Biopower, Bio-politic, Political Economy of

Health,

and Body-politic, せい・けんりょく

生権力

Biopower, Bio-politic, Political Economy of

Health,

and Body-politic, せい・けんりょく

生権力=バイオパワーとは、他 者の身体に介在する権力(性)のことをさす。生権力は、この項目のように生・権力(せいけんりょく)と書かれたり、英語の外来語ふうに「バ イオパワー(biopower)」——洗 剤の効能のようだが——と呼ばれたり、フランス語風にカッコよく「ビオプヴァー(le biopouvoir)」と呼ぶ人 がいる。呼称はたくさんあるが、指し示す内容を統一しないと、混乱の原因になるので、この項目は、ミッシェル・フーコーの議論に沿いながら解説する(→「バイオポリティクス」「同研 究ノート」)。

ミッシェル・フーコーによると、(1)身体の従属主体

の構築=アナトモポリティークと、(2)個体数(人口)の制御=ビオポリティーク、という2つの側面からなる多種多様な技法の開花=爆発によって生まれ

る。( “[A]n explosion of numerous and diverse techniques for achieving

the subjugations of bodies and the control of populations” (Foucault,

History of Sexuality, Vol.I, p.140).)

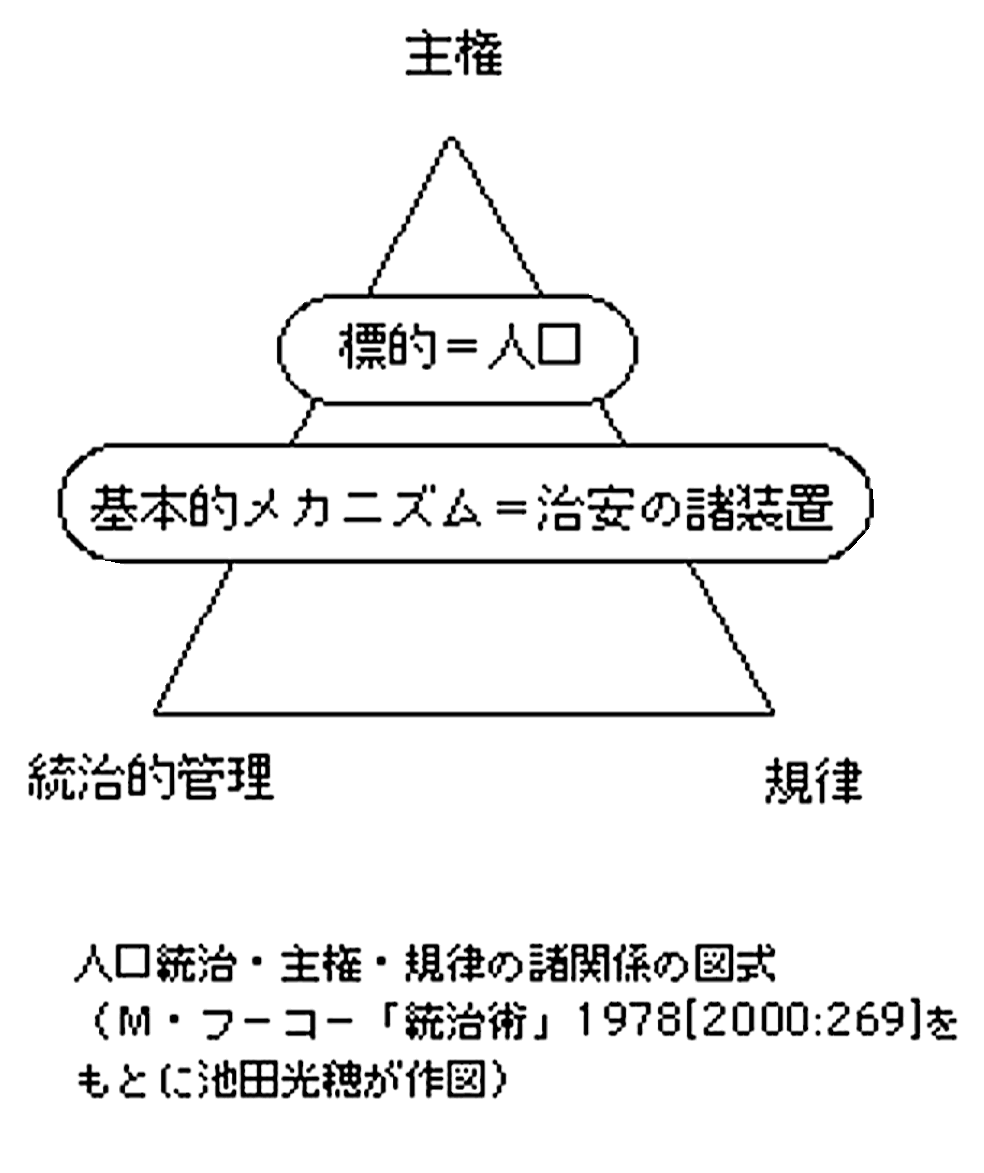

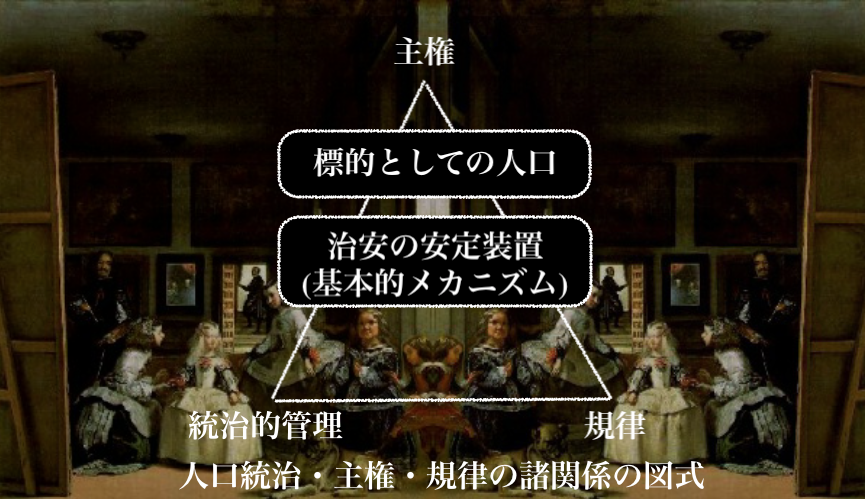

医療における権力論の研究は、M・フーコーの、生−権力や統治性の議論が登場して根本的な変化を 遂げた。

それまで、医療が考えてきた権力は、患者をコントロールするむき出しの力、患者をモルモットにす る服従を強制する権力というのが定番であった。今でも、このような権力論の図式にのっかって、「医者は権力を行使するからリベラルでなければならない」 「医 師の権力は神聖」(→医療聖職論)ということを主張する主に高齢者を中心としたオールド・リベラストの方々がいる。

ところが、権力の作用の多様なあり方や、統治性 (governmentality)にかんするフーコーの議論に触れたものは、権力 というものは、我々が考えるほど(1)狭い範囲の出来事ではない、(2)容易に統御されるものではない、しかし、かと言って(3)人間をがんじがらめにす る絶望的なものでもない、という認識に到達しつつある。

もっともフーコーの理論が魅力的であればあるほど、そのエピゴーネンも多く登場しました。いわゆ る全部フーコーの議論で解釈して満足する連中のことである。

フーコーの権力論は、保健=健康の権力を考察する際には、最初の梯子であることを、くれぐれも忘 れず、フーコーよりももっと興味深い、保健=健康の権力を探究しよう。アシル・ムベンベは、フーコーの健康な人口を構成する生命に着目するバイオポリティクスには、それを裏打ちする死者のカウントと管理というネクロポリティクスという隠された概念があることを指摘している(→「アシル・ムベンベとネクロポリティクス」)。

| Biopower Biopower (or biopouvoir in French) is a term coined by French scholar, philosopher, historian, and social theorist Michel Foucault. It relates to the practice of modern nation states and their regulation of their subjects through "an explosion of numerous and diverse techniques for achieving the subjugations of bodies and the control of populations[clarification needed]".[1] Foucault first used the term in his lecture courses at the Collège de France,[2][3] and the term first appeared in print in The Will to Knowledge, Foucault's first volume of The History of Sexuality.[4] In Foucault's work, it has been used to refer to practices of public health, regulation of heredity, and risk regulation, among many other regulatory mechanisms often linked less directly with literal physical health. It is closely related to a term he uses much less frequently, but which subsequent thinkers have taken up independently, biopolitics, which aligns more closely with the examination of the strategies and mechanisms through which human life processes are managed under regimes of authority over knowledge, power, and the processes of subjectivation.[5] |

バイオパワー(フランス語でbiopouvoir) バイオパワー(フランス語でbiopouvoir)とは、フランスの学 者、哲学者、歴史家、社会理論家であるミシェル・フーコーによる造語である。近代国家の実践と、「肉体の服従と集団の統制を達成するための多種多様な技術 の爆発的増加[要解釈]」による臣民の規制に関するものである。 [1]フーコーはこの用語をコレージュ・ド・フランスの講義で初めて使用し[2][3]、この用語はフーコーの『セクシュアリティの歴史』の第1巻である 『知識への意志』で初めて印刷物として登場した[4]。 フーコーの著作では、公衆衛生の実践、遺伝の規制、リスクの規制、その他多くの規制メカニズムの中で、しばしば文字通りの身体的健康とはあまり直接的に結 びつかないものを指すのに使用されている。フーコーが使用する頻度ははるかに低いが、後続の思想家たちが独自に取り上げたバイオポリティクスという用語と 密接に関連しており、知識、権力、主体化のプロセスをめぐる権威の体制のもとで、人間の生命過程が管理される戦略やメカニズムの検討とより密接に連携して いる[5]。 |

| Foucault's conception For Foucault, biopower is a technology of power for managing humans in large groups; the distinctive quality of this political technology is that it allows for the control of entire populations. It refers to the control of human bodies through an anatomo-politics of the human body and biopolitics of the population through societal disciplinary institutions. Initially imposed from outside, whose source remains elusive to further investigation both by the social sciences and the humanities, and in fact, you could argue will remain elusive as long as both disciplines use their current research methods. Modern power, according to Foucault's analysis, becomes encoded into social practices as well as human behavior, as the human subject gradually acquiesces to subtle regulations and expectations of the social order. It is an integral feature and essential to the workings of—and makes possible the emergence of—the modern nation state, capitalism, etc.[6] Biopower is literally having power over bodies; it is "an explosion of numerous and diverse techniques for achieving the subjugation of bodies and the control of populations".[7] Foucault elaborates further in his lecture courses on biopower entitled Security, Territory, Population delivered at the Collège de France between January and April 1978: By this I mean a number of phenomena that seem to me to be quite significant, namely, the set of mechanisms through which the basic biological features of the human species became the object of a political strategy, of a general strategy of power, or, in other words, how, starting from the 18th century, modern Western societies took on board the fundamental biological fact that human beings are a species. This is what I have called biopower.[8] It relates to governmental concerns of fostering the life of the population, "an anatomo-politics of the human body a global mass that is affected by overall characteristics specific to life, like birth, death, production, illness, and so on.[9] It produces a generalized disciplinary society[10] and regulatory controls through biopolitics of the population".[11][12][13] In his lecture Society Must Be Defended, Foucault examines biopolitical state racism, and its accomplished rationale of myth-making and narrative. Here he states the fundamental difference between biopolitics[14] and discipline: Where discipline is the technology deployed to make individuals behave, to be efficient and productive workers, biopolitics is deployed to manage population; for example, to ensure a healthy workforce.[15] Foucault argues that the previous Greco-Roman, Medieval rule of the Roman emperor, the Divine right of kings, Absolute monarchy and the popes[16] model of power and social control over the body was an individualising mode based on a singular individual, primarily the king, Holy Roman emperor, pope and Roman emperor. However, after the emergence of the medieval metaphor body politic which meant society as a whole with the ruler, in this case the king, as the head of society with the so-called Estates of the realm and the Medieval Roman Catholic Church next to the monarch with the majority of the peasant population or feudal serfs at the bottom of the hierarchical pyramid. This meaning of the metaphor was then codified into medieval law for the offense of high treason and if found guilty the sentence of Hanged, drawn and quartered was carried out.[17][18] However, this was drastically altered in 18th century Europe with the advent and realignment of modern political power as opposed to the ancient world and Medieval version of political power. The mass democracy of the Liberal western world and the voting franchise was added to the mass population; liberal democracy and Political parties; universal adult suffrage-exclusively male at this time, then extended to women in Europe from 1906 (Finland) - 1971 (Switzerland, see Women's suffrage in Switzerland), and extending to people of African descent in America with the abolition of the infamous Jim Crow laws in 1964 (see Civil Rights Act of 1964 and Voting Rights Act of 1965). The emergence of the human sciences and its subsequent direction, during the 16th and 18th centuries, primarily aimed at the modern Western man and the society he inhabits, aided the development of Disciplinary institution[19][20][21] and furthermore, Foucault cites the human sciences, particularly the medical sciences, led to the advent of anatomo-politics of the human body, a biopolitics and bio-history of man.[22] A transition occurred through forcible removal of various European monarchs into a "scientific" state apparatus and the radical overhaul of judiciary practices coupled with the reinvention and division of those who were to be punished.[23] A second mode for seizure of power was developed as a type of power that was stochastic and "massifying" rather than "individualizing". By "massifying" Foucault means transforming into a population ("population state"),[24] with an extra added impetus of a governing mechanism in the form of a scientific machinery and apparatus. This scientific mechanism which we now know as the State "governs less" of the population and concentrates more on administrating external devices. Foucault then reminds us that this anatomo-biopoltics of the body (and human life) and the population correlates with the new founded knowledge of sciences and the 'new' politics of modern society, masquerading as liberal democracy, where life (biological life) itself became not only a deliberate political strategy but an economic, political and scientific problem, both for the mathematical sciences and the biological sciences–coupled together with the nation state.[25] |

フーコーの概念 フーコーにとって、バイオパワーとは、大きな集団における人間を管理するための権力技術であり、この政治技術の特徴は、集団全体のコントロールを可能にす ることである。この政治技術の特徴は、集団全体のコントロールを可能にすることである。バイオパワーとは、人体のアナトモ・ポリティクスによる人体のコン トロールと、社会的規律制度による集団のバイオポリティクスを指す。当初は外部から押し付けられたものであったが、その源は社会科学と人文科学の両分野が さらに調査することができないままであり、実際、両分野が現在の研究方法を用いる限り、とらえどころのないままであるとも言える。フーコーの分析によれ ば、現代の権力は、人間の行動だけでなく、社会的慣行にも符号化され、人間の主体が社会秩序の微妙な規制や期待に徐々に従うようになる。バイオパワーと は、文字通り身体に対する権力を持つことであり、「身体の服従と集団の統制を達成するための多種多様な技法の爆発」である[7]。フーコーは、1978年 1月から4月にかけてコレージュ・ド・フランスで行われた「安全保障、領土、人口」と題されたバイオパワーに関する講義の中で、さらに詳しく述べている: つまり、人間という種の基本的な生物学的特徴が、政治戦略や権力戦略全般の対象となった一連のメカニズム、言い換えれば、18世紀以降、近代西欧社会が、 人間が種であるという基本的な生物学的事実をどのように受け止めたかということである。これを私はバイオパワーと呼んでいる[8]。 それは人口の生命を育むという政府の関心事に関連しており、「誕生、死、生産、病気など、生命に特有の全体的な特性の影響を受ける地球規模の塊である人間 の身体のアナトモ・ポリティクス」[9]であり、「人口のバイオポリティクスを通じて、一般化された規律社会[10]と規制統制を生み出す」[11] [12][13]。フーコーは彼の講義『社会は守られなければならない』の中で、バイオポリティクス的な国家による人種差別と、神話づくりと物語というそ の達成された根拠を検証している。ここで彼は、生政治[14]と規律との根本的な違いを述べている: 規律が個人を行動させ、効率的で生産的な労働者にするために展開される技術であるのに対し、生政治は人口を管理するために展開される。 フーコーは、以前のグレコローマン、中世のローマ皇帝、王の神権、絶対君主制、ローマ教皇[16]による権力と身体に対する社会的支配のモデルは、主に 王、神聖ローマ皇帝、ローマ教皇、ローマ皇帝といった特異な個人を基盤とした個人化様式であったと論じている。しかし、中世のメタファーbody politicが出現した後は、支配者、この場合は国王を社会の長として、いわゆる領主団と中世ローマ・カトリック教会を君主の隣に置き、大多数の農民や 封建農奴を階層ピラミッドの底辺に置いた社会全体を意味するようになった。この比喩の意味は、その後、大逆罪として中世の法律に成文化され、有罪になると 絞首刑、絞首刑、四つ裂きの刑が執行された[17][18]。しかし、18世紀のヨーロッパでは、古代世界や中世の政治権力のバージョンとは対照的に、近 代的な政治権力の出現と再編成によって、これは劇的に変化した。リベラルな西欧世界の大衆民主主義と選挙権に加え、リベラルな民主主義と政党、成人普通選 挙-この時点では男性のみであったが、1906年(フィンランド)から1971年(スイス、スイスの女性参政権を参照)までヨーロッパで女性に拡大され、 1964年の悪名高いジム・クロウ法の廃止(1964年の公民権法と1965年の投票権法を参照)によってアメリカではアフリカ系の人々にも拡大された。 16世紀から18世紀にかけての人間科学の出現とそれに続く方向性は、主に西洋の近代的な人間と彼が住む社会を対象としており、規律制度の発展を助けた [19][20][21]。 [科学的な」国家機構へのヨーロッパの様々な君主の強制的な排除と、処罰されるべき人々の再発明と分断と結びついた司法の実践の根本的な見直しによって、 転換が起こった[23]。 権力の掌握のための第二の様式は、「個人化」ではなく確率的で「大衆化」するタイプの権力として開発された。大衆化」とはフーコーが人口(「人口国家」) への変容を意味しており[24]、さらに科学的な機械と装置というかたちで統治機構が追加された。私たちが現在国家として知っているこの科学的機構は、人 口を「より少なく」統治し、外部の装置を管理することに集中する。そしてフーコーは、この身体(と人間の生命)と人口のアナトモ・バイオポリティクスが、 科学が新たに確立した知識と、自由民主主義を装った近代社会の「新しい」政治と相関していることを思い起こさせる。 |

| Quotation And I think that one of the greatest transformations political right underwent in the 19th century was precisely that, I wouldn't say exactly that sovereignty's old right—to take life or let live—was replaced, but it came to be complemented by a new right which does not erase the old right but which does penetrate it, permeate it. To say that power took possession of life in the nineteenth century, or to say that power at least takes life under its care in the nineteenth century, is to say that it has, thanks to the play of technologies of discipline on the one hand and technologies of regulation on the other, succeeded in covering the whole surface that lies between the organic and the biological, between body and population. We are, then, in a power that has taken control of both the body and life or that has, if you like, taken control of life in general – with the body as one pole and the population as the other. What we are dealing with in this new technology of power is not exactly society (or at least not the social body, as defined by the jurists), nor is it the individual body. It is a new body, a multiple body, a body with so many heads that, while they might not be infinite in number, cannot necessarily be counted. Biopolitics deals with the population, with the population as a political problem, as a problem that is at once scientific and political, as a biological problem and as power’s problem I would like in fact like to trace the transformation not at the level of political theory, but rather at the level of the mechanisms, techniques, and technologies of power. We saw the emergence of techniques of power that were essentially centered on the body, on the individual body. They included all devices that were used to ensure the spatial distribution of individuals bodies (their separation, their alignment, their serialization, and their surveillance)and the organization, around those individuals, of a whole field of visibility. They were also techniques that could be used to take control over bodies. Attempts were made to increase their productive force through exercise, drill, and so on. They were also techniques for rationalizing and strictly economizing on a power that had to be used in the least costly way possible, thanks to whole system of surveillance, hierarchies, inspections, book-keeping, and reports-all the technology of labor. It was established at the end of the seventeenth century, and in the course of the eighteenth century.[26] |

引用 「19世紀に政治的権利が受けた最も大きな変革のひとつは、まさにそれ であったと思う。主権が持っていた古い権利、つまり生命を奪うか、あるいは生命を生かすかという権利が取って代わられたとは正確には言わないが、それは新 しい権利によって補完されるようになった。19世紀において権力が生命を所有するようになった、あるいは、19世紀において権力が少なくとも生命をその管 理下に置くようになった、と言うことは、一方では規律技術、他方では規制技術の戯れのおかげで、有機的なものと生物学的なもの、身体と集団の間に横たわる 全表面を覆うことに成功した、と言うことである。つまり私たちは、身体と生命の両方を支配する、あるいは生命全般を支配する権力の中にいるのである。この 新しい権力技術で私たちが扱っているのは、正確には社会(少なくとも法学者の定義する社会的身体)でもなければ、個人の身体でもない。それは新しい身体で あり、複数の身体であり、数は無限ではないかもしれないが、必ずしも数えることができないほど多くの頭部を持つ身体である。生政治学は、政治的問題として の人口、科学的であると同時に政治的な問題としての人口、生物学的な問題としての人口、そして権力の問題としての人口を扱う。私たちは、本質的に身体、個 人の身体を中心とした権力の技術の出現を見た。その中には、個人の身体の空間的な分布(分離、整列、連続化、監視)と、それらの個人を中心とした可視性の 場全体の組織化を保証するために使用されるあらゆる装置が含まれていた。それはまた、身体を支配するために使われる技術でもあった。運動や訓練などを通じ て生産力を高めようとした。また、監視、階層化、検査、帳簿管理、報告書など、あらゆる労働技術のおかげで、できるだけコストのかからない方法で使用しな ければならない権力を合理化し、厳しく節約するための技術でもあった。それは17世紀末から18世紀にかけて確立された[26]。」 |

Foucault argues that nation states, police, government, legal practices, human sciences and medical institutions have their own rationale, cause and effects, strategies, technologies, mechanisms and codes and have managed successfully in the past to obscure their workings by hiding behind observation and scrutiny. Foucault insists social institutions such as governments, laws, religion, politics, social administration, monetary institutions, military institutions cannot have the same rigorous practices and procedure with claims to independent knowledge like those of the human and 'hard' sciences, such as mathematics, chemistry, astronomy, physics, genetics, and biology.[27] Foucault sees these differences in techniques as nothing more than "behaviour control technologies", and modern biopower as nothing more than a series of webs and networks working its way around the societal body. However, Foucault argues the exercise of power in the service of maximizing life carries a dark underside. When the state is invested in protecting the life of the population, when the stakes are life itself, anything can be justified. Groups identified as the threat to the existence of the life of the nation or of humanity can be eradicated with impunity. |

制度と権力 フーコーは、国家、警察、政府、法律実務、人間科学、医療機関には、独 自の理論的根拠、原因と結果、戦略、技術、メカニズム、規範があり、過去において、観察と精査の陰に隠れてその働きを曖昧にすることに成功してきたと主張 する。フーコーは、政府、法律、宗教、政治、社会行政、貨幣制度、軍事制度などの社会制度は、数学、化学、天文学、物理学、遺伝学、生物学などの人間科学 や「ハード」サイエンスのような独立した知識を主張する厳格な実践や手続きを持つことはできないと主張している[27]。フーコーは、これらの技術の違い を「行動制御技術」にすぎないと見ており、現代のバイオパワーは、社会的身体の周囲で働く一連の網やネットワークにすぎないと見ている。 しかしフーコーは、生命を最大化するための権力の行使には暗い裏側があると主張する。国家が住民の生命を守ることに投資しているとき、つまり生命そのもの を賭けているとき、どんなことでも正当化されうる。国家や人類の存続を脅かすと見なされた集団は、平気で根絶やしにすることができる。 |

| If genocide is indeed the dream

of modern power, this is not because of the recent return to the

ancient right to kill; it is because power is situated and exercised at

the level of life, the species, the race, and the large-scale phenomena

of the population.[28] |

「ジェノサイドが現代の権力の夢であるとすれば、それは古代の殺人の権

利に最近回帰したからではなく、権力が生命、種、人種、人口という大規模な現象のレベルに位置づけられ、行使されるからである[28]。」 |

| Milieu intérieur Foucault concentrates his attention on what he calls the major political and social project, namely the Milieu, or the environment within. Foucault takes as his starting point the 16th century, continuing to the 18th century, with the milieu culminating into the founding disciplines of science, mathematics,[29] political economy and statistics.[30][31] Foucault makes an explicit point on the value of secrecy of government (arcana imperii, from the Latin which means secrecy of power, secrets of the empire, which goes back to the time of the Roman empire in the age of Tacitus) coined by Jean Bodin and was incorporated into a politics of truth. Foucault insists, in referring to the term 'public opinion' ('politics of truth'), that the concept of truth refers to the term 'regimes of truth'. He mentions a group called The Ideologues where the term Ideology first appears and is taken from.[32][33] Foucault argues that it is through 'regimes of truth' that raison d'état achieves its political and biological success.[34] Here the modern version of government is presented to the population in the national media—in the electronic media television and radio, and especially in the written press—as the modicum of efficiency, fiscal optimisation, political responsibility, and fiscal rigorousness. Thus, a public discourse of government solidarity emerges and social consensus is emphasised through these four points. This impression of joint solidarity is continuously reproduced through inherited political rationality, in turn giving the machine (Foucault uses the term Dispositif) of the State not only legitimacy but an air of invincibility from its main primary sources: reason, truth, freedom, and human existence. Foucault traces the first dynamics, the first historical dimensions, as belonging to the early Middle Ages. One major thinker whose work forms a parallel with Foucault's own is the Medieval historian Ernst Kantorowicz.[35][36][37][38] Kantorowicz mentions a Medieval device known as the body politic (the king's two bodies). This Medieval device was so well received by legal theorists and lawyers of the day that it was incorporated and codified into Medieval society and institutions (Kantorowicz mentions the term Corporation which would later become known to us as capitalism, an economic category).[39] Kantorowicz also refers to the Glossators who belonged to a well-known branch of legal schools in medieval Europe, experts in jurisprudence and law science, appeal of treason, The Lords Appellant and the commentaries of jurist Edmund Plowden[40] and his Plowden Reports.[41] In Kantorowicz' analysis, a Medieval Political theology emerged throughout the Middle Ages which provided the modern basis for the democratisation of the hereditary succession of a wealthy elite and for our own modern political hierarchical order (Politicians) and their close association with the wealthy nobility.[42] Primarily, this is the democratisation of Sovereignty, which is known in modern political terms as "Liberal democracy". Kantorowicz argues a Medieval triumvirate appears (with the support of the legal machine), a private enterprise of wealth and succession both supporting the fixed hierarchical order reserved exclusively for the nobility and their descendants, and the monarch and her/his heirs. Co-operation was needed by the three groups—the Monarchy, the Church, and the Nobility—in an uneasy Medieval alliance and, at times, it appeared fractious.[43][44] What is the reasoning behind the whole population subservience with the worshiping of state emblems, symbols and related mechanisms with their associates who represent the institutional mechanism (democratization of sovereignty); where fierce loyalty from the population is presented, in modern times as universal admiration for the president, the monarch, the Pope and the prime minister? Foucault would argue that while all the cost benefits were met by the newly founded urban population in the form of production and Political power, it is precisely this type of behaviour which enables social cohesion, and supports the raison dêtre of the Nation state as well as its capacity to "govern less." Foucault makes special note on the biological "naturalness" of the human species and the new founded scientific interest that was developing around not only with the species interaction with milieu and technology, but most importantly, technology operating as system not as so often portrayed by the political and social sciences which insisted on technology operating as social improvement. Both milieu, natural sciences and technology, allied with the characteristics surrounding social organization and increasingly the categorization of the sciences to help deal with this "naturalness" of milieu and of the inscription of truth onto nature. Due to Foucault's discussions with Georges Canguilhem,[45] Foucault notices that not only was milieu now a newly discovered scientific biological naturalness ever-present in Lamarckian Biology the notion (biological naturalness) was actually invented and imported from Newtonian mechanics (Classical mechanics) via Georges-Louis Leclerc, Comte de Buffon due to Buffon mentorship and friendship with Jean-Baptiste Lamarck and used by Biology in the middle of the 18th century borrowing from Newton the explanatory model of an organic reaction through the action of "milieu Newtonian" physics used by Isaac Newton and the Newtonians.[46] Humans (the species being mentioned in Marx) were now both the object of this newly discovered scientific and "natural" truth and new categorization, but subjected to it allied by laws, both scientific and natural law (scientific Jurisprudence), the state's mode of governmental rationality to the will of its population. But, most importantly, interaction with the social environment and social interactions with others and the modern nation state's interest in the populations well-being and the destructive capability that the state possess in its armoury and it was with the group who called themselves the économistes[47] (Vincent de Gournay, François Quesnay, François Véron Duverger de Forbonnais, and Anne-Robert-Jacques Turgot)[48][49] who continued with the rationalization of this "naturalness". Foucault notices that this "naturalness" continues and is extended further with the advent of 18th century political society with the new founded implement "population" and their (political population) association with raison d'état.[50] |

内なる環境 フーコーは、彼が主要な政治的・社会的プロジェクトと呼ぶもの、すなわち「ミリュー」(内的環境)に関心を集中させている。フーコーは16世紀を出発点と し、18世紀へと続き、ミリューは科学、数学、[29]政治経済学、統計学といった創設期の学問へと結実していく。フーコーは、「世論」(「真実の政 治」)という用語に言及しながら、真実の概念は「真実の体制」という用語を指すと主張している。フーコーは、レゾンデタートがその政治的・生物学的成功を 達成するのは「真実の体制」を通じてであると論じている[32][33] 。こうして、政府の連帯という言説が国民の間に生まれ、この4点を通じて社会的コンセンサスが強調される。この共同連帯の印象は、受け継がれた政治的合理 性によって継続的に再生産され、その結果、国家という機械(フーコーは「ディスポジティフ」という用語を使っている)に正当性を与えるだけでなく、理性、 真理、自由、人間存在という主要な一次資料から無敵の空気を与える。フーコーは、最初の力学、最初の歴史的次元を、中世初期に属するものとしてたどってい る。 フーコー自身の仕事とパラレルを形成する主要な思想家のひとりが、中世の歴史家エルンスト・カントロヴィッチである[35][36][37][38]。カ ントロヴィッチは、ボディ・ポリティック(王の二つの身体)として知られる中世の装置に言及している。この中世の装置は当時の法理論者や法学者によって非 常に高く評価され、中世の社会や制度に組み込まれ、成文化された(カントロヴィッチは後に資本主義という経済カテゴリーとして知られるようになるコーポ レーションという用語に言及している)[39]。カントロヴィッチはまた、中世ヨーロッパにおける法学や法学の専門家である有名な法学派の一派に属してい たグロッセーター(Glossator)、反逆罪の上訴、ロード・アペラント(The Lords Appellant)、法学者エドモンド・プラウデン(Edmund Plowden)の注釈書[40]、および彼のプラウデン・レポート(Plowden Reports)にも言及している。 [41] カントロヴィッチの分析によれば、中世政治神学は中世を通じて出現し、裕福なエリートの世襲を民主化し、現代の政治的階層秩序(政治家)と裕福な貴族との 緊密な関係のための近代的基礎を提供した。カントロヴィッチは、貴族とその子孫、そして君主とその相続人のためにのみ確保された固定的な階層秩序を支える 富と継承の私企業である中世の三位一体が(法制度の支援によって)出現したと主張する。王政、教会、貴族という3つのグループによる協力は、中世の不安な 同盟関係において必要であり、時には分裂しているように見えた[43][44]。 制度的メカニズム(主権の民主化)を代表する彼らの仲間とともに、国家の紋章、シンボル、関連するメカニズムを崇拝し、国民全体が従属する背景には、どの ような理由があるのだろうか。国民からの激しい忠誠心は、現代においては、大統領、君主、ローマ教皇、首相に対する普遍的な称賛として提示されている。 フーコーは、すべての費用便益は、生産と政治権力という形で、新たに創設された都市住民によって満たされたものの、まさにこの種の行動こそが、社会的結束 を可能にし、国民国家の存在意義と "より少ない統治 "能力を支えているのだと主張するだろう。 フーコーは、人間という種の生物学的な「自然性」と、環境とテクノロジーとの相互作用だけでなく、最も重要なこととして、社会的改善としてテクノロジーが 機能することを主張する政治科学や社会科学がよく描くようなシステムとしてではなく、システムとして機能するテクノロジーをめぐって展開された新たな科学 的関心について、特に言及している。環境、自然科学、技術の両方が、社会組織を取り巻く特性と連携し、環境と自然への真理の刻み付けの「自然性」に対処す るために、ますます科学のカテゴリー化が進んでいる。フーコーがジョルジュ・カンギレムと議論したことによって、[45]フーコーは、ミリューがラマルク 派の生物学において新たに発見された科学的な生物学的自然性であるだけでなく、その概念(生物学的自然性)が実際にはニュートン力学(古典力学)からジョ ルジュ=ルイ・ルクレールを通じて発明され、輸入されたものであることに気づく、 ビュフォンがジャン=バティスト・ラマルクに師事し、親交を深めていたことから、18世紀半ばの生物学では、アイザック・ニュートンとニュートン派が用い た「ニュートン的」物理学の作用による有機反応の説明モデルをニュートンから借用して使用された。 [人間(マルクスで言及されている種)は今や、この新たに発見された科学的で「自然な」真理と新たな分類の対象であると同時に、科学的な法則と自然法則 (科学的な法学)の両方の法則、すなわち国家による政府の合理性の様式とその住民の意志とが結びついた法則に服従していた。しかし、最も重要なことは、社 会環境との相互作用、他者との社会的相互作用、そして近代国民国家の住民の幸福に対する関心、そして国家がその武器として保有する破壊的能力であり、この 「自然性」の合理化を続けたのは、自らをエコノミスト[47]と呼ぶグループ(ヴァンサン・ド・グルネ、フランソワ・ケスネ、フランソワ・ヴェロン・デュ ヴェルジェ・ド・フォルボネ、アンヌ=ロベール=ジャック・チュルゴ)[48][49]であった。フーコーは、この「自然性」が18世紀の政治社会の到来 によって、新たに創設された「人口」という道具と彼ら(政治的人口)とレゾンデタットとの関連によって継続し、さらに拡張されていることに気づいている [50]。 |

| Biopolitics Foucault's lectures at the Collège de France Governmentality Necropolitics |

|

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Biopower |

★「生政治= バイオポリティクス」のエントリーの内容と同じもの |

| Biopolitics Biopolitics refers to the political relations between the administration of life and a locality's populations, where politics and law evaluate life based on perceived constants and traits. French philosopher Michel Foucault, who wrote about and gave lectures dedicated to his theory of biopolitics, wrote that it is "to ensure, sustain, and multiply life, to put this life in order."[1] |

生政治=バイオポリティクス 生政治とは、生命の管理と地域住民との政治的関係を指し、そこでは政治 と法が、認識された定数と形質に基づいて生命を評価する。フランスの哲学者であるミシェル・フーコーは、生政治の理論について執筆し、講義を行ったが、そ れは「生命を確保し、維持し、増殖させ、この生命を秩序づけること」であると書いている[1]。 |

| Notions of biopolitics Previous notions of the concept can be traced back to the Middle Ages in John of Salisbury's work Policraticus, in which the term body politic was coined and used. The term biopolitics was first used by Rudolf Kjellén, a political scientist who also coined the term geopolitics,[2] in his 1905 two-volume work The Great Powers.[3] Kjellén used the term in the context of his aim to study "the civil war between social groups" (comprising the state) from a biological perspective, and thus named his putative discipline "biopolitics".[4] In Kjellén's organicist view, the state was a quasi-biological organism, a "super-individual creature." The Nazis also subsequently used the term in the context of their racial policy, with Hans Reiter using it in a 1934 speech to refer to their concept of nation and state based on racial supremacy.[5] In contemporary US political science studies, usage of the term is mostly divided between a poststructuralist group using the meaning assigned by Foucault (denoting social and political power over life) and another group that uses it to denote studies relating biology and political science.[5] In the work of Foucault, biopolitics refers to the style of government that regulates populations through "biopower" (the application and impact of political power on all aspects of human life).[6][7] Morley Roberts, in his 1938 book Bio-politics argued that a correct model for world politics is "a loose association of cell and protozoa colonies".[5] Robert E. Kuttner used the term to refer to his particular brand of "scientific racism," as he called it, which he worked out with noted Eustace Mullins, with whom Kuttner co-founded the Institute for Biopolitics in the late 1950s, and also with Glayde Whitney, a behavioral geneticist. Most of his adversaries designate his model as antisemitic. Kuttner and Mullins were inspired by Morley Roberts, who was in turn inspired by Arthur Keith, or both were inspired by each other and either co-wrote together (or with the Institute of Biopolitics) Biopolitics of Organic Materialism dedicated to Roberts and reprinted some of his works.[8] In the work of Michael Hardt and Antonio Negri, biopolitics is framed in terms of anti-capitalist insurrection using life and the body as weapons; examples include flight from power and, "in its most tragic and revolting form", suicide terrorism, conceptualized as the opposite of biopower, which is seen as the practice of sovereignty in biopolitical conditions.[9] According to Professor Agni Vlavianos Arvanitis,[10][11][12] biopolitics is a conceptual and operative framework for societal development, promoting bios (Greek for "life") as the central theme in every human endeavor, be it policy, education, art, government, science or technology. This concept uses bios as a term referring to all forms of life on our planet, including their genetic and geographic variation.[13] |

生政治の概念 この概念に関する以前の概念は、中世に遡ることができ、ソールズベリーのジョンの著作『Policraticus』において、body politicという造語が使われた。生政治という用語は、地政学という用語も生み出した政治学者ルドルフ・ケレンによって、1905年の2巻からなる著 作『大国』の中で初めて使われた[2]。 [3] ケレンは、生物学的観点から(国家を構成する)「社会集団間の内戦」を研究するという彼の目的の文脈でこの用語を使用し、そのため彼の想定する学問分野を 「生物政治学」と命名した。[4] ケレンの有機主義的見解では、国家は準生物学的有機体であり、"超個体的生物 "であった。ナチスはその後、人種政策の文脈でもこの用語を使用しており、ハンス・ライターは1934年の演説において、人種至上主義に基づく国家と国家 の概念に言及するためにこの用語を使用している[5]。 現代のアメリカの政治学研究において、この用語の用法は、フーコーによって割り当てられた意味(生命に対する社会的・政治的権力を示す)を使用するポスト 構造主義のグループと、生物学と政治学に関連する研究を示すために使用する別のグループとにほとんど分かれている[5]。フーコーの研究において、生政治 は「生権」(政治権力の人間生活のあらゆる側面への適用と影響)を通じて集団を規制する政府のスタイルを指す[6][7]。 モーリー・ロバーツは1938年の著書『バイオポリティクス』の中で、世界政治の正しいモデルは「細胞や原生動物のコロニーの緩やかな連合体」であると主 張した[5]。ロバート・E・カットナーは、1950年代後半にカットナーがバイオポリティクス研究所を共同で設立した著名なユースタス・マリンズや、行 動遺伝学者のグレイデ・ホイットニーと共同で作り上げた、彼の言うところの「科学的人種差別主義」の特殊なブランドを指す言葉としてこの言葉を使用した。 彼の敵対者の大半は、彼のモデルを反ユダヤ主義的なものとしている。カットナーとマリンズはモーリー・ロバーツに触発され、モーリー・ロバーツはアー サー・キースに触発され、あるいは両者とも互いに触発され、ロバーツに捧げる『有機的唯物論の生政治学』を共同で(あるいは生政治研究所と共同で)執筆 し、彼の著作の一部を再版した[8]。 マイケル・ハートとアントニオ・ネグリの仕事において、生政治は生命と身体を武器とした反資本主義的な反乱という観点から組み立てられている。その例と しては、権力からの逃走や、「その最も悲劇的で反乱的な形態」である自殺テロリズムがあり、生政治的な状況における主権の実践と見なされる生権力の対極と して概念化されている[9]。 アグニ・ヴラヴィアノス・アルヴァニティス教授[10][11][12]によれば、生政治学は社会発展のための概念的かつ実践的な枠組みであり、政策、教 育、芸術、政府、科学、技術など、あらゆる人間の努力において中心的なテーマとしてビオス(ギリシャ語で「生命」の意)を推進するものである。この概念で は、遺伝的・地理的変異を含め、地球上のあらゆる形態の生命を指す言葉としてビオスを用いている[13]。 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Biopolitics |

|

| biopolitique Le terme biopolitique est un néologisme utilisé par Michel Foucault pour identifier une forme d'exercice du pouvoir qui porte, non plus sur les territoires mais sur la vie des individus, sur des populations, le biopouvoir. Il a été repris et développé depuis par Giorgio Agamben, Toni Negri et Roberto Esposito1. Biopolitique et discipline L'intégration du vivant dans la politique La « biopolitique » naît publiquement à Rio de Janeiro en octobre 1974, lors d'une série de cours sur « La médecine sociale ». Certains de ces cours ont été publiés et se trouvent dans les Dits et écrits de Michel Foucault : « La naissance de la médecine sociale », p. 207-2282 « L'incorporation de l'hôpital dans la technologie moderne », III, nº 229 2 Foucault recourt à un modèle, le différentiel de traitement des épidémies de lèpre et de peste, qui sera repris au Collège de France (le 15 janvier 1975), et qui se retrouve dans Surveiller et punir (inaugurant le chapitre « Le panoptisme »), publié au début de l'année 1975. À trois reprises en quelques mois, Foucault use de la même figure, à chaque fois différemment. Une constante toutefois : il y voit l'illustration du passage d'un type de pouvoir à un autre. À chaque fois, il relève que ce nouveau type de pouvoir prend en compte et s'exerce sur le corps et sur la vie, à la différence du plus ancien qui s'appliquait, selon le modèle juridique, sur les sujets. Dans l'attention à la vie de la population tel qu'il est mis en évidence dans la quarantaine, Foucault voit les débuts de ce qu'il va appeler la « biopolitique ». Il s'agit de la prise en compte progressive, par le pouvoir, de la vie de la population. Cela ne veut pas dire simplement un groupe humain nombreux, mais des êtres vivants traversés, commandés, régis par des processus, des lois biologiques. Une population a un taux de natalité, une pyramide des âges, une morbidité, elle peut périr ou bien au contraire se développer3. C'est une application à optimiser la force collective. Et c'est ainsi que l'on peut lire le dispositif de la quarantaine : maximaliser la vie de la population. De cette prise en compte de la population, de nouveaux types de problèmes vont se poser comme ceux de l'habitat, des conditions de vie dans une ville, de l'hygiène publique, de la modification du rapport entre natalité et mortalité. Foucault va tantôt mettre l'accent sur la prise en compte de la vie, et développer la genèse de la biopolitique, tantôt souligner la surveillance individualisante, et mettra en avant l'émergence du pouvoir disciplinaire. La biopolitique serait pour Michel Foucault, l'action concertée de la puissance commune sur l'ensemble des sujets, en tant qu'êtres vivants, sur la vie de la population, considérée comme une richesse de la puissance commune, devant être l'objet d'attention en vue de la faire croître et d'en accroître la vitalité. Lèpre et exclusion Au Moyen Âge, la lèpre se soigne par l'exclusion du lépreux. Considérée comme un châtiment de Dieu, la maladie inspire une véritable terreur. Au cours d'une cérémonie, la separatio leprosorum, le lépreux est déclaré mort civilement et exclu de la communauté. Dans certains diocèses, il assiste même, dissimulé, au simulacre de sa propre inhumation avant de rejoindre la léproserie. Cette exclusion, géographique, civile, de la communauté physique lui assure son inclusion, culturelle et divine. « Le pécheur qui abandonne le lépreux à sa porte lui ouvre le salut4. » Le lépreux part habiter l'espace qu'occupe la léproserie dans la géographie physique et sociale : aux portes de la ville. Au bord des villes, non pas à l'intérieur mais non plus exactement en dehors de l'espace social et humain. De même que son exclusion de l'ordre humain apporte au lépreux l'inclusion sotériologique (l'ouvre au salut), la léproserie insiste, dans sa visibilité marginale, à rappeler en permanence cette séparation et cette malédiction divine, la puissance du divin. La topographie qui met en rapport dialectique la ville et la léproserie répète la topologie de la relation du lépreux et de la communauté. Soit une séparation nette : la communauté d'un côté et de l'autre, sans contact, mais en rapport, la masse indistincte de ceux qui en ont été rejetés : les lépreux. Séparation, division binaire signent le souverain. Peste et surveillance Lorsque la peste se déclarait dans une ville, une série de mesures était donnée qu'il fallait suivre, « sous peine de la vie »5 qui visait à mettre la population sous la plus étroite surveillance possible. La ville et ses alentours étaient fermés (dans sa lecture, Foucault ne va pas tellement insister sur ce point), avec interdiction d'en sortir. Le territoire mis en quarantaine était partagé en districts, les districts étaient partagés en quartiers, puis dans ces quartiers on isolait les rues, et il y avait dans chaque rue des surveillants, dans chaque quartier des inspecteurs, dans chaque district des responsables de district et dans la ville elle-même soit un gouverneur nommé à cet effet, soit encore les échevins qui avaient reçu, au moment de la peste, un supplément de pouvoir6. Les animaux errants étaient tués. Chaque habitant devait se faire recenser. Une fois le recensement et le partage du territoire achevés, chacun devait s'enfermer chez soi, toutes les clefs étaient rassemblées. Plus personne n'avait le droit de sortir et de circuler dans la ville. Un dispositif était prévu pour l'alimentation (réserves faites, système d'approvisionnement par paniers et poulies pour les denrées périssables). Ville immobilisée. Dans ce territoire isolé, à cette population paralysée dans la quarantaine, on appliquait des mesures de surveillance quadrillée. « Plus personne ne pouvait circuler, à l'exception des inspecteurs, des soldats, des intendants et des “corbeaux” : des misérables devant porter les malades, enterrer les morts, nettoyer les lieux infectés, etc. dont la mort ne comptait pas. » Quotidiennement, les inspecteurs passaient devant chacune des maisons dont ils avaient la charge et chaque habitant devait se présenter à une fenêtre (si possible, une fenêtre spécifique pour chacun). Les présents étaient notés. Si quelqu'un ne se présentait pas à la fenêtre, c'est qu'il était malade, ou bien mort. Les inspecteurs avaient également pour tâche de surveiller que personne ne sortît et de noter tous les événements, toutes les réclamations, toutes les remarques. Chaque jour, ils transmettaient au chef de district l'ensemble des informations relevées. Vérification permanente de la vitalité de chacun dans la communauté figée. Émergence de la relation pouvoir/savoir. La population est captée par le pouvoir politique qui cherche à en surveiller et à maîtriser les comportements, par une prise de corps. On note les morts, les malades, les événements de toute sorte. La ville est immobilisée et la population soumise à un enregistrement continu de son état. Chacun est surveillé, contrôlé, en permanence. Bien que ces mesures exceptionnelles (pour le cas des pestes) aient pour but de stopper l'épidémie, c'est avant tout à l'utopie de la cité bien gouvernée, où le pouvoir d'Etat peut s'affranchir du système juridique et délibératif que renvoient pour Foucault de telles mesures. Cette utopie est radicalement différente de celle du "gouvernement de la lèpre" qui est celle d'une "société pure". Ainsi, la gouvernementalité de la peste semble poser une norme pour le dispositif disciplinaire. « Les mailles du pouvoir » En 1976, à Salvador de Bahia, Michel Foucault reprend l'analyse du fonctionnement réel du pouvoir à l'aide des catégories de biopolitique et de discipline (ou anatomo-politique) qu'il avait commencé deux ans plus tôt à Rio de Janeiro. Au regard des intérêts du capitalisme, le vieux « système de pouvoir » souverain présentait deux grands défauts. « … le pouvoir politique, tel qu'il s'exerçait dans le corps social, était un pouvoir très discontinu », trop de choses lui échappaient (la plupart des choses en réalité : des activités de contrebande, des délits, etc.) : les mailles étaient trop grandes. D'où une première préoccupation : réduire la taille de celles-ci. Comment « … passer d'un pouvoir lacunaire, global, à un pouvoir continu, atomique et individualisant : que chacun, que chaque individu en lui-même, dans son corps, dans ses gestes, puisse être contrôlé, à la place des contrôles globaux et de masse » ? « Le second grand inconvénient des mécanismes de pouvoir, tels qu'ils fonctionnaient dans la monarchie, est qu'ils étaient excessivement onéreux. » Le pouvoir « … était essentiellement pouvoir de prélèvement » : essentiellement percepteur et prédateur. Dans cette mesure, il opérait toujours une soustraction économique et, par conséquent, loin de favoriser et de stimuler le flux économique, il était perpétuellement son obstacle et son frein. D'où cette seconde préoccupation : « trouver un mécanisme de pouvoir tel que, en même temps qu'il contrôle les choses et les personnes jusqu'au moindre détail, il ne soit pas onéreux ni essentiellement prédateur pour la société, qu'il s'exerce dans le sens du processus économique lui-même »7. C'est à ces deux préoccupations que vont commencer de répondre les dispositifs disciplinaires et biopolitiques. Le dispositif de la quarantaine peut être compris comme une des premières tentatives de contrôle fin au niveau individuel. L'inconvénient étant son fort coût et l'arrêt de toute activité économique, paralysie de la ville. Comment alors concilier ce dispositif, parfait du point de vue de la surveillance individualisée, avec l'activité économique ? La réponse sera trouvée dans la mise en place des institutions disciplinaires qui, en opérant des sortes de quarantaines partielles mais de longue durée, distribueront, répartiront les dispositifs de contrôle, permettant la poursuite et même l'amélioration de l'activité économique. Les différentes institutions disciplinaires se raccordent par des réseaux de communication. Réseau de systèmes durs de contrôle. La direction que prend le pouvoir, qui correspond au passage d'un pouvoir monarchique à un pouvoir bourgeois, est : contrôler le plus finement possible, le plus économiquement possible, plus vite aussi, de façon à favoriser le développement économique. Les sociétés disciplinaires auraient atteint leur apogée au début du xxe siècle et un autre type de société serait en train de leur succéder, que Gilles Deleuze, en affirmant suivre Michel Foucault, nomme vers la fin de sa vie les « sociétés de contrôle ». |

バイオポリティクス バイオポリティクスという用語は、ミシェル・フーコーが、もはや領土ではなく個人や集団の生命に関わる権力行使の形態-バイオパワー-を特定するために用 いた新造語である。 その後、ジョルジョ・アガンベン、トニ・ネグリ、ロベルト・エスポジートらによって取り上げられ、発展してきた1。 生政治と規律 生者を政治に組み込む 生政治学」は1974年10月、リオデジャネイロで「社会医学」に関する一連の講義の中で公に誕生した。これらの講義の一部は出版され、ミシェル・フー コーの『Dits et écrits』に収録されている: 「La naissance de la médecine sociale」, pp. 「近代医療技術への病院の取り込み」、III、229頁 2 フーコーは、コレージュ・ド・フランスで再び取り上げられ(1975年1月15日)、1975年初頭に出版された『Surveiller et punir』(「Le panoptisme」の章の冒頭)に登場する、ハンセン病とペストの流行の差異治療というモデルを用いている。フーコーは数ヶ月のあいだに3度、同じ人 物を、その都度違った形で用いている。しかし、ある種の権力から別の権力への移行を示す図として、この図が用いられている。フーコーは毎回、この新しいタ イプの権力は、法的なモデルに従って主体に適用される旧来の権力とは異なり、身体と生命を考慮に入れ、それに対して行使されるものだと指摘する。 フーコーは、『検疫』の中で明らかになった住民の生活への注目の中に、彼が後に「生政治」と呼ぶことになるものの始まりを見た。これは、権力者が住民の生 活を徐々に考慮に入れることである。これは単に人間の大きな集団を意味するのではなく、生物学的なプロセスや法則によって支配され、管理され、統治される 生き物を意味する。人口には出生率、年齢ピラミッド、罹患率があり、滅びることもあれば、逆に発展することもある3。集団の力を最適化するためのアプリ ケーションなのだ。そして、これが検疫システムを読み解く方法である。人口を考慮に入れることで、住宅、都市における生活環境、公衆衛生、出生と死亡の比 率の変化など、新しいタイプの問題が生まれた。 フーコーは、生命を考慮に入れる必要性を強調し、生政治の起源を発展させることもあれば、個人化する監視を強調し、規律権力の出現を強調することもあっ た。 ミシェル・フーコーにとって、生政治とは、共通の権力が、すべての主体に対して、生物として、共通の権力の資産とみなされる集団の生命に対して行う協調的 な行動であり、その生命を成長させ、その活力を増大させるという観点から注目されるべき対象である。 ハンセン病と排除 中世では、ハンセン病はハンセン病患者を排除することで治癒した。ハンセン病は神からの罰と考えられ、真の恐怖を呼び起こした。separatio leprosorumとして知られる儀式では、ハンセン病患者は市民的に死亡したと宣言され、共同体から排除された。いくつかの教区では、ハンセン病患者 は、ハンセン病患者院に収容される前に、人目につかないように模擬埋葬にさえ参列する。物理的な共同体から地理的・民事的に排除されることで、文化的・神 的な包摂が保証されるのである。 「ハンセン病患者を門前に放置する罪人は、救いの扉を開く4」のである。 ハンセン病患者は、物理的・社会的な地理学上、ハンセン病患者の隔離施設が占める空間、すなわち都市の門の前で生活することになる。町のはずれで、社会 的・人間的空間の内側ではないが、外側でもない。ハンセン病患者が人間的秩序から排除されることで、救い主的包摂がもたらされるように、ハンセン病患者の コロニーは、その周縁的な可視性において、この隔離と神の呪い、神の力を絶えず想起させることを主張する。 町とハンセン病施設を弁証法的関係に置くトポグラフィーは、ハンセン病患者と共同体の関係のトポロジーを繰り返す。つまり、明確な分離である。一方は共同 体であり、もう一方は、接触はないが関係性はある、共同体から拒絶された人々の不鮮明な塊、すなわちハンセン病患者である。 分離と二項対立は、主権者の特徴である。 ペストと監視 町でペストが発生すると、「命に代えても」5 従わなければならない一連の措置が定められ、住民を可能な限り厳重な監視下に置くことを目的とした。街とその周辺は閉鎖され(フーコーはこの点にはこだ わっていない)、人々は外出を禁じられた。隔離された地域は地区に分けられ、地区は近隣に分けられ、その近隣では通りが隔離され、各通りに監視員が配置さ れ、各近隣に検査官が配置され、各地区に地区管理者が配置され、街自体にはこの目的のために任命された総督か、ペスト発生時に追加権限を与えられた市会議 員が配置された6。 野良動物は殺処分された。すべての住民は国勢調査を受けなければならなかった。国勢調査と領土の分割が完了すると、全員が家に鍵をかけ、すべての鍵を回収 しなければならなかった。誰も町を出たり移動したりすることは許されなかった。食料供給システム(備蓄、生鮮食料品のバスケットと滑車システム)が導入さ れた。 行き詰まった町 この隔離された地域では、検疫によって麻痺した人口を抱え、一連の監視措置が適用された。 「検査官、兵士、準州兵、そして「カラス」、つまり病人を運び、死者を埋葬し、感染地域を清掃しなければならなかった哀れな人々、その死者はカウントされ なかった。 検査官は毎日、担当する家々を回り、住人はそれぞれ窓口に出頭しなければならなかった(可能であれば、一人一人特定の窓口に)。出席者は記録された。誰か が窓口に来なければ、病気か死んでいることを意味した。検査官はまた、誰も建物から出ないようにし、すべての出来事、苦情、発言を記録する責任を負ってい た。毎日、彼らは集めたすべての情報を地区マネージャーに伝えた。 これは、凍結されたコミュニティの全員の活力を常にチェックするものであった。権力と知識の関係の出現 住民は政治当局に捕らえられ、政治当局は死体数を数えることによって住民の行動を監視し、コントロールしようとした。死、病気、あらゆる出来事が記録され た。都市は停止し、住民はその状態を記録され続けた。誰もが常に監視され、管理された。このような例外的な措置(疫病の場合)の目的は流行を食い止めるこ とだったが、フーコーにとって、このような措置は何よりもまず、国家権力が法的・熟議的システムから自らを解放できる、よく統治された都市のユートピアで あった。このユートピアは、「ハンセン病の政府」のそれとは根本的に異なっており、「純粋な社会」のそれである。このように、疫病の政府性は、懲罰装置の 基準を示しているように思われる。 「権力の網の目 1976年、ミシェル・フーコーはサルバドール・デ・バイアで、2年前にリオデジャネイロで始めたバイオポリティクスと規律(あるいはアナトモ・ポリティ クス)のカテゴリーを用いた権力の実際の運用の分析を再開した。 資本主義の利益という観点から見ると、旧来の主権的な「権力システム」には2つの大きな欠陥があった。 「君主制で機能していた権力機構の第二の大きな欠点は、過度に負担が大きかったことである。権力は「......本質的に賦課権力であった」:本質的に徴 税権力であり、略奪権力であった。この限りにおいて、権力は常に経済から差し引かれるものであり、その結果、経済の流れを促進するどころか、常に妨げ、減 速させるものであった。それゆえ、第二の関心事は、「物事や人々を細部に至るまで統制しながらも、社会にとって負担が大きくなく、本質的に捕食的でもな く、経済プロセスそのものを方向づけるために行使される権力のメカニズムを見出すこと」である。 規律と生政治的措置が対応し始めるのは、この2つの懸念に対してである。検疫制度は、個人レベルでのきめ細かな管理の最初の試みのひとつとみなすことがで きる。その欠点は、コストが高いことと、経済活動を停止させ、都市を麻痺させたことである。では、個人を監視するという観点からは完璧なこのシステムを、 経済活動とどのように調和させることができたのだろうか?その答えは、一種の部分的だが長期的な隔離を行うことで、管理メカニズムを分散させ、経済活動を 継続させ、さらには向上させることを可能にする懲罰機関を設立することにあった。さまざまな規律機関は、コミュニケーション・ネットワークで結ばれてい る。ハード・コントロール・システムのネットワークである。 規律と生政治的措置が対応し始めたのは、この2つの懸念のためであった。検疫制度は、個人レベルでのきめ細かな管理の最初の試みのひとつとみなすことがで きる。その欠点は、コストが高いことと、経済活動を停止させ、都市を麻痺させることであった。では、個人を監視するという観点からは完璧なこのシステム を、経済活動とどのように調和させることができたのだろうか?その答えは、一種の部分的だが長期的な隔離を行うことで、管理メカニズムを分散させ、経済活 動を継続させ、さらには向上させることを可能にする懲罰機関を設立することにあった。さまざまな規律機関は、コミュニケーション・ネットワークで結ばれて いる。ハード・コントロール・システムのネットワークである。 君主的権力からブルジョア的権力への移行に対応する権力の方向性は、経済発展を促進するために、可能な限り細かく、可能な限り経済的に、可能な限り迅速に 統制することであった。 規律社会は20世紀初頭にその頂点に達したが、現在は、ミシェル・フーコーの足跡をたどるジル・ドゥルーズがその生涯の終わりにかけて「統制社会」と呼ん だ、別のタイプの社会に引き継がれつつある。 |

| https://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Biopolitique |

|

| biopouvoir Le biopouvoir est un type de pouvoir qui s'exerce sur la vie : la vie des corps et celle de la population. Selon Michel Foucault, il remplace peu à peu le pouvoir monarchique de donner la mort1. L'exercice de ce pouvoir constitue un gouvernement des hommes ; avant de s'exercer à travers les ministères de l'État, il aurait pris racine dans le gouvernement des âmes exercé par les ministres de l'Église. Les sujets du pouvoir exercé par les pasteurs de l'Église apprenaient à se considérer comme des brebis conduites par un berger. Le berger exerçait un pouvoir sur un troupeau de brebis, un troupeau d'âmes qu'il avait pour mission de sauver, c'est-à-dire de conduire au salut, plutôt que sur la population de corps de l'État-nation. Mais le fonctionnement de cette manière de pouvoir, proprement gouvernementale, restera la même, à travers l'Église ou l'État moderne : il est à la fois globalisant (le troupeau, la population) et individualisant (la brebis, le corps). Avec la Réforme, dès lors que naît la raison d'État et que plusieurs souverains chrétiens se déconnectent radicalement de l'Église (surtout en Allemagne et en Angleterre), le biopouvoir s'imbriquera, toujours selon Foucault, à l'exercice du pouvoir souverain. Dans cette version politique, étatique, le biopouvoir prendra en charge la vie, non plus des âmes, mais des hommes, avec d'un côté le corps (pour le discipliner) et d'un côté la population (pour la contrôler). L'élément commun au corps et à la population, c'est la norme. La norme statistique. C'est elle qui fait en sorte que ce biopouvoir s'exerce, de manière rationnelle, à la fois sur un ensemble statistique (une collectivité) et sur un individu/un particulier. Biopolitique Article détaillé : Biopolitique. Le biopouvoir, dans sa version politique, s'exerce d'abord via la prise en compte des êtres humains en tant qu'espèces vivantes; puis via leur milieu de vie, leur milieu d'existence. Par exemple, des épidémies de peste ont été liées à des problèmes de marécages et toute une politique d'hygiène publique s'est alors mise en place. Les effets de la ville sur la natalité, la mortalité, la vieillesse de la population ont été analysés. Avec l'industrialisation, la vieillesse, les accidents de travail et les infirmités de guerre posent le problème de l'individu qui tombe hors du champ de capacité au travail. Des mécanismes d'assurance et d'épargne visent à résoudre ce problème. Sont créées des caisses d'épargne et d'assurance collectives, des institutions médicales, des caisses de secours, des assurances-santé. L'industrialisation et la médecine publique ont suscité une véritable explosion démographique. Par conséquent, des mécanismes visant à réguler le mouvement des peuples se sont développés — des mécanismes statistiques2. Certains travaux universitaires s'inscrivent dans la lignée de ceux de Michel Foucault et questionnent le lien du biopouvoir à l'émergence et à la gestion politique du VIH-Sida. La chercheuse Florence Lhote avance ainsi la mise en crise du "biopouvoir" à la faveur de ce qu'elle a appelé "l'événement-Sida" dans les années 90 dans l'article "Genre et genres: le VIH par ses récits"3. |

バイオパワー バイオパワーとは、生命に対して行使される権力の一種であり、肉体の生命と住民の生命である。ミシェル・フーコーによれば、この権力は次第に、死を与える 君主的権力に取って代わりつつある1。国家の省庁を通じて行使される前は、教会の聖職者によって行使される魂の統治に根ざしていた。 教会の牧師たちによって行使された権力の臣民たちは、自分たちを羊飼いに導かれた羊のように見ることを学んだ。羊飼いは、国民国家の肉体の群れに対してで はなく、羊の群れ、すなわち、救うこと、すなわち救いに導くことを使命とする魂の群れに対して権力を行使したのである。それはグローバル化(群れ、人口) であり、個別化(羊、身体)である。 宗教改革によって国家という理性が生まれ、いくつかのキリスト教の君主が教会から根本的に切り離されたとき(特にドイツとイギリスにおいて)、バイオパ ワーは、やはりフーコーによれば、君主権力の行使と絡み合うようになった。 この政治的、国家主義的なバージョンでは、バイオパワーはもはや魂の命ではなく、人間の命を管理することになり、一方では身体(それを規律する)を、他方 では人口(それを管理する)を管理することになる。 身体と集団の共通要素は規範である。統計的規範である。この規範こそが、統計的全体(集団)と個人/私的個人の両方に対して、バイオパワーが合理的に行使 されることを保証するのである。 生政治 詳細記事: 生政治。 政治版バイオパワーは、第一に生物種としての人間を考慮することによって、第二に人間が生活する環境を考慮することによって行使される。例えば、ペストの 流行は湿地帯の問題と関連づけられ、公衆衛生政策が実施された。 都市が人口の出生率、死亡率、老齢率に及ぼす影響も分析された。工業化に伴い、老齢、労働中の事故、戦時中の障害が、もはや働くことのできない個人の問題 となった。保険や貯蓄制度は、この問題を解決することを目的としていた。集団貯蓄や保険基金、医療機関、救済基金、健康保険制度が創設された。 工業化と公的医療は、まさに人口爆発をもたらした。その結果、人々の移動を調整するメカニズム、すなわち統計メカニズムが開発された2。 ミシェル・フーコーの足跡をたどり、バイオパワーとHIV-AIDSの出現と政治的管理との関連性を問う学術研究もある。研究者フローレンス・ローテは、 論文 「Genre et genres: le VIH par ses récits 」3(ジェンダーとジャンル:HIVの物語を通して)の中で、1990年代の「エイズの出来事」と呼ばれるものによって「バイオパワー」が危機に陥ったと 論じている。 |

| https://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Biopouvoir |

★ネクロポリティクス[Necropolitics]

奴隷船の内部

| Necropolitics

is a sociopolitical theory of the use of social and political power to

dictate how some people may live and how some must die. The deployment

of necropolitics creates what Achille Mbembe calls deathworlds, or "new

and unique forms of social existence in which vast populations are

subjected to living conditions that confer upon them the status of the

living dead."[1] Mbembe, author of On the Postcolony, was the first

scholar to explore the term in depth in his 2003 article,[2] and later,

his 2019 book of the same name.[1] Mbembe identifies racism as a prime

driver of necropolitics, stating that racialized people's lives are

systemically cheapened and habituated to loss.[1] |

ネクロポリティクスとは、ある人々がどのように生き、ある人々がどのよ

うに死ななければならないかを規定するために、社会的・政治的権力を行使するという社会政治理論である。ネクロポリティクスの展開は、アシル・ムベンベが

言うところの「死の世界」、すなわち「膨大な人口が、生ける屍の地位を与える生活条件にさらされる、新しくユニークな社会的存在の形態」を生み出す。

1]

『ポストコロニーについて』の著者であるムベンベは、2003年の論文[2]、その後2019年に出版した同名の著書において、この用語を深く探求した最

初の学者である。

ムベンベは、人種差別がネクロポリティクスの主要な推進力であるとし、人種差別を受けた人々の生活が制度的に安っぽくされ、喪失に慣らされていると述べて

いる[1]。 |

| Concept Necropolitics is often discussed as an extension of biopower, the Foucauldian term for the use of social and political power to control people's lives. Foucault first discusses the concepts of biopower and biopolitics in his 1976 work, The Will to Knowledge: The History of Sexuality Volume I.[3] Foucault presents biopower as a mechanism for "protecting", but acknowledges that this protection often manifests itself as subjugation of non-normative populations.[3] The creation and maintenance of institutions that prioritize certain populations as more valuable is, according to Foucault, how population control has been normalized.[3] Mbembe's concept of necropolitics acknowledges that contemporary state-sponsored death cannot be explained by the theories of biopower and biopolitics, stating that "under the conditions of necropower, the lines between resistance and suicide, sacrifice and redemption, martyrdom and freedom are blurred."[2] Jasbir Puar assumes that discussions of biopolitics and necropolitics must be intertwined, because "the latter makes its presence known at the limits and through the excess of the former; [while] the former masks the multiplicity of its relationships to death and killing in order to enable the proliferation of the latter."[4] Mbembe was clear that necropolitics is more than simply a right to kill (Foucault's droit de glaive). While his view of necropolitics does include various forms of political violence such as the right to impose social or civil death, and the right to enslave others, it is also about the right to expose other people (including a country's own citizens) to mortal danger and death.[2] Cultural theorist Lauren Berlant calls this gradual and persistent process of elimination slow death.[5][6] According to Berlant, only specific populations are "marked out for wearing out"[7] and the conditions of being worn out and dying are intimately linked with "the ordinary reproduction of [daily] life."[8] Necropolitics is a theory of the walking dead, in which specific bodies are forced to remain in suspended states of being located somewhere between life and death. Mbembe provided a way of analyzing these "contemporary forms of subjugation of life to the power of death."[2] He utilized examples of slavery, apartheid, the colonization of Palestine and the figure of the suicide bomber to illustrate differing forms of necropower over the body (statist, racialized, a state of exception, urgency, martyrdom) and how this reduces people to precarious life conditions.[2] According to Marina Gržinić, necropolitics precisely defines the forms taken by neo-liberal global capitalist cuts in financial support for public health, social and education structures. To her, these extreme cuts present intensive neo-liberal procedures of ‘rationalization’ and ‘civilization’.[9] |

概念 ネクロポリティクスは、しばしばバイオパワーの延長として議論される。バイオパワーとは、人々の生活をコントロールするための社会的・政治的権力の行使を 意味するフーコー用語である。フーコーは1976年の著作『性の歴史:第1巻:知への意志(The History of Sexuality, Volume I)』の中で、バイオパワーとバイオポリティクスの概念について初めて論じている: フーコーはバイオパワーを「保護」のためのメカニズムとして提示しているが、この保護がしばしば非規範的な集団の服従として現れることを認めている [3]。フーコーによれば、特定の集団をより価値あるものとして優先させる制度の創設と維持は、人口抑制がいかにして常態化されてきたかということである [3]。 ムベンベのネクロポリティクスの概念は、現代の国家による死がバイオパワーやバイオポリティクスの理論では説明できないことを認め、「ネクロパワーの条件 下では、抵抗と自殺、犠牲と贖罪、殉教と自由の境界線は曖昧である」と述べている。 ジャスビール・プアーは、「後者(=ネクロパワー)は前者(= バイオパワー)の限界において、また過剰な存在を通して、その存在を知らしめるものであり、一方、前者は後者の増殖を可能にする ために、死と殺戮との関係の多様性を覆い隠すものである」[4]から、生政治とネクロポリティックスの議論は絡み合わなければならないと仮定している。 ムベンベは、ネクロポリティクスが単なる殺人の権利(フーコーのdroit de glaive [剣の権利])以上のものであることを明確にしていた。彼の考えるネクロポリティクスには、社会的あるいは市民的な死を課す権利や他者を奴隷化する権利な ど、さまざまな政治的暴力の形態が含まれる一方で、他者(自国民を含む)を致命的な危険や死にさらす権利のことでもある。 [2] 文化理論家のローレン・バーラントは、この緩やかで持続的な排除のプロセスを緩慢な死と呼んでいる[5][6]。 バーラントによれば、特定の集団だけが「消耗するようにマークされている」[7]のであり、消耗して死ぬという条件は「(日常)生活の通常の再生産」と密 接に結びついている[8]。 ネクロポリティクスとは、特定の身体が生と死の狭間に位置する宙吊りの状態に留まることを余儀なくされる、歩く死者の理論である。ムベンベは、このような 「生を死の力に服従させる現代の形態」を分析する方法を提供した[2]。彼は、奴隷制、アパルトヘイト、パレスチナの植民地化、自爆テロ犯の姿を例に挙 げ、身体をめぐるネクロパワーのさまざまな形態(国家主義、人種差別、例外状態、緊急性、殉教)と、それがいかに人々を不安定な生活状況に追いやるかを説 明した[2]。 マリナ・グルジニッチによれば、ネクロポリティクスは、ネオリベラルなグローバル資本主義による公衆衛生、社会、教育構造への財政支援削減の形態を正確に 定義している。彼女にとって、こうした極端な削減は、「合理化」と「文明化」の集中的な新自由主義的手続きを示している[9]。 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Necropolitics |

続きは「ネクロポリティクス」を参照 |

★

リンク

文献

その他の情報(以下は、ジャンクヤード)

***

フーコーの思想的展開において、重要なことは、コレージュ・ド・フランスでの1975- 1976年の講義「社会は防衛しなければならない」(Il faut deferndre la societe)[同名のタイトルで筑摩書房刊、2007年]につきると言えます。

フーコーの主張がくっきりと前期/後期と分かれるのかについては、私は専門家ではありませんの で、それほど興味はありません。しかし、この講義が終わった年(1976年)に出版される『性の歴史1』から、続刊が発刊されるまでの8年間のブランク に、後期フーコーの思想で表象されるさまざまな著作が登場します。【以下の表を参照】

「社会は防衛しなければならない」という講義録は、一見ばらばらな授業の集まりのようにも感じま す。思想の系譜学と権力論についての講義(1976年1月7日)、戦争論・生権力論・規律実践や人間科学についての多様なアイディアの披瀝(1月14 日)、クラウゼビッツや権力の弁証法(1月21日)、人種間戦争(1月28日)、ホッブス「リヴァイアサン」論(2月4日)、ブーランヴィリエと文書に代 表される歴史知の話(2月11日)、引き続きブーランヴィリエ論(2月18日、2月25日、3月3日)、国家の統一とナシオン(3月10日)、お世辞にも 大団円とは言えないが魅力的な生権力論(3月17日)です。

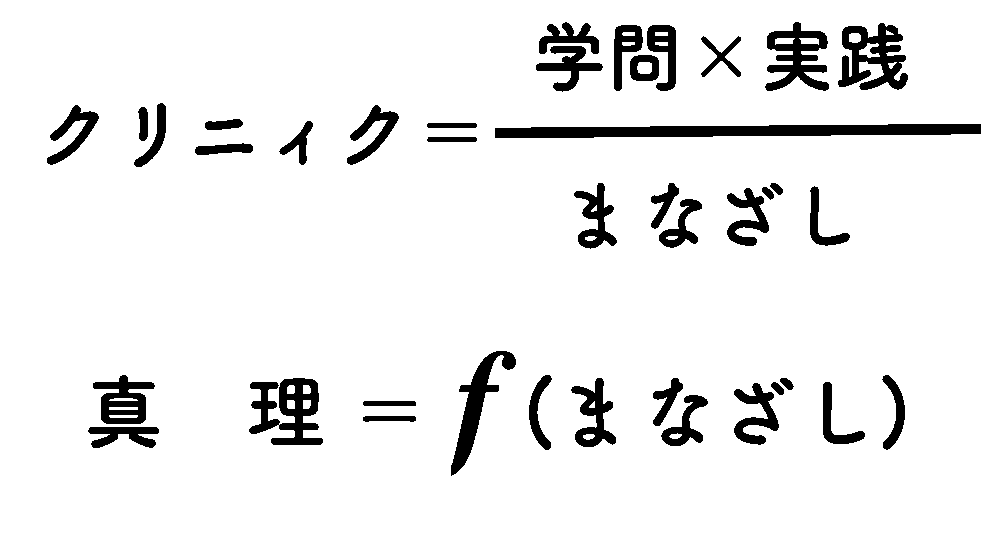

この1976年にはフーコーの前期と後期をブリッジする重要な著作『監視と懲罰』(邦訳『監獄の 誕生』)——ただし冒頭のレトリックはその13年前の『臨床の誕生』を彷彿させる——が公刊されています。

フーコーはこの講義のなかで、自分が追求してきたことは首尾一貫しているが、今までそれほど意識 していなかった議論すなわち生権力論がこの頃徐々に浮かびあがってきたことを吐露しています。

もしフーコーを、たんなる強力な知的権威として引用紹介してそれで安心するというむき(=研究 者)には、不用な話ですが、オリジナリティのある生権力をもってフーコーの思想の真の独自性が発揮されたと考える奇特な研究者にとっては、この時期のフー コーの考え方を追いかけることは大変魅力です。

またホッブス論に異様な興味をもつことから、生権力(bio-politic)はリヴァイアサン における身体政治論(body-politic)の地口的転倒として使ったとも言えます。

さらに蛇足として言えば、スティーブン・シェイピンとサイモン・シェーファー『リヴァイアサンと 真空ポンプ』(1986)やそれに触発されて書かれたブルーノ・ラトゥール『私たちは近代であったことはない』(1993)における、社会科学と自然科学 おける「真理」の証明という議論に連なるものでもあります。

***

■リンク

◎思考集成(→思考集成リスト)(完全リストはこちら)番号はエッセイの通し番号

第6巻(1976-77) 『セクシュアリテ/真理』

◎講義集成(筑摩で刊行中)

1976『監視と懲罰』(1976)『知への意思』(性の歴史1,1976)

1984『快楽の活用』(性の歴史2,1984)『自己へのケア』(性の歴史3, 1984)

◆ 権力について考える

M・フーコー『臨床医学の誕生』神谷美恵子訳、みすず書房、1969年

名訳の誉れ高い——ユマニスト的曲解があると言われるがここでは論評は避ける——が、 ho^pital を病院と施療院と訳し分けたり、comfiguration, constellationをゲシュタルトとするなど、読むときには、もう一ひねりしないとならないので、留意する。

M・フーコー「健康を語る権力」(『ミッシェル・フーコー1926-1984 権力・知・歴 史』新曜社、1984年)

M・フーコー『知への意志』(『性の歴史』の後期フーコー3部作のひとつ)

富永茂樹『健康論序説』河出書房

健康の社会化、社会の健康化という二重の過程が市民社会において強力な力を発揮する。

簡単な著作目録

- 『精神疾患とパーソナリティ』(中山元・訳、筑摩書房[文庫])Maladie mentale et Personnalit・ Paris: PUF, 1954.

- 『精神疾患と心理学』(神谷美恵子・訳、みすず書房) Maladie mentale et Psychologie (Paris: PUF, 1962). = second and extensively revised edition of Maladie mentale et Personnalte

- 『臨床医学の誕生』(神谷美恵子・訳、みすず書房) Naissance de la clinique: une archaologie du regard m仕ical (Paris: PUF, 1963).

- 『レーモン・ルーセル』(豊崎光一・訳、法政大学出版局)Raymond Roussel. (Paris: Gallimard, 1963), date of issue May 1963.

- 『言葉と物』(渡辺一 民ほか訳、新潮社)Les Mots et les Choses. Une archaologie des sciences humaines. Paris 1966.

- 『知の考古学』(中村雄一郎訳、河出書房新社) L'Archaologie du savoir (Paris: Gallimard, March 1969).

- 『言説表現の秩序』(中村雄一郎訳、河出書房新社) L'ordre du discours (Paris, Gallimard, 1971)

- 『狂気の歴史:古典主義時代における』(田村俶訳、新潮社)Histoire de la folie a l'age classique. Gallimard, 1972

- 『監獄の誕生』Surveiller et punir, naissance de la prison (Paris: Gallimard, February 1975).

- 『性の歴史 1権力への意志』Histoire de la sexualit・1. La volonte de savoir (Paris: Gallimard, 1976).

- [未訳]Le désordre des familles : lettres de cachet des Archives de la Bastille au XVIIIe siècle / présenté par Arlette Farge et Michel Foucault, [Paris] : Gallimard, Julliard , c1982. - (Collection Archives ; 91)

- 『性の歴史 2快楽の活用』Histoire de la sexualite II, L'usage des plaisirs (Paris: Gallimard, 1984)

- 『性の歴史 3自己への配慮』Histoire de la sexualite III, Le souci de soi (Paris: Gallimard, 1984)

健康というものが権力性をもつ場合、それが最もよく発動されているのは、病気であるというこ とを<強制的>に忘れさせようとする作用においてである。これを、健康による<病気の組織的忘却>の作用と呼んでおこう(2000.03.16 M.ikeda)。

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆