人類史における依存症の意味

The significance of addiction in human history

池田光穂

☆人類史とはなにか?

人類史あ

るいは世界史とは、先史時代から現代に至る人類の記録である。現代人は約30万年前にアフリカで進化し、当初は狩猟採集民として生活した。最終氷

期にアフリカから移住し、1万2000年前の氷期終結までに南極を除く大陸全域に広がった。その後間もなく、西アジアにおける新石器時代の革命が植物と動

物の最初の体系的な飼育をもたらし、多くの人類が遊牧生活から定住農民としての生活へと移行した。人間社会の複雑化に伴い、会計と文字の体系が必要となっ

た。

こうした発展がメソポタミア、エジプト、インダス文明、中国における初期文明の出現を可能にし、紀元前3500年に古代時代の幕開けを告げた。これらの文

明は地域帝国形成を支え、変革的な哲学・宗教思想の誕生を育む肥沃な土壌となった。青銅器時代後期にはヒンドゥー教が、そして軸心時代には仏教、儒教、ギ

リシャ哲学、ジャイナ教、ユダヤ教、道教、ゾロアスター教が相次いで現れた。…… 18世紀まで

に、知識と技術の蓄積は臨界点に達し、産業革命を引き起こした。これは「大分岐」の重要な要素であり、西暦1800年頃から始まる近代期の幕開けとなっ

た。生産力の急速な成長は国際貿易と植民地化をさらに促進し、グローバル化のプロセスにおいて異なる文明を結びつけ、19世紀を通じてヨーロッパの支配を

確固たるものにした。過去250年間、二度の壊滅的な世界大戦を含むこの期間において、人口、農業、産業、商業、科学的知識、技術、通信、軍事力、環境破

壊など、多くの分野で大きな加速が見られた。

人類史の研究は、歴史学、考古学、人類学、言語学、遺伝学などの学術分野からの知見に依存している。分かりやすい概観を提供するため、研究者は様々な時代

区分によって人類史を分類している。

☆アディクションとはなにか?

依存症(アディクション)は、

実質的な害やその他の否定的な結果にもかかわらず、薬物を使

用したり、自然な報酬をもたらす行動に関与したりしたいという持続的で強い衝動を特徴とする神経心理学的障害である。薬物の反復使用は、食物や恋愛のよう

な自然な報酬と同様に、シ

ナプスにおける脳機能を変化させ、渇望を持続させ、既存の脆弱性を持つ人々の自制心を弱める。この現象——薬物が脳機能を再形成する——は、依存症の発症

に関与する神経生物学的要因だけでなく、複雑で多様な心理社会的要因を伴う脳疾患としての依存症の理解につながっている(→「依存症の分子メカニズム」)。

★アディクション批判の論点:依存症と文明(広域共通文化)

I. 近代文明と依存症の構造的関係

II. テクノロジー文明と新たな依存形態

III. 資本主義システムとの共犯関係

IV. 代替理論的アプローチ

★検証すべき仮説

仮説1: アディクションの「病 理化」は欧米的生物医療モデ ルの輸入である

仮説2: 心理的・社会的要因は グローバル不均衡と密接に関 係している

仮説3: 文化的意味は「アディクション」概念とずれている

仮説4: 学術研究者の言説も脱 植民地的視点を欠いている

仮説5: 「アディクション」は ポストコロニアル的支配の言 説的装置である

★仮説の検討

| 仮説1: アディクションの「病

理化」は欧米的生物医療モデ

ルの輸入である |

仮説2: 心理的・社会的要因は

グローバル不均衡と密接に関

係している |

仮説3: 文化的意味は「アディクション」概念とずれている |

仮説4: 学術研究者の言説も脱

植民地的視点を欠いている |

仮説5: 「アディクション」は

ポストコロニアル的支配の言

説的装置である |

| 内容:ラテンアメリカにおけ

るアディクション(例:宗教

依存やインターネット依存)

は、欧米のDSM(精神障害の

診断と統計マニュアル)やICD

などの枠組みに従って「病理

化」されるが、これは必ずし

も地域文化的理解や経験に即

していない。 |

内容:(左と同じ) |

内容:ラテンアメリカでは、

宗教やインターネットの使用

が個人のアイデンティティや

社会的包摂の手段であるた

め、欧米的な「依存」として

の理解は、現地の文化的意味

と乖離している。 |

内容:ラテンアメリカのアデ

ィクション研究は、多くの場

合欧米の研究枠組みに従属し

ており、現地の文化的意味や

主体的実践を十分に取り入れ

ていない。 |

内容:依存行動の診断や介入

が、実際には「望ましい市

民」「合理的な個人」の形成

という新自由主義的/植民地

主義的プロジェクトの一部と

して機能している可能性があ

る。 |

| 背景:欧米の精神医学的モデ

ルが、ローカルな宗教実践

(例:ペンテコステ運動への

熱狂的信仰)やテクノロジー

使用の意味を「逸脱」として

ラベリングする可能性。 |

背景:社会的支援や未来への

希望が欠如しているため、宗

教共同体やバーチャル空間が

一種の「癒し」と「つなが

り」を提供。 |

背景:例えば、シャーマニズ

ム的儀礼や霊的トランス、あ

るいはSNSを通じた自己表現

は、自己治癒や社会参画と解

釈されることもある。 |

背景:たとえば、インターネ

ット依存に関する研究では、

使用時間や脳機能への影響ば

かりに注目し、なぜ若者がそ

れを求めるのかという文化

的・社会的背景が無視され

る。 |

背景:「過剰な信仰」や「非

生産的なテクノロジー使用」

は、支配的な社会秩序に従属

させるための規律として位置

づけられる。 |

☆依存症を文明論的視点から研究する着眼点は4つあ る。

★ 依存症を文明論的に解釈した研究というものがありますか?海外の研究でもかまいません。また文献を教えてください。(生成AI-Monica に聞く)

| 推論プロセス(1秒) |

まず、ユーザーが求めているのは「依存症を文明論的に解釈した研究」

の存在確認と関連文献の紹介です。文明論的なアプローチとは、社会構造、文化的価値観、技術の発展など、広範な文明的要素と依存症の関係を分析するものと

考えられます。 最初に、このテーマに関連する学術分野を特定します。社会学、文化人類学、哲学、メディア研究などが該当するでしょう。例えば、ジグムント・バウマンの 「リキッド・モダニティ」は現代社会の流動性と個人の不安定さを論じており、依存症との関連が考えられます。 次に、具体的な研究者や著作を挙げます。マーシャル・マクルーハンのメディア論は技術が人間の認知に与える影響を論じ、デジタル依存症の文脈で引用され ることがあります。また、バイオポリティクスの観点からミシェル・フーコーの研究も参照可能です。 さらに、現代のデジタル依存症に焦点を当てた研究も探します。Sherry Turkleの「Alone Together」やAdam Alterの「Irresistible」はテクノロジーと依存の関係を文明論的に分析しています。これらの文献は具体的な事例を交えつつ理論的枠組みを 提供しているため、ユーザーの要望に合致すると判断できます。 最後に、学術データベースやGoogle Scholarでの検索方法を簡潔にアドバイスし、ユーザーが自主的に調査を進められるように配慮します。また、検索機能の有効化を促すことで、より最新 の研究にアクセスできる可能性を |

| 推論の結果のアナウンス |

依存症を文明論的視点から分析する研究は、社会学・哲学・文化人類学の

領域で展開されています。主要なアプローチと代表文献をご紹介します。 |

| I. 近代文明と依存症の構造的関係 |

1. ジグムント・バウマン『リキッド・モダニティ』 液体化する現代社会 液体化する現代社会において、不安定なアイデンティティ形成が物質依存を促進するメカニズムを解明。消費社会の「瞬間的満足」の追求が依存症の土壌を形成 すると指摘。 2. ミシェル・フーコー『監視と処罰』 近代の規律権力が生み出す「自己管理」の強制が、逸脱行動としての依存症を病理化する過程を分析。管理社会における「正常/異常」の境界線の政治性に着 目。 |

| II. テクノロジー文明と新たな依存形態 |

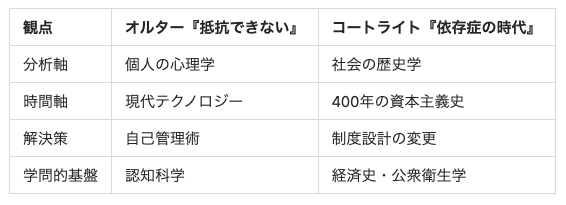

3. Sherry Turkle『Alone

Together』(『繋がっているのに孤独』) デジタル環境が人間関係を再構築する中で生まれる「擬似充足」のメカニズムを実証研究。SNS依存を「空虚を埋める擬似触覚」と表現。 4-1. Adam Alter『Irresistible』/ 僕らはそれに抵抗できない : 「依存症ビジネス」のつくられかた / アダム・オルター著 ; 上原裕美子訳, ダイヤモンド社 , 2019 行動経済学的手法でテック企業が意図的に設計する「依存性インターフェース」を暴露。通知機能や無限スクロールの神経科学的基盤を解明。 ++++++++++++++++++++++++++ プロローグ:「自分の商品でハイになるな」 第1部 新しい依存症「行動嗜癖」とは何か ・1. 物質依存から行動依存へ—新しい依存症の誕生 ・2. 僕らはみんな依存症—何が人を依存させるのか ・3. 愛と依存症の共通点—「やめたいのにやめられない」の生理学 第2部 新しい依存症が人を操る6つのテクニック ・4. 目標—ウェアラブル端末が新しいコカインに ・5. フィードバック—「いいね!」というスロットマシンを回しつづけてしまう理由 ・6. 進歩の実感—スマホゲームが心をわしづかみにするのは、“デザイン”のせい ・7. 難易度のエスカレート——テトリスが病的なまでに魅力的なのはなぜか ・8. クリフハンガー——ネトフリックスが僕たちに植えつけた恐るべき悪癖 ・9. 社会的相互作用——インスタグラムが使う「比較」という魔法 第3部 新しい依存症に立ち向かうための3つの解決策 ・10. 予防はできるだけ早期に—1歳から操作できるデバイスから子どもを守る ・11. 行動アーキテクチャで立ち直る—「依存症を克服できないのは意志が弱いから」は間違い ・13. ゲーミフィケーション—依存症ビジネスの仕掛けを逆手にとって悪い習慣を捨てる エピローグ まだ見ぬ「未来の依存症」から身を守るために ++++++++++++++++++++++++++ (1). 現代の「中毒」の正体 中毒=物質依存+行動依存 伝統的物質依存:アルコール/薬物 現代的行動依存:通知/いいね/無限スクロール (2). 中毒を生む6つの心理トリガー 目標の設定(ゲーミフィケーション) 進捗の可視化(プログレスバー) 予測不可能な報酬(スロットマシン効果) 社会的承認(いいね経済) エンドレスコンテンツ(自動再生機能) 操作の簡便性(ワンタップ操作) (3). テック企業の「依存デザイン」 行動デザインの3段階: エンゲージメント最大化 ユーザー行動の予測 報酬システムの最適化 4-2. 依存症ビジネス : 「廃人」製造社会の真実 / デイミアン・トンプソン著 ; 中里京子訳, ダイヤモンド社 , 2014 もはや病気ではない。最強最悪のビジネスモデルである。iPhone、フラペチーノ、危険ドラッグ、お酒、フェイスブック、アングリーバード、オンライン ポルノ…私たちは、なぜこうも簡単に「病みつき」になるのか?元アルコール依存症のライターが、人間の意志の弱さにつけ込むテクノロジーとビジネスの共犯 関係に迫る! 第1章 社会は私たちを「廃人」にしたがっている—iPhoneいじりと甘すぎるスイーツに見る病みつきビジネス 第2章 依存症は本当に“病気”なのか?—環境次第でだれもが「依存者」になりうる社会 第3章 なぜ自分を破滅に導く習慣をやめられないのか?—病みつきビジネスが利用している脳の仕組み 第4章 お買い物とヘロインとお酒の共通点とは?—自由市場と依存の関係は18世紀ロンドンで始まった 第5章 スイーツはもはやコカインだ!—スタバの「フラペチーノ」に仕込まれた巧妙な戦略 第6章 どこに行っても安く、大量に酒が手に入る世界で—社会をアルコール漬けにするメーカーと販売網 第7章 処方箋薬がこれほどいい加減とは!—合法的なおクスリでもじゅうぶントベる 第8章 ゲームという新時代のギャンブル—合言葉は「ユーザーを永遠のキャッシュマシンに!」 第9章 「無料ポルノ革命」の衝撃—最新テクノロジーを最大限に活かす無秩序な業界とその餌食たち 第10章 われらを誘惑から救いたまえ—依存の「解毒」ですら商売になる時代で |

| III. 資本主義システムとの共犯関係 |

5. David T. Courtwright『The Age

of Addiction』 産業革命以降の資本主義が「依存ビジネスモデル」を体系化した歴史を追跡。タバコ・アルコールからデジタルサービスまで続く「快楽の産業化」を論証。著 者は、フロリダ大学名誉教授。専門はアメリカ史と薬物史。前著『Forces of Habit』で精神活性物質のグローバル流通を分析した経歴を持つ。[資本主義と中毒性商品の共進化]をライフワークとして研究。

6. Carl Erik Fisher『The Urge』 依存症を「文明の影」として位置付け、古代の儀式的薬物使用から現代のゲーミフィケーションまでを貫く「陶酔への衝動」の文化史を構築。 The urge : our history of addiction/ 依存症と人類 : われわれはアルコール・薬物と共存できるのか, カール・エリック・フィッシャー [著] ; 小田嶋由美子訳, みすず書房 2023.4 |

| IV. 代替理論的アプローチ |

7. Gabor Maté『In the Realm of

Hungry Ghosts: close encounters with addiction』 トラウマ理論に基づき、現代社会の「関係性の貧困」が 依存症を生み出すメカニズムを神経科学的に解明。資本主義的個人主義の病理化を批判。 8. Bruce K. Alexander『The Globalization of Addiction』 「ディスロケーション理論」を提唱。新自由主義的グローバリゼーションがもたらす社会的紐帯の解体が依存症蔓延の根本原因と指摘。 |

| 研究手法の提案 |

1. JSTORやGoogle

Scholarで以下のキーワード検索: "civilization and addiction" "sociology of dependency" "cultural pathology of modernity" 2. 学際的ジャーナル: Addiction Research & Theory Journal of Medical Humanities Philosophy, Psychiatry, & Psychology |

| まとめ |

文明論的視点と依存症研究の交叉領域では、特に2010年代以降のデジ

タルテクノロジー関連の研究が急増している状況です。 |

★資本主義の発達と、当該の地域での依存症者の件数の増加は関係しているでしょうか?(ChatGPT5.0に聞いてみた)→「資本主義と依存症」に移転します

☆ 人類史にとって依存症とはどんな意味がありますか?とGemini に聞いてみました。

| 人類史にとって依存症とはどんな意味がありま すか?とGemini に聞いてみました | 人類史にとって依存症とはどんな意味がありますか? |

| 人類史において、依存症は様々な意味合いを持ち、社会や文化、個人の生

活に深く関わってきました。その意味合いは多岐にわたりますが、主な点を挙げると以下のようになります。 |

|

| 1. 生存と進化の側面 |

・

報酬系の進化と現代社会のミスマッチ:

人間の脳には、生存に必要な行動(食事、生殖、学習など)を促すための「報酬系」と呼ばれる神経回路があります。これは、満足感や快感を与えることで、そ

の行動を繰り返させようとする仕組みです。しかし、現代社会では、高カロリーの食品、アルコール、薬物、インターネット、ギャンブルなど、報酬系を強く刺

激するものが簡単に手に入ります。進化の過程で「ストッパー」を持たなかった人間は、これらの過剰な刺激に対して制御が効きにくく、依存症に陥りやすいと

いう側面があります。 ・ストレス対処: 依存性のある物質や行動は、一時的にストレスや不安を和らげる効果があるため、古くから人類はそれらを利用してきました。しかし、それが習慣化し、問題解 決能力の低下や精神状態の悪化を招くことがあります。 |

| 2. 社会的・文化的側面 |

・

社会問題としての認識の変遷:

古代文明の時代からアルコールなどの乱用は存在し、酩酊や暴飲に関する記述が残っています。中世から近代にかけて蒸留酒が普及すると、アルコール依存がさ

らに社会問題化しました。現代では、薬物依存、ギャンブル依存に加え、インターネットやスマートフォンへの依存など、その対象は多様化し、新たな社会問題

として認識されています。 ・スティグマと差別: 依存症は、個人の意思の弱さや道徳的な問題とみなされ、社会的なスティグマ(偏見や差別)を伴うことが多くありました。これにより、依存症に苦しむ人々は 適切な支援を受けられず、孤立を深める傾向がありました。 ・文化と宗教における役割: 過去には、特定の中毒者がシャーマン的な霊的な存在として尊敬を集めたこともあったようです。また、アルコールなどの物質が宗教儀式や社会的な交流の場で 用いられるなど、文化や宗教に深く根付いていた時期もあります。 ・経済的影響: 依存症は、飲酒運転、失業、医療費の増大など、個人だけでなく社会全体に大きな経済的損失をもたらします。 |

| 3. 医学的・科学的理解の深化 |

・病気としての認識:

かつて「中毒」と呼ばれていた依存症は、1980年代以降、精神科医療の分野でより正確で広範な意味を含む「アディクション」という言葉に置き換えられ、

慢性疾患としての側面が認識されるようになりました。 ・脳科学の進展: 報酬系の機能不全や脳の構造的変化など、依存症の生物学的メカニズムが解明されつつあります。これにより、依存症に対する理解が深まり、より効果的な治療 法の開発につながっています。 |

| まとめ |

依

存症は、単なる個人の問題ではなく、人類の進化、社会の変遷、文化、そして科学技術の発展と密接に結びついています。人類史において、依存症は快楽やスト

レス解消の手段として存在し続けた一方で、個人と社会に多大な負の影響をもたらしてきました。その歴史的経緯と現代の理解を通じて、依存症は、人間と欲

求、そして社会との関係性を深く問い直す重要なテーマであると言えます。 |

| 依存症と経済の研究 |

依存症と経済の関係に関する研究は、主に以下の4つの領域で進展が見ら

れます。行動経済学と神経経済学の融合研究が近年特に注目されています。 1. 経済的損失の定量化研究 ・米国国立薬物乱用研究所(NIDA)の2023年報告書によると、物質使用障害による米国経済への年間損失は約1.2兆ドル ・1.2兆ドル(GDPの5.4%相当) ・生産性低下(56%)、医療費(26%)、刑事司法関連費用(18%)の内訳 ・間接費用として家族の介護負担や世代間連鎖の経済影響を含む新たな計測手法が開発中 2. 社会経済的要因の影響分析 ・失業率1%上昇ごとにアルコール依存症罹患率が0.8−1.2増加(WHO 2022) ・所得格差(ジニ係数)とギャンブル依存症の相関(r=0.67)を示す国際比較研究 ・都市部の「食料砂漠」地域におけるジャンクフード依存と経済困窮の双方向関係 3. 行動経済学的介入手法 ・ナッジ理論を応用した予防プログラム(例:貯蓄ボーナス付き禁煙プログラム) ・プレコミットメントデバイスの開発(将来の選択を事前に制限するスマート契約) ・行動経済学的フレーミング効果を利用した治療促進策 4. 神経経済学的最新知見 ・fMRI研究で明らかになった意思決定プロセスの神経基盤 ・前頭前皮質の活性低下(β波30%減)と衝動的行動の関連 ・報酬予測誤差信号(ドーパミン放出)の過敏化現象 ・神経経済モデルを用いた個別化治療アプローチの開発動向 主要論文例: - Becker & Murphy (1988) "A Theory of Rational Addiction"(合理的意思決定モデル) - Volkow et al. (2019) "Neuroeconomic Advances in Addiction Research"(神経経済学アプローチ) - Ruhm (2023) "Macroeconomic Conditions and Opioid Abuse"(景気変動とオピオイド危機) 研究手法として近年はビッグデータ分析(クレジットカード決済データ×健康記録の紐付け)やAIシミュレーションモデルの活用が増加傾向にあります。経済 学・医学・情報科学の学際的研究が今後の鍵となる分野です。 |

| 「依存症ビジネス」は日本語のジャーゴンか? |

「依 存症ビジネス」というタイトルがついた本は2冊の邦訳があるが、ともにオリジナルタイトルにそのような英語の用語はない。(1) 依存症ビジネス : 「廃人」製造社会の真実 / デイミアン・トンプソン著 ; 中里京子訳, ダイヤモンド社 , 2014./ Damian Thompson, The Fix: How Addiction Is Invading our Lives and Taking Over Your World. Collins, 2012. (2) Irresistible : the rise of addictive technology and the business of keeping us hooked, Adam Alter, [Penguin Press (2017/3/7)] 2018/ 僕らはそれに抵抗できない : 「依存症ビジネス」のつくられかた / アダム・オルター著 ; 上原裕美子訳 |

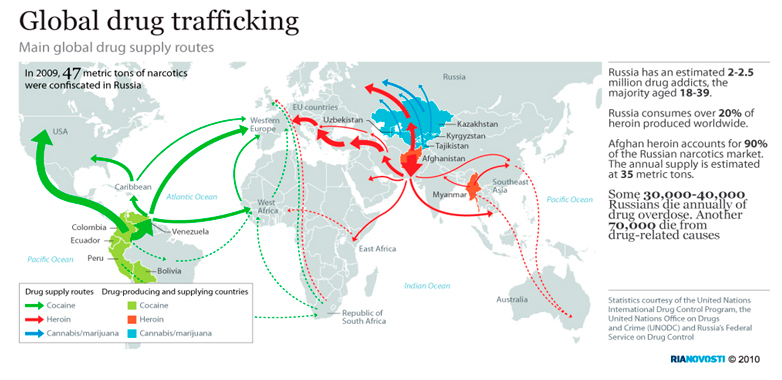

★ドラッグの世界流通と宗教(ペンテコステ運動)の布教の形態的類似性

★ The Fix: How Addiction Is Invading our Lives and Taking Over Your Worldをめぐる論争

| The Rise of Behavioral Addiction A couple of years ago, Kevin Holesh, an app developer, decided that he wasn’t spending enough time with his family. The culprit was technology, and his smartphone was the biggest offender. Holesh wanted to know how much time he was spending on his phone each day, so he designed an app called Moment. Moment tracked Holesh’s daily screen time, tallying how long he used his phone each day. I spent months trying to reach Holesh because he lives by his word. On the Momentwebsite, he writes that he may be slow to reply to email because he’s trying to spend less time online. Eventually, after my third attempt, Holesh replied with a polite apology and agreed to talk. “The app stops tracking when you’re just listening to music or making phone calls,” Holesh told me. “It starts up again when you’re looking at your screen—sending emails or browsing the web, for example.” Holesh was spending an hour and fifteen minutes a day glued to his screen, which seemed like a lot. Some of his friends had -similar concerns, but also had no idea how much time they lost to their phones. So Holesh shared the app. “I asked people to guess what their daily usage was and they were almost always 50 percent too low.” I downloaded Moment several months ago. I guessed I was using my phone for an hour a day at the most, and picking it up perhaps ten times a day. I wasn’t proud of those numbers, but they sounded about right. After a month, Moment reported that I was using my phone for an average of three hours a day, and picking it up an average of forty times. I was stunned. I wasn’t playing games or surfing the web for hours, but somehow I managed to spend twenty hours a week staring at my phone. I asked Holesh whether my numbers were typical. “Absolutely,” he said. “We have thousands of users, and their average usage time is just under three hours. They pick up their phones an average of thirty-nine times a day.” Holesh reminded me that these were the people who were concerned enough about their screen time to download a tracking app in the first place. There are millions of smartphone users who are oblivious or just don’t care enough to track their usage—and there’s a reasonable chance they’re spending even more than three hours on their phones each day. Perhaps there was just a small clump of heavy users who spent all day, every day on their phones, dragging the average usage times higher. But Holesh shared the usage data of eight thousand Moment users to illustrate that wasn’t the case at all: Most people spend between one and four hours on their phones each day—and many far longer. This isn’t a minority issue. If, as guidelines suggest, we should spend less than an hour on our phones each day, 88 percent of Holesh’s users were overusing. They were spending an average of a quarter of their waking lives on their phones—more time than any other daily activity, except sleeping. Each month almost one hundred hours was lost to checking email, texting, playing games, surfing the web, reading articles, checking bank balances, and so on. Over the average lifetime, that amounts to a staggering eleven years. On average they were also picking up their phones about three times an hour. This sort of overuse is so prevalent that researchers have coined the term “nomophobia” to describe the fear of being without mobile phone contact (an abbreviation of “no-mobile-phobia”). Smartphones rob us of time, but even their mere presence is damaging. In 2013, two psychologists invited pairs of strangers into a small room, and asked them to engage in conversation. To smooth the process, the psychologists suggested a topic: why not discuss an interesting event that happened to you over the past month? Some of the pairs talked while a smartphone sat idle nearby, while for others the phone was replaced by a paper notebook. Every pair bonded to some extent, but those who grew -acquainted in the presence of the smartphone struggled to connect. They described the relationships that formed as lower in quality, and their partners as less empathetic and trustworthy. Phones are disruptive by their mere existence, even when they aren’t in active use. They’re distracting because they remind us of the world beyond the immediate conversation, and the only solution, the researchers wrote, is to remove them completely. Smartphones aren’t the only culprits. Bennett Foddy has played thousands of video games, but refuses to play World of Warcraft. Foddy is a brilliant thinker with dozens of interests. He works as a game developer and professor at New York University’s Game Center. Foddy was born and lived in Australia, where he was the bassist in an Australian band called Cut Copy—which released several best-selling singles and won a string of Australian music awards—until he moved, first to Princeton University and then to Oxford University, to study -philosophy. Foddy has immense respect for WoW, as it’s known, but won’t play it himself. “I take it as part of my job to play all the culturally significant games. But I didn’t play that one because I can’t afford the loss of time. I know myself reasonably well, and I suspect it probably would have been difficult for me to shake.” WoW may be one of the most addictive behavioral experiences on the planet. It’s a massively multiplayer online -role--playing game, with millions of players from around the world who create avatars that roam across landscapes, fight monsters, complete quests, and interact with other players. Half of all players -consider themselves “addicted.” An article in Popular Science described WoW as “the obvious choice” when searching for the world’s most addictive game. There are support groups with thousands of members, and more than a quarter of a million people have taken the free online World of Warcraft Addiction Test. In ten years, the game has grossed more than ten billion dollars, and attracted more than one hundred million -subscribers. If they formed a nation, it would be the twelfth biggest on Earth. WoW players choose an avatar, which represents them as they complete quests in a virtual world called Azeroth. Many players band together to form guilds—teams of allied avatars—which is part of what makes the game so addictive. It’s hard to sleep at night when you know three of your guild-mates in Copenhagen, Tokyo, and Mumbai are on an epic quest without you. As we chatted, I was struck by Foddy’s passion for games. He believes without a doubt that they’re a net force for good in the world—but still refuses to sample the charms of Azeroth for fear of losing months or years of his life. Games like WoW attract millions of teens and young adults, and a considerable minority—up to 40 percent—develop addictions. Several years ago a computer programmer and a clinical psychologist joined forces to open a gaming and Internet -addiction center in the woods near Seattle. The center, named -reSTART, houses a dozen or so young men who are addicted to WoW, or one of a handful of other games. (reSTART tried admitting a small group of women, but many Internet addicts also develop sex addictions, so cohabitation became a major distraction.) Computers have never before had the memory to run games like WoW, which are much faster, more immersive, and less clunky than the games of the twentieth century. They allow you to interact with other people in real time, a huge part of what makes them so addictive. Technology has also changed how we exercise. Fifteen years ago I bought an early model Garmin exercise watch, a mammoth rectangular device somewhere between a watch and a wrist weight. It was so heavy that I had to carry a water bottle in my other hand to balance its weight. It lost its GPS signal every couple of minutes, and battery life was so limited that it was useless on long runs. Today there are cheaper, smaller wearable devices that capture every step. That’s miraculous, but also a recipe for obsession. Exercise addiction has become a psychiatric specialty because athletes are constantly reminded of their activity and, even more so, their inactivity. People who wear exercise watches become trapped in a cycle of escalation. Ten thousand steps may have been the gold standard last week, but this week it’s eleven thousand. Next week, twelve thousand, and then fourteen thousand. That trend can’t continue forever, but many people push through stress fractures and other major injuries to seek the same endorphin high that came from a much lighter exercise load only months earlier. Intrusive tech has also made shopping, work, and porn harder to escape. It was once almost impossible to shop and work between the late evening and early morning, but now you can shop online and connect to your workplace any time of the day. Gone also are the days of stealing a copy of Playboy from the newsstand; all you need are Wi-Fi and a web browser. Life is more convenient than ever, but convenience has also weaponized temptation. So how did we get here? The first “behavioral addicts” were two-month-old babies. In early December 1968, forty-one psychologists who studied human vision met in New York City at the annual meeting of the Association for Research in Nervous and Mental Disease to -discuss why our ability to see sometimes fails. It was a who’s who of academic luminaries. Roger Sperry would win the Nobel Prize in medicine thirteen years later. Neuroscientist Wilder Penfield was once described as the “greatest living Canadian,” and Stanford’s William Dement was crowned “the father of sleep medicine.” In attendance was the psychologist Jerome Kagan, who a decade earlier had joined Harvard University to create the first program in human development. By his retirement half a century later, he was listed as the twenty-second most eminent psychologist of all time—ahead of giants like Carl Jung, Ivan Pavlov, and Noam Chomsky. At the meeting, Kagan discussed visual attention in infants. How, he asked, do two-month-old babies know what to look at and what to ignore? Their growing brains are bombarded by a kaleidoscope of visual information, and yet somehow they learn to focus on some images and look past others. Kagan noticed that very young babies were drawn to moving, hard-edged objects. In fact, they couldn’t look away when a researcher dangled a wooden block before them. According to Kagan, these infants were showing “a behavioral addiction to contour and movement.” By modern standards, though, it would be a stretch to call the infants behavioral addicts. Kagan was right that they couldn’t look away, but the way we think of behavioral addiction today is quite different. It’s more than an instinct that we can’t override, because that would include blinking and breathing. (Try holding your breath till you pass out and your brain will eventually force you to breathe again.) The fact that we can’t help inhaling and exhaling means we’re unlikely to die from forgetting to breathe. Modern definitions recognize that addiction is ultimately a bad thing. A behavior is addictive only if the rewards it brings now are eventually outweighed by damaging consequences. Breathing and looking at wooden blocks aren’t addictive because, even if they’re very hard to resist, they aren’t harmful. Addiction is a deep attachment to an experience that is harmful and difficult to do without. Behavioral addictions don’t involve eating, drinking, injecting, or smoking substances. They arise when a person can’t resist a behavior, which, despite addressing a deep psychological need in the short-term, produces significant harm in the long-term. Obsession and compulsion are close relatives of behavioral -addiction. Obsessions are thoughts that a person can’t stop having, and compulsions are behaviors a person can’t stop enacting. There’s a key difference between addictions, and obsessions and compulsions. Addictions bring the promise of immediate reward, or positive reinforcement. In contrast, obsessions and -compulsions are intensely unpleasant to not pursue. They promise relief—-also known as negative reinforcement—but not the appealing -rewards of a consummated addiction. (Since they’re so closely related, I’ll use all three terms in this book.) Behavioral addiction also has a third relative in obsessive passion. In 2003, seven Canadian psychologists, led by the researcher Robert Vallerand, wrote a paper splitting the concept of passion in two. “Passion,” they said, “is defined as a strong inclination toward an activity that people like, that they find important, and in which they invest time and energy.” Harmonious passions are very healthy activities that people choose to do without strings attached—the model train set that an elderly man has been working on since his youth, or the series of abstract paintings that a middle-aged woman creates in her free time. “Individuals are not compelled to do the activity,” the researchers said, “but rather they freely choose to do so. With this type of passion, the activity occupies a significant but not overwhelming space in the person’s identity and is in harmony with other aspects of the person’s life.” Obsessive passions, however, are unhealthy and sometimes dangerous. Driven by a need that goes beyond simple enjoyment, they’re likely to produce behavioral addictions. As the researchers defined it, the individual “cannot help but to engage in the passionate activity. The passion must run its course as it controls the person. Because activity engagement is out of the person’s control, it eventually takes disproportionate space in the person’s identity and causes conflict with other activities in the person’s life.” This is the video game that a teenager plays all night instead of sleeping and doing his homework. Or the runner who once ran for fun, but now feels compelled to run at least six miles a day at a certain pace, even as debilitating stress injuries set in. Until she’s on her back, unable to walk, she’ll continue to run daily because her identity and well-being are intimately bound with her as yet unbroken streak. Harmonious passions “make life worth living,” but an obsessive passion that goes unfulfilled distracts and plagues the mind. There are people, of course, who disagree with the idea that addictions can be purely behavioral. “Where are the substances?” they ask. “If you can be addicted to video games and smartphones, why can’t you be addicted to smelling flowers or walking backward?” You can be addicted to those things, in theory. If they come to fulfill a deep need, you can’t do without them, and you begin to pursue them while neglecting other aspects of your life, then you’ve developed a behavioral addiction to smelling flowers or walking backward. There probably aren’t many people with those particular addictions, but they aren’t inconceivable. Meanwhile, there are many, many people who show similar symptoms when you introduce them to a smartphone or a compelling video game or the concept of email. There are also people who say that the term “addiction” can’t possibly apply to a majority of the population. “Doesn’t that devalue the term ‘addiction’? Doesn’t that make it meaningless and empty?” they ask. When, in 1918, a flu pandemic killed seventy-five million people, no one suggested that a flu diagnosis was meaningless. The issue demanded attention precisely because it affected so many people, and the same is true of behavioral addiction. Smartphones and email are hard to resist—because they’re both part of the fabric of society and promote psychologically compelling experiences—and there will be other addictive experiences in the coming decades. We shouldn’t use a watered-down term to describe them; we should acknowledge how serious they are, how much harm they’re doing to our collective well-being, and how much attention they deserve. The evidence so far is concerning, and trends suggest we’re wading deeper into dangerous waters. |

行動依存症の台頭 数年前、アプリ開発者のケビン・ホレスは家族と過ごす時間が足りないと感じた。原因はテクノロジー、特にスマートフォンだった。ホレスは自分が1日にスマ ホをどれだけ使っているか知りたく、そこで「モーメント」というアプリを開発した。モーメントはホレスの毎日のスクリーンタイムを記録し、1日のスマホ使 用時間を計測した。私は数か月かけてホレスに連絡を取ろうとした。彼は約束を守る人間だからだ。モーメントのウェブサイトには「オンライン時間を減らすた め、メール返信が遅れることがある」と書かれている。三度目の試みでようやく返事が来た。丁寧な謝罪と共に、彼は取材に応じることを承諾した。「音楽を聴 いたり電話をしている時は、アプリは計測を停止する」とホレスは説明した。「画面を見ている時、例えばメールを送ったりウェブを閲覧したりすると、再び計 測が始まるんだ」。ホレスは1日1時間15分も画面に釘付けになっていた。これはかなり長い時間だ。彼の友人たちにも同様の懸念はあったが、スマホにどれ ほどの時間を奪われているか全く把握していなかった。そこでホレスはこのアプリを共有した。「人々1日のスマホ使用時間を推測してもらったら、ほぼ例外な く実際の半分以下だった」 数ヶ月前、私もモーメントをダウンロードした。1日せいぜい1時間、手に取る回数も10回程度だろうと推測した。この数字は自慢できるものではなかった が、まあ妥当だろうと思っていた。一ヶ月後、モーメントは私の平均使用時間が一日三時間、平均操作回数が四十回だと報告した。私は呆然とした。ゲームに没 頭したりネットサーフィンに時間を費やしたりしていたわけではないのに、どういうわけか一週間に二十時間もスマホを凝視していたのだ。 この数値が平均的かホーレスに尋ねると「間違いなくそうだ」と答えた。「数千人のユーザーがいるが、平均使用時間は3時間弱だ。1日平均39回スマホを手 に取っている」と。ホーレスは、そもそもこうした数値を気にして追跡アプリをダウンロードする人々が対象だと指摘した。何百万ものスマホユーザーは、自分 の使用時間を追跡することすら気づいていないか、あるいは気にかけていない。そして彼らは1日3時間以上スマホを使っている可能性が十分にある。 おそらく、1日中スマホに没頭するヘビーユーザーがごく一部存在し、平均使用時間を押し上げているだけかもしれない。しかしホレスは8000人のモーメントユーザーの使用データを示し、そうではないことを明らかにした: 大半の人民は1日1~4時間をスマホに費やしている。さらに長い時間も珍しくない。これは少数派の問題ではない。ガイドラインが推奨する「1日1時間未 満」という基準を適用すれば、ホレスのユーザーのうち88%が過剰使用状態だ。彼らは起きている時間の4分の1をスマホに費やしており、睡眠を除けば他の 日常活動よりも長い時間である。メール確認、メッセージ送信、ゲーム、ネット閲覧、記事読解、残高確認などに毎月約100時間を浪費していた。平均寿命で 換算すると驚異的な11年に相当する。さらに平均して1時間に約3回もスマートフォンを手に取っていた。この種の過剰使用は極めて普遍的であり、研究者ら は携帯電話との接触が途絶えることへの恐怖を表現する「ノモフォビア」(「no-mobile-phobia」の略語)という用語を考案した。 スマートフォンは時間を奪うだけでなく、その存在自体が有害だ。2013年、二人の心理学者は見知らぬ者同士を小さな部屋に招き、会話を交わすよう依頼し た。会話の流れを円滑にするため、心理学者は話題を提案した。「この1ヶ月で起きた面白い出来事を話し合ってみては?」と。一部のペアはスマートフォンが 傍らに置かれた状態で話し、別のペアではスマートフォンが紙のノートに置き換えられた。どのペアもある程度親密になったが、スマートフォンの存在下で知り 合ったペアは心の繋がりに苦労した。彼らは形成された関係を質が低いと表現し、相手を共感力や信頼性に欠けると評価した。スマートフォンは、たとえ使用中 でなくても、その存在自体が妨げとなる。目の前の会話以外の世界を思い出させるため気が散るのだ。研究者らは、唯一の解決策はスマートフォンを完全に排除 することだと記している。 スマートフォンだけが原因ではない。ベネット・フォディは数千ものビデオゲームをプレイしてきたが、『World of Warcraft』だけはプレイを拒んでいる。フォディは数十の分野に精通する卓越した思想家だ。ニューヨーク大学ゲームセンターでゲーム開発者兼教授を 務める。オーストラリア生まれで、移住前は同国のバンド「カット・コピー」のベーシストとして活動。同バンドは複数のベストセラーシングルをリリースし、 数々のオーストラリア音楽賞を受賞した。その後プリンストン大学、オックスフォード大学で哲学を学んだ。フォディは通称「WoW」と呼ばれるこのゲームを 深く尊敬しているが、自らプレイすることはない。「文化的に重要なゲームは全てプレイするのが仕事の一部だ。だがあのゲームだけはプレイしなかった。時間 を浪費する余裕がなかったからだ。自分のことはそこそこ分かっている。おそらくやめられなくなるだろうと察していた」 WoW, World of Warcraftは 地球上で最も中毒性の高い体験の一つかもしれない。これは大規模多人数参加型オンラインロールプレイングゲームであり、世界中の何百万ものプレイヤーがア バターを作成し、広大な土地を歩き回り、モンスターと戦い、クエストをクリアし、他のプレイヤーと交流する。全プレイヤーの半数が自らを「中毒」と認めて いる。『ポピュラーサイエンス』誌の記事は、世界で最も中毒性の高いゲームを探す際、WoWを「明らかな選択肢」と評した。数千人のメンバーを抱える支援 グループが存在し、25万人以上が無料のオンライン「World of Warcraft依存症診断テスト」を受験している。10年間でこのゲームは100億ドル以上の収益を上げ、1億人以上の加入者を集めた。もし彼らが一つ の国民を形成すれば、地球上で12番目に大きな国民となるだろう。WoWプレイヤーはアバターを選択し、アゼロスと呼ばれる仮想世界でクエストを達成す る。多くのプレイヤーはギルド——同盟アバターのチーム——を結成する。これがゲームの中毒性を高める一因だ。コペンハーゲン、東京、ムンバイにいるギル ド仲間3人が自分抜きで壮大なクエストに挑戦していると知れば、夜も眠れない。話しているうちに、フォディのゲームへの情熱に驚かされた。彼はゲームが世 界に良い影響を与えると確信しているが、それでもアゼロスの魅力に触れることを拒んでいる。何ヶ月も何年も人生を浪費する恐れがあるからだ。 『WoW』のようなゲームは数百万の10代や若者を惹きつけるが、かなりの少数派——最大40パーセント——が依存症を発症する。数年前、コンピューター プログラマーと臨床心理士が協力し、シアトル近郊の森の中にゲーム・インターネット依存症治療センターを開設した。reSTARTと名付けられたこの施設 には、WoWやその他数種類のゲームに依存する十数名の若者が収容されている。(reSTARTは少数の女性も受け入れたが、インターネット依存症患者の 多くは性依存症も併発するため、共同生活は大きな妨げとなった。) コンピューターはかつて、『WoW』のようなゲームを動かす記憶容量を持たなかった。20世紀のゲームよりはるかに高速で没入感が高く、動作も滑らかだ。 リアルタイムで他者と交流できる点が、中毒性を高める大きな要因となっている。 テクノロジーは運動方法も変えた。15年前、私は初期モデルのガーミン製運動用ウォッチを購入した。時計とリストウェイトの中間のような巨大な長方形の装 置だった。重すぎて、バランスを取るために片手に水筒を持たねばならなかった。数分おきにGPS信号を失い、バッテリー持続時間が短すぎて長距離走には使 えなかった。今では安価で小型のウェアラブルデバイスが歩数を計測する。これは奇跡的だが、同時に執着を生む要因でもある。運動依存症が精神医学の専門分 野となったのは、アスリートが自身の活動量、そして何よりも不活動量を常に意識させられるからだ。運動用ウォッチを装着する人民はエスカレーションのサイ クルに囚われる。先週は1万歩が基準だったのに、今週は1万1千歩。来週は1万2千歩、そして1万4千歩へと。この傾向は永遠に続かないが、多くの人々は ストレス骨折や重大な怪我を押し切って、ほんの数ヶ月前ならはるかに軽い運動量で得られたエンドルフィンの高揚感を追い求める。 侵入的なテクノロジーは、買い物や仕事、ポルノからも逃れにくくした。かつては深夜から早朝にかけて買い物や仕事をするのはほぼ不可能だったが、今では一 日中オンラインで買い物ができ、職場に接続できる。新聞スタンドからプレイボーイをこっそり買う時代も終わった。必要なのはWi-Fiとウェブブラウザだ けだ。生活はかつてないほど便利になったが、その便利さが誘惑を武器化したのだ。 では、なぜこうなったのか? 最初の「行動依存症患者」は生後2ヶ月の赤ん坊だった。1968年12月初旬、人間の視覚を研究する41人の心理学者がニューヨークで神経・精神疾患研究 協会の年次総会に集まり、視覚機能が時折機能不全に陥る理由を議論した。出席者は学界の著名人ばかりだった。ロジャー・スペリーは13年後にノーベル医学 賞を受賞する。神経科学者ワイルダー・ペンフィールドは「現存する最も偉大なカナダ人」と評され、スタンフォード大学のウィリアム・ディメントは「睡眠医 学の父」と称された。 出席者には心理学者ジェローム・ケイガンがいた。彼は10年前にハーバード大学に招かれ、人間発達学の最初のプログラムを創設した人物だ。半世紀後の引退 時には、史上22番目に著名な心理学者として名を連ねていた。カール・ユング、イワン・パブロフ、ノーム・チョムスキーといった巨匠たちをも凌ぐ評価だ。 会議でケイガンは乳児の視覚的注意について論じた。生後2ヶ月の赤ん坊は、何を見るべきか、何を無視すべきかをどうやって知るのか?成長中の脳は万華鏡の ような視覚情報に襲われるが、それでも何らかの方法で特定のイメージに集中し、他のものは無視することを学ぶ。カガンはごく幼い乳児が動く角張った物体に 引き寄せられることに気づいた。実際、研究者が木製のブロックを目の前で揺らすと、彼らは目を離せなかった。カガンによれば、これらの乳児は「輪郭と動き に対する行動的依存」を示していたという。 しかし現代の基準で言えば、乳児を行動依存症と呼ぶのは無理がある。カガンの言う通り彼らは目を離せなかったが、現代の行動依存症の概念は全く異なる。そ れは我々が抑制できない本能以上のものだ。なぜならそれはまばたきや呼吸も含むことになるからだ(息を止めて気絶するまで耐えてみろ。脳が最終的に呼吸を 強制する)。吸ったり吐いたりするのを止められないという事実は、呼吸を忘れたからといって死ぬ可能性が低いことを意味する。現代の定義では、依存症は究 極的には悪いものだと認識されている。ある行動が依存性を持つのは、それがもたらす即時的な報酬が、最終的には有害な結果によって上回られる場合だけだ。 呼吸や木製ブロックを見ることは依存性を持たない。たとえ非常に抵抗しがたくても、それらは有害ではないからだ。依存症とは、有害でありながら断つのが困 難な体験への深い執着である。行動依存症は、物質の摂取・飲酒・注射・喫煙を伴わない。短期的に深い心理的欲求を満たす一方で、長期的に重大な害をもたら す行動を、人格が抵抗できなくなった時に生じる。 強迫観念と強迫行為は行動依存症の近縁だ。強迫観念は止められない思考であり、強迫行為は止められない行動である。依存症と強迫観念・強迫行為には決定的 に異なる点がある。依存症は即時の報酬、つまり正の強化を約束する。一方、強迫観念と強迫行為は実行しないことが強烈に不快だ。それらは「救済」——いわ ゆる負の強化——をもたらすが、依存症が達成時に与える魅力的な報酬ではない。(これら三者は密接に関連しているため、本書では全て同じ用語で扱う。) 行動依存症には、強迫的な情熱という第三の近縁関係も存在する。2003年、ロバート・ヴァレランド研究者率いるカナダ人心理学者7名は、情熱の概念を二 分する論文を発表した。「情熱とは、人民が好む活動、重要と考える活動、時間とエネルギーを注ぐ活動への強い傾倒として定義される」と彼らは述べた。調和 的な情熱とは、人民が無償で自ら選ぶ健全な活動だ——老人が青年期から取り組む模型鉄道、中年女性が余暇に制作する抽象画シリーズなどである。「個人はそ の活動を強制されるのではなく、自ら進んで選択する」と研究者らは述べた。「この種の情熱では、活動は人格のアイデンティティにおいて重要な位置を占める が、圧倒的ではなく、人生の他の側面と調和している」 しかし強迫的な情熱は不健全で、時に危険だ。単純な楽しみを超えた欲求に駆られ、行動依存症を引き起こす可能性が高い。研究者らが定義するところでは、個 人は「情熱的な活動に従事せずにはいられない。情熱は人を支配し、その流れに身を任せるしかない。活動への没頭は本人の制御が及ばないため、最終的に個人 のアイデンティティの中で不釣り合いな存在感を増し、生活上の他の活動と衝突を引き起こす」のである。これは、十代の若者が睡眠や宿題を犠牲にして徹夜で プレイするビデオゲームだ。あるいは、かつては楽しみで走っていたランナーが、今では毎日少なくとも6マイルを一定のペースで走らねばならないと感じ、衰 弱させるストレス障害が生じても走り続けるケースだ。彼女が仰向けに寝たきりになり歩けなくなるまで、毎日走り続けるだろう。なぜなら彼女のアイデンティ ティと幸福感は、未だ途切れていない連続記録と密接に結びついているからだ。調和のとれた情熱は「生きる価値を人生に与える」が、満たされない執着的な情 熱は心を乱し苦しめる。 もちろん、依存症が純粋に行動に起因するとする考えに異論を唱える人民もいる。「物質はどこにあるんだ?」と彼らは問う。「ビデオゲームやスマートフォン に依存できるなら、花の香りを嗅ぐことや後ろ向きに歩くことに依存できない理由があるか?」 理論上は、そうしたものに依存することは可能だ。もしそれらが深い欲求を満たすようになり、それなしではいられなくなり、他の生活の側面を顧みずに追い求 めるようになれば、花の香りを嗅ぐことや後ろ向きに歩くことへの行動依存が生まれたことになる。そうした特定の依存症を持つ人民は、おそらく多くないが、 考えられないことではない。一方で、スマートフォンや魅力的なビデオゲーム、メールという概念を提示された時、同様の症状を示す人は非常に多い。 「中毒」という用語が大多数の人々に適用されるはずがないと主張する人々もいる。「それは『中毒』という言葉を軽んじているのではないか? 意味のない空虚なものにしてしまうのではないか?」と彼らは問う。1918年にインフルエンザのパンデミックが7500万人の命を奪った時、インフルエン ザの診断が無意味だなどと誰も言わなかった。問題が注目されたのは、まさに多くの人々に影響を与えたからだ。行動依存症についても同じことが言える。ス マートフォンやメールは抵抗しがたい。それらは社会の基盤の一部であり、心理的に強い体験を促すからだ。そして今後数十年で、他の依存性のある体験も現れ るだろう。それらを軽んじた言葉で表現すべきではない。その深刻さ、集団の幸福に与える害、そして注ぐべき注意の度合いを認めるべきだ。これまでの証拠は 憂慮すべきものであり、傾向は我々が危険な水域に深く足を踏み入れていることを示唆している。 |

| https://x.gd/VGa0L | |

| The fix : how addiction is invading our lives and taking over your world |

依存症ビジネス : 「廃人」製造社会の真実 / デイミアン・トンプソン著 ; 中里京子訳, ダイヤモンド社 , 2014. |

| The Fix: How Addiction Is Invading our Lives and Taking Over Your World

is a non-fiction book by the British writer and journalist Damian

Thompson in which Thompson examines addiction and how it is being

harboured in society. His fourth book, it was published in May 2012 by

Collins. Shortly after release, its core contention that addiction is

not a pathological disorder provoked controversy from left-wing

journalists. |

『フィックス:中毒が私たちの生活を侵食し、世界を支配する』は、英国

の作家兼ジャーナリスト、ダミアン・トンプソンによるノンフィクション作品である。トンプソンは本書で中毒現象と、それが社会に根付く仕組みを検証してい

る。彼の四冊目の著作であり、2012年5月にコリンズ社より刊行された。発売直後、中毒は病理的な障害ではないという核心的主張が、左派系ジャーナリス

トらから論争を巻き起こした。 |

| Overview In addition to his research, the book is informed by Thompson's experience as a former alcoholic and his participation in the Alcoholics Anonymous Twelve-Step sobriety program.[1]: 33–37 He rejects the brain disease theory of addiction (an example of which is disease theory of alcoholism), arguing that addiction is instead a voluntary and reversible behavioural disorder based on the brain's reward system, namely the mesolimbic pathway. Thompson argues that addiction is universally being fostered by technology and the social environment for commercial purposes, pointing to sugar addiction from sugar-rich foods such as cupcakes, addictions to pornography, video games, shopping, and drugs such as alcohol, caffeine; illegal drugs such as cocaine and heroin, and controlled medical drugs — such as zopiclone — obtained via prescription or without one from an online pharmacy. [2] He believes that the boundaries between everyday addictions and less socially acceptable ones are becoming increasingly blurred, and also perceives an overlap between them, citing evidence that sugar triggers "the brain's natural opioids," and that the brain can become addicted to them in the same way that it does to morphine or heroin.[3] |

概要 本書は、トンプソンの研究に加え、元アルコール依存症者としての経験と、アルコール依存症匿名会(AA)の12ステップ断酒プログラムへの参加に基づいて いる。[1]: 33–37 彼は依存症の脳疾患説(アルコール依存症の疾患説がその一例)を否定し、依存症はむしろ脳の報酬系、すなわち中脳辺縁系経路に基づく自発的で可逆的な行動 障害だと主張する。トンプソンは、商業目的で技術と社会環境が普遍的に依存症を助長していると主張する。例として、カップケーキなどの糖分豊富な食品によ る砂糖依存症、ポルノ・ビデオゲーム・買い物への依存、アルコールやカフェインといった薬物、コカインやヘロインなどの違法薬物、処方箋あり・なしを問わ ずオンライン薬局から入手されるゾピクロンなどの医療用規制薬物を挙げる。 [2] 彼は、日常的な依存と社会的に受け入れられにくい依存の境界がますます曖昧になりつつあると信じている。また、糖分が「脳の天然オピオイド」を活性化させ る証拠や、脳がモルヒネやヘロインと同様にそれらに依存状態になる可能性を指摘し、両者の間に重なりがあると認識している。[3] |

| Reception The Economist described the book as an "entertaining and informative account" of addiction, although written in a "waspish" style which it considered to understate the seriousness of the issue.[4] ConservativeHome viewed it as an "eye-opening, iconoclastic analysis" of contemporary addiction.[5] In Wired UK, Milo Yiannopoulos felt its perception of a disparity between the evolutionary status quo of human beings and the overwhelming world in which they live was presented with "gentle but terrifyingly persuasive regularity".[6] The book provoked a dispute between Thompson and The Guardian's Tanya Gold, a recovering alcoholic.[7] Gold described it as a "dangerous polemic", accusing Thompson of writing a "poison pen letter" to Alcoholics Anonymous.[8] The Huffington Post's Rupert Wolfe-Murray also criticised Thompson's rejection of the disease model of addiction, suggesting he was giving alcoholism the banality of everyday obsessions and asking if this was a form of denial.[9] Thompson responded to Gold, clarifying his view that addiction is a matter of choice,[10] and also responded to Wolfe-Murray on his blog, writing that the disease model of addiction should not be an "emotional crutch".[11] In The Washington Post, James Norton wrote that Thompson speaks in a deceptively casual voice at first, but ultimately brings the reader through a "whirlwind of anecdotes, interviews and studies", offering an argument with "real force and substance" and engaging reading material.[12] He felt that Thompson's argument isn't likely to be popular, but is a "far more nuanced look at the mechanics of addiction than we lay readers are usually offered".[12] |

評価 エコノミスト誌はこの本を「中毒に関する面白く有益な記述」と評したが、その「辛辣な」文体は問題の深刻さを過小評価していると指摘した。[4] ConservativeHomeは現代の中毒を「目を見開かせるような、既成概念を打ち破る分析」と評価した。[5] ワイアードUK誌のミロ・ヤノプロスは、人類の進化上の現状と圧倒的な現実世界との乖離を「穏やかだが恐ろしいほど説得力のある規則性」で提示していると 評した。[6] 本書はトンプソンとガーディアン紙のタニア・ゴールド(回復期アルコール依存症者)との論争を引き起こした。[7] ゴールドは本書を「危険な論争書」と評し、トンプソンがアルコール依存症匿名会(AA)に「中傷の手紙」を書いたと非難した。[8] ハフィントンポストのルパート・ウルフ=マレーも、トンプソンが依存症の疾病モデルを否定する姿勢を批判。アルコール依存症を日常的な執着の凡庸さとして 扱うのは、一種の否認ではないかと問いただした。[9] トンプソンはゴールドへの反論で、依存症は選択の問題だという自身の見解を明確にした[10]。また自身のブログでウルフ=マレーにも応答し、依存症の疾病モデルは「感情的な支え」であってはならないと記した。[11] ワシントン・ポスト紙のジェームズ・ノートンは、トンプソンは一見気さくな口調で語り始めるが、最終的には読者を「逸話、インタビュー、研究の渦」へと導 き、「真の力と実体」を備えた議論と魅力的な読み物を提供すると書いた。[12] 彼はトンプソンの主張が広く受け入れられる可能性は低いと感じつつも、これは「一般読者に通常提示されるものよりはるかに精緻な中毒のメカニズム分析だ」 と評価した。[12] |

| References 1. Thompson, Damian. (2012) The Fix: How Addiction is Invading our Lives and Taking Over Your World. Collins. ISBN 9780007436088 2. "Solution To Your Medical Problems". Retrieved 12 November 2015. 3. Colantuoni, Carlo; Rada, Pedro et al. 'Evidence that Intermittent, Excessive Sugar Intake Causes Endogenous Opioid Dependence,' Obesity Research 10, 2002. Cited in Thompson (2012), p. 16 4. "Crazy for it". The Economist. 2 June 2012. Retrieved 3 June 2012. 5. "From Gin Lane to porn superhighway". ConservativeHome. 1 June 2012. Retrieved 3 June 2012. 6. Yiannopoulos, Milo (24 May 2012). "The Fix: Damian Thompson explores the murky world of modern addiction". Wired UK. Retrieved 3 June 2012. 7. "Fleet Street's finest former alcoholics war over words". Evening Standard. 31 May 2012. Retrieved 3 June 2012. 8. Gold, Tanya (28 May 2012). "Is addiction a moral defect or a mental illness?". The Guardian. Retrieved 3 June 2012. 9. Wolfe-Murray, Rupert (31 May 2012). "Are We All Addicts?". The Huffington Post. Retrieved 3 June 2012. 10. Thompson, Damian (30 May 2012). "Alcoholics Anonymous saved my life, but not by curing a 'disease'". The Guardian. Retrieved 3 June 2012. 11. Thompson, Damian (1 June 2012). "Do you think alcoholism isn't really a disease? Careful – you'll be branded as a heretic". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on 4 June 2012. Retrieved 3 June 2012. 12. Norton, James (21 May 2013). "'The Fix,' by Damian Thompson". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 25 May 2013. Retrieved 5 June 2013. |

参考文献 1. トンプソン、ダミアン(2012)『フィックス:中毒が私たちの生活を侵食し、世界を支配する仕組み』コリンズ社。ISBN 9780007436088 2. 「医療問題の解決策」。2015年11月12日取得。 3. Colantuoni, Carlo; Rada, Pedro et al. 「間欠的かつ過剰な糖分摂取が内因性オピオイド依存を引き起こす証拠」『Obesity Research』10号、2002年。Thompson (2012) p. 16で引用 4. 「それに夢中」。The Economist。2012年6月2日。2012年6月3日閲覧。 5. 「ジン・レーンからポルノ・スーパーハイウェイへ」. ConservativeHome. 2012年6月1日. 2012年6月3日閲覧。 6. ヤノプロス, ミロ (2012年5月24日). 「フィックス:ダミアン・トンプソンが現代の依存症という不透明な世界を探る」. Wired UK. 2012年6月3日取得。 7. 「フリート・ストリートの元アルコール依存症者たちが言葉で争う」. イブニング・スタンダード. 2012年5月31日. 2012年6月3日取得. 8. ゴールド, ターニャ (2012年5月28日). 「依存症は道徳的欠陥か、精神疾患か」. ガーディアン. 2012年6月3日取得. 9. ウルフ=マレー、ルパート(2012年5月31日)。「我々は皆中毒者か?」。ハフィントンポスト。2012年6月3日取得。 10. トンプソン、ダミアン(2012年5月30日)。「アルコール依存症匿名会が私の命を救った。だがそれは『病気』を治したからではない」。ガーディアン。2012年6月3日閲覧。 11. トンプソン、ダミアン(2012年6月1日)。「アルコール依存症は本当の病気ではないと思うか?注意しろ――異端者扱いされるぞ」。デイリー・テレグラフ。2012年6月4日時点のオリジナルからアーカイブ。2012年6月3日閲覧。 12. ノートン、ジェームズ(2013年5月21日)。「『フィックス』ダミアン・トンプソン著」。ワシントン・ポスト。2013年5月25日にオリジナルからアーカイブ。2013年6月5日に取得。 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Fix_(book) |

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

CC

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆