モダン先住民の図像表象

images of "indios"

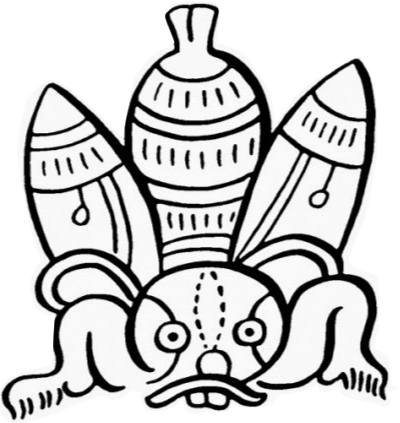

Página interior del libro México a través de los siglos. Vicente Riva Palacio (director), México a través de los siglos, México, Ballescá y Compañía, 1888

Vicente Riva Palacio, El vireinato : historia de la dominación española en México desde 1521-1808.

ラテンアメリカでは19世紀の国民国家形成時に、先住民の多くは(1)国民のメンバーに参入さ れて二級市民扱いされながらも国家形成に欠かせない人民として取り扱われるようになった。そして同時に、(2)白人(クリオーリョ[=クレオール]やメス ティーソ[混血])の支配者は、先住民文化を国民国家建設のシンボルや栄光のある「祖先の姿」として、新古典派的芸術のスタイルを用いて表現される、全国 の公共施設にモニュメントとして飾られるようになった[先住民の文化を考古学資料と共に展示する国立博物館の建設も同時期[1830年前後]である]。ま た、植民地期に抵抗した先住民は、スペインからの独立の英雄と同一視されて、その先住民の抵抗像が独立期のクリオージョの独立の英雄と類似のシンボルに なった。他方、そのようなイメージから外れる先住民は、スペイン植民地期同様、近代国民国家体制のなかで、被抑圧民あるいは二級市民として権力の埒外の地 位に留め置かれた。ラテンアメリカのクリオージョ(クレオール)のエリートたちは、このようにして、先住民像をナショナリズムの神話として取り入れていくことになった(→「クレオール・ナショナリズム」「想像の共同体」「南北アメリカ大陸の脱植民地化」)

☆

| The return of the native :

Indians and myth-making in Spanish

America,

1810-1930 / Rebecca

Earle, Durham [N.C.] : Duke University Press , 2007[pdf] Why does Argentina’s national anthem describe its citizens as sons of the Inca? Why did patriots in nineteenth-century Chile name a battleship after the Aztec emperor Montezuma? Answers to both questions lie in the tangled knot of ideas that constituted the creole imagination in nineteenth-century Spanish America. Rebecca Earle examines the place of preconquest peoples such as the Aztecs and the Incas within the sense of identity—both personal and national—expressed by Spanish American elites in the first century after independence, a time of intense focus on nation-building. Starting with the anti-Spanish wars of independence in the early nineteenth century, Earle charts the changing importance elite nationalists ascribed to the pre-Columbian past through an analysis of a wide range of sources, including historical writings, poems and novels, postage stamps, constitutions, and public sculpture. This eclectic archive illuminates the nationalist vision of creole elites throughout Spanish America, who in different ways sought to construct meaningful national myths and histories. Traces of these efforts are scattered across nineteenth-century culture; Earle maps the significance of those traces. She also underlines the similarities in the development of nineteenth-century elite nationalism across Spanish America. By offering a comparative study focused on Mexico, Guatemala, Colombia, Peru, Chile, and Ecuador, The Return of the Native illustrates both the common features of elite nation-building and some of the significant variations. The book ends with a consideration of the pro-indigenous indigenista movements that developed in various parts of Spanish America in the early twentieth century. |

先住民の帰還:スペイン領アメリカにおけるインディアンと神話構築、

1810-1930年 / レベッカ・アール著、ダーラム[N.C.]:デューク大学出版局、2007年[pdf] なぜアルゼンチンの国歌は国民をインカの息子たちと呼ぶのか?なぜ19世紀チリの愛国者たちは戦艦にアステカの皇帝モンテスマの名を冠したのか?両方の疑 問への答えは、19世紀スペイン領アメリカにおけるクレオール的想像力を構成した複雑に絡み合った思想の結び目に存在する。レベッカ・アールは、独立後最 初の1世紀——国家建設に集中した時代——にスペイン系アメリカ人エリートが表明した人格および国民のアイデンティティ意識の中で、アステカやインカと いった征服以前の民族が占めた位置を検証する。 19世紀初頭の反スペイン独立戦争を起点に、アールは歴史書・詩・小説・切手・憲法・公共彫刻など多様な資料を分析し、エリートナショナリストが先コロン ブス期過去をいかに重要視したかの変遷を辿る。この折衷的な資料群は、スペイン領アメリカ全域のクレオールエリートが、それぞれ異なる手法で意味ある国民 神話と歴史を構築しようとしたナショナリスト的ビジョンを浮き彫りにする。こうした試みの痕跡は19世紀文化の至る所に散見されるが、アールはその痕跡の 重要性を明らかにする。さらにスペイン領アメリカ全域における19世紀エリートナショナリズムの発展に共通点があることも強調する。メキシコ、グアテマ ラ、コロンビア、ペルー、チリ、エクアドルに焦点を当てた比較研究を通じて、『帰郷』はエリートによる国民建設の共通点と重要な差異の両方を浮き彫りにす る。本書は、20世紀初頭にスペイン語圏アメリカ各地で発展した先住民支持のインディヘニスタ運動についての考察をもって締めくくられている。 |

| Acknowledgments vii Introduction On “Indians” 1 Chapter 1 Montezuma’s Revenge 21 Chapter 2 Representing the Nation 47 Chapter 3 “Padres de la Patria”: Nations and Ancestors 79 Chapter 4 Patriotic History and the Pre-Columbian Past 100 Chapter 5 Archaeology, Museums, and Heritage 133 Chapter 6 Citizenship and Civilization: The “Indian Problem” 161 Chapter 7 Indigenismo: The Return of the Native? 184 Epilogue 213 Appendix Abolishing the Indian? 217 A Note on Sources 221 Notes 223 Bibliography 301 Index 353 |

謝辞 vii 序論 「インディアン」について 1 第1章 モンテスマの復讐 21 第2章 国家の表象 47 第3章 「国民の父たち」:国家と祖先 79 第4章 愛国的歴史とコロンブス以前の過去 100 第5章 考古学、博物館、遺産 133 第6章 市民権と文明:「インディアン問題」 161 第7章 インディヘニズモ:先住民の帰還か? 184 エピローグ 213 付録 インディアンへの措置の廃止? 217 出典に関する注記 221 注釈 223 参考文献 301 索引 353 |

☆先住民のシンボル化(図像集)

《先住民[表象]への帰還》の理論的見通し(→出典「再帰的近代化」)

★トランスモダニズム(Transmodernism)

| El transmodernismo

es un movimiento filosófico y cultural fundado por el filósofo

argentino-mexicano Enrique Dussel.1 Para él, el transmodernismo es un

desarrollo del pensamiento desarrollado a partir del modernismo que

sigue y critica al posmodernismo.2 El transmodernismo está influenciado por muchos movimientos filosóficos. Su énfasis en la espiritualidad tiene influencias de los movimientos esotéricos de la época del Renacimiento. También del trascendentalismo, siguiendo a diferentes figuras de los Estados Unidos de mediados del siglo xix y particularmente a Ralph Waldo Emerson. Está también relacionado con la filosofía marxista y con la teología de la liberación católica disidente.3 Filosofía La perspectiva filosófica del transmodernismo contiene elementos tanto del modernismo como del posmodernismo. De hecho, ha sido descrito como "nuevo modernismo" y sus defensores admiran los estilos de vanguardia.4 Basa gran parte de sus fundamentos en la teoría integral de Ken Wilber. El transmodernismo busca revitalizar y modernizar la tradición en lugar de destruirla o reemplazarla. A diferencia del modernismo o el posmodernismo, honra y reverencia la antigüedad y los estilos de vida tradicionales. El transmodernismo critica el pesimismo, el nihilismo, el relativismo y la contrailustración. Abarca, hasta cierto punto, el optimismo, el absolutismo, el fundacionalismo y el universalismo y propone una forma de pensar analógica.3 Movimiento Como movimiento, el transmodernismo pone énfasis en la espiritualidad, las religiones alternativas y la psicología transpersonal. A diferencia del posmodernismo, no está de acuerdo con la secularización de la sociedad. El transmodernismo fomenta la xenofilia y el globalismo, promoviendo la importancia de las diferentes culturas y la apreciación cultural. Propone una cosmovisión antieurocéntrica, antiimperialista y democrática.1 La ecología y la sostenibilidad son también aspectos importantes de este movimiento. Abraza la protección del medio ambiente, valora la vida en el vecindario, la construcción de comunidades, la atención a las personas desfavorecidas, así como el orden y la limpieza. Acepta el cambio tecnológico, pero sólo cuando su objetivo es mejorar las condiciones de vida humanas.5 El transmodernismo adopta posturas firmes sobre el feminismo, el cuidado de la salud, la vida familiar y las relaciones. Promueve la emancipación y los derechos de la mujer, junto con valores familiares morales y éticos tradicionales como la importancia de la familia. Figuras destacadas El transmodernismo es un movimiento filosófico menor en comparación con el posmodernismo y es relativamente nuevo en el hemisferio norte, pero cuenta con figuras filosóficas destacadas. Enrique Dussel es su fundador. Ken Wilber, el inventor de la teoría integral, alega desde un punto de vista transpersonal. Paul Gilroy, un teórico cultural, también ha "respaldado con entusiasmo" el pensamiento transmoderno,3 y Ziauddin Sardar, un erudito islámico, es un crítico del posmodernismo y en muchos casos adopta una forma de pensamiento transmodernista. Además de estos autores, hay otras obras significativas que pueden enmarcarse en este movimiento.67 Véase también Alex Katz Críticas al posmodernismo Remodernismo Transmodernidad https://es.wikipedia.org/wiki/Transmodernismo |

トランスモダニズムは、アルゼンチン系メキシコ人の哲学者エンリケ・

デュッセルによって創設された哲学的・文化的運動である。彼にとってトランスモダニズムとは、モダニズムから発展した思想の展開であり、ポストモダニズム

を追従し批判するものである2。 トランスモダニズムは多くの哲学運動の影響を受けている。スピリチュアリティを重視する点では、ルネサンス時代の秘教運動に影響を受けている。また、19 世紀半ばのアメリカにおける様々な人物、特にラルフ・ウォルドー・エマソンの流れを汲む超越主義からも影響を受けている。また、マルクス主義哲学や反体制 派のカトリック解放神学とも関係がある3。 哲学 トランスモダニズムの哲学的視点は、モダニズムとポストモダニズムの両方の要素を含んでいる。実際、トランスモダニズムは「新しいモダニズム」と形容さ れ、その提唱者は前衛的なスタイルを賞賛している4。 トランスモダニズムは、伝統を破壊したり置き換えたりするのではなく、活性化させ、現代化させようとするものである。モダニズムやポストモダニズムとは異 なり、古代や伝統的なライフスタイルを尊重し、敬う。トランスモダニズムは、悲観主義、ニヒリズム、相対主義、反啓蒙主義を批判する。楽観主義、絶対主 義、基礎主義、普遍主義をある程度受け入れ、類推的な思考法を提案している3。 運動 運動としてのトランスモダニズムは、スピリチュアリティ、代替宗教、トランスパーソナル心理学を重視する。ポストモダニズムとは異なり、社会の世俗化には 同意しない。トランスモダニズムは、異国趣味とグローバリズムを奨励し、異文化と文化的評価の重要性を推進する。反ユーロセントリック、反帝国主義、民主 主義の世界観を提唱している1。 エコロジーと持続可能性もこの運動の重要な側面である。エコロジーと持続可能性もこの運動の重要な側面である。環境保護を受け入れ、近隣の生活、コミュニ ティの形成、恵まれない人々への配慮、秩序と清潔さを重んじる。トランスモダニズムは技術的変化を受け入れるが、その目的が人間の生活環境を改善すること にある場合に限られる5。 トランスモダニズムは、フェミニズム、医療、家族生活、人間関係に強い立場をとる。トランスモダニズムは、フェミニズム、医療、家族生活、人間関係におい て強い立場をとる。トランスモダニズムは、家族の重要性といった伝統的な道徳的・倫理的家族価値とともに、女性の解放と女性の権利を推進する。 主要人物 トランスモダニズムは、ポストモダニズムに比べるとマイナーな哲学運動であり、北半球では比較的新しいが、著名な哲学者がいる。エンリケ・デュッセルはそ の創始者である。インテグラル理論の考案者であるケン・ウィルバーは、トランスパーソナルな視点から論じている。文化理論家のポール・ギルロイもトランス モダン的思考を「熱狂的に支持している」3。イスラム学者のジアウディン・サルダールはポストモダニズムを批判し、多くの場合トランスモダン的思考法を採 用している。これらの著者のほかにも、この運動には重要な著作がある67。 以下も参照のこと。 アレックス・カッツ ポストモダニズム批判 リモダニズム トランスモダニズム あ |

| Transmodernism

is a philosophical and cultural movement founded by Argentinian-Mexican

philosopher Enrique Dussel.[1] He refers to himself as a transmodernist

and wrote a series of essays criticising the postmodern theory and

advocating a transmodern way of thinking. Transmodernism is a

development in thought following the period of postmodernism; as a

movement, it was also developed from modernism, and, in turn, critiques

modernity and postmodernity,[1] viewing them as the end of modernism.

[2] Transmodernism is influenced by many philosophical movements. Its emphasis on spirituality was influenced by the esoteric movements during the Renaissance. Transmodernism is influenced by transcendentalism and idealises different figures from the mid-19th century United States, most notably Ralph Waldo Emerson. Transmodernism is related to different aspects of Marxist philosophy, having common ground with dissident Roman Catholic liberation theology.[3] Philosophies The philosophical views of the transmodernism movement contain elements of both modernism and postmodernism. Transmodernism has been described as "new modernism" and its proponents admire avant-garde styles.[4] It bases much of its core beliefs on the integral theory of Ken Wilber, those of creating a synthesis of "pre-modern", "modern" and "postmodern" realities. In transmodernism, there is a place for both tradition and modernity, and it seeks as a movement to re-vitalise and modernise tradition rather than destroy or replace it. Unlike modernism or postmodernism, the honouring and reverence of antiquity and traditional lifestyles is important in transmodernism. Transmodernism criticises pessimism, nihilism, relativism and the counter-Enlightenment. It embraces, to a limited extent, optimism, absolutism, foundationalism and universalism. It has an analogical way of thinking,[3] viewing things from the outside rather than the inside. Movement As a movement, transmodernism puts an emphasis on spirituality, alternative religions, and transpersonal psychology. Unlike postmodernism, it disagrees with the secularisation of society, putting an emphasis on religion, and it criticises the rejection of worldviews as false or of no importance. Transmodernism places an emphasis on xenophily and globalism, promoting the importance of different cultures and cultural appreciation. It seeks a worldview on cultural affairs and is anti-Eurocentric and anti-imperialist.[1] Environmentalism, sustainability and ecology are important aspects of the transmodern theory. Transmodernism embraces environmental protection and stresses the importance of neighbourhood life, building communities as well as order and cleanliness. It accepts technological change, yet only when its aim is that of improving life or human conditions.[5] Other aspects of transmodernism include democracy and listening to the poor and suffering. Transmodernism takes strong stances on feminism, health care, family life and relationships. It promotes the emancipation of women and female rights, alongside several traditional moral and ethical family values; in particular, the importance of family is stressed. Leading figures Transmodernism is a minor philosophical movement in comparison to postmodernism and is relatively new to the Northern Hemisphere, but it has a large set of leading figures and philosophers. Enrique Dussel is its founder. Ken Wilber, the inventor of Integral Theory, argues from a transpersonal point of view. Paul Gilroy, a cultural theorist, has also "enthusiastically endorsed" transmodern thinking,[3] and Ziauddin Sardar, an Islamic scholar, is a critic of postmodernism and in many cases adopts a transmodernist way of thinking. Essays and works arguing from a transmodernist point of view have been published throughout the years.[6][7] See also Alex Katz Criticism of postmodernism Neomodernism Remodernism Transmodernity |

トランスモダニズムは、アルゼンチン系メキシコ人の哲学者エンリケ・

デュセルによって創始された哲学的・文化的運動である。[1]

彼は自らをトランスモダニストと称し、ポストモダンの理論を批判し、トランスモダンの思考方法を提唱する一連のエッセイを執筆した。トランスモダニズムは

ポストモダニズムの時代に続く思想の発展であり、運動としてはモダニズムから発展し、モダニズムとポストモダニティを批判するものでもある。[1]

それらをモダニズムの終焉と捉えている。[2] トランスモダニズムは多くの哲学運動の影響を受けている。その精神性の強調は、ルネサンス期の秘教的な運動の影響を受けている。トランスモダニズムは超越 論に影響を受け、19世紀半ばのアメリカ合衆国のさまざまな人物、特にラルフ・ウォルドー・エマーソンを理想視している。トランスモダニズムはマルクス主 義哲学のさまざまな側面に関連しており、反対派のローマ・カトリック教会の解放の神学と共通点がある。 哲学 トランスモダニズムの哲学的な見解には、モダニズムとポストモダニズムの両方の要素が含まれている。トランスモダニズムは「新しいモダニズム」と表現され ることがあり、その支持者たちは前衛的なスタイルを賞賛している。[4] トランスモダニズムは、ケン・ウィルバーの「不可欠理論」をその中核的信念の多くに拠っており、その理論は「前近代」、「近代」、「ポストモダン」の現実 を総合的に捉えることを目的としている。 トランスモダニズムでは、伝統と現代性の双方に居場所があり、伝統を破壊したり置き換えたりするのではなく、伝統を再活性化し、現代化する運動として追求 している。モダニズムやポストモダニズムとは異なり、古代や伝統的なライフスタイルを尊重し、崇敬することがトランスモダニズムでは重要である。トランス モダニズムは、悲観主義、ニヒリズム、相対主義、反啓蒙主義を批判する。また、限定的ながら、楽観主義、絶対主義、原理主義、普遍主義を受け入れる。類推 的な思考方法を持ち、物事を内側からではなく外側から見る。 運動 運動として、トランスモダニズムは、精神性、代替宗教、トランスパーソナル心理学を重視する。ポストモダニズムとは異なり、世俗化された社会に反対し、宗 教を重視し、世界観を誤りや重要でないものとして拒絶することを批判する。トランスモダニズムは、異文化への寛容とグローバリズムを重視し、異なる文化や 文化の鑑賞の重要性を推進する。文化的事項に関する世界観を模索し、反西欧主義、反帝国主義である。 環境保護、持続可能性、エコロジーはトランスモダニズム理論の重要な側面である。トランスモダニズムは環境保護を受け入れ、秩序や清潔さだけでなく、近隣 社会の生活の重要性を強調する。技術革新は、生活や人間の状態を改善することが目的である場合にのみ受け入れる。トランスモダニズムのその他の側面には、 民主主義や貧困層や苦しむ人々の意見に耳を傾けることが含まれる。 トランスモダニズムはフェミニズム、ヘルスケア、家庭生活や人間関係について強い立場を取っている。伝統的な道徳的・倫理的な家族の価値観と並んで、女性 の解放や女性の権利を推進しており、特に家族の重要性が強調されている。 主要人物 トランスモダニズムはポストモダニズムと比較するとマイナーな哲学運動であり、北半球では比較的新しいものであるが、多数の主要人物や哲学者がいる。エン リケ・デュセルはその創始者である。トランスパーソナルな視点から議論するインテグラル理論の考案者ケン・ウィルバー。文化理論家のポール・ギルロイもト ランスメディカルな思考を「熱烈に支持」しており[3]、イスラム学者のジアッディーン・サルダールはポストモダニズムの批判者であり、多くの場合トラン スメディカルな思考方法を採用している。 トランスモダニズムの観点から論じたエッセイや著作は、長年にわたって発表されてきた。[6][7] 関連項目 アレックス・カッツ ポストモダニズムの批判 ネオモダニズム リモダニズム トランスモダニティ |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Transmodernism |

+++

リンク

文献

その他の情報

Abbey Road en Chapinlandia por Nicko Hernandez, ca. 2022

Copyleft,

CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099