あなたには愛というものがわからない:バタイユ問題

You don't know what love is: A Bataille's agenda

Santa Lucía de Siracusa, pintor

Francesco del Cossa (c. 1430 – c. 1477)

あなたには愛というものがわからない:バタイユ問題

You don't know what love is: A Bataille's agenda

Santa Lucía de Siracusa, pintor

Francesco del Cossa (c. 1430 – c. 1477)

ご注意!:以下の画面の中には不快で残虐と思

われるような写真があります。

受刑者が苦痛に耐えられるのは、最初に阿片を与える からだといいます。別の写真では、薄ら笑いしているものがありますね。刑を執行する連中は、受刑者が苦痛に苛まれることなどは興味がありません。彼らは拷問的受 刑者=犠牲者の身体をひたすら生きながら毀損するという行為に興奮するのだといいます。これはバタイユ的な蕩尽と通底しますが、彼自身は、このような写真 を机上において「自分の生を『強化』するための試練」として日々ながめていたとい言います。僕は、こんな写真で自分の生命が強くなることは思えません。そ れは宅間守(Mamoru Takuma, 1963-2004)の死を悼んだり、また生前の行状を憎んだりしても、僕の命の強度が試されるのではないと思うのと同じです。この点においては、僕はバ タイユがぜん ぜん理解できませんし、また理解したいとも思えません。

リンク

文献

その他の情報

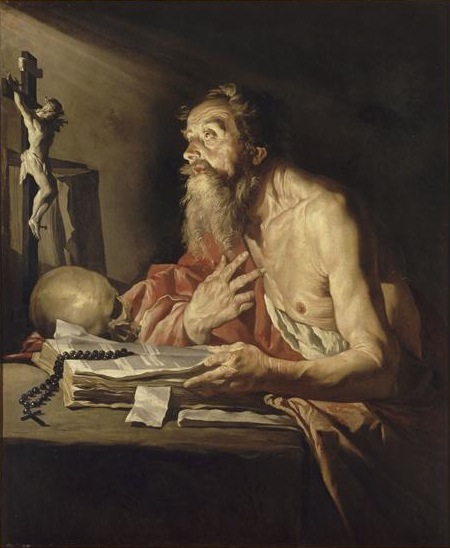

Matthias Stom - Saint Jerome - Nantes

凌遅刑(りょうちけい)とは、清の時代までの中国や李氏朝鮮の時代までの朝鮮半島で処された処刑の方法のひとつ。人間の肉体を少しずつ切り落とし、長時間にわたり激しい苦痛を与えながら死に至らしめる処刑方法で、中国史上最も残酷な刑罰とも評されている。 ca.1902, Qing Dynasty, China - 1905年4月頃の北京における凌遅刑の様子、おそらく傅采漣(Fou-Tchou-Li) 概要 歴代中国王朝が科した刑罰の中でも最も重い刑とされ、反乱の首謀者などに科された。「水滸伝」に凌遅刑の記述が記されている。別名を剮、寸磔とも称し、中 国の史書に「磔死」の語が多く登場するが、いわゆる磔ではなく凌遅[1]を指し、蒸殺が最も重い刑罰とされた李氏朝鮮[2]でも実施された。酷似した処刑 法に隗肉刑がある。 中国 死体を陵辱する刑罰は、有史以前から中国で存在した。「孔子の弟子である子路が反乱で落命し、体を切り刻まれて塩漬けにされる刑罰を受けた」の記述が『史 記』「孔子世家」にあり、漢の時代は、彭越が斬首されて腐敗しないようにその死骸を切り刻まれて塩漬けにされたほか、首を市にさらす棄市という処刑法もあ り、隋の時代に斛斯政もほぼ同様に処刑され、釜茹でにされた。秦、漢、魏晋南北朝、隋唐までは、反乱者も単なる斬首刑で死刑に処すことが原則で、凌遅刑が 法制化されたのは唐滅亡後の五代十国時代である。混迷した中国大陸を統一した宋の時代に、斬首、絞首にならぶ死刑の手段とされたが実施されなかった。これ らの時代は、少数民族が言語や文化・習俗などが大きく異なる圧倒的大多数の漢民族を中央集権的に統治するため、恐怖政治に頼らざるを得なかった征服王朝の 制度も影響し、「長時間苦痛を与えたうえで死に至らす刑」として凌遅刑が政府の刑罰として定着[要出典]した。同じ少数民族同士ではあるが金の時代、モン ゴルのアンバガイ・ハーンに対して「木馬に生きながら手足を釘で打ち付け、全身の皮を剥がす」処刑を執った。明代は袁崇煥が、清代は、国家転覆を企図した 謀反人に対する処刑方法とされた。凌遅刑は貴賤や老若男女問わず重罪人に対し行われている。 この手法は残虐であるとして何度か廃止が建議された。清末に西洋のジャーナリストらがこの刑罰の凄惨な様子を当時の最新機器であった写真などで伝えると 「中国の野蛮な刑罰」と非難された。光緒31年(1905年)に公式に廃止されたが、チベット地方で1910年頃まで行われていたという記録もある [3]。 朝鮮 朝鮮では凌遅処斬(능지처참, 凌遲處斬)または凌遅処死(능지처사, 凌遲處死)と称される。三つの等級に分けられ、一等級は墓に葬られた死体を掘り起こして胴体、腕、脚など六部分に切り取って晒し、二等級は牛を用いて八つ 裂き、三等級は存命のまま皮膚を剥ぐ。高麗の恭愍王の時代に導入され、李氏朝鮮の太宗のほか、世祖や燕山君や光海君の治世でしばしば執行されたとされる。 その後は仁祖により段階的に禁止されたものの、実際は高宗の時代に実施された甲午改革(1894年)に際して廃止された[4]。朝鮮では、罪人への懲罰刑 以外にも呪術として行われ、残虐であるほど呪いの効果が上がると信じられた[要出典]。 凌遅刑にされた人々 唐代 顔杲卿(ただしこれは反乱軍による処刑である) 明代 王山 英宗の信を得て権勢をふるった宦官・王振の甥。王振が主導してオイラトへの無謀な親征を勧め、大敗北を喫し英宗が捕虜になる土木の変の原因を作ったことで于謙らに糾弾され、1449年、王振らの家財没収とともに処刑された。 鄭旺 北京の貧民。鄭旺妖言案の首謀者、正徳帝の母方祖父を自称した。1507年、処刑された。 劉瑾 明代の宦官。皇帝にとり入って国政を壟断したが、皇位簒奪を企てたとして1510年、「凌遅三日」を宣告され、その処刑の経緯は、当時の刑務官による詳細な記録が残されている。 楊金英 嘉靖帝の宮女。壬寅宮変の犯人の一人。1542年、処刑された。 王寧嬪 嘉靖帝の妃嬪。壬寅宮変の主犯とされ、1542年、処刑された。 曹端妃 嘉靖帝の妃嬪。壬寅宮変に直接関与しなかったが内情を知っていたために、1542年、処刑された。 鄭鄤 1639年に崇禎帝の指示により処刑された、科挙を経て官僚になった人物で、派閥争いに巻き込まれ、(強引に?)罪(母を虐待し妹を犯した)を突きつけら れた上に凌遅刑に処された。劉瑾と同じく処刑の詳細が記されている。処刑された後の鄭鄤の肉を拾い販売する業者もいたと記されている。 袁崇煥 斜陽の明にありながら清(後金)の侵攻を何度も撃退し、三国志演義の諸葛亮にも比較されるほどの名将だったが、身内に謀反を疑われて(清による策略)明最後の皇帝である崇禎帝により1630年、処刑された。 李逢 平正成 文禄・慶長の役の露梁海戦で捕らえられた日本人捕虜で島津義弘麾下の武将とされる人物で、その実在は不明。1599年、処刑された。享年40。 平秀政 文禄・慶長の役の露梁海戦で捕らえられた薩摩の日本人捕虜で島津義弘の族姪とされるが、日本側の資料にはその名前は記載されていない。1599年、処刑された。享年27。 清代 耿精忠 清朝の軍人、靖南王。清に対して三藩の乱を起こし失敗。1682年、北京で処刑された。 朱慈煥 明の皇族の末裔。私塾を開いてひっそりと生きていたところ、75歳で捕縛され、「心の中で謀反を考えなかったとは言えない」という罪で1708年、北京で処刑された。 林爽文 台湾で起きた反乱事件・林爽文の乱の指導者。1788年、北京で処刑された。 王阿従 プイ族の女巫。清に対して蜂起の指導者。1797年、北京で処刑された。 林清 天理教の乱の指導者。1813年、北京で処刑された。 李開芳 太平天国の武将。1855年、北京で処刑された。 林鳳祥 太平天国の武将。1855年、北京で処刑された。 陳玉成 太平天国の武将。1862年、河南で処刑された。 張楽行 捻軍の武将。張洛行ともいう。1863年、亳州で処刑された。 蘇天福 捻軍の武将。1863年、北京で処刑された。 石達開 太平天国の「翼王」。成都で部下の曽仕和、黄再忠、韋普成と共に1863年、処刑された。 李秀成 太平天国の「忠王」。1864年、南京で処刑された。 洪天貴福 太平天国の「幼天王」。洪秀全の長男。1864年、南昌で処刑された。15歳を迎える直前の処刑で史上最年少の凌遅刑の受刑者とされる。 頼文光 捻軍の武将。1868年、揚州で処刑された。 張文祥 馬新貽暗殺事件の犯人として1870年、南昌で処刑された。 富珠哩 公式には最後の受刑者として1905年4月10日、北京で処刑された。 呉良輔 福筑力 曾静 雍正帝の代に『大義覚迷録』を批判して、四川総督岳鍾琪を唆して、逮捕されたが助命された。しかし、即位したばかりの乾隆帝によって、北京で処刑された。 [疑問点 – ノート] [1] 王維勤 [疑問点 – ノート] [2] 朝鮮  晒し首にされた金玉均 - 凌遅刑の後、晒し首にされた金玉均 金長孫 壬午事変の首謀者の1人。彼以外に10名以上が同処刑法で処罰された。 金玉均 暗殺された後、朝鮮政府によって遺体がこの刑に処された。写真も現存している。 許筠 光海君に仕えた文人。李氏朝鮮の宮中において内紛が続くなか、讒言によって叛乱計画の首謀者に問われた。 備考 近代以前は、イギリスやフランスにおいても類似した処刑方法が行われていた。詳細については首吊り・内臓抉り・四つ裂きの刑を参照。 脚注 [脚注の使い方] 注釈 出典 ^ 酷刑(王永寛/徳間書店)より。磔の中国語記事は十字架になる。 ^ 朝鮮15代国王の光海君は、王位継承者として自身と対を成す幼い王子の永昌大君を、流刑地の住居に設置されたオンドルを利用して蒸殺した。 ^ “FROM DARKNESS TO DAWN – Jamyang Norbu”. phayul.com (2009年5月19日). 2019年1月19日時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。2021年8月4日閲覧。 ^ http://www.unn.net/ColumnIssue/Detail.asp?nsCode=47641 関連項目 中国法制史 死刑の歴史 外部リンク ウィキメディア・コモンズには、凌遅刑に関連するカテゴリがあります。 "Death by a Thousand Cuts", Harvard University Press Bourgon, Jérôme. "Abolishing 'Cruel Punishments': A Reappraisal of the Chinese Roots and Long-Term Efficiency of the in Legal Reforms." Modern Asian Studies 37, no. 4 (2003): 851-62. |

****

| Lingchi (IPA: [lǐŋ.ʈʂʰɨ̌], Chinese: 凌遲),

usually translated "slow slicing" or "death by a thousand cuts", was a

form of torture and execution used in China from around the 10th

century until the early 20th century. It was also used in Vietnam and

Korea. In this form of execution, a knife was used to methodically

remove portions of the body over an extended period of time, eventually

resulting in death. Lingchi was reserved for crimes viewed as

especially heinous, such as treason. Even after the practice was

outlawed, the concept itself has still appeared across many types of

media.[citation needed] Etymology The word was used to describe the prolonging of a person's agony when the person is being killed. One theory suggests that it grew to be a specific torture technique.[1] An alternative theory suggests that the term originated from the Khitan language, as the penal meaning of the word emerged during the Khitan Liao dynasty.[2] |

凌遅(IPA: [lǐŋ.ʈʂʰɨ̌]、中国語:

凌遲)は通常、「ゆっくりと切り刻む」または「千切りによる死」と訳され、10世紀頃から20世紀初頭まで中国で用いられた拷問および処刑法の一種であ

る。ベトナムや韓国でも用いられた。この処刑法では、ナイフを用いて時間をかけて身体の一部を計画的に切除し、最終的に死に至らしめる。凌遅は、反逆罪な

ど特に悪質と見なされた犯罪に対してのみ用いられた。この処刑法が非合法化された後も、その概念自体は多くの種類のメディアに登場している。 語源 この言葉は、人が殺される際にその苦痛が長引くことを表現するために使われていた。一説によると、それは特定の拷問技術として発展したという。[1] 別の説では、この用語は契丹語に由来し、その刑罰的な意味は契丹の遼王朝の時代に生まれたという。[2] |

| Description Exclamation mark with arrows pointing at each other This article or section appears to contradict itself. Please see the talk page for more information. (May 2024) The process involved tying the condemned prisoner to a wooden frame, usually in a public place. The flesh was then cut from the body in multiple slices in a process that was not specified in detail in Chinese law, and therefore most likely varied. The punishment worked on three levels: as a form of public humiliation, as a slow and lingering death, and as a punishment after death.[citation needed] According to the Confucian principle of filial piety, to alter one's body or to cut the body are considered unfilial practices. Lingchi therefore contravenes the demands of filial piety.[citation needed] In addition, to be cut to pieces meant that the body of the victim would not be "whole" in spiritual life after death.[3] This method of execution became a fixture in the image of China among some Westerners.[citation needed] Lingchi could be used for the torture and execution of a person, or applied as an act of humiliation after death. It was meted out for major offences such as high treason, mass murder, patricide/matricide, or the murder of one's master or employer. (English: petty treason).[4] However, emperors used it to threaten people and sometimes ordered it for minor offences or for family members of their enemies.[5][6] [7][8] [9][10][11][12] While it is difficult to obtain accurate details of how the executions took place, they generally consisted of cuts to the arms, legs, and chest leading to amputation of limbs, followed by decapitation or a stab to the heart. If the crime was less serious or the executioner merciful, the first cut would be to the throat causing death; subsequent cuts served solely to dismember the corpse. Art historian James Elkins argues that extant photos of the execution clearly show that the "death by division" (as it was termed by German criminologist Robert Heindl) involved some degree of dismemberment while the subject was living.[13] Elkins also argues that, contrary to the apocryphal version of "death by a thousand cuts", the actual process could not have lasted long. The condemned individual is not likely to have remained conscious and aware (even if still alive) after one or two severe wounds, so the entire process could not have included more than a "few dozen" wounds. In the Yuan dynasty, 100 cuts were inflicted[14] but by the Ming dynasty there were records of 3,000 incisions.[15][16] It is described as a fast process lasting no longer than 4 or 5 minutes.[17] The coup de grâce was all the more certain when the family could afford a bribe to have a stab to the heart inflicted first.[18] Some emperors ordered three days of cutting[19][20] while others may have ordered specific tortures before the execution,[21] or a longer execution.[22][23][24] For example, records showed that during Yuan Chonghuan's execution, Yuan was heard shouting for half a day before his death.[25] The flesh of the victims may also have been sold as medicine.[26] As an official punishment, death by slicing may also have involved slicing the bones, cremation, and scattering of the deceased's ashes. |

説明 互いに向かい合う矢印付き感嘆符 この記事または節は、自分自身と矛盾しているように見える。詳細はノートページを参照のこと。 (May 2024) 死刑囚を木製の枠に縛り付けるという処刑が行われた。通常は公共の場で行われた。肉は、中国法では詳細に規定されていなかったため、おそらくは様々であっ たと思われるが、その過程で身体から複数回にわたって切り取られた。この処刑は3つのレベルで作用した。すなわち、公開の屈辱、ゆっくりと長引く死、死後 の処罰である。 儒教の「親孝行」の原則によれば、死体を損壊したり、切断したりすることは親不孝と見なされる。そのため、凌遅刑は親孝行の原則に反する。さらに、死体を 切断するということは、死後の精神生活において、被害者の肉体が「完全」ではないことを意味する。この処刑法は、一部の西洋人にとっての中国像に定着し た。 凌遅刑は、拷問や死刑の刑罰として用いられることもあれば、死後の屈辱行為として適用されることもあった。大逆罪、大量殺人、尊属殺人・親族殺人、あるい は主人や雇用主の殺人などの重大な犯罪に対して科された。(英語:軽微な反逆罪)。[4] しかし、皇帝は人々を威嚇するためにこれを用い、時には軽微な犯罪や敵対者の家族に対してこれを命じた。[5][6][7][8][9][10][11] [12] 処刑の正確な詳細を入手するのは困難であるが、処刑は通常、腕、脚、胸への切り込みにより四肢の切断が行われ、その後、斬首または心臓への一突きにより行 われた。犯罪がそれほど深刻でなかった場合や処刑人が慈悲深い場合は、最初の切り込みは喉元に行われ、死に至らしめ、その後の切り込みは死体を解体する目 的のみに行われた。 美術史家のジェームズ・エルキンスは、現存する処刑の写真から、ドイツの犯罪学者ロベルト・ハインドルが「死の分割」(「death by division」)と呼んだ処刑は、ある程度の切断を伴うものであり、被処刑者が生きている間に実行されていたことが明らかであると主張している。 [13] また、エルキンスは、「千の切り傷による死」という俗説とは逆に、実際の処刑は長時間続くことはなかったと主張している。死刑囚は、1つか2つの深い傷を 負った後では、たとえ生きていたとしても、意識を保つことはできなかったであろう。したがって、そのプロセス全体で「数十」以上の傷を負うことはあり得な い。 元の時代には100か所の切り傷が与えられたが[14]、明の時代には3,000か所の切り傷が与えられたという記録がある。[15][16] その処刑は4、5分で終わる迅速な処刑であったと描写されている。[17] 家族が賄賂を払って心臓への一突きを先に与えることができた場合、その処刑はさらに確実なものとなった。。[18] 3日間にわたる切断刑を命じた皇帝もいたが[19][20]、他の皇帝は処刑の前に特定の拷問を命じた可能性もあるし、[21] あるいはより長時間の処刑を命じた可能性もある。[22][23][24] 例えば、元燮環の処刑の際には、死の半日前から元燮環が叫び声をあげていたという記録が残っている。[25] また、処刑された人の肉が薬として売られた可能性もある。[26]公式な処罰として、死を伴う「切り刻む刑」には、骨を切り刻むこと、火あぶり、遺灰を撒くことも含まれていた可能性がある。 |

| Western perceptions The Western perception of lingchi has often differed considerably from actual practice, and some misconceptions persist to the present. The distinction between the sensationalised Western myth and the Chinese reality was noted by Westerners as early as 1895. That year, Australian traveller and later representative of the government of the Republic of China George Ernest Morrison, who claimed to have witnessed an execution by slicing, wrote that "lingchi [was] commonly, and quite wrongly, translated as 'death by slicing into 10,000 pieces' – a truly awful description of a punishment whose cruelty has been extraordinarily misrepresented ... The mutilation is ghastly and excites our horror as an example of barbarian cruelty; but it is not cruel, and need not excite our horror, since the mutilation is done, not before death, but after."[27] According to apocryphal lore, lingchi began when the torturer, wielding an extremely sharp knife, began by cutting out the eyes, rendering the condemned incapable of seeing the remainder of the torture and, presumably, adding considerably to the psychological terror of the procedure. Successive relatively minor cuts chopped off ears, nose, tongue, fingers, toes and genitals preceding cuts that removed large portions of flesh from more sizable parts, e.g., thighs and shoulders. The entire process was said to last three days, and to total 3,600 cuts. The heavily carved bodies of the deceased were then put on a parade for a show in the public.[28] Some victims were reportedly given doses of opium to alleviate suffering.[citation needed] John Morris Roberts, in Twentieth Century: The History of the World, 1901 to 2000 (2000), writes "the traditional punishment of death by slicing ... became part of the western image of Chinese backwardness as the 'death of a thousand cuts'." Roberts then notes that slicing "was ordered, in fact, for K'ang Yu-Wei, a man termed the 'Rousseau of China', and a major advocate of intellectual and government reform in the 1890s".[29] Although officially outlawed by the government of the Qing dynasty in 1905,[30] lingchi became a widespread Western symbol of the Chinese penal system from the 1910s on, and in Zhao Erfeng's administration.[31] Three sets of photographs shot by French soldiers in 1904–05 were the basis for later mythification. The abolition was immediately enforced, and definite: no official sentences of lingchi were performed in China after April 1905.[citation needed] Regarding the use of opium, as related in the introduction to Morrison's book, Meyrick Hewlett insisted that "most Chinese people sentenced to death were given large quantities of opium before execution, and Morrison avers that a charitable person would be permitted to push opium into the mouth of someone dying in agony, thus hastening the moment of decease." At the very least, such tales were deemed credible to Western observers such as Morrison.[citation needed] |

西洋の認識 西洋における凌遅刑に対する認識は、実際の慣行とはしばしば大きく異なり、現在でもいくつかの誤解が残っている。センセーショナルな西洋の神話と中国の現 実の区別は、早くも1895年には西洋人によって指摘されていた。その年、オーストラリア人旅行者で後に中華民国政府代表となったジョージ・アーネスト・ モリソンは、切り刻む刑の執行を目撃したと主張し、「リンチは一般的に、そしてかなり誤って『1万片に切り刻む死刑』と訳されている。これは、その残虐性 が過度に誤って伝えられている刑罰の、実にひどい表現である... この残虐な刑罰は、野蛮な残酷さの例として恐ろしく、私たちの恐怖心を掻き立てる。しかし、この刑罰は残酷ではなく、私たちの恐怖心を掻き立てる必要もな い。なぜなら、この刑罰は死の前ではなく、死の後に行われるからだ。」[27] 外典によると、凌遅刑は、非常に鋭いナイフを振り回す拷問官がまず目をくり抜くことから始まり、死刑囚は残りの拷問を見ることができず、おそらくは、その 処置の心理的恐怖を大幅に増大させた。 その後、耳、鼻、舌、指、足指、性器などを切り落とす比較的軽微な切り傷が続き、太ももや肩など、より大きな部位から肉の大部分を切り取る切り傷が続い た。このプロセス全体は3日間続き、合計3,600回の切開が行われたと言われている。その後、死者の体は大勢の観衆の前で公開処刑として引き回された。 [28] 苦痛を和らげるためにアヘンを投与された被害者もいたと報告されている。[要出典] ジョン・モリス・ロバーツは著書『20世紀:世界の歴史、1901年から2000年』(2000年)の中で、「伝統的な処刑法である切り刻む刑は、西洋の 中国に対する後進性のイメージの一部となり、『千切り殺し』として知られるようになった」と記している。ロバーツは、実際、1890年代に「中国のル ソー」と呼ばれ、知的・政治改革の主要な提唱者であった康有為に対して、切り刻む刑が命じられたと指摘している。[29] 1905年に清国政府によって公式に違法とされたが[30]、凌遅は1910年代以降、趙尔丰の政権下で西洋における中国刑罰制度の象徴として広く知られ るようになった。[31] 1904年から1905年にかけてフランス人兵士によって撮影された3組の写真が、その後の神話化の基礎となった。廃止は即座に実施され、明確なものと なった。1905年4月以降、中国ではリンチの公式判決は下されなかった。[要出典] アヘンの使用に関しては、モリソン著書の序文で関連して述べられているように、メイリック・ヒュレットは「死刑を宣告されたほとんどの中国人は、処刑前に 大量のアヘンを投与されていた」と主張し、モリソンは「慈善家であれば、苦しみながら死を迎えようとしている人の口にアヘンを押し込むことを許可され、死 の瞬間を早めることができる」と主張している。少なくとも、このような話はモリソンなどの西洋の観察者にとっては信憑性のあるものと考えられていた。 |

| History This section relies excessively on references to primary sources. Please improve this section by adding secondary or tertiary sources. (September 2024) (Learn how and when to remove this message)  Execution of Joseph Marchand in Vietnam, 1835 Lingchi existed under the earliest emperors,[citation needed] although similar but less cruel tortures were often prescribed instead. Under the reign of Qin Er Shi, the second emperor of the Qin dynasty, various tortures were used to punish officials.[32][33] The arbitrary, cruel, and short-lived Liu Ziye was apt to kill innocent officials by lingchi.[34] Gao Yang killed only six people by this method,[35] and An Lushan killed only one man.[36][37] Lingchi was known in the Five Dynasties period (907–960 CE); but, in one of the earliest such acts, Shi Jingtang abolished it.[38] Other rulers continued to use it. The method was prescribed in the Liao dynasty law codes,[39] and was sometimes used.[40] Emperor Tianzuo often executed people in this way during his rule.[41] It became more widely used in the Song dynasty under Emperor Renzong and Emperor Shenzong. Another early proposal for abolishing lingchi was submitted by Lu You (1125–1210) in a memorandum to the imperial court of the Southern Song dynasty. Lu You there stated, "When the muscles of the flesh are already taken away, the breath of life is not yet cut off, liver and heart are still connected, seeing and hearing still exist. It affects the harmony of nature, it is injurious to a benevolent government, and does not befit a generation of wise men."[42] Lu You's elaborate argument against lingchi was dutifully copied and transmitted by generations of scholars, among them influential jurists of all dynasties, until the late Qing dynasty reformist Shen Jiaben (1840–1913) included it in his 1905 memorandum that obtained the abolition. This anti-lingchi trend coincided with a more general attitude opposed to "cruel and unusual" punishments (such as the exposure of the head) that the Tang dynasty had not included in the canonic table of the Five Punishments, which defined the legal ways of punishing crime. Hence the abolitionist trend is deeply ingrained in the Chinese legal tradition, rather than being purely derived from Western influences. Under later emperors, lingchi was reserved for only the most heinous acts, such as treason,[43][44] a charge often dubious or false, as exemplified by the deaths of Liu Jin, a Ming dynasty eunuch, and Yuan Chonghuan, a Ming dynasty general. In 1542, lingchi was inflicted on a group of palace women who had attempted to assassinate the Jiajing Emperor. The bodies of the women were then displayed in public.[45][failed verification] Reports from Qing dynasty jurists such as Shen Jiaben show that executioners' customs varied, as the regular way to perform this penalty was not specified in detail in the penal code.[citation needed] Lingchi was also known in Vietnam, notably being used as the method of execution of the French missionary Joseph Marchand, in 1835, as part of the repression following the unsuccessful Lê Văn Khôi revolt. An 1858 account by Harper's Weekly claimed the martyr Auguste Chapdelaine was also killed by lingchi but in China; in reality he was beaten to death. As Western countries moved to abolish similar punishments, some Westerners began to focus attention on the methods of execution used in China. As early as 1866, the time when Britain itself moved to abolish the practise of hanging, drawing, and quartering from the British legal system, Thomas Francis Wade, then serving with the British diplomatic mission in China, unsuccessfully urged the abolition of lingchi.[citation needed] Lingchi remained in the Qing dynasty's code of laws for persons convicted of high treason and other serious crimes, but the punishment was abolished as a result of the 1905 revision of the Chinese penal code by Shen Jiaben.[46][47][48] |

歴史 この節は一次資料への言及に過度に依存している。この節を改善するために、二次資料または三次資料を追加してほしい。 (2024年9月) (このメッセージの削除方法とタイミングについては、こちらをご覧ください)  1835年、ベトナムにおけるジョセフ・マーチャンドの処刑 最も初期の皇帝の時代にも凌遅刑は存在したが、[要出典] それよりも残酷ではない同様の拷問が代わりに規定されることが多かった。秦の始皇帝の治世下では、秦王朝の第2代皇帝のもとで、様々な拷問が役人を処罰す るために用いられた。[32][33] 気まぐれで残酷かつ短命だった劉子耶は、無実の役人を凌遅刑で殺すことが多かった。[34] 高陽は、この方法で6人しか殺さなかった 、[35] 安史の乱では1人だけが処刑された。[36][37] 凌遅は五代時代(907年-960年)に知られていたが、最も早い時期にこの刑を廃止したのは史敬唐であった。[38] 他の支配者たちは引き続きこの刑を用いた。 この方法は遼の法律で規定され[39]、時折使用されていた[40]。天佐帝は在位中、この方法でしばしば処刑した[41]。 凌遅を廃止する別の初期の提案は、南宋の朝廷に提出された陸游(1125年-1210年)の覚書によるものである。呂氏はそこで「肉の筋肉がすでに取られ ても、生命の息はまだ絶たれておらず、肝臓と心臓はまだつながっており、視覚と聴覚もまだ存在している。それは自然の調和を乱し、仁政に有害であり、賢人 の時代にはふさわしくない」と述べた。[42] 呂氏のリンチの廃止を求める綿密な論拠は、代々の学者たちによって忠実に書き写され、伝えられた 清の時代後期に改革派の沈葆楨(1840~1913)が1905年の覚書にリンチ廃止を盛り込むまで、その中には各王朝の有力な法学者も含まれていた。こ の凌遅に対する反対の動きは、唐の時代に「残虐で異常な」刑罰(晒し首など)に反対する一般的な態度と一致しており、それは犯罪に対する合法的な刑罰の方 法を定義した五刑表に含まれていなかった。したがって、廃止の動きは西洋の影響から純粋に派生したものではなく、中国の法の伝統に深く根付いている。 後世の皇帝の下では、凌遅は最も悪質な犯罪、例えば反逆罪([43][44])のみに適用された。反逆罪はしばしば疑わしいか、あるいは偽りの罪状であ り、明の宦官である劉進や明の将軍である袁崇煥の死がその例である。1542年には、嘉靖帝を暗殺しようとした宮廷の女性たちに対して凌遅刑が執行され た。彼女たちの遺体はその後、公開された。[45][verification needed] 刑罰法典でこの刑罰の通常の執行方法が詳細に規定されていなかったため、沈寿恆などの清代の法学者による報告書では、執行人の慣習は様々であったことが示 されている。[citation needed] 凌遅刑はベトナムでも知られており、特に1835年にレ・ヴァン・コイの反乱鎮圧の一環として、フランス人宣教師ジョセフ・マーシャンが処刑された方法と して知られている。1858年の『ハーパーズ・ウィークリー』の記事では、殉教者オーギュスト・シャプドレーヌも中国で凌遅刑により処刑されたと主張して いるが、実際には彼は殴り殺された。 欧米諸国が同様の処罰の廃止に動く中、一部の欧米人は中国で用いられている処刑方法に注目するようになった。1866年には、英国自体が絞首刑、引きずり 回し刑、四分五体刑を英国の法制度から廃止する動きを見せたが、当時中国に駐在していた英国外交団のトーマス・フランシス・ウェイドは、リンチの廃止を訴 えたが、成功しなかった。 。凌遅は清王朝の法律では大逆罪やその他の重大な犯罪を犯した者に対する刑罰として残っていたが、1905年の沈葆楨による中国刑法改正により廃止され た。[46][47][48] |

| People put to death by lingchi Ming dynasty Fang Xiaoru (方孝孺): trusted bureaucrat of the Hanlin Academy relied upon by the Jianwen Emperor, put to death by lingchi in 1402 outside of Nanjing's Jubao Gate due to his refusal to draft an edict confirming the ascendance of the Yongle Emperor to the throne. He was forced to witness the brutal, special ten familial exterminations, the only one in history, where his family, friends and students were all executed, before he himself was killed. Cao Jixiang [zh] (曹吉祥): important eunuch serving under Emperor Yingzong of Ming, put to death by lingchi in 1461 for leading an army in rebellion. Sang Chong (桑沖): put to death by lingchi during the reign of the Chenghua Emperor for the rape of 182 women. Zheng Wang (郑旺): peasant from Beijing, put to death by lingchi in 1506 for claiming that the newly enthroned Zhengde Emperor's birth mother was not Empress Zhang (Hongzhi), but Zheng Jinlian, Zheng Wang's daughter, causing massive controversy. Liu Jin (劉瑾): important eunuch serving under the Zhengde Emperor, put to death by lingchi in 1510 for arrogating power. Legend has it that the punishment was carried out across 3 days, with 3300 slices in total. It was reported that when Liu Jin returned to prison after the first day, he continued to eat white porridge. After the punishment was completed, the people of Beijing, especially those persecuted under Liu Jin and their families, haggled for pieces of his flesh for a wen, and ate them with wine, to vent their anger. Palace plot of Renyin year: the 16 palace maids involved, including Yang Jinying and Huang Yulian, along with Imperial Concubine Wang Ning and Consort Duan were all put to death by lingchi in 1542 for the attempted assassination of the Jiajing Emperor. Wang Gao (王杲): a Jianzhou Jurchen awarded a position of command in Jianzhou. He was put to death by lingchi at Beijing in 1575 due to repeated raids into Ming border territories. He is said to be Nurhaci's maternal great-grandfather or maternal grandfather. Zheng Man (鄭鄤): a shujishi during the reign of the Chongzhen Emperor, who was defamed by Chief Grand Secretary Wen Tiren and charged with the crimes of "causing his mother to be caned (due to fuji), and raping his younger sister and daughter-in-law". Executed by lingchi in 1636. Yuan Chonghuan (袁崇煥): famous general during the reign of the Chongzhen Emperor, entrusted with defence against the Jurchens. The Emperor reportedly fell for the Jurchens' stratagem of sowing discord, and sentenced him to death by lingchi for the crime of attempting to rebel with the help of the Jurchens. It is said that the people of Beijing, not knowing of Yuan's innocence, fought to eat pieces of his flesh. Qing dynasty Geng Jingzhong (耿精忠): one of the rulers of the Three Feudatories during the reign of the Kangxi Emperor. He was put to death by lingchi after their revolt failed. He Luohui (何洛會) and Hu Ci (胡錫): put to death by lingchi due to their earlier defamation of Hooge, Prince Su. Zhu Yigui (朱一貴): duck farmer in Taiwan during the reign of the Kangxi Emperor. Unhappy with the local governor's indulgence of his son's excesses, he revolted to re-establish the Ming dynasty by claiming to be a descendant of the Hongwu Emperor. After the revolt failed, he was transported to Beijing and put to death by lingchi. On 1 November 1728, after the Qing reconquest of Lhasa in Tibet, several Tibetan rebels were sliced to death by Qing Manchu officers and officials in front of the Potala Palace. Qing Manchu President of the Board of Civil Office, Jalangga, Mongol sub-chancellor Sen-ge and brigadier-general Manchu Mala ordered Tibetan rebels Lum-pa-nas and Na-p'od-pa to be sliced.[49][50] Tibetan rNam-rgyal-grva-ts'an college administrator (gner-adsin) and sKyor'lun Lama were tied together with Lum-pa-nas and Na-p'od-pa on four scaffolds (k'rims-sin) to be sliced. The Manchus used musket matchlocks to fire three salvoes and then the Manchus strangled the two lamas while slicing Lum-pa-nas and Na-p'od-pa to death. The Tibetan population was depressed by the scene and the writer of MBTJ continued to feel sad as he described it 5 years later. The public execution spectacle worked on the Tibetans since they were "cowed into submission" by the Qing. Even the Tibetan collaborator with the Qing, Polhané Sönam Topgyé (P'o-lha-nas), felt sad at his fellow Tibetans being executed in this manner and prayed for them. All of this was included in a report sent to the Qing Yongzheng Emperor.[51] On 23 January 1751 (25/XII), Tibetan rebels who participated in the Lhasa riot of 1750 against the Qing were sliced to death by Qing Manchu general Bandi, similar to what happened on 1 November 1728. 6 Tibetan rebel leaders plus Tibetan rebel leader Blo-bzan-bkra-sis were sliced to death.[52] Manchu General Bandi sent a report to the Qing Qianlong emperor on 26 January 1751 on how he carried out the slicing of the Tibetan rebels: dBan-rgyas (Wang-chieh), Padma-sku-rje-c'os-a['el (Pa-t'e-ma-ku-erh-chi-ch'un-p'i-lo) and Tarqan Yasor (Ta-erh-han Ya-hsün) were sliced to death for injuring the Manchu ambans with arrows, bows and fowling pieces during the Lhasa riot when they assaulted the building the Manchu ambans (Labdon and Fucin) were in; Sacan Hasiha (Ch'e-ch'en-ha-shih-ha) for murder of multiple individuals; Ch'ui-mu-cha-t'e and Rab-brtan (A-la-pu-tan) for looting money and setting fire during the attack on the Ambans; Blo-bzan-bkra-sis, the mgron-gner[clarification needed] for being the overall leader of the rebels who led the attack which looted money and killed the Manchu ambans.[53] Eledeng'e (額爾登額) or possibly 額爾景額): The Qianlong emperor ordered Manchu general Eledeng'e (also spelled E'erdeng'e 額爾登額) to be sliced to death after his commander Mingrui was defeated at the Battle of Maymyo in the Sino-Burmese War in 1768 because Eledeng'i was not able to help flank Mingrui when he did not arrive at a rendezvous.[54] Chen De (陈德): a retrenched chef during the reign of the Jiaqing Emperor. Put to death by lingchi in 1803 for a failed assassination of the emperor outside the Forbidden City. Zhang Liangbi (张良璧): a pedophile during the reign of the Jiaqing Emperor. He was 70 years old when caught. He was put to death by lingchi in 1811 for raping 16 underage girls, resulting in the deaths of 11 of them. Pan Zhaoxiang (潘兆祥): poisoned his father. Put to death by lingchi on 24 June in the fifth year of the reign of the Daoguang Emperor (1825). Jahangir Khoja (張格爾): a Uyghur Muslim Sayyid and Naqshbandi Sufi rebel of the Afaqi suborder, Jahangir Khoja was sliced to death in 1828 by the Manchus for leading a rebellion against the Qing. Li Shangfa (李尚發): slashed his mother to death in a fit of hysteria. Put to death by lingchi in May of the 25th year of the reign of the Daoguang Emperor (1845). Three bystanders were sentenced to 100 strokes of the cane each for not moving to stop him. Shi Dakai (石達開): the most decorated general of the Taiping Heavenly Kingdom, proclaimed as the Wing King. He was trapped during a crossing of the Dadu River due to a sudden flood, and surrendered to Qing forces to save his army. He was put to death by lingchi together with his immediate subordinates. He chided his subordinates for crying in pain during their ordeal, and he himself said not a word during his turn. Hong Tianguifu (洪天貴福): son of the Heavenly King Hong Xiuquan of the Taiping Heavenly Kingdom. He was captured by famous general Shen Baozhen and put to death by lingchi. He was possibly the youngest to ever have been subjected to lingchi, at 14 years old. Lin Fengxiang (林鳳祥): general of the Taiping Heavenly Kingdom. Put to death by lingchi in March 1855 at the Beijing Caishikou Execution Grounds. Reportedly, the process was recorded. Kumud Pazik (古穆·巴力克): a chief of the Sakizaya people in Hualien County, Taiwan. He allied with the Kavalan people in armed rebellion against the Qing's expansionist policies against the Taiwanese indigenous peoples (a result of the Japanese invasion of Taiwan in 1874). He was publicly put to death by lingchi on 9 September 1878 as a warning to the various villages in the aftermath of the Karewan Incident. Kang Xiaoba (康小八): a bandit who robbed and killed countless innocents, armed with a gun stolen from Westerners. He caused disturbances in Beijing, managing to scare Empress Dowager Cixi, before he was caught and put to death by lingchi. Wang Weiqin (王維勤): an influential landowner in his village in Shandong who masterminded the killings of a rival family of twelve. He was put to death by lingchi in October 1904. He rode a chariot to the execution grounds, so he was suspected to have much influence. French soldiers took photos of the execution, and it is believed that this is the first time photographs of lingchi spread overseas. Fujuri (富珠哩): a Mongol prince's slave, who reportedly rebelled against said prince because the prince tried to force himself upon Fujuri's wife. He was put to death by lingchi on 10 April 1905. Lingchi was abolished as a punishment two weeks later, due to pressure by Westerners, in part because French soldiers took clear photos of Fujuri's execution. Xu Xilin (徐錫麟): a member of the Guangfuhui; put to death by lingchi on 6 July 1907. Republican era Ling Fushun (凌福顺): soldier of the Chinese Communist Party, who was caught at Puyuanzhen in Zhouning County after returning from soliciting donations in Jian'ou. He was put to death by lingchi by Republican forces on 25 April 1936. Published accounts Sir Henry Norman, The People and Politics of the Far East (1895). Norman was a Liberal British Parliamentarian and government minister whose collection is now owned by the University of Cambridge. Norman gives an eyewitness account of various physical punishments and tortures inflicted in a magistrate's court (yamen) and of the execution by beheading of 15 men. He gives the following graphic account of a lingchi execution but does not claim to have witnessed such an execution himself. "[The executioner] grasping handfuls from the fleshy parts of the body such as the thighs and breasts slices them away ... the limbs are cut off piecemeal at the wrists and ankles, the elbows and knees, shoulders and hips. Finally the condemned is stabbed to the heart and the head is cut off."[55] George Ernest Morrison, An Australian in China (1895) differs from some other reports in stating that most lingchi mutilations are in fact made postmortem. Morrison wrote his description based on an account related by a claimed eyewitness: "The prisoner is tied to a rude cross: he is invariably deeply under the influence of opium. The executioner, standing before him, with a sharp sword makes two quick incisions above the eyebrows, and draws down the portion of skin over each eye, then he makes two more quick incisions across the breast, and in the next moment he pierces the heart, and death is instantaneous. Then he cuts the body in pieces; and the degradation consists in the fragmentary shape in which the prisoner has to appear in heaven."[56] The Times (9 December 1927), a journalist reported from Canton that the Communists were targeting Christian priests and that "It was announced that Father Wong was to be publicly executed by the slicing process." George de Roerich, Trails to Inmost Asia (1931), p . 119, relates the story of the assassination of Yang Tseng-hsin, Governor of Sinkiang in July 1928, by the bodyguard of his foreign minister Fan Yao-han. Fan was seized, and he and his daughter were both executed by lingchi, the minister forced to watch his daughter's execution first. Roerich was not an eyewitness to this event, having already returned to India by the date of the execution. George Ryley Scott in History of Torture (1940) claims that many were executed this way by the Chinese Communist insurgents; he cites claims made by the Nanking government in 1927. It is likely that these claims were anti-communist propaganda. Scott also uses the term "the slicing process" and differentiates between the different types of execution in different parts of the country. There is no mention of opium. Riley's book contains a picture of a sliced corpse (with no mark to the heart) that was killed in Guangzhou (Canton) in 1927. It gives no indication of whether the slicing was done post-mortem. Scott claims it was common for the relatives of the condemned to bribe the executioner to kill the condemned before the slicing procedure began. |

凌遅刑に処された人々 明朝 方孝孺(Fang Xiaoru):建文帝の信任厚い翰林院の重臣であったが、永楽帝の皇位継承を認める詔書の起草を拒否したため、1402年に南京聚宝門外で凌遅刑に処さ れた。彼は、一族全員が処刑されるという歴史上唯一の残虐な特別十族滅門の刑を目の当たりにさせられ、その後、殺された。 曹吉祥(曹吉祥):明の英宗に仕えた重要な宦官。1461年に反乱軍を率いた罪で凌遅刑に処された。 桑沖(Sang Chong):成化帝の治世下で、182人の女性に対するレイプ容疑により凌遅刑に処された。 鄭旺(Zheng Wang):北京の農民。1506年に、即位したばかりの正徳帝の実母は張皇后(弘治帝)ではなく、鄭旺の娘である鄭金蓮であると主張し、大論争を引き起こしたため、凌遅刑に処された。 劉瑾(りゅうきん):正徳帝に仕えた重要な宦官。1510年に権力を簒奪したとして凌遅刑に処された。伝説によると、処刑は3日間かけて行われ、合計 3300回切られたという。劉瑾が一日目を終えて牢に戻ったとき、彼は白い粥を食べ続けたという。処刑が完了した後、北京の人々、特に劉瑾とその家族に迫 害された人々は、彼の肉片を物々交換で手に入れ、酒と一緒に食べ、怒りをぶつけた。 Renyin年宮廷陰謀:楊金英、黄爾姍ら16人の宮女、王寧妃、段氏貴妃ら16人が嘉靖帝の暗殺未遂事件に関与したとして、1542年に凌遅刑に処されて死亡した。 王杲(おうこう):建州の女真人で、建州の指揮官に任命された。1575年に明の国境地域への度重なる襲撃により、北京で凌遅刑に処された。ヌルハチの母方の曽祖父または祖父であると言われている。 鄭鄤(Zheng Man):崇禎帝の時代に仕官した秀才。文震旦(Wen Tiren)大司礼に讒言され、「母に鞭打ち刑を受けさせた(宦官のせいで)、妹と義理の娘を強姦した」罪で告発された。1636年に凌遅刑に処された。 袁崇煥(Yuan Chonghuan):崇禎帝の時代に活躍した名将で、女真族の防衛を任されていた。皇帝は女真族の不和を煽る策略にまんまと引っかかり、女真族の力を借 りて反乱を企てた罪で、凌遅刑による死刑を宣告したと伝えられている。北京市民は、袁が無実であることを知らず、彼の肉片を奪い合って食べたと言われてい る。 清の時代 耿精忠(Geng Jingzhong):康熙帝の時代に三藩の乱を起こした指導者の一人。 反乱が失敗した後、凌遅刑に処された。 何洛会(He Luohui)と胡錫(Hu Ci):以前に蘇王・豪格を誹謗したため、凌遅刑に処された。 朱一貴(Zhu Yigui):康熙帝の時代に台湾でアヒルを飼育していた農民。地方総督が自分の息子の横暴を許していることに不満を抱き、洪武帝の末裔であると称して明朝再興を掲げて反乱を起こした。反乱が失敗した後、北京に移送され、凌遅刑に処された。 1728年11月1日、清によるチベットのラサ再征服の後、ポタラ宮殿の前で、清の満州人将校や役人によって数人のチベット人反乱者が斬首された。清国満 州人の内務府理事ジャランガ、モンゴル人副宰相センゲ、満州人准将マラーは、チベット人反乱軍のルンパナスとナポドパを斬首するように命じた。[49] [50] チベット人 -rgyal-grva-ts'an大学の管理者(gner-adsin)とsKyor'lunラマ僧は、4つの足場(k'rims-sin)にLum- pa-nasとNa-p'od-paと共に縛り付けられ、切り殺された。満州人はマスケット銃の散弾を3発発射し、その後、満州人は2人のラマ僧の首を絞 めながら、ルンパ・ナスとナポド・パを切り刻んで殺した。この光景にチベット人は打ちのめされ、MBTJの著者は5年後もその様子を悲しく思い出した。公 開処刑の光景は、清国に「服従を強いられた」チベット人には効果的だった。清と協力関係にあったチベット人、ポルハネ・ソンアム・トプジェ(P'o- lha-nas)でさえ、同胞がこのような形で処刑されるのを悲しく思い、彼らのために祈った。これらのすべてが、清の雍正帝に送られた報告書に記載され た。[51] 1751年1月23日(1750年12月25日)、1750年のラサでの清に対する暴動に参加したチベット人反乱軍は、1728年11月1日に起こったこ とと同様に、清の満州人将軍バンドゥによって斬首された。6人のチベット人反乱軍の指導者とチベット人反乱軍の指導者ブロ・ブザン・ブクラ・シスが斬首さ れた。[52] 満州人将軍バンドイは、1751年1月26日に、チベット人反乱軍の斬首をどのように行ったかについて、清の乾隆帝に報告を送った。ダン・ルギャス(ワ ン・チエ)、パドマ・スク・ジェ・チョス・アエル(パ・テマ・ ラサの暴動の際に、満州人アンバンの建物に襲撃をかけた際に、矢や弓、鳥撃ち用の銃で満州人アンバンを負傷させた罪で、ダンギャス(ワンチエ)、パドマス クジェチョスパエラエル(パテマクーエルチーチュンピロ)、タルカンヤソル(ターレンハンヤスン)は斬首された。サカンハシハ(チェチェンハシ)は 複数の殺人罪でサカン・ハシハ(Ch'e-ch'en-ha-shih-ha)、アンバン襲撃時の金銭略奪と放火の罪でチュイムチャテとラブブタン(A- la-pu-tan)、アンバン襲撃時の金銭略奪と殺人の罪で反乱軍の総指揮官であるブロブザンブクラシス(Blo-bzan-bkra-sis)、 mgron-gner[要出典]、 額爾登額(Eledeng'e)または額爾景額(額爾景額): 乾隆帝は、1768年の清緬戦争におけるメイミョーの戦いで、マンジュ人の将軍エレンデンゲ(額爾登額とも表記される)が、待ち合わせ場所に現れなかった ミングリを助けられなかったため、ミングリが敗北した後にエレンデンゲを斬首するように命じた。 陳徳(Chen De):嘉慶帝の治世下で左遷された料理人。1803年に紫禁城の外で皇帝暗殺に失敗した罪で凌遅刑に処された。 張良璧(Zhang Liangbi):嘉慶帝の治世下で小児性愛者であった。逮捕時は70歳であった。1811年に16人の未成年の少女を強姦し、うち11人の死に至らしめた罪で凌遅刑に処された。 潘兆祥(Pan Zhaoxiang):父親に毒を盛った。道光帝の治世5年目(1825年)6月24日、凌遅刑により処刑された。 ジャハンギール・ホージャ(張格爾):ウイグル人イスラム教シーア派のサイイドであり、ナクシュバンディー・スーフィーの反乱者であったジャハンギール・ホージャは、清に対する反乱を主導したとして、1828年に満州人により斬首された。 李尚発(Li Shangfa):ヒステリーに陥り、母親を斬り殺した。道光帝の25年目の5月(1845年)に凌遅刑に処された。傍観者3名が彼を止めに入らなかったとして、それぞれ100回の鞭打ち刑に処された。 石達開(Shi Dakai):太平天国の最も勇敢な将軍であり、翼王と称された。彼は大渡河を渡る際に突然の洪水に遭い、軍を救うために清軍に降伏した。彼は直属の部下 とともに凌遅刑に処された。彼は部下たちが拷問中に泣くのをたしなめ、自身は拷問中に一言も発しなかった。 洪天貴福(ホン・ティエンクイフ):太平天国の天王洪秀全の息子。名将沈葆楨に捕らえられ、凌遅刑に処された。14歳という最年少で凌遅刑に処された可能性がある。 林鳳祥(リン・フォンシャン):太平天国の将軍。1855年3月、北京菜市口刑場で凌遅刑に処された。その様子は記録されたとされる。 古穆·巴力克(Kumud Pazik):台湾花蓮県のサキザヤ族の族長。彼は、台湾先住民に対する清国の拡張政策(1874年の日本による台湾侵攻の結果)に反対して、クヴァラン 族と武装蜂起した。彼は、1878年9月9日に凌遅刑により公開処刑された。これは、カラワン事件の余波で、各村落に警告を与えるためであった。 康小八(Kang Xiaoba):西洋人から盗んだ銃で武装し、無実の人々を数え切れないほど襲撃し殺害した盗賊。彼は北京で騒乱を起こし、西太后を脅かすことに成功したが、その後捕らえられ、凌遅刑により処刑された。 王維勤(Wang Weiqin):山東省の村で有力な地主であり、ライバル一族12人の殺害を主導した。1904年10月に凌遅刑に処された。処刑場まで馬車で移動したた め、大きな影響力を持っていたと推測される。フランス人兵士が処刑の様子を写真に収め、これが初めて海外に広まった凌遅刑の写真であると考えられている。 富珠哩(フジュリー):モンゴル王族の奴隷で、王族が富珠哩の妻に無理やり迫ったため、富珠哩が王族に反旗を翻したと伝えられている。1905年4月10 日、凌遅刑に処された。フランス兵士が鮮明な写真を撮影したこともあり、西洋人の圧力により、2週間後に凌遅刑は廃止された。 徐錫麟(Xu Xilin):広福会のメンバー。1907年7月6日凌遅刑により処刑。 共和 凌福順(Ling Fushun):中国共産党の兵士。建溝で募金活動を行った後、鄒寧県の溝沿鎮で捕らえられた。1936年4月25日、共和党軍により凌遅刑に処された。 出版された記録 サー・ヘンリー・ノーマン著『極東の人々と政治』(1895年) ノーマンは英国議会自由党の議員であり、政府の大臣でもあった。彼のコレクションは現在ケンブリッジ大学が所有している。ノーマンは、裁判所(衙門)で科 せられたさまざまな肉刑や拷問、および15人の男性に対する斬首刑の目撃証言を述べている。彼はリンチの処刑について以下のような生々しい描写をしている が、自身がそのような処刑を目撃したとは主張していない。「(処刑人は)太ももや胸など、肉付きの良い部分から手でつかめる分を切り落とす。手足は手首と 足首、肘と膝、肩と腰の部分で、バラバラに切り落とされる。最後に死刑囚は心臓を刺され、首を切られる」[55] ジョージ・アーネスト・モリソン著『中国にいたオーストラリア人』(1895年)は、リンチのほとんどは実際には死後に行われると述べている点で、他のい くつかの報告とは異なる。モリソンは、自称目撃者の証言に基づいて記述している。「囚人は粗野な十字架に縛り付けられる。彼は常にアヘンの強い影響下にあ る。死刑執行人は囚人の前に立ち、鋭い刀で眉の上を素早く2回切り込み、両目の上の皮膚を引き下げる。それから胸を横に素早く2回切り込み、次の瞬間、心 臓を突き刺し、即死させる。そして死体を切り刻む。この屈辱的な処刑は、囚人が天国で断片的な姿で現れなければならないというものである。」[56] タイムズ紙(1927年12月9日付)は、広州からの特派員による記事で、共産党がキリスト教の司祭を標的にしていると報じ、「ウォン神父が公開処刑されることが発表された」と伝えている。 ジョージ・ド・ロリッシュ著『アジアの奥地への道』(1931年)119ページには、 119ページでは、1928年7月に新疆省の省長であった楊騰新が、外務大臣の范瑶漢の護衛官によって暗殺されたという話を紹介している。 范は拘束され、彼と彼の娘はともに凌遅刑に処された。 娘の処刑を大臣はまず見せられた。 ロエリッヒは処刑の日までにすでにインドに戻っていたため、この事件の目撃者ではなかった。 ジョージ・ライリー・スコットは著書『拷問の歴史』(1940年)の中で、中国共産党の反乱分子によって多くの人がこの方法で処刑されたと主張している。 彼は1927年の南京政府の主張を引用している。これらの主張は反共産主義のプロパガンダであった可能性が高い。スコットは「切り刻むプロセス」という用 語も使用しており、中国国内の異なる地域における異なる処刑方法を区別している。アヘンについては言及されていない。ライリーの著書には、1927年に広 州(カントン)で処刑された切り刻まれた死体(心臓に傷跡がない)の写真が掲載されている。この写真から、切り刻む処置が死後に行われたのかどうかはわか らない。スコットは、死刑囚の親族が死刑執行人に賄賂を贈り、切り刻む処置が始まる前に死刑囚を殺すことが一般的であったと主張している。 |

Photographs Lingchi execution in Beijing c. April 1905, apparently of Fou-Tchou-Li The first Western photographs of lingchi were taken in 1890 by William Arthur Curtis of Kentucky in Canton.[57] French soldiers stationed in Beijing had the opportunity to photograph three different lingchi executions in 1904 and 1905:[58] Wang Weiqin (王維勤), a former official who killed two families, executed on 31 October 1904.[59][60] Unknown, reason unknown, possibly a young deranged boy who killed his mother, and was executed in January 1905. Photographs were published in various volumes of Georges Dumas' Nouveau traité de psychologie, 8 vols., Paris, 1930–1943, and again nominally by Bataille (in fact by Lo Duca), who mistakenly appended abstracts of Fou-tchou-li's executions as related by Carpeaux (see below).[61] Fou-tchou-li or Fuzhuli (符珠哩),[62] a Mongol guard who killed his master, the Prince of the Aohan Banner of Inner Mongolia, and who was executed on 10 April 1905; as lingchi was to be abolished two weeks later, this was presumably the last attested case of lingchi in Chinese history,[62] or said Kang Xiaoba (康小八)[63] Photographs appeared in books by Matignon (1910), and Carpeaux (1913), the latter claiming (falsely) that he was present.[citation needed] Carpeaux's narrative was mistakenly, but persistently, associated with photographs published by Dumas and Bataille. Even related to the correct set of photos, Carpeaux's narrative is highly dubious; for instance, an examination of the Chinese judicial archives shows that Carpeaux bluntly invented the execution decree. The proclamation is reported to state: "The Mongolian princes demand that the aforesaid Fou-Tchou-Le, guilty of the murder of Prince Ao-Han-Ouan, be burned alive, but the Emperor finds this torture too cruel and condemns Fou-Tchou-Li to slow death by leng-tch-e (different spelling of lingchi, cutting into pieces)."[64] |

写真 1905年4月頃の北京における凌遅刑の様子、おそらく傅采漣(Fou-Tchou-Li) 西洋人が撮影した最初の凌遅刑の写真は、1890年にケンタッキー州出身のウィリアム・アーサー・カーティス(William Arthur Curtis)が広州で撮影したものである。 北京に駐留していたフランス兵は、1904年と1905年に3つの異なる凌遅刑の執行の様子を撮影する機会があった。 王維勤(Wang Weiqin)は、2つの家族を殺害した元役人で、1904年10月31日に処刑された。[59][60] 不明、理由は不明、おそらくは母親を殺害した精神異常の少年で、1905年1月に処刑された。写真はジョルジュ・デュマの『新心理学講義』全8巻(パリ、 1930年~1943年)のさまざまな巻に掲載され、また、バタイユ(実際にはロ・ドゥーカ)によって名目上、再度掲載された。バタイユはカルポーが伝え たフー・チューリの処刑の概要を誤って添付した(下記参照)。[61] フー・チョー・リーまたはフーチョリー(符珠哩)は、[62] 1905年4月10日に処刑された、主人である内モンゴル旗の王子を殺害したモンゴル人の護衛兵である。凌遅刑は2週間後に廃止されることになっていたた め、これは中国史上で記録に残る最後の凌遅刑の事例であると考えられる。[ 62] または康小八(カン・シャオバ)[63] マティニョン(1910年)とカルポー(1913年)の著書に写真が掲載された。後者は、彼がその場に居合わせた(誤って)と主張している。[要出典] カルポーの証言は、デュマとバタイユが出版した写真と誤って、しかし根強く関連付けられている。正しい写真群と関連付けられたとしても、カルポーの証言は 極めて疑わしい。例えば、中国の司法記録の調査では、カルポーが処刑令をでっちあげたことが明らかになっている。布告には次のように書かれていると報告さ れている。「モンゴルの王子たちは、アオ・ハン・オアン王子殺害の罪で、前述のフー・チュウ・リーを生きながら焼くことを要求したが、皇帝はこれをあまり にも残酷な拷問とみなし、フー・チュウ・リーをレンチー(リンチの異なるスペル)による長時間の死に値すると宣告した」[64] |

| Popular culture Accounts of lingchi or the extant photographs have inspired or referenced in numerous artistic, literary, and cinematic media: Nonfiction Susan Sontag mentions the 1905 case in Regarding the Pain of Others (2003). One reviewer wrote that though Sontag includes no photographs in her book – a volume about photography – "she does tantalisingly describe a photograph that obsessed the philosopher Georges Bataille, in which a Chinese criminal, while being chopped up and slowly flayed by executioners, rolls his eyes heavenwards in transcendent bliss."[65] Bataille wrote about lingchi in L'expérience intérieure (1943) and in Le coupable (1944). He included five pictures in his The Tears of Eros (1961; translated into English and published by City Lights in 1989).[66] Music Naked City's album Leng Tch'e is about this form of torture. The tenth song on Taylor Swift's seventh album, Lover, is entitled "Death By A Thousand Cuts" and compares the singer's heartbreak to this punishment. Literature The "death by a thousand cuts" with reference to China is mentioned in Amy Tan's novel The Joy Luck Club, and Robert van Gulik's Judge Dee novels. The 1905 photos are mentioned in Thomas Harris' novel Hannibal,[67] in Julio Cortázar's novel Hopscotch and are also a central topic in Salvador Elizondo's Farabeuf, where the procedure is carried out by the protagonist. Agustina Bazterrica mentioned the torture in her book Tender is the Flesh, as the method used by the sister of the protagonist to make the meat served at the memorial party fresh and tasty. The Chinese idiom "千刀萬剮" qiāndāo wànguǎ is also a reference to linchi. Film A scene of Lingchi appeared in the 1966 film The Sand Pebbles. Inspired by the 1905 photos, Chinese artist Chen Chieh-jen created a 25-minute, 2002 video called Lingchi – Echoes of a Historical Photograph, which has generated some controversy.[68] The 2007 film The Warlords, which is loosely based on historical events during the Taiping Rebellion, ended with one of its main characters executed by Lingchi. Lingchi is shown as a method of execution in the 2014 TV series The 100. Lingchi was portrayed in the 2015 TV series Jessica Jones[citation needed]. |

大衆文化 リンチの記録や現存する写真の数々は、数多くの芸術、文学、映画などのメディアにインスピレーションを与えたり、参照されたりしている。 ノンフィクション スーザン・ソンタグは『他者の苦痛について』(2003年)の中で、1905年の事件について言及している。ある批評家は、ソントンが写真に関する著作で あるこの本に写真を一切掲載していないにもかかわらず、「哲学者ジョルジュ・バタイユを夢中にさせた写真について、非常に魅力的に描写している。その写真 には、処刑人によって切り刻まれ、ゆっくりと皮を剥がれる中国人犯罪者が、超越的な至福感に包まれて天を仰ぐ姿が写っている」と書いている。[65] バタイユは『内面の体験』(1943年)と『罪人』(1944年)で凌遅刑について書いている。彼は『エロスの涙』(1961年、1989年に英訳されシ ティライツ社より出版)に5枚の写真を掲載した。[66] 音楽 裸のシティのアルバム『Leng Tch'e』は、この拷問の形式について歌っている。テイラー・スウィフトの7枚目のアルバム『Lover』の10曲目は「Death By A Thousand Cuts」というタイトルで、この処罰に歌手の失恋を例えている。 文学 中国を題材にした「千の切り傷による死」は、エイミー・タンの小説『ジョイ・ラック・クラブ』やロバート・ヴァン・グリックの小説『判官ディー』にも登場 する。1905年の写真は、トマス・ハリスの小説『ハンニバル』[67]やフリオ・コルタサルの小説『ホップスコッチ』にも登場し、また、サルバドール・ エリゾンドの小説『ファラブーフ』では、この処置が主人公によって実行されるという、中心的なテーマとなっている。アグスティナ・バステリカーは著書 『Tender is the Flesh』の中で、主人公の姉が追悼パーティーで供される肉を新鮮で美味しくするために用いた方法として、この拷問について言及している。中国のことわ ざ「千刀万剮」(qiāndāo wànguǎ)もリンチを指す。 映画 リンチの場面は、1966年の映画『The Sand Pebbles』にも登場している。1905年の写真に触発された中国のアーティスト、陳界仁(Chen Chieh-jen)は、2002年のビデオ作品『凌遅刑 - 歴史的写真の残響』という25分の作品を制作し、物議を醸した。[68] 2007年の映画『ウォーロード』は、太平天国の乱の間の歴史的事件を大まかに基にしており、その映画は、主要人物の一人が凌遅刑で処刑される場面で終 わっている。リンチは、2014年のテレビシリーズ『The 100』でも処刑法として描かれている。リンチは、2015年のテレビシリーズ『ジェシカ・ジョーンズ』でも描かれている[要出典]。 |

| Death by a Thousand Cuts – a 2008 book that examines the practice of lingchi Flaying Hanged, drawn and quartered – an English method of torturous execution Scaphism – an alleged ancient Persian method of torturous execution Sinophobia Tameshigiri – in Japan, cuts for testing swords, sometimes used on people Waist chop – a form of execution in China, also noted for causing a lingering death Yellow Peril |

千切りによる死 - 2008年に出版された本で、凌遅刑について検証している 皮剥ぎ 絞首刑、引き裂き、四つ裂き - イングランドの拷問刑の方法 スカフィズム - 古代ペルシャの拷問刑の方法とされるもの シノフォビア 試し切り - 日本では刀の切れ味を試すために行う切りつけで、時に人間に対して行われることもある 腰斬り - 中国の処刑方法で、長時間の死をもたらすことでも知られる 黄禍 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lingchi |

☆

☆

☆