power

権力

power

★権力(power)とは、あらゆる意味での強制力のことであ る。権力を物理的諸力(=暴力)と区別してはならない。なぜなら、西洋 語の権力はすべて英語のパワーに他ならないからだ——もちろん政治権力(political power)という狭い言い方も存在する。このことは、ジャン=ジャック・ルソーの 『社会契約論』第1篇、第3章にある(→このページと類似の議論は「権力概念の考察」を参照)。

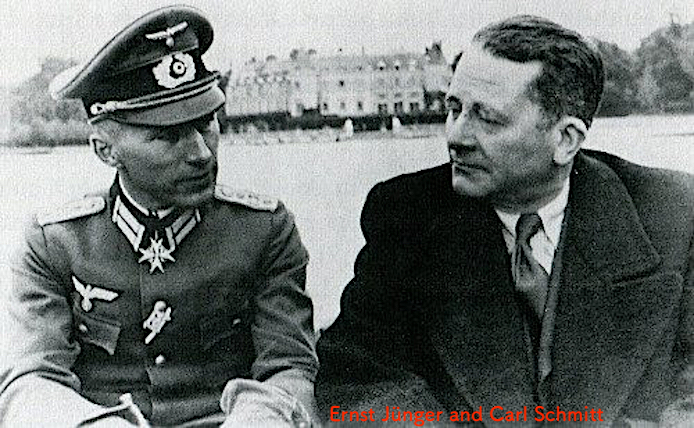

★カール・シュミットの権力:カール・シュミットは次のように簡潔にまとめる。「力は物理 的権力であるし、強盗の発射するピストルもまた権力である」(シュ ミット『政治神学』田中浩ら訳、26ページ)。

☆政治学において、権力[political power]とは、行為者の能 力、行動、信念、または行動を決定する効果の社会的生産である。権力は、ある行為者が別の行為者に対して行使する脅威や武力(強制)のみを指すのではな く、拡散した手段(制度など)を通じて行使されることもある。権力は、行為者同士の関係を秩序づける構造的な形態(例えば、主人と奴隷、家長とその親族、 雇用者とその従業員、親と子、政治代表とその有権者など)を取ることもあれば、カテゴリーや言語が特定の行動や集団に他のものよりも正当性を付与するよう な言説的な形態を取ることもある。 権威という用語は、社会構造によって正当であると認識されたり、社会的に承認されたりする権力に対してしばしば用いられる。権力は悪や不正と見なされるこ ともあるが、権力は善であり、また、他者を助け、動かし、力づけるような人文主義的な目的を遂行するために受け継がれたり与えられたりするものとも見なさ れる。 学者たちは、ソフトパワーとハードパワーの違いを区別している(→Political Power)。

☆コーネルに赴任したベネディクト・アンダーソンは、

廊下でアラン・ブルームが「古代ギリシア人は、プラトンやアリストテレスでも、現代人が親しんでいる『権力(パワー)』の概念を知らなかったんだ」という

話を立ち聞して、図書館で古代ギリシャ語の語彙を調べてみた。専制政治、民主主義、貴族政治君主制、都市、軍隊は見つけることができたが、抽象的、一般概

念としての権力を、アンダーソンはみつけることができなかった(アンダーソン 2009:162)。

政 治学における「権力」(Power (social and political))

| In

political science, power

is the social production of an effect that determines the capacities,

actions, beliefs, or conduct of actors.[1] Power does not exclusively

refer to the threat or use of force (coercion) by one actor against

another, but may also be exerted through diffuse means (such as

institutions).[2] Power may also take structural forms, as it orders actors in relation to one another (such as distinguishing between a master and an enslaved person, a householder and their relatives, an employer and their employees, a parent and a child, a political representative and their voters, etc.), and discursive forms, as categories and language may lend legitimacy to some behaviors and groups over others.[1] The term authority is often used for power that is perceived as legitimate or socially approved by the social structure. Power can be seen as evil or unjust; however, power can also be seen as good and as something inherited or given for exercising humanistic objectives that will help, move, and empower others as well. Scholars[3] have distinguished the differences between soft power and hard power. |

政治学において、権力とは、行為者の能力、行動、信念、または行動を決

定する効果の社会的生産である。[1]

権力は、ある行為者が別の行為者に対して行使する脅威や武力(強制)のみを指すのではなく、拡散した手段(制度など)を通じて行使されることもある。

[2] 権力は、行為者同士の関係を秩序づける構造的な形態(例えば、主人と奴隷、家長とその親族、雇用者とその従業員、親と子、政治代表とその有権者など)を取 ることもあれば、カテゴリーや言語が特定の行動や集団に他のものよりも正当性を付与するような言説的な形態を取ることもある。 権威という用語は、社会構造によって正当であると認識されたり、社会的に承認されたりする権力に対してしばしば用いられる。権力は悪や不正と見なされるこ ともあるが、権力は善であり、また、他者を助け、動かし、力づけるような人文主義的な目的を遂行するために受け継がれたり与えられたりするものとも見なさ れる。 学者たちは、ソフトパワーとハードパワーの違いを区別している。 |

| Theories Five bases of power Main article: French and Raven's five bases of power In a now-classic study (1959),[4] social psychologists John R. P. French and Bertram Raven developed a schema of sources of power by which to analyse how power plays work (or fail to work) in a specific relationship. According to French and Raven, power must be distinguished from influence in the following way: power is that state of affairs that holds in a given relationship, A-B, such that a given influence attempt by A over B makes A's desired change in B more likely. Conceived this way, power is fundamentally relative; it depends on the specific understandings A and B each apply to their relationship and requires B's recognition of a quality in A that would motivate B to change in the way A intends. A must draw on the 'base' or combination of bases of power appropriate to the relationship to effect the desired outcome. Drawing on the wrong power base can have unintended effects, including a reduction in A's own power. French and Raven argue that there are five significant categories of such qualities, while not excluding other minor categories. Further bases have since been adduced, in particular by Gareth Morgan in his 1986 book, Images of Organization.[5] |

理論 権力の5つの基盤 詳細は「フレンチとレーベンの権力の5つの基盤」を参照 古典的研究(1959年)において、[4] 社会心理学者のジョン・R・P・フレンチとバートラム・レーベンは、特定の人間関係において権力がどのように作用するのか(または作用しないのか)を分析 するための権力の源泉の図式を開発した。 フレンチとレーベンによると、権力は影響力とは次のように区別されなければならない。権力とは、AとBの関係において、AがBに対して特定の影響力を及ぼ そうとする試みによって、Aが望む変化がBにもたらされる可能性が高くなるような状態である。このように考えれば、権力は基本的に相対的なものであり、A とBがそれぞれの関係に適用する特定の理解に依存し、Aが意図する方法でBが変化する動機となるようなAの資質をBが認識することが必要となる。Aは望ま しい結果を達成するために、関係に適した「基盤」または複数の基盤を組み合わせた権力を利用しなければならない。誤った権力基盤を利用すると、A自身の権 力の低下など、意図しない影響が生じる可能性がある。 フレンチとレイヴンは、そのような性質には5つの重要なカテゴリーがあり、他のマイナーなカテゴリーを排除するものではないと主張している。その後、特に ガレス・モーガンが1986年の著書『組織のイメージ』で、さらに多くの基盤を挙げている。 |

|

Legitimate power Main article: Legitimate power Also called "positional power", legitimate power is the power of an individual because of the relative position and duties of the holder of the position within an organization. Legitimate power is formal authority delegated to the holder of the position. It is usually accompanied by various attributes of power, such as a uniform, a title, or an imposing physical office. In simple terms, power can be expressed[by whom?] as being upward or downward. With downward power, a company's superiors influence subordinates to attain organizational goals. When a company exhibits upward power, subordinates influence the decisions of their leader or leaders. |

正当な権力 詳細は「正当な権力」を参照 「地位に基づく権力」とも呼ばれる正当な権力とは、組織内での地位保有者の相対的な地位と職務に基づく個人の権力である。正当な権力は、その地位保有者に 委任された正式な権限である。通常、制服、肩書き、堂々とした執務室など、さまざまな権力の属性を伴う。 簡単に言えば、権力は上下の関係として表現できる[誰によって?]。下向きの権力では、会社の目上の者が部下に影響を与えて組織の目標を達成させる。会社 が上向きの権力を発揮する場合、部下がリーダーの意思決定に影響を与える。 |

|

Referent power Main article: Referent power Referent power is the power or ability of individuals to attract others and build loyalty. It is based on the charisma and interpersonal skills of the powerholder. A person may be admired because of a specific personal trait, and this admiration creates the opportunity for interpersonal influence. Here, the person under power desires to identify with these personal qualities and gains satisfaction from being an accepted follower. Nationalism and patriotism count towards an intangible sort of referent power. For example, soldiers fight in wars to defend the honor of the country. This is the second-least obvious power but the most effective. Advertisers have long used the referent power of sports figures for product endorsements, for example. The charismatic appeal of the sports star supposedly leads to an acceptance of the endorsement, although the individual may have little real credibility outside the sports arena.[6] Abuse is possible when someone who is likable yet lacks integrity and honesty rises to power, placing them in a situation to gain personal advantage at the cost of the group's position. Referent power is unstable alone and is not enough for a leader who wants longevity and respect. When combined with other sources of power, however, it can help a person achieve great success. |

参照対象の力 詳細は「参照対象の力」を参照 参照対象の力とは、他人を引きつけ、忠誠心を生み出す個人の力や能力である。それは権力者のカリスマ性や対人能力に基づくものである。ある個人は特定の個 人的な特徴によって賞賛されることがあり、この賞賛は対人影響の機会を生み出す。ここでは、権力下にある人は、これらの個人的な資質と同一視することを望 み、受け入れられたフォロワーであることから満足感を得る。ナショナリズムや愛国心は、無形の参照型権力の一種である。例えば、兵士たちは国の名誉を守る ために戦う。これは2番目に明白ではないが、最も効果的な権力である。広告業者は、例えば、製品推薦のためにスポーツ選手の参照型権力を長年利用してき た。スポーツ選手のカリスマ的魅力が、おそらくは推薦の受け入れにつながるが、その人物がスポーツの分野以外では信頼性が低い場合もある。[6] 好感が持てるが誠実さや正直さに欠ける人物が権力を握ると、集団の立場を犠牲にして個人的な利益を得ようとする状況に置かれるため、悪用される可能性があ る。参照者パワーは単独では不安定であり、長続きし尊敬されるリーダーとなるには十分ではない。しかし、他の権力源と組み合わせることで、その人物が大き な成功を収めるのに役立つ。 |

|

Expert power Main article: Expert power Expert power is an individual's power deriving from the skills or expertise of the person and the organization's needs for those skills and expertise. Unlike the others, this type of power is usually highly specific and limited to the particular area in which the expert is trained and qualified. When they have knowledge and skills that enable them to understand a situation, suggest solutions, use solid judgment, and generally outperform others, then people tend to listen to them. When individuals demonstrate expertise, people tend to trust them and respect what they say. As subject-matter experts, their ideas will have more value, and others will look to them for leadership in that area. |

専門家の権力 詳細は「専門家の権力」を参照 専門家の権力とは、個人のスキルや専門知識、およびそれらのスキルや専門知識に対する組織のニーズから生じる権力である。他の権力とは異なり、このタイプ の権力は通常、専門家が訓練を受け、資格を有する特定の領域に限定される。状況を理解し、解決策を提案し、確かな判断を下し、一般的に他の人々よりも優れ た能力を発揮できる知識とスキルを持っている場合、人々は彼らの意見に耳を傾ける傾向にある。個人が専門知識を示せば、人々は彼らを信頼し、彼らの言うこ とを尊重する傾向にある。主題の専門家として、彼らのアイデアはより価値を持つことになり、他の人々は彼らにその分野でのリーダーシップを期待するように なる。 |

|

Reward power Main article: Reward power Reward power depends on the ability of the power wielder to confer valued material rewards; it refers to the degree to which the individual can give others a reward of some kind, such as benefits, time off, desired gifts, promotions, or increases in pay or responsibility. This power is obvious, but it is also ineffective if abused. People who abuse reward power can become pushy or be reprimanded for being too forthcoming or 'moving things too quickly'. If others expect to be rewarded for doing what someone wants, there is a high probability that they will do it. The problem with this basis of power is that the rewarder may not have as much control over rewards as may be required. Supervisors rarely have complete control over salary increases, and managers often cannot control all actions in isolation; even a company CEO needs permission from the board of directors for some actions. When an individual uses up available rewards or the rewards do not have enough perceived value for others, their power weakens. One of the frustrations of using rewards is that they often need to be bigger each time if they are to have the same motivational impact. Even then, if rewards are given frequently, people can become so satiated by the reward it loses its effectiveness. In terms of cancel culture, the mass ostracization used to reconcile unchecked injustice and abuse of power is an "upward power." Policies for policing the internet against these processes as a pathway for creating due process for handling conflicts, abuses, and harm that is done through established processes are known as "downward power."[7] |

報酬を与える力 詳細は:報酬を与える力 報酬を与える力は、価値のある物質的報酬を与える権力者の能力に依存する。これは、個人が他の人々に何らかの報酬を与えることができる度合いを指し、例え ば、福利厚生、休暇、望まれている贈り物、昇進、給与や責任の増加などである。この力は明白であるが、乱用すれば効果的ではなくなる。報酬を与える力を乱 用する人は、強引になったり、あまりにも気前が良すぎたり、「あまりにも早く事を進めすぎたり」して叱責される可能性がある。誰かの望むことをすれば報酬 がもらえると期待されれば、高い確率でその行動がとられることになる。この権力の基盤の問題は、報酬を与える側が、必要なだけの報酬をコントロールできな い可能性があることだ。上司は昇給を完全にコントロールできることはまれであり、マネージャーは個々の行動をすべてコントロールできないことが多い。企業 のCEOでさえ、一部の行動については取締役会の許可が必要である。個人が利用可能な報酬を使い果たしたり、報酬が他者にとって十分な価値を感じられない ものである場合、その効力は弱まる。 報酬を使用する際のフラストレーションのひとつは、同じモチベーション効果を得るためには、報酬を毎回より大きくする必要があることが多いことだ。 それでも、報酬が頻繁に与えられると、人々は報酬に飽きてしまい、その効果は失われてしまう。 キャンセル文化という観点では、抑制されない不正や権力の乱用を是正するために集団で排斥することが「上向きの権力」である。確立されたプロセスを通じて 対立、乱用、被害に対処するための適正手続きを創出する手段として、インターネットを監視する政策は「下向きの権力」として知られている。[7] |

| Coercive power Main article: Coercive power See also: Coercive control Coercive power is the application of negative influences. It includes the ability to defer or withhold other rewards. The desire for valued rewards or the fear of having them withheld can ensure the obedience of those under power. Coercive power tends to be the most obvious but least effective form of power, as it builds resentment and resistance from the people who experience it. Threats and punishment are common tools of coercion. Implying or threatening that someone will be fired, demoted, denied privileges, or given undesirable assignments – these are characteristics of using coercive power. Extensive use of coercive power is rarely appropriate in an organizational setting, and relying on these forms of power alone will result in a very cold, impoverished style of leadership. This is a type of power commonly seen in the fashion industry by coupling with legitimate power; it is referred to in the industry-specific literature as "glamorization of structural domination and exploitation".[8] |

強制力 詳細は:強制力 関連項目:強制管理 強制力とは、否定的な影響力の行使である。他の報酬を延期したり、保留したりする能力も含まれる。価値ある報酬への欲求や、報酬が保留されることへの恐れ は、権力下にある者の服従を確実なものとする。強制力は、最も明白であるが、最も効果の低い権力の形である傾向がある。なぜなら、それを経験する人々から 恨みや抵抗を生み出すからである。脅しや罰は、強制の一般的な手段である。誰かを解雇、降格、特権の剥奪、望ましくない任務を与えるなどとほのめかす、あ るいは脅すことは、強制力の行使の特徴である。組織内において強制力の行使が頻繁に行われることはほとんど適切ではなく、このような権力形態のみに頼るこ とは、非常に冷淡で貧弱なリーダーシップのスタイルにつながる。これは、ファッション業界で一般的に見られる権力の一種であり、合法的な権力と結びついて いる。業界特有の文献では、「構造的支配と搾取の美化」と呼ばれている。[8] |

|

Principles in interpersonal relationships According to Laura K. Guerrero and Peter A. Andersen in Close Encounters: Communication in Relationships:[9] Power as a perception: Power is a perception in the sense that some people can have objective power but still have trouble influencing others. People who use power cues and act powerfully and proactively tend to be perceived as powerful by others. Some people become influential even though they do not overtly use powerful behavior. Power as a relational concept: Power exists in relationships. The issue here is often how much relative power a person has in comparison to one's partner. Partners in close and satisfying relationships often influence each other at different times in various arenas. Power as resource-based: Power usually represents a struggle over resources. The more scarce and valued resources are, the more intense and protracted the power struggles. The scarcity hypothesis indicates that people have the most power when the resources they possess are hard to come by or are in high demand. However, scarce resources lead to power only if they are valued within a relationship. The principle of least interest and dependence power: The person with less to lose has greater power in the relationship. Dependence power indicates that those who are dependent on their relationship or partner are less powerful, especially if they know their partner is uncommitted and might leave them. According to interdependence theory, the quality of alternatives refers to the types of relationships and opportunities people could have if they were not in their current relationship. The principle of least interest suggests that if a difference exists in the intensity of positive feelings between partners, the partner who feels the most positive is at a power disadvantage. There's an inverse relationship between interest in a relationship and the degree of relational power. Power as enabling or disabling: Power can be enabling or disabling. Research[citation needed] has shown that people are more likely to have an enduring influence on others when they engage in dominant behavior that reflects social skill rather than intimidation. Personal power is protective against pressure and excessive influence by others and/or situational stress. People who communicate through self-confidence and expressive, composed behavior tend to be successful in achieving their goals and maintaining good relationships. Power can be disabling when it leads to destructive patterns of communication. This can lead to the chilling effect, where the less powerful person often hesitates to communicate dissatisfaction, and the demand withdrawal pattern, which is when one person makes demands and the other becomes defensive and withdraws (Mawasha, 2006). Both effects have negative consequences for relational satisfaction. Power as a prerogative: The prerogative principle states that the partner with more power can make and break the rules. Powerful people can violate norms, break relational rules, and manage interactions without as much penalty as powerless people. These actions may reinforce the powerful person's dependence on power. In addition, the more powerful person has the prerogative to manage both verbal and nonverbal interactions. They can initiate conversations, change topics, interrupt others, initiate touch, and end discussions more easily than less powerful people. (See expressions of dominance.) |

対人関係における原則 Laura K. GuerreroとPeter A. Andersenは、著書『Close Encounters: Communication in Relationships』の中で、次のように述べている。[9] 認識としての権力:権力とは、一部の人が客観的な権力を持ちながらも、他者に影響を与えるのに苦労しているという意味で、認識されるものである。権力の兆 候を示し、力強く、積極的に行動する人は、他人から力強い人物として認識される傾向にある。 権力を行使する行動をあからさまに取らない人でも、影響力を持つようになる場合もある。 関係性概念としての権力:権力は人間関係の中に存在する。 ここで問題となるのは、多くの場合、ある人物がパートナーと比較してどれほどの相対的な権力を持っているかということである。 親密で満足のいく関係にあるパートナーは、さまざまな場面で互いに影響を与え合うことが多い。 リソースに基づく力:力は通常、リソースをめぐる争いを意味する。希少で価値のあるリソースであればあるほど、権力闘争は激しく長期化する。希少性仮説 は、人が持つリソースが入手困難であったり、需要が高い場合、その人には最も大きな力があることを示している。しかし、希少なリソースが力につながるの は、そのリソースが関係の中で価値がある場合のみである。 最小限の利害と依存力:失うものが少ない人の方が、関係において大きな力を持つ。依存力は、関係やパートナーに依存している人の方が、特に相手が自分に対 して無関心で、自分から離れていく可能性があることを知っている場合には、より力が弱いことを示している。相互依存理論によると、代替案の質とは、現在の 関係にない場合に人々が持つ可能性のある関係や機会の種類を指す。最小関心原則は、パートナー間の肯定的な感情の強さに違いがある場合、最も肯定的な感情 を持つパートナーの方が、力の面で不利であることを示唆している。人間関係に対する関心と人間関係における力の度合いには逆相関の関係がある。 力を発揮できるか、あるいは力を奪われるか:力は人を助けることもあれば、力を奪うこともある。研究[要出典]によると、威圧的な態度よりもむしろ社交性 を反映する支配的な行動を取る場合の方が、他者に永続的な影響を与える可能性が高いことが示されている。個人の力は、他者からの圧力や過剰な影響、および /または状況的なストレスから身を守る。自信に満ち、表現力豊かで落ち着いた態度でコミュニケーションを行う人は、目標を達成し、良好な人間関係を維持す る傾向にある。 権力が破壊的なコミュニケーションパターンにつながる場合、それは有害となる可能性がある。 これは、非力な人が不満を伝えることをためらう「凍結効果」や、一方が要求を出し、他方が防御的になって引き下がる「要求撤回パターン」につながる可能性 がある(Mawasha, 2006)。 いずれのケースも、人間関係の満足度に悪影響を及ぼす。 特権としての力:特権の原則は、より強い力を持つパートナーがルールを定め、破ることができると主張する。力のある人は、規範を破り、人間関係のルールを 破り、無力な人ほど罰せられることなく対人関係を管理することができる。こうした行動は、力のある人の権力への依存を強める可能性がある。さらに、より力 のある人は、言語的および非言語的な対人関係を管理する特権を持つ。会話の主導権を握り、話題を変え、他者の会話を遮り、接触を始め、議論を打ち切ること も、権力を持たない人々よりも容易に行うことができる。(支配的な表現を参照) |

|

Rational choice framework Game theory, with its foundations in the Walrasian theory of rational choice, is increasingly used in various disciplines to help analyze power relationships. One rational-choice definition of power is given by Keith Dowding in his book Power. In rational choice theory, human individuals or groups can be modelled as 'actors' who choose from a 'choice set' of possible actions in order to try to achieve desired outcomes. An actor's 'incentive structure' comprises (its beliefs about) the costs associated with different actions in the choice set and the likelihoods that different actions will lead to desired outcomes. |

合理的選択の枠組み ワルラスの合理的選択理論を基礎とするゲーム理論は、権力関係の分析に役立つものとして、さまざまな分野でますます利用されるようになってきている。 権力に関する合理的選択の定義のひとつは、キース・ダウディングの著書『Power』で提示されている。 合理的選択理論では、人間個人またはグループは、望ましい結果を達成しようとして、可能な行動の「選択肢」から選択する「行為者」としてモデル化される。 行為者の「インセンティブ構造」は、選択肢における異なる行動に関連するコスト(その信念)と、異なる行動が望ましい結果につながる可能性から構成され る。 |

|

In this setting, we can differentiate between: outcome power – the ability of an actor to bring about or help bring about outcomes; social power – the ability of an actor to change the incentive structures of other actors in order to bring about outcomes. This framework can be used to model a wide range of social interactions where actors have the ability to exert power over others. For example, a 'powerful' actor can take options away from another's choice set; can change the relative costs of actions; can change the likelihood that a given action will lead to a given outcome; or might simply change the other's beliefs about its incentive structure. As with other models of power, this framework is neutral as to the use of 'coercion'. For example, a threat of violence can change the likely costs and benefits of different actions; so can a financial penalty in a 'voluntarily agreed' contract, or indeed a friendly offer. |

この設定では、次のものを区別することができる。 結果力(outcome power) - 行為者が結果をもたらす、または結果をもたらすのを助ける能力。 社会力(social power) - 行為者が結果をもたらすために他の行為者のインセンティブ構造を変える能力。 この枠組みは、行為者が他者に影響力を及ぼす能力を持つ、幅広い社会的相互作用のモデル化に利用することができる。例えば、「強力な」行為者は、他者の選 択肢を奪うことができる。また、行動の相対的なコストを変えることもできる。特定の行動が特定の結果につながる可能性を変えることもできる。あるいは、単 に他者のインセンティブ構造に関する信念を変えることさえできる。 他の権力モデルと同様に、この枠組みでは「強制」の使用については中立である。例えば、暴力の脅威は異なる行動のコストと利益の見込みを変えることができる。「自主的に合意した」契約における金銭的ペナルティや、友好的な申し出も同様である。 |

|

Cultural hegemony In the Marxist tradition, the Italian writer Antonio Gramsci elaborated on the role of ideology in creating a cultural hegemony, which becomes a means of bolstering the power of capitalism and of the nation-state. Drawing on Niccolò Machiavelli in The Prince and trying to understand why there had been no Communist revolution in Western Europe while it was claimed there had been one in Russia, Gramsci conceptualised this hegemony as a centaur, consisting of two halves. The back end, the beast, represented the more classic material image of power: power through coercion, through brute force, be it physical or economic. But the capitalist hegemony, he argued, depended even more strongly on the front end, the human face, which projected power through 'consent'. In Russia, this power was lacking, allowing for a revolution. However, in Western Europe, specifically in Italy, capitalism had succeeded in exercising consensual power, convincing the working classes that their interests were the same as those of capitalists. In this way, a revolution had been avoided. While Gramsci stresses the significance of ideology in power structures, Marxist-feminist writers such as Michele Barrett stress the role of ideologies in extolling the virtues of family life. The classic argument to illustrate this point of view is the use of women as a 'reserve army of labour'. In wartime, it is accepted that women perform masculine tasks, while after the war, the roles are easily reversed. Therefore, according to Barrett, the destruction of capitalist economic relations is necessary but not sufficient for the liberation of women.[10] |

文化的ヘゲモニー マルクス主義の伝統において、イタリアの作家アントニオ・グラムシは、資本主義と国民国家の権力を強化する手段となる文化的なヘゲモニー(覇権)を生み出 すイデオロギーの役割について詳しく論じている。 グラムシは、ニッコロ・マキャベリの『君主論』を引用し、ロシアでは共産主義革命が起こったと主張されているにもかかわらず西ヨーロッパでは起こらなかっ た理由を理解しようと試み、このヘゲモニーを2つの部分からなるケンタウロスとして概念化した。後部、つまり獣の部分は、より古典的な権力の物質的イメー ジを表している。すなわち、物理的であれ経済的であれ、強制や武力による権力である。しかし、資本主義のヘゲモニーは、前部、つまり人間の顔の部分に、よ り強く依存していると彼は主張した。この顔の部分は、「同意」を通じて権力を投影する。ロシアではこの権力が欠如していたため、革命が起こった。しかし西 ヨーロッパ、特にイタリアでは、資本主義は合意に基づく権力をうまく行使し、労働者階級に自分たちの利益は資本家の利益と同じであると信じ込ませることに 成功した。こうして革命は回避された。 グラムシが権力構造におけるイデオロギーの重要性を強調する一方で、ミケーレ・バレットのようなマルクス主義フェミニストの作家たちは、家庭生活の美徳を 称賛するイデオロギーの役割を強調している。この見解を説明する典型的な論点は、「予備労働力としての女性」の使用である。戦時中には、女性が男性的な役 割を担うことが容認されるが、戦後はその役割が容易に逆転する。したがって、バレットによれば、資本主義経済関係の破壊は、女性の解放には必要ではあるが 十分ではないのである。 |

|

Tarnow Eugen Tarnow considers what power hijackers have over air plane passengers and draws similarities with power in the military.[11] He shows that power over an individual can be amplified by the presence of a group. If the group conforms to the leader's commands, the leader's power over an individual is greatly enhanced, while if the group does not conform, the leader's power over an individual is nil. |

タルノフ オイゲン・タルノフは、ハイジャック犯が飛行機の乗客に対して持つ権力を考察し、軍隊における権力との類似点を指摘している。[11] タルノフは、個人に対する権力は集団の存在によって増幅される可能性があることを示している。集団がリーダーの命令に従順である場合、リーダーの個人に対 する権力は大幅に強化されるが、集団が従順でない場合、リーダーの個人に対する権力はゼロである。 |

|

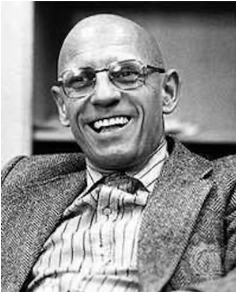

Foucault See also: Biopower For Michel Foucault, the real power will always rely on the ignorance of its agents. No single human, group, or actor runs the dispositif (machine or apparatus), but power is dispersed through the apparatus as efficiently and silently as possible, ensuring its agents do whatever is necessary. It is because of this action that power is unlikely to be detected and remains elusive to 'rational' investigation. Foucault quotes a text reputedly written by political economist Jean Baptiste Antoine Auget de Montyon, entitled Recherches et considérations sur la population de la France (1778), but turns out to be written by his secretary Jean-Baptise Moheau (1745–1794), and by emphasizing biologist Jean-Baptiste Lamarck, who constantly refers to milieus as a plural adjective and sees into the milieu as an expression as nothing more than water, air, and light confirming the genus within the milieu, in this case the human species, relates to a function of the population and its social and political interaction in which both form an artificial and natural milieu. This milieu (both artificial and natural) appears as a target of intervention for power, according to Foucault, which is radically different from the previous notions on sovereignty, territory, and disciplinary space interwoven into social and political relations that function as a species (biological species).[12] Foucault originated and developed the concept of "docile bodies" in his book Discipline and Punish. He writes, "A body is docile that may be subjected, used, transformed and improved.[13] |

フーコー 関連項目: 生権力(バイオパワー) ミシェル・フーコーによれば、真の権力は常にその代理人たちの無知に依存している。装置(機械または器具)を動かしているのは、単独の人間、集団、または 行為者ではなく、権力は装置を通じて可能な限り効率的に、かつ静かに分散され、その代理人たちが必要なことを何でも行うようにしている。この作用があるた めに、権力は発見されにくく、「理性的」な調査からは捉えどころのないものとなる。フーコーは、政治経済学者ジャン・バティスト・アントワーヌ・オーゲ・ ド・モンティヨンが著したとされる『フランス人口に関する研究と考察』(1778年)という文章を引用しているが、実際には秘書のジャン=バティスト・モ オ(1745年~1794年)が書いたものであり、生物学者ジャン 常に環境を複数形の形容詞として参照し、環境を表現するものとして、水、空気、光といった環境内の属を裏付けるもの以上の何者でもないものとして捉える ジャン=バティスト・ラマルクを強調することで、この場合、人間という種が、人口とその社会的・政治的相互作用という機能に関連し、両者が人工的および自 然的な環境を形成していることを明らかにしている。この環境(人工的および自然的)は、フーコーによれば、権力による介入の対象として現れる。これは、生 物学的種として機能する社会および政治関係に織り込まれた主権、領土、規律空間に関する従来の概念とは根本的に異なるものである。[12] フーコーは著書『監獄の誕生』において、「従順な身体」という概念を創始し、発展させた。「従順な身体とは、従属させられ、利用され、変容され、改善され る身体である」と彼は書いている。[13] |

|

Clegg Stewart Clegg proposes another three-dimensional model with his "circuits of power"[14] theory. This model likens the production and organization of power to an electric circuit board consisting of three distinct interacting circuits: episodic, dispositional, and facilitative. These circuits operate at three levels: two are macro and one is micro. The episodic circuit is at the micro level and is constituted of irregular exercise of power as agents address feelings, communication, conflict, and resistance in day-to-day interrelations. The outcomes of the episodic circuit are both positive and negative. The dispositional circuit is constituted of macro level rules of practice and socially constructed meanings that inform member relations and legitimate authority. The facilitative circuit is constituted of macro level technology, environmental contingencies, job design, and networks, which empower or disempower and thus punish or reward agency in the episodic circuit. All three independent circuits interact at "obligatory passage points", which are channels for empowerment or disempowerment. |

クレッグ スチュワート・クレッグは、「権力の回路」[14]理論で、別の3次元モデルを提案している。このモデルでは、権力の生産と組織化を、3つの異なる相互作 用回路からなる電気回路基板に例えている。すなわち、エピソード的、素質的、促進的である。これらの回路は3つのレベルで機能する。2つはマクロレベル、 もう1つはミクロレベルである。エピソード回路はミクロレベルにあり、エージェントが日々の相互関係において感情、コミュニケーション、葛藤、抵抗に対処 する際に、不規則に行使される権力から構成される。エピソード回路の結果は、ポジティブなものとネガティブなものがある。素質回路は、メンバー間の関係や 正当な権限を伝えるマクロレベルの実践規則と社会的に構築された意味から構成される。促進回路は、エピソード回路におけるエージェントに権限を与えたり 奪ったりし、その結果、処罰したり報酬を与えたりするマクロレベルのテクノロジー、環境要因、職務設計、ネットワークから構成される。3つの独立した回路 はすべて、「義務的な通過点」で相互作用する。これは、権限付与や権限剥奪の経路である。 |

|

Galbraith John Kenneth Galbraith (1908–2006) in The Anatomy of Power (1983)[15] summarizes the types of power as "condign" (based on force), "compensatory" (through the use of various resources) or "conditioned" (the result of persuasion),[citation needed] and the sources of power as "personality" (individuals), "property" (power-wielders' material resources), and/or "organizational" (from sitting higher in an organisational power structure).[16] |

ガルブレイス ジョン・ケネス・ガルブレイス(1908年 - 2006年)は、『権力の解剖学』(1983年)[15]において、権力のタイプを「正当な」(力に基づく)、「補償的な」(さまざまなリソースの使用に よる)、または「条件付きの (説得の結果)[要出典]、権力の源泉として「人格」(個人)、「財産」(権力者の物的資源)、および/または「組織的」(組織権力構造の上位に位置する こと)を挙げている。[16] |

| Gene Sharp Gene Sharp, an American professor of political science, believes that power ultimately depends on its bases. Thus, a political regime maintains power because people accept and obey its dictates, laws, and policies. Sharp cites the insight of Étienne de La Boétie. Sharp's key theme is that power is not monolithic; that is, it does not derive from some intrinsic quality of those who are in power. For Sharp, political power, the power of any state – regardless of its particular structural organization – ultimately derives from the subjects of the state. His fundamental belief is that any power structure relies upon the subjects' obedience to the orders of the ruler(s). If subjects do not obey, leaders have no power.[17] His work is thought to have been influential in the overthrow of Slobodan Milošević, in the 2011 Arab Spring, and other nonviolent revolutions.[18] |

ジーン・シャープ アメリカの政治学者ジーン・シャープは、権力は最終的にはその基盤に依存すると考えている。したがって、政治体制が権力を維持するのは、人々がその指示、 法律、政策を受け入れ、従うからである。シャープは、エティエンヌ・ド・ラ・ボエティの洞察を引用している。 シャープの主要なテーマは、権力は単一ではないということ、つまり、権力を持つ人々の本質的な性質から生じるものではないということである。シャープに とって、政治権力、すなわち国家の権力は、その特定の構造的組織に関わらず、究極的には国家の国民から生じるものである。彼の基本的な信念は、あらゆる権 力構造は、支配者(複数)の命令に対する国民の服従に依存しているというものである。国民が服従しなければ、指導者には権力はない。 彼の研究は、スロボダン・ミロシェヴィッチの失脚、2011年のアラブの春、その他の非暴力革命に影響を与えたと考えられている。 |

|

Björn Kraus Björn Kraus deals with the epistemological perspective on power regarding the question of the possibilities of interpersonal influence by developing a special form of constructivism (named relational constructivism).[19] Instead of focusing on the valuation and distribution of power, he asks first and foremost what the term can describe at all.[20] Coming from Max Weber's definition of power,[21] he realizes that the term power has to be split into "instructive power" and "destructive power".[22]: 105 [23]: 126 More precisely, instructive power means the chance to determine the actions and thoughts of another person, whereas destructive power means the chance to diminish the opportunities of another person.[20] How significant this distinction really is, becomes evident by looking at the possibilities of rejecting power attempts: Rejecting instructive power is possible; rejecting destructive power is not. By using this distinction, proportions of power can be analyzed in a more sophisticated way, helping to sufficiently reflect on matters of responsibility.[23]: 139 f. This perspective permits people to get over an "either-or-position" (either there is power or there is not), which is common, especially in epistemological discourses about power theories,[24][25][26] and to introduce the possibility of an "as well as-position".[23]: 120 |

ビョーン・クラウス ビョーン・クラウスは、特殊な形の構成主義(関係構築主義と名付けられた)を発展させることで、権力に関する認識論的観点から、対人関係における影響力の 可能性に関する問題に取り組んでいる。[19] 彼は、権力の評価や分配に焦点を当てるのではなく、まず何よりも、この用語が何を表現しうるのかを問う。[20] マックス・ウェーバーの権力の定義に由来する彼は、 権力という用語は「説得的権力」と「破壊的権力」に分割されなければならないと認識している。[22]: 105 [23]: 126 より正確に言えば、説得的権力とは他者の行動や思考を決定する可能性を意味し、他方、破壊的権力とは他者の機会を減少させる可能性を意味する。[20] この区別が実際どれほど重要であるかは、権力行使を拒否する可能性を検討することで明らかになる。教育的権力を拒絶することは可能であるが、破壊的権力を 拒絶することはできない。この区別を用いることで、権力の割合をより洗練された方法で分析することができ、責任の問題について十分に考察するのに役立つ。 [23]: 139 f. この視点は、人々が「どちらか一方か」という立場(権力があるかないか)を乗り越えることを可能にする。権力があるかないか)という、特に権力理論に関す る認識論的言説でよく見られる考え方を乗り越え、「~であると同時に~である」という可能性を導入することができる。[23]: 120 |

|

Unmarked categories The idea of unmarked categories originated in feminism.[27] As opposed to looking at social difference by focusing on what or whom is perceived to be different, theorists who use the idea of unmarked categories insist that one must also look at how whatever is "normal" comes to be perceived as unremarkable and what effects this has on social relations. Attending the unmarked category is thought to be a way to analyze linguistic and cultural practices to provide insight into how social differences, including power, are produced and articulated in everyday occurrences.[28] According to the idea of unmarked categories, when the cultural practices of people who occupy positions of relative power or can more easily exercise power seem obvious, they tend not to be explicitly articulated and therefore are perceived as default or baseline practices against which others are evaluated as different, deviant, or aberrant. The unmarked category becomes the standard against which to measure everything else. For example, it is posited[citation needed] that if a protagonist's race is not indicated, most Western[further explanation needed] readers will assume the protagonist is white; if a sexual identity is not indicated, it will be assumed the protagonist is heterosexual; if the gender of a body is not indicated, it is assumed to be male; if no disability is indicated, it will be assumed the protagonist is able-bodied. These assumptions do not, however, mean the unmarked category is superior, preferable, or more "natural," nor that the practices associated with the unmarked category require less social effort to enact.[28] Although the unmarked category is typically not explicitly noticed and often goes overlooked, it is still necessarily visible.[29] As visible but unnoticed and unremarkable, membership in the unmarked category can be an index of power.[citation needed] For example, whiteness forms an unmarked category not commonly noticeable to the powerful,[citation needed] as they often fall within this category. Social groups can hold this view of power in terms of a variety of social distinctions, such as race, class, gender, ability, and sexuality. |

無印カテゴリー 無印カテゴリーという概念はフェミニズムから生まれたものである。[27] 社会的な差異を、何が、あるいは誰が異なるものとして認識されているかに注目して見ることとは対照的に、無印カテゴリーの概念を用いる理論家たちは、どの ようなものであれ「普通」と認識されているものが、どのようにして注目に値しないものとして認識されるようになったのか、また、それが社会関係にどのよう な影響を及ぼしているのかにも目を向けなければならないと主張する。マークされていないカテゴリーに注目することは、言語的および文化的慣習を分析し、権 力を含む社会的差異が日常的な出来事の中でどのように生み出され、表現されるのかを洞察するひとつの方法であると考えられている。 無印カテゴリーの考え方によると、相対的な権力を持つ立場にある人々や、権力をより容易に行使できる人々の文化的慣習が明白である場合、それらは明示的に 表現されない傾向があり、そのため、それらをデフォルトまたはベースラインの慣習と見なし、それに対して他者が異なる、逸脱した、異常であると評価され る。無印カテゴリーは、他のすべてを測定する基準となる。例えば、主人公の民族性が示されていない場合、ほとんどの欧米人(さらなる説明が必要)の読者は 主人公が白人であると想定する。性的アイデンティティが示されていない場合、主人公は異性愛者であると想定される。身体の性が示されていない場合、男性で あると想定される。障害が示されていない場合、主人公は健常者であると想定される。しかし、これらの想定は、マークされていないカテゴリーが優れている、 望ましい、あるいはより「自然」であることを意味するものではない。また、マークされていないカテゴリーに関連する慣行が、実行に移すために必要な社会的 努力がより少ないことを意味するものでもない。[28] 無印カテゴリーは通常、明確に認識されることはなく、見落とされることも多いが、それでもなお、必ず目に見えるものである。[29] 目に見えるが、注目されない、注目に値しないものとして、無印カテゴリーのメンバーシップは、権力の指標となりうる。[要出典] 例えば、白人であることは、権力者にとっては一般的には目立たない無印カテゴリーを形成するが、[要出典] 彼らはしばしばこのカテゴリーに属している。社会集団は、人種、階級、性別、能力、性的指向など、さまざまな社会的区別という観点から、この権力観を持つ ことができる。 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Power_%28social_and_political%29 |

★一般的な権力の用語法は我々のいうところの、政

治的権力であり、しばしば「抑圧的権力(opprestive power)」と呼ばれるものである(→「権力概念の考察」)。

抑圧的権力の3社会要素

それらの3要素が目的とする5つの機能

生命に介入するテクノロジー行使によって実現させられる権力

その背景にある理念

●暴力について

私が与える暴力の定義とは、「人を従属させる破壊的な強制力のこと」である。〈従属させる強 制力〉すなわち〈暴力〉の帰結とは、動産の破壊、人間や 動物の殺傷などがある。このために、人は暴力の被害が被らないように、命乞いのように懇願したり、(因果関係の認識として)謝る必要のない謝罪を口にす る。通常は、暴力概念は権力の発露として捉えることができるが(→「ソレルの暴力論」を参照)、以下の、ハンナ・アーレントの暴力概念は、そのように捉え ない特異的な解釈なので、注意が必要である。暴力の反対語は、ある意味空間(A)においては、非暴力であり、非暴力が含意するものは、誰でも想像がつくよ うに「平和」である。他方、「人を従属させる非破壊的な強制力」としての「権威」を暴力に対峙するもの、つまり反対語/反対概念とみなす立場もある。それ が、ハンナ・アーレントの暴力概念であり、この概念は、アーレントが影響を受けた夫ハインリッヒ・ブリュッヒャーとヴァルター・ベンヤミンの影響を受けて いるものと、私(池田)は考えている(→「暴力:その定義」)。

■フーコーの権力概念——生産的権力論

「私は、権力関係の新たなエコノミーをさ らに推し進めるための別の方法を提案したい。それは、より経験的で、より直接的に現在の状況に関連しており、理論と 実践の間のより多くの関係を暗示するものである。それは、さまざまな権力形態に対する抵抗の形態を起点とするものである。別のメタファーを用いるなら、こ の抵抗 を化学反応における触媒として利用し、権力関係を明らかにし、その位置を特定し、その適用点と使用される手法を見つけ出すことである。権力をその内部の合理性という観 点から分析するのではなく、権力関係を戦略の対立を通じて分析することである。権力行使の定義に戻ろう。それは、ある行動が他の可能な行動 の領域を構造化 する方法である。したがって、権力関係にふさわしいのは、行動に対する行動様式である。つまり、権力関係は社会の結びつきに深く根ざしており、社会の上に 再構成されることはない。社会の上に再構成されることは、おそらく根本的な消滅を夢見ることができる補足的な構造としてではない。いずれにせよ、社会で生 きるということは、他の行動に対する行動が可能であるように生きるということであり、実際、進行中である。権力関係のない社会は、抽象的な ものにすぎな い。これは、特定の社会における権力関係の分析、その歴史的形成、強さや脆さの源泉、一部を変革したり、他を廃止したりするために必要な条件を、より政治 的に必要とするものである。権力関係のない社会はありえないとい う主張は、確立された権力関係が必然であるとか、あるいは、いかなる場合でも権力が社会の 中心に宿命として存在し、それを弱めることができないという主張ではない。むしろ、権力関係の分析、精査、そして権力関係と自由の非直線性との間の「対 立」を問題視することは、あらゆる社会的存在に内在する永続的な政治的課題であると言えるだろう。実際、権力関係と闘争の戦略の間には、相互に惹きつけ合 い、絶え間なく結びつき、そして絶え間なく反転し合うという関係がある。権力関係は、つねに二つの敵対者間の対立となる可能性がある。同様に、社会におけ る敵対者間の関係は、つねに権力のメカニズムが作動する余地がある。この不安定さの結果、同じ出来事や同じ変容を、闘争の歴史の内側から、あるいは権力関 係の観点から解読できる能力が生まれる。その結果生じる解釈は、同じ歴史的背景を参照しているとはいえ、同じ意味の要素や同じつながり、同じ種類の理解可 能性から構成されるものではない。また、2つの分析はそれぞれ、もう一方を参照していなければならない。実際、2つの解釈の相違こそが、多数の人間社会に 存在する「支配」の根本的な現象を明らかにするのである。」

| The Subject and

Power [pdf] with password Michel Foucault Critical Inquiry 8 (4):777-795 (1982) Copy BIBTEX Abstract I would like to suggest another way to go further toward a new economy of power relations, a way which is more empirical, more directly related to our present situation, and which implies more relations between theory and practice. It consists of taking the forms of resistance against different forms of power as a starting point. To use another metaphor, t consists of using this resistance as a chemical catalyst so as to bring to light power relations, locate their position, and find out their point of application and the methods used. Rather than analyzing power from the point of view of its internal rationality, it consists of analyzing power relations through the antagonism of strategies.[…]Let us come back to the definition of the exercise of power as a way in which certain actions may structure the field of other possible actions. What, therefore, would be proper to a relationship of power is that it be a mode of action upon actions. That is to say, power relations are rooted deep in the social nexus, not reconstituted "above" society as a supplementary structure whose radical effacement one could perhaps dream of. In any case, to live in a society is to live in such a way that action upon other actions is possible-- and in fact ongoing. A society without power relations can only be an abstraction. Which, be it said in passing, makes all the more politically necessary the analysis of power relations in a given society, their historical formation, the source of their strength or fragility, the conditions which are necessary to transform some or to abolish others. For to say that there cannot be a society without power relations is not to say either that those which are established are necessary or, in any case, that power constitutes a fatality at the heart of societies, such that it cannot be undermined. Instead, I would say that the analysis, elaboration, and bringing into question of power relations and the "agonism" between power relations and the instransitivity of freedom is a permanent political task inherent in all social existence.[…]In effect, between a relationship of power and a strategy of struggle there is a reciprocal appeal, a perpetual linking and a perpetual reversal. At every moment the relationship of power may become a confrontation between two adversaries. Equally, the relationship between adversaries in society may, at every moment, give place to the putting into operation of mechanisms of power. The consequence of this instability is the ability to decipher the same events and the same transformations either from inside the history of struggle or from the standpoint of the power relationships. The interpretations which result will not consist of the same elements of meaning or the same links or the same types of intelligibility, although they refer to the same historical fabric, and each of the two analyses must have reference to the other. In fact, it is precisely the disparities between the two readings which make visible those fundamental phenomena of "domination" which are present in a large number of human societies.Michel Foucault has been teaching at the Collège de France since 1970. His works include Madness and Civilization , The Birth of the Clinic , Discipline and Punish , and History of Sexuality , the first volume of a projected five-volume study |

主体と権力 ミシェル・フーコー クリティカル・インクワイアリー 8 (4):777-795 (1982) BIBTEXのコピー 要約 私は、権力関係の新たなエコノミーをさらに推し進めるための別の方法を提案したい。それは、より経験的で、より直接的に現在の状況に関連しており、理論と 実践の間のより多くの関係を暗示するものである。それは、さまざまな権力形態に対する抵抗の形態を起点とするものである。別の比喩を用いるなら、この抵抗 を化学触媒として利用し、権力関係を明らかにし、その位置を特定し、その適用点と使用される手法を見つけ出すことである。権力をその内部の合理性という観 点から分析するのではなく、権力関係を戦略の対立を通じて分析することである。権力行使の定義に戻ろう。それは、ある行動が他の可能な行動の領域を構造化 する方法である。したがって、権力関係にふさわしいのは、行動に対する行動様式である。つまり、権力関係は社会の結びつきに深く根ざしており、社会の上に 再構成されることはない。社会の上に再構成されることは、おそらく根本的な消滅を夢見ることができる補足的な構造としてではない。いずれにせよ、社会で生 きるということは、他の行動に対する行動が可能であるように生きるということであり、実際、進行中である。権力関係のない社会は、抽象的なものにすぎな い。これは、特定の社会における権力関係の分析、その歴史的形成、強さや脆さの源泉、一部を変革したり、他を廃止したりするために必要な条件を、より政治 的に必要とするものである。権力関係のない社会はありえないという主張は、確立された権力関係が必然であるとか、あるいは、いかなる場合でも権力が社会の 中心に宿命として存在し、それを弱めることができないという主張ではない。むしろ、権力関係の分析、精査、そして権力関係と自由の非直線性との間の「対 立」を問題視することは、あらゆる社会的存在に内在する永続的な政治的課題であると言えるだろう。実際、権力関係と闘争の戦略の間には、相互に惹きつけ合 い、絶え間なく結びつき、そして絶え間なく反転し合うという関係がある。権力関係は、つねに二つの敵対者間の対立となる可能性がある。同様に、社会におけ る敵対者間の関係は、つねに権力のメカニズムが作動する余地がある。この不安定さの結果、同じ出来事や同じ変容を、闘争の歴史の内側から、あるいは権力関 係の観点から解読できる能力が生まれる。その結果生じる解釈は、同じ歴史的背景を参照しているとはいえ、同じ意味の要素や同じつながり、同じ種類の理解可 能性から構成されるものではない。また、2つの分析はそれぞれ、もう一方を参照していなければならない。実際、2つの解釈の相違こそが、多数の人間社会に 存在する「支配」の根本的な現象を明らかにするのである。ミシェル・フーコーは1970年よりコレージュ・ド・フランスで教鞭をとっている。著書に『狂気 と文明』、『臨床の誕生』、『監獄の誕生』、『性の歴史』などがある。『性の歴史』は5巻からなる研究計画の第1巻である。 |

| https://philpapers.org/rec/FOUTSA |

|

権力の理論家たち

★権力と言説、および統治性

一方に権力の言説があり、そ れに対峙して、他方に権力に対 抗するもうひとつの言説があるのではない。

言説は、力関係の場における 戦術的な要素あるいは塊であ る。

同じ一つの戦略の内部で、相 異なる、いや矛盾する言説すら あり得る。反対に、それらの言説は、相対立する戦略の間で姿を変えることなく循環することもあり得る。

***

これらの言説に問いかけねばならぬのは、二つのレベルにおいて であり、それはこれらの言説の戦術的生産性(権力と知とのいかなる相互作用をそれは保証しているのか)と、その戦略的統合(いかなる局面、いかなる力関係 が、その時生ずる様々な対決のかくかくの情景においてこれらの言説の使用を必要たらしめているのか)なのである。

M・フーコー(渡辺守章訳)『知への意志』新潮社、 p.131、1986年

★

★対抗権力(

Counterpower)

|

Counterpower Main article: Dual power The term 'counter-power' (sometimes written 'counterpower') is used in a range of situations to describe the countervailing force that can be utilised by the oppressed to counterbalance or erode the power of elites. A general definition has been provided by the anthropologist David Graeber as 'a collection of social institutions set in opposition to the state and capital: from self-governing communities to radical labor unions to popular militias'.[30] Graeber also notes that counter-power can also be referred to as 'anti-power' and 'when institutions [of counter-power] maintain themselves in the face of the state, this is usually referred to as a 'dual power' situation'.[30] Tim Gee, in his 2011 book Counterpower: Making Change Happen,[31] put forward the theory that those disempowered by governments' and elite groups' power can use counterpower to counter this.[32] In Gee's model, counterpower is split into three categories: idea counterpower, economic counterpower, and physical counterpower.[31] Although the term has come to prominence through its use by participants in the global justice/anti-globalization movement of the 1990s onwards,[33] the word has been used for at least 60 years; for instance, Martin Buber's 1949 book 'Paths in Utopia' includes the line 'Power abdicates only under the stress of counter-power'.[34][35]: 13 |

対抗権力 詳細は「二重権力」を参照 「対抗権力」(「対抗勢力」と表記されることもある)という用語は、被抑圧者がエリートの権力を相殺したり弱体化したりするために利用できる対抗勢力を表 現するために、さまざまな状況で用いられる。人類学者のデビッド・グレーバーは、「自治コミュニティから急進的な労働組合、民衆民兵組織に至るまで、国家 や資本に対抗する社会制度の集合体」と一般的な定義を提示している。[30] また、グレーバーはカウンターパワーは「アンチパワー」とも呼ばれることがあるとし、 「反権力」とも呼ばれ、「反権力の諸機関が国家の存在にもかかわらず存続している場合、これは通常『二重権力』の状況と呼ばれる」と指摘している。 [30] ティム・ギーは2011年の著書『Counterpower: Making Change Happen(変化を実現する)』[31] において、政府やエリート集団の権力によって力を奪われた人々がカウンターパワーを用いてこれに対抗できるという理論を提唱した。[32] ギのモデルでは、カウンターパワーは3つのカテゴリーに分けられる。すなわち、アイデア・カウンターパワー、経済的カウンターパワー、物理的カウンターパ ワーである。[31] この用語は、1990年代以降のグローバル正義/反グローバリゼーション運動の参加者によって使用されることで注目されるようになったが[33]、少なく とも60年間は使用されてきた。例えば、マーティン・ブーバーの1949年の著書『ユートピアの道』には、「権力はカウンターパワーの圧力の下でのみ退 く」という一節がある[34][35]:13 |

| Other theories Thomas Hobbes (1588–1679) defined power as a man's "present means, to obtain some future apparent good" (Leviathan, Ch. 10). The thought of Friedrich Nietzsche (1844–1900) underlies much 20th-century analysis of power. Nietzsche disseminated ideas on the "will to power", which he saw as the domination of other humans as much as the exercise of control over one's environment. Some schools of psychology, notably those associated with Alfred Adler (1870–1937), place power dynamics at the core of their theory (where orthodox Freudians might place sexuality). Paul Tillich (1886–1965) saw law as structuring/expressing power and developing through "sacramental" (community) and theocratic stages before reaching a secular rational mode.[36] Rodolfo Henrique Cerbaro suggests understanding power as "what counts as a means of determining a subject's position in a given competition".[37] |

その他の理論 トマス・ホッブズ(1588年-1679年)は、権力を「将来の見かけ上の利益を得るための現在の手段」と定義した(『リヴァイアサン』第10章)。 フリードリヒ・ニーチェ(1844年-1900年)の思想は、20世紀における権力の分析の多くに影響を与えている。ニーチェは「力への意志」という考え を広めたが、これは、環境に対する支配力を行使することと同様に、他の人間を支配することでもあると彼は考えていた。 特にアルフレッド・アドラー(1870年~1937年)に関連する心理学の学派では、権力力学を理論の中心に置いている(正統派のフロイト派であれば、性 を中心に置くであろう)。 ポール・ティリッヒ(1886年 - 1965年)は、権力は「聖礼典的」(共同体)および神政的な段階を経て世俗的な合理的な様式に到達するまで、構造化/表現され、発展すると考えた。 [36] ロドルフォ・エンリケ・セルバロは、権力を「与えられた競争における主体の位置を決定する手段として数えられるもの」と理解することを提案している。 [37] |

| Psychological research This section needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources in this section. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. (December 2023) (Learn how and when to remove this message) Recent experimental psychology suggests that the more power one has, the less one takes on the perspective of others, implying that the powerful have less empathy. Adam Galinsky, along with several coauthors, found that when those who are reminded of their powerlessness are instructed to draw Es on their forehead, they are 3 times more likely to draw them such that they are legible to others than those who are reminded of their power.[38][39] Powerful people are also more likely to take action. In one example, powerful people turned off an irritatingly close fan twice as much as less powerful people. Researchers have documented the bystander effect: they found that powerful people are three times as likely to first offer help to a "stranger in distress".[40] A study involving over 50 college students suggested that those primed to feel powerful through stating 'power words' were less susceptible to external pressure, more willing to give honest feedback, and more creative.[41] Empathy gap Main article: Empathy gap (social psychology) "Power is defined as a possibility to influence others."[42]: 1137 The use of power has evolved over centuries.[citation needed][clarification needed] Power also relates with empathy gaps because it limits the interpersonal relationship and compares the power differences. Having power or not having power can cause a number of psychological consequences. It leads to strategic versus social responsibilities.[citation needed] Research experiments were done[by whom?] as early as 1968 to explore power conflict.[42] Past research Earlier,[when?] research proposed that increased power relates to increased rewards and leads one to approach things more frequently.[citation needed] In contrast, decreased power relates to more constraint, threat and punishment which leads to inhibitions. It was concluded[by whom?] that being powerful leads one to successful outcomes, to develop negotiation strategies and to make more self-serving offers.[citation needed] Later,[when?] research proposed that differences in power lead to strategic considerations. Being strategic can also mean to defend when one is opposed or to hurt the decision-maker. It was concluded[by whom?] that facing one with more power leads to strategic consideration whereas facing one with less power leads to a social responsibility.[42] Bargaining games Bargaining games were explored[by whom?] in 2003 and 2004. These studies compared behavior done in different power given[clarification needed] situations.[42] In an ultimatum game, the person in given power offers an ultimatum and the recipient would have to accept that offer or else both the proposer and the recipient will receive no reward.[42] In a dictator game, the person in given power offers a proposal and the recipient would have to accept that offer. The recipient has no choice of rejecting the offer.[42] Conclusion The dictator game gives no power to the recipient whereas the ultimatum game gives some power to the recipient. The behavior observed was that the person offering the proposal would act less strategically than would the one offering in the ultimatum game. Self-serving also occurred and a lot of pro-social behavior was observed.[42] When the counterpart recipient is completely powerless, lack of strategy, social responsibility and moral consideration is often observed from the behavior of the proposal given (the one with the power).[42] Abusive power and control Main article: Abusive power and control See also: Coercive power One can regard power as evil or unjust; however, power can also be seen as good and as something inherited or given for exercising humanistic objectives that will help, move, and empower others as well.[citation needed] In general, power derives from the factors of interdependence between two entities and the environment.[citation needed] The use of power need not involve force or the threat of force (coercion). An example of using power without oppression is the concept "soft power" (as compared to hard power). Much of the recent sociological debate about power revolves around the issue of its means to enable – in other words, power as a means to make social actions possible as much as it may constrain or prevent them.[citation needed] Abusive power and control (or controlling behaviour or coercive control) involve the ways in which abusers gain and maintain power and control over victims for abusive purposes such as psychological, physical, sexual, or financial abuse. Such abuse can have various causes – such as personal gain, personal gratification, psychological projection, devaluation, envy or because some abusers enjoy exercising power and control. Controlling abusers may use multiple tactics to exert power and control over their victims. The tactics themselves are psychologically and sometimes physically abusive. Control may be helped through economic abuse, thus limiting the victim's actions as they may then lack the necessary resources to resist the abuse.[43] Abusers aim to control and intimidate victims or to influence them to feel that they do not have an equal voice in the relationship.[44] Manipulators and abusers may control their victims with a range of tactics, including:[45] positive reinforcement (such as praise, superficial charm, flattery, ingratiation, love bombing, smiling, gifts, attention) negative reinforcement intermittent or partial reinforcement psychological punishment (such as nagging, silent treatment, swearing, threats, intimidation, emotional blackmail, guilt trips, inattention) traumatic tactics (such as verbal abuse or explosive anger) The vulnerabilities of the victim are exploited, with those who are particularly vulnerable being most often selected as targets.[45][46][47] Traumatic bonding can occur between the abuser and victim as the result of ongoing cycles of abuse in which the intermittent reinforcement of reward and punishment fosters powerful emotional bonds that are resistant to change, as well as a climate of fear.[48] An attempt may be made to normalise, legitimise, rationalise, deny, or minimise the abusive behaviour, or to blame the victim for it.[49][50][51] Isolation, gaslighting, mind games, lying, disinformation, propaganda, destabilisation, brainwashing and divide and rule are other strategies that are often used. The victim may be plied with alcohol or drugs or deprived of sleep to help disorientate them.[52][53] Certain personality types[which?] feel particularly compelled to control other people.[citation needed] |

心理学研究 この節には検証可能な参考文献や出典が全く示されていないか、不十分です。出典を追加して記事の信頼性向上にご協力ください。 出典の無い内容は疑問視あるいは除去される場合があります。 (2023年12月) (Learn how and when to remove this message) 最近の実験心理学では、権力を持つ人ほど他者の視点に立たなくなる傾向があり、権力者は共感力が低いことを示唆している。アダム・ガリンスキーは、複数の 共著者とともに、無力感を思い起こさせるような状況にある人々に額に「Es」を描くよう指示した場合、権力者に対してそう指示した場合よりも、他人にも読 めるように「Es」を描く可能性が3倍高いことを発見した。[38][39] 権力者は行動を起こす可能性も高い。ある例では、権力者は、そうでない人よりも2倍の頻度で、煩わしいほど近くにある扇風機の電源を切っていた。研究者は 傍観者効果を記録している。権力者は「苦境にある見知らぬ他人」に最初に手を差し伸べる可能性が3倍高いことが分かっている。 50人以上の大学生を対象とした研究では、「権力的な言葉」を口にすることで権力者としての感覚を呼び覚まされた学生は、外部からの圧力に影響されにくく なり、より率直なフィードバックを好むようになり、より創造的になることが示唆された。[41] 共感のギャップ 詳細は「共感のギャップ (社会心理学)」を参照 「権力とは、他者に影響を与える可能性と定義される」[42]:1137 権力の行使は数世紀にわたって進化してきた。[要出典][要訂正] 権力は対人関係を制限し、権力差を比較するため、共感ギャップとも関連している。権力を持つこと、持たないことは、多くの心理的影響を引き起こす可能性が ある。それは戦略的責任と社会的責任の対立につながる。[要出典] 権力闘争を探求する研究実験は、早くも1968年には行われていた。[42] 過去の研究 それ以前の研究では、権力の増大は報酬の増大につながり、物事により頻繁にアプローチするようになるということが提案されていた。[要出典] これに対して、権力の減少はより多くの制約、脅威、処罰につながり、抑制につながる。 権力を持つことは成功につながり、交渉戦略を練り、より利己的な提案を行うことになるという結論が出された。[要出典] その後、[いつ?] 研究により、権力の差異は戦略的考察につながるという提案がなされた。戦略的であることは、反対された際に防御することや意思決定者を傷つけることも意味 する。より権力を持つ者と向き合うことは戦略的考察につながるが、より権力を持たない者と向き合うことは社会的責任につながるという結論が[誰によっ て?]出された。[42] 交渉ゲーム 交渉ゲームは2003年と2004年に研究された。これらの研究では、異なる権限が与えられた状況で行われた行動を比較した。[42] 最後通牒ゲームでは、権限を与えられた人物が最後通牒を提示し、受け手はその提案を受け入れなければならない。さもなければ、提案者と受け手の両方が報酬 を受け取れない。[42] 独裁者ゲームでは、権限を持つ人物が提案を行い、受領者はその提案を受け入れなければならない。受領者は提案を拒否する選択肢を持たない。[42] 結論 独裁者ゲームでは、提案を受ける側には何の権限も与えられないが、最後通牒ゲームでは、提案を受ける側にいくらか権限が与えられる。観察された行動は、提 案を行う側は、最後通牒ゲームで提案を行う側よりも戦略的に行動しないというものであった。利己的な行動も見られ、多くの社会貢献的な行動も観察された。 相手が完全に無力である場合、提案する側(権力を持つ側)の行動には、戦略の欠如、社会的責任の欠如、道徳的配慮の欠如がしばしば見られる。[42] 権力の乱用と支配 詳細は「権力の乱用と統制」を参照 関連項目「強制力 権力を悪や不正とみなすこともできるが、権力は善であり、また、人道的目標の遂行のために受け継がれたり与えられたりするものであり、他者を助け、動か し、力づけるものでもあるとみなすこともできる。一般的に、権力は2つの実体と環境との相互依存の要因から生じる。抑圧を伴わない権力の行使の例として は、「ソフトパワー」(ハードパワーに対する概念)がある。権力に関する最近の社会学的な議論の多くは、権力を行使するための手段の問題に集中している。 言い換えれば、権力は、社会的行動を制限したり妨げたりする可能性がある一方で、それを可能にする手段でもある。 権力の乱用および支配(または支配的な行動や強制的な支配)には、加害者が心理的、身体的、性的、あるいは経済的な虐待などの虐待目的のために、被害者に 対して権力と支配力を獲得し維持する方法が含まれる。このような虐待には、個人的な利益、個人的な満足感、心理的な投影、価値の低下、妬み、あるいは一部 の加害者が権力と支配力を振るうことを楽しむといった、さまざまな原因がある。 支配的な虐待者は、複数の戦術を用いて、被害者に対して権力を振るい、支配しようとする。 これらの戦術自体が心理的虐待であり、時には身体的虐待となることもある。 経済的虐待によって支配が容易になる場合もあり、被害者は虐待に抵抗するための必要な資源を欠くことになり、行動が制限されることになる。[43] 虐待者は、被害者を支配し、威嚇したり、被害者が自分には対等な発言権がないと感じるように仕向けることを目的としている。[44] 操り手や虐待者は、以下のようなさまざまな戦術を用いて被害者を支配することがある。 正の強化(賞賛、表面的な魅力、お世辞、おべっか、愛情爆弾、笑顔、贈り物、関心など 負の強化 断続的または部分的な強化 心理的罰(小言、無視、悪態、脅し、威嚇、感情的なゆすり、罪悪感、無関心など 心的外傷戦術(暴言や爆発的な怒りなど 被害者の脆弱性が利用され、特に脆弱な人々が標的に選ばれることが多い。[45][46][47] 虐待者と被害者の間に「心的外傷的結合」が起こる場合がある。これは、断続的な報酬と罰の強化が 変化に抵抗する強力な感情的な絆を育む。また、恐怖の環境も助長される。[48] 虐待的行動を正常化、正当化、合理化、否定、または最小化しようとしたり、その責任を被害者に転嫁しようとする場合もある。[49][50][51] 孤立、ガスライティング、マインドゲーム、嘘、偽情報、プロパガンダ、不安定化、洗脳、分断統治などは、よく用いられる他の戦略である。被害者を混乱させ るために、アルコールや薬物を与えたり、睡眠を奪ったりすることもある。 特定の性格タイプ[どれ?]は、特に他人を支配したいという衝動に駆られると感じている。[要出典] |

| Tactics In everyday situations people use a variety of power tactics to push or prompt other people into particular actions. Many examples exist of common power tactics employed every day. Some of these tactics include bullying, collaboration, complaining, criticizing, demanding, disengaging, evading, humor, inspiring, manipulating, negotiating, socializing, and supplicating. One can classify such power tactics along three different dimensions:[54][55] Soft and hard: Soft tactics take advantage of the relationship between the influencer and the target. They are more indirect and interpersonal (e.g., collaboration, socializing). Conversely, hard tactics are harsh, forceful, direct, and rely on concrete outcomes. However, they are not more powerful than soft tactics. In many circumstances, fear of social exclusion can be a much stronger motivator than some kind of physical punishment. Rational and nonrational: Rational tactics of influence make use of reasoning, logic, and sound judgment, whereas nonrational tactics may rely on emotionality or misinformation. Examples of each include bargaining and persuasion, and evasion and put-downs, respectively. Unilateral and bilateral: Bilateral tactics, such as collaboration and negotiation, involve reciprocity on the part of both the person influencing and their target. Unilateral tactics, on the other hand, develop without any participation on the part of the target. These tactics include disengagement and the deployment of fait accomplis. People tend to vary in their use of power tactics, with different types of people opting for different tactics. For instance, interpersonally oriented people tend to use soft and rational tactics.[54] Moreover, extroverts use a greater variety of power tactics than do introverts.[56] People will also choose different tactics based on the group situation, and based on whom they wish to influence. People also tend to shift from soft to hard tactics when they face resistance.[57][58] Balance of power Because power operates both relationally and reciprocally, sociologists speak of the "balance of power" between parties to a relationship:[59][60] all parties to all relationships have some power: the sociological examination of power concerns itself with discovering and describing the relative strengths: equal or unequal, stable or subject to periodic change. Sociologists usually analyse relationships in which the parties have relatively equal or nearly equal power in terms of constraint rather than of power.[citation needed] In this context, "power" has a connotation of unilateralism. If this were not so, then all relationships could be described in terms of "power", and its meaning would be lost. Given that power is not innate and can be granted to others, to acquire power one must possess or control a form of power currency.[61][need quotation to verify][62] Political power in authoritarian regimes In authoritarian regimes, political power is concentrated in the hands of a single leader or a small group of leaders who exercise almost complete control over the government and its institutions.[63] Because some authoritarian leaders are not elected by a majority, their main threat is that posed by the masses.[63] They often maintain their power through political control tactics like: Repression: The state targets actors who challenge their beliefs. Can be done directly or indirectly.[64] Autocrats repress actors they perceive as having irreconcilable interests, and cooperate with those they think have reconcilable ones.[65] Because of preference falsification- distinguishing between an individual's private preference and public preference- sometimes repression in itself is not enough.[66] Indoctrination: The state controls public education and uses propaganda to diffuse its views and values into society.[64] A one standard deviation increase in pro-regime propaganda reduces the odds of protest the following day by 15%.[67] Coercive distribution: The state distributes welfare and resources to keep people dependent while offering benefits to people they know they can manipulate.[64] Infiltration: The state assigns people to go into grassroot level to sway the public in favor of the authoritarian regime.[64] Although several regimes follow these general forms of control, different authoritarian sub-regime types rely on different political control tactics.[68] |

戦術 日常的な状況において、人々はさまざまな権力戦術を用いて他人をある特定の行動へと駆り立てたり、促したりする。 日常的に用いられる一般的な権力戦術の例は数多く存在する。 その中には、いじめ、協力、苦情、批判、要求、無視、回避、ユーモア、鼓舞、操作、交渉、社交、懇願などが含まれる。 このような権力戦術は、3つの異なる次元に沿って分類することができる。 ソフトとハード:ソフト戦術は影響力を持つ者とターゲットの間の関係を利用する。 それらはより間接的で対人関係的なもの(例えば、協力、社交)である。 逆に、ハード戦術は厳しく、強引で直接的であり、具体的な成果に依存する。 しかし、ソフト戦術よりも強力というわけではない。 多くの状況において、社会的排除に対する恐れは、ある種の肉体的な罰よりもはるかに強い動機付けとなりうる。 合理的および非合理的:影響力を行使する上で、合理的戦術は推論、論理、健全な判断を用いるが、非合理的戦術は感情や誤った情報に頼る可能性がある。それ ぞれを例示すると、交渉や説得、回避や中傷などがある。 一方的なもの、双方的なもの:協力や交渉といった双方的な戦術は、影響を与える側とその対象の両者による互恵性を伴う。一方、一方的な戦術は、対象者の参 加なしに展開される。このような戦術には、離脱や既成事実化がある。 人々は権力戦術の使用において異なる傾向があり、異なるタイプの人が異なる戦術を選ぶ。例えば、対人関係志向の強い人は、ソフトで理性的な戦術を用いる傾 向がある。[54] さらに、外向的な人は内向的な人よりも、より多様な権力戦術を用いる。[56] 人々はまた、グループの状況や、誰に影響を与えたいかによっても異なる戦術を選ぶ。人々はまた、抵抗に直面した場合にはソフトな戦術からハードな戦術へと 移行する傾向がある。[57][58] 力のバランス 力は相互関係的に作用するため、社会学者は関係の当事者間の「力のバランス」について語る。[59][60] すべての関係のすべての当事者は、ある程度の力を有している。力の社会学的な検証は、相対的な強さの発見と記述に関わる。すなわち、平等か不平等か、安定 しているか周期的に変化するか、といったことである。社会学者は通常、当事者が比較的同等またはほぼ同等の力を持つ関係を、力というよりも制約という観点 から分析する。[要出典] この文脈において、「力」には単独主義的な含みがある。そうでないとすれば、すべての関係は「力」という観点で説明でき、その意味は失われる。権力は生得 のものではなく、他者に付与される可能性があることを踏まえると、権力を獲得するには、何らかの権力の通貨を所有または支配していなければならない。 権威主義体制における政治権力 権威主義体制では、政治権力は単独の指導者または少数の指導者グループに集中し、彼らは政府およびその制度に対してほぼ完全な支配力を有している。 [63] 権威主義的指導者の一部は多数派によって選出されていないため、彼らにとっての主な脅威は大衆によるものである。[63] 彼らはしばしば、以下のような政治的支配の戦術によって権力を維持する。 抑圧:国家は自らの信念に異を唱えるアクターを標的にする。直接または間接的に行うことができる。[64] 独裁者は、自らの利益と相容れないとみなすアクターを弾圧し、相容れると考えるアクターと協力する。[65] 個人の私的な好みと公的な好みとを区別する好みの偽装により、抑圧自体が十分でない場合もある。[66] 教化:国家は公教育を管理し、プロパガンダを用いて自らの見解や価値観を社会に浸透させる。[64] 体制支持のプロパガンダが標準偏差で1増加すると、翌日の抗議の可能性は15%減少する。[67] 強制的な分配:国家は、人々を従属状態に保つために福祉や資源を分配する一方で、操作できるとわかっている人々には利益を提供する。[64] 浸透:国家は、草の根レベルに人々を送り込み、権威主義体制を支持するように一般市民を動かす。[64] いくつかの体制がこうした一般的な統制形態を採用しているが、異なる権威主義体制のサブタイプは、異なる政治的統制戦術に依存している。[68] |

| Effects Power changes those in the position of power and those who are targets of that power.[69] Approach/inhibition theory Developed by D. Keltner and colleagues,[70] approach/inhibition theory assumes that having power and using power alters psychological states of individuals. The theory is based on the notion that most organisms react to environmental events in two common ways. The reaction of approach is associated with action, self-promotion, seeking rewards, increased energy and movement. Inhibition, on the contrary, is associated with self-protection, avoiding threats or danger, vigilance, loss of motivation and an overall reduction in activity. Overall, approach/inhibition theory holds that power promotes approach tendencies, while a reduction in power promotes inhibition tendencies. Positive Power prompts people to take action Makes individuals more responsive to changes within a group and its environment[71] Powerful people are more proactive, more likely to speak up, make the first move, and lead negotiation[72] Powerful people are more focused on the goals appropriate in a given situation and tend to plan more task-related activities in a work setting[73] Powerful people tend to experience more positive emotions, such as happiness and satisfaction, and they smile more than low-power individuals[74] Power is associated with optimism about the future because more powerful individuals focus their attention on more positive aspects of the environment[75] People with more power tend to carry out executive cognitive functions more rapidly and successfully, including internal control mechanisms that coordinate attention, decision-making, planning, and goal-selection[76] Negative Powerful people are prone to take risky, inappropriate, or unethical decisions and often overstep their boundaries[77][78] They tend to generate negative emotional reactions in their subordinates, particularly when there is a conflict in the group[79] When individuals gain power, their self-evaluation become more positive, while their evaluations of others become more negative[80] Power tends to weaken one's social attentiveness, which leads to difficulty understanding other people's point of view[81] Powerful people also spend less time collecting and processing information about their subordinates and often perceive them in a stereotypical fashion[82] People with power tend to use more coercive tactics, increase social distance between themselves and subordinates, believe that non-powerful individuals are untrustworthy, and devalue work and ability of less powerful individuals[83] |

影響 権力は、権力を持つ者とその権力の対象となる者を変化させる。[69] 接近/抑制理論 D. Keltner 氏とその同僚によって開発された[70] 接近/抑制理論は、権力を持つこと、および権力を行使することが個人の心理状態を変えると想定している。この理論は、ほとんどの生物が環境的な出来事に対 して2つの共通した方法で反応するという考えに基づいている。接近の反応は行動、自己アピール、報酬の追求、エネルギーの増加、運動と関連している。一 方、抑制は自己防衛、脅威や危険の回避、警戒、モチベーションの喪失、活動の全般的な減少と関連している。 全体として、接近/抑制理論では、権力は接近傾向を促進し、権力の減少は抑制傾向を促進すると考えられている。 ポジティブな 権力は、人々に行動を起こさせる 個人は、グループ内およびその環境内の変化に対してより敏感になる[71] 影響力のある人はより積極的であり、発言しやすく、最初に動く傾向があり、交渉を主導する[72] 影響力のある人は、特定の状況に適した目標により集中し、職場ではより仕事に関連した活動を計画する傾向がある[73] 影響力のある人は、幸福や満足感といったポジティブな感情をより多く経験し、影響力の低い人よりも笑顔を見せる傾向がある[74] 影響力のある人は環境のポジティブな側面に意識を集中させるため、権力は未来に対する楽観主義と関連している[75] 影響力のある人は、注意、意思決定、計画、目標選択を調整する内部統制メカニズムなど、経営上の認知機能をより迅速かつ効果的に実行する傾向がある [76] ネガティブな 影響 権力者は、リスクの高い、不適切な、または非倫理的な決定を下しがちであり、しばしばその権限を越える[77][78]。 権力者は、特にグループ内で対立がある場合、部下にネガティブな感情的な反応を引き起こす傾向がある[79]。 個人が権力を得ると、自己評価はよりポジティブになり、他者に対する評価はよりネガティブになる[80]。 権力は、他者の視点の理解を困難にする傾向がある社会的注意力の低下につながる[81] 権力者はまた、部下の情報を収集し処理する時間をあまりかけず、しばしばステレオタイプな方法で部下を認識する[82] 権力を持つ人は、強制的な手段をより多く用いる傾向があり、自分と部下との間の社会的距離を広げ、権力を持たない個人は信頼できないと信じ、権力を持たな い個人の仕事や能力を軽視する傾向がある[83] |

| Reactions Tactics A number of studies demonstrate that harsh power tactics (e.g. punishment (both personal and impersonal), rule-based sanctions, and non-personal rewards) are less effective than soft tactics (expert power, referent power, and personal rewards).[84][85] It is probably because harsh tactics generate hostility, depression, fear, and anger, while soft tactics are often reciprocated with cooperation.[86] Coercive and reward power can also lead group members to lose interest in their work, while instilling a feeling of autonomy in one's subordinates can sustain their interest in work and maintain high productivity even in the absence of monitoring.[87] Coercive influence creates conflict that can disrupt entire group functioning. When disobedient group members are severely reprimanded, the rest of the group may become more disruptive and uninterested in their work, leading to negative and inappropriate activities spreading from one troubled member to the rest of the group. This effect is called Disruptive contagion or ripple effect and it is strongly manifested when reprimanded member has a high status within a group, and authority's requests are vague and ambiguous.[88] Resistance to coercive influence Coercive influence can be tolerated when the group is successful,[89] the leader is trusted, and the use of coercive tactics is justified by group norms.[90] Furthermore, coercive methods are more effective when applied frequently and consistently to punish prohibited actions.[91] However, in some cases, group members chose to resist the authority's influence. When low-power group members have a feeling of shared identity, they are more likely to form a Revolutionary Coalition, a subgroup formed within a larger group that seeks to disrupt and oppose the group's authority structure.[92] Group members are more likely to form a revolutionary coalition and resist an authority when authority lacks referent power, uses coercive methods, and asks group members to carry out unpleasant assignments. It is because these conditions create reactance, individuals strive to reassert their sense of freedom by affirming their agency for their own choices and consequences. Kelman's compliance-identification-internalization theory of conversion Herbert Kelman[93][94] identified three basic, step-like reactions that people display in response to coercive influence: compliance, identification, and internalization. This theory explains how groups convert hesitant recruits into zealous followers over time. At the stage of compliance, group members comply with authority's demands, but personally do not agree with them. If authority does not monitor the members, they will probably not obey. Identification occurs when the target of the influence admires and therefore imitates the authority, mimics authority's actions, values, characteristics, and takes on behaviours of the person with power. If prolonged and continuous, identification can lead to the final stage – internalization. When internalization occurs, individual adopts the induced behaviour because it is congruent with his/her value system. At this stage, group members no longer carry out authority orders but perform actions that are congruent with their personal beliefs and opinions. Extreme obedience often requires internalization. |

反応 戦術 多くの研究が、過酷な権力戦術(例えば、懲罰(個人および非個人)、規則に基づく制裁、非個人への報酬)は、ソフトな戦術(専門的権力、参照対象としての 権力、個人への報酬)よりも効果が低いことを示している。[84][85] 過酷な戦術は敵意、抑うつ、 一方、ソフトな戦術は往々にして協力という形で報いられる。[86] 強制力や報酬力は、グループメンバーの仕事への関心を失わせる可能性もあるが、一方で、部下に自主性を感じさせることで、監視がなくても仕事への関心を維 持し、高い生産性を維持することができる。[87] 強制的な影響力は、グループ全体の機能を混乱させる可能性のある対立を生み出す。従順でないグループメンバーが厳しく叱責されると、残りのグループメン バーはより混乱し、仕事に興味を失う可能性があり、問題を抱えるメンバーから他のグループメンバーへと、否定的で不適切な行動が広がる可能性がある。この 効果は「破壊的伝播」または「波及効果」と呼ばれ、叱責されたメンバーがグループ内で高い地位にあり、権威者の要求が曖昧で曖昧である場合に強く現れる。 強制的な影響に対する抵抗 強制的な影響は、グループが成功している場合、リーダーが信頼されている場合、強制的な戦術の使用がグループの規範によって正当化されている場合、容認さ れる可能性がある。さらに、禁止された行動を罰するために強制的な方法が頻繁かつ一貫して適用される場合、その方法はより効果的である。 しかし、場合によっては、グループのメンバーが権威の影響に抵抗することを選ぶこともある。 権威が低いグループのメンバーがアイデンティティの共有感を持っている場合、グループの権威構造を破壊し、それに反対する大規模なグループ内に形成される サブグループである革命連合を形成する可能性が高くなる。[92] 権威が参照権力を欠き、強制的な方法を用い、グループのメンバーに不快な任務を遂行するように求める場合、グループのメンバーは革命連合を形成し、権威に 抵抗する可能性が高くなる。なぜなら、これらの条件はリアクタンスを生み出すからであり、個人は、自らの選択と結果に対する自己決定を肯定することで、自 由の感覚を再主張しようとするからである。 ケルマンの服従-同一視-内面化の転換理論 ハーバート・ケルマン(Herbert Kelman)[93][94]は、強制的な影響力に対して人々が示す3つの基本的な段階的な反応、すなわち服従、同一視、内面化を特定した。この理論 は、グループが時間をかけてためらいがちな新入者を熱心な信奉者に変える方法を説明するものである。 服従の段階では、グループのメンバーは権威者の要求に従うが、個人的にはそれに同意していない。権威者がメンバーを監視していない場合、おそらく彼らは従 わないだろう。 影響を受ける対象が権威者を賞賛し、権威者の行動、価値観、特徴を模倣し、権力者の行動様式を身につけると、同一化が起こる。同一化が長期にわたって継続 すると、最終段階である内面化につながる可能性がある。 内面化が起こると、その行動が個人の価値観と一致するため、個人はその行動を自ら取り入れるようになる。この段階では、グループのメンバーはもはや権威の 命令に従うのではなく、自分自身の信念や意見と一致する行動を取るようになる。極端な服従には、内面化が必要な場合が多い。 |

| Power literacy Power literacy refers to how one perceives power, how it is formed and accumulates, and the structures that support it and who is in control of it. Education[95][96] can be helpful for heightening power literacy. In a 2014 TED talk Eric Liu notes that "we don't like to talk about power" as "we find it scary" and "somehow evil" with it having a "negative moral valence" and states that the pervasiveness of power illiteracy causes a concentration of knowledge, understanding and clout.[97] Joe L. Kincheloe describes a "cyber-literacy of power" that is concerned with the forces that shape knowledge production and the construction and transmission of meaning, being more about engaging knowledge than "mastering" information, and a "cyber-power literacy" that is focused on transformative knowledge production and new modes of accountability.[98] |

パワーリテラシー パワーリテラシーとは、権力をどう認識するか、それがどのように形成され蓄積されるか、それを支える構造、そしてそれを誰が支配しているか、ということで ある。教育[95][96]は、パワーリテラシーを高めるのに役立つ。2014年のTEDトークで、エリック・リューは「私たちは権力について語りたがら ない」と指摘している。それは「怖い」し、「どこか邪悪」で、「否定的な道徳的価値」があるからであり、権力に関する無知が蔓延しているために、知識、理 解、影響力が集中してしまうと述べている。 ジョー・L・キンチローは、知識の生産や意味の構築と伝達を形作る力に関わる「サイバー・リテラシー・オブ・パワー」について説明している。これは、情報 を「習得」することよりも、知識を積極的に活用することに重点を置いている。また、「サイバー・パワー・リテラシー」は、変革的な知識の生産と新たな説明 責任のあり方に焦点を当てている。[98] |

| Acquiescence Amity-enmity complex Authority bias Control of time in power relationships Discourse of power Discipline Entitlement Power structure Power vacuum Separation of powers Speaking truth to power Social control Social norm State collapse The Anatomy of Revolution Veto, the power to forbid an action |

黙認 友好と敵対の複雑な関係 権威への偏見 権力関係における時間のコントロール 権力に関する言説 規律 権利付与 権力構造 権力の空白 権力の分立 権力に真実を語る 社会的統制 社会的規範 国家の崩壊 革命の構造 拒否権、行動を禁止する権限 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Power_(social_and_political) |

★リンク

★文献

★その他の情報

【余滴】

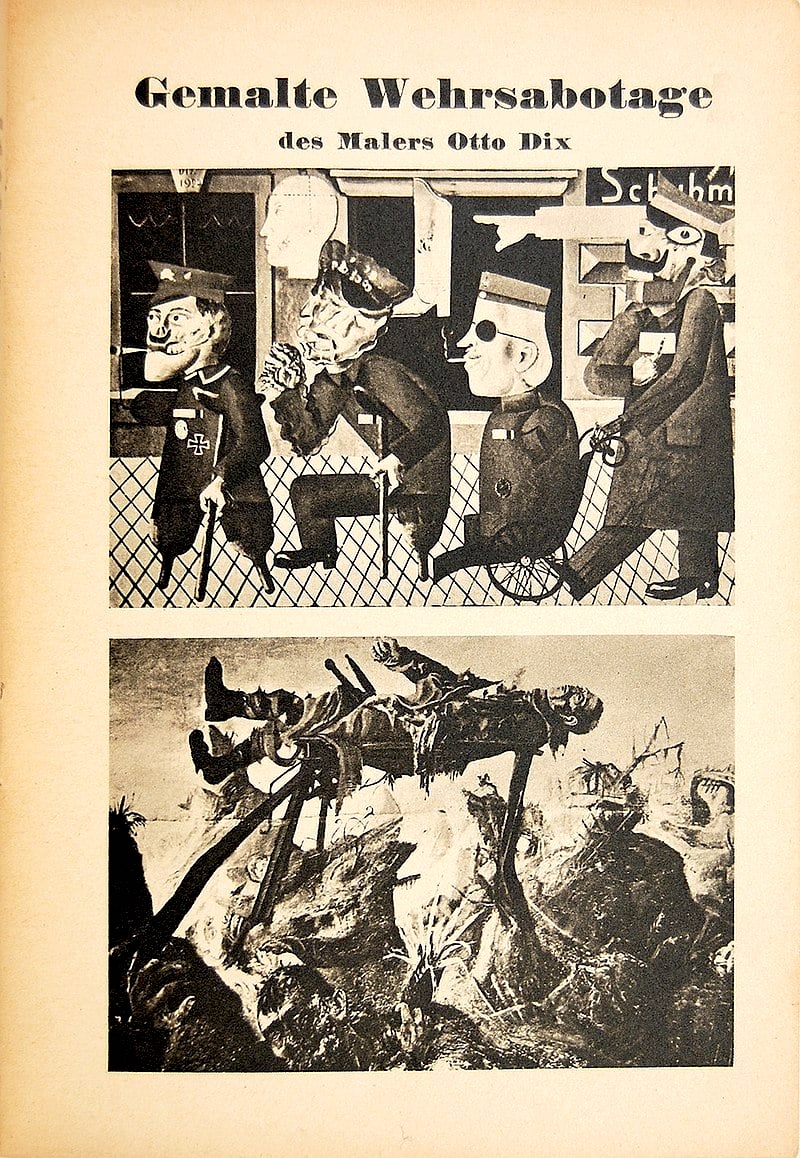

| “Painted sabotage of Otto Dix.” Page from the programme (Ausstellungsführer) for "Degenerate Art", an art exhibition first shown in München 1937. The visitor's guide was written by Fritz Kaiser and published by Verlag für Kultur- und Wirtschaftswerbung for the Amtsleitung Kultur of the Reichspropagandaleitung der NSDAP, the Nazi Party's propaganda central office in Germany 1926–1945. The brochure was published in 1938 when the exhibition went on tour to Berlin (shown in Kunsthalle Berlin from 26 February to 8 May) and other cities until 1941. No known copyright restrictions. The Degenerate Art Exhibition (German: Die Ausstellung "Entartete Kunst") was organized by Adolf Ziegler and the Nazi Party in Munich from 19 July to 30 November 1937. The exhibition presented 650 works of art, confiscated from German museums, and was staged in counterpoint to the concurrent Great German Art Exhibition. Degenerate art was defined as works that "insult German feeling, or destroy or confuse natural form or simply reveal an absence of adequate manual and artistic skill". Another Degenerate Art Exhibition was hosted a few months later in Berlin, and later in Leipzig, Düsseldorf, Weimar, Halle, Vienna and Salzburg, to be seen by another million or so people. | オットー・ディックスの絵画による破壊工作。1937年にミュンヘンで

初公開された美術展「退廃芸術」のプログラム(展示ガイド)の一ページ。この展示ガイドはフリッツ・カイザーが執筆し、文化・経済宣伝出版社

(Verlag für Kultur- und

Wirtschaftswerbung)が発行した。発行元はナチス党宣伝中央局(Reichspropagandaleitung der

NSDAP)文化局(Amtsleitung

Kultur)である。同局は1926年から1945年までドイツで活動した。このパンフレットは、展覧会がベルリン(1938年2月26日~5月8日、

ベルリン美術館にて開催)やその他の都市を巡回した1938年に出版された。著作権上の制限は確認されていない。「退廃芸術展」(ドイツ語:Die

Ausstellung 「Entartete

Kunst」)は、アドルフ・ツィーグラーとナチス党によって1937年7月19日から11月30日までミュンヘンで開催された。本展ではドイツの美術館

から没収された650点の芸術作品が展示され、同時開催の「大ドイツ芸術展」に対抗する形で企画された。退廃芸術とは「ドイツ的感情を侮辱する、あるいは

自然の形態を破壊・混乱させる、あるいは単に十分な手技的・芸術的技能の欠如を露呈する」作品と定義された。数か月後にはベルリンで、その後ライプツィ

ヒ、デュッセルドルフ、ワイマール、ハレ、ウィーン、ザルツブルクでも同様の退廃芸術展が開催され、さらに約100万人がこれを目にした。 |

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

Copyleft,

CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099