未開社会?だから何なんだよぅ?!

Primitive society? so what?

☆ このページは、頑迷な文化人類学者、民族学者、考古学者などが使う「未開社会(primitive society)」という概念がもはや、現代社会を理解するために、何の役にも立たないのに、使い続けているという「自己反省の無さ」を告発するページで ある。そして、その理由を考え、その代替語が見つからない時に、文化人類学、民族学、考古学という学問は、それまでおこなってきた、この「未開社会」の概 念に依存せず、これまで以上に良識あるサイエンスとしての、位置を維持することができるのかについて考察する。まずは、未開社会(primitive society)に関する用法を整理することである。なお、ウィキペディア(英語)は、未開社会(primitive society)の概念がもはや現代人の語彙として使えないことを見越してか?その項目がみつからない(見つけた人は教えてほしい)。

| This

article may be a rough translation from German. It may have been

generated, in whole or in part, by a computer or by a translator

without dual proficiency. Please help to enhance the translation. The

original article is under "Deutsch" in the "languages" list. |

【注意書き】この記事はドイツ語からの粗い翻訳である可能性がある。全体または一部が、コンピュータまたは二か国語に堪能でない翻訳者によって生成された可能性がある。翻訳の向上にご協力ください。原文は「languages」リストの「Deutsch」の下にある。 |

| Urgesellschaft

(meaning "primal society" in German) is a term that, according to

Friedrich Engels,[1] refers to the original coexistence of humans in

prehistoric times, before recorded history. Here, a distinction is made

between the kind of Homo sapiens as humans, who hardly differed from

modern humans biologically (an assertion disputed by anthropology), and

other representatives of the genus Homo such as the Homo erectus or the

Neanderthal. Engels claimed "that animal family dynamics and human

primitive society are incompatible things" because "the primitive

humans that developed out of animalism either knew no family at all or

at most one that does not occur among animals".[1] The U.S.

anthropologist Lewis Henry Morgan and translations of his books also

make use of the term.[2] In specificity, this long period of time is not directly accessible through historical sources. Nevertheless, in archaeology, the study of material cultures provides a variety of opportunities to gain a better understanding of this period, work that is likewise present in sociobiology and social anthropology, and in religious studies through the analysis of prehistoric mythologies. |

Urgesellschaft

(ドイツ語で「原始社会」の意)は、フリードリヒ・エンゲルスによると、[1]有史以前の先史時代に人間が共存していた時代を指す言葉である。ここでは、

生物学的には現代人とほとんど変わらないホモ・サピエンス(人類)と、ホモ・エレクトスやネアンデルタール人などのホモ属の他の代表種とを区別している。

エンゲルスは、「動物的な性質から進化した原始人間は、家族という概念をまったく持たないか、せいぜい動物には見られないような家族しか持たない」ため、

「動物の家族と人間の原始社会は両立しない」と主張した[1]。米国の人類学者ルイス・ヘンリー・モーガンと彼の著作の翻訳でも、この用語が使用されてい

る[2]。 具体的には、この長い期間は歴史的な資料から直接的に知ることはできない。しかし、考古学では、物質文化の研究により、この時代をより深く理解する機会が 数多くある。また、社会生物学や社会人類学、さらには先史時代の神話を分析する宗教学においても、同様の研究が行われている。 |

|

Image of a horse from the Lascaux caves made by the Cro-Magnon peoples at their hunting route in the Stone age |

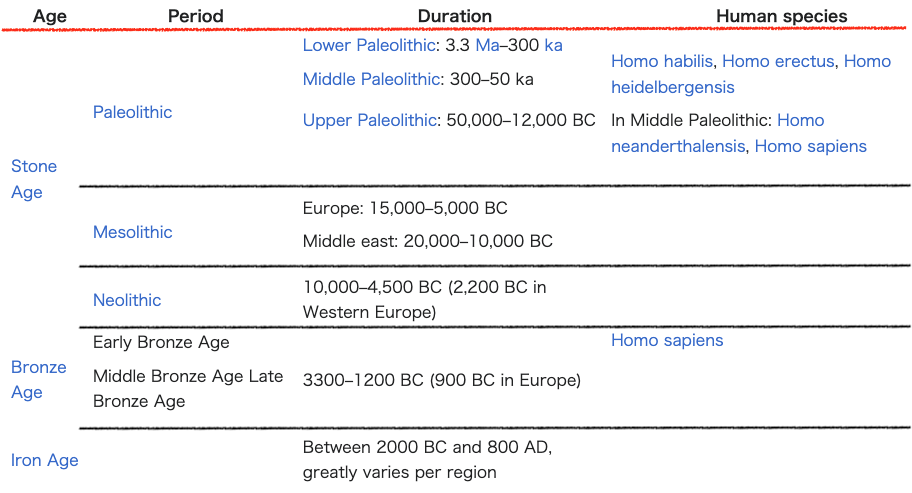

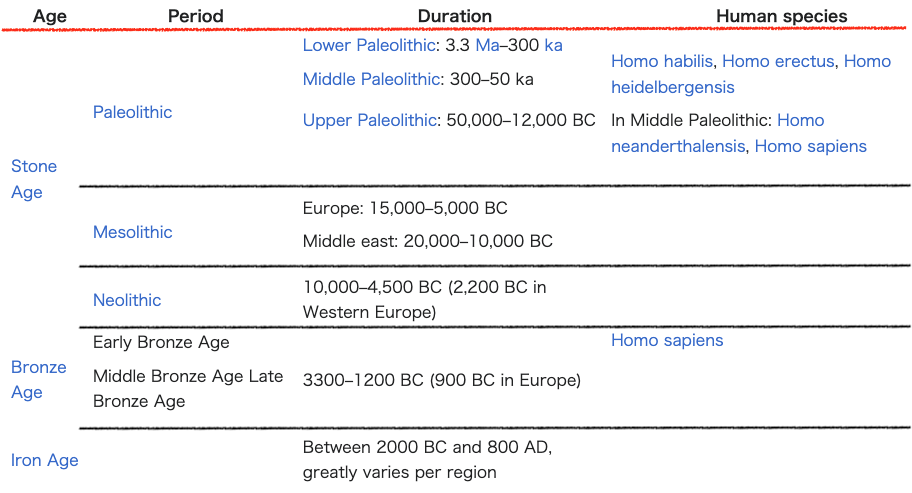

| Archaeological classification The so-called primitive society, or more appropriately, the primitive societies, probably span by far the longest period in the history of mankind to date, more than three million years, while other forms of society have existed and continue to exist for only a relatively short period in comparison (less than 1 percent of the period). The Stone Age is an archaeological term for the period in which stone tools (fist wedges) are the oldest chronologically classifiable and roughly datable finds.[3] Other, even older tools and objects made of natural or animal materials (wood, bones, skins) decayed and did not survive. This Stone Age also includes the development of new social structures about 20,000 to 6,000 years ago. Generally, the advent of arable farming and livestock rearing is considered to be the transition to the New Stone Age and the end of this phase. The Neolithic Revolution was followed in some areas by the Bronze Age (around 2200 to 800 BC), but in some cases ran in parallel.  |

考古学上の分類 いわゆる原始社会、あるいはより正確に言えば原始的社会は、おそらく人類史上最も長い期間、300万年以上続いたと考えられる。一方、他の社会形態は、それに比べると比較的短い期間しか存在しておらず(その期間の1%未満)、現在も存在している。 石器時代とは、考古学用語で、石器(握りこぶし形石器)が年代的に分類でき、おおまかに年代が特定できる最古の遺物である時代を指す[3]。それよりも古 い、自然素材や動物素材(木、骨、皮)でできた道具や物品は腐敗して現存していない。この石器時代には、約2万年から6000年前に新しい社会構造が発達 したことも含まれる。一般的に、耕作と家畜飼育の登場は新石器時代への移行とこの段階の終わりと考えられている。新石器革命の後、一部の地域では青銅器時 代(紀元前2200年~紀元前800年頃)が続いたが、並行して進んだ地域もある。  |

| A

society is formed by different-sized social groups acting together. At

different times in history, as well as in different climates and

ecozones, human societies were quite different. The gradual dispersal of early human groups (estimated at 1 to 10 kilometers per year) initially placed few demands on them and their generational succession-they did not perceive any changes, especially in equatorial regions. However, drastic environmental changes such as ice and warm periods, to which the migrants were exposed in the target area, caused new forms of adaptation with corresponding social structures. Food gathering and weather protection as well as the use of fire were socially successful. However, a high social differentiation of primitive social forms of organization cannot be assumed. The first graspable societies as well as similar present groups appear relatively equal (egalitarian). The isolation of individual groups, e.g. during the glacial periods or in insular settlement areas, led to culturally different traditions as well as to phenotypic, also racial theoretical differentiations.[4] The comparatively rare contacts were found by a pedestrian, overall stationary society in the nearest vicinity. Whether the exogamy (external marriage) indicates that people became aware of reproductive biology (procreation) is doubted; exogamy is sociologically seen rather as a proving safeguard of (re-)integration of diverging groupings (for example, in lineage or clan alliances with intermarriage). Some religious traditions also speak of a primal society, referring to the preforms of later religions spread across all hunter-gatherer groupings, derived from the social practices of their members. In written cultures, the distinction between shepherds and cultivators that persists to this day is evident, for example, in the biblical Story of Cain and Abel.[5] Still, in modern macrosociological theories, there are sophisticated assumptions about common features of a primitive society, for instance in Thomas Hobbes, Jean-Jacques Rousseau and Friedrich Engels. Whether early humans lived dominion-free or anarchic or already formed consolidated leadership positions (chiefs) is in each case only a justifiable assumption, the same going for whether they organized themselves as social hordes, cultivated religious cults (with ancestor cult or totemism?) and culturally already knew narrators or familially already the Kernfamilie. Economically, this society is based on an occupation economy, depending on the geological time or vegetation zone to dictate whether one takes the profession of hunter, fisherman, or gatherer.[6] During the Ice Age, for example, their focus in Central Europe and North America was on hunting, while elsewhere gathering and fishing also became important, as in Central Europe after the migration of large animal fauna in the Middle Stone Age (compare Scandinavian middens). In Marxist theory on the social development of mankind, especially in historical materialism, primitive society is also called classless primitive communism[7] because, just as in the "communism" that followed capitalism, there was no private property in the means of production. |

社会は、さまざまな規模の社会集団が共同して形成される。歴史上のさまざまな時代、さまざまな気候や生態系において、人間の社会はまったく異なっていた。 初期のヒト集団の緩やかな拡散(年間1~10キロメートルと推定)は、当初、彼らやその世代継承にほとんど要求を課さなかった。特に赤道付近では、変化を 認識していなかった。しかし、移住者が移住先で直面した氷河期や温暖期といった急激な環境変化により、新たな適応形態とそれに対応する社会構造が生まれ た。 食料収集や天候対策、火の使用は社会的に成功を収めた。しかし、原始的な社会組織の高度な社会分化は想定できない。 初めて把握できる社会や現在の類似グループは、比較的平等(平等主義)である。 氷河期や島嶼部での居住など、個々の集団が孤立したことにより、文化的に異なる伝統が生まれ、表現型や人種理論上の差異も生じた[4]。比較的まれな接触 は、最も近い近隣で、徒歩で移動し、全体的には定住型の社会によって発見された。外婚(外部との結婚)が、人々が生殖生物学(子孫繁栄)に気づいたことを 示すかどうかは疑問視されている。外婚は、むしろ(再)統合の証明となる安全策として社会学的に捉えられている(例えば、血統や氏族の同盟における異種族 間の結婚など)。 一部の宗教的伝統では、原始社会について言及しており、狩猟採集民のグループ全体に広がった後の宗教の初期形態を指し、そのメンバーの社会的慣習に由来し ている。文字文化においては、今日まで続く羊飼いと農耕民の区別は、例えば聖書に登場するカインとアベルの物語[5]に顕著である。それでも、現代のマク ロ社会学理論では、原始社会の共通点について洗練された仮定が立てられている。例えば、トマス・ホッブズ、ジャン=ジャック・ルソー、フリードリヒ・エン ゲルスなどがその例である。 初期の人類が支配のない状態、無政府状態、あるいはすでに首長(chief)による統率された地位を形成していたかどうかは、いずれの場合も正当化できる 仮定にすぎない。彼らが社会的な群れとして組織化していたかどうか、宗教的な崇拝(祖先崇拝やトーテミズムによるもの?)、文化的にすでに語り部を知って いたかどうか、あるいはすでに核家族を形成していたかどうかについても同様である。経済的には、この社会は職業経済に基づいており、地質時代や植生帯に応 じて、狩猟、漁労、採集のどれを職業とするかを決めていた[6]。例えば、氷河期には、中央ヨーロッパや北米では狩猟が中心だったが、他の地域では採集や 漁労も重要になり、中石器時代の大型動物群の移動後の中央ヨーロッパではそうだった(スカンジナビアの貝塚と比較)。 マルクス主義的人類社会発展論、特に歴史的唯物論では、原始社会は階級のない原始共産主義とも呼ばれる[7]。資本主義に続く「共産主義」と同様に、生産手段に私有財産が存在しなかったためである。 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Urgesellschaft |

|

| アッシジのフランチェスコに比べればトマス・アキナスが詩的才能を発揮したとは思われていない.だが後者にはそれに比肩する詩的能力がありその[言語的]修辞は[それとは共存しない]絵画のようであるとチェスタトンはいう 反語の反語的用法 |

|

| It

is often said that St. Thomas. unlike St. Francis, did not permit in

his work the indescribable element of poetry. As, for instance, that

there is little reference to any pleasure in the actual flowers and

fruit of natural things, though any amount of concern with the buried

roots of nature. And yet I confess that, in reading his philosophy, I

have a very peculiar and powerful impression analogous to poetry.

Curiously enough, it is in some ways more analogous to painting, and

reminds me very much of the effect produced by the best of the modern

painters, when they throw a strange and almost crude light upon stark

and rectangular objects, or seem to be groping for rather than grasping

the very pillars of the subconscious mind. It is probably because there

is in his work a quality which is Primitive, in the best sense of a

badly misused word; but any how, the pleasure is definitely not only of

the reason, but also of the imagination. |

聖

トマスは聖フランシスコとは異なり、その著作において詩的な要素を許さなかったと言われる。例えば、自然の根幹にはいくらでも言及しながら、実際の花や実

といった自然の産物そのものの喜びについてはほとんど触れられていない。しかし私は、彼の哲学を読むと、詩に似た非常に独特で強い印象を受けると認めざる

を得ない。奇妙なことに、それはある意味で絵画に近く、現代の優れた画家たちが、無骨で直線的な物体に奇妙でほとんど粗野な光を投げかけたり、無意識の心

の支柱そのものを掴むというよりむしろ探り当てようとしているかのような、その効果を強く思い起こさせるのだ。おそらく彼の作品には、誤用されがちな言葉

の最も良い意味で「原始的=未開的」な性質があるからだろう。いずれにせよ、その愉しみは明らかに理性だけでなく想像力にも訴えかけるのだ。 |

| https://www.ccel.org/ccel/c/chesterton/aquinas/cache/aquinas.pdf | VIII. THE SEQUEL TO ST. THOMAS より |

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆