animism

Five Ojibwe chiefs in the 19th century. It was anthropological studies of Ojibwe religion that resulted in the development of the "new animism".

animism

Five Ojibwe chiefs in the 19th century. It was anthropological studies of Ojibwe religion that resulted in the development of the "new animism".

解説:池田光穂

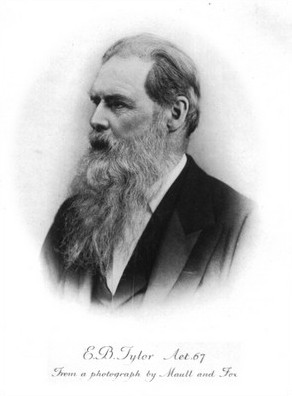

人類学におけるアニミズム(animism)は、19世紀の文化進化主義人類学者エドワー ド・B・タイラーが名付けたものが標準となっている。しかし彼の著書『未開文化(Primitive Culture)』においては、その語源は一七世紀のフロギストン派の化学者ゲオルグ・シュタールの生気論に由来すると述べている(Tylor 1903:425-426)。生気論は唯物論に対立する考え方で、あらゆる生命体はたんなる物質から成り立っているのではなく生命の「気(アニマ)」—— 魂とも訳されるが物理的な気体というよりも物質的な根拠をもたない生気のような概念である——が不可欠だとする思想である。アリストテレスの古典『霊魂 論』のラテン語のタイトルは「デ・アニマ(De anima, アニマ=魂について)」という。さてタイラーは、スピリチュアリズムがその代表だとしているが、アニミズムは——彼の言い方によると、いわゆるよ り古くか らの「低級の人類」から文明人のあいだにも見られる——普遍的な人間的特質と考えているようだ。タイラーによると、宗教はこのようなアニミズムみられる自 然崇拝から死者崇拝や呪物崇拝(フェティシズム)を経て多神教になり、そして最後に一神教へ進化したのではないかと考えた。ここでのポイントは、アニミズ ムは原始的な心性であるが、現代人にも共有するものだとしたことである。と言ってもタイラーが経験したのは一九世紀終わりから二〇世紀初頭が現代にほかな らないので、彼がいう現代人は、現在の我々が知るICTのテクノロジーからおよそほど遠い今から百年前の人びとであり、アニミニズムは彼らの心性であるこ とを押さえておこう。

| Animism

(from Latin: anima meaning 'breath, spirit, life')[1][2] is the belief

that objects, places, and creatures all possess a distinct spiritual

essence.[3][4][5][6] Animism perceives all things—animals, plants,

rocks, rivers, weather systems, human handiwork, and in some cases

words—as being animated, having agency and free will.[7] Animism is

used in anthropology of religion as a term for the belief system of

many Indigenous peoples[8] in contrast to the relatively more recent

development of organized religions.[9] Animism is a metaphysical belief

which focuses on the supernatural universe (beyond logical foundations

and procedures): specifically, on the concept of the immaterial

soul.[10] Although each culture has its own mythologies and rituals, animism is said to describe the most common, foundational thread of indigenous peoples' "spiritual" or "supernatural" perspectives. The animistic perspective is so widely held and inherent to most indigenous peoples that they often do not even have a word in their languages that corresponds to "animism" (or even "religion").[11] The term "animism" is an anthropological construct. Largely due to such ethnolinguistic and cultural discrepancies, opinions differ on whether animism refers to an ancestral mode of experience common to indigenous peoples around the world or to a full-fledged religion in its own right. The currently accepted definition of animism was only developed in the late 19th century (1871) by Edward Tylor. It is "one of anthropology's earliest concepts, if not the first."[12] Animism encompasses beliefs that all material phenomena have agency, that there exists no categorical distinction between the spiritual and physical world, and that soul, spirit, or sentience exists not only in humans but also in other animals, plants, rocks, geographic features (such as mountains and rivers), and other entities of the natural environment. Examples include water sprites, vegetation deities, and tree spirits, among others. Animism may further attribute a life force to abstract concepts such as words, true names, or metaphors in mythology. Some members of the non-tribal world also consider themselves animists, such as author Daniel Quinn, sculptor Lawson Oyekan, and many contemporary Pagans.[13] |

アニミズム(ラテン語で「息、精神、生命」を意味する

animaに由来する)[1][2]は、物体、場所、生物はすべて明確な精神的本質を持っているという信念である[3][4][5][6]。アニミズム

は、動物、植物、岩石、河川、気象システム、人間の手仕事、そして場合によっては言葉など、すべてのものが生気を帯び、主体性と自由意志を持っていると認

識している。

[7]アニミズムは宗教人類学において、組織化された宗教が比較的最近になって発展したのとは対照的に、多くの先住民の信仰体系を表す言葉として用いられ

ている[8]。[9]アニミズムは(論理的な基礎や手続きを超えた)超自然的な宇宙に焦点を当てた形而上学的な信仰であり、具体的には非物質的な魂の概念

に焦点を当てたものである[10]。 それぞれの文化には独自の神話や儀式があるが、アニミズムは先住民の「精神的」または「超自然的」な観点の最も一般的で基礎的な糸を表現していると言われ ている。アニミズム的な視点は、ほとんどの先住民に広く保持され、固有のものであるため、彼らの言語には「アニミズム」(あるいは「宗教」)に相当する言 葉すらないことが多い[11]。 アニミズムが世界中の先住民に共通する先祖伝来の経験様式を指すのか、それともそれ自体が本格的な宗教を指すのかについては、このような民族言語的・文化 的な相違のために意見が分かれている。現在受け入れられているアニミズムの定義は、エドワード・タイラーが19世紀後半(1871年)に提唱したものであ る。アニミズムは「人類学の最も初期の概念のひとつである。 アニミズムは、すべての物質的現象には作用があり、精神世界と物理的世界の間にカテゴリー的な区別は存在せず、魂、精神、または感覚は人間だけでなく、他 の動物、植物、岩石、地理的特徴(山や川など)、および自然環境の他のエンティティにも存在するという信念を包含している。例えば、水の精、植生の神、木 の精などである。アニミズムはさらに、神話に登場する言葉や真名、比喩などの抽象的な概念に生命力を与えることもある。作家のダニエル・クイン、彫刻家の ローソン・オイカン、現代の異教徒の多く[13]など、部族以外の世界にもアニミストを自認する者がいる。 |

| Etymology English anthropologist Sir Edward Tylor initially wanted to describe the phenomenon as spiritualism, but he realized that it would cause confusion with the modern religion of spiritualism, which was then prevalent across Western nations.[14] He adopted the term animism from the writings of German scientist Georg Ernst Stahl,[15] who had developed the term animismus in 1708 as a biological theory that souls formed the vital principle, and that the normal phenomena of life and the abnormal phenomena of disease could be traced to spiritual causes.[16] The origin of the word comes from the Latin word anima, which means life or soul.[17] The first known usage in English appeared in 1819.[18] |

語源 イギリスの人類学者であるエドワード・タイラー卿は当初、この現象をスピリチュアリズムと表現しようとしていたが、当時西洋諸国に広まっていたスピリチュ アリズムという近代宗教との混同を引き起こすことに気づいた[14]。 彼は、魂が生命原理(vital principle)を形成しており、生命の正常な現象や病気の異常な現象は霊的な原因にたどり着くことができるという生物学的理論として、1708年に ア ニミズムスという用語を開発したドイツの科学者ゲオルク・エルンスト・シュタール[15]の著作からアニミズムスという用語を採用した[16]。 語源は生命や魂を意味するラテン語のanimaに由来する[17]。 英語での最初の既知の用法は1819年に登場した[18]。 |

| "Old animism" definitions Earlier anthropological perspectives, which have since been termed the old animism, were concerned with knowledge on what is alive and what factors make something alive.[19] The old animism assumed that animists were individuals who were unable to understand the difference between persons and things.[20] Critics of the old animism have accused it of preserving "colonialist and dualistic worldviews and rhetoric."[21] Edward Tylor's definition  Edward Tylor developed animism as an anthropological theory. The idea of animism was developed by anthropologist Sir Edward Tylor through his 1871 book Primitive Culture,[1] in which he defined it as "the general doctrine of souls and other spiritual beings in general." According to Tylor, animism often includes "an idea of pervading life and will in nature;"[22] a belief that natural objects other than humans have souls. This formulation was little different from that proposed by Auguste Comte as "fetishism",[23] but the terms now have distinct meanings. For Tylor, animism represented the earliest form of religion, being situated within an evolutionary framework of religion that has developed in stages and which will ultimately lead to humanity rejecting religion altogether in favor of scientific rationality.[24] Thus, for Tylor, animism was fundamentally seen as a mistake, a basic error from which all religions grew.[24] He did not believe that animism was inherently illogical, but he suggested that it arose from early humans' dreams and visions and thus was a rational system. However, it was based on erroneous, unscientific observations about the nature of reality.[25] Stringer notes that his reading of Primitive Culture led him to believe that Tylor was far more sympathetic in regard to "primitive" populations than many of his contemporaries and that Tylor expressed no belief that there was any difference between the intellectual capabilities of "savage" people and Westerners.[4] The idea that there had once been "one universal form of primitive religion" (whether labelled animism, totemism, or shamanism) has been dismissed as "unsophisticated" and "erroneous" by archaeologist Timothy Insoll, who stated that "it removes complexity, a precondition of religion now, in all its variants."[26] Social evolutionist conceptions Tylor's definition of animism was part of a growing international debate on the nature of "primitive society" by lawyers, theologians, and philologists. The debate defined the field of research of a new science: anthropology. By the end of the 19th century, an orthodoxy on "primitive society" had emerged, but few anthropologists still would accept that definition. The "19th-century armchair anthropologists" argued that "primitive society" (an evolutionary category) was ordered by kinship and divided into exogamous descent groups related by a series of marriage exchanges. Their religion was animism, the belief that natural species and objects had souls. With the development of private property, the descent groups were displaced by the emergence of the territorial state. These rituals and beliefs eventually evolved over time into the vast array of "developed" religions. According to Tylor, as society became more scientifically advanced, fewer members of that society would believe in animism. However, any remnant ideologies of souls or spirits, to Tylor, represented "survivals" of the original animism of early humanity.[27] The term ["animism"] clearly began as an expression of a nest of insulting approaches to indigenous peoples and the earliest putatively religious humans. It was and sometimes remains, a colonialist slur.—Graham Harvey, 2005.[28] Confounding animism with totemism In 1869 (three years after Tylor proposed his definition of animism), Edinburgh lawyer John Ferguson McLennan, argued that the animistic thinking evident in fetishism gave rise to a religion he named totemism. Primitive people believed, he argued, that they were descended from the same species as their totemic animal.[23] Subsequent debate by the "armchair anthropologists" (including J. J. Bachofen, Émile Durkheim, and Sigmund Freud) remained focused on totemism rather than animism, with few directly challenging Tylor's definition. Anthropologists "have commonly avoided the issue of animism and even the term itself, rather than revisit this prevalent notion in light of their new and rich ethnographies."[29] According to anthropologist Tim Ingold, animism shares similarities with totemism but differs in its focus on individual spirit beings which help to perpetuate life, whereas totemism more typically holds that there is a primary source, such as the land itself or the ancestors, who provide the basis to life. Certain indigenous religious groups such as the Australian Aboriginals are more typically totemic in their worldview, whereas others like the Inuit are more typically animistic.[30] From his studies into child development, Jean Piaget suggested that children were born with an innate animist worldview in which they anthropomorphized inanimate objects and that it was only later that they grew out of this belief.[31] Conversely, from her ethnographic research, Margaret Mead argued the opposite, believing that children were not born with an animist worldview but that they became acculturated to such beliefs as they were educated by their society.[31] Stewart Guthrie saw animism—or "attribution" as he preferred it—as an evolutionary strategy to aid survival. He argued that both humans and other animal species view inanimate objects as potentially alive as a means of being constantly on guard against potential threats.[32] His suggested explanation, however, did not deal with the question of why such a belief became central to the religion.[33] In 2000, Guthrie suggested that the "most widespread" concept of animism was that it was the "attribution of spirits to natural phenomena such as stones and trees."[34] |

「古いアニミズム」の定義 古いアニミズムと呼ばれるようになった以前の人類学の視点は、何が生きているのか、どのような要因が何かを生かすのかについての知識に関係していた [19]。古いアニミズムはアニミストが人と物の違いを理解できない個人であると仮定していた[20]。 エドワード・タイラーの定義  エドワード・タイラーは人類学的理論としてアニミズムを発展させた。 アニミズムという考え方は、人類学者エドワード・タイラー卿が1871年に出版した『原始文化』[1]を通して発展させたものであり、その中で彼はアニミ ズムを "魂やその他の霊的存在全般に関する一般的な教義 "と定義している。タイラーによれば、アニミズムはしばしば「自然界に浸透する生命と意志の観念」[22]を含んでおり、人間以外の自然物には魂があると いう信念である。この定式化はオーギュスト・コントが「フェティシズム」として提唱したものとほとんど変わらなかったが[23]、現在ではこの用語は異な る意味を持つ。 タイラーにとってアニミズムは宗教の最も初期の形態を象徴するものであり、段階的に発展してきた宗教の進化の枠組みの中に位置づけられ、最終的に人類は科 学的合理性を支持して宗教を完全に拒絶することになる[24]。したがって、タイラーにとってアニミズムは基本的に誤りであり、すべての宗教がそこから発 展した基本的な誤りであると考えられていた[24]。しかし、それは現実の性質に関する誤った非科学的な観察に基づいていた[25]。ストリンガーは、 『原始文化』を読んだことで、タイラーが同時代の多くの人々よりも「原始的な」人々に対してはるかに同情的であり、タイラーは「未開人」と西洋人の知的能 力に差があるとは考えていなかったと述べている[4]。 アニミズム、トーテミズム、シャーマニズムのいずれであれ、「原始宗教の普遍的な一つの形」がかつて存在したという考え方は、考古学者のティモシー・イン ソルによって「素朴」かつ「誤り」として否定されており、彼は「現在の宗教の前提条件である複雑性を、そのすべての変種において取り除くものである」と述 べている[26]。 社会進化論的概念 タイラーのアニミズムの定義は、法律家、神学者、言語学者による「原始社会」の本質に関する国際的な議論の高まりの一部であった。この議論は、人類学とい う新しい科学の研究分野を定義した。19世紀末には「原始社会」に関する正統派が登場したが、その定義を受け入れる人類学者はまだほとんどいなかった。 19世紀のアームチェア人類学者」たちは、「原始社会」(進化論的カテゴリー)は親族関係によって秩序づけられ、一連の婚姻関係によって結びついた外戚関 係にある子孫集団に分かれていたと主張した。彼らの宗教はアニミズムであり、自然の種や物には魂があるという信仰であった。 私有財産の発展とともに、子孫集団は領土国家の出現によって姿を消した。これらの儀式や信仰はやがて、膨大な数の「発達した」宗教へと進化していった。タ イラーによれば、社会が科学的に進歩するにつれて、アニミズムを信じる者は少なくなっていった。しかし、魂や精霊に関するイデオロギーの残滓は、タイラー にとって、初期の人類が元々持っていたアニミズムの「生き残り」であった[27]。 アニミズム "という用語は明らかに、先住民や初期の宗教的な人間に対する侮辱的なアプローチの巣の表現として始まった。それは植民地主義的な中傷であったし、今でも そうである。-グレアム・ハーヴェイ、2005年[28]。 アニミズムとトーテミズムの混同 1869年(タイラーがアニミズムの定義を提唱した3年後)、エディンバラの弁護士ジョン・ファーガソン・マクレナンは、フェティシズムに見られるアニミ ズム的思考がトーテミズムと名付けた宗教を生み出したと主張した。J.J.バコッフェン、エミール・デュルケーム、ジークムント・フロイトを含む「腕利き の人類学者」たちによるその後の議論は、アニミズムよりもむしろトーテミズムに焦点が当てられ、タイラーの定義に直接異議を唱える者はほとんどいなかっ た。人類学者は「一般的に、新しく豊かな民族誌に照らしてこの一般的な概念を再検討するのではなく、アニミズムの問題、さらにはこの用語自体を避けてき た」[29]。 人類学者のティム・インゴールドによれば、アニミズムはトーテミズムと類似しているが、生命の永続を助ける個々の霊的存在に焦点を当てている点で異なって いる。オーストラリアのアボリジニのような特定の先住民の宗教集団は、より典型的なトーテミズム的世界観を持っているのに対し、イヌイットのような他の宗 教集団は、より典型的なアニミズム的世界観を持っている[30]。 ジャン・ピアジェは子どもの発達に関する研究から、子どもは生まれながらにして無生物を擬人化するアニミズム的な世界観を持っており、この信念から成長す るのは後になってからであると示唆した[31]。逆にマーガレット・ミードは民族誌的研究から、子どもは生まれながらにしてアニミズム的な世界観を持って いるのではなく、社会から教育を受けるにつれてそのような信念に馴化していくと考え、反対のことを主張した[31]。 スチュワート・ガスリーは、アニミズム(彼が好んだ「帰属」)を生存を助けるための進化戦略であると考えた。彼は、人間も他の動物種も、潜在的な脅威に対 して常に警戒する手段として、無生物を潜在的に生きているものとして見ていると主張した[32]。 しかし彼の提案した説明は、なぜそのような信仰が宗教の中心となったのかという疑問には対処していなかった[33]。 2000年にガスリーは、アニミズムの「最も広まった」概念は、「石や木などの自然現象に精霊を帰属させること」であると示唆した[34]。 |

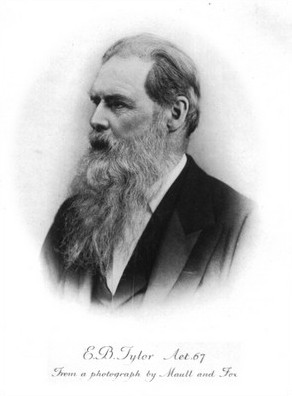

| "New animism" non-archaic

definitions Many anthropologists ceased using the term animism, deeming it to be too close to early anthropological theory and religious polemic.[21] However, the term had also been claimed by religious groups—namely, Indigenous communities and nature worshippers—who felt that it aptly described their own beliefs, and who in some cases actively identified as "animists."[35] It was thus readopted by various scholars, who began using the term in a different way,[21] placing the focus on knowing how to behave toward other beings, some of whom are not human.[19] As religious studies scholar Graham Harvey stated, while the "old animist" definition had been problematic, the term animism was nevertheless "of considerable value as a critical, academic term for a style of religious and cultural relating to the world."[36] Hallowell and the Ojibwe  Five Ojibwe chiefs in the 19th century. It was anthropological studies of Ojibwe religion that resulted in the development of the "new animism". The new animism emerged largely from the publications of anthropologist Irving Hallowell, produced on the basis of his ethnographic research among the Ojibwe communities of Canada in the mid-20th century.[37] For the Ojibwe encountered by Hallowell, personhood did not require human-likeness, but rather humans were perceived as being like other persons, who for instance included rock persons and bear persons.[38] For the Ojibwe, these persons were each willful beings, who gained meaning and power through their interactions with others; through respectfully interacting with other persons, they themselves learned to "act as a person".[38] Hallowell's approach to the understanding of Ojibwe personhood differed strongly from prior anthropological concepts of animism.[39] He emphasized the need to challenge the modernist, Western perspectives of what a person is, by entering into a dialogue with different worldwide views.[38] Hallowell's approach influenced the work of anthropologist Nurit Bird-David, who produced a scholarly article reassessing the idea of animism in 1999.[40] Seven comments from other academics were provided in the journal, debating Bird-David's ideas.[41] Postmodern anthropology More recently, postmodern anthropologists are increasingly engaging with the concept of animism. Modernism is characterized by a Cartesian subject-object dualism that divides the subjective from the objective, and culture from nature. In the modernist view, animism is the inverse of scientism, and hence, is deemed inherently invalid by some anthropologists. Drawing on the work of Bruno Latour, some anthropologists question modernist assumptions and theorize that all societies continue to "animate" the world around them. In contrast to Tylor's reasoning, however, this "animism" is considered to be more than just a remnant of primitive thought. More specifically, the "animism" of modernity is characterized by humanity's "professional subcultures", as in the ability to treat the world as a detached entity within a delimited sphere of activity. Human beings continue to create personal relationships with elements of the aforementioned objective world, such as pets, cars, or teddy bears, which are recognized as subjects. As such, these entities are "approached as communicative subjects rather than the inert objects perceived by modernists."[42] These approaches aim to avoid the modernist assumption that the environment consists of a physical world distinct from the world of humans, as well as the modernist conception of the person being composed dualistically of a body and a soul.[29] Nurit Bird-David argues that:[29] Positivistic ideas about the meaning of 'nature', 'life', and 'personhood' misdirected these previous attempts to understand the local concepts. Classical theoreticians (it is argued) attributed their own modernist ideas of self to 'primitive peoples' while asserting that the 'primitive peoples' read their idea of self into others! She explains that animism is a "relational epistemology" rather than a failure of primitive reasoning. That is, self-identity among animists is based on their relationships with others, rather than any distinctive features of the "self". Instead of focusing on the essentialized, modernist self (the "individual"), persons are viewed as bundles of social relationships ("dividuals"), some of which include "superpersons" (i.e. non-humans).  Animist altar, Bozo village, Mopti, Bandiagara, Mali, in 1972 Stewart Guthrie expressed criticism of Bird-David's attitude towards animism, believing that it promulgated the view that "the world is in large measure whatever our local imagination makes it." This, he felt, would result in anthropology abandoning "the scientific project."[43] Like Bird-David, Tim Ingold argues that animists do not see themselves as separate from their environment:[44] Hunter-gatherers do not, as a rule, approach their environment as an external world of nature that has to be 'grasped' intellectually … indeed the separation of mind and nature has no place in their thought and practice. Rane Willerslev extends the argument by noting that animists reject this Cartesian dualism and that the animist self identifies with the world, "feeling at once within and apart from it so that the two glide ceaselessly in and out of each other in a sealed circuit".[45] The animist hunter is thus aware of himself as a human hunter, but, through mimicry, is able to assume the viewpoint, senses, and sensibilities of his prey, to be one with it.[46] Shamanism, in this view, is an everyday attempt to influence spirits of ancestors and animals, by mirroring their behaviors, as the hunter does its prey. Ethical and ecological understanding Cultural ecologist and philosopher David Abram proposed an ethical and ecological understanding of animism, grounded in the phenomenology of sensory experience. In his books The Spell of the Sensuous and Becoming Animal, Abram suggests that material things are never entirely passive in our direct perceptual experience, holding rather that perceived things actively "solicit our attention" or "call our focus," coaxing the perceiving body into an ongoing participation with those things.[47][48] In the absence of intervening technologies, he suggests that sensory experience is inherently animistic in that it discloses a material field that is animate and self-organizing from the beginning. David Abram used contemporary cognitive and natural science, as well as the perspectival worldviews of diverse indigenous oral cultures, Abram proposed a richly pluralist and story-based cosmology in which matter is alive. He suggested that such a relational ontology is in close accord with humanity's spontaneous perceptual experience by drawing attention to the senses, and to the primacy of sensuous terrain, enjoining a more respectful and ethical relation to the more-than-human community of animals, plants, soils, mountains, waters, and weather-patterns that materially sustains humanity.[47][48] In contrast to a long-standing tendency in the Western social sciences, which commonly provide rational explanations of animistic experience, Abram develops an animistic account of reason itself. He holds that civilised reason is sustained only by intensely animistic participation between human beings and their own written signs. For instance, as soon as someone reads letters on a page or screen, they can "see what it says"—the letters speak as much as nature spoke to pre-literate peoples. Reading can usefully be understood as an intensely concentrated form of animism, one that effectively eclipses all of the other, older, more spontaneous forms of animistic participation in which humans were once engaged. To tell the story in this manner—to provide an animistic account of reason, rather than the other way around—is to imply that animism is the wider and more inclusive term and that oral, mimetic modes of experience still underlie, and support, all our literate and technological modes of reflection. When reflection's rootedness in such bodily, participatory modes of experience is entirely unacknowledged or unconscious, reflective reason becomes dysfunctional, unintentionally destroying the corporeal, sensuous world that sustains it.[49] Relation to the concept of 'I-thou' Religious studies scholar Graham Harvey defined animism as the belief "that the world is full of persons, only some of whom are human, and that life is always lived in relationship with others."[19] He added that it is therefore "concerned with learning how to be a good person in respectful relationships with other persons."[19] In his Handbook of Contemporary Animism (2013), Harvey identifies the animist perspective in line with Martin Buber's "I-thou" as opposed to "I-it". In such, Harvey says, the animist takes an I-thou approach to relating to the world, whereby objects and animals are treated as a "thou", rather than as an "it".[50] |

「新しいアニミズム」非アルカイックな定義 多くの人類学者は、アニミズムという用語は初期の人類学理論や宗教論争に近すぎるとしてその使用を中止した[21]。 「宗教学の学者であるグラハム・ハーヴェイが述べているように、「古いアニミスト」の定義には問題があったが、それでもアニミズムという用語は「世界と関 わる宗教的・文化的なスタイルに対する批判的で学術的な用語としてかなりの価値がある」[36]。 ハロウェルとオジブエ  19世紀、5人のオジブエ族長。「新しいアニミズム」の発展をもたらしたのは、オジブエの宗教に関する人類学的研究であった。 新しいアニミズムは主に人類学者アーヴィング・ハロウェルの出版物から生まれたもので、20世紀半ばにカナダのオジブウェ・コミュニティにおける彼の民族 誌的調査に基づいて作成された[37]。ハロウェルが出会ったオジブウェにとって、人間らしさは人間に似ていることを必要とせず、むしろ人間は他の人間に 似ているものとして認識されていた。 [38]オジブエにとって、これらの人物はそれぞれ意志を持った存在であり、他者との相互作用を通じて意味と力を得た。 ハロウェルのオジブウェ人としての理解へのアプローチは、アニミズムの先行する人類学的概念とは強く異なっていた[39]。 ハロウェルのアプローチは、1999年にアニミズムの考え方を再評価する学術論文を発表した人類学者ヌリット・バード=デヴィッドの研究に影響を与えた [40]。 ポストモダンの人類学 より最近では、ポストモダンの人類学者がアニミズムの概念との関わりを強めている。モダニズムの特徴は、主観と客観、文化と自然を分けるデカルト的な主観 と客観の二元論にある。モダニズムの見解では、アニミズムは科学主義の逆であり、それゆえ人類学者の中には本質的に無効であるとみなす者もいる。ブルー ノ・ラトゥールの研究に基づき、一部の人類学者はモダニズムの前提に疑問を投げかけ、すべての社会は自分たちを取り巻く世界を「生気づけ」続けていると理 論化している。しかし、タイラーの推論とは対照的に、この「アニミズム」は単なる原始思想の名残りではないと考えられている。より具体的に言えば、近代の 「アニミズム」は人類の「専門的サブカルチャー」によって特徴づけられており、それは、世界を限定された活動領域の中で切り離された存在として扱う能力に おいてである。 人間は、ペットや車、テディベアなど、前述の客観的世界の要素と個人的な関係を作り続け、それらは主体として認識される。これらのアプローチは、環境は人 間の世界とは異なる物理的な世界から構成されているというモダニズムの仮定や、人間は身体と魂の二元論的に構成されているというモダニズムの概念を回避す ることを目的としている[29]。 ヌリット・バード=デヴィッドは次のように論じている[29]。 「自然」、「生命」、「人格」の意味に関する実証主義的な考え方は、局所的な概念を理解しようとするこれらの以前の試みを誤った方向に導いた。古典的な理 論 家たちは、「原始人」が自己の観念を他者に読み込ませたと主張する一方で、彼ら自身の近代主義的な自己の観念を「原始人」に帰結させたと主張する! 彼女は、アニミズムは原始的な推論の失敗ではなく、「関係的認識論」であると説明する。つまり、アニミストの自己同一性は、「自己」のいかなる特徴より も、むしろ他者との関係に基づいている。本質化された近代主義的な自己(「個人」)に焦点を当てる代わりに、人は社会的関係の束(「ディデュアル」)とみ なされ、その中には「超人」(人間以外)も含まれる。  アニミストの祭壇(1972年、マリ、バンディアガラ州モプティ、ボゾ村 スチュワート・ガスリーは、バード=デイビッドのアニミズムに対する姿勢に批判を表明した。これは人類学が「科学的プロジェクト」を放棄することになると 彼は感じていた[43]。 バード=デイヴィッドと同様に、ティム・インゴルドもアニミストは自分たちを環境から切り離した存在だとは考えていないと主張している[44]。 狩猟採集民は原則として、自分たちの環境を知的に「把握」しなければならない外的な自然世界として捉えてはいない。 レイン・ウィラースレフは、アニミストはこのデカルト的な二元論を否定し、アニミストの自己は世界と同一化し、「世界の内と外を同時に感じ、両者は密閉さ れた回路を絶え間なく行き来する」のだと指摘し、この議論を拡張している。 [このようにアニミズムの狩人は、自分自身が人間の狩人であることを自覚しているが、擬態することによって獲物の視点、感覚、感性を想定し、獲物と一体化 することができる[46]。シャーマニズムは、狩人が獲物にするように、祖先や動物の行動を鏡のように映し出すことによって、霊魂に影響を与えようとする 日常的な試みである。 倫理的・生態学的理解 文化生態学者で哲学者のデイヴィッド・エイブラムは、感覚経験の現象学に基づいた、アニミズムの倫理的・生態学的理解を提唱した。エイブラムはその著書 『The Spell of the Sensuous(感覚的なものの呪縛)』と『Becoming Animal(動物になる)』の中で、物質的なものは私たちの直接的な知覚経験において決して完全に受動的なものではなく、むしろ知覚されたものは能動的 に「私たちの注意を促し」、あるいは「私たちの焦点を呼び」、知覚する身体をそれらのものへの継続的な参加へと誘うものであると示唆している[47] [48]。 介在する技術がない場合、感覚的な経験は最初から生気的で自己組織化する物質的な場を開示しているという点で、本質的にアニミズム的であると彼は示唆して いる。デイヴィッド・エイブラムは、現代の認知科学と自然科学、そして多様な先住民の口承文化の視点的世界観を用い、物質が生きているという、豊かな多元 論と物語に基づく宇宙論を提唱した。彼は、このような関係的存在論は、感覚に注意を向け、感覚的な地形の優位性に注意を向けることによって、人類の自発的 な知覚体験と密接に一致し、人類を物質的に支えている動物、植物、土壌、山、水、天候パターンといった人間以上の共同体に対して、より敬意を払い、倫理的 な関係を築くことを推奨している[47][48]。 西洋の社会科学における長年の傾向とは対照的に、エイブラムはアニミズム的な経験を合理的に説明するのが一般的であり、理性それ自体についてアニミズム的 な説明を展開している。彼は、文明化された理性は、人間と彼ら自身の書かれた記号との間の強烈にアニミスティックな参加によってのみ維持されると主張す る。たとえば、ページやスクリーンに書かれた文字を読むと、すぐに「何が書いてあるかわかる」。読書は、アニミズムの強烈に集中した形態として理解するの が有益である。 このように理性についてアニミズム的な説明をすることは、アニミズムがより広範で包括的な用語であり、口承的で模倣的な経験様式が今もなお、私たちの文学 的で技術的な内省様式の根底にあり、それを支えていることを意味する。反省がこのような身体的で参加的な経験様式に根ざしていることがまったく認識されな かったり無意識であったりすると、反省的理性は機能不全に陥り、それを支えている身体的で感覚的な世界を意図せずに破壊してしまう[49]。 「我-汝(われ--なんじ)」の概念との関係 宗教学の研究者であるグラハム・ハーヴェイはアニミズムを「世界は人で満ちているが、そのうちの何人かは人間であり、人生は常に他者との関係の中で生きて いる」という信念であると定義した[19]。 彼の『現代アニミズムのハンドブック』(2013年)の中で、ハーヴェイはアニミズムの視点をマルティン・ブーバーの「私-it」とは対照的な「私- thou」に沿って特定している。ハーヴェイによれば、アニミストは世界と関係するために「我-汝」のアプローチをとり、それによって物や動物は「それ」 ではなく「汝」として扱われる[50]。 |

| Religion A tableau presenting figures of various cultures filling in mediator-like roles, often being termed as "shaman" in the literature There is ongoing disagreement (and no general consensus) as to whether animism is merely a singular, broadly encompassing religious belief[51] or a worldview in and of itself, comprising many diverse mythologies found worldwide in many diverse cultures.[52][53] This also raises a controversy regarding the ethical claims animism may or may not make: whether animism ignores questions of ethics altogether;[54] or, by endowing various non-human elements of nature with spirituality or personhood,[55] it in fact promotes a complex ecological ethics.[56] Concepts Distinction from pantheism Animism is not the same as pantheism, although the two are sometimes confused. Moreover, some religions are both pantheistic and animistic. One of the main differences is that while animists believe everything to be spiritual in nature, they do not necessarily see the spiritual nature of everything in existence as being united (monism) the way pantheists do. As a result, animism puts more emphasis on the uniqueness of each individual soul. In pantheism, everything shares the same spiritual essence, rather than having distinct spirits or souls.[57][58] For example, Giordano Bruno equated the world soul with God and espoused a pantheistic animism.[59][60] Fetishism / totemism Main articles: Fetishism and Totemism In many animistic world views, the human being is often regarded as on a roughly equal footing with other animals, plants, and natural forces.[61] African indigenous religions Traditional African religions: most religious traditions of Sub-Saharan Africa are basically a complex form of animism with polytheistic and shamanistic elements and ancestor worship.[62] In East Africa the Kerma culture display Animistic elements similar to other Traditional African religions. In contrast, the later polytheistic Napatan and Meroitic periods, with displays of animals in Amulets and the esteemed antiques of Lions, appear to be an Animistic culture rather than a polytheistic culture. The Kermans likely treated Jebel Barkal as a special sacred site, and passed it on to the Kushites and Egyptians who venerated the mesa.[63] In North Africa, the traditional Berber religion includes the traditional polytheistic, animist, and in some rare cases, shamanistic, religions of the Berber people.[citation needed] Asian origin religions Sculpture of the Buddha meditating under the Maha Bodhi Tree of Bodh Gaya in India Indian-origin religions In the Indian-origin religions, namely Hinduism, Buddhism, Jainism, and Sikhism, the animistic aspects of nature worship and ecological conservation are part of the core belief system. Matsya Purana, a Hindu text, has a Sanskrit language shloka (hymn), which explains the importance of reverence of ecology. It states: "A pond equals ten wells, a reservoir equals ten ponds, while a son equals ten reservoirs, and a tree equals ten sons."[64] Indian religions worship trees such as the Bodhi Tree and numerous superlative banyan trees, conserve the sacred groves of India, revere the rivers as sacred, and worship the mountains and their ecology. Panchavati are the sacred trees in Indic religions, which are sacred groves containing five type of trees, usually chosen from among the Vata (Ficus benghalensis, Banyan), Ashvattha (Ficus religiosa, Peepal), Bilva (Aegle marmelos, Bengal Quince), Amalaki (Phyllanthus emblica, Indian Gooseberry, Amla), Ashoka (Saraca asoca, Ashok), Udumbara (Ficus racemosa, Cluster Fig, Gular), Nimba (Azadirachta indica, Neem) and Shami (Prosopis spicigera, Indian Mesquite).[65][66] Thimmamma Marrimanu – the Great Banyan tree revered by the people of Indian-origin religions such as Hinduism (including Vedic, Shaivism, Dravidian Hinduism), Buddhism, Jainism, and Sikhism During Vat Purnima festival, married women tie threads around a banyan tree in India. The banyan is considered holy in several religious traditions of India. The Ficus benghalensis is the national tree of India.[67] Vat Purnima is a Hindu festival related to the banyan tree, and is observed by married women in North India and in the Western Indian states of Maharashtra, Goa, Gujarat.[68] For three days of the month of Jyeshtha in the Hindu calendar (which falls in May–June in the Gregorian calendar) married women observe a fast, tie threads around a banyan tree, and pray for the well-being of their husbands.[69] Thimmamma Marrimanu, sacred to Indian religions, has branches spread over five acres and was listed as the world's largest banyan tree in the Guinness World Records in 1989.[70][71] In Hinduism, the leaf of the banyan tree is said to be the resting place for the god Krishna. In the Bhagavat Gita, Krishna said, "There is a banyan tree which has its roots upward and its branches down, and the Vedic hymns are its leaves. One who knows this tree is the knower of the Vedas." (Bg 15.1) In Buddhism's Pali canon, the banyan (Pali: nigrodha)[72] is referenced numerous times.[73] Typical metaphors allude to the banyan's epiphytic nature, likening the banyan's supplanting of a host tree as comparable to the way sensual desire (kāma) overcomes humans.[74] Mun (also known as Munism or Bongthingism) is the traditional polytheistic, animist, shamanistic, and syncretic religion of the Lepcha people.[75][76][77] Sanamahism is an ethnic religion of the Meitei people of Kangleipak (Meitei for 'Manipur') in Northeast India. It is a polytheistic and animist religion and is named after Lainingthou Sanamahi, one of the most important deities of the Meitei faith.[78][79][80] Chinese religions Shendao (Chinese: 神道; pinyin: shéndào; lit. 'the Way of the Gods') is a term originated by Chinese folk religions influenced by, Mohist, Confucian and Taoist philosophy, referring to the divine order of nature or the Wuxing. The Shang dynasty's state religion was practiced from 1600 BCE to 1046 BCE, and was built on the idea of spiritualizing natural phenomena. Japan and Shinto [icon] This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (July 2021) Shinto is the traditional Japanese folk religion and has many animist aspects. The kami (神), a class of supernatural beings, are central to Shinto. All things, including natural forces and well-known geographical locations, are thought to be home to the kami. The kami are worshipped at kamidana household shrines, family shrines, and jinja public shrines. The Ryukyuan religion of the Ryukyu islands is distinct from Shinto, but shares similar characteristics. Kalash people [icon] This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (July 2021) Kalash people of Northern Pakistan follow an ancient animistic religion identified with an ancient form of Hinduism.[81] Korea [icon] This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (July 2021) Muism, the native Korean belief, has many animist aspects.[82] The various deities, called kwisin, are capable of interacting with humans and causing problems if they are not honoured appropriately. A 1922 photograph of an Itneg priestess in the Philippines making an offering to an apdel, a guardian anito spirit of her village that reside in the water-worn stones known as pinaing[83] Philippines indigenous religions In the indigenous Philippine folk religions, pre-colonial religions of Philippines and Philippine mythology, animism is part of their core beliefs as demonstrated by the belief in Anito and Bathala as well as their conservation and veneration of sacred Indigenous Philippine shrines, forests, mountains and sacred grounds. Anito (lit. '[ancestor] spirit') refers to the various indigenous shamanistic folk religions of the Philippines, led by female or feminized male shamans known as babaylan. It includes belief in a spirit world existing alongside and interacting with the material world, as well as the belief that everything has a spirit, from rocks and trees to animals and humans to natural phenomena.[84][85] In indigenous Filipino belief, the Bathala is the omnipotent deity which was derived from Sanskrit word for the Hindu supreme deity bhattara,[86][87] as one of the ten avatars of the Hindu god Vishnu.[88][89] The omnipotent Bathala also presides over the spirits of ancestors called Anito.[90][91][92][93] Anitos serve as intermediaries between mortals and the divine, such as Agni (Hindu) who holds the access to divine realms; for this reason they are invoked first and are the first to receive offerings, regardless of the deity the worshipper wants to pray to.[94][95] Abrahamic religions Animism also has influences in Abrahamic religions. The Old Testament and the Wisdom literature preach the omnipresence of God (Jeremiah 23:24; Proverbs 15:3; 1 Kings 8:27), and God is bodily present in the incarnation of his Son, Jesus Christ. (Gospel of John 1:14, Colossians 2:9).[96] Animism is not peripheral to Christian identity but is its nurturing home ground, its axis mundi. In addition to the conceptual work the term animism performs, it provides insight into the relational character and common personhood of material existence.[3] With rising awareness of ecological preservation, recently theologians like Mark I. Wallace argue for animistic Christianity with a biocentric approach that understands God being present in all earthly objects, such as animals, trees, and rocks.[97] Pre-Islamic Arab religion [icon] This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (July 2021) Pre-Islamic Arab religion can refer to the traditional polytheistic, animist, and in some rare cases, shamanistic, religions of the peoples of the Arabian Peninsula. The belief in jinn, invisible entities akin to spirits in the Western sense dominant in the Arab religious systems, hardly fit the description of Animism in a strict sense. The jinn are considered to be analogous to the human soul by living lives like that of humans, but they are not exactly like human souls neither are they spirits of the dead.[98]: 49 It is unclear if belief in jinn derived from nomadic or sedentary populations.[98]: 51 New religious movements Some modern pagan groups, including Eco-pagans, describe themselves as animists, meaning that they respect the diverse community of living beings and spirits with whom humans share the world and cosmos.[99] The New Age movement commonly demonstrates animistic traits in asserting the existence of nature spirits.[100] Shamanism Main article: Shamanism A shaman is a person regarded as having access to, and influence in, the world of benevolent and malevolent spirits, who typically enters into a trance state during a ritual, and practices divination and healing.[101] According to Mircea Eliade, shamanism encompasses the premise that shamans are intermediaries or messengers between the human world and the spirit worlds. Shamans are said to treat ailments and illnesses by mending the soul. Alleviating traumas affecting the soul or spirit restores the physical body of the individual to balance and wholeness. The shaman also enters supernatural realms or dimensions to obtain solutions to problems afflicting the community. Shamans may visit other worlds or dimensions to bring guidance to misguided souls and to ameliorate illnesses of the human soul caused by foreign elements. The shaman operates primarily within the spiritual world, which in turn affects the human world. The restoration of balance results in the elimination of the ailment.[102] Abram, however, articulates a less supernatural and much more ecological understanding of the shaman's role than that propounded by Eliade. Drawing upon his own field research in Indonesia, Nepal, and the Americas, Abram suggests that in animistic cultures, the shaman functions primarily as an intermediary between the human community and the more-than-human community of active agencies—the local animals, plants, and landforms (mountains, rivers, forests, winds, and weather patterns, all of which are felt to have their own specific sentience). Hence, the shaman's ability to heal individual instances of dis-ease (or imbalance) within the human community is a byproduct of their more continual practice of balancing the reciprocity between the human community and the wider collective of animate beings in which that community is embedded.[103] |

宗教 様々な文化の人物が仲介者のような役割を果たし、文献ではしばしば「シャーマン」と呼ばれる。 アニミズムが単に単一の、広範に包含される宗教的信念[51]なのか、それとも多くの多様な文化において世界中で見られる多くの多様な神話からなるそれ自 体の世界観なのかについては、現在も意見が分かれている(そして一般的なコンセンサスは得られていない)[52][53]。 [52][53]このことはまた、アニミズムが倫理的な主張をするのかしないのか、つまりアニミズムが倫理の問題を完全に無視しているのか[54]、ある いは自然の様々な非人間的要素に霊性や人格性を与えることによって[55]、実際には複雑な生態倫理を促進しているのか[56]、といった論争を引き起こ している。 概念 汎神論との区別 アニミズムは汎神論とは異なるが、両者は混同されることがある。さらに、汎神論的であると同時にアニミズム的である宗教もある。主な違いの1つは、アニミ ストはすべてのものが霊的な性質を持っていると信じているが、汎神論者のように、存在するすべてのものの霊的な性質が必ずしも1つ(一元論)であるとは考 えていないということである。その結果、アニミズムは個々の魂の独自性をより重視する。例えば、ジョルダーノ・ブルーノは世界の魂を神と同一視し、汎神論 的なアニミズムを信奉していた[59][60]。 フェティシズム/トーテミズム 主な記事 フェティシズムとトーテミズム 多くのアニミズム的世界観において、人間はしばしば他の動物、植物、自然の力とほぼ同等の立場にあると見なされている[61]。 アフリカの土着宗教 アフリカの伝統宗教:サハラ以南のアフリカのほとんどの宗教的伝統は、基本的に多神教的でシャーマニズム的な要素と祖先崇拝を持つ複雑なアニミズムの形態 である[62]。 東アフリカではカーマ文化が他の伝統的アフリカ宗教と同様のアニミズム的要素を示している。対照的に、後の多神教的なナパタン時代とメロイト時代は、ア ミュレットに動物を展示したり、ライオンの骨董品を珍重したりすることから、多神教文化というよりはむしろアニミズム文化であるように見える。ケルマン人 はおそらくジェベル・バルカルを特別な聖地として扱い、それをメサを崇拝するクシ人やエジプト人に伝えたのであろう[63]。 北アフリカでは、伝統的なベルベル人の宗教には、ベルベル人の伝統的な多神教、アニミズム、まれにシャーマニズム的な宗教が含まれる[要出典]。 アジア起源の宗教 インドのブッダガヤの大菩提樹の下で瞑想する仏陀の彫刻 インド起源の宗教 インド起源の宗教、すなわちヒンドゥー教、仏教、ジャイナ教、シーク教では、自然崇拝と生態系保全のアニミズム的側面が中核的な信仰体系の一部となってい る。 ヒンドゥー教のテキストであるマツヤ・プラーナには、サンスクリット語のシュローカ(讃歌)があり、エコロジーへの畏敬の念の重要性を説いている。そこに はこう書かれている: 「池は10の井戸に等しく、貯水池は10の池に等しく、息子は10の貯水池に等しく、木は10の息子に等しい」[64]。インドの宗教は、菩提樹や数多く の最上級のガジュマルなどの木を崇拝し、インドの神聖な木立を保護し、川を神聖なものとして崇め、山とその生態系を崇拝する。 パンチャヴァティとは、インドの宗教における聖なる木々のことで、通常はヴァータ(Ficus benghalensis、ガジュマル)、アシュヴァッタ(Ficus religiosa、ピーパル)、ビルヴァ(Aegle marmelos、ベンガルカリン)、アムバ(Aegle marmelos、ベンガルカリン)の中から選ばれた5種類の木々を含む聖なる木立のことである、 ベンガルカリン)、アマラキ(Phyllanthus emblica、インドグーズベリー、アムラ)、アショカ(Saraca asoca、アショク)、ウドゥンバラ(Ficus racemosa、クラスターいちじく、グラー)、ニンバ(Azadirachta indica、ニーム)、シャミ(Prosopis spicigera、インドメスキート)。 [65][66] ヒンドゥー教(ヴェーダ、シャイヴィズム、ドラヴィダ・ヒンドゥー教を含む)、仏教、ジャイナ教、シーク教など、インドに起源を持つ宗教の人々が崇める大 榕樹。 ヴァット・プルニマ祭では、結婚した女性がガジュマルの木に糸を結ぶ。 ガジュマルはインドのいくつかの宗教的伝統において神聖視されている。ガジュマルはインドの国樹である[67]。ヴァット・プルニマはガジュマルの木に関 連するヒンドゥー教の祭りで、北インドと西インドのマハラシュトラ州、ゴア州、グジャラート州で既婚女性によって守られている[68]。 [68]ヒンドゥー暦のジェイシュタ月(グレゴリオ暦の5月~6月にあたる)の3日間、既婚女性は断食を行い、ガジュマルの木に糸を結び、夫の幸福を祈る [69]。 インドの宗教にとって神聖なティンマンマリマヌは、5エーカーに及ぶ枝を持ち、1989年に世界最大のガジュマルの木としてギネス・ワールド・レコーズに 登録された[70][71]。 ヒンドゥー教では、ガジュマルの葉はクリシュナ神の安息の場所と言われている。バガヴァット・ギーターの中で、クリシュナは「根を上に、枝を下に持つガ ジュマルの木があり、ヴェーダの賛美歌はその葉である。この木を知る者は、ヴェーダを知る者である。" (Bg 15.1) 仏教のパーリ語正典では、ガジュマル(パーリ語: nigrodha)[72]は何度も言及されている[73]。典型的な比喩はガジュマルの着生的な性質を暗示し、ガジュマルが宿主の木に取って代わること を、官能的な欲望(kāma)が人間に打ち勝つ方法に例える[74]。 ムンはレプチャ族の伝統的な多神教、アニミズム、シャーマニズム、シンクレティックの宗教である[75][76][77]。 サナマー教(Sanamahism)は、北東インドのカンゲリパック(Meiteiは「マニプール」の意)のメイテイ族の民族宗教である。多神教でアニミ ズムの宗教であり、メイテイ信仰の最も重要な神々の一人であるライニングトー・サナマヒにちなんで名付けられた[78][79][80]。 中国の宗教 神道(中国語: 神道、ピンイン: shéndào。 紀元前1600年から紀元前1046年まで行われていた殷王朝の国教で、自然現象を霊化するという考えに基づいていた。 日本と神道 [アイコン] このセクションは拡張が必要です。追加することで貢献できます。(2021年7月) 神道は日本の伝統的な民間宗教であり、多くのアニミズム的側面を持っている。超自然的な存在の一種である神(カミ)は、神道の中心的存在である。自然の力 やよく知られた地理的な場所など、あらゆるものがカミの住処であると考えられている。カミは神棚、家族神社、神社に祀られている。 琉球諸島の宗教は神道とは異なるが、似たような特徴を持つ。 カラシュ族 [アイコン] このセクションは拡張が必要です。追加することで貢献できます。(2021年7月) パキスタン北部のカラシュ人は、ヒンドゥー教の古代形態と同一視される古代のアニミズム宗教を信仰している[81]。 韓国 [アイコン]。 このセクションは拡張が必要です。追加してください。(2021年7月) 韓国固有の信仰である無神論は、アニミズム的な側面を多く持っている[82]。 クウィシンと呼ばれる様々な神々は人間と交流する能力があり、適切に敬わなければ問題を引き起こす。 1922年、フィリピンのイトネグの巫女が、ピナインとして知られる水に濡れた石に宿る村の守護アニトの精霊、アプデルに供物を捧げている写真[83]。 フィリピン土着の宗教 フィリピン先住民の民間宗教、フィリピンの先植民地宗教、フィリピン神話では、アニトとバタラへの信仰や、フィリピン先住民の神聖な神社、森林、山、聖地 の保護と崇拝によって示されるように、アニミズムは彼らの中心的な信仰の一部である。 アニト(「祖先の霊」)とは、ババイランと呼ばれる女性または女性化した男性のシャーマンが率いる、フィリピンのさまざまな先住民のシャーマニズム的民間 宗教を指す。この宗教には、物質世界とともに存在し、物質世界と相互作用する精神世界に対する信仰や、岩や木、動物、人間、自然現象に至るまで、あらゆる ものに精神が宿るという信仰が含まれる[84][85]。 フィリピン土着の信仰では、バタラは全能の神であり、ヒンドゥー教の最高神バッタラを意味するサンスクリット語に由来する[86][87]。 [90][91][92][93]アニトは、アグニ(ヒンドゥー教)のように神の領域へのアクセスを保持する、人間と神との間の仲介者としての役割を果た す。このため、アニトは崇拝者が祈りたい神にかかわらず、最初に呼び出され、最初に供物を受け取る。 アブラハムの宗教 アニミズムはアブラハムの宗教にも影響を及ぼしている。 旧約聖書と知恵文学は神の遍在を説いており(エレミヤ23:24、箴言15:3、列王記上8:27)、神は御子イエス・キリストの受肉において肉体的に存 在している。(アニミズムは、キリスト教のアイデンティティにとって周辺的なものではなく、キリスト教を育む拠り所であり、その軸である。アニミズムとい う用語が果たす概念的な働きに加えて、物質的存在の関係的な性格と共通の人格性についての洞察も提供している[3]。 生態系保全に対する意識の高まりとともに、最近ではマーク・I・ウォレスのような神学者たちが、動物、木、岩などの地上のあらゆるものの中に神が存在する と理解する生物中心主義的なアプローチでアニミズム的キリスト教を主張している[97]。 イスラーム以前のアラブの宗教 [アイコン]。 このセクションは拡張が必要です。追加してください。(2021年7月) イスラーム以前のアラブの宗教とは、アラビア半島の民族の伝統的な多神教、アニミズム、まれにシャーマニズムの宗教を指すことがある。アラブの宗教体系で 支配的な、西洋的な意味での精霊に似た目に見えない存在であるジンへの信仰は、厳密な意味でのアニミズムという表現には当てはまりにくい。ジンは人間と同 じような生活を送ることで人間の魂に類似していると考えられているが、人間の魂とまったく同じでもなく、死者の霊でもない[98]: 49 ジンに対する信仰が遊牧民から派生したものなのか定住民から派生したものなのかは不明である[98]: 51 新しい宗教運動 エコ・ペイガンを含む現代の異教徒のグループの中には、自らをアニミストと表現するものがある。これは、人間が世界と宇宙を共有している多様な生きとし生 けるものの共同体や精霊を尊重するという意味である[99]。 ニューエイジ運動は一般的に自然霊の存在を主張するというアニミズム的特徴を示している[100]。 シャーマニズム 主な記事 シャーマニズム シャーマンとは、善意や悪意のある精霊の世界にアクセスし、影響力を持つとみなされる人物のことであり、通常儀式の際にトランス状態に入り、占いやヒーリ ングを実践する[101]。 ミルチェア・エリアーデによれば、シャーマニズムはシャーマンが人間界と霊界の間の仲介者またはメッセンジャーであるという前提を包含している。シャーマ ンは魂を修復することによって病気や疾患を治療すると言われている。魂やスピリットに影響を与えるトラウマを緩和することで、個人の肉体をバランスと完全 性に回復させる。シャーマンはまた、超自然的な領域や次元に入り込み、コミュニティを苦しめている問題の解決策を得る。シャーマンは他の世界や次元を訪 れ、誤った魂に導きをもたらしたり、異質な要素によって引き起こされる人間の魂の病気を改善したりすることもある。シャーマンは主に精神世界で活動し、そ れが人間世界に影響を与える。バランスを回復させることで、病気が取り除かれる[102]。 しかしアブラムは、エリアーデが提唱したものよりも、シャーマンの役割について、より超自然的ではなく、より生態学的な理解を明確にしている。エイブラム は、インドネシア、ネパール、アメリカ大陸における彼自身の現地調査をもとに、アニミズム文化においては、シャーマンは主に、人間社会と、その地域の動 物、植物、地形(山、川、森、風、天候パターンなど、それらすべてが固有の感覚を持っていると考えられている)といった、人間以上の存在である共同体との 仲介役として機能することを示唆している。それゆえ、シャーマンが人間の共同体内の個々の不調(または不均衡)を癒す能力は、人間の共同体と、その共同体 が組み込まれているより広範な生きとし生けるものの集合体との間の相互性のバランスをとるという、より継続的な実践の副産物なのである[103]。 |

| Animist life Non-human animals Animism entails the belief that all living things have a soul, and thus, a central concern of animist thought surrounds how animals can be eaten, or otherwise used for humans' subsistence needs.[104] The actions of non-human animals are viewed as "intentional, planned and purposive",[105] and they are understood to be persons, as they are both alive, and communicate with others.[106] In animist worldviews, non-human animals are understood to participate in kinship systems and ceremonies with humans, as well as having their own kinship systems and ceremonies.[107] Harvey cited an example of an animist understanding of animal behavior that occurred at a powwow held by the Conne River Mi'kmaq in 1996; an eagle flew over the proceedings, circling over the central drum group. The assembled participants called out kitpu ('eagle'), conveying welcome to the bird and expressing pleasure at its beauty, and they later articulated the view that the eagle's actions reflected its approval of the event, and the Mi'kmaq's return to traditional spiritual practices.[108] In animism, rituals are performed to maintain relationships between humans and spirits. Indigenous peoples often perform these rituals to appease the spirits and request their assistance during activities such as hunting and healing. In the Arctic region, certain rituals are common before the hunt as a means to show respect for the spirits of animals.[109] Flora Some animists also view plant and fungi life as persons and interact with them accordingly.[110] The most common encounter between humans and these plant and fungi persons is with the former's collection of the latter for food, and for animists, this interaction typically has to be carried out respectfully.[111] Harvey cited the example of Māori communities in New Zealand, who often offer karakia invocations to sweet potatoes as they dig up the latter. While doing so, there is an awareness of a kinship relationship between the Māori and the sweet potatoes, with both understood as having arrived in Aotearoa together in the same canoes.[111] In other instances, animists believe that interaction with plant and fungi persons can result in the communication of things unknown or even otherwise unknowable.[110] Among some modern Pagans, for instance, relationships are cultivated with specific trees, who are understood to bestow knowledge or physical gifts, such as flowers, sap, or wood that can be used as firewood or to fashion into a wand; in return, these Pagans give offerings to the tree itself, which can come in the form of libations of mead or ale, a drop of blood from a finger, or a strand of wool.[112] The elements Various animistic cultures also comprehend stones as persons.[113] Discussing ethnographic work conducted among the Ojibwe, Harvey noted that their society generally conceived of stones as being inanimate, but with two notable exceptions: the stones of the Bell Rocks and those stones which are situated beneath trees struck by lightning, which were understood to have become Thunderers themselves.[114] The Ojibwe conceived of weather as being capable of having personhood, with storms being conceived of as persons known as 'Thunderers' whose sounds conveyed communications and who engaged in seasonal conflict over the lakes and forests, throwing lightning at lake monsters.[114] Wind, similarly, can be conceived as a person in animistic thought.[115] The importance of place is also a recurring element of animism, with some places being understood to be persons in their own right.[116] Spirits Animism can also entail relationships being established with non-corporeal spirit entities.[117] |

アニミストの生活 人間以外の動物 アニミズムはすべての生きとし生けるものには魂があるという信念を伴うため、アニミズム思想の中心的な関心事は、動物がどのように食べられるか、あるいは 人間の生計の必要性のためにどのように利用されるかをめぐっている[104]。人間以外の動物の行動は「意図的、計画的、目的的」[105]と見なされ、 生きており、他者とコミュニケーションをとることから、彼らは人間であると理解されている[106]。 アニミズムの世界観では、人間以外の動物は人間との親族制度や儀式に参加し、独自の親族制度や儀式を持つと理解されている[107]。ハーヴェイは 1996年にコン・リバー・ミクマクが開催したパウワウで起こった動物の行動に対するアニミズム的理解の例を挙げている。集まった参加者はkitpu (「鷲」)と呼び、鳥への歓迎を伝え、その美しさへの喜びを表現した。彼らは後に、鷲の行動はこの行事を承認し、ミックマックが伝統的な精神的慣習に回帰 したことを反映しているという見解を明らかにした[108]。 アニミズムでは、人間と精霊の関係を維持するために儀式が行われる。先住民は狩猟やヒーリングなどの活動の際に、精霊を鎮め、その援助を求めるためにこれ らの儀式を行うことが多い。北極地方では、動物の精霊に敬意を示す手段として、狩りの前に特定の儀式を行うことが一般的である[109]。 植物 一部のアニミストは植物や菌類の生命を人とみなしており、それに応じて彼らと交流している[110]。人間とこれらの植物や菌類の生命との最も一般的な出 会いは、前者が食用として後者を採取することであり、アニミストにとってこの交流は一般的に敬意をもって行われなければならない[111]。ハーヴェイは ニュージーランドのマオリ族のコミュニティの例を挙げており、彼らはサツマイモを掘り起こす際にしばしばカラキアの呼びかけをサツマイモに捧げている。そ うすることで、マオリとサツマイモの間に親族関係があることが意識され、両者は同じカヌーで一緒にアオテアロアにたどり着いたと理解される[111]。 他の例では、アニミストは植物や菌類の人物との相互作用によって、未知のもの、あるいはそうでなければ知ることのできないものとのコミュニケーションがも たらされると信じている[110]。 [その見返りとして、これらの異教徒は木そのものに供物を捧げる。供物は、蜂蜜酒やエールの酒、指の血の一滴、羊毛の一筋といった形で与えられる [112]。 元素 様々なアニミズム的文化もまた、石を人として理解している[113]。オジブエの間で行われた民族誌的研究についてハーヴェイは、彼らの社会は一般的に石 を無生物として考えているが、2つの顕著な例外があると述べている。 [114]オジブエは天候を人格を持つことが可能であると考え、嵐は「サンダー」として知られる人物として考えられ、その音は通信を伝え、湖や森をめぐっ て季節ごとに争いを繰り広げ、湖の怪物に稲妻を投げつけた[114]。 場所の重要性もまたアニミズムの繰り返し見られる要素であり、いくつかの場所はそれ自体が人であると理解されている[116]。 精霊 アニミズムはまた、肉体を持たない精霊との関係を構築することを伴うことがある[117]。 |

| Other usage Science In the early 20th century, William McDougall defended a form of animism in his book Body and Mind: A History and Defence of Animism (1911). Physicist Nick Herbert has argued for "quantum animism" in which the mind permeates the world at every level: The quantum consciousness assumption, which amounts to a kind of "quantum animism" likewise asserts that consciousness is an integral part of the physical world, not an emergent property of special biological or computational systems. Since everything in the world is on some level a quantum system, this assumption requires that everything be conscious on that level. If the world is truly quantum animated, then there is an immense amount of invisible inner experience going on all around us that is presently inaccessible to humans, because our own inner lives are imprisoned inside a small quantum system, isolated deep in the meat of an animal brain.[118] Werner Krieglstein wrote regarding his quantum Animism: Herbert's quantum Animism differs from traditional Animism in that it avoids assuming a dualistic model of mind and matter. Traditional dualism assumes that some kind of spirit inhabits a body and makes it move, a ghost in the machine. Herbert's quantum Animism presents the idea that every natural system has an inner life, a conscious center, from which it directs and observes its action.[119] In Error and Loss: A Licence to Enchantment,[120] Ashley Curtis (2018) has argued that the Cartesian idea of an experiencing subject facing off with an inert physical world is incoherent at its very foundation and that this incoherence is consistent with rather than belied by Darwinism. Human reason (and its rigorous extension in the natural sciences) fits an evolutionary niche just as echolocation does for bats and infrared vision does for pit vipers, and is epistemologically on a par with, rather than superior to, such capabilities. The meaning or aliveness of the "objects" we encounter, rocks, trees, rivers, and other animals, thus depends for its validity not on a detached cognitive judgment, but purely on the quality of our experience. The animist experience, or the wolf's or raven's experience, thus become licensed as equally valid worldviews to the modern western scientific one; they are indeed more valid, since they are not plagued with the incoherence that inevitably arises when "objective existence" is separated from "subjective experience." Socio-political impact Harvey opined that animism's views on personhood represented a radical challenge to the dominant perspectives of modernity, because it accords "intelligence, rationality, consciousness, volition, agency, intentionality, language, and desire" to non-humans.[121] Similarly, it challenges the view of human uniqueness that is prevalent in both Abrahamic religions and Western rationalism.[122] Art and literature Animist beliefs can also be expressed through artwork.[123] For instance, among the Māori communities of New Zealand, there is an acknowledgement that creating art through carving wood or stone entails violence against the wood or stone person and that the persons who are damaged therefore have to be placated and respected during the process; any excess or waste from the creation of the artwork is returned to the land, while the artwork itself is treated with particular respect.[124] Harvey, therefore, argued that the creation of art among the Māori was not about creating an inanimate object for display, but rather a transformation of different persons within a relationship.[125] Harvey expressed the view that animist worldviews were present in various works of literature, citing such examples as the writings of Alan Garner, Leslie Silko, Barbara Kingsolver, Alice Walker, Daniel Quinn, Linda Hogan, David Abram, Patricia Grace, Chinua Achebe, Ursula Le Guin, Louise Erdrich, and Marge Piercy.[126] Animist worldviews have also been identified in the animated films of Hayao Miyazaki.[127][128][129][130] |

その他 科学 20世紀初頭、ウィリアム・マクドゥーガルは著書『身体と心』(Body and Mind)の中でアニミズムの一形態を擁護した: A History and Defence of Animism」(1911年)という著書で、アニミズムの一形態を擁護している。 物理学者のニック・ハーバートは、心があらゆるレベルで世界に浸透しているという「量子アニミズム」を主張している: 量子意識の仮定は、一種の "量子アニミズム "に相当するが、同様に、意識は物理世界の不可欠な一部であり、特殊な生物学的システムや計算システムの創発的特性ではないと主張する。世界のすべてがあ るレベルでは量子システムであるため、この仮定は、そのレベルではすべてが意識的であることを必要とする。もし世界が本当に量子アニメーションの世界であ るならば、私たちの周りでは、現在人間にはアクセスできない膨大な量の目に見えない内的体験が行われていることになる。 ヴェルナー・クリーグルシュタインは、彼の量子アニミズムについてこう書いている: ハーバートの量子アニミズムが伝統的なアニミズムと異なるのは、心と物質の二元論的モデルを仮定しない点である。伝統的な二元論は、ある種の精神が肉体に 宿り、機械の中の幽霊のように肉体を動かすと仮定する。ハーバートの量子アニミズムは、あらゆる自然システムには内なる生命、意識的な中心があり、そこか らその行動を指示し、観察しているという考えを提示している[119]。 Error and Loss: A Licence to Enchantment』の中で、[120] Ashley Curtis(2018年)は、経験する主体が不活性な物理的世界と対峙するというデカルト的な考えはその根底において支離滅裂であり、この支離滅裂さは ダーウィニズムによって否定されるのではなく、むしろ一貫していると主張している。人間の理性(および自然科学におけるその厳密な拡張)は、コウモリに とってのエコロケーションやマムシにとっての赤外線視力と同じように、進化上のニッチに適合しており、認識論的にはそうした能力に優るどころか、同等であ る。岩、木、川、その他の動物など、私たちが遭遇する "物体 "の意味や生命性は、このように、その妥当性において、切り離された認知的判断ではなく、純粋に私たちの経験の質に依存している。アニミズムの経験、ある いはオオカミやワタリガラスの経験は、こうして現代西洋の科学的世界観と同等に有効な世界観として認められるようになる。 社会政治的影響 ハーヴェイは、アニミズムの人格観は近代の支配的な視点に対する根本的な挑戦であり、それは「知性、合理性、意識、意志、主体性、意図性、言語、欲望」を 非人間に認めているからである[121]と論評した。同様に、それはアブラハムの宗教と西洋の合理主義の両方に広まっている人間の独自性についての見解に 挑戦している[122]。 芸術と文学 例えば、ニュージーランドのマオリ族のコミュニティでは、木や石を彫って芸術作品を創作することは、木や石の人に対する暴力を伴うという認識があり、従っ て、その過程で損害を受けた人はなだめられ、尊重されなければならない。 [それゆえハーヴェイは、マオリにおける芸術の創造とは、展示するための無生物を創造することではなく、むしろ関係性のなかでさまざまな人物を変容させる ことであると主張した[125]。 ハーヴェイはアニミズム的世界観が様々な文学作品に存在するという見解を表明し、その例としてアラン・ガーナー、レスリー・シルコ、バーバラ・キングソル バー、アリス・ウォーカー、ダニエル・クイン、リンダ・ホーガン、デイヴィッド・エイブラム、パトリシア・グレイス、チヌア・アチェベ、アーシュラ・ル・ グウィン、ルイーズ・エルドリッチ、マージ・ピアシーの著作などを挙げている[126]。 アニミズムの世界観は宮崎駿のアニメーション映画にも確認されている[127][128][129][130]。 |

| Anecdotal cognitivism Animatism Anima mundi Dayawism Ecotheology Hylozoism Mana Mauri (life force) Kaitiaki Panpsychism Religion and environmentalism Sacred trees Shamanism Wildlife totemization |

逸話的認知主義 アニマティズム アニマ・ムンディ ダヤウィズム 生態神学 ハイロゾイズム マナ マウリ(生命力) カイティアキ 汎心論 宗教と環境主義 聖なる木 シャーマニズム 野生動物のトーテム化 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Animism |

|

《旧

版の説明です》

アニミズム(animism)とは,19世紀の文化進化主義者タイラー (E.B.Tylor)の用語です。

また、 アニミズムは、アニマティズム(animatism)と言われることもあります。したがって、もっとも原始的な宗教の萌芽的状態における、霊的存在への信 仰をアニミズム——ラテン語の霊魂 (anima)に由来——と命名しました。 彼は(長年の研究の結果)、宗教は自然崇拝から死者崇拝や呪物崇拝(フェティシズム)を経て 多神教になり、そして最後に一神教へ進化したのではないかと考 えました。ただし、タイラーによると、アニミズムの形態は高度の信仰の段階になってもすぐに消失するのではなく、形を変 えて生き残るといっています。 今日、原始的な思考としてのみアニミズムを理解する人類学者はほとんどいません。にもかかわらず、初期の人類 学者たちが、宗教のはじまりをいったい、どのように取り扱おうとしたのか、また未開から文明への宗教の「進化」というものをどのような観点からみようとし たのかについて教えてくれる点で、この議論は今なお(今だからこそ)考察するに値するテーマなのです。

現在は、日常世界のさまざまな諸物に霊魂が宿っており、それを敬う信仰の形態を指して、緩やかな意味あいにお いてアニミズムと呼んでいます。

Animals are "good

to think with" and are just a

example of human need to classify....

10日

間暗闇に放っておいた電波時計(左)が、蛍光灯の照射数時間で「生き返った」——この表現は電波を使った人にしかわからないでしょう?(^。^):

右はマレーシア産、中国アセンブリーのセイコー・ファイブ(自動巻)です。カシオの電波はマルチレシーバでないのと、ボタン操作がめんどいので、海外では

使いません。

こ の時代の背景を知るには「プ レ人類学 (pre-anthropology)」を参照にしてください。

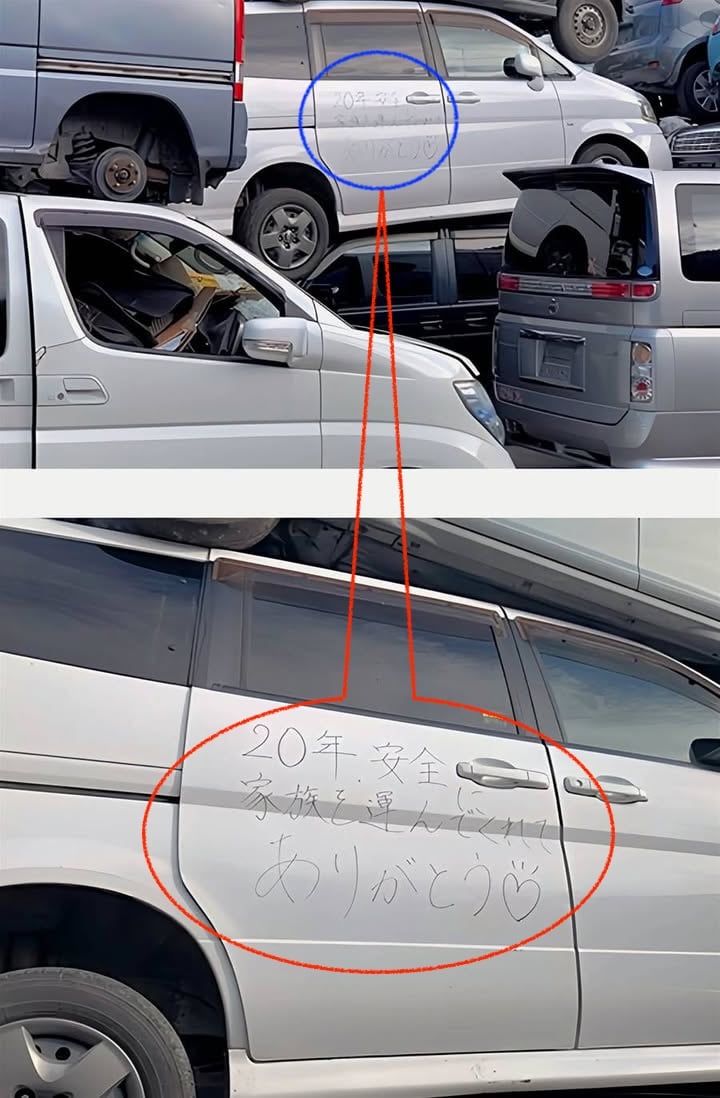

★自動車の廃車置き場におかれた旧オーナー家族によるメッセージ「20年安全に運んでくれてありがとう���」

リンク

文献

その他の情報

鎮忘斎教授の猿にもわかる文化人類学プロジェクト協 賛

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

++

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆