、自由主義国家の基盤として機能する、自由、平等、公正という公共の政治的価値の優位性を確保するものである。しかし、これらの価 値の正当化についてはどうだろうか。そのような正当化は、必然的に(宗教的あるいは道徳的な)深い形而上学的コミットメントに基づくものであり、それは合 理的に拒否されるものであるため、ロールズは、公的な政治的価値は個々の市民によってのみ私的に正当化されうるとした。公的なリベラル政治理念とそれに付 随する価値観は、(例えば司法意見や大統領演説の中で)公的に肯定されることはあっても、その深い正当性は肯定されない。正当化の仕事は、ロールズが「合 理的な包括的教義」と呼ぶものと、それを支持する市民に課される。合理的なカトリック教徒はある方法で、合理的なイスラム教徒は別の方法で、合理的な世俗 市民はさらに別の方法で、リベラルな価値観を正当化するだろう。ロールズの考えをベン図を使って説明することもできる。公的な政治的価値は、多数の合理的 な包括的教義が重なり合う共有空間となる。ロールズが『正義論』の中で提示した安定性に関する説明は、一つのカント的包括的教義と公正さとしての正義との 両立性を詳細に描いたものである。彼の望みは、他の多くの包括的教義についても同様の説明が提示されることである。これがロールズの有名な "重複するコンセンサス "という概念である。 このようなコンセンサスは、必然的にいくつかの教義、すなわち「不合理」な教義を除外することになる。不合理な包括的教義とは、礼節の義務と相容れないと いう意味で不合理なものである。これは別の言い方をすれば、不合理な教義は、リベラルな正義論が守るべき基本的な政治的価値(自由、平等、公正)と相容れ ないということである。では、このような教義についてロールズは何を言いたいのかという問いに対する一つの答えは、「何も言わない」である。というのも、 このような教義を正当化するような行為は、すでに述べたように、公的な政治的場から排除された道徳的・宗教的公約を論じることになるからである。しかし、 より重要なことは、ロールズ的プロジェクトの目的は、政治的正当性についてのリベラルな概念が内的に首尾一貫しているかどうかを判断することにあり、この プロジェクトは、リベラルな価値観にコミットする人々が、政治的な事柄について互いに対話し、審議し、議論する際に、どのような種類の理由を用いることが 許されるかを規定することによって遂行されるのである。ロールズのプロジェクトは、リベラルな価値観にまだコミットしていない人々、あるいは少なくともリ ベラルな価値観に心を開いていない人々に対して、リベラルな価値観を正当化することへの関心を排除して、この目標を掲げている。ロールズの関心は、礼節と 相互正当化の義務という観点から具体化された政治的正統性の概念が、現代の民主主義社会における宗教的・道徳的多元主義に直面したときに、実行可能な言論 形態として機能しうるかどうかにあるのであって、そもそもこの政治的正統性の概念を正当化することにあるのではない。 ロールズはまた、正義の原則を次のように修正した(第一の原則が第二の原則に優先し、第二の原則の前半が後半に優先する): 各人は、基本的権利と自由に関する完全に適切なスキームに対する平等な権利を有し、そのスキームは万人にとって同じスキームと両立する。このスキームにお いて、平等な政治的自由、そしてそれらの自由のみが、公正な価値を保証される。 社会的・経済的不平等は、2つの条件を満たすものでなければならない。第1に、公正な機会平等の条件の下で、万人に開かれた地位や役職に付随するものでな ければならない。第2に、社会の最も恵まれない構成員の最大の利益となるものでなければならない。 これらの原則は、『セオリー』の原則から微妙に変更されている。第一の原則は、「平等な権利」ではなく「平等な請求権」となり、「基本的自由の制度」とい う表現も「平等な基本的権利と自由の完全に十分な制度」に置き換えられている。第2原則の2つの部分も入れ替えられ、差異原則は3つの原則のうちの後者に なった。 人民法 主な記事 人民法 ロールズは『正義論』の中で国際情勢について一応の言及はしているが、国際政治について包括的な理論を打ち立てたのは『諸国民の法』の出版からである。彼 はそこで、「秩序ある」国民は「自由主義的」であるか「良識的」であるかのどちらかであると主張した。国際政治におけるロールズの基本的な違いは、国家間 の関係に基づく国際政治という従来の歴史的な議論とは別に、人民の社会を重視するという点である。 ロールズは、リベラルな国際秩序の正統性は、まともな人民を容認することが条件であると主張した。まともな人民とは、リベラルな人民とは異なる点として、 国教を持ち、少数派の信者が国家内で権力の座につく権利を否定したり、選挙ではなく協議の場を通じて政治参加を組織したりすることが挙げられる。しかし、 秩序ある民族が人権を侵害したり、対外的に攻撃的な振る舞いをしたりすることはない。リベラル」あるいは「良識ある」民族の基準を満たさない民族は、その 特殊な欠点に応じて、「無法国家」、「不利な条件を背負わされた社会」、あるいは「博愛絶対主義」と呼ばれる。そのような民族には、自由主義的で良識ある 民族が持つ相互尊重と寛容の権利はない。 この著作で表明されたロールズのグローバルな分配的正義に関する見解は、平等主義的リベラリスト仲間の多くを驚かせた。例えば、チャールズ・ベイツは以 前、ロールズの「差異原理」をグローバルに適用することを主張する研究を書いていた。ロールズは、世界国家は存在せず、安定しないという理由もあって、彼 の原則をそう適用することを否定した。この考え方は、ブレトン・ウッズ体制など、人類間の主要な社会財を分配する役割を果たす包括的なグローバル・ガバナ ンスのシステムが生まれたことにより、否定されるようになった。したがって、公正さとしての正義の理論のコスモポリタンな適用が、政治的強制力が行使され るすべての人に対してより正当であるため、「人民の法」の適用よりも合理的な代替案であると主張されてきた[29]。 しかしロールズによれば、国民国家は市民とは異なり、国内社会を構成する協同事業において自給自足していた。ロールズは、経済的な理由から人権を保護する ことができない政府に対して援助が行われるべきであると認識していたが、彼はこの援助の目的は最終的に世界的な平等状態を達成することではなく、むしろこ れらの社会が自由主義的あるいはまともな政治制度を維持できるようにすることであると主張していた。特に彼は、援助を無制限に続けることは、勤勉な国民を 持つ国が怠惰な国民を持つ国に補助金を与えることになり、政府が責任ある支出をした国から救済されることを知りながら無責任な支出をするモラルハザードの 問題を引き起こすと主張した。 一方、ロールズの「非理想」論には、民間人への爆撃や、第二次世界大戦におけるアメリカによるドイツや日本の都市への爆撃の非難、移民や核拡散についての 議論が含まれている。また、国内から大きな圧力がかかっても、次世代に目を向け、国際協調を推進する政治指導者、ステーツマンの理想像についても詳述して いる。ロールズはまた、人権侵害は侵害国への軍事介入を正当化しうると主張し、物議をかもしたが、彼はまた、そのような社会が自由で良識ある人々の良い模 範によって平和的に改革されるように誘導されることへの期待も表明した。 |

| Influence and reception See also: Original position § Criticisms Despite the exacting, academic tone of Rawls's writing and his reclusive personality, his philosophical work has exerted an enormous impact on not only contemporary moral and political philosophy but also public political discourse. During the student protests at Tiananmen Square in 1989, copies of "A Theory of Justice" were brandished by protesters in the face of government officials.[30][31][32] Despite being approximately 600 pages long, over 300,000 copies of that book have been sold,[33] stimulating critical responses from utilitarian, feminist, conservative, libertarian, Catholic, communitarian, Marxist and Green scholars. Although having a profound influence on theories of distributive justice both in theory and in practice, the generally anti-meritocratic sentiment of Rawls's thinking has not been widely accepted by the political left. He consistently held the view that naturally developed skills and endowments could not be neatly distinguished from inherited ones, and that neither could be used to justify moral desert.[34] Instead, he held the view that individuals could "legitimately expect" entitlements to the earning of income or development of abilities based on institutional arrangements. This aspect of Rawls's work has been instrumental in the development of such ideas as luck egalitarianism and unconditional basic income, which have themselves been criticized.[35][36] The strictly egalitarian quality of Rawls's second principle of justice has called into question the type of equality that fair societies ought to embody.[37][38] In a 2008 national survey of political theorists, based on 1,086 responses from professors at accredited, four-year colleges and universities in the United States, Rawls was voted first on the list of "Scholars Who Have Had the Greatest Impact on Political Theory in the Past 20 Years".[10] Communitarian critique Charles Taylor, Alasdair Macintyre, Michael Sandel, and Michael Walzer produced a range of critical responses contesting the universalist basis of Rawls' original position. While these criticisms, which emphasize the cultural and social roots of normative political principles, are typically described as communitarian critiques of Rawlsian liberalism, none of their authors identified with philosophical communitarianism. In his later works, Rawls attempted to reconcile his theory of justice with the possibility that its normative foundations may not be universally applicable.[39] September Group The late philosopher G. A. Cohen, along with political scientist Jon Elster, and John Roemer, used Rawls's writings extensively to inaugurate the Analytical Marxism movement in the 1980s. Frankfurt School In the later part of Rawl's career, he engaged with the scholarly work of Jürgen Habermas (see Habermas-Rawls debate). Habermas's reading of Rawls led to an appreciation of Rawls's work and other analytical philosophers by the Frankfurt School of critical theory, and many of Habermas's own students and associates were expected to be familiar with Rawls by the late 1980s.[40] The Leibniz Prize-winning political philosopher Rainer Forst was advised by both by Rawls and Habermas in completing his PhD.[41][42] Axel Honneth, Fabian Freyenhagen, and James Gordon Finlayson have also drawn on Rawls's work in comparison to Habermas. Feminist political philosophy Philosopher Eva Kittay has extended the work of John Rawls to address the concerns of women and cognitively disabled people.[43] |

影響力と受容 こちらも参照: 独自の立場 § 批判 ロールズの著述は厳密でアカデミックな論調であり、また隠遁的な性格であったにもかかわらず、彼の哲学的著作は現代の道徳哲学や政治哲学だけでなく、公の 政治的言説にも多大な影響を及ぼしている。1989年の天安門事件では、『正義論』がデモ隊によって政府高官に向かって振り回された[30][31] [32]。約600ページにもかかわらず、同書は30万部以上販売され[33]、功利主義者、フェミニスト、保守主義者、リバタリアン、カトリック、共同 体主義者、マルクス主義者、グリーン派の学者たちから批判的な反響を呼んだ。 理論と実践の両面において分配的正義の理論に多大な影響を与えたが、ロールズの考え方は一般的に反実力主義的であるため、政治的左派には広く受け入れられ ていない。彼は一貫して、生まれながらにして培われた能力や素養は遺伝的なものときれいに区別することはできず、どちらも道徳的な砂漠を正当化するために 用いることはできないという見解を有していた[34]。その代わりに、彼は制度的な取り決めに基づき、個人が収入を得たり能力を伸ばしたりする権利を「正 当に期待する」ことができるという見解を有していた。ロールズの著作のこの側面は、運の平等主義や無条件ベーシックインカムといった考え方の発展に役立っ ているが、それ自体批判されている[35][36]。ロールズの正義の第二原則の厳格な平等主義的性質は、公正な社会が具現化すべき平等のタイプに疑問を 投げかけている[37][38]。 2008年に行われた政治理論家の全国調査において、アメリカ国内の4年制大学の教授からの1,086の回答に基づき、ロールズは「過去20年間で政治理 論に最も大きな影響を与えた学者」のリストの1位に選ばれた[10]。 コミュニタリアン批判 チャールズ・テイラー、アラスデア・マッキンタイア、マイケル・サンデル、マイケル・ウォルツァーは、ロールズの当初の立場の普遍主義的基礎に異議を唱え る様々な批判的反応を生み出した。規範的な政治原理の文化的・社会的根源を強調するこれらの批判は、一般的にロールズ的自由主義に対する共同体主義的批判 として説明されるが、その著者の誰一人として哲学的共同体主義とは同一視していない。後年の著作において、ロールズはその規範的基礎が普遍的に適用される ものではない可能性と自身の正義の理論を調和させようと試みている[39]。 セプテンバー・グループ 哲学者の故G.A.コーエンは、政治学者のジョン・エルスター、ジョン・ローマーとともに、ロールズの著作を多用し、1980年代に分析的マルクス主義運 動を発足させた。 フランクフルト学派 ロールのキャリアの後期には、ユルゲン・ハーバーマスの学術的研究に関与した(ハーバーマスとロールの論争を参照)。ハーバーマスがロールズを読んだこと で、批評理論のフランクフルト学派がロールズの著作や他の分析哲学者を評価するようになり、1980年代後半にはハーバーマス自身の学生や仲間の多くが ロールズに精通していることが予想された。 [ライプニッツ賞を受賞した政治哲学者のライナー・フォルストは博士号を取得する際にロールズとハーバーマスの両方から助言を受けた[41][42]。 フェミニスト政治哲学 哲学者のエヴァ・キッテイは、ジョン・ロールズの研究を拡張し、女性や認知障害者の懸念を取り上げている[43]。 |

| Awards and honors Bronze Star for radio work behind enemy lines in World War II[44] Elected to the American Academy of Arts and Sciences (1966)[45] Ralph Waldo Emerson Award (1972) Elected to the American Philosophical Society (1974)[46] Member of the Norwegian Academy of Science and Letters (1992)[47] Schock Prize for Logic and Philosophy (1999) National Humanities Medal (1999) Asteroid 16561 Rawls is named in his honor. |

受賞歴と栄誉 第二次世界大戦における敵後方での無線活動によるブロンズスター章[44] アメリカ芸術科学アカデミー会員選出(1966年)[45] ラルフ・ワルド・エマーソン賞(1972年) アメリカ哲学会会員選出(1974年)[46] ノルウェー科学文学アカデミー会員(1992年)[47] ショック賞(論理学・哲学部門)(1999年) 全米人文科学メダル(1999年) 小惑星16561ロールズは彼の名誉を称えて命名された。 |

| In popular culture John Rawls is featured as the protagonist of A Theory of Justice: The Musical!, an award-nominated musical comedy, which premiered at Oxford in 2013 and was revived for the Edinburgh Fringe Festival.[48] |

大衆文化 ジョン・ロールズは『正義論』の主人公として登場する: 2013年にオックスフォードで初演され、エジンバラ・フリンジ・フェスティバルで再演されたミュージカル・コメディで、数々の賞にノミネートされている [48]。 |

| Bibliography A Study in the Grounds of Ethical Knowledge: Considered with Reference to Judgments on the Moral Worth of Character. Ph.D. dissertation, Princeton University, 1950. A Theory of Justice. Cambridge, Massachusetts: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 1971. The revised edition of 1999 incorporates changes that Rawls made for translated editions of A Theory of Justice. Some Rawls scholars use the abbreviation TJ to refer to this work. Political Liberalism. The John Dewey Essays in Philosophy, 4. New York: Columbia University Press, 1993. The hardback edition published in 1993 is not identical. The paperback adds a valuable new introduction and an essay titled "Reply to Habermas." Some Rawls scholars use the abbreviation PL to refer to this work. The Law of Peoples: with "The Idea of Public Reason Revisited." Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 1999. This slim book includes two works; a further development of his essay entitled "The Law of Peoples" and another entitled "Public Reason Revisited," both published earlier in his career. Collected Papers. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 1999. This collection of shorter papers was edited by Samuel Freeman. Lectures on the History of Moral Philosophy. Cambridge, Massachusetts, Harvard University Press, 2000. This collection of lectures was edited by Barbara Herman. It has an introduction on modern moral philosophy from 1600 to 1800 and then lectures on Hume, Leibniz, Kant and Hegel. Justice as Fairness: A Restatement. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Belknap Press, 2001. This shorter summary of the main arguments of Rawls's political philosophy was edited by Erin Kelly. Many versions of this were circulated in typescript and much of the material was delivered by Rawls in lectures when he taught courses covering his own work at Harvard University. Lectures on the History of Political Philosophy. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 2007. Collection of lectures on Thomas Hobbes, John Locke, Joseph Butler, Jean-Jacques Rousseau, David Hume, John Stuart Mill and Karl Marx, edited by Samuel Freeman. A Brief Inquiry into the Meaning of Sin and Faith. Cambridge, Massachusetts, Harvard University Press, 2010. With introduction and commentary by Thomas Nagel, Joshua Cohen and Robert Merrihew Adams. Senior thesis, Princeton, 1942. This volume includes a brief late essay by Rawls entitled On My Religion. Articles "Outline of a Decision Procedure for Ethics." Philosophical Review (April 1951), 60 (2): 177–197. "Two Concepts of Rules." Philosophical Review (January 1955), 64 (1):3–32. "Justice as Fairness." Journal of Philosophy (October 24, 1957), 54 (22): 653–362. "Justice as Fairness." Philosophical Review (April 1958), 67 (2): 164–194. "The Sense of Justice." Philosophical Review (July 1963), 72 (3): 281–305. "Constitutional Liberty and the Concept of Justice" Nomos VI (1963) "Distributive Justice: Some Addenda." Natural Law Forum (1968), 13: 51–71. "Reply to Lyons and Teitelman." Journal of Philosophy (October 5, 1972), 69 (18): 556–557. "Reply to Alexander and Musgrave." Quarterly Journal of Economics (November 1974), 88 (4): 633–655. "Some Reasons for the Maximin Criterion." American Economic Review (May 1974), 64 (2): 141–146. "Fairness to Goodness." Philosophical Review (October 1975), 84 (4): 536–554. "The Independence of Moral Theory." Proceedings and Addresses of the American Philosophical Association (November 1975), 48: 5–22. "A Kantian Conception of Equality." Cambridge Review (February 1975), 96 (2225): 94–99. "The Basic Structure as Subject." American Philosophical Quarterly (April 1977), 14 (2): 159–165. "Kantian Constructivism in Moral Theory." Journal of Philosophy (September 1980), 77 (9): 515–572. "Justice as Fairness: Political not Metaphysical." Philosophy & Public Affairs (Summer 1985), 14 (3): 223–251. "The Idea of an Overlapping Consensus." Oxford Journal for Legal Studies (Spring 1987), 7 (1): 1–25. "The Priority of Right and Ideas of the Good." Philosophy & Public Affairs (Fall 1988), 17 (4): 251–276. "The Domain of the Political and Overlapping Consensus." New York University Law Review (May 1989), 64 (2): 233–255. "Roderick Firth: His Life and Work." Philosophy and Phenomenological Research (March 1991), 51 (1): 109–118. "The Law of Peoples." Critical Inquiry (Fall 1993), 20 (1): 36–68. "Political Liberalism: Reply to Habermas." Journal of Philosophy (March 1995), 92 (3):132–180. "The Idea of Public Reason Revisited." Chicago Law Review (1997), 64 (3): 765–807. [PRR] Book chapters "Constitutional Liberty and the Concept of Justice." In Carl J. Friedrich and John W. Chapman, eds., Nomos, VI: Justice, pp. 98–125. Yearbook of the American Society for Political and Legal Philosophy. New York: Atherton Press, 1963. "Legal Obligation and the Duty of Fair Play." In Sidney Hook, ed., Law and Philosophy: A Symposium, pp. 3–18. New York: New York University Press, 1964. Proceedings of the 6th Annual New York University Institute of Philosophy. "Distributive Justice." In Peter Laslett and W. G. Runciman, eds., Philosophy, Politics, and Society. Third Series, pp. 58–82. London: Blackwell; New York: Barnes & Noble, 1967. "The Justification of Civil Disobedience." In Hugo Adam Bedau, ed., Civil Disobedience: Theory and Practice, pp. 240–255. New York: Pegasus Books, 1969. "Justice as Reciprocity." In Samuel Gorovitz, ed., Utilitarianism: John Stuart Mill: With Critical Essays, pp. 242–268. New York: Bobbs-Merrill, 1971. "Author's Note." In Thomas Schwartz, ed., Freedom and Authority: An Introduction to Social and Political Philosophy, p. 260. Encino & Belmont, California: Dickenson, 1973. "Distributive Justice." In Edmund S. Phelps, ed., Economic Justice: Selected Readings, pp. 319–362. Penguin Modern Economics Readings. Harmondsworth & Baltimore: Penguin Books, 1973. "Personal Communication, January 31, 1976." In Thomas Nagel's "The Justification of Equality." Critica (April 1978), 10 (28): 9n4. "The Basic Liberties and Their Priority." In Sterling M. McMurrin, ed., The Tanner Lectures on Human Values, III (1982), pp. 1–87. Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press; Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1982. "Social unity and primary goods" in Sen, Amartya; Williams, Bernard, eds. (1982). Utilitarianism and beyond. Cambridge / Paris: Cambridge University Press / Editions de la Maison des Sciences de l'Homme. pp. 159–185. ISBN 978-0511611964. "Themes in Kant's Moral Philosophy." In Eckhart Forster, ed., Kant's Transcendental Deductions: The Three Critiques and the Opus postumum, pp. 81–113, 253–256. Stanford Series in Philosophy. Studies in Kant and German Idealism. Stanford, California: Stanford University Press, 1989. Reviews Review of Axel Hägerström's Inquiries into the Nature of Law and Morals (C.D. Broad, tr.). Mind (July 1955), 64 (255):421–422. Review of Stephen Toulmin's An Examination of the Place of Reason in Ethics (1950). Philosophical Review (October 1951), 60 (4): 572–580. Review of A. Vilhelm Lundstedt's Legal Thinking Revised. Cornell Law Quarterly (1959), 44: 169. Review of Raymond Klibansky, ed., Philosophy in Mid-Century: A Survey. Philosophical Review (January 1961), 70 (1): 131–132. Review of Richard B. Brandt, ed., Social Justice (1962). Philosophical Review (July 1965), 74(3): 406–409. |

参考文献 倫理的知識の根拠に関する研究:性格の道徳的価値に関する判断を参照して考察する。プリンストン大学博士論文、1950年。 正義論。マサチューセッツ州ケンブリッジ:ハーバード大学出版局ベルナップ・プレス、1971年。1999年の改訂版には、正義論の翻訳版向けにロールズが行った変更が反映されている。一部のロールズ研究者はこの著作を指すのにTJという略称を用いる。 『政治的自由主義』。ジョン・デューイ哲学論文集第4巻。ニューヨーク:コロンビア大学出版局、1993年。1993年刊行のハードカバー版は同一ではな い。ペーパーバック版には貴重な新たな序文と「ハーバーマスへの返答」と題する論文が追加されている。一部のロールズ研究者はこの著作を指すのにPLとい う略称を用いる。 『人々の人格:公共的理性の理念再考』マサチューセッツ州ケンブリッジ:ハーバード大学出版局、1999年。この薄い書籍には二つの著作が含まれる。彼の初期の著作である「人々の人格」と「公共的理性の理念再考」のさらなる発展形である。 『論文集』マサチューセッツ州ケンブリッジ:ハーバード大学出版局、1999年。この短編論文集はサミュエル・フリーマンが編集した。 『道徳哲学史講義』マサチューセッツ州ケンブリッジ:ハーバード大学出版局、2000年。この講義録はバーバラ・ハーマンが編集した。1600年から 1800年までの近代道徳哲学に関する序論に続き、ヒューム、ライプニッツ、カント、ヘーゲルに関する講義が収録されている。 『正義とは公正である:再述』 マサチューセッツ州ケンブリッジ:ベルナップ・プレス、2001年。この短い要約は、ロールズの政治哲学の主要な議論をまとめたもので、エリン・ケリーが 編集した。この要約の多くのバージョンがタイプ原稿で流通し、その内容の多くは、ロールズがハーバード大学で自身の著作を扱う講義を行った際に講義として 発表されたものである。 政治哲学史講義。マサチューセッツ州ケンブリッジ:ハーバード大学出版局、2007年。トマス・ホッブズ、ジョン・ロック、ジョセフ・バトラー、ジャン= ジャック・ルソー、デイヴィッド・ヒューム、ジョン・スチュアート・ミル、カール・マルクスに関する講義集。サミュエル・フリーマン編。 『罪と信仰の意味に関する簡潔な考察』。マサチューセッツ州ケンブリッジ:ハーバード大学出版局、2010年。トマス・ネーゲル、ジョシュア・コーエン、 ロバート・メリヒュー・アダムズによる序文と解説付き。プリンストン大学卒業論文、1942年。本書にはロールズによる晩年の短編『私の宗教について』が 収録されている。 論文 「倫理のための決定手続きの概説」『フィロソフィカル・レビュー』(1951年4月)、60巻2号:177–197頁。 「規則の二つの概念」『フィロソフィカル・レビュー』(1955年1月)、64巻1号:3–32頁。 「公正としての正義」『哲学ジャーナル』(1957年10月24日)、54巻22号:653–362頁。 「公正としての正義」『フィロソフィカル・レビュー』(1958年4月)、67巻2号:164–194頁。 「正義の感覚」『フィロソフィカル・レビュー』(1963年7月)、72巻3号:281–305頁。 「憲法上の自由と正義の概念」『ノモス』VI巻(1963年) 「分配的正義:補遺」『ナチュラル・ロー・フォーラム』(1968年)、13号:51–71頁。 「ライアンズとタイテルマンへの返答」『哲学ジャーナル』(1972年10月5日)、69巻18号:556–557頁。 「アレクサンダーとマスグレイブへの返答」『クォータリー・ジャーナル・オブ・エコノミクス』(1974年11月)、88巻4号:633–655頁。 「最大最小基準のいくつかの根拠」『アメリカ経済評論』(1974年5月)、64巻2号:141–146頁。 「善への公平性」『哲学評論』(1975年10月)、84巻4号:536–554頁。 「道徳理論の独立性」『アメリカ哲学協会会議録・講演録』(1975年11月)、48: 5–22頁。 「平等に関するカント的構想」『ケンブリッジ・レビュー』(1975年2月)、96巻2225号: 94–99頁。 「主体としての基本構造」『アメリカ哲学季刊』(1977年4月)、14巻2号:159–165頁。 「道徳理論におけるカント的構成主義」『哲学ジャーナル』(1980年9月)、77巻9号:515–572頁。 「公正としての正義:形而上学的ではなく政治的なもの」『哲学と公共問題』(1985年夏)、14巻3号:223–251頁。 「重なり合う合意の概念」『オックスフォード法律研究ジャーナル』(1987年春)、7巻1号:1–25頁。 「権利の優先性と善の理念」『哲学と公共問題』(1988年秋)、17巻4号:251–276頁。 「政治の領域と重なり合う合意」『ニューヨーク大学法律評論』(1989年5月)、64巻2号:233–255頁。 「ロデリック・ファース:その生涯と業績」『哲学と現象学研究』(1991年3月)、51巻1号:109–118頁。 「人民の法」『クリティカル・インクワイアリー』(1993年秋)、20巻1号:36–68頁。 「政治的自由主義:ハーバーマスへの返答」『哲学ジャーナル』(1995年3月)、92巻3号:132–180頁。 「公共的理性の概念再考」『シカゴ・ロー・レビュー』(1997年)、64巻3号:765–807頁。[PRR] 書籍の章 「憲法上の自由と正義の概念」カール・J・フリードリヒ、ジョン・W・チャップマン編『ノモスVI:正義』所収、98–125頁。アメリカ政治法哲学協会年報。ニューヨーク:アサートン出版、1963年。 「法的義務と公正な処遇の義務」シドニー・フック編『法と哲学:シンポジウム』所収、3–18頁。ニューヨーク:ニューヨーク大学出版局、1964年。第6回ニューヨーク大学哲学研究所年次会議記録。 「分配的正義」ピーター・ラスレット、W・G・ランシマン編『哲学、政治、社会』第三シリーズ所収、58–82頁。ロンドン:ブラックウェル;ニューヨー ク:バーンズ・アンド・ノーブル、1967年。第三シリーズ、58–82頁。ロンドン:ブラックウェル;ニューヨーク:バーンズ・アンド・ノーブル、 1967年。 「市民的不服従の正当化」。ウーゴ・アダム・ベドー編『市民的不服従:理論と実践』、240–255頁。ニューヨーク:ペガサス・ブックス、1969年。 「正義としての互恵性」。サミュエル・ゴロヴィッツ編『功利主義:ジョン・スチュアート・ミル:批評的論考を付す』所収、242–268頁。ニューヨーク:ボブズ・メリル、1971年。 「著者注」。トーマス・シュワルツ編『自由と権威:社会・政治哲学入門』所収、260頁。カリフォルニア州エンシーノ&ベルモント:ディケンソン、1973年。 「分配的正義」エドマンド・S・フェルプス編『経済的正義:選集』319–362頁。ペンギン現代経済学選集。ハーモンズワース&ボルチモア:ペンギン・ブックス、1973年。 「個人通信、1976年1月31日」トーマス・ネーゲル『平等の正当化』所収。クリティカ(1978年4月)、10巻28号:9n4。 「基本的自由とその優先順位」。スターリング・M・マクマーリン編『人間価値に関するタナー講義III』(1982年)、1-87頁。ソルトレイクシティ:ユタ大学出版局;ケンブリッジ:ケンブリッジ大学出版局、1982年。 「社会的結束と一次的財」『功利主義とその先へ』アマルティア・セン、バーナード・ウィリアムズ編(1982年)。ケンブリッジ/パリ:ケンブリッジ大学 出版会/エディション・ド・ラ・メゾン・デ・サイエンス・ド・ロン。pp. 159–185。ISBN 978-0511611964。 「カント道徳哲学の主題」エックハルト・フォースター編『カントの超越論的演繹:三批判書とオプス・ポストゥヌム』所収、81–113頁、253–256 頁。スタンフォード哲学叢書。カントとドイツ観念論研究。カリフォルニア州スタンフォード:スタンフォード大学出版局、1989年。 書評 アクセル・ヘーゲルストローム著『法と道徳の本質に関する考察』(C.D.ブロード訳)の書評。『マインド』誌(1955年7月)、64巻255号:421–422頁。 スティーブン・トゥールミン著『倫理における理性の位置に関する考察』(1950年)の書評。Philosophical Review(1951年10月)、60巻4号:572–580頁。 A. ヴィルヘルム・ルンドステット著『法思考の再考』の書評。Cornell Law Quarterly(1959年)、44号:169頁。 レイモンド・クリバンスキー編『世紀半ばの哲学:概観』の書評。フィロソフィカル・レビュー(1961年1月)、70巻1号:131–132頁。 リチャード・B・ブラント編『社会正義』(1962年)の書評。フィロソフィカル・レビュー(1965年7月)、74巻3号:406–409頁。 |

| List of American philosophers List of liberal theorists Philosophy of economics A Theory of Justice: The Musical! |

アメリカの哲学者一覧 自由主義理論家のリスト 経済学の哲学 正義の理論 ミュージカル |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/John_Rawls |

|

A Theory of Justice

is a 1971 work of political philosophy and ethics by the philosopher

John Rawls (1921–2002) in which the author attempts to provide a moral

theory alternative to utilitarianism and that addresses the problem of

distributive justice (the socially just distribution of goods in a

society). The theory uses an updated form of Kantian philosophy and a

variant form of conventional social contract theory. Rawls's theory of

justice is fully a political theory of justice as opposed to other

forms of justice discussed in other disciplines and contexts. A Theory of Justice

is a 1971 work of political philosophy and ethics by the philosopher

John Rawls (1921–2002) in which the author attempts to provide a moral

theory alternative to utilitarianism and that addresses the problem of

distributive justice (the socially just distribution of goods in a

society). The theory uses an updated form of Kantian philosophy and a

variant form of conventional social contract theory. Rawls's theory of

justice is fully a political theory of justice as opposed to other

forms of justice discussed in other disciplines and contexts.The resultant theory was challenged and refined several times in the decades following its original publication in 1971. A significant reappraisal was published in the 1985 essay "Justice as Fairness" and the 2001 book Justice as Fairness: A Restatement in which Rawls further developed his two central principles for his discussion of justice. Together, they dictate that society should be structured so that the greatest possible amount of liberty is given to its members, limited only by the notion that the liberty of any one member shall not infringe upon that of any other member. Secondly, inequalities – either social or economic – are only to be allowed if the worst off will be better off than they might be under an equal distribution. Finally, if there is such a beneficial inequality, this inequality should not make it harder for those without resources to occupy positions of power – for instance, public office.[1] |

正

義の理論』は、哲学者ジョン・ロールズ(1921-2002)による1971年の政治哲学・倫理学の著作。この理論では、カント哲学と従来の社会契約説の

変形形式が用いられている。ロールズの正義論は、他の学問分野や文脈で論じられる他の正義の形態とは対照的に、完全に政治的な正義論である。 正

義の理論』は、哲学者ジョン・ロールズ(1921-2002)による1971年の政治哲学・倫理学の著作。この理論では、カント哲学と従来の社会契約説の

変形形式が用いられている。ロールズの正義論は、他の学問分野や文脈で論じられる他の正義の形態とは対照的に、完全に政治的な正義論である。その結果生まれた理論は、1971年に最初に発表されてから数十年の間に、何度も異議を唱えられ、改良された。重要な再評価は、1985年のエッセイ「公 正としての正義」と2001年の著書「公正としての正義」で発表された: その中でロールズは、正義を論じる上での2つの中心原則をさらに発展させた。この2つの原則はともに、社会はその構成員に可能な限り最大の自由が与えられ るように構成されるべきであり、その自由は他の構成員の自由を侵害してはならないという概念によってのみ制限されるべきであるというものである。第二に、 不平等が許されるのは、社会的であれ経済的であれ、平等な分配の下で、最も不利な立場にある人たちが、その人たちよりも有利になる場合に限られる。最後 に、このような有益な不平等がある場合、この不平等によって、資源のない人々が権力のある地位、例えば公職に就くことが難しくなってはならない[1]。 |

| Objective In A Theory of Justice, Rawls argues for a principled reconciliation of liberty and equality that is meant to apply to the basic structure of a well-ordered society.[2] Central to this effort is an account of the circumstances of justice, inspired by David Hume, and a fair choice situation for parties facing such circumstances, similar to some of Immanuel Kant's views. Principles of justice are sought to guide the conduct of the parties. These parties are recognized to face moderate scarcity, and they are neither naturally altruistic nor purely egoistic. They have ends which they seek to advance but prefer to advance them through cooperation with others on mutually acceptable terms. Rawls offers a model of a fair choice situation (the original position with its veil of ignorance) within which parties would hypothetically choose mutually acceptable principles of justice. Under such constraints, Rawls believes that parties would find his favoured principles of justice to be especially attractive, winning out over varied alternatives, including utilitarian and right-wing libertarian accounts. |

目的 ロールズは『正義論』の中で、秩序ある社会の基本構造に適用されることを意図した、自由と平等の原則的な調和を主張している[2]。この努力の中心は、デ イヴィッド・ヒュームに触発された正義の状況の説明と、イマヌエル・カントの見解の一部に類似した、そのような状況に直面する当事者の公正な選択状況であ る。正義の原則は、当事者の行動を導くために求められる。これらの当事者は適度な希少性に直面していることが認識されており、生来利他的でも純粋にエゴイ スティックでもない。彼らには前進させようとする目的があるが、相互に受け入れ可能な条件での他者との協力を通じてそれを前進させることを好む。ロールズは、当事者が仮に相互に受け入れ可能な正義の原則を選択するような公正な選択状況(無知のベールをかぶった本来の立場)のモデルを提示している。このような制約の下で、ロールズは、当事者は、自分が支持する正義の原理が特に魅力的であり、功利主義や右翼的なリバタリアンの説明など、様々な選択肢を凌駕すると考える。 |

| The "original position" Main article: Original position Rawls belongs to the social contract tradition, although he takes a different view from that of previous thinkers. Specifically, Rawls develops what he claims are principles of justice through the use of an artificial device he calls the Original position; in which, everyone decides principles of justice from behind a veil of ignorance. This "veil" is one that essentially blinds people to all facts about themselves so they cannot tailor principles to their own advantage: [N]o one knows his place in society, his class position or social status, nor does anyone know his fortune in the distribution of natural assets and abilities, his intelligence, strength, and the like. I shall even assume that the parties do not know their conceptions of the good or their special psychological propensities. The principles of justice are chosen behind a veil of ignorance. According to Rawls, ignorance of these details about oneself will lead to principles that are fair to all. If an individual does not know how he will end up in his own conceived society, he is likely not going to privilege any one class of people, but rather develop a scheme of justice that treats all fairly. In particular, Rawls claims that those in the Original Position would all adopt a maximin strategy which would maximize the prospects of the least well-off: They are the principles that rational and free persons concerned to further their own interests would accept in an initial position of equality as defining the fundamentals of the terms of their association.[3] Rawls bases his Original Position on a "thin theory of the good" which he says "explains the rationality underlying choice of principles in the Original Position". A full theory of the good follows after we derive principles from the original position. Rawls claims that the parties in the original position would adopt two such principles, which would then govern the assignment of rights and duties and regulate the distribution of social and economic advantages across society. The difference principle permits inequalities in the distribution of goods only if those inequalities benefit the worst-off members of society. Rawls believes that this principle would be a rational choice for the representatives in the original position for the following reason: Each member of society has an equal claim on their society's goods. Natural attributes should not affect this claim, so the basic right of any individual, before further considerations are taken into account, must be to an equal share in material wealth. What, then, could justify unequal distribution? Rawls argues that inequality is acceptable only if it is to the advantage of those who are worst-off. The agreement that stems from the original position is both hypothetical and ahistorical. It is hypothetical in the sense that the principles to be derived are what the parties would, under certain legitimating conditions, agree to, not what they have agreed to. Rawls seeks to use an argument that the principles of justice are what would be agreed upon if people were in the hypothetical situation of the original position and that those principles have moral weight as a result of that. It is ahistorical in the sense that it is not supposed that the agreement has ever been, or indeed could ever have been, derived in the real world outside of carefully limited experimental exercises. |

オリジナルポジション(原初的立場) 主な記事 本来の立場(原初的立場) ロールズは社会契約の伝統に属するが、それ以前の思想家とは異なる見解を持っている。具体的には、ロールズは、彼が「原初の立場」と呼ぶ人為的な装置を用いて、正義の原則と主張するものを展開する。この「ヴェール」とは、本質的に人々が自分自身に関するすべての事実を見えなくするものであり、そのため彼らは自分自身の有利になるように原則を調整することができない: [社会における自分の地位、階級的地位、社会的身分、生まれながらの資産や能力の分配における自分の幸運、自分の知力、体力などについては、誰も知らな い。私は、当事者が善に対する概念や特別な心理的傾向を知らないと仮定する。正義の原則は、無知のベールに包まれて選択される。 ロールズによれば、自分自身に関するこれらの詳細について無知であるこ とが、万人にとって公平な原則を導くという。もし個人が、自分の考える社会でどのような結末を迎えるかを知らなければ、特定の階級を優遇することはなく、 むしろすべての人を公平に扱う正義のスキームを開発する可能性が高い。特にロールズは、「原初の立場」にある者は皆、最も裕福でない者の見通しを最大化す るような最大公約数的な戦略を採用するだろうと主張する: それは、自らの利益を増進させることに関心を持つ合理的で自由な人々が、平等な最初の立場において、彼らの結社の条件の基本を定義するものとして受け入れるであろう原則である[3]。 ロールズは「原初的立場における原則の選択の根底にある合理性を説明する」とする「薄い善の理論」に彼の原初的立場を基づいている。完全な善の理論は、原初の立場から原理を導き出した後に導かれる。ロールズは、原立場の当事者はこのような2つの原則を採用し、それが権利と義務の割り当てを支配し、社会全体にわたる社会的・経済的利益の配分を規制するだろうと主張する。 差異原理は、財の分配における不平等が社会の最悪の構成員に利益をもたらす場合にのみ、その不平等を認めるものである。ロールズは、この原則は以下の理由 から、本来の立場の代表者にとって合理的な選択であると考える: 社会の各構成員は、その社会の財に対して平等な権利を有する。自然的属性はこの主張に影響を及ぼすべきではないので、さらなる考慮がなされる前に、あらゆ る個人の基本的権利は、物質的富の平等な分配でなければならない。では、不平等な分配を正当化できるものは何だろうか。ロールズは、不平等が容認されるの は、それが最も恵まれない人々にとって有利である場合に限られると主張する。 当初の立場に由来する合意は、仮説的かつ非歴史的である。導き出される原則は、当事者が合意したものではなく、一定の正当化条件のもとで合意するであろう ものであるという意味で、仮説的である。ロールズは、正義の原則は、人々が元の立場の仮想的状況にいたら合意されるものであり、その結果としてそれらの原 則は道徳的な重みを持つという議論を使おうとしている。注意深く限定された実験的な演習の外では、現実の世界でその合意が導き出されたことはないし、実際 に導き出される可能性もないという意味で、非歴史的である。 |

| The principles of justice Rawls modifies and develops the principles of justice throughout his book. In chapter forty-six, Rawls makes his final clarification on the two principles of justice: 1. Each person is to have an equal right to the most extensive total system of equal basic liberties compatible with a similar system of liberty for all.[4] 2. Social and economic inequalities are to be arranged so that they are both: (a) to the greatest benefit of the least advantaged, consistent with the just savings principle, and (b) attached to offices and positions open to all under conditions of fair equality of opportunity.[4] The first principle is often called the greatest equal liberty principle. Part (a) of the second principle is referred to as the difference principle while part (b) is referred to as the equal opportunity principle.[1] Rawls orders the principles of justice lexically, as follows: 1, 2b, 2a.[4] The greatest equal liberty principle takes priority, followed by the equal opportunity principle and finally the difference principle. The first principle must be satisfied before 2b, and 2b must be satisfied before 2a. As Rawls states: "A principle does not come into play until those previous to it are either fully met or do not apply."[5] Therefore, the equal basic liberties protected in the first principle cannot be traded or sacrificed for greater social advantages (granted by 2(b)) or greater economic advantages (granted by 2a).[6] The greatest equal liberty principle Each person is to have an equal right to the most extensive total system of equal basic liberties compatible with a similar system of liberty for all (1).[4] The greatest equal liberty principle is mainly concerned with the distribution of rights and liberties. Rawls identifies the following equal basic liberties: "political liberty (the right to vote and hold public office) and freedom of speech and assembly; liberty of conscience and freedom of thought; freedom of the person, which includes freedom from psychological oppression and physical assault and dismemberment (integrity of the person); the right to hold personal property and freedom from arbitrary arrest and seizure as defined by the concept of the rule of law."[7] It is a matter of some debate whether freedom of contract can be inferred to be included among these basic liberties: "liberties not on the list, for example, the right to own certain kinds of property and freedom of contract as understood by the doctrine of laissez-faire are not basic; and so they are not protected by the priority of the first principle.".[8] The difference principle Social and economic inequalities are to be arranged so that they are (a) to the greatest benefit of the least advantaged members of society, consistent with the just savings principle (2a).[4] Rawls' claim in (a) is that departures from equality of a list of what he calls primary goods—"things which a rational man wants whatever else he wants"[9] are justified only to the extent that they improve the lot of those who are worst-off under that distribution in comparison with the previous, equal, distribution. His position is at least in some sense egalitarian, with a provision that inequalities are allowed when they benefit the least advantaged. An important consequence of Rawls' view is that inequalities can actually be just, as long as they are to the benefit of the least well off. His argument for this position rests heavily on the claim that morally arbitrary factors (for example, the family one is born into) should not determine one's life chances or opportunities. Rawls is also oriented to an intuition that a person does not morally deserve their inborn talents; thus, that one is not entitled to all the benefits they could possibly receive from them; hence, at least one of the criteria which could provide an alternative to equality in assessing the justice of distributions is eliminated. Further, the just savings principle requires that some sort of material respect is left for future generations. Although Rawls is ambiguous about what this means, it can generally be understood as "a contribution to those coming later".[10] The equal opportunity principle Social and economic inequalities are to be arranged so that they are (b) attached to offices and positions open to all under conditions of fair equality of opportunity (2b).[4] The stipulation in 2b is lexically prior to that in 2a. This is because equal opportunity requires not merely that offices and positions are distributed on the basis of merit, but that all have reasonable opportunity to acquire the skills on the basis of which merit is assessed, even if one might not have the necessary material resources - due to a beneficial inequality stemming from the difference principle. It may be thought that this stipulation, and even the first principle of justice, may require greater equality than the difference principle, because large social and economic inequalities, even when they are to the advantage of the worst-off, will tend to seriously undermine the value of the political liberties and any measures towards fair equality of opportunity. |

正義の原理 ロールズは本書を通じて正義の原則を修正し、発展させている。第46章で、ロールズは正義の2つの原則について最終的な明確化を行う: 1. 1.各人は、万人のための同様の自由の体系と両立しうる、平等な基本的自由の最も広範な総体的体系に対する平等な権利を有する[4]。 2. 社会的・経済的不平等は、次のように整理されなければならない: (a)公正な貯蓄原則に合致するように、最も恵まれない人々の最大の利益となるように、また (b) 公平な機会均等の条件の下で、すべての人に開かれた地位や役職に就くこと[4]。 第一の原則は、しばしば最大平等自由原則と呼ばれる。第二原理の(a)の部分は差異原理と呼ばれ、(b)の部分は機会均等原理と呼ばれる[1]。 ロールズは正義の原理を次のように字句順に並べる: 1、2b、2a[4] 最大平等自由原則が優先され、機会均等原則がそれに続き、最後に差異原則が優先される。最初の原則は2bの前に満たされなければならず、2bは2aの前に 満たされなければならない。ロールズは次のように述べている: 「ある原則は、その前の原則が完全に満たされるか、あるいは適用されない限り、効力を発揮しない」[5]。したがって、第1原則で保護される平等な基本的 自由は、より大きな社会的利益(2(b)によって認められる)やより大きな経済的利益(2aによって認められる)のために交換されたり犠牲にされたりする ことはできない[6]。 最大の平等な自由の原則 各人は、万人のための同様の自由の制度と両立し得る最も広範な平等な基本的自由の総体的制度に対する平等な権利を有する(1)[4]。 最大平等自由原則は、主に権利と自由の分配に関するものである。ロールズは以下の平等な基本的自由を挙げている: 「政治的自由(投票権と公職に就く権利)と言論・集会の自由、良心の自由と思想の自由、心理的抑圧や身体的暴行・四肢切断からの自由を含む人身の自由(人 身の完全性)、個人財産を保有する権利、法の支配の概念によって定義される恣意的な逮捕・差押えからの自由」[7]。 契約の自由がこれらの基本的自由の中に含まれると推論できるかどうかは議論の余地がある: 「このリストにない自由、例えば、ある種の財産を所有する権利や、自由放任の教義によって理解される契約の自由は基本的なものではないので、第一原則の優 先順位によって保護されるものではない」[8]。 差異原理 社会的・経済的不平等は、公正貯蓄原則(2a)に合致するように、(a)社会の最も恵まれない構成員の最大の利益となるように調整されなければならない[4]。 ロールズの(a)の主張は、彼が一次財と呼ぶもののリスト-「合理的な人間が他に何を欲しがろうと欲するもの」[9]-の平等からの逸脱は、以前の平等な 分配と比較して、その分配の下で最も不利な立場にある人々の状況を改善する程度においてのみ正当化されるというものである。ロールズの立場は少なくともあ る意味では平等主義的であり、不平等が最も恵まれない者に利益をもたらす場合には許されるという規定がある。ロールズの見解の重要な帰結は、不平等が最も 恵まれない者の利益になる限り、実際には公正でありうるということである。この立場を主張するロールズの論拠は、道徳的に恣意的な要因(例えば、生まれた 家庭)によって人生のチャンスや機会が決定されるべきではないという主張に大きく依存している。ロールズはまた、人は道徳的に先天的に持って生まれた才能 に値しないという直観を志向している。したがって、人はその才能から受けられる可能性のある恩恵をすべて受ける権利があるわけではない。 さらに、公正貯蓄原則は、将来の世代のために何らかの物質的尊重を残すことを要求している。これが何を意味するかについてロールズは曖昧にしているが、一般的には「後に来る人々への貢献」と理解することができる[10]。 機会均等の原則 社会的・経済的不平等は、(b)公正な機会均等の条件の下で万人に開かれた地位や役職に付随するように整理されなければならない(2b)[4]。 2bの規定は、字句的には2aの規定に先立つものである。というのも、機会均等は、単に役職や地位が能力に基づいて分配されることを要求するだけでなく、 たとえ必要な物質的資源を有していなくても、差異原理から生じる有益な不平等によって、能力評価の基礎となる技能を習得する合理的な機会がすべての人に与 えられることを要求するからである。 というのも、社会的・経済的不平等が大きいと、たとえそれが最貧困層にとって有利なものであったとしても、政治的自由の価値や公正な機会平等のための措置が著しく損なわれる傾向があるからである。 |