かならず読んでください

マヤ学入門

Introduction to

Maya Culture and Maya studies

解説:池田光穂

左::メキシコ・チアパス州のシナカンタンの若者(George E. Stuart and National

Geographic);右:ヤ

シュチラン遺跡の石彫(Detail of Lintel 26 from Yaxchilan)

マヤ民族(マヤ人)︎▶︎マヤ遺跡

観光▶︎︎マヤ文化と社会▶︎マヤ先住民表象のダイナミズム(Ver.2.0)2009▶︎︎ポータル:マヤ学入門▶Todos Santeros y Yo︎▶︎︎現代のマヤの人口を推定する▶︎マヤ遺

跡観光▶︎︎▶︎▶︎

「みなさんはマヤ文明について見たり聞いたりしたこ

とがあるでしょう? 映画『スターウォーズ』

(1977)の反乱軍の基地として有名になった熱帯雨林にそびえ立つティカル遺跡のピラミッド、精緻なカレンダーシステム、解明がすすんだマヤ文字な

ど。マヤ文明はエキゾチックな魅力でいっぱいです。しかし他方でグアテマラ高地の先住民族であるマ

ヤ人は、36年にわたる内戦のみならず現在においても虐

殺や政治的抑圧の対象でもあります。この授業では、マヤ民族のうちマム語を話す人びとたちに焦点をあてて、その文化と社会について考えてみたいと思いま

す」(「グアテマラのマヤ文化と社会」より)。

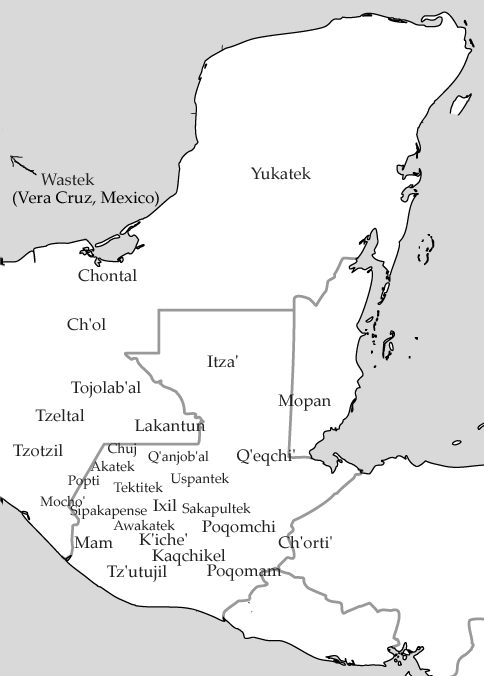

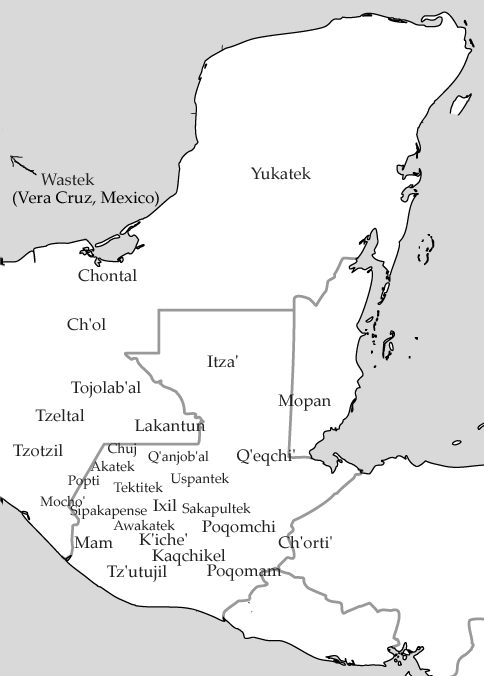

現

代のマヤの人口を推定する;【主張】現在のマヤ民族は、メキシコ南部(チアパス州、ラカンドン低地、ユカタン半島)、ベリーズ、グアテマラ、ホン

ジュラス(西部)ならびにアメリカ合衆国の各地に居住しており、およそ800万から1000万の総人口をもつと推計される。【根拠】世界のマヤ人の総人口

(2004年)を800万から1000万とした推定の根拠は次のとおりである。グアテマラ国内人口の推計(アメリカ合衆国政府公表)1150万人と国外の

労働者推計人口117万人(日刊紙『プレンサ・リブレ紙』2003年9月14日付)の合算の「6割」(根拠は Leopoldo

1997:50)、つまり760万人に、メキシコ国内のマヤ人口94万人――国立先住民研究所による1995年推計統計(INI,

Online)ではマヤという統一カテゴリとそれぞれの各言語別人口が混在しており、それらを合算すると210万人になるがその正確な包摂関係が記されて

いない――を合算したものが854万人(INI統計を単純集計と考えると970万人)である。ただし、このカウントにはメキシコ出身の海外在住のマヤ人が

含まれていない。言うまでもなく、マヤ人の人口統計は当事者の民族的帰属意識によるカウ

ントがもっとも「公正」である。しかし、これまでの歴史的統計は「先住民性」を操作的に規定する研究者の推計に他ならないし、国家統計調査では、非マヤの

調査官による判別や“先住民の文化的特質は将来消失しより大きな国民的範疇に包合されるだろう”という反先住民的偏見や先住民への差別意識により、統計上

の人口規模は過小評価され年次を重ねて減少傾向にあるという「事実」が積み重ねられてきた(Leopoldo

1997)。したがって公表される先住民人口統計にはつねに注意が必要である。Leopoldo, Tzian 1997 Kajlab'aliil

Maya'iib' Xuq Mu'siib': Ri Ub'antajiik Iximuleew ( Mayas y Ladinos en

Cifras: El caso de Guatemala). Guatemala: Cholsamaj.

The Maya

civilization developed within the Maya Region, a Mesoamerican cultural

area, which covers a region that spreads from northern Mexico

southwards into Central America.[3] Mesoamerica was one of six cradles

of civilization worldwide.[4] The Mesoamerican area gave rise to a

series of cultural developments that included complex societies,

agriculture, cities, monumental architecture, writing, and calendrical

systems.[5] The set of traits shared by Mesoamerican cultures also

included astronomical knowledge, blood and human sacrifice, and a

cosmovision that viewed the world as divided into four divisions

aligned with the cardinal directions, each with different attributes,

and a three-way division of the world into the celestial realm, the

earth, and the underworld.[6]

|

マヤ文明は、メキシコ北部から中米にかけてのメソアメリカ文化圏である

マヤ地方で発展した[3]。メソアメリカは、世界6大文明発祥地のひとつである[4]。

[5]メソアメリカ文化が共有する一連の特徴には、天文学的知識、血と人間の犠牲、そして世界を、それぞれ異なる属性を持つ、枢機卿の方位に沿った4つの

部門に分割して見る宇宙観、天界、地上、地下への世界の3方向分割も含まれていました[6]。

|

By 6000 BC, the early

inhabitants of Mesoamerica were experimenting with the domestication of

plants, a process that eventually led to the establishment of sedentary

agricultural societies.[7] The diverse climate allowed for wide

variation in available crops, but all regions of Mesoamerica cultivated

the base crops of maize, beans, and squashes.[8] All Mesoamerican

cultures used Stone Age technology; after c. 1000 AD copper, silver and

gold were worked. Mesoamerica lacked draft animals, did not use the

wheel, and possessed few domesticated animals; the principal means of

transport was on foot or by canoe.[9] Mesoamericans viewed the world as

hostile and governed by unpredictable deities. The ritual Mesoamerican

ballgame was widely played.[10] Mesoamerica is linguistically diverse,

with most languages falling within a small number of language

families—the major families are Mayan, Mixe–Zoquean, Otomanguean, and

Uto-Aztecan; there are also a number of smaller families and isolates.

The Mesoamerican language area shares a number of important features,

including widespread loanwords, and use of a vigesimal number

system.[11]

|

紀元前6000年頃には、メソアメリカの初期住民は植物の家畜化を試み

ており、このプロセスは最終的に定住型農業社会の確立につながった[7]。多様な気候により、収穫できる作物は大きく異なるが、メソアメリカのすべての地

域でトウモロコシ、豆、カボチャという基礎作物が栽培されていた[8]。メソアメリカは徴用動物を持たず、車輪も使わず、家畜化された動物もほとんど持っ

ていませんでした。メソアメリカは言語的に多様で、ほとんどの言語は少数の言語族(マヤ語族、ミックス・ゾクアン語族、オトマンゲ語族、ウト・アステカ語

族)に属しています。メソアメリカ言語圏は、広範な借用語や金数法の使用など、多くの重要な特徴を共有している[11]。

|

The territory of the Maya

covered a third of Mesoamerica,[12] and the Maya were engaged in a

dynamic relationship with neighbouring cultures that included the

Olmecs, Mixtecs, Teotihuacan, the Aztecs, and others.[13] During the

Early Classic period, the Maya cities of Tikal and Kaminaljuyu were key

Maya foci in a network that extended beyond the Maya area into the

highlands of central Mexico.[14] At around the same time, there was a

strong Maya presence at the Tetitla compound of Teotihuacan.[15]

Centuries later, during the 9th century AD, murals at Cacaxtla, another

site in the central Mexican highlands, were painted in a Maya

style.[16] This may have been either an effort to align itself with the

still-powerful Maya area after the collapse of Teotihuacan and ensuing

political fragmentation in the Mexican Highlands,[17] or an attempt to

express a distant Maya origin of the inhabitants.[18] The Maya city of

Chichen Itza and the distant Toltec capital of Tula had an especially

close relationship.[19]

|

マヤの領土はメソアメリカの3分の1を占めており[12]、マヤはオル

メカ、ミクステカ、テオティワカン、アステカなどを含む近隣の文化とダイナミックな関係を築いていた。 [13]

古典前期、マヤの都市ティカルとカミナルジュユは、マヤの領域を超えて中央メキシコの高地にまで広がるネットワークにおけるマヤの重要な拠点でした

[14]。ほぼ同時期に、テオティワカンのテティトラ遺跡にマヤが強く存在していました。 [15]

それから数世紀後の西暦9世紀には、メキシコ中央部の高地にある別の遺跡、カカストラの壁画がマヤの様式で描かれていた。

[16]これは、テオティワカンの崩壊とそれに伴うメキシコ高地の政治的分断の後、依然として強力なマヤ地域と連携するための努力か[17]、あるいは住

民の遠いマヤ起源を表現する試みだったのかもしれない。 18]

マヤ都市チチェン・イッツァと遠いトルテック族の首都トゥーラは特に密接な関係を持っていた[19]。 |

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Maya_civilization

|

|

詳しくは八杉佳穂編『マヤ学を学ぶ人のために』世界

思想社、2004年を読みましょう!

■ 年代区分を知ろう!- List

of archaeological periods (Mesoamerica).

Paleo-Indian

(10,000–3500 BCE)

|

Honduras, Guatemala, Belize, obsidian and pyrite points,

Iztapan

|

(10,000–3500 BCE) |

Archaic

(3500–1800 BCE)

|

Agricultural settlements, Tehuacán

|

(3500–1800 BCE) |

Preclassic (Formative)

(2000 BCE–250 CE)

|

The first large scale ceremonial architecture, development of

cities.

(Olmecs; Unknown culture in La Blanca and Ujuxte, Monte Alto culture)

|

Early Preclassic

|

Olmec area: San Lorenzo

Tenochtitlan; Central Mexico: Chalcatzingo; Valley of Oaxaca: San José

Mogote. The Maya area: Nakbe, Cerros

|

2000–1000 BCE

|

|

|

Middle Preclassic

|

Olmec area: La Venta, Tres

Zapotes; Maya area: El Mirador, Izapa, Lamanai, Xunantunich, Naj

Tunich, Takalik Abaj, Kaminaljuyú, Uaxactun; Valley of Oaxaca: Monte

Albán

|

1000–400 BCE

|

|

|

Late Preclassic

|

Maya area: Uaxactun, Tikal,

Edzná, Cival, San Bartolo, Altar de Sacrificios, Piedras Negras,

Ceibal, Rio Azul; Central Mexico: Teotihuacan; Gulf Coast: Epi-Olmec

culture

|

400 BCE–200 CE

|

Classic

(200–900 CE)

|

Height of the nation-states.

(Classic Maya centers, Teotihuacan, Zapotecs)

|

Early Classic

|

Maya area: Calakmul, Caracol,

Chunchucmil, Copán, Naranjo, Palenque, Quiriguá, Tikal, Uaxactun,

Yaxha; Teotihuacan apogee; Zapotec apogee.

|

200–600 CE

|

|

|

Late Classic

|

Maya area: Uxmal, Toniná, Cobá,

Waka', Pusilhá, Xultún, Dos Pilas, Cancuen, Aguateca; Central Mexico:

Xochicalco, Cacaxtla, Cholula; Gulf Coast: El Tajín and Classic

Veracruz culture

|

600–900 CE

|

|

|

Terminal Classic

|

Maya area: Puuc sites – Uxmal,

Labna, Sayil, Kabah

|

800–900/1000 CE

|

Postclassic

(900–1519 CE)

|

Collapse of many of the great nations and cities of the

Classic Era. Formation of new kingdoms and empires.

(Aztec, Toltec, Purépecha, Mixtec, Totonac, Pipil, Itzá, Kowoj,

K'iche', Kaqchikel, Poqomam, Mam)

|

Early Postclassic

|

Tula, Mitla, Tulum, Topoxte,

Chichen Itza

|

900–1200 CE

|

|

|

Late Postclassic

|

Tenochtitlan, Cempoala,

Tzintzuntzan, Mayapán, Ti'ho, Utatlán, Iximche, Mixco Viejo, Zaculeu

|

1200–1519 CE

|

Post Conquest

(Until 1697 CE)

|

Central Peten: Tayasal, Zacpeten

|

|

|

|

マヤ考古学概要

蛙もまた水のシンボルだったのだろうか?

マヤ考古学概要

The Maya

civilization (/ˈmaɪə/) of the Mesoamerican people is known by its

ancient temples and glyphs. Its Maya script is the most sophisticated

and highly developed writing system in the pre-Columbian Americas. It

is also noted for its art, architecture, mathematics, calendar, and

astronomical system.

|

メソアメリカの人々のマヤ文明(/ˈɪə/)は、その古代寺院とグリフ

(古代文字)で知られています。そのマヤ文字は、コロンブス以前のアメリカ大陸で最も洗練され、高度に発達した文字システムである。また、芸術、建築、数

学、暦、天文システムでも知られています。

|

The Maya civilization developed

in the Maya Region, an area that today comprises southeastern Mexico,

all of Guatemala and Belize, and the western portions of Honduras and

El Salvador. It includes the northern lowlands of the Yucatán Peninsula

and the Guatemalan Highlands of the Sierra Madre, the Mexican state of

Chiapas, southern Guatemala, El Salvador, and the southern lowlands of

the Pacific littoral plain. Today, their descendants, known

collectively as the Maya, number well over 6 million individuals, speak

more than twenty-eight surviving Mayan languages, and reside in nearly

the same area as their ancestors.

|

マヤ文明は、現在のメキシコ南東部、グアテマラ、ベリーズ全域、ホン

ジュラス、エルサルバドルの西部からなるマヤ地方で発展しました。ユカタン半島の北部低地とシエラ・マドレのグアテマラ高地、メキシコのチアパス州、グア

テマラ南部、エルサルバドル、太平洋沿岸平野の南部低地が含まれます。現在、マヤ族と呼ばれる彼らの子孫は600万人を超え、28以上の現存するマヤ語を

話し、祖先とほぼ同じ地域に居住しています。

|

The Archaic period, before 2000

BC, saw the first developments in agriculture and the earliest

villages. The Preclassic period (c. 2000 BC to 250 AD) saw the

establishment of the first complex societies in the Maya region, and

the cultivation of the staple crops of the Maya diet, including maize,

beans, squashes, and chili peppers. The first Maya cities developed

around 750 BC, and by 500 BC these cities possessed monumental

architecture, including large temples with elaborate stucco façades.

Hieroglyphic writing was being used in the Maya region by the 3rd

century BC. In the Late Preclassic a number of large cities developed

in the Petén Basin, and the city of Kaminaljuyu rose to prominence in

the Guatemalan Highlands. Beginning around 250 AD, the Classic period

is largely defined as when the Maya were raising sculpted monuments

with Long Count dates. This period saw the Maya civilization develop

many city-states linked by a complex trade network. In the Maya

Lowlands two great rivals, the cities of Tikal and Calakmul, became

powerful. The Classic period also saw the intrusive intervention of the

central Mexican city of Teotihuacan in Maya dynastic politics. In the

9th century, there was a widespread political collapse in the central

Maya region, resulting in internecine warfare, the abandonment of

cities, and a northward shift of population. The Postclassic period saw

the rise of Chichen Itza in the north, and the expansion of the

aggressive Kʼicheʼ kingdom in the Guatemalan Highlands. In the 16th

century, the Spanish Empire colonised the Mesoamerican region, and a

lengthy series of campaigns saw the fall of Nojpetén, the last Maya

city, in 1697.

|

アルカイック時代(紀元前2000年以前)は、農業の最初の発展や初期

の村落が見られた時代です。前古典期(紀元前2000年頃~紀元後250年頃)には、マヤ地方で最初の複合社会が成立し、トウモロコシ、豆、カボチャ、唐

辛子など、マヤの主食となる作物が栽培されるようになりました。紀元前750年頃、マヤ初の都市が誕生し、紀元前500年頃には、精巧な漆喰のファサード

を持つ大きな神殿など、記念碑的な建築物を持つようになった。紀元前3世紀には、マヤ地方でヒエログリフが使われるようになりました。後期先古典期には、

ペテン盆地に多くの大都市が誕生し、グアテマラ高地ではカミナルジュユという都市が栄えた。紀元250年頃から始まる古典期は、マヤが長い年月を経た彫刻

を施したモニュメントを作る時代と大きく定義されます。この時代、マヤ文明は、複雑な貿易ネットワークで結ばれた多くの都市国家を発展させました。マヤの

低地では、ティカルとカラクムルという2つの都市が強力なライバルとなった。古典期には、メキシコ中央部の都市テオティワカンがマヤ王朝の政治に介入する

ようになった。9世紀には、マヤ中央部の政治が崩壊し、内戦や都市の放棄、人口の北方移動が起こりました。後古典期には、北部のチチェン・イッツァが台頭

し、グアテマラ高地では攻撃的なKʼicheʼ王国が拡大した。16世紀には、スペイン帝国がメソアメリカ地域を植民地化し、長きにわたる一連のキャン

ペーンによって、1697年にマヤ最後の都市であるノホペテンが陥落する。

|

Rule during the Classic period

centred on the concept of the "divine king", who was thought to act as

a mediator between mortals and the supernatural realm. Kingship was

usually (but not exclusively) [1] patrilineal, and power normally

passed to the eldest son. A prospective king was expected to be a

successful war leader as well as a ruler. Closed patronage systems were

the dominant force in Maya politics, although how patronage affected

the political makeup of a kingdom varied from city-state to city-state.

By the Late Classic period, the aristocracy had grown in size, reducing

the previously exclusive power of the king. The Maya developed

sophisticated art forms using both perishable and non-perishable

materials, including wood, jade, obsidian, ceramics, sculpted stone

monuments, stucco, and finely painted murals.

|

古典期の支配は「神王」という概念を中心に行われ、神王は人間と超自然

的な領域の調停者として機能すると考えられていた。王権は通常(ただし、これに限定されない)[1]父系制で、権力は通常、長男に継承されました。王とな

るべき者は、支配者であると同時に戦争指導者としても成功することが期待された。閉鎖的な後援制度はマヤの政治を支配していたが、後援制度が王国の政治構

成にどのような影響を与えるかは都市国家によって異なるものであった。古典後期には、貴族階級が拡大し、それまで独占的だった王の権力が弱まりました。マ

ヤは、木材、ヒスイ、黒曜石、陶器、彫刻された石碑、漆喰、精巧に描かれた壁画など、腐敗しやすい材料と腐敗しにくい材料を用いて洗練された芸術様式を開

発しました。

|

Maya cities tended to expand

organically. The city centers comprised ceremonial and administrative

complexes, surrounded by an irregularly shaped sprawl of residential

districts. Different parts of a city were often linked by causeways.

Architecturally, city buildings included palaces, pyramid-temples,

ceremonial ballcourts, and structures specially aligned for

astronomical observation. The Maya elite were literate, and developed a

complex system of hieroglyphic writing. Theirs was the most advanced

writing system in the pre-Columbian Americas. The Maya recorded their

history and ritual knowledge in screenfold books, of which only three

uncontested examples remain, the rest having been destroyed by the

Spanish. In addition, a great many examples of Maya texts can be found

on stelae and ceramics. The Maya developed a highly complex series of

interlocking ritual calendars, and employed mathematics that included

one of the earliest known instances of the explicit zero in human

history. As a part of their religion, the Maya practised human

sacrifice.

|

マヤの都市は、有機的に拡大する傾向がありました。都市の中心は儀式や

行政のための複合施設で、その周囲には不規則に広がる住宅地が広がっていました。都市の各部分は、しばしば土手道によって結ばれていました。建築的には、

宮殿、ピラミッド神殿、儀式用の球技場、天体観測のために特別に配置された建造物など、さまざまなものがあります。マヤのエリートは文字を読むことがで

き、複雑なヒエログリフのシステムを開発しました。彼らのものは、コロンブス以前のアメリカ大陸で最も高度な文字システムでした。マヤの歴史や儀式に関す

る知識は屏風絵に記録され、そのうちの3冊がスペイン人によって破壊され、現存していないことが確認されています。また、マヤのテキストは、ステラや陶磁

器に数多く残されています。マヤは、非常に複雑な一連の儀式用暦を開発し、人類史上最も早い時期に明示的なゼロを含む数学を使用した。マヤは宗教の一環と

して、人間の生け贄を捧げることを実践していました。

|

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Maya_civilization

|

|

マヤ暦(Maya

calendar)

■ ビデオ解説

ビデオは、ジョン・アンギュー監督『ジャ

ングルの中のマヤ王(The Maya Load

of the Jungle)』でした。

2002年4月30日の授業で解説しまし

たが、このビデオの論理的構成は次のようになっています。思い出しながら、整理して下さい。ま

た、皆さんの関心がどこにあるのか、自分で分析しましょう。

問題:古代マヤの人たちはジャングルの中になぜ巨

大なピラミッドを建てたのか?

与えられた考古学上の条件:

熱帯雨林における農業生産性は低い。

焼畑による2,3年の耕作と、8年程度の

休耕が必要。

焼畑による環境劣悪の資料は出てくるか?

農業生産性の高さが権力と結びつく。

水草の積み上げによる農耕は焼畑よりも生産性が高い。

農業生産性のみが権力の源泉か? 通商交易による権力の調達は?

権力がないと巨大なピラミッドは建てられ

ない。

王権という権力と、それを表象するシンボ

ル(水草/睡蓮と魚)

王権とその表象

ピラミッドの装飾:王個人の顔から神その

ものへの変化

神聖王とはなにか?

(フレイザー『金枝篇(きんしへん)』を

参照のこと[文化人類学年表])

●THE GUATEMALAN MAYA CENTRE

-- 94B Wandsworth Bridge Road, London SW6 2TF : : : : :

curator@maya.org.uk

This outstanding work documents

traditional religious specialists and their practices among Chuj,

Q’anjob’al, and Akatek Mayan speakers residing in the remote fastness

of the high Cuchumatan mountains in northwest Guatemala’s department of

Huehuetenango. Detailed and specific, the book is long on data and

thankfully less concerned with analysis. It is invaluable as a record

of disappearing traditions and equally valuable as information

contributing to understanding the meanings of related traditions placed

in context and explained by followers of those traditions.

グアテマラ北西部ウエウエテナンゴ県にあるクチュマタン山脈の高地に住むチュフ、カンホ

バル、アカテック・マヤの伝統的な宗教専門家とその実践を記録した優れた著作。本書は、詳細かつ具体的で、データに長いが、ありがたいことに分析には

あまり関心がない。本書は、失われつつある伝統の記録として貴重であると同時に、関連する伝統の意味を理解するのに役立つ情報として、その伝統の信奉者が

文脈に即して説明したものであり、同様に価値がある。

Archaeologists and epigraphers will find

careful descriptions of material goods and fascinating practices that

may help identify excavated materials and activities from earlier

times. Ethnohistorians will be pleased to find that Krystyna Deuss

discusses relevant materials provided by earlier ethnographers and has

numerous comments on ritual practices, when some of them originated if

known, and when some practices were no longer present. Art historians

will encounter images and their descriptions that beg comparison with

images from Classic period iconography, as, for example, with the

sacred bundle associated with change of office rituals, or the

placement of altars and crosses as approaches to the supernatural

world, or the staff of office carried by community authorities.

Anthropological linguists too are provided ample material for

identification and analysis, such as an appendix of prayers and

invocations in the original Mayan languages as well as in English

translation, and Deuss supplies much of the necessary context for more

fully apprehending their meaning in the book’s main body. Social

anthropologists will of course also find the data fascinating, given

the book’s painstaking and well-illustrated descriptions of feasts and

festivals, life crisis rituals (including birth, baptism, marriage, and

the Day of the Dead), and rituals for planting, rain, preventing frost

damage, and maintaining and renewing the health of the community.

Descriptions are also given for ritual cleaning of the sacred bundles

and for closing-the-year ceremonies that entail cutting new staffs of

office, cleaning the prayer-sayer’s house, and closing the altars.

考古学者やエピグラファーは、発掘された資料や以前

の活動を特定するのに役立つかもしれない、物質的な品物や魅力的な慣習に関する丁寧な記述を見つけるこ

とができるでしょう。民族史家は、Krystyna

Deussが以前の民族学者によって提供された関連資料を考察し、儀式慣行について、その起源がわかっている場合はその時期、いくつかの慣行がもはや存在

しない場合について多くのコメントを残していることに満足することでしょう。美術史家は、古典期の図像と比較する必要がある画像とその記述に出会う。例え

ば、交代儀式に関連する神聖な束、超自然的な世界へのアプローチとしての祭壇と十字架の配置、コミュニティの権威者が持つ役職の杖などである。人類学的言

語学者にとっても、マヤの原語と英訳による祈りと呼びかけの付録など、識別と分析のための十分な資料が提供され、ドイスは本書の本文でその意味をより深く

理解するために必要な多くの文脈を提供しています。もちろん、社会人類学者にとっても、本書は興味深い資料である。祝祭日や祭事、生命の危機に関する儀式

(誕生、洗礼、結婚、死者の日など)、植樹、雨、凍害防止、コミュニティの健康の維持・更新に関する儀式などが、丹念かつ詳細に図解されているからであ

る。また、神棚の掃除や、新しい杖を切り、祈祷師の家を掃除し、祭壇を閉じるという年末の儀式についても説明されている。

考古学者やエピグラファーは、発掘された資料や以前

の活動を特定するのに役立つかもしれない、物質的な品物や魅力的な慣習に関する丁寧な記述を見つけるこ

とができるでしょう。民族史家は、Krystyna

Deussが以前の民族学者によって提供された関連資料を考察し、儀式慣行について、その起源がわかっている場合はその時期、いくつかの慣行がもはや存在

しない場合について多くのコメントを残していることに満足することでしょう。美術史家は、古典期の図像と比較する必要がある画像とその記述に出会う。例え

ば、交代儀式に関連する神聖な束、超自然的な世界へのアプローチとしての祭壇と十字架の配置、コミュニティの権威者が持つ役職の杖などである。人類学的言

語学者にとっても、マヤの原語と英訳による祈りと呼びかけの付録など、識別と分析のための十分な資料が提供され、ドイスは本書の本文でその意味をより深く

理解するために必要な多くの文脈を提供しています。もちろん、社会人類学者にとっても、本書は興味深い資料である。祝祭日や祭事、生命の危機に関する儀式

(誕生、洗礼、結婚、死者の日など)、植樹、雨、凍害防止、コミュニティの健康の維持・更新に関する儀式などが、丹念かつ詳細に図解されているからであ

る。また、神棚の掃除や、新しい杖を切り、祈祷師の家を掃除し、祭壇を閉じるという年末の儀式についても説明されている。

Based on fieldwork spanning some thirty

years, beginning in 1974, this book is written in the first person, in

a straightforward narrative style, making it both interesting and easy

for the reader to understand. One of its standout points is that it is

exceptionally well illustrated, with fifty drawings (including four

maps) and a hundred photographs, all of them relevant and well chosen.

The drawings are particularly useful for grasping the details of

placement and the positioning of individuals during ritual activities

as well as of the ceremonial paraphernalia used. The communities

selected for description are Santa Eulalia, Chimbán, Soloma, San Juan

Ixcoy, San Sebastián Coatán, and San Mateo Ixtatán.

本書は、1974年から約30年にわたるフィールドワークに基づき、一人称で、わかりや

すい語り口で書かれており、読者にとって興味深く、かつ理解しやすいものとなっている。本書の特筆すべき点は、50枚の図面(うち4枚は地図)と100枚

の写真で構成されている点である。特に図版は、儀式中の配置や個人の位置関係、儀式に使用される道具の詳細を把握するのに有効である。記述のために選ばれ

たコミュニティは、サンタ・エウラリア、チンバン、ソロマ、サン・フアン・イクスコイ、サン・セバスティアン・コタン、サン・マテオ・イスタタンです。

It is a rare bit of good fortune for

Mesoamericanists that Deuss has provided such a detailed report and of

a topic that was not part of her original intent. That intent had not

been to examine the shamans, daykeepers, prayer-makers, and witches of

the region, but rather it had been to collect village costumes to

examine how they evolved during the twentieth century. However, her

original interest in clothing led her to meetings with traditional

religious functionaries in the several communities that she visited,

and these encounters led in turn to her being allowed to witness

rituals no other outsider had ever seen. This opportunity, combined

with the eye of a keen observer and the inquiring vision of an

excellent ethnographer, has given us an invaluable contribution to the

ethnography of this Mayan region, one that will surely endure for its

exemplary description, its methodological insights, and the fascinating

customs and traditions themselves that are so clearly presented.

このような詳細な報告を、しかも当初の目的とは異なるテーマで行ったことは、メソアメリ

カ研究者にとって稀に見る幸運である。その目的は、この地域のシャーマン、デイキーパー、祈祷師、魔女を調べることではなく、村の衣装を集め、20世紀に

それらがどのように進化したかを調べることだったのです。しかし、もともと衣服に興味があった彼女は、訪問したいくつかの集落で伝統的な宗教関係者と会う

ことになり、その結果、他の部外者が見たことのない儀式に立ち会うことを許された。このような機会に、鋭い観察者の目と優れた民俗学者の探究心が加わり、

このマヤ地域の民俗学に貴重な貢献ができたのである。

Doesn’t

seem possible’: Londoner who wants to house Afghan refugees, from

The Gardian. Tue 15 Feb 2022 10.50 GMT

●リンク(サイト内)

文

献

八杉佳穂編『マヤ学を学ぶ人のために』

世界思想社、2004年

Deuss,

Krysyna. Chimban.

in "Shamans,

Witches, and Maya Priests: Native Religion and Ritual in Highland

Guatemala." London: the

Guatemalan Maya Centre. 2013.

Deuss,

Krysyna.Indian

costumes from Guatemala. / Krystyna Deuss. 1990.

Deuss,

Krysyna. Fest der

Farben : Trachten und Textilien aus dem Hochland von Guatemala.

/ Krystyna Deuss ; [übersetzt von Susanne Radlberger-Freude], [s.n.] ,

1981.

︎『暴力の政治民族誌:現代マヤ先住民の経験と記憶

』 池田光穂 著/大阪大学出版会 刊 2020年

そ

の他の情報

Copyleft, CC,

Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

池田蛙 授業蛙 電脳蛙 医人蛙 子供蛙

古代マ

ヤ文明入門

古代マ

ヤ文明入門

++

Copyleft,

CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

考古学者やエピグラファーは、発掘された資料や以前

の活動を特定するのに役立つかもしれない、物質的な品物や魅力的な慣習に関する丁寧な記述を見つけるこ

とができるでしょう。民族史家は、Krystyna

Deussが以前の民族学者によって提供された関連資料を考察し、儀式慣行について、その起源がわかっている場合はその時期、いくつかの慣行がもはや存在

しない場合について多くのコメントを残していることに満足することでしょう。美術史家は、古典期の図像と比較する必要がある画像とその記述に出会う。例え

ば、交代儀式に関連する神聖な束、超自然的な世界へのアプローチとしての祭壇と十字架の配置、コミュニティの権威者が持つ役職の杖などである。人類学的言

語学者にとっても、マヤの原語と英訳による祈りと呼びかけの付録など、識別と分析のための十分な資料が提供され、ドイスは本書の本文でその意味をより深く

理解するために必要な多くの文脈を提供しています。もちろん、社会人類学者にとっても、本書は興味深い資料である。祝祭日や祭事、生命の危機に関する儀式

(誕生、洗礼、結婚、死者の日など)、植樹、雨、凍害防止、コミュニティの健康の維持・更新に関する儀式などが、丹念かつ詳細に図解されているからであ

る。また、神棚の掃除や、新しい杖を切り、祈祷師の家を掃除し、祭壇を閉じるという年末の儀式についても説明されている。

考古学者やエピグラファーは、発掘された資料や以前

の活動を特定するのに役立つかもしれない、物質的な品物や魅力的な慣習に関する丁寧な記述を見つけるこ

とができるでしょう。民族史家は、Krystyna

Deussが以前の民族学者によって提供された関連資料を考察し、儀式慣行について、その起源がわかっている場合はその時期、いくつかの慣行がもはや存在

しない場合について多くのコメントを残していることに満足することでしょう。美術史家は、古典期の図像と比較する必要がある画像とその記述に出会う。例え

ば、交代儀式に関連する神聖な束、超自然的な世界へのアプローチとしての祭壇と十字架の配置、コミュニティの権威者が持つ役職の杖などである。人類学的言

語学者にとっても、マヤの原語と英訳による祈りと呼びかけの付録など、識別と分析のための十分な資料が提供され、ドイスは本書の本文でその意味をより深く

理解するために必要な多くの文脈を提供しています。もちろん、社会人類学者にとっても、本書は興味深い資料である。祝祭日や祭事、生命の危機に関する儀式

(誕生、洗礼、結婚、死者の日など)、植樹、雨、凍害防止、コミュニティの健康の維持・更新に関する儀式などが、丹念かつ詳細に図解されているからであ

る。また、神棚の掃除や、新しい杖を切り、祈祷師の家を掃除し、祭壇を閉じるという年末の儀式についても説明されている。