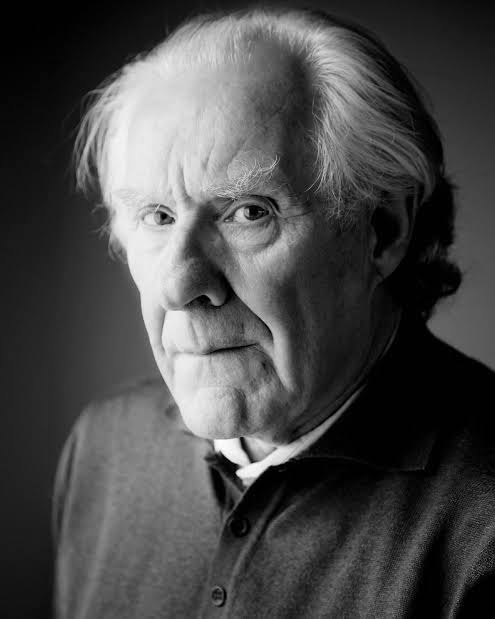

アラン・バディウ

Alain Badiou, b.1937

☆ アラン・バディウ(1937年1月17日生まれ)はフランスの哲学者で、かつてパリ第8大学でジル・ドゥルーズ、ミシェル・フーコー、ジャン=フランソ ワ・リオタールらとともに哲学科を創設した。バディウの仕事は、数学の哲学的応用、特に集合論とカテゴリー論に大きく影響されている。バディウの「存在と出来事」プロジェクトは、存在、真理、出来事、主体の概念について考察するもので、戦後フランス思想の典型とされた言語的相対主義の否定によって定義されている。同業者とは異なり、バディウは普遍主義と真理という考えを公然と信じている。彼の作品は、様々な無関心概念を広く応用していることで注目される。バディウは多くの政治団体に参加し、政治的な出来事について定期的にコメントしている。バディウは政治勢力としての共産主義の復活を主張している。

︎▶イデオロギーとしての倫理︎▶︎︎革命的主体とは誰か?▶︎バイオエシックスと国家が結びつくとナチズムになる▶ニーチェ『善悪の彼岸』ノート︎︎▶︎ジル・ドゥルーズ 2.0▶︎︎イデオロギー的カテゴリーとしての寛容▶︎バイオエシックスの可能性▶︎︎暴君の血まみれのローブ▶︎供犠獣としてのイエス・キリスト▶︎寛容的理性のアンチノミー▶︎「血に混濁した潮が解き放たれ」▶ニコマコス倫理学︎︎▶カルメンのエチカ(倫理学)︎▶︎︎いくたびもミッシェル▶︎統治性▶君は日本人論とどのように付き合うのか?▶︎思弁的リアリズム▶︎︎ルイ・アルチュセール▶︎マーク・フィッシャー▶︎︎

| Alain

Badiou (/bɑːˈdjuː/;[3] French: [alɛ̃ badju] ⓘ; born 17 January 1937) is

a French philosopher, formerly chair of Philosophy at the École normale

supérieure (ENS) and founder of the faculty of Philosophy of the

Université de Paris VIII with Gilles Deleuze, Michel Foucault and

Jean-François Lyotard. Badiou's work is heavily informed by

philosophical applications of mathematics, in particular set theory and

category theory. Badiou's "Being and Event" project considers the

concepts of being, truth, event and the subject defined by a rejection

of linguistic relativism seen as typical of postwar French thought.

Unlike his peers, Badiou openly believes in the idea of universalism

and truth. His work is notable for his widespread applications of

various conceptions of indifference. Badiou has been involved in a

number of political organisations, and regularly comments on political

events. Badiou argues for a return of communism as a political force.[4] |

ア

ラン・バディウ(/bɑÐ,;[3] French: [alɛ badjuÐ] ↪So_24D8;

1937年1月17日生まれ)はフランスの哲学者で、かつてパリ第8大学でジル・ドゥルーズ、ミシェル・フーコー、ジャン=フランソワ・リオタールらとと

もに哲学科を創設した。バディウの仕事は、数学の哲学的応用、特に集合論とカテゴリー論に大きく影響されている。バディウの「存在と出来事」プロジェクト

は、存在、真理、出来事、主体の概念について考察するもので、戦後フランス思想の典型とされた言語的相対主義の否定によって定義されている。同業者とは異

なり、バディウは普遍主義と真理という考えを公然と信じている。彼の作品は、様々な無関心概念を広く応用していることで注目される。バディウは多くの政治

団体に参加し、政治的な出来事について定期的にコメントしている。バディウは政治勢力としての共産主義の復活を主張している[4]。 |

| Biography Badiou is the son of the mathematician Raymond Badiou [fr] (1905–1996), who was a working member of the Resistance in France during World War II. Alain Badiou was a student at the Lycée Louis-Le-Grand and then the École Normale Supérieure (1955–1960).[5] In 1960, he wrote his diplôme d'études supérieures [fr] (roughly equivalent to an MA thesis) on Spinoza for Georges Canguilhem (the topic was "Structures of Demonstration in the First Two Books of Spinoza's Ethics", "Structures démonstratives dans les deux premiers livres de l'Éthique de Spinoza").[6] He taught at the lycée in Reims from 1963 where he became a close friend of fellow playwright (and philosopher) François Regnault,[7] and published two novels before moving first to the faculty of letters of the University of Reims (the collège littéraire universitaire)[8] and then to the University of Paris VIII (Vincennes-Saint Denis) in 1969.[9] Badiou was politically active very early on, and was one of the founding members of the Unified Socialist Party (PSU). The PSU was particularly active in the struggle for the decolonization of Algeria. He wrote his first novel, Almagestes, in 1964. In 1967 he joined a study group organized by Louis Althusser, became increasingly influenced by Jacques Lacan and became a member of the editorial board of Cahiers pour l'Analyse.[9] By then he "already had a solid grounding in mathematics and logic (along with Lacanian theory)",[9] and his own two contributions to the pages of Cahiers "anticipate many of the distinctive concerns of his later philosophy".[9] The student uprisings of May 1968 reinforced Badiou's commitment to the far Left, and he participated in increasingly militant groups, such as the Union des communistes de France marxiste-léniniste [fr] (UCFml). To quote Badiou himself, the UCFml is "the Maoist organization established in late 1969 by Natacha Michel, Sylvain Lazarus, myself and a fair number of young people".[10] During this time, Badiou joined the faculty of the newly founded University of Paris VIII (Vincennes-Saint Denis) which was a bastion of counter-cultural thought. There he engaged in fierce intellectual debates with fellow professors Gilles Deleuze and Jean-François Lyotard, whose philosophical works he considered unhealthy deviations from the Althusserian program of a scientific Marxism. In the 1980s, as both Althusserian structural Marxism and Lacanian psychoanalysis went into decline (after Lacan died and Althusser was committed to a psychiatric hospital), Badiou published more technical and abstract philosophical works, such as Théorie du sujet (1982), and his magnum opus, Being and Event (1988). Nonetheless, Badiou has never renounced Althusser or Lacan, and sympathetic references to Marxism and psychoanalysis are not uncommon in his more recent works (most notably Petit panthéon portatif / Pocket Pantheon).[11][12] He took up his current position at the ENS in 1999. He is also associated with a number of other institutions, such as the Collège International de Philosophie. He was a member of L'Organisation Politique [fr] which, as mentioned above, he founded in 1985 with some comrades from the Maoist UCFml. This organization disbanded in 2007, according to the French Wikipedia article (linked to in the previous sentence). In 2002, he was a co-founder of the Centre International d'Etude de la Philosophie Française Contemporaine, alongside Yves Duroux and his former student Quentin Meillassoux.[13] Badiou has also enjoyed success as a dramatist with plays such as Ahmed le Subtil. In the last decade, an increasing number of Badiou's works have been translated into English, such as Ethics, Deleuze, Manifesto for Philosophy, Metapolitics, and Being and Event. Short pieces by Badiou have likewise appeared in American and English periodicals, such as Lacanian Ink, New Left Review, Radical Philosophy, Cosmos and History and Parrhesia. Unusually for a contemporary European philosopher his work is increasingly being taken up by militants in countries like India, the Democratic Republic of Congo and South Africa.[citation needed] In 2014–15, Badiou had the role of Honorary President at The Global Center for Advanced Studies.[14] |

略歴 数学者レイモン・バディウ[fr](1905-1996)の息子で、第二次世界大戦中、フランスのレジスタンス活動をしていた。アラン・バディウはリセ・ ルイ・ル・グランに在籍した後、高等師範学校(École Normale Supérieure)に入学(1955-1960)。 [5]1960年、ジョルジュ・カンギルヘムのためにスピノザに関するdiplôme d'études supérieures [fr](修士論文にほぼ相当)を執筆(テーマは「スピノザの倫理学の最初の2冊における実証の構造」、「Structures démonstratives dans les deux premiers livres de l'Éthique de Spinoza」)。 [1963年からランスのリセで教鞭をとり、劇作家(哲学者)フランソワ・ルノーと親交を深め[7]、2冊の小説を発表した後、1969年にランス大学文 学部(collège littéraire universitaire)[8]、パリ第8大学(ヴァンセンヌ・サン・ドニ)に移る。 [9]バディウは早くから政治活動に積極的で、統一社会党(PSU)の創設メンバーの一人であった。PSUは特にアルジェリアの脱植民地化のための闘争で 活躍した。1964年に最初の小説『アルマゲステス』を執筆。1967年、ルイ・アルチュセールによって組織された研究グループに参加し、ジャック・ラカ ンからますます影響を受けるようになり、『カイエ・プール・ラン・アナリシス』誌の編集委員となる[9]。その頃、彼は「(ラカンの理論とともに)数学と 論理学の確固たる基礎を持っていた」[9]。 1968年5月の学生蜂起はバディウの極左へのコミットメントを強め、彼はフランス共産主義者同盟(UCFml)のような過激なグループに参加するように なる。バディウ自身の言葉を借りれば、UCFmlは「ナタシャ・ミシェル、シルヴァン・ラザロ、私、そしてかなりの数の若者たちによって1969年末に設 立された毛沢東主義組織」である[10]。この時期、バディウは反文化思想の砦であった新設のパリ第8大学(ヴァンセンヌ・サン・ドニ)の教授陣に加わっ た。そこでバディウは、同僚のジル・ドゥルーズやジャン=フランソワ・リオタールと熾烈な知的論争を繰り広げた。彼らの哲学的著作は、科学的マルクス主義 というアルチュセールのプログラムから逸脱した不健全なものだとバディウは考えていた。 1980年代、アルチュセールの構造的マルクス主義とラカンの精神分析がともに衰退していく中(ラカンが死に、アルチュセールが精神病院に収容された 後)、バディウは『Théorie du sujet』(1982年)や大作『存在と出来事』(1988年)など、より専門的で抽象的な哲学書を出版した。それにもかかわらず、バディウはアルチュ セールやラカンを放棄したことはなく、マルクス主義や精神分析への共感的な言及は最近の著作(特に『Petit panthéon portatif/ポケット・パンテオン』)では珍しくない[11][12]。 1999年にENSの現職に就任。国際哲学コレージュ(Collège International de Philosophie)など、他の多くの機関とも関係がある。前述のように、1985年に毛沢東主義UCFmlの同志たちとともに設立した L'Organisation Politique [fr]のメンバーであった。この組織は2007年に解散した(前文でリンクしたフランスのウィキペディアの記事)。2002年には、イヴ・デュルーや彼 の元教え子であるクエンティン・メイヤスーとともに、現代フランス哲学研究センター(Centre International d'Etude de la Philosophie Française Contemporaine)の共同設立者でもある[13]。 この10年間で、『倫理学』、『ドゥルーズ』、『哲学宣言』、『メタ政治学』、『存在と出来事』など、バディウの作品が英訳される機会が増えている。バ ディウの小品も同様に、『Lacanian Ink』、『New Left Review』、『Radical Philosophy』、『Cosmos and History』、『Parrhesia』といったアメリカやイギリスの定期刊行物に掲載されている。現代ヨーロッパの哲学者としては珍しく、彼の作品はインド、コンゴ民主共和国、南アフリカ共和国などの過激派に取り上げられることが多くなっている[要出典]。 2014年から15年にかけて、バディウはグローバル高等研究センターの名誉総裁を務めていた[14]。 |

| Key concepts This section possibly contains original research. Please improve it by verifying the claims made and adding inline citations. Statements consisting only of original research should be removed. (August 2018) (Learn how and when to remove this message) Badiou makes repeated use of several concepts throughout his philosophy, which he discerns from close readings of the philosophical literature from the classical period. His own method cannot be fully understood if it is not situated within the tradition of French academic philosophy. Badiou's work engages a detailed decrypting of texts, in line with philosophers such as Foucault, Deleuze, Balibar, Bourdieu, Derrida, Bouveresse and Engel, all of whom he studied with at the Ecole Normale Superieure. One of the aims of his thought is to show that his categories of truth are useful for any type of philosophical critique. Therefore, he uses them to interrogate art and history as well as ontology and scientific discovery. Johannes Thumfart argues that Badiou's philosophy can be regarded as a contemporary reinterpretation of Platonism.[15] Conditions According to Badiou, philosophy is suspended from four conditions (art, love, politics, and science), each of them fully independent "truth procedures." (For Badiou's notion of truth procedures, see below.) Badiou consistently maintains throughout his work (but most systematically in Manifesto for Philosophy) that philosophy must avoid the temptation to suture itself ('sew itself', that is, to hand over its entire intellectual effort) to any of these independent truth procedures. When philosophy does suture itself to one of its conditions (and Badiou argues that the history of philosophy during the nineteenth and twentieth centuries is primarily a history of sutures), what results is a philosophical "disaster." Consequently, philosophy is, according to Badiou, a thinking of the compossibility of the several truth procedures, whether this is undertaken through the investigation of the intersections between distinct truth procedures (the intersection of art and love in the novel, for instance), or whether this is undertaken through the more traditionally philosophical work of addressing categories like truth or the subject (concepts that are, as concepts, external to the individual truth procedures, though they are functionally operative in the truth procedures themselves). For Badiou, when philosophy addresses the four truth procedures in a genuinely philosophical manner, rather than through a suturing abandonment of philosophy as such, it speaks of them with a theoretical terminology that marks its philosophical character: "inaesthetics" rather than art; metapolitics rather than politics; ontology rather than science; etc. Truth, for Badiou, is a specifically philosophical category. While philosophy's several conditions are, on their own terms, "truth procedures" (i.e., they produce truths as they are pursued), it is only philosophy that can speak of the several truth procedures as truth procedures. (The lover, for instance, does not think of her love as a question of truth, but simply and rightly as a question of love. Only the philosopher sees in the true lover's love the unfolding of a truth.) Badiou has a very rigorous notion of truth, one that is strongly against the grain of much of contemporary European thought. Badiou at once embraces the traditional modernist notion that truths are genuinely invariant (always and everywhere the case, eternal and unchanging) and the incisively postmodernist notion that truths are constructed through processes. Badiou's theory of truth, exposited throughout his work, accomplishes this strange mixture by uncoupling invariance from self-evidence (such that invariance does not imply self-evidence), as well as by uncoupling constructedness from relativity (such that constructedness does not lead to relativism). The idea, here, is that a truth's invariance makes it genuinely indiscernible: because a truth is everywhere and always the case, it passes unnoticed unless there is a rupture in the laws of being and appearance, during which the truth in question becomes, but only for a passing moment, discernible. Such a rupture is what Badiou calls an event, according to a theory originally worked out in Being and Event and fleshed out in important ways in Logics of Worlds. The individual who chances to witness such an event, if he is faithful to what he has glimpsed, can then introduce the truth by naming it into worldly situations. For Badiou, it is by positioning oneself to the truth of an event that a human animal becomes a subject; subjectivity is not an inherent human trait. According to a process or procedure that subsequently unfolds only if those who subject themselves to the glimpsed truth continue to be faithful in the work of announcing the truth in question, genuine knowledge is produced (knowledge often appears in Badiou's work under the title of the "veridical"). While such knowledge is produced in the process of being faithful to a truth event, for Badiou, knowledge, in the figure of the encyclopedia, always remains fragile, subject to what may yet be produced as faithful subjects of the event produce further knowledge. According to Badiou, truth procedures proceed to infinity, such that faith (fidelity) outstrips knowledge. (Badiou, following both Lacan and Heidegger, distances truth from knowledge.) The dominating ideology of the day, which Badiou terms "democratic materialism," denies the existence of truth and only recognizes "bodies" and "languages." Badiou proposes a turn towards the "materialist dialectic," which recognizes that there are only bodies and languages, except there are also truths. Inaesthetic In Handbook of Inaesthetics Badiou both draws on the original Greek meaning and the later Kantian concept of "aesthesis" as "material perception" and coins the phrase "inaesthetic" to refer to a concept of artistic creation that denies "the reflection/object relation" yet, at the same time, in reaction against the idea of mimesis, or poetic reflection of "nature", he affirms that art is "immanent" and "singular". Art is immanent in the sense that its truth is given in its immediacy in a given work of art, and singular in that its truth is found in art and art alone – hence reviving the ancient materialist concept of "aesthesis". His view of the link between philosophy and art is tied into the motif of pedagogy, which he claims functions so as to "arrange the forms of knowledge in a way that some truth may come to pierce a hole in them". He develops these ideas with examples from the prose of Samuel Beckett and the poetry of Stéphane Mallarmé and Fernando Pessoa (who he argues has developed a body of work that philosophy is currently incapable of incorporating), among others. Being and Event The major propositions of Badiou's philosophy all find their basis in Being and Event, in which he continues his attempt (which he began in Théorie du sujet) to reconcile a notion of the subject with ontology, and in particular post-structuralist and constructivist ontologies.[16] A frequent criticism of post-structuralist work is that it prohibits, through its fixation on semiotics and language, any notion of a subject. Badiou's work is, by his own admission,[17] an attempt to break out of contemporary philosophy's fixation upon language, which he sees almost as a straitjacket. This effort leads him, in Being and Event, to combine rigorous mathematical formulae with his readings of poets such as Mallarmé and Hölderlin and religious thinkers such as Pascal. His philosophy draws upon both 'analytical' and 'continental' traditions. In Badiou's own opinion, this combination places him awkwardly relative to his contemporaries, meaning that his work had been only slowly taken up.[18] Being and Event offers an example of this slow uptake, in fact: it was translated into English only in 2005, a full seventeen years after its French publication. As is implied in the title of the book, two elements mark the thesis of Being and Event: the place of ontology, or 'the science of being qua being' (being in itself), and the place of the event – which is seen as a rupture in being – through which the subject finds realization and reconciliation with truth. This situation of being and the rupture which characterizes the event are thought in terms of set theory, and specifically Zermelo–Fraenkel set theory with the axiom of choice. In short, the event is a truth caused by a hidden "part" or set appearing within existence; this part escapes language and known existence, and thus being itself lacks the terms and resources to fully process the event. Mathematics as ontology This section possibly contains original research. Please improve it by verifying the claims made and adding inline citations. Statements consisting only of original research should be removed. (December 2014) (Learn how and when to remove this message) For Badiou the problem which the Greek tradition of philosophy has faced and never satisfactorily dealt with is that while beings themselves are plural, and thought in terms of multiplicity, being itself is thought to be singular; that is, it is thought in terms of the one. He proposes as the solution to this impasse the following declaration: that the One is not (l'Un n'est pas). This is why Badiou accords set theory (the axioms of which he refers to as the "ideas of the multiple") such stature, and refers to mathematics as the very place of ontology: Only set theory allows one to conceive a 'pure doctrine of the multiple'. Set theory does not operate in terms of definite individual elements in groupings but only functions insofar as what belongs to a set is of the same relation as that set (that is, another set too). What individuates a set, therefore, is not an existential positive proposition, but other multiples whose properties (i.e., structural relations) validate its presentation. The structure of being thus secures the regime of the count-as-one. So if one is to think of a set – for instance, the set of people, or humanity – as counting as one, the multiple elements which belong to that set are secured as one consistent concept (humanity), but only in terms of what does not belong to that set. What is crucial for Badiou is that the structural form of the count-as-one, which makes multiplicities thinkable, implies (somehow or other) that the proper name of being does not belong to an element as such (an original 'one'), but rather the void set (written Ø), the set to which nothing (not even the void set itself) belongs. It may help to understand the concept 'count-as-one' if it is associated with the concept of 'terming': a multiple is not one, but it is referred to with 'multiple': one word. To count a set as one is to mention that set. How the being of terms such as 'multiple' does not contradict the non-being of the one can be understood by considering the multiple nature of terminology: for there to be a term without there also being a system of terminology, within which the difference between terms gives context and meaning to any one term, is impossible. 'Terminology' implies precisely difference between terms (thus multiplicity) as the condition for meaning. The idea of a term without meaning is incoherent, the count-as-one is a structural effect or a situational operation; it is not an event of 'truth'. Multiples which are 'composed' or 'consistent' are count-effects. 'Inconsistent multiplicity' [meaning?] is [somehow or other] 'the presentation of presentation.' Badiou's use of set theory in this manner is not just illustrative or heuristic. Badiou uses the axioms of Zermelo–Fraenkel set theory to identify the relationship of being to history, Nature, the State, and God. Most significantly this use means that (as with set theory) there is a strict prohibition on self-belonging; a set cannot contain or belong to itself. This results from the axiom of foundation – or the axiom of regularity – which enacts such a prohibition (cf. p. 190 in Being and Event). (This axiom states that every non-empty set A contains an element y that is disjoint from A.) Badiou's philosophy draws two major implications from this prohibition. Firstly, it secures the inexistence of the 'one': there cannot be a grand overarching set, and thus it is fallacious to conceive of a grand cosmos, a whole Nature, or a Being of God. Badiou is therefore – against Georg Cantor, from whom he draws heavily – staunchly atheist. However, secondly, this prohibition prompts him to introduce the event. Because, according to Badiou, the axiom of foundation 'founds' all sets in the void, it ties all being to the historico-social situation of the multiplicities of de-centred sets – thereby effacing the positivity of subjective action, or an entirely 'new' occurrence. And whilst this is acceptable ontologically, it is unacceptable, Badiou holds, philosophically. Set theory mathematics has consequently 'pragmatically abandoned' an area which philosophy cannot. And so, Badiou argues, there is therefore only one possibility remaining: that ontology can say nothing about the event. Several critics have questioned Badiou's use of mathematics. Mathematician Alan Sokal and physicist Jean Bricmont write that Badiou proposes, with seemingly "utter seriousness," a blending of psychoanalysis, politics and set theory that they contend is preposterous.[19] Similarly, philosopher Roger Scruton has questioned Badiou's grasp of the foundation of mathematics, writing in 2012: There is no evidence that I can find in Being and Event that the author really understands what he is talking about when he invokes (as he constantly does) Georg Cantor's theory of transfinite cardinals, the axioms of set theory, Gödel's incompleteness proof or Paul Cohen's proof of the independence of the continuum hypothesis. When these things appear in Badiou's texts it is always allusively, with fragments of symbolism detached from the context that endows them with sense, and often with free variables and bound variables colliding randomly. No proof is clearly stated or examined, and the jargon of set theory is waved like a magician's wand, to give authority to bursts of all but unintelligible metaphysics.[20] An example of a critique from a mathematician's point of view is the essay 'Badiou's Number: A Critique of Mathematics as Ontology' by Ricardo L. Nirenberg and David Nirenberg,[21] which takes issue in particular with Badiou's matheme of the Event in Being and Event, which has already been alluded to in respect of the 'axiom of foundation' above. Nirenberg and Nirenberg write: Rather than being defined in terms of objects previously defined, ex is here defined in terms of itself; you must already have it in order to define it. Set theorists call this a not-well-founded set. This kind of set never appears in mathematics – not least because it produces an unmathematical mise-en-abîme: if we replace ex inside the bracket by its expression as a bracket, we can go on doing this forever – and so can hardly be called "a matheme."' The event and the subject Badiou again turns here to mathematics and set theory – Badiou's language of ontology – to study the possibility of an indiscernible element existing extrinsically to the situation of ontology. He employs the strategy of the mathematician Paul J. Cohen, using what are called the conditions of sets. These conditions are thought of in terms of domination, a domination being that which defines a set. (If one takes, in binary language, the set with the condition 'items marked only with ones', any item marked with zero negates the property of the set. The condition which has only ones is thus dominated by any condition which has zeros in it [cf. pp. 367–371 in Being and Event].) Badiou reasons using these conditions that every discernible (nameable or constructible) set is dominated by the conditions which don't possess the property that makes it discernible as a set. (The property 'one' is always dominated by 'not one'.) These sets are, in line with constructible ontology, relative to one's being-in-the-world and one's being in language (where sets and concepts, such as the concept 'humanity', get their names). However, he continues, the dominations themselves are, whilst being relative concepts, not necessarily intrinsic to language and constructible thought; rather one can axiomatically define a domination – in the terms of mathematical ontology – as a set of conditions such that any condition outside the domination is dominated by at least one term inside the domination. One does not necessarily need to refer to constructible language to conceive of a 'set of dominations', which he refers to as the indiscernible set, or the generic set. It is therefore, he continues, possible to think beyond the strictures of the relativistic constructible universe of language, by a process Cohen calls forcing. And he concludes in following that while ontology can mark out a space for an inhabitant of the constructible situation to decide upon the indiscernible, it falls to the subject – about which the ontological situation cannot comment – to nominate this indiscernible, this generic point; and thus nominate, and give name to, the undecidable event. Badiou thereby marks out a philosophy by which to refute the apparent relativism or apoliticism in post-structuralist thought. Badiou's ultimate ethical maxim is therefore one of: 'decide upon the undecidable'. It is to name the indiscernible, the generic set, and thus name the event that re-casts ontology in a new light. He identifies four domains in which a subject (who, it is important to note, becomes a subject through this process) can potentially witness an event: love, science, politics and art. By enacting fidelity to the event within these four domains one performs a 'generic procedure', which in its undecidability is necessarily experimental, and one potentially recasts the situation in which being takes place. Through this maintenance of fidelity, truth has the potentiality to emerge. In line with his concept of the event, Badiou maintains, politics is not about politicians, but activism based on the present situation and the evental [sic] (his translators' neologism) rupture. So too does love have this characteristic of becoming anew. Even in science the guesswork that marks the event is prominent. He vigorously rejects the tag of 'decisionist' (the idea that once something is decided it 'becomes true'), but rather argues that the recasting of a truth comes prior to its veracity or verifiability. As he says of Galileo (p. 401): When Galileo announced the principle of inertia, he was still separated from the truth of the new physics by all the chance encounters that are named in subjects such as Descartes or Newton. How could he, with the names he fabricated and displaced (because they were at hand – 'movement', 'equal proportion', etc.), have supposed the veracity of his principle for the situation to-come that was the establishment of modern science; that is, the supplementation of his situation with the indiscernible and unfinishable part that one has to name 'rational physics'? While Badiou is keen to reject an equivalence between politics and philosophy, he correlates nonetheless his political activism and skepticism toward the parliamentary-democratic process with his philosophy, based around singular, situated truths, and potential revolutions. |

キーコンセプト このセクションにはオリジナルの研究が含まれている可能性があります。主張を検証し、インライン引用を追加することで改善してください。独自研究のみからなる記述は削除してください。(2018年8月)(このメッセージを削除する方法とタイミングを学ぶ) バディウは、古典期からの哲学文献を精読して見出したいくつかの概念を、自身の哲学の至るところで繰り返し用いている。彼自身の方法は、フランスのアカデ ミックな哲学の伝統の中に位置づけられなければ、完全に理解することはできない。バディウの仕事は、彼がエコール・ノルマル・シュペリュールで共に学んだ フーコー、ドゥルーズ、バリバール、ブルデュー、デリダ、ブーヴレス、エンゲルといった哲学者たちと同様に、テクストの詳細な解読に取り組んでいる。 彼の思想の目的のひとつは、彼の真理のカテゴリーがあらゆるタイプの哲学的批評に有用であることを示すことである。そのため、彼は芸術や歴史、存在論や科 学的発見を問うためにそれらを用いている。ヨハネス・トゥムファートは、バディウの哲学はプラトン主義の現代的な再解釈とみなすことができると論じている [15]。 条件 バディウによれば、哲学は4つの条件(芸術、愛、政治、科学)から中断されており、それぞれが完全に独立した 「真理の手続き 」である。(バディウは一貫して、哲学はこれらの独立した真理手続きのいずれかに自らを縫合する(「自らを縫う」、つまり知的努力のすべてを委ねる)誘惑 を避けなければならないと主張している(バディウの真理手続きの概念については以下を参照)。バディウは、19世紀から20世紀にかけての哲学の歴史は、 主として縫合の歴史であると論じている。その結果、バディウによれば、哲学とは、複数の真理手続き間の交差点(例えば、小説における芸術と愛の交差点)の 調査を通じて行われるにせよ、真理や主体といったカテゴリー(真理手続き自体には機能的に作用するが、概念としては個々の真理手続きの外部にある)を扱 う、より伝統的な哲学的作業を通じて行われるにせよ、複数の真理手続きの共存可能性を考えることである。バディウにとって、哲学が4つの真理手続きに純粋 に哲学的なやり方で取り組むとき、むしろ哲学を放棄することによってではなく、哲学はその哲学的性格を示す理論的な用語を使ってそれについて語るのであ る: 芸術ではなく「無美学」、政治ではなく「形而上学」、科学ではなく「存在論」などである。 バディウにとって真理とは、特に哲学的なカテゴリーである。哲学の諸条件は、それ自体としては「真理手続き」(すなわち、追求されるままに真理を生み出 す)であるが、いくつかの真理手続きを真理手続きとして語ることができるのは哲学だけである。(たとえば恋人は、自分の愛を真理の問題としてではなく、単 純に正しく愛の問題として考える。哲学者だけが、真の恋人の愛に真理の展開を見るのである)。バディウは真理について非常に厳格な概念を持っており、それ は現代のヨーロッパ思想の多くに強く反している。バディウは、真理は純粋に不変であるという伝統的なモダニズムの考え方(常に、どこでもそうであり、永遠 であり、不変である)と、真理はプロセスを通じて構築されるというポストモダニズムの鋭い考え方を同時に受け入れている。バディウの真理論は、その著作を 通して明らかにされているが、不変性と自証性を切り離し(不変性が自証性を意味しないように)、また構築性と相対性を切り離す(構築性が相対主義につなが らないように)ことで、この奇妙な混合を実現している。 真理はどこにでもあり、常にそうであるため、存在と外観の法則に断絶が生じない限り、真理は気づかれずに通り過ぎてしまう。このような断絶を、バディウは 「出来事」と呼んでいる。『存在と出来事』(原題『Being and Event』)で展開され、『世界の論理学』(原題『Logics of Worlds』)で重要な形で具体化された理論によれば、このような断絶は「出来事」である。そのような出来事に偶然立ち会った個人は、もし自分が垣間見 たものに忠実であるならば、それを世俗の状況に名づけることによって、真理を導入することができる。バディウにとって、ある出来事の真理に自らを位置づけ ることによって、人間という動物は主体となる。垣間見た真理に身を委ねる者が、問題の真理を告知する作業に忠実であり続ける場合にのみ、その後に展開され る過程や手続きによれば、真の知識が生み出される(バディウの作品にはしばしば「真実的」というタイトルで知識が登場する)。このような知識は、真実の出 来事に忠実である過程で生み出されるが、バディウにとって知識は、百科事典の姿において、常に脆弱なままであり、出来事に忠実な主体がさらなる知識を生み 出す際に、まだ生み出されるかもしれないものに左右される。バディウによれば、真理の手続きは無限大に進行し、信仰(忠実さ)は知識を凌駕する。(バディ ウはラカンやハイデガーに倣い、真理を知識から遠ざけている)バディウが「民主主義的唯物論」と呼ぶ現代の支配的なイデオロギーは、真理の存在を否定し、 「身体 」と 「言語 」だけを認めている。バディウは「唯物弁証法」への転換を提案する。この弁証法では、身体と言語しか存在しないが、真理も存在することを認める。 非耽美的(非美学) バディウは『Handbook of Inaesthetics』の中で、「物質的知覚」としてのギリシャ語の原義と、後のカント派の「美学」の概念を引き、「反省と対象の関係」を否定する芸 術創造の概念を指す「非美学的(inaesthetic)」という造語を生み出しているが、同時に、「自然」のミメーシス(詩的反省)の考え方に反発し て、芸術は「内在的」で「特異」であると断言している。芸術は内在的であり、その真理は芸術と芸術の中にのみ見出されるという意味で特異である。哲学と芸 術の結びつきについての彼の見解は、教育学というモチーフと結びついている。教育学は、「何らかの真理がそこに穴を開けることができるように、知識の形式 を整える」ために機能すると彼は主張する。サミュエル・ベケットの散文、ステファン・マラルメやフェルナンド・ペソアの詩(彼は哲学が現在取り入れること のできない作品群を発展させてきたと主張する)などを例に、こうした考えを展開している。 存在と出来事 バディウの哲学の主要な命題はすべて『存在と出来事』にその基礎がある。『存在と出来事』では、主体という概念と存在論、特にポスト構造主義や構成主義の 存在論とを調和させようとする試み(『Théorie du sujet』で始めた)を続けている。バディウの仕事は、彼自身が認めているように[17]、現代哲学の言語への固執から脱却しようとする試みであり、彼 はそれをほとんど拘束衣とみなしている。この試みによって、『存在と出来事』では、マラルメやヘルダーリンのような詩人やパスカルのような宗教思想家の読 解に、厳密な数式を組み合わせている。バディウの哲学は、「分析的」な伝統と「大陸的」な伝統の両方に依拠している。バディウ自身の見解では、この組み合 わせは同時代の哲学者たちと比べてバディウを不器用な存在に位置づけており、つまりバディウの仕事はゆっくりとしか取り上げられなかったのである [18]。『存在と出来事』は、このゆっくりとした取り上げられ方の一例を示している。 すなわち、存在論、すなわち「存在それ自体としての存在の科学」(それ自体における存在)の位置と、主体が実現と真理との和解を見出す、存在の断絶とみな される出来事の位置である。このような存在の状況と、出来事を特徴づける断絶は、集合論、特に選択の公理を持つツェルメロ=フレンケル集合論の観点から考 えられている。要するに、この出来事は、存在の中に現れる隠された「部分」あるいは集合によって引き起こされる真理であり、この部分は言語や既知の存在を 逃れ、したがって存在そのものが、この出来事を完全に処理するための条件や資源を欠いているのである。 存在論としての数学 このセクションにはオリジナルの研究が含まれている可能性があります。主張を検証し、インライン引用を追加することで改善してください。独自研究のみからなる記述は削除してください。(2014年12月)(このメッセージを削除する方法とタイミングを学ぶ) バディウにとって、ギリシア哲学の伝統が直面し、決して満足に対処してこなかった問題とは、存在者自身が複数であり、複数性の観点から思考される一方で、 存在者自身は単数であると考えられていること、すなわち、それは一の観点から思考されていることである。彼はこの行き詰まりの解決策として、次のような宣 言を提案している。バディウが集合論(その公理を彼は「多重のイデア」と呼ぶ)を高く評価し、数学をまさに存在論の場と呼ぶのはこのためである: 集合論だけが、「多重の純粋な教義」を構想することを可能にする。集合論は、グループ化された個々の要素という観点から機能するのではなく、ある集合に属 するものがその集合と同じ関係にある(つまり、別の集合でもある)限りにおいてのみ機能する。したがって、集合を個別化するものは、実存的な肯定的命題で はなく、その性質(すなわち構造的関係)がその提示を正当化する他の多重項である。こうして、存在の構造は、カウント・アズ・ワンの体制を保証する。だか ら、ある集合--たとえば、人々の集合、あるいは人間性--を一と数えるものとして考えるならば、その集合に属する複数の要素は、一つの一貫した概念(人 間性)として担保されるが、その集合に属さないものについては担保されない。バディウにとって極めて重要なのは、多義性を思考可能なものにする「一として 数える」という構造形式が、(何らかの形で)存在という固有名詞が、そのような要素(本来の「一」)に属するのではなく、むしろ空集合(Øと書かれる)、 つまり何ものにも(空集合それ自体にも)属さない集合に属することを暗示しているということである。この概念を「項対立」の概念と関連づけると、「1とし て数える」という概念を理解しやすくなるかもしれない。倍数は1ではないが、「倍数」、つまり1つの単語で呼ばれる。ある集合をひとつと数えることは、そ の集合について言及することである。multiple」のような用語が存在することが、「one」の非存在といかに矛盾しないかは、用語の多重性を考慮す ることで理解できる。用語間の差異がどの用語にも文脈と意味を与える用語体系が存在せずに用語が存在することは不可能である。用語」は、意味の条件とし て、用語間の差異(したがって多重性)を正確に意味する。意味のない用語という考えは支離滅裂であり、カウント・アズ・ワンは構造的効果や状況的操作で あって、「真理」の出来事ではない。構成されている」あるいは「一貫している」多重性は、カウント効果である。一貫性のない多重性」[意味か?]は[何ら かの形で]「提示の提示」である。 バディウがこのように集合論を用いるのは、単なる例示や発見的なものではない。バディウはツェルメロ=フレンケル集合論の公理を使って、歴史、自然、国 家、神と存在の関係を明らかにしている。最も重要なのは、この使用は、(集合論と同様に)自己帰属が厳密に禁止されていることを意味する。これは、このよ うな禁止を規定する基礎の公理、あるいは規則性の公理に起因する(『存在と出来事』の190ページを参照)。(この公理は、空でない集合Aはすべて、Aか ら離散する要素yを含むとする)。バディウの哲学は、この禁止から2つの大きな意味を引き出す。すなわち、壮大な包括的集合は存在し得ず、したがって、壮 大なコスモス、自然全体、神の存在を考えることは誤りである。したがって、バディウは、彼が大いに参考にしているゲオルク・カントールに対して、断固とし た無神論者なのである。しかし、第二に、この禁止令は彼に出来事の導入を促す。というのも、バディウによれば、基礎の公理はすべての集合を空虚の中に「発 見」し、すべての存在を、中心を失った集合の多重性という歴史的・社会的状況に結びつけるからである。そして、これは存在論的には容認できるが、哲学的に は容認できないとバディウは主張する。集合論数学は結果として、哲学では不可能な領域を「プラグマティックに放棄」したのである。つまり、存在論は出来事 について何も語ることができないということである。 何人かの批評家は、バディウの数学の使用に疑問を呈している。数学者のアラン・ソーカルと物理学者のジャン・ブリクモンは、バディウは精神分析、政治、集合論の融合を一見「全くの本気」で提案しているが、それはとんでもないことだと書いている: ゲオルク・カントールの超限枢機卿の理論、集合論の公理、ゲーデルの不完全性証明、ポール・コーエンの連続体仮説の独立性の証明などを(彼が常に引き合い に出すように)引き合いに出すとき、著者が自分が何を言っているのか本当に理解しているという証拠は、『存在と事象』の中には見当たらない。バディウのテ キストにこれらのものが登場するときは、常に暗示的であり、意味を与える文脈から切り離された象徴の断片であり、しばしば自由変数と束縛変数がランダムに 衝突している。証明は明言されず、検討もされず、集合論の専門用語は魔術師の杖のように振られ、意味不明な形而上学の炸裂に権威を与えている[20]。 数学者の視点からの批評の例としては、エッセイ「バディウの数」がある: リカルド・L・ニレンベルグとデイヴィッド・ニレンベルグによる「存在論としての数学批判」[21]は、特に『存在と出来事』におけるバディウの「出来 事」の主題を問題にしており、この主題は上述の「基礎の公理」に関してすでに言及されている。NirenbergとNirenbergはこう書いている: 定義するためには、それをすでに持っていなければならない。集合論者はこれをnot-well-founded setと呼ぶ。このような集合が数学に登場することはない--少なくとも、非数学的なミス・エン・アビームを生み出すからである:括弧の中のexを括弧と してのexの表現に置き換えれば、これを永遠に続けることができるからである。 出来事と主体 バディウはここで再び数学と集合論--バディウの存在論の言語--に目を向け、存在論の状況に対して外在的に存在する無分別な要素の可能性を研究する。彼 は数学者ポール・J・コーエンの戦略を採用し、集合の条件と呼ばれるものを用いる。これらの条件は支配の観点から考えられており、支配とは集合を定義する ものである。(2進数の言葉で、'onesとマークされた項目のみ'という条件を持つ集合を考えると、0とマークされた項目はその集合の性質を否定するこ とになる。こうして、「1」のみを持つ条件は、「0」を持つあらゆる条件に支配される[『存在と出来事』の367-371頁を参照]。バディウはこれらの 条件を用いて、すべての識別可能な(名付け可能な、あるいは構成可能な)集合は、それを集合として識別可能にする性質を持たない条件によって支配されてい ると理由づける。(これらの集合は、構成可能な存在論に沿って、世界における自分の存在と言語における自分の存在(「人間性」という概念などの集合や概念 がその名前を得る場所)に相対するものである。) 支配は、相対的な概念である一方で、必ずしも言語や構築可能な思考に内在するものではない。むしろ、数学的存在論の観点から、支配の外側にあるいかなる条 件も、支配の内側にある少なくとも一つの項によって支配されるような条件の集合として、支配を公理的に定義することができる。支配の集合」を考えるのに、 構成可能な言語を参照する必要は必ずしもない。それゆえ、コーエンが「強制」と呼ぶプロセスによって、相対主義的な構成可能な言語の世界の厳しさを超えて 思考することが可能なのだ、と彼は続ける。そして、存在論は、構成可能な状況の住人が無分別なものを決定するための空間を示すことができるが、この無分別 なもの、つまり一般的な点を指名し、決定不可能な出来事に名前を与えることは、存在論的状況がコメントすることのできない主体に委ねられている、と結論づ ける。バディウはそれによって、ポスト構造主義思想における見かけの相対主義や非政治主義に反論するための哲学を示す。 従って、バディウの究極の倫理的格言は次のようなものである: 決定不可能なものを決定する」。それは、見分けがつかないもの、一般的な集合に名前をつけることであり、そうして存在論を新たな光で捉え直す出来事に名前 をつけることである。彼は、主体(このプロセスを通じて主体になることが重要である)が出来事を目撃できる可能性のある4つの領域を特定する:愛、科学、 政治、芸術。これらの4つの領域で出来事への忠実性を実現することによって、人は「一般的な手続き」を行うが、それはその決定不可能性において必然的に実 験的であり、人は「存在」が起こる状況を潜在的に再構成する。この忠実性の維持を通じて、真理は潜在的に出現する。 バディウは、政治とは政治家のことではなく、現状と出来事(訳者の新造語)の断絶に基づく活動主義であると主張する。愛もまた、新たに生まれ変わるという 特徴を持っている。科学でさえも、事象を示す当て推量が目立つ。彼は「決定論者」(いったん何かが決定されれば、それが「真実になる」という考え方)とい うタグを激しく否定し、むしろ真理の再構成は、その真実性や検証可能性に先立って行われると主張する。彼はガリレオについてこう述べている (p.401): ガリレオが慣性の原理を発表したとき、彼はデカルトやニュートンのような題材に名を連ねるあらゆる偶然の出会いによって、新しい物理学の真理からまだ隔て られていた。運動」、「均等な割合」など、手近にあったからこそ)彼が捏造し、置き換えた名前を使って、近代科学の確立という来るべき状況、つまり、「合 理的物理学」と名づけなければならないような、見分けがつかず、完結しない部分による彼の状況の補完に対して、どのように自分の原理の真実性を想定できた だろうか。 バディウは政治と哲学の等価性を否定することに熱心だが、それにもかかわらず、彼は政治的活動主義と議会制民主主義のプロセスに対する懐疑を、特異で、位置づけられた真理と潜在的な革命を軸とする彼の哲学と関連付けている。 |

| L'Organisation Politique Alain Badiou is a founding member (along with Natacha Michel and Sylvain Lazarus) of the militant French political organisation L'Organisation Politique, which was active from 1985 until it disbanded in 2007.[22] It called itself a post-party organization concerned with direct popular intervention in a wide range of issues (including immigration, labor, and housing). In addition to numerous writings and interventions, L'Organisation Politique highlighted the importance of developing political prescriptions concerning undocumented migrants (les sans papiers), stressing that they must be conceived primarily as workers and not immigrants.[23] |

政治組織 アラン・バディウは、1985年から2007年に解散するまで活動したフランスの過激な政治組織「組織政治」の創設メンバー(ナタシャ・ミシェル、シル ヴァン・ラザルスとともに)である。数多くの著作や介入に加え、L'Organisation Politiqueは、非正規移民(les sans papiers)に関する政治的処方箋を策定することの重要性を強調し、彼らは移民ではなく、主として労働者として概念されなければならないと強調した [23]。 |

| Public controversies Anti-Semitism accusation and response In 2005, a fierce controversy in Parisian intellectual life erupted after the publication of Badiou's Circonstances 3: Portées du mot 'juif' ("The Uses of the Word 'Jew'").[24] This book generated a strong response, and the wrangling became a cause célèbre with articles going back and forth in the French newspaper Le Monde and in the cultural journal Les Temps modernes. Linguist and Lacanian philosopher Jean-Claude Milner, a past president of Collège international de philosophie, accused Badiou of anti-Semitism.[25] Badiou forcefully rebutted this charge, declaring that his accusers often conflate a nation-state with religious preference and will label as anti-Semitic anyone who objects to this tendency: "It is wholly intolerable to be accused of anti-Semitism by anyone for the sole reason that, from the fact of the extermination, one does not conclude as to the predicate "Jew" and its religious and communitarian dimension that it receive some singular valorization – a transcendent annunciation! – nor that Israeli exactions, whose colonial nature is patent and banal, be specially tolerated. I propose that nobody any longer accept, publicly or privately, this type of political blackmail."[26] Badiou characterizes the state of Israel as "neither more nor less impure than all states", but objects to "its exclusive identitarian claim to be a Jewish state, and the way it draws incessant privileges from this claim, especially when it comes to trampling underfoot what serves us as international law." For example, he continues, "The Islamic states are certainly no more progressive as models than the various versions of the 'Arab nation' were. Everyone agrees, it seems, on the point that the Taliban do not embody the path of modernity for Afghanistan.”[26] A modern democracy, he writes, must count all its residents as citizens, and "there is no acceptable reason to exempt the state of Israel from that rule. The claim is sometimes made that this state is the only 'democratic' state in the region. But the fact that this state presents itself as a Jewish state is directly contradictory."[26] Badiou is optimistic that ongoing political problems can be resolved by de-emphasizing the communitarian religious dimension: "The signifier 'Palestinian' or 'Arab' should not be glorified any more than is permitted for the signifier 'Jew.' As a result, the legitimate solution to the Middle East conflict is not the dreadful institution of two barbed-wire states. The solution is the creation of a secular and democratic Palestine...which would show that it is perfectly possible to create a place in these lands where, from a political point of view and regardless of the apolitical continuity of customs, there is 'neither Arab nor Jew.' This will undoubtedly demand a regional Mandela."[26] Sarkozy pamphlet Alain Badiou gained notoriety in 2007 with his pamphlet The Meaning of Sarkozy (De quoi Sarkozy est-il le nom?), which quickly sold 60,000 copies, whereas for 40 years the sales of his books had oscillated between 2,000 and 6,000 copies.[27] As Rafael Bahr pointed out at the time (in 2009), Badiou despised Sarkozy and barely could write his name. Instead, Badiou usually called Sarkozy "the Rat Man" throughout The Meaning of Sarkozy.[28] Steven Poole also pointed out that this characterization (Rat Man) brought charges of antisemitism against Badiou.[29] But as Bahr notes, the controversy went beyond antisemitism, striking at the heart of what it means to be French: “[Badiou] sees Sarkozy as the embodiment of a strain of moral cowardice in French politics, in which the defining moment was the installation of Marshal Pétain as head of the pro-Nazi collaborationist government. For Badiou, Sarkozy is a symbol of "transcendent Pétainism".”[28] Mark Fisher was impressed with Badiou’s efforts: “The book treats Sarkozy as an emblem of a particular kind of reactionary politics, and identifies him with an attempt to kill off that which is officially already dead: the emancipatory project that, defiantly, Badiou still calls communism. Badiou claims that Sarkozy’s rise is the return of a kind of ‘Pétainist’ mass subjectivity first instigated by the Vichy regime’s collaboration with the Nazis in World War II; the enemy that is being acquiesced to now, though, is of course capital.”[30] |

公的論争 反ユダヤ主義への非難と反論 2005年、バディウの『Circonstances 3: Portées du mot 'juif'』(「ユダヤ人」という言葉の用法)の出版後、パリの知的生活において激しい論争が勃発した[24]。この本は強い反響を呼び、この論争はフ ランスの新聞『ル・モンド』や文化雑誌『レ・タン・モダン』で記事が行き交うほどの大騒動となった。国際哲学コレージュの元会長である言語学者でラカン派 の哲学者ジャン=クロード・ミルナーは、バディウを反ユダヤ主義者として非難した[25]。 バディウはこの告発に力強く反論し、彼の告発者たちはしばしば国民国家と宗教的嗜好を混同し、この傾向に異議を唱える者に反ユダヤ主義者のレッテルを貼る と宣言した: 「絶滅の事実から、「ユダヤ人 」という述語とその宗教的・共同体主義的次元について、それが何か特別な価値化、つまり超越的な告知を受けるという結論に至らないというただそれだけの理 由で、誰からも反ユダヤ主義だと非難されるのは、まったく耐え難いことである!- また、植民地的な性質が明白であり、ありふれたものであるイスラエルの搾取を特別に容認することもない。私は、この種の政治的恐喝を、公的にも私的にも、 もはや誰も受け入れないことを提案する」[26]。 バディウはイスラエルという国家を「すべての国家よりも不純であるわけでも、不純でないわけでもない」としながらも、「ユダヤ人国家であるというその排他 的なアイデンティティ主義的主張と、この主張から絶え間ない特権を引き出すやり方、特に国際法として我々に役立つものを足元から踏みにじることになると き」に異議を唱えている。例えば、彼はこう続ける。「イスラム国家は、『アラブ国家』のさまざまなバージョンがそうであったように、モデルとしては確かに 進歩的ではない。タリバンがアフガニスタンの近代化の道を体現していないという点では、誰もが同意しているようだ」[26]。近代的な民主主義国家は、す べての住民を市民として数えなければならない。イスラエルがこの地域で唯一の「民主的」国家であると主張されることがある。しかし、この国家が自らをユダ ヤ人国家として提示しているという事実は、真っ向から矛盾している」[26]。 バディウは、現在進行中の政治的問題は、共同体主義的な宗教的次元を強調しないことで解決できると楽観的である: パレスチナ人』や『アラブ人』という記号は、『ユダヤ人』という記号に許される以上に美化されるべきではない。その結果、中東紛争の正当な解決策は、2つ の有刺鉄線国家という恐ろしい制度ではない。その解決策とは、世俗的で民主的なパレスチナの創設である......それは、政治的な見地から、また慣習の 非政治的な連続性に関係なく、「アラブ人でもユダヤ人でもない」場所をこれらの土地に作ることが完全に可能であることを示すものである。これは間違いな く、地域のマンデラを要求するだろう」[26]。 サルコジのパンフレット アラン・バディウは2007年、『サルコジの意味』(De quoi Sarkozy est-il le nom?)という小冊子で一躍有名になり、瞬く間に6万部を売り上げた。 ラファエル・バールが当時(2009年)指摘していたように、バディウはサルコジを軽蔑しており、彼の名前をほとんど書くことができなかった。しかし、バールが指摘するように、この論争は反ユダヤ主義を超え、フランス人であることの意味の核心を突いていた: 「バディウはサルコジを、フランス政治における道徳的な臆病さの体現者と見ている。バディウにとって、サルコジは「超越的なペスタン主義」の象徴である。 マーク・フィッシャーはバディウの努力に感銘を受けた: 「本書はサルコジをある種の反動的な政治の象徴として扱い、公式にはすでに死んでいるもの、つまりバディウが反抗的に共産主義と呼んでいる解放プロジェク トを抹殺しようとする試みと同一視している。バディウは、サルコジの台頭は、第二次世界大戦におけるヴィシー政権のナチスとの協力によって最初に扇動され た、ある種の「ペテイニスト」的な大衆主観性の復活であると主張している。 |

| Works https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Alain_Badiou#Works |

業績は、下記にリンクしてください、ここでは省略https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Alain_Badiou#Works |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Alain_Badiou |

|

| Speculative realism Speculative realism is a movement in contemporary Continental-inspired philosophy (also known as post-Continental philosophy)[1] that defines itself loosely in its stance of metaphysical realism against its interpretation of the dominant forms of post-Kantian philosophy (or what it terms "correlationism").[2] Speculative realism takes its name from a conference held at Goldsmiths College, University of London in April 2007.[3] The conference was moderated by Alberto Toscano of Goldsmiths College, and featured presentations by Ray Brassier of American University of Beirut (then at Middlesex University), Iain Hamilton Grant of the University of the West of England, Graham Harman of the American University in Cairo, and Quentin Meillassoux of the École Normale Supérieure in Paris. Credit for the name "speculative realism" is generally ascribed to Brassier,[4] though Meillassoux had already used the term "speculative materialism" to describe his own position.[4] A second conference, entitled "Speculative Realism/Speculative Materialism", took place at the UWE Bristol on Friday 24 April 2009, two years after the original event at Goldsmiths.[5] The line-up consisted of Ray Brassier, Iain Hamilton Grant, Graham Harman, and (in place of Meillassoux, who was unable to attend) Alberto Toscano.[5] A third conference, entitled "Object Oriented Ontology: A Symposium", was held at Georgia Institute of Technology's School of Literature, Communication and Culture (now the School of Literature, Media, and Communication) on April 23, 2010.[6] This symposium was hosted by Ian Bogost and included Levi Bryant, Graham Harmon, Steven Shaviro, Hugh Crawford, Carl DiSalvo, John Johnston, Barbara Maria Stafford, and Eugene Thacker. |

スペキュラティヴ・リアリズム、ないしは思弁的リアリズム 思弁的実在論とは、現代の大陸哲学(ポスト大陸哲学としても知られている)[1]における運動であり、ポスト・カント哲学の支配的な形態(あるいは「相関主義」と呼ばれるもの)の解釈に対して、形而上学的実在論のスタンスで緩やかに定義している[2]。 思弁的実在論は、2007年4月にロンドン大学ゴールドスミスカレッジで開催された会議に由来する[3]。この会議はゴールドスミスカレッジのアルベル ト・トスカーノによって司会され、ベイルート・アメリカン大学(当時はミドルセックス大学)のレイ・ブラシエ、西イングランド大学のイアン・ハミルトン・ グラント、カイロ・アメリカン大学のグレアム・ハーマン、パリの高等師範学校のクエンティン・メイヤスーがプレゼンテーションを行った。思弁的実在論」と いう名称は一般的にブラシエの功績とされているが[4]、メイヤスーは自身の立場を説明するために「思弁的唯物論」という用語をすでに使用していた [4]。 スペキュラティヴ・リアリズム/スペキュラティヴ・マテリアリズム」と題された2回目のカンファレンスは、ゴールドスミスでのオリジナルのイベントから2 年後の2009年4月24日金曜日にUWEブリストルで開催された[5]。ラインナップはレイ・ブラシエ、イアン・ハミルトン・グラント、グレアム・ハー マン、そして(出席できなかったメイヤスーの代わりに)アルベルト・トスカーノで構成されていた[5]。 オブジェクト指向オントロジー: このシンポジウムはイアン・ボゴストが主催し、レヴィ・ブライアント、グレアム・ハーモン、スティーヴン・シャヴィロ、ヒュー・クロフォード、カール・ ディサルヴォ、ジョン・ジョンストン、バーバラ・マリア・スタッフォード、ユージン・サッカーが参加した。 |

| Critique of correlationism While often in disagreement over basic philosophical issues, the speculative realist thinkers have a shared resistance to what they interpret as philosophies of human finitude inspired by the tradition of Immanuel Kant. What unites the four core members of the movement is an attempt to overcome both "correlationism"[7] and "philosophies of access". In After Finitude, Meillassoux defines correlationism as "the idea according to which we only ever have access to the correlation between thinking and being, and never to either term considered apart from the other."[8] Philosophies of access are any of those philosophies which privilege the human being over other entities. For speculative realists, both ideas represent forms of anthropocentrism. All four of the core thinkers within speculative realism work to overturn these forms of philosophy which privilege the human being, favouring distinct forms of realism against the dominant forms of idealism in much of contemporary Continental philosophy. |

相関主義批判 基本的な哲学的問題をめぐって意見が対立することはしばしばあるが、思弁的リアリズムの思想家たちは、イマヌエル・カントの伝統に触発された人間の有限性の哲学と解釈するものへの抵抗を共有している。 この運動の4人の中心的メンバーを結びつけているのは、「相関主義」[7]と「アクセスの哲学」の両方を克服しようとする試みである。メイヤスーは 『After Finitude』の中で、相関主義を「思考と存在の相関関係にのみアクセスすることができ、他方から切り離されて考えられるどちらの用語にもアクセスす ることはできないという考え方」[8]と定義している。思弁的実在論者にとっては、どちらの考え方も人間中心主義の一形態である。 思弁的実在論の中核をなす4人の思想家はいずれも、人間を優遇するこうした哲学の形式を覆すべく活動しており、現代大陸哲学の多くで支配的な観念論の形式に対して、明確な実在論の形式を支持している。 |

| Variations While sharing in the goal of overturning the dominant strands of post-Kantian thought in Continental philosophy, there are important differences separating the core members of the speculative realist movement and their followers. Speculative materialism In his critique of correlationism, Quentin Meillassoux (who uses the term speculative materialism to describe his position)[4] finds two principles as the focus of Kant's philosophy. The first is the principle of correlation itself, which claims essentially that we can only know the correlate of Thought and Being; what lies outside that correlate is unknowable. The second is termed by Meillassoux the principle of factiality, which states that things could be otherwise than what they are. This principle is upheld by Kant in his defence of the thing-in-itself as unknowable but imaginable. We can imagine reality as being fundamentally different even if we never know such a reality. According to Meillassoux, the defence of both principles leads to "weak" correlationism (such as those of Kant and Husserl), while the rejection of the thing-in-itself leads to the "strong" correlationism of thinkers such as late Ludwig Wittgenstein[9] and late Martin Heidegger, for whom it makes no sense to suppose that there is anything outside of the correlate of Thought and Being,[citation needed] and so the principle of factiality is eliminated in favour of a strengthened principle of correlation. Meillassoux follows the opposite tactic in rejecting the principle of correlation for the sake of a bolstered principle of factiality in his post-Kantian return to Hume. By arguing in favour of such a principle, Meillassoux is led to reject the necessity not only of all physical laws of nature, but all logical laws except the Principle of Non-Contradiction (since eliminating this would undermine the Principle of Factiality which claims that things can always be otherwise than what they are). By rejecting the Principle of Sufficient Reason, there can be no justification for the necessity of physical laws, meaning that while the universe may be ordered in such and such a way, there is no reason it could not be otherwise. Meillassoux rejects the Kantian a priori in favour of a Humean a priori, claiming that the lesson to be learned from Hume on the subject of causality is that "the same cause may actually bring about 'a hundred different events' (and even many more)."[10] The primary foundation from which Meillassoux extends the rest of his theory by arguing for a principle: the necessity of contingency itself. That is, the only thing objectively necessary is that no thing/object is necessary to every subject. Thus, all things are contingent. Using this as an objective position, he proceeds to redevelop a metaphysics for science and technology which recovers what he calls ancestral events: materially real events which occur outside of phenomenological subjectivity. He claims that without the objectivity of contingency, a philosopher of metaphysics should reject that such events like the Big Bang are legitimate. Although, some have argued that the problem is not that these ancestral events are outside of human notions of time, since many such examples of these events in fact do have materially sensible data which places them in terms of human interpretations of time, but rather it applies more strongly to real things which are not empirically observable:[11] e.g. quarks or genetic information. While not committed entirely to speculative materialism, Yuk Hui references and uses an analogous line of reasoning in Recursivity and Contingency[12] in his development of cosmotechnics, and actively works within similar philosophical lineages. Object-oriented ontology The central tenet of Graham Harman and Levi Bryant's object-oriented ontology (OOO) is that objects have been neglected in philosophy in favor of a "radical philosophy" that tries to "undermine" objects by saying that objects are the crusts to a deeper underlying reality, either in the form of monism or a perpetual flux, or those that try to "overmine" objects by saying that the idea of a whole object is a form of folk ontology. According to Harman, everything is an object, whether it be a mailbox, electromagnetic radiation, curved spacetime, the Commonwealth of Nations, or a propositional attitude; all things, whether physical or fictional, are equally objects. Sympathetic to panpsychism, Harman proposes a new philosophical discipline called "speculative psychology" dedicated to investigating the "cosmic layers of psyche" and "ferreting out the specific psychic reality of earthworms, dust, armies, chalk, and stone".[13] Harman defends a version of the Aristotelian notion of substance. Unlike Leibniz, for whom there were both substances and aggregates, Harman maintains that when objects combine, they create new objects. In this way, he defends an a priori metaphysics that claims that reality is made up only of objects and that there is no "bottom" to the series of objects. For Harman, an object is in itself an infinite recess, unknowable and inaccessible by any other thing. This leads to his account of what he terms "vicarious causality". Inspired by the occasionalists of medieval Islamic philosophy, Harman maintains that no two objects can ever interact save through the mediation of a "sensual vicar".[14] There are two types of objects, then, for Harman: real objects and the sensual objects that allow for interaction. The former are the things of everyday life, while the latter are the caricatures that mediate interaction. For example, when fire burns cotton, Harman argues that the fire does not touch the essence of that cotton which is inexhaustible by any relation, but that the interaction is mediated by a caricature of the cotton which causes it to burn. Transcendental materialism Iain Hamilton Grant defends a position he calls transcendental materialism.[15] He argues against what he terms "somatism", the philosophy and physics of bodies. In his Philosophies of Nature After Schelling, Grant tells a new history of philosophy from Plato onward based on the definition of matter. Aristotle distinguished between Form and Matter in such a way that Matter was invisible to philosophy, whereas Grant argues for a return to the Platonic Matter as not only the basic building blocks of reality, but the forces and powers that govern our reality. He traces this same argument to the post-Kantian German idealists Johann Gottlieb Fichte and Friedrich Wilhelm Joseph Schelling, claiming that the distinction between Matter as substantive versus useful fiction persists to this day and that we should end our attempts to overturn Plato and instead attempt to overturn Kant and return to "speculative physics" in the Platonic tradition, that is, not a physics of bodies, but a "physics of the All".[16] Eugene Thacker has examined how the concept of "life itself" is both determined within regional philosophy and also how "life itself" comes to acquire metaphysical properties. His book After Life shows how the ontology of life operates by way of a split between "Life" and "the living," making possible a "metaphysical displacement" in which life is thought via another metaphysical term, such as time, form, or spirit: "Every ontology of life thinks of life in terms of something-other-than-life...that something-other-than-life is most often a metaphysical concept, such as time and temporality, form and causality, or spirit and immanence"[17] Thacker traces this theme from Aristotle, to Scholasticism and mysticism/negative theology, to Spinoza and Kant, showing how this three-fold displacement is also alive in philosophy today (life as time in process philosophy and Deleuzianism, life as form in biopolitical thought, life as spirit in post-secular philosophies of religion). Thacker examines the relation of speculative realism to the ontology of life, arguing for a "vitalist correlation": "Let us say that a vitalist correlation is one that fails to conserve the correlationist dual necessity of the separation and inseparability of thought and object, self and world, and which does so based on some ontologized notion of 'life'.''.[18] Ultimately Thacker argues for a skepticism regarding "life": "Life is not only a problem of philosophy, but a problem for philosophy."[17] Other thinkers have emerged within this group, united in their allegiance to what has been known as "process philosophy", rallying around such thinkers as Schelling, Bergson, Whitehead, and Deleuze, among others. A recent example is found in Steven Shaviro's book Without Criteria: Kant, Whitehead, Deleuze, and Aesthetics, which argues for a process-based approach that entails panpsychism as much as it does vitalism or animism. For Shaviro, it is Whitehead's philosophy of prehensions and nexus that offers the best combination of continental and analytical philosophy. Another recent example is found in Jane Bennett's book Vibrant Matter,[19] which argues for a shift from human relations to things, to a "vibrant matter" that cuts across the living and non-living, human bodies and non-human bodies. Leon Niemoczynski, in his book Charles Sanders Peirce and a Religious Metaphysics of Nature, invokes what he calls "speculative naturalism" so as to argue that nature can afford lines of insight into its own infinitely productive "vibrant" ground, which he identifies as natura naturans. Transcendental nihilism In Nihil Unbound: Enlightenment and Extinction, Ray Brassier defends what Michael Austin, Paul Ennis, Fabio Gironi term as transcendental nihilism.[20] He maintains that philosophy has avoided the traumatic idea of extinction, instead attempting to find meaning in a world conditioned by the very idea of its own annihilation. Thus Brassier critiques both the phenomenological and hermeneutic strands of continental philosophy as well as the vitality of thinkers like Gilles Deleuze, who work to ingrain meaning in the world and stave off the "threat" of nihilism. Instead, drawing on thinkers such as Alain Badiou, François Laruelle, Paul Churchland and Thomas Metzinger, Brassier defends a view of the world as inherently devoid of meaning. That is, rather than avoiding nihilism, Brassier embraces it as the truth of reality. Brassier concludes from his readings of Badiou and Laruelle that the universe is founded on the nothing,[21] but also that philosophy is the "organon of extinction," that it is only because life is conditioned by its own extinction that there is thought at all.[22] Brassier then defends a radically anti-correlationist philosophy proposing that Thought is conjoined not with Being, but with Non-Being. |

相違点 大陸哲学におけるポスト・カント派思想の支配的な流れを覆すという目標を共有しながらも、思弁的実在論運動の中心メンバーとその支持者たちとの間には重要な違いがある。 思弁的唯物論 相関主義に対する批判において、クエンティン・メイヤスー(彼は自身の立場を表現するのに思弁的唯物論という言葉を用いている)[4]は、カント哲学の焦 点として2つの原理を見出している。ひとつは相関の原理そのものであり、これは本質的に「思考」と「存在」の相関関係のみを知ることができ、その相関関係 の外側にあるものは知ることができないという主張である。第二は、メイヤスーによって「事実性の原理」と呼ばれるもので、物事はそれ以外のものである可能 性があるとするものである。この原理は、カントが「物自体」を「知ることはできないが想像することはできる」と擁護する際に支持されている。私たちは、た とえそのような現実を知ることがなくても、現実が根本的に異なっていると想像することができる。Meillassouxによれば、両原則の擁護は(カント やフッサールのような)「弱い」相関主義につながり、一方、物我の否定は後期ルートヴィヒ・ウィトゲンシュタイン[9]や後期マルティン・ハイデガーのよ うな「強い」相関主義につながる。 メイヤスーはカント以後のヒュームへの回帰において、事実性の原理を強化するために相関性の原理を否定するという逆の戦術をとっている。このような原理を 支持することで、メイヤスーは、すべての物理的自然法則の必然性だけでなく、非矛盾性の原理を除くすべての論理的法則の必然性も否定することになる(これ を排除すると、物事は常にありのままである以外にあり得ないと主張する事実性の原理が損なわれるからである)。十分理由の原理を否定することで、物理法則 の必然性を正当化することができなくなる。つまり、宇宙はこのような秩序であるかもしれないが、そうでなければありえないという理由はないということであ る。メイヤスーはカント的アプリオリを否定し、ヒューム的アプリオリを支持している。ヒュームから学ぶべき因果関係の教訓は、「同じ原因が実際には『百の 異なる出来事』(さらにはそれ以上)をもたらすかもしれない」ということであると主張している[10]。 メイヤスーは、偶発性そのものの必然性という原理を主張することによって、そこから自説の残りの部分を拡張している。つまり、客観的に必要な唯一のこと は、どのような事物/対象もすべての主体にとって必要ではないということである。したがって、すべての物事は偶発的である。これを客観的な立場として、彼 は科学と技術のための形而上学を再開発し、彼が祖先的出来事と呼ぶもの、つまり現象学的主観性の外側で起こる物質的に実在する出来事を回復していく。彼 は、偶発性の客観性なしには、形而上学の哲学者はビッグバンのような事象が正当であることを否定すべきだと主張する。というのも、このような事象の多くの 例には、それらを人間の時間解釈の観点から位置づける物質的に知覚可能なデータが実際に存在するからである。投機的唯物論に完全に傾倒しているわけではな いが、ユック・ホイは『再帰性と偶発性』[12]において、類似した推論を参照し、宇宙工学の発展に用いており、同様の哲学的系譜の中で積極的に活動して いる。 オブジェクト指向の存在論 グレアム・ハーマンとレヴィ・ブライアントのオブジェクト指向存在論(OOO)の中心的な考え方は、オブジェクトは一元論や永続的な流転という形で、より 深い根底にある現実への皮膜であると言ってオブジェクトを「弱体化」させようとする「急進的な哲学」や、オブジェクト全体という考え方はフォーク存在論の 一形態であると言ってオブジェクトを「過剰化」させようとする哲学のために、オブジェクトが哲学において軽視されてきたというものである。ハーマンによれ ば、郵便受けであれ、電磁波であれ、曲がった時空であれ、コモンウェルス・オブ・ネイションズであれ、命題の態度であれ、すべてが物体であり、物理的なも のであれ、架空のものであれ、すべてのものは等しく物体である。汎心論に共鳴するハーマンは、「精神の宇宙層」を調査し、「ミミズ、塵、軍隊、チョーク、 石の具体的な精神的現実を探し出す」ことに特化した「思弁的心理学」と呼ばれる新しい哲学的学問分野を提案している[13]。 ハーマンはアリストテレス的な物質概念を擁護している。物質と集合体の両方が存在したライプニッツとは異なり、ハーマンは物体が結合すると新しい物体が生 まれると主張している。このようにして彼は、現実は物体のみから成り立ち、物体の系列に「底」はないと主張するアプリオリな形而上学を擁護する。ハーマン にとって、物体はそれ自体が無限の凹部であり、他のいかなるものからも知ることができず、アクセスすることもできない。これが彼の言う「代理的因果性」の 説明につながる。中世イスラム哲学の機会論者に触発されたハーマンは、「官能的な代理人」の仲介を経なければ、二つの対象が相互作用することはあり得ない と主張する[14]。前者は日常生活のものであり、後者は相互作用を媒介する戯画である。例えば、火が綿を燃やすとき、ハルマンは、火はいかなる関係に よっても尽きることのない綿の本質に触れているのではなく、相互作用は綿を燃やす原因となる綿の戯画によって媒介されていると主張する。 超越論的唯物論 イアン・ハミルトン・グラントは、彼が超越論的唯物論と呼ぶ立場を擁護している。シェリング以後の自然哲学』(Philosophies of Nature After Schelling)の中で、グラントは物質の定義に基づいてプラトン以降の新しい哲学史を語る。アリストテレスは形と物質を区別し、物質が哲学にとって 不可視であったのに対し、グラントはプラトン的な物質に立ち返り、現実の基本的な構成要素であるだけでなく、我々の現実を支配する力と力であると主張す る。彼はこの同じ議論をカント以後のドイツの観念論者であるヨハン・ゴットリープ・フィヒテとフリードリヒ・ヴィルヘルム・ヨーゼフ・シェリングにまで遡 り、物質が実体的なものであるか有用な虚構であるかの区別は今日まで続いており、プラトンを覆そうとする試みは終わりにして、代わりにカントを覆し、プラ トンの伝統における「思弁的な物理学」、すなわち物体の物理学ではなく「万物の物理学」に回帰することを試みるべきだと主張している[16]。 ユージン・サッカーは、「生そのもの」という概念が地域哲学の中でどのように決定され、また「生そのもの」がどのようにして形而上学的な性質を獲得するよ うになるのかを考察している。彼の著書『After Life』は、生命の存在論が「生命」と「生きているもの」との間の分裂によってどのように作用しているかを示しており、生命が時間、形態、精神といった 別の形而上学的な用語を介して思考されるという「形而上学的な置換」を可能にしている: 「生命に関するあらゆる存在論は、生命以外の何かという観点から生命を考える。 サッカーはこのテーマをアリストテレスからスコラ学、神秘主義/否定神学、スピノザ、カントへとたどり、この三重のズレが今日の哲学にも生きていることを 示す(プロセス哲学やドゥルーズ主義における時間としての生命、生政治思想における形式としての生命、ポスト世俗的宗教哲学における精神としての生命)。 サッカーは、思弁的実在論と生命の存在論との関係を考察し、「生命論的相関関係」を主張している: 「生命論的相関関係とは、思考と対象、自己と世界の分離と不可分性という相関主義的な二重の必然性を保てないものであり、「生命」という存在論化された概 念に基づいてそうするものである: 「生命は哲学の問題であるだけでなく、哲学にとっての問題である」[17]。 このグループの中には、シェリング、ベルクソン、ホワイトヘッド、ドゥルーズなどの思想家を中心に、「プロセス哲学」として知られるものへの忠誠を誓い合 う思想家も現れた。最近の例としては、スティーヴン・シャヴィロの著書『Without Criteria』が挙げられる: Kant、Whitehead、Deleuze、そしてAesthetics)では、生命論やアニミズムと同様に汎心論を伴うプロセス・ベースのアプロー チを主張している。シャヴィロにとって、大陸哲学と分析哲学の最良の組み合わせを提供するのは、ホワイトヘッドの先入観と結びつきの哲学である。また、 ジェーン・ベネットの著書『Vibrant Matter』[19]は、人間と物との関係から、生者と非生者、人間の身体と人間以外の身体を横断する「活力ある物質」への転換を主張している。 Leon Niemoczynskiは、著書『Charles Sanders Peirce and a Religious Metaphysics of Nature』(チャールズ・サンダース・パイスと自然の宗教的形而上学)の中で、彼が「思弁的自然主義」と呼ぶものを呼び起こし、自然はそれ自身の無限 に生産的な「活力ある」大地への洞察の糸口を与えることができると主張している。 超越論的ニヒリズム ニヒル・アンバウンド レイ・ブラシエは『ニヒル・アンバウンド:啓蒙と消滅』において、マイケル・オースティン、ポール・アニス、ファビオ・ジローニが超越論的ニヒリズムと呼 ぶものを擁護している[20]。このようにブラシエは、大陸哲学の現象学的・解釈学的な流れや、ジル・ドゥルーズのような、世界に意味を根付かせ、ニヒリ ズムの「脅威」を食い止めようとする思想家の活力の両方を批判している。その代わりに、アラン・バディウ、フランソワ・ラリュエル、ポール・チャーチラン ド、トマス・メッツィンガーといった思想家を引き合いに出し、ブラシエは、世界は本質的に意味を欠いているという見方を擁護する。つまり、ブラシエはニヒ リズムを避けるのではなく、現実の真実として受け入れているのである。ブラシエはバディウとラリュエルの読解から、宇宙は無の上に成立していると結論づけ る[21]と同時に、哲学は「消滅のオルガノン」であり、生命がそれ自身の消滅によって条件づけられているからこそ、思考がまったく存在するのだとも結論 づける[22]。そしてブラシエは、「思考」は「存在」ではなく「非存在」と結合していると提案する、根本的に反相関主義的な哲学を擁護する。 |

| Controversy about a "philosophical movement" In an interview with Kronos magazine published in March 2011, Ray Brassier denied that there is any such thing as a "speculative realist movement" and firmly distanced himself from those who continue to attach themselves to the brand name:[23] The "speculative realist movement" exists only in the imaginations of a group of bloggers promoting an agenda for which I have no sympathy whatsoever: actor-network theory spiced with pan-psychist metaphysics and morsels of process philosophy. I don't believe the internet is an appropriate medium for serious philosophical debate; nor do I believe it is acceptable to try to concoct a philosophical movement online by using blogs to exploit the misguided enthusiasm of impressionable graduate students. I agree with Deleuze's remark that ultimately the most basic task of philosophy is to impede stupidity, so I see little philosophical merit in a "movement" whose most signal achievement thus far is to have generated an online orgy of stupidity. Further Brassier suggests that a philosophical movement cannot believably be bound to merely anti-correlationism.[24] Despite this, many of those who discuss different approaches to escape Meillassoux's correlationist cycle, suggesting active philosophical discourse on a particular topic. Ian Bogost's work, Alien Phenomenology,[25] rethinks what OOO phenomenology would be while others argue OOO rejects phenomenology outright. Similarly, Steven Shaviro actively endorses panpsychism[26] and reaffirms his earlier endorsement of process philosophy,[27] rejecting certain aspects of Harmon's work and Brassier's criticisms about the existence of a movement. Additionally Jane Bennett's Vibrant Matter[19] also enables forms of phenomenology as she exemplifies through several chapters. In doing so, these authors suggest some form of phenomenology in speculative realism despite the rejection of correlationist philosophy. As such, one of the fundamental controversies within Speculative Realism is less agreement or disagreement about correlationism as a problem, but instead is a discussion of the feasibility or need of philosophies of phenomenology and cognition after being separated from philosophies of ontology. On this debate Harmon and Meillassoux suggest there is no need for phenomenology while Shaviro, Bennett, and Bogost suggest a separation of anti-correlation of ontology and phenomenology does not render either to be empty philosophical topics. Another controversy is how important Alfred North Whitehead's process philosophy and speculative philosophy[28] are to anti-correlationism. While Meillassoux associates anti-correlationism to "speculative materialism," he does not cite Whitehead in association in the development of After Finitude.[29] Additionally Brassier's statements above suggest he rejects the association. However, between Shaviro, Strengers, and many others, the association of Whitehead is largely consistent with anti-correlationism and thus remains a valuable inspiration. |

「哲学運動 」をめぐる論争 2011年3月に発表された『クロノス』誌とのインタビューで、レイ・ブラシエは「思弁的実在論運動」なるものが存在することを否定し、このブランド名に固執し続ける人々から固く距離を置いた[23]。 思弁的実在論運動」は、私がまったく共感できないアジェンダを推進するブロガー集団の想像の中にしか存在しない:行為者ネットワーク理論に汎心霊主義的形 而上学とプロセス哲学のもろもろのスパイスを加えたものである。また、多感な大学院生の誤った熱意を利用するためにブログを利用し、ネット上で哲学的ムー ブメントを作り上げようとすることが許されるとも思わない。ドゥルーズの「哲学の最も基本的な仕事は、究極的には愚かさを妨げることである」という言葉に 私は同意する。 さらにブラシエは、哲学的運動が単に反相関主義に縛られることはあり得ないと示唆している[24]。にもかかわらず、メイヤスーの相関主義サイクルから逃 れるためにさまざまなアプローチを論じる人々の多くは、特定のトピックに関する活発な哲学的言説を示唆している。イアン・ボゴストの著作『エイリアン現象 学』[25]は、OOO現象学が何であるかを再考する一方で、OOOが現象学を完全に否定していると主張する者もいる。同様に、Steven Shaviroは汎心論を積極的に支持し[26]、以前のプロセス哲学の支持を再確認しており[27]、Harmonの仕事のある側面と運動の存在に関す るBrassierの批判を拒絶している。さらにジェーン・ベネットの『Vibrant Matter』[19]も、いくつかの章を通して彼女が例証しているように、現象学の形態を可能にしている。そうすることで、これらの著者は相関主義哲学 の否定にもかかわらず、思弁的実在論における現象学のある形態を示唆している。 このように、思弁的実在論における基本的な論争の一つは、問題としての相関主義についての同意や不同意というよりも、存在論の哲学から切り離された後の現 象学や認識の哲学の実現可能性や必要性についての議論である。この議論では、ハーモンとメイヤスーが現象学の必要性はないとする一方、シャヴィロ、ベネッ ト、ボゴストは、存在論と現象学の反相関の分離は、どちらも空虚な哲学的テーマとはならないとする。 もう一つの論争は、アルフレッド・ノース・ホワイトヘッドのプロセス哲学と思弁哲学[28]が反相関主義にとってどれほど重要かということである。 Meillassouxは反相関主義を「思弁的唯物論」と関連付けているが、『After Finitude』の展開においてホワイトヘッドを関連付けて引用していない。しかし、シャヴィロ、ストリンガー、その他多くの人々の間では、ホワイト ヘッドの関連付けは反相関主義とほぼ一致しており、したがって貴重なインスピレーションであり続けている。 |

| Publications Speculative realism has close ties to the journal Collapse, which published the proceedings of the inaugural conference at Goldsmiths and has featured numerous other articles by 'Speculative Realist' thinkers; as has the academic journal Pli, which is edited and produced by members of the Graduate School of the Department of Philosophy at the University of Warwick. The journal Speculations, founded in 2010 published by Punctum Books, regularly features articles related to Speculative Realism. Edinburgh University Press publishes a book series called Speculative Realism. In 2013, Anarchist Developments in Cultural Studies journal published a special issue on the topic in relation to anarchism.[30] Between 2019 and 2021, the De Gruyter Open Access journal, Open Philosophy, published three special issues on object-oriented ontology and its critics.[31] Internet presence Speculative realism is notable for its fast expansion via the Internet in the form of blogs.[32] Websites have formed as resources for essays, lectures, and planned future books by those within the speculative realist movement. Many other blogs, as well as podcasts, have emerged with original material on speculative realism or expanding on its themes and ideas. |

出版物 スペキュラティヴ・リアリズムは、ゴールドスミスで開催された創設会議のプロシーディングスを掲載し、「スペキュラティヴ・リアリズム」思想家による多数 の記事を掲載している学術誌『Collapse』と密接な関係がある。2010年に創刊されたPunctum Books発行の学術誌『Speculations』は、投機的実在論に関連する記事を定期的に掲載している。エジンバラ大学出版局は、「投機的リアリズ ム」という書籍シリーズを出版している。 2013年には『Anarchist Developments in Cultural Studies』誌がアナーキズムとの関連で特集号を発行した[30]。 2019年から2021年にかけて、デ・グリュイターのオープンアクセスジャーナルであるOpen Philosophy誌は、オブジェクト指向存在論とその批評家に関する3つの特集号を出版した[31]。 インターネットでの存在 投機的実在論は、ブログという形でインターネットを通じて急速に拡大していることで注目されている[32]。ウェブサイトは、投機的実在論運動内の人々に よるエッセイ、講義、将来出版予定の書籍のリソースとして形成されている。他の多くのブログやポッドキャストが、投機的リアリズムに関するオリジナルな内 容や、そのテーマやアイデアを拡張する内容で登場している。 |

Kantian empiricism New realism (contemporary philosophy) Accelerationism Object-oriented ontology Objectivity Postanalytic philosophy Speculative idealism Transhumanism Transcendental empiricism Transcendental nominalism Notable speculative realists Ian Bogost Ray Brassier Levi Bryant Manuel DeLanda Tristan Garcia Iain Hamilton Grant Graham Harman Adrian Johnston Katerina Kolozova Nick Land Quentin Meillassoux Reza Negarestani Steven Shaviro Nick Srnicek Isabelle Stengers Eugene Thacker See also New materialisms |

カント経験論 新実在論(現代哲学) 加速度論 目的論的存在論 目的論 ポスト分析哲学 思弁的観念論 超人間主義 超越論的経験論 超越論的名辞論 著名な思弁的実在論者 イアン・ボゴスト レイ・ブラシエ レヴィ・ブライアント マニュエル・デランダ トリスタン・ガルシア イアン・ハミルトン・グラント グレアム・ハーマン エイドリアン・ジョンストン カテリーナ・コロゾワ ニック・ランド カンタン・メイヤスー レザ・ネガレスタニ スティーブン・シャビロ ニック・スルニチェク イザベル・ステンガーズ ユージン・サッカー 関連記事 新物質論 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Speculative_realism |

|

| Universalism is the philosophical and theological concept that some ideas have universal application or applicability. A belief in one fundamental truth is another important tenet in universalism. The living truth is seen as more far-reaching than the national, cultural, or religious boundaries or interpretations of that one truth. A community that calls itself universalist may emphasize the universal principles of most religions, and accept others in an inclusive manner. In the modern context, Universalism can also mean the Western pursuit of unification of all human beings across geographic and other boundaries under Western values, or the application of really universal or universalist constructs, such as human rights or international law.[1][2] Universalism has had an influence on modern-day Hinduism, in turn influencing modern Western spirituality.[3] Christian universalism refers to the idea that every human will eventually receive salvation in a religious or spiritual sense, a concept also referred to as universal reconciliation.[4] |

普遍主義とは、ある考え方は普遍的な適用や応用が可能であるという哲学的・神学的な概念である。 一つの基本的な真理を信じることも普遍主義の重要な信条である。生きている真理は、その一つの真理の国家的、文化的、宗教的境界や解釈よりも広範囲に及ぶ と見なされる。普遍主義を自称する共同体は、ほとんどの宗教の普遍的原則を強調し、他の宗教を包括的に受け入れることがある。 現代的な文脈では、普遍主義は西洋的な価値観の下で、地理的な境界やその他の境界を越えて全人類を統一しようとする西洋的な追求や、人権や国際法などの真に普遍的または普遍主義的な構成の適用を意味することもある[1][2]。 普遍主義は現代のヒンドゥー教に影響を与え、ひいては現代の西洋の精神性に影響を与えている[3]。 キリスト教的普遍主義とは、すべての人間が最終的に宗教的または精神的な意味での救済を受けるという考え方を指し、普遍的和解とも呼ばれる概念である[4]。 |

| Philosophy Universality Main article: Universality (philosophy) In philosophy, universality is the notion that universal facts can be discovered and is therefore understood as being in opposition to relativism and nominalism.[5] Moral universalism Main articles: Moral universalism and Moral particularism Moral universalism (also called moral objectivism or universal morality) is the meta-ethical position that some system of ethics applies universally. That system is inclusive of all individuals,[6] regardless of culture, race, sex, religion, nationality, sexual orientation, or any other distinguishing feature.[7] Moral universalism is opposed to moral nihilism and moral relativism. However, not all forms of moral universalism are absolutist, nor do they necessarily value monism. Many forms of universalism, such as utilitarianism, are non-absolutist. Other forms such as those theorized by Isaiah Berlin, may value pluralist ideals. |

哲学 普遍性 主な記事 普遍性(哲学) 哲学において普遍性とは、普遍的な事実が発見できるという考え方であり、それゆえ相対主義や名辞主義に対立するものとして理解されている[5]。 道徳的普遍主義 主な記事 道徳的普遍主義、道徳的特殊主義 道徳的普遍主義(道徳的客観主義または普遍道徳とも呼ばれる)とは、ある倫理体系が普遍的に適用されるというメタ倫理的立場である。そのシステムは、文 化、人種、性別、宗教、国籍、性的指向、または他の区別する特徴に関係なく、すべての個人を包含する[6]。しかし、すべての形態の道徳的普遍主義が絶対 主義であるわけではなく、必ずしも一元論を重視するわけでもない。功利主義のような普遍主義の多くの形態は非絶対主義である。アイザイア・バーリンが理論 化したような他の形態は、多元主義的な理想を重視することもある。 |