Action Research and Action Anthropology

アクションリサーチ

Action Research and Action Anthropology

アクション・リサーチ(action resarch)あ

るいは唱道的アプローチ(advocacy

approach)はプロジェクトを施行する側と住民(行政モデルではしばしばクライアントや受益者・ステイクホルダーと呼ばれた)を明確

に区別せず、住民の主体的な発展を促すため

に人類学者がプロジェクトに参画しながら調査を行なうというスタイルのことをさす(→出典:「関

与=介入する」)。

北アメリカ大陸では、すでに 20年以上のあいだに地歩を築きつつあるアプローチで、その歴史的ルーツは半世紀以上にさかのぼれる。

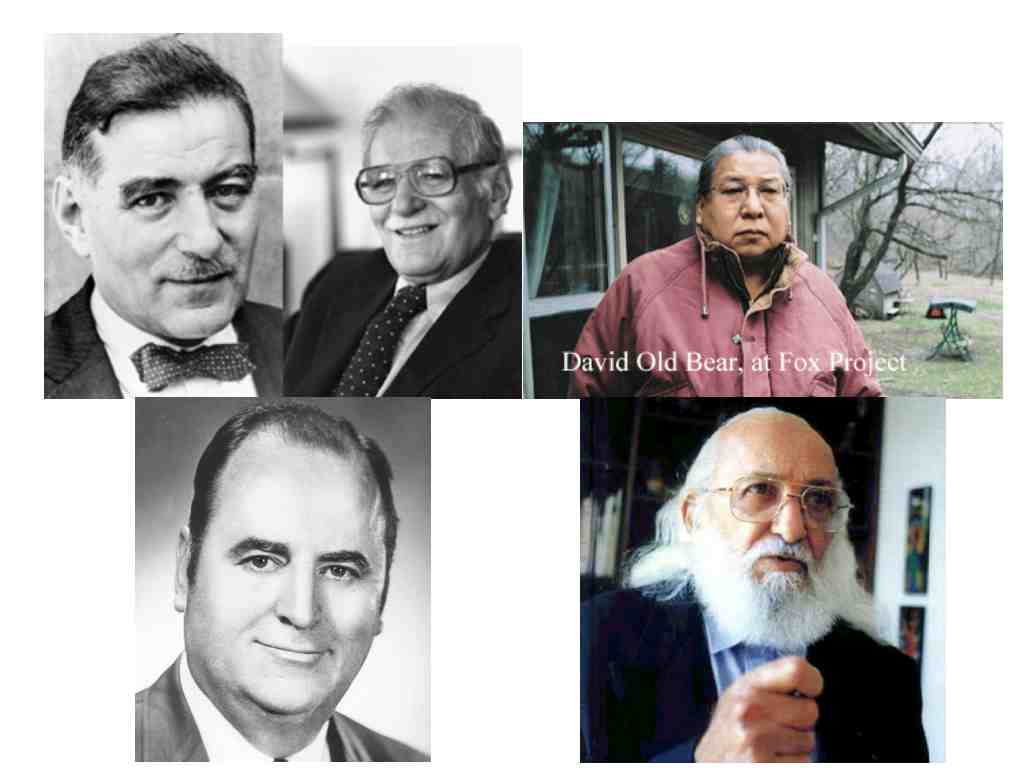

ク ルト・レヴィン(Kurt Lewin, 1890-1947)はアクション・リサーチという用 語を1944-46年ごろに提唱し、社会的実践(social action)を引き出すための、アクション(行為)と研究の螺旋的運動形態として位置づけ、社会心理学上の理論をもちいて説明した。[→協働術A:アクションリサーチの理論と実践]

また文化人類学者ソ ル・タックス(Sol Tax, 1907-1995)は、1938年から62年まで、アイオワ州Tama において、先住民フォックス(メスクァキィ Mesquakie)インディアンの調査研究をおこなうのみならず、それが先住民の生活にどのように役立つのかについて、住民と調査研究に関わる学生との 交渉のなかで決定してゆくという研究手法を開発した。それは今日ではアクション人類学(action anthropology)と呼ばれている。

またパウロ・フレイレ(Paulo Freire, 1921-1997)はブラジルを中心にしてラテンアメリカの成人教育、とくに識字教育の経験(『抑圧された人たちの教育学』)からいわゆる批判的教育学 の立場を打ち出し、実践を生み出す自由の概念とそれを疎外する抑圧、知識を断片的に生徒に与えてゆく銀行型教育を批判し、意識化を通して、人間の相互了解 にもとづく対話にもとづく学習行動の重要性について力説した(→「制度的民族誌: Institutional Ethnography」)。

コミュニティにもとづく参加型研究は、参加型というところに特徴をもつのであ り、参加型(participatory)抜きのコミュニティの要望を反映させる[→コミュニティにもとづく研究(サイエンスショップ)]、ないしはコミュニティにおいて調査研究するというフィールドワークとは、その方法論や内部者の行動において趣旨を異にする。

現在では「デザイン人類学」の嚆矢のように扱われるが、これはアクションリサーチの精

神性をより、現代的な意味において呼び起こすために重要な取り込みであると、わたし(池田)は確信するものです。

アクションリサーチの表記には、このよう に続けて記載する方法と元の英単語(action resarch) のようにわけてアクション・リサーチとする2つの表記があります。

|

|

アクション・リサーチに 関与する /した人たち出典:コミュニティに基礎をおく参加型研究(CBPR)とは何か?

★参加型アクションリサーチ(Participatory action research, PAR)

参加型行動研究=参加型アクションリサーチ(PAR)

とは、研究対象となるコミュニティの成員によ

る参加と行動を重視する行動研究の手法である。協働と省察を経て世界を変えようとする過程で、世界を理解しようとする。PARは経験と社会史に根ざした集

団的な探究と実験を重視する。PARの過程では、「探究と行動の共同体が形成され、共同研究者として参加する者にとって重要な問題や課題に取り組む」ので

ある。[1] PARは、制御された実験行動、統計分析、結果の再現性を重視する主流の研究手法とは対照的である。

PAR実践者は、自らの活動の三つの基本側面——参加(社会生活と民主主義)、行動(経験と歴史への関与)、研究(思考の妥当性と知識の成長)——を統合

する努力を集中的に行う。[2] 「行動は研究と有機的に結びつき」、集団的な自己探求のプロセスを形成する。[3]

ただし、各構成要素の実際の理解や相対的な重視度は、PARの理論と実践によって異なる。これはPARが一元的な思想や方法論の集合体ではなく、むしろ知

識創造と社会変革に向けた多元的な方向性であることを意味する。[4][5][6]

☆Action research in Wiki

| Action research

is a philosophy and methodology of research generally applied in the

social sciences. It seeks transformative change through the

simultaneous process of taking action and doing research, which are

linked together by critical reflection. Kurt Lewin, then a professor at

MIT, first coined the term "action research" in 1944. In his 1946 paper

"Action Research and Minority Problems" he described action research as

"a comparative research on the conditions and effects of various forms

of social action and research leading to social action" that uses "a

spiral of steps, each of which is composed of a circle of planning,

action and fact-finding about the result of the action". |

アクション・リサーチとは、一般的に社会科学に応用されている研究の哲

学と方法論である。アクション・リサーチとは、アクションを起こすこととリサーチを行うことの同時プロセスを通じて、変革的な変化をもたらすことを目指す

もので、クリティカル・リフレクション(批判的省察)によって結びつけられる。1944年、当時マサチューセッツ工科大学(MIT)の教授であったカー

ト・ルウィンが、初めて「アクション・リサーチ」という言葉を生み出した。彼は1946年の論文「アクション・リサーチとマイノリティ問題」の中で、アク

ション・リサーチとは「さまざまな形態の社会的行動の条件と効果に関する比較研究、および社会的行動につながる研究」であり、「計画、行動、行動の結果に

関する事実発見の輪からなる、それぞれのステップのスパイラル」であると述べている。 |

| Process Action research is an interactive inquiry process that balances problem-solving actions implemented in a collaborative context with data-driven collaborative analysis or research to understand underlying causes enabling future predictions about personal and organizational change.[1][2][3][4][5][6][7][8] After seven decades of action research development, many methods have evolved that adjust the balance to focus more on the actions taken or more on the research that results from the reflective understanding of the actions. This tension exists between: 1. those who are more driven either by the researcher's agenda or by participants; 2. those who are motivated primarily by instrumental goal attainment or by the aim of personal, organizational or 3. societal transformation; and 3. 1st-, to 2nd-, to 3rd-person research, that is, my research on my own action, aimed primarily at personal change; our research on our group (family/team), aimed primarily at improving the group; and 'scholarly' research aimed primarily at theoretical generalization or large-scale change.[9] Action research challenges traditional social science by moving beyond reflective knowledge created by outside experts sampling variables, to an active moment-to-moment theorizing, data collecting and inquiry occurring in the midst of emergent structure. "Knowledge is always gained through action and for action. From this starting point, to question the validity of social knowledge is to question, not how to develop a reflective science about action, but how to develop genuinely well-informed action – how to conduct an action science".[10] In this sense, engaging in action research is a form of problem-based investigation by practitioners into their practice, thus it is an empirical process. The goal is both to create and share knowledge in the social sciences. |

プロセス アクション・リサーチとは、人格や組織の変化に関する将来の予測を可能にする根本的な原因を理解するために、データ駆動型の共同分析または調査と、共同的 な文脈で実施される問題解決行動のバランスをとる対話型の探究プロセスである[1][2][3][4][5][6][7][8]。 アクション・リサーチが70年間発展してきた後、多くの手法が進化し、行動をより重視するか、行動の反省的理解から生まれる研究をより重視するかのバラン スを調整するようになった。この緊張関係は、以下の間に存在する: 1.研究者のアジェンダか参加者のどちらかによって、より推進される; 2. 主に道具的な目標達成や、人格、組織、社会の変革が動機となる者。 3. 1人称研究、2人称研究、3人称研究、つまり、主に個人的な変 化を目的とした自分自身の行動に関する自分自身の研究、主にグル ープを改善することを目的としたグループ(家族/チーム)に関する 我々の研究、主に理論的一般化や大規模な変化を目的とした 「学術的」研究である[9]。 アクション・リサーチは、外部の専門家が変数をサンプリングすることによって作り出される反射的な知識を超えて、創発的な構造のただ中で起こる能動的な瞬 間瞬間の理論化、データ収集、探究へと移行することによって、伝統的な社会科学に挑戦している。「知識は常に行動を通じて、行動のために得られる。この出 発点から、社会的知識の妥当性を問うことは、行動に関する反省的科学を発展させる方法ではなく、真に十分な情報を得た行動を発展させる方法、つまり行動科 学を実施する方法を問うことである」[10]。この意味で、アクション・リサーチに取り組むことは、実践者による実践に対する問題に基づく調査の一形態で あり、したがってそれは経験的なプロセスである。その目的は、社会科学における知識を創造し、共有することである。 |

| Major theoretical approaches Chris Argyris' action science Chris Argyris' action science begins with the study of how human beings design their actions in difficult situations. Humans design their actions to achieve intended consequences and are governed by a set of environment variables. How those governing variables are treated in designing actions are the key differences between single-loop and double-loop learning. When actions are designed to achieve the intended consequences and to suppress conflict about the governing variables, a single-loop learning cycle usually ensues. On the other hand, when actions are taken not only to achieve the intended consequences, but also to openly inquire about conflict and to possibly transform the governing variables, both single- and double-loop learning cycles usually ensue. (Argyris applies single- and double-loop learning concepts not only to personal behaviors but also to organizational behaviors in his models.) This is different from experimental research in which environmental variables are controlled and researchers try to find out cause and effect in an isolated environment. |

主な理論的アプローチ クリス・アーガリスの行動科学 クリス・アーガリスの行動科学は、人間が困難な状況下でどのように行動をデザインするかという研究から始まる。人間は意図した結果を達成するために行動を 設計し、一連の環境変数に支配される。それらの支配変数が行動を設計する際にどのように扱われるかが、シングルループ学習とダブルループ学習の重要な相違 点である。意図した結果を達成し、支配変数に関する葛藤を抑制するように行動が設計される場合、通常、シングルループ学習サイクルが生じる。 一方、意図した結果を達成するためだけでなく、対立について率直に尋ねたり、支配変数を変化させたりするために行動を起こす場合は、通常、シングルループ とダブルループの両方の学習サイクルが発生する。(アーガリスは、シングルループとダブルループの学習概念を、人格行動だけでなく組織行動にも適用してい る)。これは、環境変数が制御され、研究者が孤立した環境で原因と結果を突き止めようとする実験的研究とは異なる。 |

| John Heron and Peter Reason's

cooperative inquiry Main article: Cooperative inquiry Cooperative, aka collaborative, inquiry was first proposed by John Heron in 1971 and later expanded with Peter Reason and Demi Brown. The major idea is to "research 'with' rather than 'on' people." It emphasizes the full involvement in research decisions of all active participants as co-researchers. Cooperative inquiry creates a research cycle among 4 different types of knowledge: propositional (as in contemporary science), practical (the knowledge that comes with actually doing what you propose), experiential (the real-time feedback we get about our interaction with the larger world) and presentational (the artistic rehearsal process through which we craft new practices). At every cycle, the research process includes these four stages, with deepening experience and knowledge of the initial proposition, or of new propositions. |

ジョン・ヘロンとピーター・リーズンの共同調査 主な記事 協同探究 協同的探究は、1971年にジョン・ヘロンによって提唱され、後にピーター・リーズンとデミ・ブラウンによって拡大された。その主要な考え方は、「人々に ついて」研究するのではなく「人々とともに」研究することである。これは、積極的な参加者全員が共同研究者として研究の決定に完全に関与することを強調し ている。 協同探究は、4つの異なるタイプの知識、すなわち命題的知識(現代科学のように)、実践的知識(提案したことを実際にやってみることで得られる知識)、経 験的知識(より大きな世界との相互作用について得られるリアルタイムのフィードバック)、発表的知識(新しい実践を作り上げる芸術的リハーサルプロセス) の間で研究サイクルを生み出す。どのサイクルにおいても、研究プロセスにはこれら4つの段階が含まれ、最初の提案、あるいは新たな提案に対する経験や知識 を深めていく。 |

| Paulo Freire's participatory

action research Main article: Participatory action research Participatory action research builds on the critical pedagogy put forward by Paulo Freire as a response to the traditional formal models of education where the "teacher" stands at the front and "imparts" information to the "students" who are passive recipients. This was further developed in "adult education" models throughout Latin America. Orlando Fals-Borda (1925–2008), Colombian sociologist and political activist, was one of the principal promoters of participatory action research (IAP in Spanish) in Latin America. He published a "double history of the coast", book that compares the official "history" and the non-official "story" of the north coast of Colombia. |

パウロ・フレイレの参加型アクションリサーチ 主な記事 参加型アクションリサーチ 参加型アクション・リサーチは、パウロ・フレイレが提唱した批判的教育学に基づくもので、「教師」が前面に立ち、受動的な受け手である「生徒」に情報を 「与える」という伝統的な形式的教育モデルへの対応として提唱された。これはラテンアメリカ全土の「成人教育」モデルでさらに発展した。 コロンビアの社会学者で政治活動家のオルランド・ファルス=ボルダ(1925-2008)は、ラテンアメリカにおける参加型アクション・リサーチ(スペイ ン語でIAP)の主要な推進者の一人であった。彼は、コロンビア北海岸の公式な「歴史」と非公式な「物語」を比較した「海岸の二重の歴史」を出版した。 |

| William Barry's living

educational theory approach to action research William Barry[11] defined an approach to action research which focuses on creating ontological weight.[12] He adapted the idea of ontological weight to action research from existential Christian philosopher Gabriel Marcel.[13] Barry was influenced by Jean McNiff's and Jack Whitehead's[14] phraseology of living theory action research but was diametrically opposed to the validation process advocated by Whitehead which demanded video "evidence" of "energy flowing values" and his atheistic ontological position which influenced his conception of values in action research.[15] Barry explained that living educational theory (LET) is "a critical and transformational approach to action research. It confronts the researcher to challenge the status quo of their educational practice and to answer the question, 'How can I improve what I'm doing?' Researchers who use this approach must be willing to recognize and assume responsibility for being 'living contradictions' in their professional practice – thinking one way and acting in another. The mission of the LET action researcher is to overcome workplace norms and self-behavior which contradict the researcher's values and beliefs. The vision of the LET researcher is to make an original contribution to knowledge through generating an educational theory proven to improve the learning of people within a social learning space. The standard of judgment for theory validity is evidence of workplace reform, transformational growth of the researcher, and improved learning by the people researcher claimed to have influenced...".[16] |

ウィリアム・バリーの生きた教育理論によるアクションリサーチへのアプ

ローチ ウィリアム・バリー[11]は存在論的な重みを創造することに焦点を当てたアクションリサーチのアプローチを定義した[12]。彼は存在論的な重みの考え 方を実存的なキリスト教哲学者であるガブリエル・マルセルからアクションリサーチに適応させた[13]。バリーはジーン・マクニフとジャック・ホワイト ヘッド[14]のリビングセオリーアクションリサーチのフレーズに影響を受けていたが、「エネルギーが流れる価値観」のビデオによる「証拠」を要求するホ ワイトヘッドが提唱した検証プロセスや、アクションリサーチにおける価値観の概念に影響を与えた彼の無神論的な存在論的立場に正反対であった[15]。 バリーは、生きた教育理論(LET)とは「アクションリサーチに対する批判的で変容的なアプローチ」であると説明している。LETは、教育実践の現状に挑 戦し、『どうすれば自分のやっていることを改善できるか』という問いに答えることを研究者に突きつける。このアプローチを用いる研究者は、自分の専門的実 践において「生きている矛盾」であることを認識し、責任を負わなければならない。LET行動研究者の使命は、研究者の価値観や信念と矛盾する職場の規範や 自己行動を克服することである。LET研究者のビジョンは、社会的学習空間の中で、人々の学習を改善することが証明された教育理論を生み出すことを通じ て、知識に対して独創的な貢献をすることである。理論の妥当性の判断基準は、職場改革、研究者の変容的成長、研究者が影響を与えたと主張する人々による学 習の改善の証拠である」[16]。 |

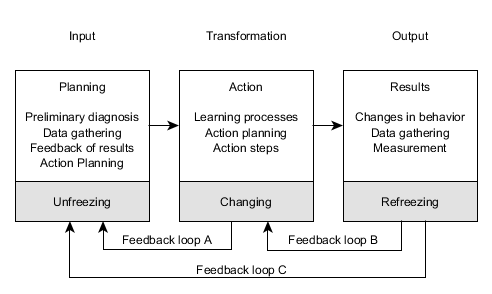

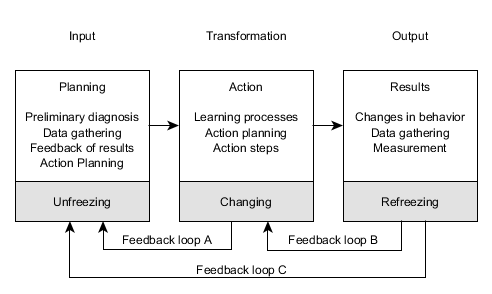

| Action research in organization

development Wendell L. French and Cecil Bell define organization development (OD) at one point as "organization improvement through action research".[17] If one idea can be said to summarize OD's underlying philosophy, it would be action research as it was conceptualized by Kurt Lewin and later elaborated and expanded on by other behavioral scientists. Concerned with social change and, more particularly, with effective, permanent social change, Lewin believed that the motivation to change was strongly related to action: If people are active in decisions affecting them, they are more likely to adopt new ways. "Rational social management", he said, "proceeds in a spiral of steps, each of which is composed of a circle of planning, action and fact-finding about the result of action".[18] - Unfreezing: first step. - Changing: The situation is diagnosed and new models of behavior are explored and tested. - Refreezing: Application of new behavior is evaluated, and if reinforcing, adopted.  Figure 1: Systems model of action-research process Lewin's description of the process of change involves three steps:[18] Figure 1 summarizes the steps and processes involved in planned change through action research. Action research is depicted as a cyclical process of change. 1. The cycle begins with a series of planning actions initiated by the client and the change agent working together. The principal elements of this stage include a preliminary diagnosis, data gathering, feedback of results, and joint action planning. In the language of systems theory, this is the input phase, in which the client system becomes aware of problems as yet unidentified, realizes it may need outside help to effect changes, and shares with the consultant the process of problem diagnosis. 2. The second stage of action research is the action, or transformation, phase. This stage includes actions relating to learning processes (perhaps in the form of role analysis) and to planning and executing behavioral changes in the client organization. As shown in Figure 1, feedback at this stage would move via Feedback Loop A and would have the effect of altering previous planning to bring the learning activities of the client system into better alignment with change objectives. Included in this stage is action-planning activity carried out jointly by the consultant and members of the client system. Following the workshop or learning sessions, these action steps are carried out on the job as part of the transformation stage.[19] 3. The third stage of action research is the output or results phase. This stage includes actual changes in behavior (if any) resulting from corrective action steps taken following the second stage. Data are again gathered from the client system so that progress can be determined and necessary adjustments in learning activities can be made. Minor adjustments of this nature can be made in learning activities via Feedback Loop B (see Figure 1). Major adjustments and reevaluations would return the OD project to the first or planning stage for basic changes in the program. The action-research model shown in Figure 1 closely follows Lewin's repetitive cycle of planning, action, and measuring results. It also illustrates other aspects of Lewin's general model of change. As indicated in the diagram, the planning stage is a period of unfreezing, or problem awareness.[18] The action stage is a period of changing, that is, trying out new forms of behavior in an effort to understand and cope with the system's problems. (There is inevitable overlap between the stages, since the boundaries are not clear-cut and cannot be in a continuous process). The results stage is a period of refreezing, in which new behaviors are tried out on the job and, if successful and reinforcing, become a part of the system's repertoire of problem-solving behavior. Action research is problem centered, client centered, and action oriented. It involves the client system in a diagnostic, active-learning, problem-finding and problem-solving process. |

組織開発におけるアクション・リサーチ ウェンデル・L・フレンチとセシル・ベルは、ある時点で組織開発(OD)を「アクション・リサーチによる組織改善」と定義している[17]。ODの根底に ある哲学を要約する考え方があるとすれば、それはクルト・ルーインによって概念化され、後に他の行動科学者によって精緻化され、拡張されたアクション・リ サーチであろう。社会変化、特に効果的で永続的な社会変化に関心を寄せていたルウィンは、変化への動機づけは行動と強く関連していると考えた: 人民が自分たちに影響を与える決定に積極的に参加すれば、新しい方法を採用する可能性が高くなる。「合理的な社会経営」は、「計画、行動、行動の結果につ いての事実確認の輪からなる各ステップの螺旋状に進行する」と彼は言った[18]。 - 凍結解除:最初のステップ。 - 変化する: 状況が診断され、新しい行動モデルが探求され、テストされる。 - 再凍結: 新しい行動の適用が評価され、強化されれば採用される。  図1:行動研究プロセスのシステムモデル 図 1 は、アクションリサーチを通じて計画された変化に関与するステップとプロセスをまとめたものである。アクション・リサーチは、循環的な変化のプロセスとし て描かれている。 1. このサイクルは、クライアントとチェンジ・エージェントが協力して開始する一連の計画行動から始まる。この段階の主な要素には、予備診断、データ収集、結 果のフィードバック、共同行動計画が含まれる。システム理論の用語で言えば、これはインプット・フェーズであり、クライアント・システムは、まだ特定され ていない問題に気づき、変化をもたらすためには外部の助けが必要かもしれないと気づき、コンサルタントと問題診断のプロセスを共有する。 2. アクション・リサーチの第2段階は、アクション、すなわち変革の段階である。この段階には、学習プロセス(おそらく役割分析の形で)や、クライアント組織 における行動変容の計画と実行に関する行動が含まれる。図1に示すように、この段階でのフィードバックは、フィードバックループAを経由して移動し、以前 の計画を変更して、クライアントシステムの学習活動を変革目標によりよく一致させる効果を持つことになる。この段階に含まれるのは、コンサルタントとクラ イアント・システムのメンバーが共同で実施するアクション・プランニング活動である。ワークショップや学習セッションの後、これらのアクションステップ は、変革ステージの一部として、職務の中で実行される[19]。 3. アクションリサーチの第3段階は、アウトプットまたは結果の段階である。この段階には、第2段階に続いて実施された是正行動ステップの結果生じる、実際の 行動の変化(もしあれば)が含まれる。進捗状況を判断し、学習活動に必要な調整を行うことができるように、クライアントシステムから再びデータが収集され る。このような性質の軽微な調整は、フィードバックループB(図1参照)を通じて学習活動で行うことができる。 大きな調整と再評価は、ODプロジェクトをプログラムの基本的な変更のための最初の段階または計画段階に戻すことになる。図1に示すアクション・リサー チ・モデルは、計画、行動、結果の測定というルヴァンの反復サイクルに忠実に従っている。また、ルウィンの一般的な変化モデルの他の側面も示している。こ の図に示されているように、計画段階は凍結解除、すなわち問題認識の期間である[18] 。行動段階は変化の期間であり、すなわちシステムの問題を理解し、それに対処するために、新しい形の行動を試す期間である。(その境界は明確ではなく、連 続的なプロセスではありえないため、段階間の重複は避けられない)。 結果段階は再凍結の期間であり、そこでは新しい行動が仕事で試され、成功し強化されれば、問題解決行動のシステムのレパートリーの一部となる。アクショ ン・リサーチは、問題中心、クライアント中心、行動指向である。診断、能動的学習、問題発見、問題解決のプロセスにクライアント・システムが関与する。 |

| Worldwide expansion Action research has become a significant methodology for intervention, development and change within groups and communities. It is promoted and implemented by many international development agencies and university programs, as well as local community organizations around the world, such as AERA and Claremont Lincoln in America,[20][21] CARN in the United Kingdom,[22] CCAR in Sweden,[23] CLAYSS in Argentina,[24] CARPED and PRIA in India,[25][26] and ARNA in the Americas.[27] The Center for Collaborative Action Research makes available a set of twelve tutorials as a self-paced online course in learning how to do action research. It includes a free workbook that can be used online or printed. |

世界的な広がり アクション・リサーチは、グループやコミュニティにおける介入、開発、変革のための重要な方法論となっている。アメリカのAERAやクレアモント・リン カーン、[20][21]イギリスのCARN、[22]スウェーデンのCCAR、[23]アルゼンチンのCLAYSS、[24]インドのCARPEDや PRIA、[25][26]アメリカ大陸のARNAなど、世界中の多くの国際的な開発機関や大学プログラム、地域コミュニティ組織によって推進・実施され ている[27]。 Center for Collaborative Action Researchは、アクション・リサーチの方法を学ぶ自習型のオンライン・コースとして、12のチュートリアルを提供している。オンラインでも印刷でも 使える無料のワークブックも含まれている。 |

| Journal The field is supported by a quarterly peer-reviewed academic journal, Action Research, founded in 2003 and edited by Hilary Bradbury.[28] |

ジャーナル この分野は、ヒラリー・ブラッドベリが編集し、2003年に創刊された季刊の査読付き学術誌『アクション・リサーチ』によって支えられている[28]。 |

| Action learning Action teaching Appreciative inquiry Design research Learning cycle Lesson study Praxis intervention Reflective practice |

アクション・ラーニング アクション・ティーチング アプレシエイティブ・インクワイアリー デザインリサーチ 学習サイクル 授業研究 プラクシス介入 リフレクティブ・プラクティス |

| Bibliography General sources Atkins, L & Wallace, S. (2012). Qualitative Research in Education. London: Sage Publications. Burns, D. 2007. Systemic Action Research: A strategy for whole system change. Bristol: Policy Press. Burns, D. 2015. Navigating complexity in international development: Facilitating sustainable change at scale. Rugby: Practical Action Davison, R., Martinsons, M., & Kock, N. (2004). Information Systems Journal, 14(1), 65–86. Greenwood, D. J. & Levin, M., Introduction to action research: social research for social change, Thousand Oaks, California: Sage Publications, 1998. Greenwood, D. J. & Levin, M., Introduction to action research. Second edition, Thousand Oaks, Calif.: Sage Publications, 2007. Martyn Hammersley, "Action research: a contradiction in terms?", Oxford Review of Education, 30, 2, 165–181, 2004. James, E. Alana; Milenkiewicz, Margaret T.; Bucknam, Alan. Participatory Action Research for Educational Leadership: Using Data-Driven Decision Making to Improve Schools. Thousand Oaks: Sage, 2007. ISBN 978-1-4129-3777-1 Noffke, S. & Somekh, B. (Ed.) (2009) The SAGE Handbook of Educational Action Research. London: SAGE. ISBN 978-1-4129-4708-4. Pine, Gerald J. (2008). Teacher Action Research: Building Knowledge Democracies, Sage Publications. Reason, P. & Bradbury, H., (Ed.) The SAGE Handbook of Action Research. Participative Inquiry and Practice. 1st Edition. London: Sage, 2001. ISBN 0-7619-6645-5. (2nd Edition, 2007. ISBN 978-1-4129-2029-2) Rowell, L., Bruce, C., Shosh, J. M., & Riel, M. (2017). The Palgrave international handbook of action research. New York, NY: Palgrave Macmillan. Sherman & Torbert, Transforming Social Inquiry, Transforming Social Action: New paradigms for crossing the theory/practice divide in universities and communities. Boston, Kluwer, 2000. Silverman, Robert Mark, Henry L. Taylor Jr. and Christopher G. Crawford. 2008. "The Role of Citizen Participation and Action Research Principles in Main Street Revitalization: An Analysis of a Local Planning Project", Action Research 6(1): 69–93. Sagor, R. (2010). Collaborative Action Research for Professional. Learning Communities. Bloomington: Solution Tree Press. Stringer, E.T. And Ortiz, A. (2021). Action Research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications. Wood, L., Zuber-Skerritt, O. (2013). "PALAR as a methodology for community engagement by faculties of education". South African Journal of Education, 33, 1–15. Wood, L. (2017) "Community development in higher education: how do academics ensure their community-based research makes a difference?" Community Development Journal, Volume 52, Issue 4, Pages 685–701, https://doi.org/10.1093/cdj/bsv068 Zuber-Skerritt, O., & Wood, L. (2019). Action Learning and Action Research: Genres and Approaches. Emerald (UK). Woodman & Pasmore. Research in Organizational Change & Development series. Greenwich CT: Jai Press. Exemplars and methodological discussions Argyris, C. 1970. Intervention Theory and Method. Reading, Massachusetts: Addison-Wesley. Argyris, C. 1980. Inner Contradictions of Rigorous Research. San Diego, California: Academic Press. Argyris, C. 1994. Knowledge for Action. San Francisco, California: Jossey-Bass. Cameron, K. & Quinn, R. 1999. Diagnosing and Changing Organizational Culture. Reading, Massachusetts: Addison-Wesley. Center for Collaborative Action Research. 2022. Action Research Tutorials. https://www.ccarweb.org/ Denscombe M. 2010. Good Research Guide: For small-scale social research projects (4th Edition). Open University Press. Berkshire, GBR. ISBN 978-0-3352-4138-5 Dickens, L., Watkins, K. 1999. "Management Learning, Action Research: Rethinking Lewin". Vol. 30, Issue 2, pp. 127–140. <https://doi.org/10.1177/1350507699302002> Freire, P. 1970. Pedagogy of the Oppressed''. New York: Herder & Herder. Garreau, J. 2005. Radical Evolution: The promise and peril of enhancing our minds, our bodies – and what it means to be human. New York: Doubleday. Heikkinen, H., Kakkori, L. & Huttunen, R. 2001. "This is my truth, tell me yours: some aspects of action research quality in the light of truth theories". Educational Action Research 1/2001. Heron, J. 1996. Cooperative Inquiry: Research into the human condition. London: Sage. Kemmis, Stephen and McTaggart Robin (1982) The action research planner. Geelong: Deakin University. Kemmis, Stephen, McTaggart, Robin and Nixon, Rhonda (2014) The action research planner. Doing critical participatory action research. Springer. McNiff, J. & Whitehead, J. (2006) All You Need To Know About Action Research, London; Sage. Ogilvy, J. 2000. Creating Better Futures: Scenario planning as a tool for a better tomorrow. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Reason, P. & Rowan, J. 1981. Human Inquiry: A Sourcebook of New Paradigm Research. London: Wiley. Reason, P. 1995. Participation in Human Inquiry. London: Sage. Schein, E. 1999. Process Consultation Revisited. Reading, Massachusetts: Addison-Wesley. Senge, P., Scharmer, C., Jaworski, J., & Flowers, B. 2004. Presence: Human purpose and the field of the future. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Society for Organizational Learning. Susman G.I. and Evered R.D., 1978. "Administrative Science Quarterly, An Assessment of the Scientific Merits of Action Research". Vol. 23, No. 4, pp. 582–603 JSTOR 2392581 Torbert, W. & Associates 2004. Action Inquiry: The Secret of Timely and Transforming Leadership. First-person research/practice exemplars Bateson, M. 1984. With a Daughter's Eye: A Memoir of Margaret Mead and Gregory Bateson. New York: Plume/Penguin. Cuomo, N. (1982). Handicaps 'gravi' a scuola - interroghiamo l'esperienza. Bologna: Nuova Casa Editrice L. Capelli. Cuomo, N. (2007). Verso una scuola dell'emozione di conoscere. Il futuro insegnante, insegnante del futuro. Pisa: Edizioni ETS. Harrison, R. 1995. Consultant's Journey. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass Raine, N. 1998. After Silence: Rape and My Journey Back. New York: Crown. Todhunter, C. 2001. "Undertaking Action Research: Negotiating the Road Ahead", Social Research Update, Issue 34, Autumn. Philosophical sources Abram, D. 1996. The Spell of the Sensuous. New York: Vintage. Argyris, C. Putnam, R. & Smith, D. 1985. Action Science: Concepts, methods and skills for research and intervention. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. Gadamer, H. 1982. Truth and Method. New York: Crossroad. Habermas, J. 1984/1987. The Theory of Communicative Action, Vol.s I & II. Boston:Beacon. Hallward, P. 2003. Badiou: A subject to truth. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. Lewin, G.W. (Ed.) (1948). Resolving social conflicts. New York, NY: Harper & Row. (Collection of articles by Kurt Lewin) Lewin, K. (1946) "Action research and minority problems". J Soc. Issues 2(4): 34–46. Malin, S. 2001. Nature Loves to Hide: Quantum physics and the nature of reality, a Western perspective. Oxford: Oxford University Press. McNiff, J. (2013) Action Research: Principles and practice. New York: Routledge. Polanyi, M. 1958. Personal Knowledge. New York: Harper. Senge, P. 1990. The Fifth Discipline. New York: Doubleday Currency. Torbert, W. 1991. The Power of Balance: Transforming Self, Society, and Scientific Inquiry. Varela, F., Thompson, E. & Rosch E. 1991. The Embodied Mind: Cognitive science and human experience. Cambridge MA: MIT Press. Whitehead, J. & McNiff, J. (2006) Action Research Living Theory, London; Sage. ISBN 978-1-4129-0855-9. Wilber, K. 1998. The Marriage of Sense and Soul: Integrating science and religion. New York: Random House Zuber-Skerritt, O., & Wood, L. (2019). Action Learning and Action Research: Genres and Approaches. Emerald (UK). Scholarly journals Action Research The Journal of Applied Behavioral Science Management Learning |

書誌 一般的な情報源 アトキンス L & ウォレス S. (2012). 教育における質的研究。ロンドン:セージ出版。 Burns, D. 2007. Systemic Action Research: システム全体を変えるための戦略。ブリストル: Policy Press. Burns, D. 2015. Navigating complexity in international development: 規模における持続可能な変化を促進する。Rugby: Practical Action Davison, R., Martinsons, M., & Kock, N. (2004). Information Systems Journal, 14(1), 65-86. Greenwood, D. J. & Levin, M., Introduction to Action Research: Social Research for Social Change, Thousand Oaks, California: Sage Publications, 1998. Greenwood, D. J. & Levin, M., Introduction to Action Research. 第2版、カリフォルニア州サウザンド・オークス:セージ出版、2007年。 Martyn Hammersley, 「Action research: a contradiction in terms?」, Oxford Review of Education, 30, 2, 165-181, 2004. James, E. Alana; Milenkiewicz, Margaret T.; Bucknam, Alan. 教育リーダーシップのための参加型アクション・リサーチ: データ主導の意思決定を使って学校を改善する。Thousand Oaks: Sage, 2007. ISBN 978-1-4129-3777-1 Noffke, S. & Somekh, B. (Ed.) (2009) The SAGE Handbook of Educational Action Research. London: SAGE. ISBN 978-1-4129-4708-4. Pine, Gerald J. (2008). Teacher Action Research: Building Knowledge Democracies, Sage Publications. Reason, P. & Bradbury, H., (Ed.) The SAGE Handbook of Action Research. 参加型探究と実践。第1版。London: Sage, 2001. 第2版、2007年、ISBN 978-1-4129-2029-2)。 Rowell, L., Bruce, C., Shosh, J. M., & Riel, M. (2017). The Palgrave international handbook of action research. New York, NY: Palgrave Macmillan. Sherman & Torbert, Transforming Social Inquiry, Transforming Social Action: 大学やコミュニティにおける理論と実践の溝を越えるための新しいパラダイム。ボストン、クルーワー、2000年 Silverman, Robert Mark, Henry L. Taylor Jr. and Christopher G. Crawford. 2008. 「The Role of Citizen Participation and Action Research Principles in Main Street Revitalization: An Analysis of a Local Planning Project", Action Research 6(1): 69-93. Sagor, R. (2010). プロフェッショナルのための共同アクション・リサーチ。Learning Communities. ブルーミントン: Solution Tree Press. Stringer, E.T. And Ortiz, A. (2021). Action Research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications. Wood, L., Zuber-Skerritt, O. (2013). 「教育学部によるコミュニティ参画のための方法論としてのPALAR」。南アフリカ教育ジャーナル, 33, 1-15. Wood, L. (2017) 「高等教育におけるコミュニティ開発:コミュニティに根ざした研究が変化をもたらすことを学者はどのように確認するか?」. Community Development Journal, Volume 52, Issue 4, Pages 685-701, https://doi.org/10.1093/cdj/bsv068. Zuber-Skerritt, O., & Wood, L. (2019). アクション・ラーニングとアクション・リサーチ: Genres and Approaches. Emerald (UK). Woodman & Pasmore. Research in Organizational Change & Development シリーズ。Greenwich CT: Jai Press. 模範と方法論的考察 Argyris, C. 1970. Intervention Theory and Method. Reading, Massachusetts: Addison-Wesley. Argyris, C. 1980. 厳密な研究の内なる矛盾. カリフォルニア州サンディエゴ: Academic Press. Argyris, C. 1994. 行動のための知識. カリフォルニア州サンフランシスコ: Jossey-Bass. Cameron, K. & Quinn, R. 1999. 組織文化の診断と変革。マサチューセッツ州レディング: Addison-Wesley. Center for Collaborative Action Research. 2022. アクション・リサーチ・チュートリアル https://www.ccarweb.org/ Denscombe M. 2010. グッド・リサーチ・ガイド: 小規模社会調査プロジェクトのために(第4版). Open University Press. Berkshire, GBR. ISBN 978-0-3352-4138-5. Dickens, L., Watkins, K. 1999. 「Management Learning, Action Research: ルインを再考する」。第30巻、第2号、127-140頁。<https: //doi.org/10.1177/1350507699302002> Freire, P. 1970. 被抑圧者の教育学『』. New York: Herder & Herder. Garreau, J. 2005. Radical Evolution: 私たちの心、私たちの体、そして人間であることの意味を強化することの約束と危険。ニューヨーク: Doubleday. Heikkinen, H., Kakkori, L. & Huttunen, R. 2001. 「これは私の真実です、あなたの真実を教えてください:真実理論に照らしたアクションリサーチの質のいくつかの側面」。Educational Action Research 1/2001. Heron, J. 1996. Cooperative Inquiry: 人間の条件に関する研究。ロンドン:セージ。 Kemmis, Stephen and McTaggart Robin (1982) The action research planner. Geelong: Deakin University. Kemmis, Stephen, McTaggart, Robin and Nixon, Rhonda (2014) The action research planner. Doing critical participatory action research. Springer. McNiff, J. & Whitehead, J. (2006) All You Need To Know About Action Research, London; Sage. Ogilvy, J. 2000. より良い未来を創造する: より良い明日のためのツールとしてのシナリオ・プランニング。オックスフォード: オックスフォード大学出版局。 Reason, P. & Rowan, J. 1981. Human Inquiry: A Sourcebook of New Paradigm Research. ロンドン: Wiley. Reason, P. 1995. 人間探求における参加。ロンドン:セージ。 シャイン、E. 1999年。Process Consultation Revisited. Reading, Massachusetts: Addison-Wesley. センゲ, P., シャルマー, C., ジャウォルスキー, J., & フラワーズ, B. 2004. プレゼンス: 人間の目的と未来のフィールド。マサチューセッツ州ケンブリッジ: Society for Organizational Learning. Susman G.I. and Evered R.D., 1978. 「Administrative Science Quarterly, An Assessment of the Scientific Merits of Action Research". Vol.23, No.4, pp.582-603 JSTOR 2392581. Torbert, W. & Associates 2004. Action Inquiry: タイムリーで変革的なリーダーシップの秘訣。 一人称の研究/実践例 Bateson, M. 1984. With a Daughter's Eye: A Memoir of Margaret Mead and Gregory Bateson. ニューヨーク: Plume/Penguin. Cuomo, N. (1982). ボローニャ:ヌォーヴァ・コーポレーション. Bologna: Nuova Casa Editrice L. Capelli. Cuomo, N. (2007). 「知る 」という感情の学校へ。未来の教育者、未来の教育者。Pisa: Edizioni ETS. Harrison, R. 1995. コンサルタントの旅。サンフランシスコ: Jossey-Bass Raine, N. 1998. After Silence: Rape and My Journey Back. ニューヨーク: クラウン。 Todhunter, C. 2001. 「アクション・リサーチの実施: ソーシャル・リサーチ・アップデート』第34号、秋。 哲学的資料 Abram, D. 1996. The Spell of the Sensuous. ニューヨーク: Vintage. Argyris, C. Putnam, R. & Smith, D. 1985. 行動科学: 研究と介入のための概念、方法、技能。サンフランシスコ: Jossey-Bass. Gadamer, H. 1982. 真理と方法。New York: Crossroad. Habermas, J. 1984/1987. コミュニケーション行為論』上・下巻。Boston:Beacon. Hallward, P. 2003. Badiou: 真理への主体性. ミネアポリス: University of Minnesota Press. Lewin, G.W. (Ed.) (1948). 社会的葛藤の解決。New York, NY: Harper & Row. (クルト・ルーウィンの論文集) Lewin, K. (1946) 「Action Research and minority problems」. J Soc. Issues 2(4): 34-46. Malin, S. 2001. Nature Loves to Hide: Quantum physics and the nature of reality, a Western perspective. オックスフォード: Oxford University Press. McNiff, J. (2013) Action Research: Principles and practice. New York: Routledge. Polanyi, M. 1958. Personal Knowledge. ニューヨーク:ハーパー センゲ, P. 1990. 第五の規律. ニューヨーク: Doubleday Currency. トーバート、W. 1991. バランスの力: 自己、社会、科学的探究を変革する。 Varela, F., Thompson, E. & Rosch E. 1991. 身体化された心: 認知科学と人間の経験。ケンブリッジ・マサチューセッツ工科大学出版局。 Whitehead, J. & McNiff, J. (2006) Action Research Living Theory, London; Sage. ISBN 978-1-4129-0855-9. ウィルバー, K. 1998. The Marriage of Sense and Soul: Integrating Science and religion. ニューヨーク: ランダムハウス Zuber-Skerritt, O., & Wood, L. (2019). アクション・ラーニングとアクション・リサーチ: Genres and Approaches. Emerald (UK). 学術雑誌 アクション・リサーチ 応用行動科学ジャーナル マネジメント・ラーニング |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Action_research |

★Participatory

action research, PAR

| Participatory

action research (PAR) is an approach to action research emphasizing

participation and action by members of communities affected by that

research. It seeks to understand the world by trying to change it,

collaboratively and following reflection. PAR emphasizes collective

inquiry and experimentation grounded in experience and social history.

Within a PAR process, "communities of inquiry and action evolve and

address questions and issues that are significant for those who

participate as co-researchers".[1] PAR contrasts with mainstream

research methods, which emphasize controlled experimentaction,

statistical analysis, and reproducibility of findings. PAR practitioners make a concerted effort to integrate three basic aspects of their work: participation (life in society and democracy), action (engagement with experience and history), and research (soundness in thought and the growth of knowledge).[2] "Action unites, organically, with research" and collective processes of self-investigation.[3] The way each component is actually understood and the relative emphasis it receives varies nonetheless from one PAR theory and practice to another. This means that PAR is not a monolithic body of ideas and methods but rather a pluralistic orientation to knowledge making and social change.[4][5][6] |

参加型行動研究=参加型アクションリサーチ(PAR)とは、研究対象となるコミュニティの成員によ

る参加と行動を重視する行動研究の手法である。協働と省察を経て世界を変えようとする過程で、世界を理解しようとする。PARは経験と社会史に根ざした集

団的な探究と実験を重視する。PARの過程では、「探究と行動の共同体が形成され、共同研究者として参加する者にとって重要な問題や課題に取り組む」ので

ある。[1] PARは、制御された実験行動、統計分析、結果の再現性を重視する主流の研究手法とは対照的である。 PAR実践者は、自らの活動の三つの基本側面——参加(社会生活と民主主義)、行動(経験と歴史への関与)、研究(思考の妥当性と知識の成長)——を統合 する努力を集中的に行う。[2] 「行動は研究と有機的に結びつき」、集団的な自己探求のプロセスを形成する。[3] ただし、各構成要素の実際の理解や相対的な重視度は、PARの理論と実践によって異なる。これはPARが一元的な思想や方法論の集合体ではなく、むしろ知 識創造と社会変革に向けた多元的な方向性であることを意味する。[4][5][6] |

| Overview In the UK and North America the work of Kurt Lewin and the Tavistock Institute in the 1940s has been influential. However alternative traditions of PAR, begin with processes that include more bottom-up organising and popular education than were envisaged by Lewin. PAR has multiple progenitors and resists definition. It is a broad tradition of collective self-experimentation backed up by evidential reasoning, fact-finding and learning. All formulations of PAR have in common the idea that research and action must be done 'with' people and not 'on' or 'for' people.[1][2][7][8][9][10][11][12][13] It counters scientism by promoting the grounding of knowledge in human agency and social history (as in much of political economy). Inquiry based on PAR principles makes sense of the world through collective efforts to transform it, as opposed to simply observing and studying human behaviour and people's views about reality, in the hope that meaningful change will eventually emerge. PAR draws on a wide range of influences, both among those with professional training and those who draw on their life experience and those of their ancestors. Many draw on the work of Paulo Freire,[14] new thinking on adult education research,[15] the Civil Rights Movement,[16] South Asian social movements such as the Bhumi Sena,[3][17] and key initiatives such as the Participatory Research Network created in 1978 and based in New Delhi. "It has benefited from an interdisciplinary development drawing its theoretical strength from adult education, sociology, political economy, community psychology, community development, feminist studies, critical psychology, organizational development and more".[18] The Colombian sociologist Orlando Fals Borda and others organized the first explicitly PAR conference in Cartagena, Colombia in 1977.[19] Based on his research with peasant groups in rural Boyaca and with other underserved groups, Fals Borda called for the 'community action' component to be incorporated into the research plans of traditionally trained researchers. His recommendations to researchers committed to the struggle for justice and greater democracy in all spheres, including the business of science, are useful for all researchers and echo the teaching from many schools of research: "Do not monopolise your knowledge nor impose arrogantly your techniques, but respect and combine your skills with the knowledge of the researched or grassroots communities, taking them as full partners and co-researchers. Do not trust elitist versions of history and science which respond to dominant interests, but be receptive to counter-narratives and try to recapture them. Do not depend solely on your culture to interpret facts, but recover local values, traits, beliefs, and arts for action by and with the research organisations. Do not impose your own ponderous scientific style for communicating results, but diffuse and share what you have learned together with the people, in a manner that is wholly understandable and even literary and pleasant, for science should not be necessarily a mystery nor a monopoly of experts and intellectuals."[20] PAR can be thought of as a guiding paradigm to influence and democratize the creation of knowledge making, and ground it in real community needs and learning. Knowledge production controlled by elites can sometimes further oppress marginalized populations. PAR can be a way of overcoming the ineffectiveness and elitism of conventional schooling and science, and the negative effects of market forces and industry on the workplace, community life and sustainable livelihoods.[21][22] Fundamentally, PAR pushes against the notion that experiential distance is required for objectivity in scientific and sociological research. Instead, PAR values embodied knowledge beyond "gated communities" of scholarship, bridging academia and social movements such that research and advocacy — often thought to be mutually exclusive — become intertwined.[23] Rather than be confined by academia, participatory settings are believed to have "social value," confronting epistemological gaps that may deepen ruts of inequality and injustice.[24] These principles and the ongoing evolution of PAR have had a lasting legacy in fields ranging from problem solving in the workplace to community development and sustainable livelihoods, education, public health, feminist research, civic engagement and criminal justice. It is important to note that these contributions are subject to many tensions and debates on key issues such as the role of clinical psychology, critical social thinking and the pragmatic concerns of organizational learning in PAR theory and practice. Labels used to define each approach (PAR, critical PAR, action research, psychosociology, sociotechnical analysis, etc.) reflect these tensions and point to major differences that may outweigh the similarities. While a common denominator, the combination of participation, action and research reflects the fragile unity of traditions whose diverse ideological and organizational contexts kept them separate and largely ignorant of one another for several decades.[21][22] The following review focuses on traditions that incorporate the three pillars of PAR. Closely related approaches that overlap but do not bring the three components together are left out. Applied research, for instance, is not necessarily committed to participatory principles and may be initiated and controlled mostly by experts, with the implication that 'human subjects' are not invited to play a key role in science building and the framing of the research questions. As in mainstream science, this process "regards people as sources of information, as having bits of isolated knowledge, but they are neither expected nor apparently assumed able to analyze a given social reality".[15] PAR also differs from participatory inquiry or collaborative research, contributions to knowledge that may not involve direct engagement with transformative action and social history. PAR, in contrast, has evolved from the work of activists more concerned with empowering marginalized peoples than with generating academic knowledge for its own sake.[25][26][27] Lastly, given its commitment to the research process, PAR overlaps but is not synonymous with action learning, action reflection learning (ARL), participatory development and community development—recognized forms of problem solving and capacity building that may be carried out with no immediate concern for research and the advancement of knowledge.[28] |

概要 英国と北米では、1940年代のカート・レヴィンとタヴィストック研究所の活動が影響力を持ってきた。しかしPARの代替的な伝統は、レヴィンが想定した よりも草の根的な組織化や大衆教育を含むプロセスから始まっている。 PARには複数の起源があり、定義を拒む。これは証拠に基づく推論、事実調査、学習によって支えられた集団的自己実験の広範な伝統である。あらゆるPAR の体系に共通するのは、研究と行動は人々「に対して」や「のために」ではなく、人々「と共に」行われなければならないという考え方だ[1][2][7] [8][9][10]。[11][12][13] それは(政治経済学の多くと同様に)人間の主体性と社会史に知識の基盤を置くことで科学主義に対抗する。PARの原則に基づく探究は、単に人間の行動や現 実に対する人民の見解を観察・研究し、意味ある変化がやがて現れることを期待するのではなく、世界を変革するための集団的努力を通じて世界を理解する。 PARは専門的訓練を受けた者から、自身や祖先の人生経験に依拠する者まで、幅広い影響源から汲み取られている。パウロ・フレイレ[14]の著作、成人教 育研究における新たな思考[15]、公民権運動、 [16] ブミ・セナ[3][17] などの南アジアの社会運動、1978年にニューデリーで創設された参加型研究ネットワークなどの主要な取り組みから影響を受けている。「それは、成人教 育、社会学、政治経済学、コミュニティ心理学、コミュニティ開発、フェミニズム研究、批判心理学、組織開発などから理論的強さを引き出す学際的な発展の恩 恵を受けてきた」。[18] コロンビアの社会学者オルランド・ファルス・ボルダらは、1977年にコロンビアのカルタヘナで、初めて明示的にPARに関する会議を開催した。[19] ボヤカ州の農村部の農民グループやその他の恵まれないグループに対する研究に基づき、ファルス・ボルダは、伝統的な訓練を受けた研究者の研究計画に「コ ミュニティ・アクション」の要素を取り入れるよう求めた. 科学分野を含むあらゆる分野において、正義とより大きな民主主義の実現のために闘う研究者たちに対する彼の提言は、すべての研究者にとって有用であり、多 くの研究分野における教えを反映している。 「自分の知識を独占したり、傲慢に自分の技術を押し付けたりしてはならない。研究対象者や草の根コミュニティの知識を尊重し、自分のスキルと組み合わせ、 彼らを完全なパートナーおよび共同研究者として受け入れること。支配的な利益に応えるエリート主義的な歴史や科学の解釈を鵜呑みにせず、対抗的な物語を受 け入れ、それを再構築しようと努めよ。事実を解釈する際に自らの文化だけに依存せず、現地の価値観、特性、信念、芸術を回復し、研究組織による、そして研 究組織との共同行動に活かせ。結果を伝える際に自らの重苦しい科学的スタイルを押し付けるな。共に学んだことを人々へと拡散し共有せよ。完全に理解可能 で、文学的でさえ心地よい方法で。科学は必ずしも神秘でもなければ、専門家や知識人の独占物でもないのだから。」[20] PARは知識創造に影響を与え民主化し、それを現実のコミュニティのニーズと学習に根ざすための指針的パラダイムと考えられる。エリート層が支配する知識 生産は、時に境界化された人々をさらに抑圧する。PARは、従来の教育や科学の非効率性とエリート主義、市場原理や産業が職場・地域生活・持続可能な生計 に及ぼす悪影響を克服する手段となり得る。[21][22] 根本的にPARは、科学的・社会学的研究における客観性に経験的距離が必要だという概念に異議を唱える。むしろPARは、学問の「閉鎖的なコミュニティ」 を超えた体現された知識を重視し、学術と社会運動を橋渡しすることで、しばしば相互排他的と考えられる研究とアドボカシーを相互に絡み合わせる。[23] 学術に閉じ込められるのではなく、参加型環境には「社会的価値」があるとされ、不平等や不正義の固定化を助長する可能性のある認識論的隔たりに立ち向か う。[24] これらの原則とPARの継続的な発展は、職場の問題解決から地域開発・持続可能な生計手段、教育、公衆健康、フェミニスト研究、市民参加、刑事司法に至る まで、幅広い分野に永続的な遺産を残している。ただし、これらの貢献は、臨床心理学の役割、批判的社会思考、PAR理論と実践における組織学習の実用的な 懸念といった核心的問題をめぐる多くの緊張と議論の対象となっている点に留意すべきだ。各アプローチを定義するラベル(PAR、批判的PAR、アクション リサーチ、心理社会学、社会技術分析など)はこうした緊張関係を反映し、類似点よりも相違点が大きいことを示唆している。共通要素である「参加」「行動」 「研究」の組み合わせは、多様なイデオロギー・組織的背景によって数十年にわたり分離され、互いにほとんど認識されなかった伝統の脆弱な統合を映している のだ。[22] 本稿では、PARの三本柱を包含する伝統に焦点を当てる。これら三要素を統合せず、重複する近接アプローチは除外する。例えば応用研究は必ずしも参加型原 則を重視せず、専門家主導で設計・管理される場合が多く、「人間対象」が科学構築や研究課題設定の核心的役割を担うことは想定されない。主流の科学と同様 に、このプロセスは「人民を情報の源、孤立した知識の断片を持つ存在と見なすものの、彼らが特定の社会的現実を分析できるとは期待もされず、明らかに想定 もされていない」のである。[15] PARはまた、変革的行動や社会史への直接的関与を伴わない知識貢献である参加型調査や共同研究とも異なる。対照的にPARは、学術的知識そのものの生成 よりも、周縁化された人々のエンパワーメントに関心を持つ活動家の実践から発展してきた。[25][26][27] 最後に、研究プロセスへのコミットメントという点で、PARはアクションラーニング、アクションリフレクションラーニング(ARL)、参加型開発、コミュ ニティ開発といった問題解決や能力構築の確立された形態と重なる部分はあるが、それらと同義ではない。これらの形態は、研究や知識の進展を直接的な関心事 とせずに実施される可能性がある。[28] |

| Organizational life Action research in the workplace took its initial inspiration from Lewin's work on organizational development (and Dewey's emphasis on learning from experience). Lewin's seminal contribution involves a flexible, scientific approach to planned change that proceeds through a spiral of steps, each of which is composed of 'a circle of planning, action, and fact-finding about the result of the action', towards an organizational 'climate' of democratic leadership and responsible participation that promotes critical self-inquiry and collaborative work.[29] These steps inform Lewin's work with basic skill training groups, T-groups where community leaders and group facilitators use feedback, problem solving, role play and cognitive aids (lectures, handouts, film) to gain insights into themselves, others and groups with a view to 'unfreezing' and changing their mindsets, attitudes and behaviours. Lewin's understanding of action-research coincides with key ideas and practices developed at the influential Tavistock Institute (created in 1947)) in the UK and National Training Laboratories (NTL) in the US. An important offshoot of Tavistock thinking and practise is the sociotechnical systems perspective on workplace dynamics, guided by the idea that greater productivity or efficiency does not hinge on improved technology alone. Improvements in organizational life call instead for the interaction and 'joint optimization' of the social and technical components of workplace activity. In this perspective, the best match between the social and technical factors of organized work lies in principles of 'responsible group autonomy' and industrial democracy, as opposed to deskilling and top-down bureaucracy guided by Taylor's scientific management and linear chain of command.[30][31][32][33][34][35][36] NTL played a central role in the evolution of experiential learning and the application of behavioral science to improving organizations. Process consultation, team building, conflict management, and workplace group democracy and autonomy have become recurrent themes in the prolific body of literature and practice known as organizational development (OD).[37][38] As with 'action science',[39][40][41][42] OD is a response to calls for planned change and 'rational social management' involving a normative human relations movement and approach to worklife in capital-dominated economies.[43] Its principal goal is to enhance an organization's performance and the worklife experience, with the assistance of a consultant, a change agent or catalyst that helps the sponsoring organization define and solve its own problems, introduce new forms of leadership[44] and change organizational culture and learning.[45][46] Diagnostic and capacity-building activities are informed, to varying degrees, by psychology, the behavioural sciences, organizational studies, or theories of leadership and social innovation.[47][48] Appreciative Inquiry (AI), for instance, is an offshoot of PAR based on positive psychology.[49] Rigorous data gathering or fact-finding methods may be used to support the inquiry process and group thinking and planning. On the whole, however, science tends to be a means, not an end. Workplace and organizational learning interventions are first and foremost problem-based, action-oriented and client-centred. |

組織生活 職場におけるアクションリサーチは、ルーウィンの組織開発研究(およびデューイの経験からの学習への重点)から最初の着想を得た。レヴィンの画期的な貢献 は、計画的な変化に対する柔軟かつ科学的なアプローチにある。このアプローチは螺旋状のステップを経て進み、各ステップは「計画、行動、行動結果に関する 事実調査」という循環で構成される。最終的には、批判的自己探求と協働作業を促進する民主的リーダーシップと責任ある参加という組織的「風土」を目指す。 [29] これらの段階は、ルーウィンの基礎技能訓練グループ(Tグループ)における実践の基盤となった。Tグループでは、コミュニティリーダーやグループファシリ テーターがフィードバック、問題解決、ロールプレイ、認知補助(講義、配布資料、映像)を用いて、自己・他者・集団への洞察を深め、思考様式・態度・行動 の「凍結解除」と変容を図る。ルーウィンのアクションリサーチ理解は、英国の有力なタヴィストック研究所(1947年創設)と米国の国立研修研究所 (NTL)で発展した核心的理念・実践と一致する。タヴィストックの思想と実践から派生した重要な概念が、職場の力学に対する社会技術システム論的視点で ある。これは生産性や効率性の向上は技術改良のみに依存しないという考えに導かれている。組織生活の改善には、むしろ職場活動の社会的要素と技術的要素の 相互作用と「共同最適化」が求められる。この視点では、組織化された労働における社会的要因と技術的要因の最良の調和は、「責任ある集団自律」と産業民主 主義の原則にこそ見出され、テイラーの科学的管理法や直線的な指揮系統に基づく技能の低下やトップダウンの官僚主義とは対極にある。[30][31] [32][33][34] [35][36] NTLは、体験学習の進化と組織改善への行動科学応用において中心的な役割を果たした。プロセスコンサルテーション、チームビルディング、紛争管理、職場 における集団民主主義と自律性は、組織開発(OD)として知られる豊富な文献と実践において繰り返し登場するテーマとなった。[37][38]「行動科 学」と同様に、[39][40][41] [42] ODは、規範的人間関係運動や資本主義経済における労働生活へのアプローチを伴う計画的変革と「合理的社会管理」への要請に応えるものである。[43] その主目的は、コンサルタントや変革の仲介者・触媒の支援を得て、組織のパフォーマンスと労働生活の質を向上させることにある。これにより、支援組織は自 らの問題を定義・解決し、新たなリーダーシップ形態を導入[44]、組織文化と学習を変革する。[45][46] 診断活動や能力構築活動は、心理学、行動科学、組織研究、あるいはリーダーシップ理論や社会革新理論などから、程度は様々ながら影響を受けている。 [47][48] 例えばアプレシアティブ・インクワイアリー(AI)は、ポジティブ心理学に基づく参加型研究(PAR)の派生形である。[49] 調査プロセスや集団思考・計画立案を支援するため、厳密なデータ収集や事実調査手法が用いられることもある。しかし全体として、科学は手段であって目的で はない。職場や組織における学習介入は、何よりもまず問題解決型、行動指向型、クライアント中心型である。 |

| Psychosociology Tavistock broke new ground in other ways, by meshing general medicine and psychiatry with Freudian and Jungian psychology and the social sciences to help the British army face various human resource problems. This gave rise to a field of scholarly research and professional intervention loosely known as psychosociology, particularly influential in France (CIRFIP). Several schools of thought and 'social clinical' practise belong to this tradition, all of which are critical of the experimental and expert mindset of social psychology.[50] Most formulations of psychosociology share with OD a commitment to the relative autonomy and active participation of individuals and groups coping with problems of self-realization and goal effectiveness within larger organizations and institutions. In addition to this humanistic and democratic agenda, psychosociology uses concepts of psychoanalytic inspiration to address interpersonal relations and the interplay between self and group. It acknowledges the role of the unconscious in social behaviour and collective representations and the inevitable expression of transference and countertransference—language and behaviour that redirect unspoken feelings and anxieties to other people or physical objects taking part in the action inquiry.[2] The works of Balint,[51] Jaques,[52] and Bion[53] are turning points in the formative years of psychosociology. Commonly cited authors in France include Amado,[54] Barus-Michel,[55][56] Dubost,[57] Enriquez,[58] Lévy,[59][60] Gaujelac,[61] and Giust-Desprairies.[62] Different schools of thought and practice include Mendel's action research framed in a 'sociopsychoanalytic' perspective[63][64] and Dejours's psychodynamics of work, with its emphasis on work-induced suffering and defence mechanisms.[65] Lapassade and Lourau's 'socianalytic' interventions focus rather on institutions viewed as systems that dismantle and recompose norms and rules of social interaction over time, a perspective that builds on the principles of institutional analysis and psychotherapy.[66][67][68][69][70] Anzieu and Martin's[71] work on group psychoanalysis and theory of the collective 'skin-ego' is generally considered as the most faithful to the Freudian tradition. Key differences between these schools and the methods they use stem from the weight they assign to the analyst's expertise in making sense of group behaviour and views and also the social aspects of group behaviour and affect. Another issue is the extent to which the intervention is critical of broader institutional and social systems. The use of psychoanalytic concepts and the relative weight of effort dedicated to research, training and action also vary.[2] |

心理社会学 タヴィストック研究所は他の面でも新たな地平を切り開いた。一般医学と精神医学をフロイト心理学やユング心理学、社会科学と結びつけ、英国軍が様々な人的 資源問題に対処するのを支援したのだ。これにより、心理社会学と広く呼ばれる学術研究と専門的介入の分野が生まれた。特にフランス(CIRFIP)で影響 力を持つ。この伝統にはいくつかの学派や「社会臨床」実践が属し、いずれも社会心理学の実験的・専門家的思考様式を批判している[50]。ほとんどの心理 社会学の理論は、組織開発(OD)と同様に、より大きな組織や制度の中で自己実現や目標達成の問題に対処する個人や集団の相対的自律性と積極的参加を重視 する。この人間主義的・民主主義的課題に加え、心理社会学は精神分析的発想の概念を用いて対人関係や自己と集団の相互作用を扱う。社会的行動や集団的表象 における無意識の役割、そして転移と逆転移の必然的発現——行動探究に参加する他の人々や物理的対象へ、言葉や行動を通じて無言の感情や不安を転嫁する現 象——を認めている。[2] バリント[51]、ジャック[52]、ビオン[53]の著作は、心理社会学の形成期における転換点である。フランスで頻繁に引用される著者にはアマド [54]、バルー=ミシェル[55][56]、デュボスト[57]、アンリケス[58]、レヴィ[59][60]、ゴジェラック[61]、ジュスト=デプ レリー[62]らがいる。異なる思想・実践の流派には、メンデルの「社会精神分析学的」枠組みによる行動研究、ガジェラック[63]、ジュスト=デプレ リー[64]などが含まれる。[59][60] ゴーゼラック[61]、ジュースト=デプレリー[62]らが挙げられる。異なる思想・実践の流派としては、メンデルの「社会精神分析的」視点に基づく行動 研究[63][64]や、労働による苦悩と防衛機制を重視するドジュールによる労働の精神力学がある。[65] ラパサードとルーローの「社会分析」的介入は、むしろ、時間の経過とともに社会的相互作用の規範やルールを解体し、再構成するシステムとして捉えた制度に 焦点を当てている。この視点は、制度分析と心理療法の原則に基づいている。[66][67][68][69][70] アンズィューとマーティン[71] の集団精神分析と集合的「皮膚自我」の理論に関する研究は、一般的にフロイトの伝統に最も忠実であると見なされている。これらの学派と、それらが用いる手 法との主な相違点は、集団の行動や見解、そして集団の行動や感情の社会的側面を理解する上で、分析者が専門知識をどの程度重視するかという点にある。もう 一つの問題は、介入が、より広範な制度や社会システムに対してどの程度批判的であるかという点だ。精神分析の概念の使用や、研究、訓練、行動に割く努力の 相対的な比重も、それぞれ異なる。[2] |

| Applications Community development and sustainable livelihoods PAR emerged in the postwar years as an important contribution to intervention and self-transformation within groups, organizations and communities. It has left a singular mark on the field of rural and community development, especially in the Global South. Tools and concepts for doing research with people, including "barefoot scientists" and grassroots "organic intellectuals" (see Gramsci), are now promoted and implemented by many international development agencies, researchers, consultants, civil society and local community organizations around the world. This has resulted in countless experiments in diagnostic assessment, scenario planning[72] and project evaluation in areas ranging from fisheries[73] and mining[74] to forestry,[75] plant breeding,[76] agriculture,[77] farming systems research and extension,[7][78][79] watershed management,[80] resource mapping,[10][81][82] environmental conflict and natural resource management,[2][83][84][85] land rights,[86] appropriate technology,[87][88] local economic development,[89][90] communication,[91][92] tourism,[93] leadership for sustainability,[94] biodiversity[95][96] and climate change.[97] This prolific literature includes the many insights and methodological creativity of participatory monitoring, participatory rural appraisal (PRA) and participatory learning and action (PLA)[98][99][100] and all action-oriented studies of local, indigenous or traditional knowledge.[101] On the whole, PAR applications in these fields are committed to problem solving and adaptation to nature at the household or community level, using friendly methods of scientific thinking and experimentation adapted to support rural participation and sustainable livelihoods. |

応用分野 地域開発と持続可能な生計手段 PAR(参加型研究)は戦後、集団・組織・地域社会における介入と自己変革への重要な貢献として登場した。特にグローバル・サウスにおいて、農村・地域開 発の分野に独特の足跡を残している。「裸足の科学者」や草の根の「有機的知識人」(グラムシ参照)を含む、人民と共に研究を行うためのツールや概念は、現 在、世界中の多くの国際開発機関、研究者、コンサルタント、市民社会、地域コミュニティ組織によって推進・実施されている。これにより、漁業[73]、鉱 業[74]から林業[75]、植物育種[76]、農業[77]、農業システム研究と普及[7][78][79]、流域管理[80]、資源マッピング [10]、 [81][82]環境紛争と天然資源管理[2][83][84][85]、土地権利[86]、適切な技術[87][88]、地域経済開発[89] [90]、コミュニケーション[91][92]、観光[93]、持続可能性のためのリーダーシップ[94]、生物多様性[95][96]、気候変動といっ た分野で実施されてきた。[97] この豊富な文献には、参加型モニタリング、参加型農村評価(PRA)、参加型学習と行動(PLA)[98][99][100] の多くの洞察と方法論的創造性、そして地域的・先住民的・伝統的知識に関する全ての行動指向的研究が含まれている。[101] 全体として、これらの分野におけるPARの応用は、科学的思考と実験の親しみやすい手法を活用し、農村参加と持続可能な生計を支援するよう適応させなが ら、家庭やコミュニティレベルでの問題解決と自然への適応に取り組んでいる。 |

| Literacy, education and youth In education, PAR practitioners inspired by the ideas of critical pedagogy and adult education are firmly committed to the politics of emancipatory action formulated by Freire,[25] with a focus on dialogical reflection and action as means to overcome relations of domination and subordination between oppressors and the oppressed, colonizers and the colonized. The approach implies that "the silenced are not just incidental to the curiosity of the researcher but are the masters of inquiry into the underlying causes of the events in their world".[14] Although a researcher and a sociologist, Fals Borda also has a profound distrust of conventional academia and great confidence in popular knowledge, sentiments that have had a lasting impact on the history of PAR, particularly in the fields of development,[27] literacy,[102][103] counterhegemonic education as well as youth engagement on issues ranging from violence to criminality, racial or sexual discrimination, educational justice, healthcare and the environment.[104][105][106] When youth are included as research partners in the PAR process, it is referred to as Youth Participatory Action Research, or YPAR.[107] Community-based participatory research and service-learning are a more recent attempts to reconnect academic interests with education and community development.[108][109][110][111][112][113] The Global Alliance on Community-Engaged Research is a promising effort to "use knowledge and community-university partnership strategies for democratic social and environmental change and justice, particularly among the most vulnerable people and places of the world." It calls for the active involvement of community members and researchers in all phases of the action inquiry process, from defining relevant research questions and topics to designing and implementing the investigation, sharing the available resources, acknowledging community-based expertise, and making the results accessible and understandable to community members and the broader public. Service learning or education is a closely related endeavour designed to encourage students to actively apply knowledge and skills to local situations, in response to local needs and with the active involvement of community members.[114][115][116] Many online or printed guides now show how students and faculty can engage in community-based participatory research and meet academic standards at the same time.[117][118][119][120][121][122][123][124][125][126][127][128][129] Collaborative research in education is community-based research where pre-university teachers are the community and scientific knowledge is built on top of teachers' own interpretation of their experience and reality, with or without immediate engagement in transformative action.[130][131][132][133][134][135] |

識字、教育、そして若者 教育において、批判的教育学と成人教育の思想に触発されたPAR実践者は、フリーレが提唱した解放的行動の政治学に強くコミットしている[25]。その焦 点は、ダイアロジックな省察と行動を手段として、抑圧者と被抑圧者、植民者と被植民者との間の支配と従属の関係を克服することにある。このアプローチは 「沈黙を強いられた者たちは、研究者の好奇心の対象として偶発的に存在するのではなく、自らの世界における出来事の根底にある原因を探究する主役である」 [14]ことを示唆している。研究者かつ社会学者であるファルス・ボルダもまた、従来の学界に対する深い不信感と民衆の知識への強い信頼を抱いており、こ うした思想はPARの歴史、特に開発[27]、識字教育、 [102][103] 反ヘゲモニー教育、そして暴力から犯罪性、人種的・性的差別、教育の公正性、医療、環境に至るまで多様な問題への若者の関与において持続的な影響を与えて きた。[104][105][106] 若者をPARプロセスの研究パートナーとして包含する場合、それは「若者の参加型行動研究(YPAR)」と呼ばれる。[107] コミュニティベース参加型研究とサービスラーニングは、学術的関心と教育・地域開発を再接続しようとする比較的新しい試みである。[108][109] [110][111][112][113] グローバル・コミュニティ・エンゲージド・リサーチ連合は、「特に世界で最も脆弱な人民や地域において、民主的な社会・環境変革と正義のために知識と地域 大学連携戦略を活用する」という有望な取り組みである。これは、関連する研究課題やテーマの定義から調査の設計・実施、利用可能な資源の共有、地域に根差 した専門知識の承認、そして結果を地域住民や一般市民が理解できる形で提供することまで、行動探究プロセスの全段階における地域住民と研究者の積極的な関 与を求めるものである。サービスラーニング(サービス学習)またはサービス教育は、地域社会のニーズに応え、地域住民の積極的な参加を得て、学生が知識と 技能を地域の状況に積極的に応用することを促すために設計された、密接に関連する取り組みである。[114][115][116] 現在では多くのオンライン・印刷ガイドが、学生と教員が地域参加型研究に取り組みつつ学術的基準を満たす方法を示している。[117][118] [119][120][121][122][123][124][125] [126][127][128][129] 教育分野における共同研究とは、大学入学前の教師がコミュニティとなり、教師自身の経験と現実の解釈を基盤として科学的知見を構築する地域密着型研究であ る。変革的行動への即時的な関与の有無は問わない。[130][131][132][133][134][135] |

| Public health PAR has made important inroads in the field of public health, in areas such as disaster relief, community-based rehabilitation, public health genomics, accident prevention, hospital care and drug prevention.[136][2]: ch 10, 15 [137][138][139][140][141][142][143] Because of its link to radical democratic struggles of the Civil Rights Movement and other social movements in South Asia and Latin America (see above), PAR is seen as a threat to their authority by some established elites. An international alliance university-based participatory researchers, ICPHR, omit the word "Action", preferring the less controversial term "participatory research". Photovoice is one of the strategies used in PAR and is especially useful in the public health domain. Keeping in mind the purpose of PAR, which is to benefit communities, Photovoice allows the same to happen through the media of photography. Photovoice considers helping community issues and problems reach policy makers as its primary goal.[144] |

公衆衛生 PARは公衆衛生の分野で重要な進展を遂げている。災害救援、地域社会に基づくリハビリテーション、公衆衛生ゲノミクス、事故予防、病院医療、薬物防止な どの領域である。[136][2]: ch 10, 15 [137][138][139][140][141][142] [143] 公民権運動や南アジア・ラテンアメリカの社会運動(前述)における急進的民主主義闘争との関連性から、PARは一部の既得権益層によって権威への脅威と見 なされている。国際的な大学ベースの参加型研究者連合であるICPHRは、「アクション」という語を省略し、より議論の少ない「参加型研究」という用語を 好んで使用している。フォトボイスはPARで用いられる戦略の一つであり、特に公衆衛生分野で有用である。コミュニティの利益を図るというPARの目的を 踏まえ、フォトボイスは写真という媒体を通じてこれを実現する。フォトボイスは、コミュニティの問題や課題を政策決定者に届けることを主要な目標としてい る。[144] |

| Occupational health and safety Participatory programs within the workplace involve employees within all levels of a workplace organization, from management to front-line staff, in the design and implementation of health and safety interventions.[145] Some research has shown that interventions are most successful when front-line employees have a fundamental role in designing workplace interventions.[145] Success through participatory programs may be due to a number of factors. Such factors include a better identification of potential barriers and facilitators, a greater willingness to accept interventions than those imposed strictly from upper management, and enhanced buy-in to intervention design, resulting in greater sustainability though promotion and acceptance.[145][146] When designing an intervention, employees are able to consider lifestyle and other behavioral influences into solution activities that go beyond the immediate workplace.[146] |

労働安全衛生 職場内での参加型プログラムは、管理職から現場スタッフまで、職場組織の全階層の従業員を、健康と安全に関する対策の設計と実施に巻き込むものである。 [145] 一部の研究では、現場従業員が職場対策の設計において基本的な役割を担う場合に、対策が最も成功することが示されている。[145] 参加型プログラムによる成功は、いくつかの要因による可能性がある。具体的には、潜在的な障壁や促進要因のより正確な特定、上層部からの一方的な介入より も高い受容意欲、介入設計への強い賛同が挙げられる。これにより、普及と受容を通じて持続可能性が高まるのである。[145][146] 介入を設計する際、従業員は生活習慣やその他の行動的影響を考慮に入れ、職場の枠を超えた解決策を考案できる。[146] |

| Feminism and gender Feminist research and women's development theory[147] also contributed to rethinking the role of scholarship in challenging existing regimes of power, using qualitative and interpretive methods that emphasize subjectivity and self-inquiry rather than the quantitative approach of mainstream science.[140][148][149][150][151][152][153] As did most research in the 1970s and 1980s, PAR remained androcentric. In 1987, Patricia Maguire critiqued this male-centered participatory research, arguing that "rarely have feminist and participatory action researchers acknowledged each other with mutually important contributions to the journey."[154] Given that PAR aims to give equitable opportunity for diverse and marginalized voices to be heard, engaging gender minorities is an integral pillar in PAR's tenants.[155] In addition to gender minorities, PAR must consider points of intersecting oppressions individuals may experience.[155] After Maguire published Traveling Companions: Feminism, Teaching, And Action Research, PAR began to extend toward not only feminism, but also Intersectionality through Black Feminist Thought and Critical Race Theory (CRT).[155] Today, applying an intersectional feminist lens to PAR is crucial to recognize the social categories, such as race, class, ability, gender, and sexuality, that construct individuals' power relations and lived experiences.[156][157] PAR seeks to recognize the deeply complex condition of human living. Therefore, framing PAR's qualitative study methodologies through an intersectional feminist lens mobilizes all experiences – regardless of various social categories and oppressions – as legitimate sources of knowledge.[158] |

フェミニズムとジェンダー フェミニスト研究と女性開発理論[147]もまた、既存の権力体制への挑戦における学問の役割を再考する一助となった。主流の科学が用いる定量的アプロー チではなく、主体性と自己探求を重視する質的・解釈的手法を用いたのである。[140][148][149][150][151][152] [153] 1970年代から1980年代にかけての研究の大半と同様に、PAR(参加型研究)も男性中心主義のままであった。1987年、パトリシア・マグワイアは この男性中心の参加型研究を批判し、「フェミニスト研究者と参加型行動研究者が、互いの重要な貢献を認め合うことは稀であった」と論じた。[154] PARが多様な声や周縁化された声に公平な発言機会を与えることを目指す以上、ジェンダー的少数派の参加はPARの理念における不可欠な柱である。 [155] ジェンダー的少数派に加え、PARは個人が経験しうる交差する抑圧の点も考慮しなければならない。[155] マグワイアが『旅の仲間たち:フェミニズム、教育、そしてアクションリサーチ』を出版した後、PARはフェミニズムだけでなく、黒人フェミニズム思想や批 判的人種理論(CRT)を通じた交差性(インターセクショナリティ)へと拡大し始めた[155]。今日、PARに交差的フェミニズムのレンズを適用するこ とは、人種、階級、能力、性別、セクシュアリティといった社会的カテゴリーが個人の力関係や生きた経験を構築していることを認識するために不可欠である。 [156][157] PARは人間の生が持つ深く複雑な状態を認識しようとする。したがって、交差性フェミニズムのレンズを通じてPARの質的研究方法論を枠組み化すること は、様々な社会的カテゴリーや抑圧にかかわらず、あらゆる経験を正当な知識源として動員する。[158] |

| Neurodiversity Neurodiversity has contributed to scholarship by including neurodivergent populations within research, by asking neurodivergent adults to get involved in discussing the various stages of the scientific methodology, which allows them to provide a better understanding of the research priorities within these communities.[159][160] This research can challenge the ableist structure within academia where general assumptions (e.g. neurodivergence is inferior to neurotypicality),[161] promote neurodivergent individuals as active collaborators, thus involving them in knowledge generation[162] and ensure the theories of human cognition include strengths and weaknesses, together with lived experiences.[161][163] Additional benefits include co-production and mutuality practices of research, including the promotion of wider epistemic justice, equality in knowledge production, greater relevance of research to lived experience, and greater translational potential of research findings.[164][165][166] |

神経多様性 神経多様性は、研究対象に神経多様性を持つ人々を含めることで学術に貢献してきた。具体的には、神経多様性を持つ成人に科学的方法論の各段階の議論への参 加を求め、それによってこれらのコミュニティにおける研究優先事項への理解を深めることを可能にした。[159][160] この研究は、学界における健常者中心主義の構造(例:神経多様性は神経典型的より劣るという一般的な仮定)[161] に挑戦し、神経多様性を持つ個人を積極的な協力者として位置づける。これにより彼らを知識生成[162] に巻き込み、人間の認知理論が長所と短所、そして実体験を包含することを保証する。[161][163] 追加的な利点として、共同生産と相互性の研究実践が挙げられる。これには、より広範な認識的正義の促進、知識生産における平等性、実体験への研究の関連性 向上、研究成果の応用可能性の拡大が含まれる。[164][165][166] |

| Civic engagement and ICT Novel approaches to PAR in the public sphere help scale up the engaged inquiry process beyond small group dynamics. Touraine and others thus propose a 'sociology of intervention' involving the creation of artificial spaces for movement activists and non-activists to debate issues of public concern.[167][168][169] Citizen science is another recent move to expand the scope of PAR, to include broader 'communities of interest' and citizens committed to enhancing knowledge in particular fields. In this approach to collaborative inquiry, research is actively assisted by volunteers who form an active public or network of contributing individuals.[170][171] Efforts to promote public participation in the works of science owe a lot to the revolution in information and communications technology (ICT). Web 2.0 applications support virtual community interactivity and the development of user-driven content and social media, without restricted access or controlled implementation. They extend principles of open-source governance to democratic institutions, allowing citizens to actively engage in wiki-based processes of virtual journalism, public debate and policy development.[172] Although few and far between, experiments in open politics can thus make use of ICT and the mechanics of e-democracy to facilitate communications on a large scale, towards achieving decisions that best serve the public interest. In the same spirit, discursive or deliberative democracy calls for public discussion, transparency and pluralism in political decision-making, lawmaking and institutional life.[173][174][175][176] Fact-finding and the outputs of science are made accessible to participants and may be subject to extensive media coverage, scientific peer review, deliberative opinion polling and adversarial presentations of competing arguments and predictive claims.[177] The methodology of Citizens' jury is interesting in this regard. It involves people selected at random from a local or national population who are provided opportunities to question 'witnesses' and collectively form a 'judgment' on the issue at hand.[178] ICTs, open politics and deliberative democracy usher in new strategies to engage governments, scientists, civil society organizations and interested citizens in policy-related discussions of science and technology. These trends represent an invitation to explore novel ways of doing PAR on a broader scale.[2] |

市民参加と情報通信技術 公共領域における参加型研究(PAR)への新たなアプローチは、少人数のグループ活動を超えた参加型探究プロセスの拡大を可能にする。トゥーレーヌらはこ のため、運動活動家と非活動家が公共問題について議論するための人工的空間を創出する「介入の社会学」を提唱している。[167][168][169] 市民科学は、より広範な「関心共同体」や特定分野の知識向上に取り組む市民を包含するため、PARの範囲を拡大する最近の動きである。この共同探究アプ ローチでは、研究は積極的に支援するボランティアによって支えられ、彼らは能動的な公衆または貢献者ネットワークを形成する。[170] [171] 科学活動への市民参加促進の取り組みは、情報通信技術(ICT)革命に大きく依存している。Web 2.0アプリケーションは、アクセス制限や管理された実装なしに、仮想コミュニティの相互作用やユーザー主導型コンテンツ・ソーシャルメディアの発展を支 える。これらはオープンソースガバナンスの原則を民主的機関に拡張し、市民が仮想ジャーナリズム、公共討論、政策立案といったウィキベースのプロセスに積 極的に関与することを可能にする。[172] 数こそ少ないが、オープンな政治の実験はICTと電子民主主義の仕組みを活用し、大規模なコミュニケーションを促進することで、公共の利益に最も資する意 思決定の実現を目指せるのである。 同様の精神に基づき、議論的民主主義あるいは審議民主主義は、政治的意思決定・立法・制度運営において、公的議論・透明性・多元主義を求める。[173] [174][175][176] 事実調査と科学の成果は参加者に公開され、広範なメディア報道、科学的ピアレビュー、審議型世論調査、対立する主張や予測的主張の対立的提示の対象となり 得る[177]。この点で市民陪審の手法は興味深い。地域または国民から無作為に選ばれた人民が「証人」に質問する機会を与えられ、共同で当該問題に対す る「判断」を形成する仕組みである。[178] 情報通信技術(ICT)、オープンな政治、審議型民主主義は、政府、科学者、市民社会組織、関心を持つ市民を、科学技術に関する政策議論に巻き込む新たな 戦略をもたらす。これらの潮流は、より広範な規模でPAR(参加型研究)を行う新たな方法を模索するよう促すものである。[2] |

| Criminal justice Compared to other fields, PAR frameworks in criminal justice are relatively new. But growing support for community-based alternatives to the criminal justice system has sparked interest in PAR in criminological settings.[24] Participatory action research in criminal justice includes system-impacted people themselves in research and advocacy conducted by academics or other experts. Because system-impacted people hold experiential knowledge of the conditions and practices of the justice system, they may be able to more effectively expose and articulate problems with that system.[179] Many people who have been incarcerated are also able to share with researchers facets of the justice system that are invisible to the outside world or are difficult to understand without first-hand experience. Proponents of PAR in criminal justice believe that including those most impacted by the justice system in research is crucial because the presence of these individuals precludes the possibility of misunderstanding or compounding harms of the justice system in that research.[23] Participants in PAR may also hold knowledge or education in more traditional academic fields, like law, policy or government that can inform criminological research. But PAR in criminology bridges the epistemological gap between knowledge gained through academia and through lived experience, connecting research to justice reform.[23][24] |

刑事司法 他の分野と比べて、刑事司法におけるPARの枠組みは比較的新しい。しかし、刑事司法制度に代わる地域社会ベースの代替案への支持が高まるにつれ、犯罪学 の分野でPARへの関心が高まっている。[24] 刑事司法における参加型行動研究では、制度の影響を受けた人々自身が、学者やその他の専門家による研究や提言活動に参加する。制度の影響を受けた人々は司 法制度の現状や慣行について経験的知識を持っているため、その制度の問題点をより効果的に暴露し、明確に表現できる可能性がある。[179] 刑務所収容経験の多くの人は、外部からは見えない司法制度の側面や、直接経験なしには理解が難しい側面を研究者と共有できる。刑事司法分野におけるPAR の支持者は、司法制度の影響を最も強く受ける人々を研究に含めることが重要だと考える。なぜなら、こうした個人の存在が、研究における司法制度の誤解や被 害の増幅を防ぐからである。[23] PARの参加者は、法学、政策、行政といったより伝統的な学術分野の知識や教育も有している場合があり、それが犯罪学研究に資する。しかし犯罪学における PARは、学術を通じて得られた知識と実体験を通じて得られた知識との認識論的隔たりを埋め、研究と司法改革を結びつけるのである。[23][24] |

| Ethics Given the often delicate power balances between researchers and participants in PAR, there have been calls for a code of ethics to guide the relationship between researchers and participants in a variety of PAR fields. Norms in research ethics involving humans include respect for the autonomy of individuals and groups to deliberate about a decision and act on it. This principle is usually expressed through the free, informed and ongoing consent of those participating in research (or those representing them in the case of persons lacking the capacity to decide). Another mainstream principle is the welfare of participants who should not be exposed to any unfavourable balance of benefits and risks with participation in research aimed at the advancement of knowledge, especially those that are serious and probable. Since privacy is a factor that contributes to people's welfare, confidentiality obtained through the collection and use of data that are anonymous (e.g. survey data) or anonymized tends to be the norm. Finally, the principle of justice—equal treatment and concern for fairness and equity—calls for measures of appropriate inclusion and mechanisms to address conflicts of interests. While the choice of appropriate norms of ethical conduct is rarely an either/or question, PAR implies a different understanding of what consent, welfare and justice entail. For one thing the people involved are not mere 'subjects' or 'participants'. They act instead as key partners in an inquiry process that may take place outside the walls of academic or corporate science. As Canada's Tri-Council Policy Statement: Ethical Conduct for Research Involving Humans suggests, PAR requires that the terms and conditions of the collaborative process be set out in a research agreement or protocol based on mutual understanding of the project goals and objectives between the parties, subject to preliminary discussions and negotiations.[180] Unlike individual consent forms, these terms of reference (ToR) may acknowledge collective rights, interests and mutual obligations. While they are legalistic in their genesis, they are usually based on interpersonal relationships and a history of trust rather than the language of legal forms and contracts. Another implication of PAR ethics is that partners must protect themselves and each other against potential risks, by mitigating the negative consequences of their collaborative work and pursuing the welfare of all parties concerned.[181] This does not preclude battles against dominant interests. Given their commitment to social justice and transformative action, some PAR projects may be critical of existing social structures and struggle against the policies and interests of individuals, groups and institutions accountable for their actions, creating circumstances of danger. Public-facing action can also be dangerous for some marginalized populations, such as survivors of domestic violence.[24] In some fields of PAR it is believed that an ethics of participation should go beyond avoidance of harm.[24] For participatory settings that engage with marginalized or oppressed populations, including criminal justice, PAR can be mobilized to actively support individuals. An "ethic of empowerment" encourages researchers to consider participants as standing on equal epistemological footing, with equal say in research decisions.[24] Within this ethical framework, PAR doesn't just affect change in the world but also directly improves the lives of the research participants. An "ethic of empowerment" may require a systemic shift in the way researchers view and talk about oppressed communities — often as degenerate or helpless.[24] If not practiced in a way that actively considers the knowledge of participants, PAR can become manipulative. Participatory settings in which participants are tokenized or serve only as sources of information without joint power in decision-making processes can exploit rather than empower. By definition, PAR is always a step into the unknown, raising new questions and creating new risks over time. Given its emergent properties and responsiveness to social context and needs, PAR cannot limit discussions and decisions about ethics to the design and proposal phase. Norms of ethical conduct and their implications may have to be revisited as the project unfolds.[2]: Chapter 8 This has implications, both in resources and practice, for the ability to subject the research to true ethical oversight in the way that traditional research has come to be regulated. |

倫理 参加型研究(PAR)における研究者と参加者の間の力関係はしばしば微妙であるため、様々なPAR分野において研究者と参加者の関係を導く倫理規範が求め られてきた。人間を対象とする研究倫理の規範には、個人や集団が意思決定について熟議し、それに基づいて行動する自律性を尊重することが含まれる。この原 則は通常、研究に参加する者(あるいは意思決定能力を欠く者の場合はその代理人)による自由で、十分な情報に基づく、継続的な同意を通じて表現される。も う一つの主流の原則は、参加者の福祉である。知識の進歩を目的とした研究への参加において、特に深刻かつ発生可能性の高い、利益とリスクの不利なバランス に晒されるべきではない。プライバシーは人民の福祉に寄与する要素であるため、匿名(例:調査データ)または匿名化されたデータの収集・利用を通じて得ら れる機密保持が規範となる傾向がある。最後に、公正の原則——平等な扱いと公平性・衡平性への配慮——は、適切な参加の確保と利益相反に対処する仕組みを 求める。 倫理的行動の適切な規範の選択が二者択一の問題となることは稀だが、PARは同意・福祉・公正が何を意味するかについて異なる理解を暗示する。まず、関与 する人民は単なる「被験者」や「参加者」ではない。むしろ彼らは、学術界や企業科学の枠外で行われる調査プロセスにおける重要なパートナーとして行動す る。カナダの「人間を対象とする研究における倫理的行動に関する三機関政策声明」が示唆するように、PARでは、事前協議と交渉を経て、当事者間のプロ ジェクト目標・目的に関する相互理解に基づき、共同プロセスの条件を研究契約またはプロトコルに明記することが求められる。[180] 個別の同意書とは異なり、こうした業務委託契約書(ToR)は集団的権利・利益・相互義務を認める場合がある。法的起源を持つものの、通常は法的文書や契 約書の文言ではなく、対人関係と信頼の歴史に基づいている。 PAR倫理のもう一つの含意は、パートナーが共同作業の負の結果を軽減し、関係する全ての当事者の福祉を追求することで、潜在的なリスクから自らと相互を 保護しなければならないことである[181]。これは支配的な利益に対する闘いを妨げるものではない。社会正義と変革的行動へのコミットメントから、一部 のPARプロジェクトは既存の社会構造を批判し、自らの行動に責任を持つ個人・集団・機関の政策や利益と闘い、危険な状況を生み出す可能性がある。公的な 行動は、家庭内暴力の被害者など一部の周縁化された集団にとって危険を伴う場合もある。[24] 一部のPAR分野では、参加の倫理は危害回避を超えていくべきだと考えられている。[24] 刑事司法を含む周縁化・抑圧された集団と関わる参加型環境において、PARは個人を積極的に支援するために活用され得る。「エンパワーメントの倫理」は、 研究者が参加者を認識論的に対等な立場に立つ存在と見なし、研究決定において同等の発言権を持つよう促す。[24] この倫理的枠組みにおいて、PARは単に世界を変えるだけでなく、研究参加者の生活を直接的に改善する。この「エンパワーメントの倫理」は、研究者が抑圧 されたコミュニティを(しばしば退廃的または無力な存在として)見たり語ったりする方法に、体系的な転換を要求するかもしれない。[24] 参加者の知識を積極的に考慮しない形で実践されれば、PARは操作的になり得る。参加者が形だけの存在にされたり、意思決定プロセスにおける共同の権限を 持たずに情報源としてのみ機能する参加型環境は、エンパワーメントではなく搾取をもたらす。 定義上、PARは常に未知への一歩であり、新たな疑問を提起し、時間の経過と共に新たなリスクを生み出す。その創発的特性と社会的文脈・ニーズへの応答性 を考慮すると、PARは倫理に関する議論や決定を設計・提案段階に限定できない。倫理的行動規範とその影響は、プロジェクトの進展に伴い再検討が必要とな る場合がある。[2]:第8章 これは、資源面と実践面の両方で、従来の研究が規制されるようになった方法と同様に、研究を真の倫理的監視下に置く能力に 影響を及ぼす。 |