文系と理系

Humanities versus Natural Sciences

文系と理系

Humanities versus Natural Sciences

このページのねらいは、「世の中の科学には、文系と理系があって、それぞ れ異なった世界がある」という長年にわたってきた我々の常識を破壊するこ とにあります。しかし、それを破壊するためには、まず、これまでの文系と理系というものが、どのように定義されてきたのかを明らかにしなければなりません。そのことを明 らかにしないと、それぞれの専門分野を乗り越える、「学際的」とか「学術横断的」とか「トランスディシプリナリー(=分野横断的)」ということの意義が明 らかにされないからです。

そこでとられる方法は、科学の相対化という手法です。これには認識論的・歴史的・社会学的な相対化というものがありますが、この授業では最後の 社会学的あるいは人類学的な相対化を主にとります。もちろん認識論的および歴史的相対化も重要な手法で、我々の勉強には不可欠な視点でもあり、適宜参考に します。

日本の文系と理系の関係は、戦前の旧制高校の文科、理科という二分法に由来しますが、西洋では古くは大学の学部分類での自由七科(artes liberalis)すなわちリベラルアーツ(文系)と医学や法学などの応用実践学との対立の中で捉えられてきました。しかし、文系的応用専門科目(法 学)と理科と理系的応用専門科目(医学)を学ぶための前段階として、リベラルアーツ(文理融合の教養科目群)を学んでおかねばなりませんでした。したがっ て、文系と理系の違いは、専門分化したそれぞれの大家たちから、リベラルアーツ(文理融合の教養科目群)は必要だ、いやもういらないという論争のなかで、 対立化されてきました。

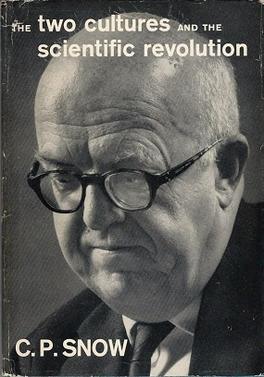

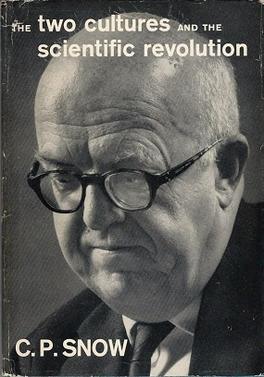

C.P.スノー(C. P. Snow, 1905-1980)が説く「人文系/理系」の対立がその中でも最も有名なものです。

"I believe the intellectual life of the whole of western society is increasingly being split into two polar groups.... Two polar groups: at one pole we have the literary intellectuals, who incidentally while no one was looking took to referring to themselves as 'intellectuals' as though there were no others." (Snow 1961:4)

「西洋社会全体の知的生活は、ますます二つの極に分かれてきていると思う。一方の極には文学知識人がいて、彼らは誰も見ていない間に、自分たちのことを 「知識人 」と呼ぶようになった。(スノー 1961:4)

"Literary intellectuals at one pole-at the other scientists, and as the most representative, the physical scientists. Between the two a gulf of mutual incomprehension-sometimes (particularly among the young) hostility and dislike, but most of all lack of understanding. They have a curious distorted image of each other. Their attitudes are so different that, even on the level of emotion, they can't find much common ground. Non-scientists tend to think of scientists as brash and boastful." (Snow 1961:4-5)

「一

方の極に文学知識人、もう一方の極に自然科学者、そして最も代表的なのが物理科学者である。両者の間には相互理解の溝があり、時には(特に若者の間では)

敵意や嫌悪を抱くこともある。彼らはお互いに不思議な歪んだイメージを持っている。両者の考え方はあまりに異なり、感情的なレベルでさえ、共通点を見出す

ことはできない。非科学者は科学者を生意気で自慢げだと思いがちである。(スノー 1961:4-5)

"On the other hand, the scientists believe that the literary intellectuals are totally lacking in foresight, peculiarly unconcerned with their brother men, in a deep sense anti-intellectual, anxious to restrict both art and thought to the existential moment." (Snow 1961:5-6)

「他方、科学者たちは、文学的知識人には先見の明がまったくなく、同胞である人間には無関心で、深い意味で反知性的で、芸術も思想も実存的な瞬間に限定したがるものだと考えている」(Snow 1961:5-6)。(スノー1961:5-6)

"It was through living among these groups. and much more, I think, through moving regularly from one to the other and back again that I got occupied with the problem of what, long before I put it on paper, I christened to myself as the 'two cultures'."(Snow 1961:2)

「これらの集団の中で生活することによって、そしてそれ以上に、定期的に一方から他方へと移動し、また戻ってくることによって、私はこの問題に夢中になったのだと思う」(Snow 1961:2)。

| "The Two Cultures"[1]

is the first part of an influential 1959 Rede Lecture by British

scientist and novelist C. P. Snow, which was published in book form as

The Two Cultures and the Scientific Revolution the same year.[2][3] Its

thesis was that science and the humanities, which represented "the

intellectual life of the whole of western society", had become split

into "two cultures" and that this division was a major handicap to both

in solving the world's problems. |

『二つの文化』[1]は、英国の科学者であり小説家でもあるC.P.ス

ノウが1959年に行ったレデ講演の冒頭部分で、同年「二つの文化と科学革命」として書籍化された[2][3]。そのテーゼは、「西洋社会全体の知的生

活」を代表する自然科学と人文科学が「二つの文化」に分裂しており、この分裂が世界の問題を解決する上で両者に大きなハンディキャップとなっているという

ものだった。 |

| The lecture The talk was delivered 7 May 1959 in the Senate House, Cambridge, and subsequently published as The Two Cultures and the Scientific Revolution. The lecture and book expanded upon an article by Snow published in the New Statesman of 6 October 1956, also entitled "The Two Cultures".[4] Published in book form, Snow's lecture was widely read and discussed on both sides of the Atlantic, leading him to write a 1963 follow-up, The Two Cultures: And a Second Look: An Expanded Version of The Two Cultures and the Scientific Revolution.[5] Snow's position can be summed up by an often-repeated part of the essay: A good many times I have been present at gatherings of people who, by the standards of the traditional culture, are thought highly educated and who have with considerable gusto been expressing their incredulity at the illiteracy of scientists. Once or twice I have been provoked and have asked the company how many of them could describe the Second Law of Thermodynamics. The response was cold: it was also negative. Yet I was asking something which is the scientific equivalent of: Have you read a work of Shakespeare's?[6] I now believe that if I had asked an even simpler question – such as, What do you mean by mass, or acceleration, which is the scientific equivalent of saying, Can you read? – not more than one in ten of the highly educated would have felt that I was speaking the same language. So the great edifice of modern physics goes up, and the majority of the cleverest people in the western world have about as much insight into it as their neolithic ancestors would have had.[6] In 2008, The Times Literary Supplement included The Two Cultures and the Scientific Revolution in its list of the 100 books that most influenced Western public discourse since the Second World War.[3] Snow's Rede Lecture condemned the British educational system as having, since the Victorian era, over-rewarded the humanities (especially Latin and Greek) at the expense of scientific and engineering education, despite such achievements having been so decisive in winning the Second World War for the Allies.[7] This in practice deprived British elites (in politics, administration, and industry) of adequate preparation to manage the modern scientific world. By contrast, Snow said, German and American schools sought to prepare their citizens equally in the sciences and humanities, and better scientific teaching enabled these countries' rulers to compete more effectively in a scientific age. Later discussion of The Two Cultures tended to obscure Snow's initial focus on differences between British systems (of both schooling and social class) and those of competing countries.[7] |

講演 講演は1959年5月7日にケンブリッジのセネート・ハウスで行われ、その後『二つの文化と科学革命』として出版された。この講演と書籍は、1956年 10月6日付の『ニュー・ステーツマン』誌に掲載されたスノウの「二つの文化」というタイトルの記事を発展させたものであった[4]。書籍として出版され たスノウの講演は、大西洋の両岸で広く読まれ、議論された: And a Second Look: An Expanded Version of The Two Cultures and the Scientific Revolution』である[5]。 スノーの立場は、このエッセイのよく繰り返される部分に要約されている: 私は、伝統的な文化の基準からすれば、高度な教育を受けたと思われる人々の集まりに何度も出席し、彼らはかなり意気揚々と、科学者の無教養を信じられない と表明してきた。一度や二度、私は挑発に乗り、彼らの中に熱力学第二法則を説明できる者が何人いるか尋ねたことがある。反応は冷たく、否定的だった。しか し、私は科学的な質問をしたのである: シェイクスピアの作品を読んだことがありますか」[6] といった、科学的には「字が読めますか」という質問に相当するような、もっと単純な質問、たとえば「質量や加速度とはどういう意味ですか」と尋ねていた ら、10人に1人以上は読めなかっただろう。- 高学歴者の10人に1人も、私が同じ言葉を話していると感じなかっただろう。こうして、現代物理学の大建築が立ち上がり、西欧諸国の賢い人々の大多数は、 新石器時代の祖先が持っていたであろうのと同じくらいの洞察力を持っている[6]。 2008年、『タイムズ・リテラリー・サプリメント』誌は、第二次世界大戦以降、西洋の公論に最も影響を与えた100冊の本のリストに『二つの文化と科学革命』を含めた[3]。 スノーのRede Lectureは、イギリスの教育制度が、ヴィクトリア朝時代以来、科学技術教育を犠牲にして人文科学(特にラテン語とギリシャ語)を過剰に評価してきた と非難した。対照的に、ドイツとアメリカの学校は、科学と人文科学において平等に市民を準備しようと努め、より良い科学教育によって、これらの国の統治者 は科学時代においてより効果的に競争することができたとスノーは述べている。後に『二つの文化』について論じられるようになると、スノウが当初焦点を当て ていたイギリスの制度(学校教育と社会階級の両方)と競合する国々の制度との違いが不明瞭になりがちであった[7]。 |

| Implications and influence The literary critic F. R. Leavis called Snow a "public relations man" for the scientific establishment in his essay Two Cultures?: The Significance of C. P. Snow, published in The Spectator in 1962. The article attracted a great deal of negative correspondence in the magazine's letters pages.[8] In his 1963 book Snow appeared to revise his thinking and was more optimistic about the potential of a mediating third culture. This concept was later picked up in John Brockman's The Third Culture: Beyond the Scientific Revolution. Introducing a reprint of The Two Cultures, Stefan Collini has argued that the passage of time has done much to reduce the cultural divide Snow noticed, but has not removed it entirely.[citation needed] Stephen Jay Gould's The Hedgehog, the Fox, and the Magister's Pox provides a different perspective. Assuming the dialectical interpretation, it argues that Snow's concept of "two cultures" is not only off the mark, it is a damaging and short-sighted viewpoint, and that it has perhaps led to decades of unnecessary fence-building. Simon Critchley, in Continental Philosophy: A Very Short Introduction suggests:[9] [Snow] diagnosed the loss of a common culture and the emergence of two distinct cultures: those represented by scientists on the one hand and those Snow termed 'literary intellectuals' on the other. If the former are in favour of social reform and progress through science, technology and industry, then intellectuals are what Snow terms 'natural Luddites' in their understanding of and sympathy for advanced industrial society. In Mill's terms, the division is between Benthamites and Coleridgeans. That is, Critchley argues that what Snow said represents a resurfacing of a discussion current in the mid-nineteenth century. Critchley describes the Leavis contribution to the making of a controversy as "a vicious ad hominem attack"; going on to describe the debate as "a familiar clash in English cultural history" citing also T. H. Huxley and Matthew Arnold.[10][11] In his opening address at the Munich Security Conference in January 2014, the Estonian president Toomas Hendrik Ilves said that the current problems related to security and freedom in cyberspace are the culmination of absence of dialogue between "the two cultures": "Today, bereft of understanding of fundamental issues and writings in the development of liberal democracy, computer geeks devise ever better ways to track people... simply because they can and it's cool. Humanists on the other hand do not understand the underlying technology and are convinced, for example, that tracking meta-data means the government reads their emails."[12] |

意味合いと影響 文芸評論家のF・R・リーヴィスは、エッセイ『Two Cultures? The Significance of C. P. Snow(C.P.スノウの意義)」というエッセイを1962年に『スペクテイター』誌に発表した。この記事は同誌のレターページで多くの否定的な反響を 呼んだ[8]。 1963年の著書で、スノウは自身の考えを改め、第三の文化を媒介する可能性についてより楽観的であるように見えた。この概念は後にジョン・ブロックマン の『第三の文化』(The Third Culture)で取り上げられることになる: Beyond the Scientific Revolution(科学革命を超えて)』で取り上げられている。The Two Cultures』の再版を紹介したステファン・コリーニは、時間の経過はスノーが気づいていた文化的な隔たりを大きく縮めたが、完全に取り除いたわけで はないと論じている[要出典]。 スティーブン・ジェイ・グールドの『The Hedgehog, the Fox, and the Magister's Pox』は異なる視点を提供している。弁証法的解釈を前提に、スノーの「2つの文化」という概念は的外れであるだけでなく、有害で近視眼的な視点であり、 おそらく何十年にもわたる不必要な柵作りにつながったと論じている。 サイモン・クリッチリーは『大陸哲学』の中で次のように述べている: A Very Short Introduction』の中で、次のように述べている[9]。 [スノーは)共通の文化が失われ、一方で科学者に代表される文化、他方でスノーが「文学的知識人」と呼ぶ2つの異なる文化が出現したと診断した。前者が科 学、技術、産業を通じた社会改革と進歩に賛成であるとすれば、知識人は、先進工業社会に対する理解と共感において、スノーが言うところの「自然なラッダイ ト」である。ミルの言葉を借りれば、ベンサム派とコールリッジ派の分裂である。 つまりクリッチリーは、スノーが述べたことは、19世紀半ばに流行していた議論の再浮上を意味すると主張する。クリッチリーはリーヴィスが論争を巻き起こ すことに貢献したことを「悪質な中傷攻撃」と表現し、さらにこの論争をT・H・ハクスリーやマシュー・アーノルドも引き合いに出した「イギリス文化史では お馴染みの衝突」であると述べている[10][11]。 2014年1月に開催されたミュンヘン安全保障会議の冒頭演説で、エストニアのトーマス・ヘンドリック・イルヴェス大統領は、サイバースペースにおける安 全保障と自由に関する現在の問題は、「2つの文化」の間の対話の欠如の結果であると述べた: 「今日、自由民主主義の発展における基本的な問題や著作を理解することなく、コンピューターおたくは人々を追跡するためによりよい方法を考案している。一 方、ヒューマニストは基礎となる技術を理解しておらず、例えば、メタデータを追跡するということは、政府が彼らの電子メールを読むということだと確信して いる」[12]。 |

| Antecedents Contrasting scientific and humanistic knowledge is a repetition of the Methodenstreit of 1890 German universities.[13] A quarrel in 1911 between Benedetto Croce and Giovanni Gentile on the one hand and Federigo Enriques on the other one is believed to have had enduring effects in the separation of the two cultures in Italy and to the predominance of the views of (objective) idealism over those of (logical) positivism.[14] In the social sciences it is also commonly proposed as the quarrel of positivism versus interpretivism.[13] |

前例 科学的知識と人文主義的知識を対比させることは、1890年のドイツの大学におけるMethodenstreitの繰り返しである[13]。 1911年に、一方ではベネデット・クローチェとジョヴァンニ・ジェンティーレ、他方ではフェデリーゴ・エンリケスの間で起きた論争は、イタリアにおける 2つの文化の分離と、(論理的)実証主義に対する(客観的)観念論の優位に、永続的な影響を及ぼしたと考えられている[14]。 社会科学においても、これは一般に実証主義対解釈主義の喧嘩として提唱されている[13]。 |

| Culture war The Third Culture Science wars Consilience: The Unity of Knowledge, a 1998 book written by biologist Edward Osborne Wilson, as an attempt to bridge the gap between "the two cultures" Quarrel of the Ancients and the Moderns Interdisciplinarity, a movement to cross boundaries between academic disciplines, including the divide between "the two cultures" |

文化戦争 第三の文化 科学戦争 コンシリエンス: 1998年、生物学者エドワード・オズボーン・ウィルソンが、「2つの文化 」のギャップを埋める試みとして書いた本。 古代人と現代人の争い 学際性(Interdisciplinarity):「2つの文化」の隔たりを含む学問分野の境界を越えようとする運動。 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Two_Cultures |

教育用リンク

テキスト

参照リンク

参照文献

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

Do not paste, but

[Re]Think our message for all undergraduate

students!!!