Ultra-Enlightment Ideology

| 1.【能力】世界を把握する感性 |

| 2.【感性】自己の達成と失敗を受け 止める感性 |

| 3.【能力】物事を理解して、大切な 事とそうでないことを識別する能力 |

| 4.【感性】事物のリアリティを受け 取る感性 |

| 5.【能力】コミットメントできる能 力 |

☆イマヌエル・カントの文章「啓蒙とはなに

か」は啓蒙主義の重要な宣言である。その中で彼は、人間が偏見の闇から抜け出すため

に、自らの努力によって理性の光を得るにはどうすればよいかを問うている。その答えは、自分自身の

理性を使うことにある(→「理性の公的使用」)。

この文章でカントは、人が偏見を持たずに主体的に考えることがいかに重要であるかを書いている。そのために彼は、ローマの詩人ホラティウス(Horace)から借用した格言

「Sapere aude! (あえて知れ!)」という格言を用いている(→「未成年状態からの脱却」)。

カントはこの格言をクリスチャン・ヴォルフの

独断的な形而上学と共有しているが、それはすべての哲学を特徴づける理性への一般的な努力の表現であるため、そうでなければカントの批判の対象となる(→

「カント流の批判」)。形

而上学的な独断主義は、自らの力に依存する理性の幻想であり、哲学的である合理主義的な幻想である。一方、熱狂と神秘主義は理性の放棄である。

再掲:シン啓蒙理性を考える5つの柱

1.【能力】世界を把握する感性

2.【感性】自己の達成と失敗を受け止める感性

3.【能力】物事を理解して、大切な事とそうでないことを識別する能力

4.【感性】事物のリアリティを受け取る感性

5.【能力】コミットメントできる能力

●イマヌエル・カント「啓蒙とはなにか?」

1)啓蒙の定義:人間が自ら招いた未熟(=未成年の状態)の状態から抜け出ること

2)未熟(= 未成年の状態)の利点:他人に依存するのでとっても便利、だって人に頼ればいいんだもーん。カントはセクシストだから、男性の未成年者と女性は、このよう な状態に甘んじたままだと批判

3)未熟から 抜け出せない理由:上掲のごとく楽チンだからである

4)公衆の啓蒙:個人が未熟状態から脱するのは困難だが公衆はそうでもない。公衆に自由を与え れば、未熟から脱出しようとするからだ。革命は便利だが、革命に自ら委ねるだけではダメ。大衆に埋没してしまう

5)理性の公的利用、理性の私的利用:公衆が未熟から脱出するためには公衆に自由を与えればよ い。理性の公的な利用は学者(おつむの賢いひと)がみんなの前で、理性を使ってみせることである。理性の私的利用とは、個人が理性を使うことである。

6)3つの事例:戦時に上官の命令に従う、市民として納税する。牧師が信徒の前で説教すること は理性を使わないが、牧師が市民の前で公にはなすことは理性をつかう。

7)宗教家は、人間の自由をさまたげることを、市民の前で話してはならない。認識を拡張し、誤 りを取り除くき、一般に啓蒙することを禁じたら、それは人間性に対する犯罪である。国民と法の関係については、国民の間で法についての話し合うことで、法 が自由を制限してはならないことに気づくはずだ。あらゆる宗教は、人間の自由を妨げてはならない。

8)君主が法律を定めることができるのは、君主が国民の総意にある時にである。日本は象徴天皇 制なので國民の総意を代表して議会が立法し政府がそれを実行しなきゃならない.つまり國民の総意を反映していない國葬儀をおこなうことは違憲なのだ。

9)カントが「啓蒙とはなにか」を書いたフリードリッヒ大王の世紀は、啓蒙された時代だろう か?とカントは問う。カントの答えは「そうではないが、啓蒙されつつある時代」だと診断する。つまり、今の時代は「啓蒙の時代」だ。カントは、理想的な啓 蒙時代の君主像を提示する。

10)啓蒙の広がり、カントは、フ リードリッヒ大王の世紀を一生懸命用語するが、とりわけ、宗教界への自由の抑圧を批判するために、啓蒙君主をよい しょする戦略をとっているかのようだ。

11)啓蒙は、かくのごとく、人間の自由の不可分でこのましいものだが、それを遂行するために は、啓蒙君主のもとで自由を享受する臣民には、次のようなことが言われなければならない:「好きなだけ、何事についても議論しなさい、ただし(君主に)服 従せよ」。そのような逆説が、共和状態の市民の自由には課される。また、精神を多少なりとも制約するほうが精神の自由についてのその能力を発揮するような 自由の余地がうまれる。これもまた、啓蒙の逆説である。自由に行動する能力が高まると、統治の原則にまでおよんでゆく。統治者はもはや機械ではない、人間 (市民)をそれにふさわしく処遇することが、自らにとっても有益であることを理解するようになる。

《啓蒙とはなにか?》

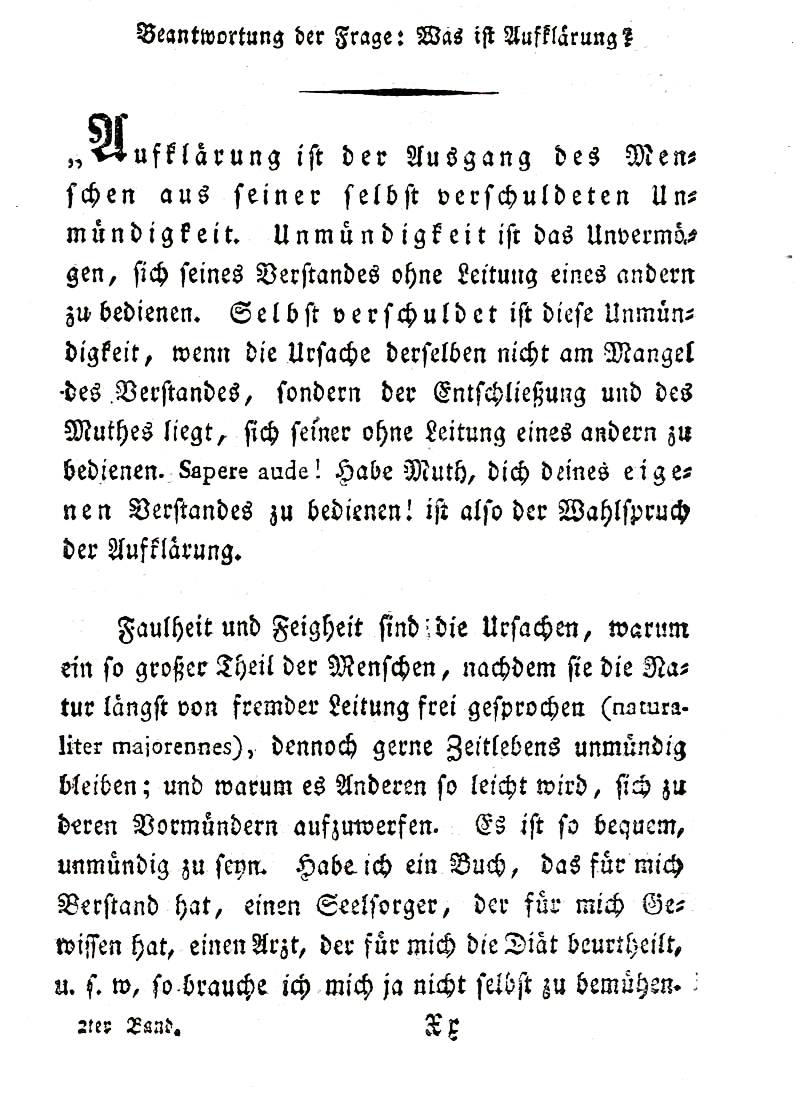

The first page of the 1799 edition

☆カントのいう「未成年状態」のなかに

は、カテゴリーとしては、それ以外に、女性、子ども、少数民族、未開人(野蛮人)、さらには動物なども含まれていただろう(→「カントとレイシズム」)。

| Beantwortung

der Frage: Was ist Aufklärung?

ist ein Essay des Philosophen Immanuel Kant aus dem Jahr 1784. In

seinem in der Berlinischen Monatsschrift veröffentlichten Beitrag ging

er auf die Frage des Pfarrers Johann Friedrich Zöllner „Was ist

Aufklärung?“ ein, die dieser ein Jahr zuvor in derselben Zeitung

gestellt hatte. Kant lieferte in dem Text seine bis heute klassische

Definition der Aufklärung. |

1784年、哲学者イマヌエル・カントが『Berlinische

Monatsschrift』誌に発表した論文『啓蒙とは何か』は、その1年前に同紙に掲載された牧師ヨハン・フリードリヒ・ツェルナーによる「啓蒙とは

何か」という問いに答えたものである。その中でカントは、今日に至るまで古典的な啓蒙主義の定義を述べている。 |

| Einführung Kants Text ist ein bedeutendes Manifest der Aufklärung. Darin fragt er, wie der Mensch aus eigener Kraft Zugang zum Licht der Vernunft erlangen kann, um aus dem Dunkel der Vorurteile herauszutreten. Die Antwort liegt dabei im Gebrauch des eigenen Verstandes.[1] Kant schreibt in diesem Text, wie wichtig es für den Menschen ist, selbständig und ohne Vorurteile zu denken. Dazu bedient er sich der dem römischen Dichter Horaz entlehnten Maxime „Sapere aude!“ (Wage zu wissen!). Diese Maxime teilt Kant mit der dogmatischen Metaphysik Christian Wolffs, die ansonsten Gegenstand der kantischen Kritik ist, weil sie Ausdruck eines allgemeinen Strebens nach Vernunft ist, welches alle Philosophie als solche charakterisiert.[2] Der metaphysische Dogmatismus ist dabei die Illusion einer Vernunft, die auf ihre eigene Kraft setzt, eine rationalistische Illusion, die aber philosophisch ist, während Schwärmerei und Mystik ein Verzicht auf die Vernunft sind.[3] |

はじめに カントの文章は啓蒙主義の重要な宣言である。その中で彼は、人間が偏見の闇から抜け出すために、自らの努力によって理性の光を得るにはどうすればよいかを 問うている。その答えは、自分自身の理性を使うことにある[1]。 この文章でカントは、人が偏見を持たずに主体的に考えることがいかに重要であるかを書いている。そのために彼は、ローマの詩人ホレスから借用した格言 「Sapere aude! (あえて知れ!)」という格言を用いている。 カントはこの格言をクリスチャン・ヴォルフの独断的な形而上学と共有しているが、それはすべての哲学を特徴づける理性への一般的な努力の表現であるため、 そうでなければカントの批判の対象となる[2]。 形而上学的な独断主義は、自らの力に依存する理性の幻想であり、哲学的である合理主義的な幻想である。一方、熱狂と神秘主義は理性の放棄である[3]。 |

| Textgeschichte In der Septemberausgabe der Zeitschrift Berlinische Monatsschrift von 1783 erschien ein anonym mit „E. v. K.“ gezeichneter Beitrag des Mitherausgebers Johann Erich Biester mit dem von anderen als ketzerisch empfundenen Titel Vorschlag, die Geistlichen nicht mehr bei Vollziehung der Ehen zu bemühen.[4] Dieser stand am Beginn der so genannten Aufklärungsdebatte, die sich als äußerst folgenreich und fruchtbar für die Geschichte der Philosophie erwies, besonders in Preußen. In der Dezemberausgabe des gleichen Jahres veröffentlichte der protestantische Berliner Pfarrer Johann Friedrich Zöllner seine Replik Ist es rathsam, das Ehebündniß nicht ferner durch die Religion zu sanciren? In einer Fußnote stellte er die provozierende Frage: „Was ist Aufklärung?“[5] Zöllner spielte mit der Frage auf die Tatsache an, dass es noch keine eindeutige Definition der Bewegung gab, obwohl diese schon seit Jahrzehnten bestand. In der Septemberausgabe von 1784 veröffentlichte der Philosoph Moses Mendelssohn als seine Antwort einen Aufsatz mit dem Titel Ueber die Frage: was heißt aufklären?[6] In der Dezemberausgabe erschien dann der Aufsatz von Immanuel Kant.[7] In einer später hinzugefügten Anmerkung am Schluss schreibt Kant, dass ihm der Aufsatz von Moses Mendelssohn noch nicht bekannt war und er ansonsten den seinigen zurückgehalten hätte. |

テキストの歴史 雑誌『Berlinische Monatsschrift』の1783年9月号に、共同編集者のヨハン・エーリッヒ・ビースターによって「E. v. K.」と署名された匿名の論文が発表された。 同年12月号には、ベルリンのプロテスタントの牧師ヨハン・フリードリヒ・ツェルナーが、その反論Ist es rathsam, das Ehebündniss nicht ferner durch die Religion zu sanciren? 脚注の中で、彼は「啓蒙とは何か」という挑発的な問いを投げかけた[5]。ツェルナーの問いは、啓蒙運動がすでに何十年も存在していたにもかかわらず、そ の明確な定義がまだなかったという事実を暗示していた。 1784年9月号では、哲学者モーゼス・メンデルスゾーンが、Ueber die Frage: what heißt aufklären? と題するエッセイでその答えを発表した[6]。その後、イマヌエル・カントのエッセイが12月号に掲載された[7]。 |

| Inhalt Sapere aude! - Wage zu wissen!  Kants Text zählt zu den bekanntesten Schriften der deutschsprachigen Aufklärung Kant beginnt seinen Aufsatz unmittelbar mit der berühmten Definition: „Aufklärung ist der Ausgang des Menschen aus seiner selbstverschuldeten Unmündigkeit.“ Im Folgenden werden diese Begriffe erläutert: Unmündigkeit sei das „Unvermögen sich seines Verstandes ohne die Leitung eines anderen zu bedienen“. Diese Unmündigkeit sei selbstverschuldet, wenn ihr Grund nicht ein Mangel an Verstand sei, sondern die Angst davor, sich seines eigenen Verstandes ohne die Anleitung eines anderen zu bedienen. Daraufhin formuliert Kant den Wahlspruch der Aufklärung: „Sapere aude!“, was etwa bedeutet „Wage zu wissen!“ und von Kant mit „Habe den Mut, dich deines eigenen Verstandes zu bedienen!“ erläutert wird. Mündigkeit und Unmündigkeit In dem nun folgenden Absatz führt Kant den Gegensatz zwischen Mündigkeit und Unmündigkeit ein. Mündigkeit bedeutet für Kant dabei, selbstständig zu denken bzw. jederzeit den Mut zu haben, sich seines eigenen Verstandes zu bedienen. Dann erklärt er, warum ein großer Teil der Menschen, obwohl sie längst erwachsen sind und fähig wären, selbst zu denken, zeit ihres Lebens unmündig bleiben, das heißt nicht selbstständig denken und dies auch noch gerne tun. Der Grund dafür sei „Faulheit und Feigheit“. Denn es sei bequem, unmündig zu sein. Das „verdrießliche Geschäft“ des eigenständigen Denkens könne leicht auf andere übertragen werden. Wer einen Arzt habe, müsse seine Diät nicht selbst beurteilen; anstatt sich selbst Wissen anzueignen, könne man sich auch einfach Bücher kaufen; wer sich einen „Seelsorger“ leisten könne, brauche selbst kein Gewissen. Somit sei es nicht nötig, selbst zu denken, und der Großteil der Menschen („darunter das ganze schöne Geschlecht“) mache von dieser Möglichkeit Gebrauch. So werde es für andere leicht, sich zu den „Vormündern“ dieser Menschen aufzuschwingen. Diese Vormünder sorgten auch dafür, dass die „unmündigen“ Menschen „den Schritt zu Mündigkeit“ außer für beschwerlich auch noch für gefährlich hielten. Kant vergleicht hier die unaufgeklärten Menschen mit „Hausvieh“, das dumm gemacht worden sei. Sie würden eingesperrt in einen „Gängelwagen“. Ihnen würden von ihren Vormündern stets die Gefahren gezeigt, die ihnen drohten, wenn sie versuchten, selbstständig zu handeln. So werde es für jeden einzelnen Menschen schwer, sich allein aus der Unmündigkeit zu befreien – zum einen, weil er sie „liebgewonnen“ habe, weil sie bequem sei, und zum anderen, weil er inzwischen größtenteils wirklich unfähig sei, sich seines eigenen Verstandes zu bedienen, weil man ihn nie den Versuch dazu habe machen lassen und ihn davon abgeschreckt habe. Die einzige Möglichkeit, einem Menschen das Denken beizubringen, besteht Kants Meinung nach darin, ihn es selbst versuchen zu lassen. |

目次 Sapere aude!- 知る勇気を持て  カントの文章は、ドイツ語圏の啓蒙主義における最も有名な著作のひとつである。 カントは有名な定義から直接エッセイを始める: 「啓蒙とは、人間が自らに課した未熟さから抜け出すことである。 未熟とは、「他者の導きなしに自分の知性を使うことができない」ことである。その原因が理解力の欠如ではなく、他者の導きなしに自分の理解力を使うことへ の恐れであるならば、この未熟さは自業自得である。 カントは、啓蒙主義のモットーである 「Sapere aude!」を定式化した。「Sapere aude!」とは、大まかに言えば「知る勇気を持て!」という意味であり、カントは「自分の理解を使う勇気を持て!」と説明している。 成熟と未熟 次の段落で、カントは成熟と未熟の対比を紹介している。カントにとって成熟とは、自分の頭で考えることができること、あるいは常に自分の知性を使う勇気を 持つことである。そして、成長して久しく、自分の頭で考えることができるにもかかわらず、なぜ多くの人々が生涯未熟なままなのか、つまり自分の頭で考え ず、そうすることに喜びを感じているのかを説明する。 その理由は「怠惰と臆病」である。未熟であることが心地よいからだ。自分で考えるという 「迷惑な仕事 」は、簡単に他人に転嫁できる。医者がいれば、自分で食事を判断する必要はない。自分で知識を得る代わりに、本を買えばいいだけだ。「カウンセラー」を雇 う余裕があれば、自分で良心を持つ必要はない。したがって、自分の頭で考える必要はなく、大多数の人々(「より公平な性別も含めて」)がこの選択肢を利用 している。そのため、他人がこうした人々の「後見人」になることは容易である。 これらの保護者はまた、「未熟な」人々が「成熟への一歩」を困難であるだけでなく危険であると考えるようにした。カントは啓蒙されていない人々を、愚かに された「家畜」に例えている。彼らは「ゲンゲルヴァーゲン」に閉じ込められた。保護者たちは、彼らが独自に行動しようとすれば危険であることを常に示し た。このため、各個人が未熟さから解放されるのは難しい。第一に、それが快適であるために「好きになって」しまったからであり、第二に、彼らのほとんど は、やってみることを許されず、そうすることを思いとどまらされてきたために、自分の心を使うことが本当にできなくなってしまったからである。カントの考 えでは、人に考えることを教える唯一の方法は、自分でやってみせることである。 |

| Sozialer Druck, nicht zu denken Kant beseitigt allerdings die Frage des sozialen Drucks nicht. Er ist insofern mächtig, als er Menschen, die eigenständig denken wollen, dazu verleitet, sich der Gruppe der unmündigen Erwachsenen zu unterwerfen. Dies sei schädlich, denn in jeder Gruppe „werden sich immer einige Selbstdenkende [...] finden, welche, nachdem sie das Joch der Unmündigkeit selbst abgeworfen haben, den Geist einer vernünftigen Schätzung des eigenen Werts und des Berufs jedes Menschen, selbst zu denken, um sich verbreiten werden.“ Die Öffentlichkeit, die nicht in der Lage ist, die aufgeklärten Menschen zu erreichen, versucht oft, „sie hernach zu zwingen, darunter zu bleiben“. Aufklärung der Gesamtöffentlichkeit Daraufhin behandelt Kant die Aufklärung des Einzelnen im Vergleich zur Gesamtöffentlichkeit. Wegen der vorher beschriebenen Zustände habe der einzelne Mensch nur geringe Möglichkeiten, sich selbst aufzuklären. Wahrscheinlicher sei es, dass sich ein „Publikum“ aufkläre, also im Gegensatz zum Individuum die gesamte Gesellschaft eines Staates oder große Teile davon. Denn unter der Vielzahl der unmündigen Bürger fänden sich immer ein paar „Selbstdenkende“. Als Vorbedingung fordert Kant Freiheit. Unter dieser Voraussetzung erscheint ihm die Aufklärung der Öffentlichkeit „beinahe unausbleiblich“. Dagegen werde eine Revolution nie eine „wahre Reform der Denkungsart“ herbeiführen, „sondern neue Vorurtheile werden (...) zum Leitbande des gedankenlosen großen Haufens dienen.“ Öffentlicher und privater Vernunftgebrauch Kant unterscheidet im Folgenden zwei Verwendungszwecke von Vernunft und Sprache, nämlich den öffentlichen Gebrauch und den privaten Gebrauch. Der öffentliche Gebrauch der Vernunft sei derjenige, den jemand als Privatmann mache, also z. B. als Gelehrter vor seinem Lesepublikum. Im Gegensatz dazu steht der „Privatgebrauch“ der Vernunft. Dies sei derjenige Gebrauch von der Vernunft, den jemand als Inhaber eines öffentlichen Amtes mache, z. B. als Offizier oder als Beamter. Er ist zum Gehorsam verpflichtet, und in seiner Freiheit eingeschränkt, weil er eine Organisation vertritt. Der öffentliche Gebrauch der Vernunft beinhaltet hingegen die Redefreiheit, das Recht der freien Meinungsäußerung in Rede und Schrift. Er muss, so Kant, „jederzeit frei sein“. Dagegen könne (und müsse auch teilweise) der Privatgebrauch der Vernunft „öfters sehr enge eingeschränkt sein“. Dies sei der Aufklärung nicht weiter hinderlich. Die von Kant als notwendige Voraussetzung der Aufklärung geforderte Freiheit ist das Recht, von seiner Vernunft in allen Bereichen „öffentlichen Gebrauch zu machen“. Zur Erklärung führt Kant folgendes Beispiel an: Wenn ein Offizier im Kriegsdienst von seinen Vorgesetzten einen Befehl erhalte, dürfe er nicht im Dienst über die Zweckmäßigkeit oder Nützlichkeit dieses Befehls räsonieren, sondern müsse gehorchen. Allerdings könne ihm später nicht verwehrt werden, über die Fehler im Kriegsdienst zu schreiben und dies dann seinem Lesepublikum zur Bewertung vorzulegen. Amtsträger, aber auch die einzelnen Bürger, sind demnach im Bereich ihres Amtes bzw. ihrer staatsbürgerlichen Pflichten, z. B. beim Zahlen von Abgaben, zu Gehorsam verpflichtet, um die Ordnung und die Sicherheit des Staates und seiner Institutionen zu gewährleisten. Dadurch aber, dass sie als Gelehrte öffentlich von ihrer Vernunft Gebrauch machen können, ergibt sich die Möglichkeit der öffentlichen wissenschaftlichen Diskussion der Verhältnisse im Staat. Auf diesem Weg kann der Monarch zur Einsicht und zur Änderung der Verhältnisse bewegt werden. So können also nach Kant Reformen erreicht werden. |

考えるなという社会的圧力 しかし、カントは社会的圧力の問題を排除していない。社会的圧力は、自分の頭で考えようとする人々を、未成年の大人たちの集団に従わせようとする限りにお いて強力である。これは有害である。なぜなら、どんな集団の中にも、「未熟さというくびきを自ら投げ捨て、自分自身の価値と、すべての人が自分の頭で考え るという職業を合理的に評価する精神を周囲に広める、独立した思想家[...]が必ず存在する 」からである。啓蒙された人々に到達できない大衆は、しばしば「その下に留まらせようとする」。 大衆全体の啓蒙 次にカントは、大衆全体と比較して、個人の啓蒙について論じる。上述したような状況のため、個人が自らを啓発する機会はほとんどない。それよりも「公」の 方が、つまり個人とは対照的に、国家の社会全体やその大部分を啓発する可能性が高い。多数の未熟な市民の中には、常に少数の「自己思考者」が存在するから である。カントは前提として自由を要求する。この条件のもとでは、大衆の啓蒙は彼にとって「ほとんど必然的」であるように思われる。他方、革命が「考え方 の真の改革」をもたらすことはなく、「新しい偏見が(中略)思慮のない大衆の指導原理となる」のである。 理性の公的利用(→公共的理性)と私的利用 以下、カントは理性と言語の二つの使用、すなわち公的使用と私的使用を区別する。理性の公的な使用とは、誰かが私的な個人として行うものであり、例えば、 読者という聴衆の前で学者として行うものである。これとは対照的なのが、理性の「私的使用」である。これは、誰かが公職、例えば役員や公務員として行う理 性の使用である。彼は組織の代表であるため、従う義務があり、自由が制限されている。一方、理性の公的利用には、言論の自由、つまり言論や文章で自由に意 見を述べる権利が含まれる。カントによれば、これは「常に自由でなければならない」。他方、理性の私的利用は「しばしば非常に厳しく制限される」ことがあ る(時にはそうしなければならない)。これは啓蒙の妨げにはならない。啓蒙の必要条件としてカントが要求する自由とは、あらゆる領域で自分の理性を「公に 利用する」権利である。 カントはこれを説明するために次のような例を挙げている: 軍務に就いている将校が上官から命令を受けた場合、任務中にその命令の便宜性や有用性について理性を働かせることは許されず、従わなければならない。しか し、後日、軍務での過ちについて文章を書き、それを読者に提示して評価される権利は否定されない。 したがって、公務員だけでなく、個々の市民も、国家とその機関の秩序と安全を確保するために、その職務の領域や市民的義務、たとえば納税の際には服従する 義務がある。しかし、学者として公的に理性を行使できるということは、国家の状況を公的に学術的に論じる機会があるということである。そうすることで、君 主に状況を認識させ、変えるよう説得することができる。カントによれば、こうして改革が達成されるのである。 |

| Politik und Freiheit Dem freien Denken sollte kein Hindernis im Wege stehen. Eine doktrinäre Gruppe, wie eine Kirchenversammlung, hat kein Recht, nachfolgenden Generationen den Gehorsam gegenüber bestimmten Dogmen aufzuzwingen - jede Generation muss hinterfragen, was ihr überliefert wurde. Kant geht dann ganz allgemein auf das Denkverbot auf der politischen Ebene ein: „Was aber nicht einmal ein Volk über sich selbst beschließen darf, das darf noch weniger ein Monarch über das Volk beschließen; denn sein gesetzgebendes Ansehen beruht eben darauf, daß er den gesamten Volkswillen in dem seinigen vereinigt.“ Der Monarch entwertet sich selbst, wenn er versucht zu regeln, welche Schriften erlaubt und verboten sind, was Kant zu einem lateinischen Zitat veranlasst: Caesar non supra grammaticos. - Der Kaiser steht nicht über den Grammatikern. Die Frage „Leben wir jetzt in einem aufgeklärten Zeitalter?“ verneint Kant, aber man lebe in einem Zeitalter der Aufklärung. Besonders in „Religionsdingen“ seien die meisten Menschen noch sehr weit davon entfernt, sich selbst ihres Verstandes ohne fremde Leitung zu bedienen. Allerdings gebe es doch auch deutliche Anzeichen dafür, dass die allgemeine Aufklärung voranschreite. Die besten Monarchen seien dabei diejenigen wie Friedrich II., der „es für Pflicht halte, in Religionsdingen den Menschen nichts vorzuschreiben“. Die Erfahrung Friedrichs II. zeigt dabei, so Kant, dass in einem freiheitlichen Regime nichts zu befürchten sei „für die öffentliche Ruhe und Einigkeit des gemeinen Wesen“. Kant kommt zu dem Schluss, dass die Ausweitung der Aufklärung dazu führe, den Menschen als ein vernünftiges Wesen „der nun mehr als Maschine ist, seiner Würde gemäß zu behandeln“. |

政治と自由(→価値自由) 自由な思想を阻むものはあってはならない。教会の集会のような教条主義的な集団には、特定の教義への服従を後世に押し付ける権利はない。カントは次に、政 治レベルにおける思想の禁止について、一般的な用語で次のように述べる。「しかし、人民でさえそれ自身について決定することができないことは、君主であっ ても人民について決定することはできない。君主は、どの文章が許され、どの文章が禁じられているかを規制しようとするとき、君主自身を軽んじることにな る: カエサルは文法の上に立つ者ではない。- 皇帝は文法家の上にいるのではない。 カントは「我々は今、啓蒙の時代に生きているのか」という問いに否定的に答えているが、我々は啓蒙の時代に生きている。特に「宗教の問題」においては、ほ とんどの人が外部からの指導なしに自分の知性を使えるようになるには、まだほど遠い。しかし、一般的な啓蒙が進んでいることを示す明確な兆候もある。最も 優れた君主は、「宗教の問題で人々に指図しないことを自分の義務と考えた」フリードリヒ2世のような君主であった。カントによれば、フリードリヒ2世の経 験は、自由主義的な体制においては「公共の平和と共通の存在の統一にとって」恐れることは何もないことを示している。 カントは、啓蒙主義の拡大が、人間を理性的存在として「今や機械以上の存在であり、その尊厳に従って扱われるべきもの」へと導くという結論に達した。 |

| Zitate „Aufklärung ist der Ausgang des Menschen aus seiner selbstverschuldeten Unmündigkeit. Unmündigkeit ist das Unvermögen, sich seines Verstandes ohne Leitung eines anderen zu bedienen. Selbstverschuldet ist diese Unmündigkeit, wenn die Ursache derselben nicht am Mangel des Verstandes, sondern der Entschließung und des Muthes liegt, sich seiner ohne Leitung eines anderen zu bedienen. Sapere aude! Habe Muth, dich deines eigenen Verstandes zu bedienen! ist also der Wahlspruch der Aufklärung.“ „Daß der bei weitem größte Teil der Menschen (darunter das ganze schöne Geschlecht) den Schritt zur Mündigkeit, außer dem daß er beschwerlich ist, auch für sehr gefährlich halte: dafür sorgen schon jene Vormünder, die die Oberaufsicht über sie gütigst auf sich genommen haben.“ |

引用 「悟りとは、人間が自ら招いた未熟さから抜け出すことである。未熟さとは、他者の導きなしに自分の知性を使いこなせないことである。この未熟さの原因が理 解力の欠如にあるのではなく、他者の導きなしにそれを活用する決意と勇気の欠如にあるのであれば、この未熟さは自業自得である。Sapere aude!それゆえ、啓蒙主義のモットーである。 「(公正な性全体を含む)人間の大部分は、成熟へのステップが困難であるという事実とは別に、非常に危険であると考えている。 |

| Rezeption Diesem Artikel fehlen noch folgende wichtige Informationen: Rezeption und Wirkungsgeschichte des Textes wäre wünschenswert. Hilf der Wikipedia, indem du sie recherchierst und einfügst. „Was ist Aufklärung“ gilt als eines der bedeutendsten Werke Immanuel Kants.[8] Sein Exordium zählt zu den berühmtesten Sätzen der Aufklärung im deutschsprachigen Raum. Zwei Jahre später lieferte Kant an anderer Stelle noch eine einfachere Definition der Aufklärung: „[D]ie Maxime, jederzeit selbst zu denken, ist die Aufklärung.“[9] Aber auch international erlangte der Text Bekanntheit. 1984 veröffentlichte der französische Philosoph Michel Foucault einen Essay über Kants Werk und gab ihm den gleichen Titel (Was ist Aufklärung). Foucaults Aufsatz reflektierte den gegenwärtigen Stand der Aufklärung, wobei er einen Großteil von Kants Argumentation umkehrte, aber zu dem Schluss kam, dass Aufklärung immer noch „Arbeit an unseren Grenzen erfordert“.[10] |

レセプション この記事にはまだ以下の重要な情報が欠けている: 受容と影響に関する歴史が望まれる。 調査して追加することでウィキペディアに貢献しよう。 啓蒙とは何か』は、イマヌエル・カントの最も重要な著作の一つと考えられている[8]。彼の『序論』は、ドイツ語圏で最も有名な啓蒙の命題の一つである。 その2年後、カントは別の場所で啓蒙主義のよりシンプルな定義を提示した:「つねに自分の頭で考えるという格言が啓蒙主義である」[9]。 また、このテキストは国際的にも認知されるようになった。1984年、フランスの哲学者ミシェル・フーコーはカントの著作に関するエッセイを発表し、同じ タイトル(啓蒙とは何か)をつけた。フーコーのエッセイは啓蒙主義の現状を振り返り、カントの推論の多くを覆したが、啓蒙主義は依然として「我々の限界に 取り組む必要がある」と結論づけた[10]。 |

| Ausgaben Immanuel Kant: Beantwortung der Frage: Was ist Aufklärung? In: Berlinische Monatsschrift, 1784, H. 12, S. 481–494. (Digitalisat und Volltext im Deutschen Textarchiv) Immanuel Kant: Kants gesammelte Schriften (Akademie-Ausgabe). Band VIII. de Gruyter, Berlin 1923, S. 33–42 (archive.org – Beantwortung der Frage: Was ist Aufklärung?). Immanuel Kant: Was ist Aufklärung? Ausgewählte kleine Schriften. In: Horst D. Brandt (Hrsg.): Philosophische Bibliothek (Bd.512). Hamburg 1999, ISBN 3-7873-1357-5. Literatur Ehrhard Bahr (Hrsg.): Was ist Aufklärung? Thesen und Definitionen. Kant, Erhard, Hamann, Herder, Lessing, Mendelssohn, Riem, Schiller, Wieland. ISBN 3-15-009714-2. Otfried Höffe: Immanuel Kant. 6., überarbeitete Auflage. C.H. Beck, München 2004. |

エディション イマヌエル・カント:啓蒙とは何かという問いに答える In: Berlinische Monatsschrift, 1784, H. 12, pp. イマヌエル・カント:カント著作集(アカデミー版)。de Gruyter, Berlin 1923, pp. 33-42 (archive.org - 質問に答える:啓蒙とは何か?). イマヌエル・カント:啓蒙とは何か?選集. In: Horst D. Brandt (ed.): Philosophische Bibliothek (vol.512). Hamburg 1999, ISBN 3-7873-1357-5. 文献 エールハルト・バー(編):啓蒙とは何か?テーゼと定義。カント、エアハルト、ハマーン、ヘルダー、レッシング、メンデルスゾーン、リーム、シラー、 ヴィーラント。ISBN 3-15-009714-2. オットフリート・ヘッフェ 第6版改訂版。C.H. Beck, Munich 2004. |

| Beantwortung

der Frage: Was ist Aufklärung? |

|

| https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Beantwortung_der_Frage:_Was_ist_Aufkl%C3%A4rung%3F |

| 1. Enlightenment is

man's emergence from his self-imposed immaturity.[2] Immaturity is

the inability to use one’s understanding without guidance from another.

This immaturity

is self-imposed when its cause lies not in lack of understanding, but

in lack of resolve and

courage to use it without guidance from another. Sapere Aude![3] “Have

courage to use

your own understanding!”--that is the motto of enlightenment. |

1.

啓蒙とは、人間が自ら課した未熟さから脱却することである[2]。未熟さとは、他者の指導なしに自分の理解力を活用できない状態である。この未熟さは、そ

の原因が理解力の欠如ではなく、他者の指導なしにそれを活用する決意と勇気の欠如にある場合、自ら課した未熟さである。Sapere Aude![3]

「自分の理解力を活用する勇気を持て!」―これが啓蒙のモットーである。 |

| 2. Laziness and cowardice are

the reasons why so great a proportion of men, long after

nature has released them from alien guidance (natura-liter

maiorennes),[4] nonetheless

gladly remain in lifelong immaturity, and why it is so easy for others

to establish

themselves as their guardians. It is so easy to be immature. If I have

a book to serve as

my understanding, a pastor to serve as my conscience, a physician to

determine my diet

for me, and so on, I need not exert myself at all. I need not think, if

only I can pay: others

will readily undertake the irksome work for me. The guardians who have

so benevolently

taken over the supervision of men have carefully seen to it that the

far greatest part of

them (including the entire fair sex) regard taking the step to maturity

as very dangerous,

not to mention difficult. Having first made their domestic livestock

dumb, and having

carefully made sure that these docile creatures will not take a single

step without the gocart to which they are harnessed, these guardians

then show them the danger that

threatens them, should they attempt to walk alone. Now this danger is

not actually so

great, for after falling a few times they would in the end certainly

learn to walk; but an

example of this kind makes men timid and usually frightens them out of

all further

attempts. |

2.

怠惰と臆病が、自然が人間を他者の指導から解放した後(natura-liter maiorennes)[4]

にもかかわらず、多くの人が生涯にわたる未熟な状態に甘んじ、他者が彼らの保護者として地位を確立することが容易である理由だ。未熟であることは容易だ。

もし私が理解の道具として本を持ち、良心の役割を果たす牧師を持ち、食事を決定する医師を持ち、などといったものがあれば、私は一切努力する必要はない。

考える必要はない。支払うことができれば、他人が喜んで面倒な仕事を代わりに引き受けてくれるからだ。人間の見守りを親切に引き受けた守護者たちは、彼ら

の大多数(女性全体を含む)が、成熟への一歩を非常に危険なもの、ましてや困難なものだと考えるように、慎重に手配してきた。まず、家畜を無言の動物に

し、これらの従順な生物が、つながれた荷車なしでは一歩も歩かないように慎重に確認した上で、守護者たちは、彼らが一人で歩こうとすると、どのような危険

が迫るかを示した。この危険は実際にはそれほど大きくない。なぜなら、数回転ぶうちに、彼らは最終的に歩くことを学ぶだろうから。しかし、このような例は

人間を臆病にし、通常はさらなる試みをすべて諦めさせる。 |

| 3. Thus, it is difficult for any

individual man to work himself out of the immaturity that

has all but become his nature. He has even become fond of this state

and for the time

being is actually incapable of using his own understanding, for no one

has ever allowed

him to attempt it. Rules and formulas, those mechanical aids to the

rational use, or rather

misuse, of his natural gifts, are the shackles of a permanent

immaturity. Whoever threw

them off would still make only an uncertain leap over the smallest

ditch, since he is

unaccustomed to this kind of free movement. Consequently, only a few

have succeeded,

by cultivating their own minds, in freeing themselves from immaturity

and pursuing a

secure course. |

3.

したがって、いかなる個人も、ほとんど自分の本性となった未熟さから自ら脱却することは困難である。彼はこの状態を好むようになり、当面は自分の理解力を

実際に活用することができない。なぜなら、これまで誰も彼にそれを試みることを許さなかったからだ。規則や定式、つまり、彼の天賦の才能を合理的に活用、

あるいはむしろ誤用するための機械的な補助手段は、永続的な未熟さの束縛である。それらを投げ捨てた者は、この種の自由な動きに慣れていないため、ごくわ

ずかな溝を飛び越えるだけの不安定な跳躍しかできないだろう。その結果、自分の心を養うことで、未熟さから脱却し、確実な道を進むことに成功したのはごく

わずかの人たちだけである。 |

| 4. But that the public should

enlighten itself is more likely; indeed, if it is only allowed

freedom, enlightenment is almost inevitable. For even among the

entrenched guardians

of the great masses a few will always think for themselves, a few who,

after having

themselves thrown off the yoke of immaturity, will spread the spirit of

a rational

appreciation for both their own worth and for each person's calling to

think for himself.

But it should be particularly noted that if a public that was first

placed in this yoke by the guardians is suitably aroused by some of

those who are altogether incapable of

enlightenment, it may force the guardians themselves to remain under

the yoke--so

pernicious is it to instill prejudices, for they finally take revenge

upon their originators, or

on their descendants. Thus a public can only attain enlightenment

slowly. Perhaps a

revolution can overthrow autocratic despotism and profiteering or

power-grabbing

oppression, but it can never truly reform a manner of thinking;[5]

instead, new prejudices,

just like the old ones they replace, will serve as a leash for the

great unthinking mass. |

4.

しかし、大衆が自ら啓蒙される可能性はもっと高い。実際、自由が許されれば、啓蒙はほぼ必然的に起こるだろう。なぜなら、大衆の堅固な守護者たちの中に

も、常に自ら考える者が少数ながら存在し、その者たちは、自ら未熟さのくびきから脱した後、自らの価値と、各人が自ら考えるべきという使命を合理的に評価

する精神を広めるからだ。しかし、特に注意すべきは、守護者たちによって最初にこの束縛に置かれた大衆が、啓蒙にまったく無能な者たちによって適切に刺激

された場合、守護者たち自身をその束縛の下に留まらせることになるかもしれないということだ。偏見を植え付けることは、その偏見が最終的にその生みの親、

あるいはその子孫たちに復讐する、というように、非常に有害なものだからだ。したがって、公衆は啓蒙をゆっくりとしか達成できない。革命は専制的な独裁や

利益追求、権力奪取の抑圧を打倒することはできるかもしれないが、思考の方法を真に改革することはできない;[5]

代わりに、古い偏見と同じように、新しい偏見が、思考しない大衆の鎖として機能するだろう。 |

| 5. Nothing is required for this

enlightenment, however, except freedom; and the freedom

in question is the least harmful of all, namely, the freedom to use

reason publicly in all

matters. But on all sides I hear: “Do not argue!” The officer says, “Do

not argue, drill!”

The tax man says, “Do not argue, pay!” The pastor says, “Do not argue,

believe!” (Only

one ruler in the world[6] says, “Argue as much as you want and about

what you want, but

obey!”) In this we have [examples of] pervasive restrictions on

freedom. But which

restriction hinders enlightenment and which does not, but instead

actually advances it? I

reply: The public use of one’s reason must always be free, and it alone

can bring about

enlightenment among mankind; the private use of reason may, however,

often be very

narrowly restricted, without otherwise hindering the progress of

enlightenment. By the

public use of one's own reason I understand the use that anyone as a

scholar makes of

reason before the entire literate world. I call the private use of

reason that which a person

may make in a civic post or office that has been entrusted to him.[7]

Now in many affairs

conducted in the interests of a community, a certain mechanism is

required by means of

which some of its members must conduct themselves in an entirely

passive manner so

that through an artificial unanimity the government may guide them

toward public ends,

or at least prevent them from destroying such ends. Here one certainly

must not argue,

instead one must obey. However, insofar as this part of the machine

also regards himself

as a member of the community as a whole, or even of the world

community, and as a

consequence addresses the public in the role of a scholar, in the

proper sense of that term,

he can most certainly argue, without thereby harming the affairs for

which as a passive

member he is partly responsible. Thus it would be disastrous if an

officer on duty who

was given a command by his superior were to question the

appropriateness or utility of

the order. He must obey. But as a scholar he cannot be justly

constrained from making

comments about errors in military service, or from placing them before

the public for its

judgment. The citizen cannot refuse to pay the taxes imposed on him;

indeed,

impertinent criticism of such levies, when they should be paid by him,

can be punished as

a scandal (since it can lead to widespread insubordination). But the

same person does not

act contrary to civic duty when, as a scholar, he publicly expresses

his thoughts regarding

the impropriety or even injustice of such taxes. Likewise a pastor is

bound to instruct his

catecumens and congregation in accordance with the symbol of the church

he serves, for

he was appointed on that condition. But as a scholar he has complete

freedom, indeed

even the calling, to impart to the public all of his carefully

considered and wellintentioned thoughts concerning mistaken aspects of

that symbol,[8] as well as his

suggestions for the better arrangement of religious and church matters.

Nothing in this

can weigh on his conscience. What he teaches in consequence of his

office as a servant of

the church he sets out as something with regard to which he has no

discretion to teach in

accord with his own lights; rather, he offers it under the direction

and in the name of another. He will say, “Our church teaches this or

that and these are the demonstrations it

uses.” He thereby extracts for his congregation all practical uses from

precepts to which

he would not himself subscribe with complete conviction, but whose

presentation he can

nonetheless undertake, since it is not entirely impossible that truth

lies hidden in them,

and, in any case, nothing contrary to the very nature of religion is to

be found in them. If

he believed he could find anything of the latter sort in them, he could

not in good

conscience serve in his position; he would have to resign. Thus an

appointed teacher’s

use of his reason for the sake of his congregation is merely private,

because, however

large the congregation is, this use is always only domestic; in this

regard, as a priest, he is

not free and cannot be such because he is acting under instructions

from someone else.

By contrast, the cleric--as a scholar who speaks through his writings

to the public as such,

i.e., the world--enjoys in this public use of reason an unrestricted

freedom to use his own

rational capacities and to speak his own mind. For that the (spiritual)

guardians of a

people should themselves be immature is an absurdity that would insure

the perpetuation

of absurdities. |

5.

この啓蒙には、自由以外の何物も必要とされない。ここでいう自由とは、あらゆる事柄について公に理性を用いる自由という、最も害のない自由のことだ。しか

し、あらゆる方面から「議論するな!」という声が聞こえる。軍人は「議論するな、訓練しろ!」と、税吏は「議論するな、税金を払え!」と叫ぶ。牧師は「議

論するな、信じろ!」と言う。(世界にはただ一人の支配者[6]だけが「好きなだけ、好きなことについて議論せよ、しかし従え!」と言う。)ここに、自由

に対する広範な制限の例がある。しかし、どの制限が啓蒙を妨げるのか、どの制限が逆に啓蒙を促進するのか?私は答える:

個人の理性の公的な使用は常に自由でなければならない。それだけが人類の啓蒙をもたらすことができる。しかし、個人の理性の私的な使用は、啓蒙の進歩を妨

げることなく、しばしば非常に厳格に制限されることがある。個人の理性の公的な使用とは、学者として、文字を解く世界全体の前で理性を用いることを指す。

私は、ある人が、自分に委ねられた市民的職位や公職において行う理性の使用を、私的理性と呼んでいる[7]。さて、共同体の利益のために行われる多くの事

柄では、その一部の構成員が完全に受動的な態度で行動し、人為的な意見の一致によって、政府が彼らを公共の目的へと導く、あるいは少なくともその目的を破

壊することを防ぐための、ある種の仕組みが必要とされる。ここでは議論するのではなく、従わなければならない。しかし、この機械の一部が、自身をコミュニ

ティ全体、あるいは世界コミュニティの成員として見なし、その結果、学者の役割で公衆に語りかける場合、彼は議論することができる。そして、受動的な成員

として部分的に責任を負う事務に害を及ぼすことなく、そうすることができる。したがって、上司から命令を受けた当直の将校が、その命令の適切性や有用性を

疑問視することは、災厄を招く。彼は従わなければならない。しかし、学者として、彼は軍事サービスの誤りについてコメントすることを正当に制約されること

はなく、それらを公衆の判断に委ねることもできる。市民は、自分に課せられた税金の支払いを拒否することはできない。実際、自分が支払うべき税金を不遜に

批判することは、スキャンダルとして罰せられる可能性がある(それは、広範な不服従につながる可能性があるため)。しかし、同じ人物が、学者として、その

ような税金の不適切さや、さらにはその不正について、自分の考えを公に表明することは、市民としての義務に反する行為ではない。同様に、牧師は、自身が仕

える教会の象徴に従って、洗礼志願者や信徒を指導する義務がある。なぜなら、彼はその条件で任命されたからである。しかし、学者として、彼は、その象徴の

誤った側面に関する慎重に検討され、善意に満ちたすべての考えを、また宗教や教会に関するより良い制度の提案を、公衆に伝える完全な自由、甚至いは召命を

有する。これには、彼の良心に何の重荷も課されない。彼が教会の奉仕者としての職務に基づいて教えることは、自身の判断で教える自由がないものとして提示

する。むしろ、彼は他者の指導と名の下にそれを提示する。彼は「私たちの教会はこれこれと教え、その根拠はこれこれです」と述べる。これにより、彼は自身

の教団に対して、自身は完全な確信を持って賛同しない教義から、実践的な用例を抽出する。しかし、これらの教義には真実が隠されている可能性が完全に否定

できないため、また、いずれにせよ、宗教の本質に反するものは含まれていないため、その提示を引き受けることができる。もし彼が後者のようなものを発見し

た場合、良心に従ってその職に就くことはできず、辞任しなければならない。したがって、任命された教師が教会の信徒のために理性を用いることは、単に私的

なものに過ぎない。なぜなら、教会の信徒がどれだけ多くても、この理性の使用は常に家庭内のものであり、この点において、彼は神父として自由ではなく、他

者からの指示に従って行動しているため、自由であることはできないからだ。対照的に、聖職者は、学者として、その著作を通じて、公衆、すなわち世界に対し

て発言する者として、この公共的な理性の使用において、自らの理性を用いて自分の考えを自由に発言する無制限の自由を享受している。人民の(精神的)守護

者が、自ら未熟であるということは、不条理の永続を保証する不条理である。 |

| 6. But would a society of

pastors, perhaps a church assembly or venerable presbytery (as

those among the Dutch call themselves), not be justified in binding

itself by oath to a

certain unalterable symbol in order to secure a constant guardianship

over each of its

members and through them over the people, and this for all time: I say

that this is wholly

impossible. Such a contract, whose intention is to preclude forever all

further

enlightenment of the human race, is absolutely null and void, even if

it should be ratified

by the supreme power, by parliaments, and by the most solemn peace

treaties. One age

cannot bind itself, and thus conspire, to place a succeeding one in a

condition whereby it

would be impossible for the later age to expand its knowledge

(particularly where it is so

very important), to rid itself of errors, and generally to increase its

enlightenment. That

would be a crime against human nature, whose essential destiny lies

precisely in such

progress; subsequent generations are thus completely justified in

dismissing such

agreements as unauthorized and criminal. The criterion of everything

that can be agreed

upon as a law by a people lies in this question: Can a people impose

such a law on

itself?[9] Now it might be possible, in anticipation of a better state

of affairs, to introduce

a provisional order for a specific, short time, all the while giving

all citizens, especially

clergy, in their role as scholars, the freedom to comment publicly,

i.e., in writing, on the

present institution's shortcomings. The provisional order might last

until insight into the

nature of these matters had become so widespread and obvious that the

combined (if not

unanimous) voices of the populace could propose to the crown that it

take under its

protection those congregations that, in accord with their newly gained

insight, had

organized themselves under altered religious institutions, but without

interfering with

those wishing to allow matters to remain as before. However, it is

absolutely forbidden

that they unite into a religious organization that nobody may for the

duration of a man's

lifetime publicly question, for so doing would deny, render fruitless,

and make

detrimental to succeeding generations an era in man's progress toward

improvement. A

man may put off enlightenment with regard to what he ought to know,

though only for a

short time and for his own person; but to renounce it for himself, or,

even more, for

subsequent generations, is to violate and trample man's divine rights

underfoot. And what

a people may not decree for itself may still less be imposed on it by a

monarch, for his lawgiving authority rests on his unification of the

people's collective will in his own. If he

only sees to it that all genuine or purported improvement is consonant

with civil order, he

can allow his subjects to do what they find necessary to their

spiritual well-being, which

is not his affair. However, he must prevent anyone from forcibly

interfering with

another's working as best he can to determine and promote his

well-being. It detracts

from his own majesty when he interferes in these matters, since the

writings in which his

subjects attempt to clarify their insights lend value to his conception

of governance. This

holds whether he acts from his own highest insight--whereby he calls

upon himself the

reproach, “Caesar non eat supra grammaticos”[10]—as well as, indeed

even more,

when he despoils his highest authority by supporting the spiritual

despotism of some

tyrants in his state over his other subjects. |

6.

しかし、牧師たちによる社会、おそらく教会議会や由緒ある長老会(オランダの人々が自らをそう呼んでいる)が、その構成員一人一人、そして彼らを通じて人

民を永続的に保護するために、ある不変の象徴に誓約によって自らを拘束することは正当ではないだろうか。私は、それはまったく不可能だと言う。人類のさら

なる啓蒙を永遠に排除することを目的としたこのような契約は、たとえ最高権力、議会、そして最も厳粛な平和条約によって批准されたとしても、まったく無効

である。ある時代が、後世の時代を、その知識の拡大(特にそれが非常に重要な場合)、誤りの排除、そして全般的な啓蒙の向上を不可能にするような状況に陥

らせるような契約を結び、共謀することはできない。それは、まさにそのような進歩に本質的な運命にある人間性に対する犯罪であり、後世の世代は、そのよう

な契約を無効かつ犯罪的なものと見なすことは完全に正当である。人民が法律として合意できるすべてのものの基準は、この質問にある。人民は、そのような法

律を自らに課すことができるか?[9]

より良い状況になることを期待して、特定の短期間、暫定的な秩序を導入することは可能かもしれない。その間、すべての市民、特に学者としての役割を担う聖

職者は、現在の制度の問題点について、公に、すなわち文書で自由に意見を述べることができるようにすべきだ。この暫定的な秩序は、これらの問題の本質に関

する理解が広く明白になり、民衆の連合した(もしも一致したものでないとしても)声が、王冠に対し、新たな理解に基づいて改変された宗教機関の下で組織化

された教団を保護下に置くよう提案できるまで継続されるかもしれない。ただし、現状を維持したいと望む者には干渉しないこと。ただし、誰もその生涯にわ

たって公に疑問を呈することができない宗教組織に結集することは、絶対に禁止される。なぜなら、そうすることは、人類の進歩と改善の時代を否定し、無意味

にし、後世に害を及ぼすことになるからである。人は、自分が知るべきことについて、たとえ短期間で、かつ自分自身についてのみであっても、その啓蒙を延期

することはできる。しかし、自分自身のために、あるいはさらに、後世のためにそれを放棄することは、人間の神聖な権利を侵害し、踏みにじるものである。そ

して、人民が自ら決定できないことは、君主によって人民に課せられることはさらにあり得ない。なぜなら、君主の立法権は、人民の集合的意志を自らの意志に

統一することにあるからだ。君主は、すべての真または真とみなされる改善が、市民秩序と調和していることを確認するだけであり、人民の精神的幸福のために

必要とみなされることは、君主の関知するところではない。しかし、彼は、他者が自らの福祉を決定し促進するために最善を尽くすことを、強制的に妨害する者

を阻止しなければならない。彼がこれらの問題に干渉することは、彼の威厳を損なう。なぜなら、臣民が自らの洞察を明確にしようとする著作は、彼の統治の理

念に価値を与えるからである。これは、彼が自身の最高の見識に基づいて行動する場合——すなわち「カエサルは文法学者よりも上ではない」[10]という非

難を自身に課す場合——だけでなく、むしろ、国家内の他の臣民に対して一部の独裁者の精神的専制を支持することで、自身の最高権威を剥奪する場合にも当て

はまる。 |

| 7. If it is now asked, “Do we

presently live in an enlightened age?” the answer is, “No,

but we do live in an age of enlightenment.” As matters now stand, a

great deal is still

lacking in order for men as a whole to be, or even to put themselves

into a position to be

able without external guidance to apply understanding confidently to

religious

issues. But we do have clear indications that the way is now being

opened for men to

proceed freely in this direction and that the obstacles to general

enlightenment--to their

release from their self-imposed immaturity—are gradually diminishing.

In this regard,

this age is the age of enlightenment, the century of Frederick.[11] |

7.

もし今、「私たちは現在、啓蒙の時代を生きているのか」と問われたら、答えは「いいえ、しかし私たちは啓蒙の時代を生きている」となる。現在の状況では、

人間全体が、あるいは少なくとも人間が自らを、外部の指導なしに宗教的問題に理解を自信を持って適用できる立場に置くためには、まだ多くのものが欠如して

いる。しかし、人間がこの方向へ自由に進む道が開かれつつあり、一般の啓蒙の障害——自己課した未熟さからの解放の障害——が徐々に減少しつつある明確な

兆候がある。この点において、この時代は啓蒙の時代であり、フリードリヒの世紀である。[11] |

| 8. A prince who does not find it

beneath him to say that he takes it to be his duty to

prescribe nothing, but rather to allow men complete freedom in

religious matters—who

thereby renounces the arrogant title of tolerance—is himself

enlightened and deserves to

be praised by a grateful present and by posterity as the first, at

least where the

government is concerned, to release the human race from immaturity and

to leave

everyone free to use his own reason in all matters of conscience. Under

his rule,

venerable pastors, in their role as scholars and without prejudice to

their official duties,

may freely and openly set out for the world's scrutiny their judgments

and views, even

where these occasionally differ from the accepted symbol. Still greater

freedom is

afforded to those who are not restricted by an official post. This

spirit of freedom is

expanding even where it must struggle against the external obstacles of

governments that

misunderstand their own function. Such governments are illuminated by

the example

that the existence of freedom need not give cause for the least concern

regarding public

order and harmony in the commonwealth. If only they refrain from

inventing artifices to

keep themselves in it, men will gradually raise themselves from

barbarism. |

8.

何も規定することは自分の義務ではない、むしろ宗教問題に関しては人々に完全な自由を与えることが自分の義務であると公言することを卑しいこととは考えな

い君主は、それによって傲慢な「寛容」という称号を放棄するものであり、それ自体、啓蒙された人物であり、少なくとも政治の分野においては、人類を未熟か

ら解放し、良心の問題に関してはすべての人に自分の理性を自由に用いることを認めた最初の人物として、現在の世代および後世の世代から称賛に値する。彼の

支配下では、尊敬すべき牧師たちは、学者としての役割において、その公務に支障をきたすことなく、たとえそれが時折、一般に認められた象徴と異なる場合で

も、自分の判断や見解を自由に、そして公然と世間に発表することができる。公職に縛られない者たちは、さらに大きな自由を享受している。この自由の精神

は、自らの機能を誤解する政府の外部的な障害と闘わなければならない場所でも広がっている。そのような政府は、自由の存在が公共の秩序と調和に関する最も

小さな懸念の理由となる必要はないという例によって照らされている。彼らが自らをその中に留めるための策略を考案することを控えるなら、人々は徐々に野蛮

から脱却していくだろう。 |

| 9. I have focused on religious

matters in setting out my main point concerning

enlightenment, i.e., man's emergence from self-imposed immaturity,

first because our

rulers have no interest in assuming the role of their subjects'

guardians with respect to the

arts and sciences, and secondly because that form of immaturity is both

the most

pernicious and disgraceful of all. But the manner of thinking of a head

of state who

favors religious enlightenment goes even further, for he realizes that

there is no danger to

his legislation in allowing his subjects to use reason publicly and to

set before the world

their thoughts concerning better formulations of his laws, even if this

involves frank

criticism of legislation currently in effect. We have before us a

shining example, with respect to which no monarch surpasses the one

whom we honor. |

9.

私は、啓蒙に関する私の主要な主張、すなわち、人間が自ら課した未熟さから脱却することについて述べる際に、宗教的問題を中心に論じてきた。その理由は、

第一に、私たちの支配者は、芸術や科学に関して臣民の保護者としての役割を担うことに何の関心も持っていないからであり、第二に、その未熟さは、あらゆる

未熟さの中で最も有害で恥ずべきものであるからである。しかし、宗教的啓蒙を支持する国家元首の思考方法はさらに進んでいる。なぜなら、彼は、臣民が公の

場で理性を用い、現在の法律のより良い制定に関する考えを世界に提示することを許しても、その立法に危険はないと気づいているからだ。この点において、私

たちが敬愛する君主を超える君主はいない。 |

| 10. But only a ruler who is

himself enlightened and has no dread of shadows, yet who

likewise has a well-disciplined, numerous army to guarantee public

peace, can say what

no republic[12] may dare, namely: “Argue as much as you want and about

what you want,

but obey!” Here as elsewhere, when things are considered in broad

perspective, a strange,

unexpected pattern in human affairs reveals itself, one in which almost

everything is

paradoxical. A greater degree of civil freedom seems advantageous to a

people's

spiritual freedom; yet the former established impassable boundaries for

the latter;

conversely, a lesser degree of civil freedom provides enough room for

all fully to expand

their abilities. Thus, once nature has removed the hard shell from this

kernel for which

she has most fondly cared, namely, the inclination to and vocation for

free thinking, the

kernel gradually reacts on a people’s mentality (whereby they become

increasingly able

to act freely), and it finally even influences the principles of

government, which finds that

it can profit by treating men, who are now more than machines, in

accord with their

dignity.* |

10.

しかし、自ら悟りを開き、影を恐れない統治者でありながら、同時に公共の平和を保証する規律正しく数多くの軍隊を擁する者だけが、いかなる共和国[12]

も敢えて言えないことを言うことができる。すなわち、「好きなだけ、好きなことを議論せよ。しかし、従え!」と。ここでも他の場合と同様、物事を広い視野

で考えると、人間の事柄には不思議な、予期せぬパターンが浮かび上がる。そのパターンでは、ほとんどすべてが矛盾している。市民の自由度が高いほど、人民

の精神的自由も拡大すると思われるが、しかし、前者は後者に越えられない境界線を設定し、逆に、市民の自由度が低いほど、すべての人が自分の能力を十分に

発揮できる余地が生まれる。したがって、自然が、最も大切にしてきたこの核、すなわち自由な思考への傾向や天職から、その硬い殻を取り去ると、その核は徐

々に人民の精神に影響を与え(それによって人民はますます自由に行動できるようになる)、最終的には、もはや機械以上の存在となった人間をその尊厳に応じ

て扱うことで利益を得られることを認識した政府の基本原則にも影響を及ぼすようになる。 |

| Immanuel Kant, Konigsberg in

Prussia,

30 September 1784

*Today I read in Büsching’s Wöchentliche Nachtrichten for September 13th a notice concerning this month’s Berlinischen Monatsschift that mentions Mendelssohn’s answer to this same question. I have not yet seen this journal, otherwise I would have withheld the foregoing reflections, which I now set out in order to see to what extent two persons thoughts may coincidentally agree. |

イマヌエル・カント、プロイセン王国ケーニヒスベルク、1784年9月

30日 *本日、ビュッシングの『Wöchentliche Nachtrichten』9月13日号で、今月の『Berlinischen Monatsschift』に関する記事を読み、この同じ質問に対するメンデルスゾーンの回答について知った。私はまだこの雑誌を読んでいないので、もし 読んでいたら、上記の考察は控えただろう。しかし、2人の人格の考えが偶然一致している程度を確認するため、ここでその考察を述べようと思う。 |

| [1] A. A., VIII, 33-42. This essay first appeared in the Berlinische Monatsschrift,

December, 1784.

[2] The German is Unmündigkeit, which quite literally means “minority,” where one is

referring to the inability to make decisions for oneself. Kant’s point in the essay is that

by virtue of understanding and reason men have the inherent right and ability to make all

intellectual, political and religious decisions for themselves. That they do not is a

function of certain, perhaps implicit, choices they make in regard to exercising rights and

developing capacities.

[3] “Dare to Know!” (Horace, Epodes, 1, 2, 40.). This motto was adopted by the Society

of the Friends of Truth, an important circle of the German Enlightenment.

[4] “Those who have come of age by virtue of nature.”

[5] The term Kant uses here and later, on p. 41, is Denkungsart; it occurs in the second

edition preface to the Critique of Pure Reason, where he works out his famous analogy of

the Copernican Revolution in philosophy, which he refers to as a revolution in the

method of thought (B vii-xxiv). The term refers to one’s characteristic pattern of thought,

whether it is marked by systematic, rational procedures or by prejudice and superstition,

criticism or dogmatism.

[6] Frederick II (the Great) of Prussia.

[7] See On the Proverb: That May be True in Theory, But Is of No Practical Use:

“According to [Hobbes] (de Cive, Chapter 7, section 14) the nation’s ruler is not

contractually obligated to the people and cannot wrong the citizens (no matter how he

might dispose of them.)—This proposition would be entirely correct, if by “wrong”

[Unrecht] one understood an injury [Läsion] (Kant’s point here seems to be that if by

“wrong” Hobbes means physical injury, his view can be accepted; but if it includes

violation of rights, it must certainly be incorrect.) that gave the injured party a coercive

right against the one who had wronged him; but stated so generally, the proposition is

terrifying.

The cooperative subject must be able to assume that his ruler does not want to

wrong him. Consequently on this assumption—because every man has inalienable rights

that he cannot give up even if he wanted to and in regard to which he has the authority to

be his own judge—the wrong that in his view befalls him occurs only as a function of

error, or from ignorance of certain of the consequences of the supreme power’s

laws. Thus, regarding whatever in the ruler’s decrees seem to wrong the commonwealth,

the citizen must retain the authority to his opinions publicly known, and this authority

must receive the ruler’s approval. For to assume that the ruler cannot ever err or that he

cannot be ignorant of something would be to portray him as blessed with divine

inspiration and as elevated above the rest of humanity. Hence freedom of the pen—

within the bounds of respect and love for the constitution one lives under, respect and

love that are maintained by the subjects’ liberal manner of thought [Denkungsart], a way

of thinking instilled in them by that very constitution (and to which way of thinking the

7

pens restrict one another so as not to lose their freedom)—is the sole protector of the

people’s rights. To want to deprive citizens of this right is not only tantamount to

depriving them of all claim to rights in relation to the supreme commander (according to

Hobbes), but it also denies him, whose will commands subjects as citizens only because it

represents the general will of the people, all knowledge of such matters as he would

himself change if he knew about them; and denying such freedom places the commander

in a self-contradictory position. Encouraging the leader to suspect that unrest might be

aroused by men thinking out loud and for themselves is to awaken in him both distrust in

his own power and hate for his people.

The general principle by which a people may judge, though merely negatively, as

to whether the supreme legislature has not decreed with the best of intentions is contained

in this proposition: Whatever a people cannot decree for itself cannot be decreed for it by

the legislator.

[8] Kant distinguishes between two classes of concepts, those that we can schematize, i.e.,

directly represent in experience (intuition), and those that we must symbolize, i.e.,

indirectly represent in experience (intuition). Symbolized concepts, such as the one we

have of God, are those for which no experience can provide adequate content;

consequently, experience can only be used to indicate the content we intend. All

religious concepts have this character. By symbol in this context, then, Kant means those

beliefs and practices in which a group expresses the content of this concept of the divine

(Critique of Judgment, 351-54).

[9] This would seem a peculiarly political expression of the Categorical Imperative,

particularly as it is expressed in Groundings, 428-29.

[10] “Caesar is not above the grammarians.” See Perpetual Peace, 368 f.

[11] Frederick II (the Great), King of Prussia.

[12] The term Kant uses here is Freistaat, which is idiomatically translated

“republic.” However, Kant never again uses the Germanic rooted word in the essays

included in this volume (Hackett’s Perpetual Peace and Other Essays). In all the other

essays he uses the Latin loan word Republic. I point this out because what Kant says here

about a Freistaat is inconsistent with what he says elsewhere about a Republic. |

[1]

A. A., VIII, 33-42. このエッセイは、1784年12月の『ベルリン月報』に初めて掲載された。[2]

ドイツ語の「Unmündigkeit」は、文字通り「未成年」を意味し、自己決定ができない状態を指す。カントのこの論文における主張は、理解と理性に

よって、人間は知的、政治的、宗教的なすべての決定を自己で行う固有の権利と能力を有しているということだ。彼らがそうしないのは、権利の行使や能力の発

達に関する、おそらくは暗黙の選択の結果である。[3]

「知ろうとする勇気を持て!」(ホラティウス、エポデス、1、2、40)。このモットーは、ドイツ啓蒙思想の重要なサークルである「真実の友協会」によっ

て採用された。[4] 「自然によって成人した者たち」。[5]

カントがここや後述の41ページで使用する用語は「Denkungsart」で、これは『純粋理性批判』の第2版序文において、彼が哲学におけるコペルニ

クス的転回という有名な類推を展開する際に用いられたもので、彼はこれを「思考の方法の革命」と呼んでいる(B

vii-xxiv)。この用語は、体系的で合理的な手続きによって特徴付けられるか、偏見や迷信、批判や独断によって特徴付けられるかに関わらず、個人の

思考の特有のパターンを指す。[6] プロイセンのフリードリヒ2世(大帝)。[7]

「理論的にはそうかもしれない、しかし実際には役に立たない」という諺についてを参照のこと。「(ホッブズによると(『市民について』第 7 章、第

14

節)、国の支配者は国民に対して契約上の義務を負っておらず、国民に対して不正を行うことはできない(国民をどのように処分しても)。[Unrecht]

が、被害者に加害者に対して強制的な権利を与える傷害 [Läsion]

を意味する場合だ。しかし、このように一般的に述べると、この主張は恐ろしいものになる。協力的な主体は、自分の支配者が自分に不正を行わないと想定でき

なければならない。したがって、この想定に基づいて、すべての者は、たとえ望んだとしても放棄できない、そして自分自身で判断できる不可侵の権利を有する

ことから、その者が不正だと考えることは、誤りの結果、あるいは最高権力の法律の特定の帰結に関する無知から生じるものだけである。したがって、支配者の

法令のうち、共同体に不当と思われるものについては、市民は自分の意見を公に表明する権限を保持しなければならず、この権限は支配者の承認を受けなければ

ならない。なぜなら、支配者が決して誤りを犯さない、あるいは何も知らないとは仮定することは、支配者を神聖な霊感に恵まれた、他の人間よりも高貴な存在

として描くことになるからだ。したがって、自由な言論の自由は、自分が暮らす憲法を尊重し、愛するという範囲内で、その憲法によって国民に植えつけられた

自由な考え方(Denkungsart)によって維持される、憲法を尊重し、愛するという範囲内で、自由な言論の自由は、人民の権利の唯一の保護者であ

る。市民からこの権利を奪おうとするのは、(ホッブズによれば)最高司令官に対するすべての権利を剥奪することと同じであるだけでなく、人民の総意志を表

すからこそ市民として臣民を支配するその意志を、その意志が知れば自ら変更するであろう事柄に関するすべての知識から否定することになり、そのような自由

を否定することは、最高司令官を自己矛盾の立場に置くことになる。指導者に、人々が自分の考えを率直に口にするによって不安が生じるかもしれないという疑

念を抱かせることは、指導者に自分の権力に対する不信と人民に対する憎悪を呼び覚ますことになる。最高立法機関が最善の意図をもって法令を制定したかどう

かを、人民が、たとえ否定的にでも判断できる一般的な原則は、次の命題に含まれている。人民が自ら決定できないことは、立法者によって決定することはでき

ない。[8]

カントは、概念を二つのクラスに区別する。一つは、経験(直観)で直接的に表すことができるもの(直観)であり、もう一つは、経験(直観)で間接的に表す

必要があるもの(象徴)である。神に関する概念のような象徴化された概念は、経験が適切な内容を供給できないものだから、経験は、私たちが意図する内容を

示すためにしか使用できない。すべての宗教的概念はこの性格を有する。この文脈における「象徴」とは、カントが、集団が神的概念の内容を表現する信念や実

践を指す(『判断力批判』、351-54)。[9] これは、特に『基礎』428-29

ページで表現されているように、定言命法の特異な政治的表現のように思われる。[10] 「カエサルは文法学者よりも上ではない」

『永遠の平和』368 ページ以降を参照。[11] プロイセン王フリードリヒ 2 世(大王)。[12]

カントがここで使用している用語は「Freistaat」で、慣用的に「共和国」と翻訳されている。しかし、カントは本書に収録されたエッセイ(ハケット

の『永久平和とその他のエッセイ』)において、このゲルマン語由来の単語を二度と使用していない。他のすべてのエッセイでは、ラテン語由来の

「Republic」という借用語を使用している。この点を指摘するのは、カントがここで「Freistaat」について述べていることが、他の場所で

「Republic」について述べていることと矛盾しているからである。 |

| https://www.nypl.org/sites/default/files/kant_whatisenlightenment.pdf |

☆カントの4つの審問(→このセクション は今後は「カントの三つ審問」にて展開します)

1) 「私は何を知りうるか[‚Was kann ich wissen?‘]——理性は知識の能力(「私は何を知りうるか[‚Was kann ich wissen?‘]」)に向けられている。これが『純粋理性批判』の主題である。

2) 「私は何をすべきか[‚Was soll ich tun?‘]」——人間の行動(「私は何をすべきか[‚Was soll ich tun?‘]」)は、まったく別の方向における理性的考察の内容である。これが『実践理性批判(KpV)』の 主題である。カントにとって、「存在すること」と「なすべきこと」は、一つの理性の非独立的な二つの側面である。人間の実践にとって、自由は自律的決定の 基礎として必要であり明白であるが、理論的理性においては、それは可能であることを示すことができるだけである。自由のない行動は考えられない。私たちは 道徳法則を意識することによってのみ、自由を認識する。

3) 「私は何を望むか[‚Was darf ich hoffen?‘]」——「純粋実践理性の弁証法」では、「何を望むか[‚Was darf ich hoffen?‘]」という問いが考察の対象となる。ここでカントは最高善の決定についての考えを展開する。実践的な意味での無 条 件の問題である。『実践理性批判(KpV)』においてカントは、自由、神、魂の不滅という無条件の観念は証明することはできないが、調整的観念としては可 能であると考えられ ることを示した。カントの見解では、これらの観念は実践理性にとって必要であり、それゆえ純粋実践理性の真の定立とみなすことができる。『実践理性批判 (KpV)』の非常に短 い第二部である『方法序説』において、カントは道徳教育の簡単な概念を概説している。実践的な道徳哲学に関するカントの見解は、『道徳の形而上学』や『道 徳哲学講義』に見出すことができる。

4)

人間とはなにか?——『判断力批判?』あるいは『人間学』

++

リ ンク

リ ンク(主体)

リ ンク(啓蒙)

文献

その他の情報

+++

Copyleft,

CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099