入門講義「エスノセントリズム」

Short Comments on

Ethnocentrism

入門講義「エスノセントリズム」

Short Comments on

Ethnocentrism

解説:池田光穂

エスノセ ントリズムとは、複 数の民族的「他者」に対して、自己の民族とは異なった存在であり、かつ自 分たちのほうが他者よりも優 越する価値を有するという(集団がもつ)倫理的態度、すなわち価値判断のことを言います。自民族中心主義ともいいます。その英語は ethno-centrism, ethnocentrism, で、ウィリアム・サムナーが『フォークウェイズ』(Sumner, W. G. Folkways. New York: Ginn, 1906)の中で使ったのがその嚆矢(こうし、最初のこと)だと言われています。また、文化を担 うのは民族集団なので、自文化中心主義という表現もエスノセントリズムと同義にみてもいいでしょう(→「ウィリアム・サムナーとエスノセントリズム」「ルードヴィヒ・グンプロヴィッチ」)。

| "Ethnocentrism is

the technical name for this view of things in which one's own group is

the center of everything, and all others are scaled and rated with

reference to it. Folkways correspond to it to cover both the inner and

the outer relation. Each group nourishes its own pride and vanity,

boasts itself superior, exalts its own divinities, and looks with

contempt on outsiders. Each group thinks its own folkways the only

right ones, and if it observes that other groups have other folkways,

these excite its scorn. Opprobrious epithets are derived from these

differences. "Pig-eater," "cow-eater," "uncircumcised," "jabberers,"

are epithets of contempt and abomination. The Tupis called the

Portuguese by a derisive epithet descriptive of birds which have

feathers around their feet, on account of trousers.17 For our present

purpose the most important fact is that ethnocentrism leads a people to

exaggerate and intensify everything in their own folkways which is

peculiar and which differentiates them from others. It therefore

strengthens the folkways." - Sumner, W. G. Folkways.(pp.13-15) |

エスノセントリズムとは、自分のグループがすべての中心であり、他のす

べてのグループはそれを基準にして尺度や評価を決めるという物事の見方の専門的な名称である。民衆的やり方(フォークウェイズ)はこれに対応し、内的関係

と外的関係の両方をカバーする。各集団は自らの誇りと虚栄心を養い、自らの優位性を誇り、自らの神格を称揚し、外部の者を軽蔑する。各集団は自分たちの民

俗を唯一の正しいものと考え、他の集団が他の民俗を持っていることを観察すると、それを軽蔑する。このような違いから、忌み嫌う蔑称が生まれる。「豚食

い」「牛食い」「無割礼」「ぺちゃくちゃ言う連中」などは、軽蔑と嫌悪の蔑称である。(南アメリカ先住民の)トゥピ族は(植民侵略者の)ポルトガル人を、

ズボンのせいで、足の周りに羽がある鳥の蔑称で呼んだ。現在の目的にとって最も重要な事実は、民族中心主義が、民族の民衆の中にある特有で他者と区別する

ものすべてを誇張し強化させるということである。したがって、それは民衆的やり方や思考法を強化する。 |

| Sumner, W. G. Folkways.(pp.13-15) | www.DeepL.com/Translatorに加筆修正した |

エスノセントリズム(自民族中心主義)とは、なんらかの意図的に採用する政治的心情でもありませ んし、また、倫理的態度と言っても心理学が言うエゴセントリック(自己中心的態度)のことでもありません。倫理的態度といっても個人がもつ性向のようなものではなく、手段がもつ、他者の集団に対する優越感情を、説明する論理 のことを、エスノセントリズム(自民族中心主義)と言います。

ここでの民族的他者は、それぞれおなじ文化を共有しているという前提で話されることがあるので、 ethno(=民族の)centrism(=中心からの視座)である自民族中心主義はしばしば「自文化中心主義(じ-ぶんか-ちゅうしん-しゅぎ)」と呼 ばれ ることもあります。

自民族中心主義が、ナショ ナリズムや人種主義の中に組み込まれると、自国民中心主義となり外国人嫌悪や排斥 (xenophobia, ゼノフォビア)や、人種 差別思想につながり、特定の外国人や人種を排斥することが、自分たちのアイデンティティの よりどころとなるという暴力礼讃の生むことはよく知られています。

しかしながら、おしなべて我々はし ばしば自民族中心主義的な態度をとることが多く、とりわけ、他者の集団に対して恐怖を我々が つよく感じる時代には、集団的特性として極端なエスノセントリズム(自民族中心主義)に陥り がちです。その場合、自民族中心主義的な態度が問題なのではなく、排外主義的な態度をとっ て、相手の集団のことを極端に邪悪なものとして一般化したりすることが問題なのです(→「愛 国主義」)。

| Ethnocentrism

in social science and anthropology—as well as in colloquial English

discourse—means to apply one's own culture or ethnicity as a frame of

reference to judge other cultures, practices, behaviors, beliefs, and

people, instead of using the standards of the particular culture

involved. Since this judgment is often negative, some people also use

the term to refer to the belief that one's culture is superior to, or

more correct or normal than, all others—especially regarding the

distinctions that define each ethnicity's cultural identity, such as

language, behavior, customs, and religion.[1] In common usage, it can

also simply mean any culturally biased judgment.[2] For example,

ethnocentrism can be seen in the common portrayals of the Global South

and the Global North. Ethnocentrism is sometimes related to racism, stereotyping, discrimination, or xenophobia. However, the term "ethnocentrism" does not necessarily involve a negative view of the others' race or indicate a negative connotation.[3] The opposite of ethnocentrism is cultural relativism, a guiding philosophy stating that the best way to understand a different culture is through their perspective rather than judging them from the subjective viewpoints shaped by one's own cultural standards. The term "ethnocentrism" was first applied in the social sciences by American sociologist William G. Sumner.[4] In his 1906 book, Folkways, Sumner describes ethnocentrism as "the technical name for the view of things in which one's own group is the center of everything, and all others are scaled and rated with reference to it." He further characterized ethnocentrism as often leading to pride, vanity, the belief in one's own group's superiority, and contempt for outsiders.[5] Over time, ethnocentrism developed alongside the progression of social understandings by people such as social theorist Theodore W. Adorno. In Adorno's The Authoritarian Personality, he and his colleagues of the Frankfurt School established a broader definition of the term as a result of "in group-out group differentiation", stating that ethnocentrism "combines a positive attitude toward one's own ethnic/cultural group (the in-group) with a negative attitude toward the other ethnic/cultural group (the out-group)." Both of these juxtaposing attitudes are also a result of a process known as social identification and social counter-identification.[6] |

社会科学や人類学におけるエスノセントリズムとは、口語的な英語の言説

においても同様だが、他の文化や習慣、行動、信念、人々を判断する際に、その文化に関わる特定の基準を用いるのではなく、自分の文化や民族性を参照枠とし

て適用することを意味する。この判断は否定的であることが多いため、自分の文化が他のすべての文化よりも優れている、あるいはより正しい、あるいは正常で

あるという信念を指す言葉としても使われる。 エスノセントリズムは人種主義、ステレオタイプ、差別、外国人嫌悪と関連することもある。しかし、「エスノセントリズム」という用語は、必ずしも他者の人 種を否定的に見たり、否定的な意味合いを示したりするものではない。エスノセントリズムの反対語は文化相対主義であり、異なる文化を理解する最善の方法 は、自分自身の文化的基準によって形成された主観的視点から判断するのではなく、彼らの視点を通して理解することであるとする指導的哲学である。 エスノセントリズム」という用語は、アメリカの社会学者ウィリアム・G・サムナーによって社会科学に初めて適用された[4]。1906年に出版された著書 『Folkways』の中で、サムナーはエスノセントリズムを「自分の集団がすべての中心であり、他のすべての集団はそれを基準として尺度づけされ、評価 されるという物事の見方の専門的名称」と説明している。彼はさらに、エスノセントリズムはしばしばプライド、虚栄心、自分のグループの優位性の信念、部外 者への侮蔑につながると特徴づけている[5]。 時が経つにつれて、エスノセントリズムは社会理論家テオドール・W・アドルノなどによる社会的理解の進展とともに発展していった。アドルノとフランクフル ト学派の同僚たちは、『権威主義的パーソナリティ』の中で、エスノセントリズムは「自分の民族的/文化的集団(内集団)に対する肯定的な態度と、他の民族 的/文化的集団(外集団)に対する否定的な態度とを結びつけるものである」と述べ、「内集団と外集団の分化」の結果として、この用語のより広範な定義を確 立した。これらの並存する態度の両方は、社会的同一化と社会的反同一化として知られるプロセスの結果でもある[6]。 |

Polish

sociologist Ludwig Gumplowicz is believed to have coined the term

"ethnocentrism" in the 19th century, although he may have merely

popularized it Polish

sociologist Ludwig Gumplowicz is believed to have coined the term

"ethnocentrism" in the 19th century, although he may have merely

popularized it |

ポーランドの社会学者ルードヴィヒ・グンプロ

ヴィッチは、19世紀に「エスノセントリズム」という言葉を作ったと考えられているが、単にそれを広めただけかもしれない。 ポーランドの社会学者ルードヴィヒ・グンプロ

ヴィッチは、19世紀に「エスノセントリズム」という言葉を作ったと考えられているが、単にそれを広めただけかもしれない。 |

| Origins and development The term ethnocentrism derives from two Greek words: "ethnos", meaning nation, and "kentron", meaning center. Scholars believe this term was coined by Polish sociologist Ludwig Gumplowicz in the 19th century, although alternate theories suggest that he only popularized the concept as opposed to inventing it.[7][8] He saw ethnocentrism as a phenomenon similar to the delusions of geocentrism and anthropocentrism, defining Ethnocentrism as "the reasons by virtue of which each group of people believed it had always occupied the highest point, not only among contemporaneous peoples and nations, but also in relation to all peoples of the historical past."[7] Subsequently, in the 20th century, American social scientist William G. Sumner proposed two different definitions in his 1906 book Folkways. Sumner stated that "Ethnocentrism is the technical name for this view of things in which one's own group is the center of everything, and all others are scaled and rated with reference to it."[9] In the War and Other Essays (1911), he wrote that "the sentiment of cohesion, internal comradeship, and devotion to the in-group, which carries with it a sense of superiority to any out-group and readiness to defend the interests of the in-group against the out-group, is technically known as ethnocentrism."[10] According to Boris Bizumic, it is a popular misunderstanding that Sumner originated the term ethnocentrism, stating that in actuality, he brought ethnocentrism into the mainstreams of anthropology, social science, and psychology through his English publications.[8] Several theories have been reinforced through the social and psychological understandings of ethnocentrism including T.W Adorno's Authoritarian Personality Theory (1950), Donald T. Campbell's Realistic Group Conflict Theory (1972), and Henri Tajfel's Social identity theory (1986). These theories have helped to distinguish ethnocentrism as a means to better understand the behaviors caused by in-group and out-group differentiation throughout history and society.[8] |

起源と発展 エスノセントリズムという言葉は、ギリシャ語の2つの言葉に由来する: 国民を意味する 「ethnos 」と中心を意味する 「kentron 」である。学者たちは、この用語は19世紀にポーランドの社会学者ルートヴィヒ・グンプロヴィッチによって作られたと考えているが、別の説によれば、彼は この概念を発明したのではなく、普及させたに過ぎないとされている。 [彼はエスノセントリズムを地動説や人間中心主義の妄想に似た現象とみなし、エスノセントリズムを「それぞれの集団が、同時代の民族や国民の間だけでな く、歴史的過去のすべての民族との関係においても、常に最高の位置を占めていると信じている理由」と定義した[7]。 その後、20世紀になって、アメリカの社会科学者ウィリアム・G・サムナーは1906年の著書『フォークウェイズ』の中で2つの異なる定義を提唱した。サ ムナーは、「エスノセントリズムとは、自分自身の集団がすべての中心であり、他のすべての集団はそれを基準として尺度づけられ、評価されるという、このよ うなものの見方の専門的な名称である」と述べている。 「ボリス・ビズミックによれば、サムナーがエスノセントリズムという用語を生み出したというのは一般的な誤解であり、実際にはサムナーは英語の出版物を通 じてエスノセントリズムを人類学、社会科学、心理学の主流に持ち込んだと述べている[8]。 T.W.アドルノの権威主義的パーソナリティ理論(1950年)、ドナルド・T.キャンベルの現実的集団対立理論(1972年)、ヘンリ・ターイフェルの 社会的アイデンティティ理論(1986年)など、いくつかの理論がエスノセントリズムの社会的・心理学的理解を通じて強化されてきた。これらの理論は、歴 史と社会を通して内集団と外集団の分化によって引き起こされる行動をよりよく理解する手段として、エスノセントリズムを区別するのに役立っている[8]。 |

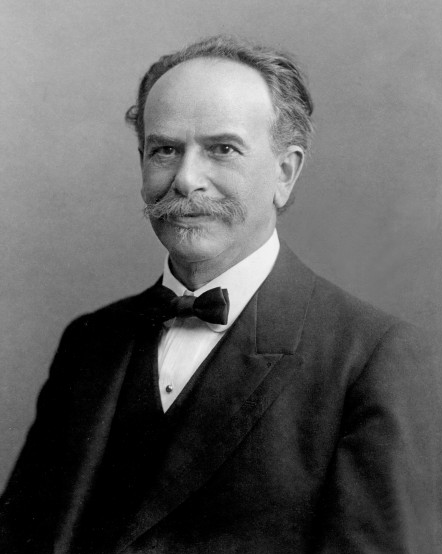

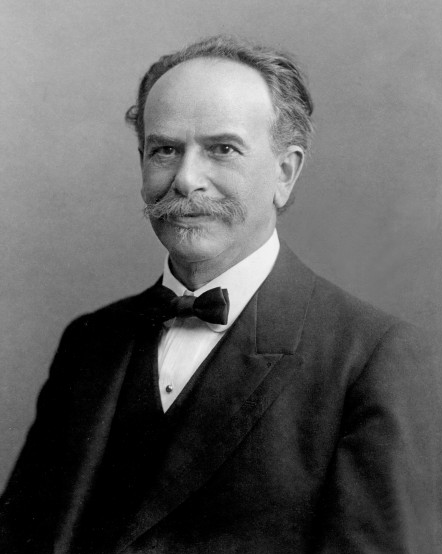

Ethnocentrism in social sciences William Graham Sumner In social sciences, ethnocentrism means to judge another culture based on the standard of one's own culture instead of the standard of the other particular culture.[11] When people use their own culture as a parameter to measure other cultures, they often tend to think that their culture is superior and see other cultures as inferior and bizarre. Ethnocentrism can be explained at different levels of analysis. For example, at an intergroup level, this term is seen as a consequence of a conflict between groups; while at the individual level, in-group cohesion and out-group hostility can explain personality traits.[12] Also, ethnocentrism can helps us to explain the construction of identity. Ethnocentrism can explain the basis of one's identity by excluding the outgroup that is the target of ethnocentric sentiments and used as a way of distinguishing oneself from other groups that can be more or less tolerant.[13] This practice in social interactions creates social boundaries, such boundaries define and draw symbolic boundaries of the group that one wants to be associated with or belong to.[13] In this way, ethnocentrism is a term not only limited to anthropology but also can be applied to other fields of social sciences like sociology or psychology. Ethnocentrism may be particularly enhanced in the presence of interethnic competition, hostility and violence.[14] On the other hand, ethnocentrism may negatively influence expatriate worker's performance.[15] A more recent interpretation of ethnocentrism, which expands upon the work of Claude Lévi-Strauss, highlights its positive dimension. Political sociologist Audrey Alejandro of the London School of Economics argues that, while ethnocentrism does produce social hierarchies, it also produces diversity by maintaining the different dispositions, practices, and knowledge of identity groups. Diversity is both fostered and undermined by ethnocentrism. Ethnocentrism, for Alejandro, is therefore neither something to be suppressed nor celebrated uncritically. Rather, observers can cultivate a 'balanced ethnocentrism', (individual self worth) allowing themselves to be challenged and transformed by difference whilst still protecting difference.[16] |

社会科学におけるエスノセントリズム ウィリアム・グラハム・サムナー 社会科学におけるエスノセントリズムとは、他の特定の文化の基準ではなく、自分の文化の基準に基づいて他の文化を判断することを意味する[11]。人々が 他の文化を測定するためのパラメータとして自分の文化を使用する場合、多くの場合、彼らは自分の文化が優れていると考え、他の文化は劣っており、奇妙であ ると見なす傾向がある。エスノセントリズムはさまざまな分析レベルで説明することができる。例えば、集団間レベルでは、この用語は集団間の対立の結果とみ なされる。一方、個人レベルでは、内集団の結束と外集団の敵意は性格特性を説明することができる。エスノセントリズムは、エスノセントリックな感情の対象 である外集団を排除し、多かれ少なかれ寛容である可能性のある他の集団から自らを区別する方法として使用されることで、自分のアイデンティティの基礎を説 明することができる[13]。社会的相互作用におけるこのような実践は社会的境界を作り出し、そのような境界は、自分が関連づけられたい、あるいは所属し たい集団の象徴的境界を定義し、描く。エスノセントリズムは、民族間の競争、敵意、暴力が存在する場合に特に高まる可能性がある[14]。一方、エスノセ ントリズムは海外駐在員のパフォーマンスにマイナスの影響を与える可能性がある[15]。 クロード・レヴィ=ストロースの研究を発展させた、より最近のエスノセントリズムの解釈は、その肯定的な側面を強調している。ロンドン・スクール・オブ・ エコノミクスの政治社会学者オードリー・アレハンドロは、エスノセントリズムは社会階層を生み出すが、アイデンティティ集団の異なる気質、実践、知識を維 持することによって多様性も生み出すと論じている。多様性はエスノセントリズムによって育まれ、また損なわれるのである。したがって、アレハンドロにとっ てのエスノセントリズムは、抑制されるべきものでも、無批判に称賛されるべきものでもない。むしろ、観察者は「バランスの取れたエスノセントリズム」(個 人の自己価値)を培うことができ、差異を守りつつも、差異によって挑戦され、変容することができるのである[16]。 |

| Anthropology The classifications of ethnocentrism originate from the studies of anthropology. With its omnipresence throughout history, ethnocentrism has always been a factor in how different cultures and groups related to one another.[17] Examples including how historically, foreigners would be characterized as "Barbarians". These trends exist in complex societies, e.g., "the Jews consider themselves to be the 'chosen people', and the Greeks defend all foreigners as 'barbarians'", and how China believed their country to be "the centre of the world".[17] However, the anthropocentric interpretations initially took place most notably in the 19th century when anthropologists began to describe and rank various cultures according to the degree to which they had developed significant milestones, such as monotheistic religions, technological advancements, and other historical progressions. Most rankings were strongly influenced by colonization and the belief to improve societies they colonized, ranking the cultures based on the progression of their western societies and what they classified as milestones. Comparisons were mostly based on what the colonists believed as superior and what their western societies have accomplished. Victorian era politician and historian Thomas Macaulay once claimed that "one shelf of a Western library" had more knowledge than the centuries of text and literature written by Asian cultures.[18] Ideas developed by Western scientists such as Herbert Spencer, including the concept of the "survival of the fittest", contained ethnocentric ideals; influencing the belief that societies which were 'superior' were most likely to survive and prosper.[18] Edward Said's concept of Orientalism represented how Western reactions to non-Western societies were based on an "unequal power relationship" that the Western world developed due to its history of colonialism and the influence it held over non-Western societies.[18][19] The ethnocentric classification of "primitive" were also used by 19th and 20th century anthropologists and represented how unawareness in cultural and religious understanding changed overall reactions to non-Western societies. 19th-century anthropologist Edward Burnett Tylor wrote about "primitive" societies in Primitive Culture (1871), creating a "civilization" scale where it was implied that ethnic cultures preceded civilized societies.[20] The use of "savage" as a classification is modernly known as "tribal" or "pre-literate" where it was usually referred as a derogatory term as the "civilization" scale became more common.[20] Examples that demonstrate a lack of understanding include when European travelers judged different languages based on the fact that they could not understand it and displayed a negative reaction, or the intolerance displayed by Westerners when exposed to unknown religions and symbolisms.[20] Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel, a German philosopher, justified Western imperialism by reasoning that since the non-Western societies were "primitive" and "uncivilized", their culture and history was not worth conserving and thus should welcome Westernization.[21]  Photograph of anthropologist Franz Boas Franz Boas Anthropologist Franz Boas saw the flaws in this formulaic approach to ranking and interpreting cultural development and committed himself to overthrowing this inaccurate reasoning due to many factors involving their individual characteristics. With his methodological innovations, Boas sought to show the error of the proposition that race determined cultural capacity.[22] In his 1911 book The Mind of Primitive Man, Boas wrote that:[23] It is somewhat difficult for us to recognize that the value which we attribute to our own civilization is due to the fact that we participate in this civilization, and that it has been controlling all our actions from the time of our birth; but it is certainly conceivable that there may be other civilizations, based perhaps on different traditions and on a different equilibrium of emotion and reason, which are of no less value than ours, although it may be impossible for us to appreciate their values without having grown up under their influence. Together, Boas and his colleagues propagated the certainty that there are no inferior races or cultures. This egalitarian approach introduced the concept of cultural relativism to anthropology, a methodological principle for investigating and comparing societies in as unprejudiced a way as possible and without using a developmental scale as anthropologists at the time were implementing.[22] Boas and anthropologist Bronisław Malinowski argued that any human science had to transcend the ethnocentric views that could blind any scientist's ultimate conclusions.[citation needed] Both had also urged anthropologists to conduct ethnographic fieldwork to overcome their ethnocentrism. To help, Malinowski would develop the theory of functionalism as guides for producing non-ethnocentric studies of different cultures. Classic examples of anti-ethnocentric anthropology include Margaret Mead's Coming of Age in Samoa (1928), which in time has met with severe criticism for its incorrect data and generalisations, Malinowski's The Sexual Life of Savages in North-Western Melanesia (1929), and Ruth Benedict's Patterns of Culture (1934). Mead and Benedict were two of Boas's students.[22] Scholars generally agree that Boas developed his ideas under the influence of the German philosopher Immanuel Kant. Legend has it that, on a field trip to the Baffin Islands in 1883, Boas would pass the frigid nights reading Kant's Critique of Pure Reason. In that work, Kant argued that human understanding could not be described according to the laws that applied to the operations of nature, and that its operations were therefore free, not determined, and that ideas regulated human action, sometimes independent of material interests. Following Kant, Boas pointed out the starving Eskimos who, because of their religious beliefs, would not hunt seals to feed themselves, thus showing that no pragmatic or material calculus determined their values.[23][24] |

人類学 エスノセントリズムの分類は、人類学の研究に由来する。歴史を通じて遍在するエスノセントリズムは、異なる文化や集団が互いにどのように関係しあうかとい う点において、常に要因となってきた。このような傾向は複雑な社会にも存在し、例えば「ユダヤ人は自分たちを『選ばれし民』であると考え、ギリシャ人はす べての外国人を『野蛮人』であると擁護する」、また中国は自分たちの国を「世界の中心」であると信じていた[17]。しかし、人間中心主義的な解釈が最初 に行われたのは、人類学者が一神教の宗教、技術の進歩、その他の歴史的進歩など、重要なマイルストーンを発展させた度合いに応じて様々な文化を記述し、ラ ンク付けし始めた19世紀が最も顕著である。 ほとんどのランキングは、植民地化と、植民地化した社会を向上させるという信念に強く影響され、西洋社会の進歩や、マイルストーンとして分類したものに基 づいて、文化をランク付けした。比較のほとんどは、植民地主義者が優れていると信じていたものや、西洋社会が成し遂げたことに基づいていた。ヴィクトリア 朝時代の政治家であり歴史家でもあったトーマス・マコーレーは、「西洋の図書館の1つの棚」には、アジア文化によって書かれた何世紀もの文章や文学よりも 多くの知識があると主張したことがある[18]。適者生存」の概念を含む、ハーバート・スペンサーなどの西洋の科学者によって開発された考え方には、民族 中心主義的な理想が含まれていた。 [18] エドワード・サイードのオリエンタリズムの概念は、非西洋社会に対する西洋の反応が、西洋世界がその植民地主義の歴史と非西洋社会に対する影響力のために 発展させた「不平等な力関係」にいかに基づいているかを表していた[18][19]。 原始人」というエスノセントリックな分類は19世紀と20世紀の人類学者によっても用いられ、文化的・宗教的理解における無自覚さが非西洋社会に対する全 体的な反応をどのように変化させたかを表していた。19世紀の人類学者エドワード・バーネット・タイラー(Edward Burnett Tylor)は『原始文化(Primitive Culture)』(1871年)の中で「原始的」な社会について書いており、「文明」の尺度を作り出し、そこでは民族文化が文明社会に先行することが暗 示されていた[20]。 [20]理解不足を示す例としては、ヨーロッパの旅行者が異なる言語を理解できないという事実に基づいて判断し、否定的な反応を示したり、西洋人が未知の 宗教や象徴に触れたときに示した不寛容さなどがある[20]。ドイツの哲学者であるゲオルク・ヴィルヘルム・フリードリヒ・ヘーゲルは、非西洋社会は「原 始的」で「未開」であるため、彼らの文化や歴史は保存する価値がなく、したがって西洋化を歓迎すべきであると推論して西洋帝国主義を正当化した[21]。  人類学者フランツ・ボアズの写真 フランツ・ボアズ 人類学者フランツ・ボアズは、文化的発達をランク付けし解釈するこの定型的なアプローチの欠陥を見抜き、個人の特性に関わる多くの要因によるこの不正確な 推論を覆すことに尽力した。ボアズはその方法論の革新によって、人種が文化的能力を決定するという命題の誤りを示そうとした[22]。1911年の著書 『原始人の心』の中で、ボアズは次のように書いている[23]。 しかし、おそらく異なる伝統に基づき、感情と理性の異なる均衡に基づき、われわれに劣らない価値を持つ文明が他にも存在することは確かに考えられる。 ボアズと彼の同僚たちはともに、劣った人種や文化は存在しないという確信を広めた。この平等主義的なアプローチは、文化相対主義という概念を人類学に導入 し、当時の人類学者が実践していたような発展尺度を用いずに、できるだけ偏見のない方法で社会を調査し比較するための方法論的原則となった[22]。ボア ズと人類学者のブロニスワフ・マリノフスキーは、あらゆる人間科学は、科学者の最終的な結論を盲目にしかねない民族中心主義的な見解を超越しなければなら ないと主張した[要出典]。 また、両者とも人類学者に対して、民族中心主義を克服するために民族誌的なフィールドワークを行うよう促していた。その一助として、マリノフスキーは異な る文化について非民族中心主義的な研究を行うための指針として機能主義の理論を発展させることになる。反民族中心主義的人類学の古典的な例としては、マー ガレット・ミードの『サモアの青春』(1928年)、マリノフスキーの『北西メラネシアにおける未開人の性生活』(1929年)、ルース・ベネディクトの 『文化のパターン』(1934年)などがある。ミードとベネディクトはボアズの2人の弟子であった[22]。 ボアズがドイツの哲学者イマヌエル・カントの影響を受けて彼の思想を発展させたという点については、学者たちも概ね同意している。伝説によると、1883 年にバフィン諸島をフィールドトリップしたボアズは、極寒の夜をカントの『純粋理性批判』を読んで過ごしたという。その著作の中でカントは、人間の理解は 自然の営みに適用される法則に従って記述することはできず、したがってその営みは決定されたものではなく自由であり、観念が人間の行動を規制し、時には物 質的利害とは無関係であると主張した。カントに従って、ボアズは飢餓に苦しむエスキモーを指摘した。彼らは宗教的信念のために、自分たちを養うためにアザ ラシを狩ることはせず、その結果、実利的あるいは物質的な計算が彼らの価値観を決定することはないことを示した[23][24]。 |

| Causes Ethnocentrism is believed to be a learned behavior embedded into a variety of beliefs and values of an individual or group.[17] Due to enculturation, individuals in in-groups have a deeper sense of loyalty and are more likely to follow the norms and develop relationships with associated members.[4] Within relation to enculturation, ethnocentrism is said to be a transgenerational problem since stereotypes and similar perspectives can be enforced and encouraged as time progresses.[4][1] Although loyalty can increase better in-grouper approval, limited interactions with other cultures can prevent individuals to have an understanding and appreciation towards cultural differences resulting in greater ethnocentrism.[4] The social identity approach suggests that ethnocentric beliefs are caused by a strong identification with one's own culture that directly creates a positive view of that culture. It is theorized by Henri Tajfel and John C. Turner that to maintain that positive view, people make social comparisons that cast competing cultural groups in an unfavorable light.[25] Alternative or opposite perspectives could cause individuals to develop naïve realism and be subject to limitations in understandings.[26] These characteristics can also lead to individuals to become subject to ethnocentrism, when referencing out-groups, and black sheep effect, where personal perspectives contradict those from fellow in-groupers.[26] Realistic conflict theory assumes that ethnocentrism happens due to "real or perceived conflict" between groups. This also happens when a dominant group may perceive the new members as a threat.[3] Scholars have recently demonstrated that individuals are more likely to develop in-group identification and out-group negatively in response to intergroup competition, conflict, or threat.[4] Although the causes of ethnocentric beliefs and actions can have varying roots of context and reason, the effects of ethnocentrism has had both negative and positive effects throughout history. The most detrimental effects of ethnocentrism resulting into genocide, apartheid, slavery, and many violent conflicts. Historical examples of these negative effects of ethnocentrism are The Holocaust, the Crusades, the Trail of Tears, and the internment of Japanese Americans. These events were a result of cultural differences reinforced inhumanely by a majority group who thought of themselves as superior. In his 1976 book on evolution, The Selfish Gene, evolutionary biologist Richard Dawkins writes that "blood-feuds and inter-clan warfare are easily interpretative in terms of Hamilton's genetic theory."[27] Simulation-based experiments in evolutionary game theory have attempted to provide an explanation for the selection of ethnocentric-strategy phenotypes.[28][29] The positive examples of ethnocentrism throughout history have aimed to prohibit the callousness of ethnocentrism and reverse the perspectives of living in a single culture. These organizations can include the formation of the United Nations; aimed to maintain international relations, and the Olympic Games; a celebration of sports and friendly competition between cultures.[17] |

原因 エスノセントリズムは、個人や集団の様々な信念や価値観に組み込まれた学習行動であると考えられている[17]。 文化化により、集団内の個人はより深い忠誠心を持ち、規範に従い、関連するメンバーとの関係を発展させる傾向がある[4]。文化化に関連して、エスノセン トリズムは世代を超えた問題であると言われている。 社会的同一性アプローチは、自文化に対する強い同一性が、その文化に対する肯定的な見方を直接生み出すことによって、自国中心主義的信念が引き起こされる ことを示唆している。ヘンリ・タージフェルとジョン・C・ターナーによって、その肯定的な見方を維持するために、人々は競合する文化集団を不利な光で投げ かけるような社会的比較を行うと理論化されている[25]。 このような特性はまた、外集団に言及する際にエスノセントリズムに陥ったり、個人的な視点が内集団の仲間の視点と矛盾するブラックシープ効果に陥ったりす る可能性がある[26]。 現実的葛藤理論では、エスノセントリズムは集団間の「現実または知覚された葛藤」によって起こると仮定している。これはまた、支配的な集団が新しいメン バーを脅威と認識する場合にも起こる。 エスノセントリックな信念や行動の原因には様々な背景や理由が根底にある可能性があるが、エスノセントリズムの影響は歴史を通じて否定的な影響も肯定的な 影響も及ぼしてきた。エスノセントリズムの最も有害な影響は、大量虐殺、アパルトヘイト、奴隷制度、そして多くの暴力的な紛争へと発展した。エスノセント リズムの悪影響の歴史的な例としては、ホロコースト、十字軍、涙の道、日系アメリカ人の強制収容などがある。これらの出来事は、自分たちが優れていると考 える多数派グループによって、文化の違いが非人道的に強化された結果である。進化生物学者であるリチャード・ドーキンスは、1976年に出版した進化論に 関する著書『利己的な遺伝子』の中で、「血の争いや氏族間の戦争は、ハミルトンの遺伝理論の観点から容易に解釈することができる」と書いている[27]。 進化ゲーム理論におけるシミュレーションに基づく実験では、民族中心主義的戦略の表現型が選択されることの説明が試みられている[28][29]。 歴史上、エスノセントリズムの肯定的な例は、エスノセントリズムの無慈悲さを禁止し、単一文化に生きる視点を逆転させることを目的としてきた。このような 組織には、国際関係を維持することを目的とした国連の形成や、スポーツの祭典であり文化間の切磋琢磨を目的としたオリンピックが含まれる[17]。 |

| Effects A study in New Zealand was used to compare how individuals associate with in-groups and out-groupers and has a connotation to discrimination.[30] Strong in-group favoritism benefits the dominant groups and is different from out-group hostility and/or punishment.[30] A suggested solution is to limit the perceived threat from the out-group that also decreases the likeliness for those supporting the in-groups to negatively react.[30] Ethnocentrism also influences consumer preference over which goods they purchase. A study that used several in-group and out-group orientations have shown a correlation between national identity, consumer cosmopolitanism, consumer ethnocentrism, and the methods consumers choose their products, whether imported or domestic.[31] Countries with high levels of nationalism and isolationism are more likely to demonstrate consumer ethnocentrism, and have a significant preference for domestically-produced goods.[32] |

効果 ニュージーランドでの研究は、個人が内集団と外集団のどちらとどのように付き合うかを比較するために使用され、差別の意味合いを持っている[30]。強い 内集団の好意主義は支配的な集団に利益をもたらし、外集団の敵意や罰とは異なる[30]。提案された解決策は、外集団からの脅威の認知を制限することであ り、それはまた、内集団を支持する人々が否定的に反応する可能性を減少させる[30]。 エスノセントリズムは、消費者がどの商品を購入するかという選好にも影響を及ぼす。いくつかの内集団志向と外集団志向を用いた研究では、国民アイデンティ ティ、消費者コスモポリタニズム、消費者エスノセントリズム、消費者が輸入品か国産品かを問わず製品を選択する方法の間に相関関係があることが示されてい る[31]。ナショナリズムと孤立主義のレベルが高い国ほど、消費者エスノセントリズムを示す可能性が高く、国産品を好む傾向が顕著である[32]。 |

| Ethnocentrism and racism Ethnocentrism is usually associated with racism. However, as mentioned before, ethnocentrism does not necessarily implicate a negative connotation. In European research, the term racism is not linked to ethnocentrism because Europeans avoid applying the concept of race to humans; meanwhile, using this term is not a problem for American researchers.[3] Since ethnocentrism implicated a strong identification with one's in-group, it mostly automatically leads to negative feelings and stereotyping to the members of the outgroup, which can be confused with racism.[3] Finally, scholars agree that avoiding stereotypes is an indispensable prerequisite to overcome ethnocentrism; and mass media play a key role regarding this issue. The differences that each culture possess causes could hinder one another leading to ethnocentrism and racism. A Canadian study established the differences among French Canadian and English Canadian respondents based on products that would be purchased due to ethnocentrism and racism.[33] Due to how diverse the world has become, society has begun to misinterpret the term cultural diversity, by using ethnocentrism to create controversy among all cultures. |

エスノセントリズムと人種主義 エスノセントリズムは通常、人種主義と結びついている。しかし、前述したように、エスノセントリズムは必ずしも否定的な意味合いを含んでいるわけではな い。ヨーロッパの研究では人種主義とエスノセントリズムは結びつかないが、それはヨーロッパ人が人種という概念を人間に当てはめることを避けているからで ある。 [3] 民族中心主義(エスノセントリズム)は自己の内集団との強い同一化を意味するため、ほとんどの場合、自動的に外集団のメンバーに対する否定的感情やステレ オタイプにつながり、人種差別と混同される可能性がある[3] 。それぞれの文化が持つ違いが、民族中心主義や人種主義につながる互いの妨げになる可能性がある。カナダの研究では、フランス系カナダ人とイギリス系カナ ダ人の回答者の間で、エスノセントリズムと人種差別のために購入する商品の違いが確認された[33]。世界がいかに多様になったかによって、社会は文化的 多様性という言葉を誤解し始め、エスノセントリズムを使ってあらゆる文化の間で論争を巻き起こしている。 |

| Effects of ethnocentrism in the

media Film As the United States leads the film industry in worldwide revenue, ethnocentric views can be transmitted through character tropes and underlying themes.[34] The 2003 film "The Last Samurai," was analyzed to have strong ethnocentric themes, such as in-group preference and the tendency to show judgement towards those in the out-group.[35] Similarly, the film received criticism for historical inaccuracies and perpetuating a "white savior narrative," showing a tendency for ethnocentrism centered around the United States.[36] Social media Approximately 67.1% of the global population use the internet regularly, with 63.7% of the population being social media users.[37][38] In a 2023 study, researchers found that social media can enable its users to become more tolerant of other people, bridging the gap between cultures, and contributing to global knowledge.[39] In a similar study done regarding social media use by Kenyan teens, researchers found that when social media is limited to a certain group, it can increase ethnocentric views and ideologies.[40] |

メディアにおけるエスノセントリズムの影響 映画 2003年の映画『ラストサムライ』には、内集団への好意や外集団の人々への判断の傾向など、強いエスノセントリックなテーマがあると分析されている [35]。同様に、この映画は歴史的に不正確であり、「白人の救世主物語」を永続させているという批判を受け、アメリカを中心としたエスノセントリズムの 傾向を示している[36]。 ソーシャルメディア 世界人口の約67.1%が定期的にインターネットを利用しており、人口の63.7%がソーシャルメディアユーザーである[37][38]。2023年の研 究では、研究者は、ソーシャルメディアによって、ユーザーが他者に対してより寛容になり、文化間のギャップを埋め、グローバルな知識に貢献できることを発 見した[39]。ケニアの10代の若者のソーシャルメディア利用に関して行われた同様の研究では、研究者は、ソーシャルメディアが特定のグループに限定さ れると、エスノセントリックな見方やイデオロギーを増加させる可能性があることを発見した[40]。 |

| Afrocentrism American exceptionalism Americentrism Asiocentrism Chosen people Collective narcissism Consumer ethnocentrism Ethnic nationalism Eurocentrism Hellenocentrism Indocentrism Mediterraneanism Mortality salience Nordicism Sinocentrism Little China Xenocentrism Zionism |

アフリカ中心主義 アメリカ例外主義 アメリカ中心主義 アジア中心主義 選ばれた人々 集団的ナルシシズム 消費者エスノセントリズム 民族ナショナリズム ヨーロッパ中心主義 ヘレノセントリズム インド中心主義 地中海主義 死生観 北欧中心主義 中国中心主義 リトル・チャイナ ゼノセントリズム シオニズム |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ethnocentrism |

リンク

文献

その他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

みんなのための喰人 入門; Cannibalism of the People, by the people, for the people

++

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆