シェリー・タークルの処方箋は本当の解決策になるのか?

Is Sherry Turkle's prescription a

real solution?

シェリー・タークルの処方箋は本当の解決策になるのか?

Is Sherry Turkle's prescription a

real solution?

"I tweet, therefore I am, you share, therefore you are (thou art)."——私はツイートする、それゆえに我あり、君たち はシェアする、それゆ えに君あり

このページは、一連のシェリー・ タークル(Sherry Turkle, 1948- )の諸命題を 検討する。

コンピュータに知性が あるかどうかよりも、当事者にとってその知性 がどのように知覚されるかが重要だというのが、シェリー・タークル[Sherry Turkle, 1948- ]の議論(一部)だが、SNSの普及は逆にユーザーのナルシズム化と、「新しい孤独」(→「つながっていても孤独」感覚)を産むことになる。インターネッ トやSNSの普及はそれを加速化させているのが、彼女の主張である。これはスマホなくては暮らせない日本の青年に対しても、重要な問題提起でもある。

これに対する彼女の処方箋は、きわめて明確である。 スマホの電源を落として、ガチのヒューマンコミュニケーションを復権しようというもの である。

タークルの議論のやり方は、ハーバードの心理学者ら しく、社会問題を極めて単純に命題化して、かつ、その処方箋もシンプルである。しかし、これは、日常生活におけるデジタル・ネイティブたちの観察とインタ ビューを旨にする社会学者や人類学者にとっては、とても不満の残るものである。なぜなら、彼らは、インターネットやSNSを自分のナルシズム化を促進させ かつ「新しい孤独」を産むと同時に、そのメディアと利用して、人との人のあいだのリアルな出会いにも利用している。仮に、それが、古典的なハイパーメディ ア以前のノンデジタル・ネイティブにとって、いかに異様に見えようとも……。

●ジーン・トゥエンジ(2017)の孤独増加モデル (→iGen (i-Generation, internet-Generation))

● デジタル・ネイティブの定義をめぐって

"The term digital native describes a person who has grown up in the information age, (rather than having acquired familiarity with digital systems as an adult, as a digital immigrant). Digital natives was meant to describe young people born in close contact with computers and the internet through mobile phones, tablets, and video games consoles.[1: Prensky, Marc (September 2001). "Digital Natives, Digital Immigrants Part 1". On the Horizon. 9 (5): 1–6.] The formula was used to distinguish them from “digital immigrants,” that is from people who were born before the advent of the internet and came of age in a world dominated by print and television.[2] Both terms were used as early as 1996 as part of the Declaration of the Independence of Cyberspace.[3] They are often used to describe the digital gap in terms of the ability of technological use among people born from 1980 onward and those born before.[4]"- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Digital_native

「デジタルネイティブとは、情報化時代に発展してき

た人(デジタル移民のように大人になってからデジタルシステムに慣れ親しんだのではなく)を指す言葉である。デジタルネイティブは、携帯電話やタブレット

端末、ゲーム機などを通じて、コンピュータやインターネットに身近に接して生まれた若者を指す[1: Prensky, Marc

(September 2001). "Digital Natives, Digital Immigrants Part 1". On the

Horizon. 9 (5): 1-6.]

この公式は、「デジタル移民」、つまりインターネットの出現以前に生まれ、印刷物とテレビが支配する世界で成人した人々と区別するために使われた[2]。

両語は、1996年には早くも「サイバースペース独立宣言」の一部として使われた[3]。

1980年以降に生まれた人々とそれ以前に生まれた人々の技術使用能力という意味でデジタルギャップを表現するのによく使われる言葉である。」

マーク・プレンスキーのこの「民族」 と「移民」の比 喩はそれほど頭の賢いものとは言えない。なぜなら、私たちはデジタル・イミグラント(digital immigrant)の世代に相当するが、現在のデジタル利用環境状況は、私たちの先達から デジタルネイティブにいたる技術者と製作者とユーザーの相互作用による帝国世界の構築であり、別に私たちは周辺地域から帝国に移民してきたわけでない。も ちろん、帝国作りには協力はしてきたが、それは働き蟻のような貢献で、だれが女王であり、だれが兵隊蟻であると類比させることも、できないことはないが奇 矯ではある。

John Perry Barlow, "A Declaration of the Independence of Cyberspace," 1996.; "Governments of the Industrial World, you weary giants of flesh and steel, I come from Cyberspace, the new home of Mind. On behalf of the future, I ask you of the past to leave us alone. You are not welcome among us. You have no sovereignty where we gather."

「1996年2月にインターネット上の猥褻情報を規 制する Communications Decency Act(CDA, 通称・通信品位法)が米議会で可決されると、ジョン・ペリー・バーロウ(John Perry Barlow, 1947-2018)はスイス・ダボスにて A Declaration of the Independence of Cyberspace(サイバースペース独立宣言)を発表し、法案成立に抗議を行」う。

2020年の現在は、バーロウの能天気さは、

1990年代のテクノユートピアの間抜けさ加減の好例としてよくあげられるらしい(→デジ

タル・ネイティブ)。

● デジタル・イミグラント(digital immigrant)の定義

"A digital immigrant is a term used to refer to a person who was raised prior to the digital age. These individuals, often in the Generation-X/Xennial generations and older, did not grow up with ubiquitous computing or the internet, and so have had to adapt to the new language and practice of digital technologies. This can be contrasted with digital natives who know no other world than one defined by the internet and smart devices./ A digital immigrant is a person who grew up before the internet and other digital computing devices were ubiquitous - and so have had to adapt and learn these technologies./ Generally those born before the year 1985 (those before the Millennial generation) are considered to be digital immigrants./ Those born after 1985 are digital natives, having grown up only in a world defined by the internet and smart devices." (Mark Prensky 2001. Digital Natives, Digital Immigrants. From On the Horizon (MCB University Press, Vol. 9 No. 5, October 2001))

「デジタル移民とは、デジタル時代より前に育った人

を指す言葉として使われる。これらの人々は、Generation-X/Xennial世代以上であることが多く、ユビキタスコンピューティングやイン

ターネットと共に発展してこなかったため、デジタル技術の新しい言語と慣習に適応しなければなりませんでした。デジタル移民とは、インターネットやその他

のデジタルコンピューティングデバイスが普及する前に育った人たちのことで、これらの技術に適応し、学ぶ必要がありました/一般的に、1985年以前に生

まれた人たち(ミレニアル世代以前)はデジタル移民とみなされます/1985年以降に生まれた人はデジタルネイティブで、インターネットとスマートデバイ

スによって定義された世界でのみ成長しています」。

● 問題の立て方の戦略——参照:ポール・シルビア(Paul J. Silvia, 1976- )先生 (2016:94-104)

● ナルシシズムと孤独の関係

ナルシシズム(→「フロイト的ナルシシズムの理解」)

孤独(→「孤独は心理学的な概念ではない、孤独は社会学的な概念」「社会存立のための弁証法」「キュリオシティは火星の上で孤独を覚えるのか?」)

●Margaret E. Morrisの研究("Left to our own devices : outsmarting smart technology to reclaim our relationships, health, and focus") digital health. (→デジタル・ヘルス)

"Unexpected ways that individuals adapt technology to reclaim what matters to them, from working through conflict with smart lights to celebrating gender transition with selfies. We have been warned about the psychological perils of technology: distraction, difficulty empathizing, and loss of the ability (or desire) to carry on a conversation. But our devices and data are woven into our lives. We can't simply reject them. Instead, Margaret Morris argues, we need to adapt technology creatively to our needs and values. In Left to Our Own Devices, Morris offers examples of individuals applying technologies in unexpected ways-uses that go beyond those intended by developers and designers. Morris examines these kinds of personalized life hacks, chronicling the ways that people have adapted technology to strengthen social connection, enhance well-being, and affirm identity. Morris, a clinical psychologist and app creator, shows how people really use technology, drawing on interviews she has conducted as well as computer science and psychology research. She describes how a couple used smart lights to work through conflict; how a woman persuaded herself to eat healthier foods when her photographs of salads garnered "likes" on social media; how a trans woman celebrated her transition with selfies; and how, through augmented reality, a woman changed the way she saw her cancer and herself. These and the many other "off-label" adaptations described by Morris cast technology not just as a temptation that we struggle to resist but as a potential ally as we try to take care of ourselves and others. The stories Morris tells invite us to be more intentional and creative when left to our own devices." - (Morris is a skillful storyteller. This book is a good read for today's digital health initiatives and for clinicians hoping to keep up to date in current trends in mental health technology - Psychiatric Times)「Nielsen BookData」 より

「スマートライトで紛争を解決したり、セルフィーで

性別の移行を祝ったりと、個人が自分にとって大切なものを取り戻すためにテクノロジーを活用する意外な方法を紹介します。私たちは、気が散る、共感しにく

い、会話を続ける能力(あるいは意欲)が失われるなど、テクノロジーの心理的危険性について警告を発してきました。しかし、デバイスやデータは私たちの生

活の中に織り込まれているのです。単に拒否することはできません。マーガレット・モリスは、テクノロジーを私たちのニーズや価値観に合わせて創造的に適応

させる必要があると主張しています。Left to Our Own

Devicesの中でMorrisは、開発者やデザイナーが意図した以上の、予想外の方法でテクノロジーを利用する個人の例を挙げている。Morris

は、このような個人的なライフハックを検証し、人々が社会的なつながりを強化し、幸福感を高め、アイデンティティを確認するためにテクノロジーを適応させ

る方法を記録しています。臨床心理学者でありアプリ制作者でもあるMorrisは、自身が行ったインタビューやコンピュータサイエンス、心理学の研究をも

とに、人々が実際にどのようにテクノロジーを使っているのかを紹介しています。あるカップルがスマートライトを使って対立を解決したこと、ある女性がサラ

ダの写真がソーシャルメディアで「いいね!」を獲得し、より健康的な食事をするよう自分を説得したこと、あるトランス女性がセルフィーで自分の移行を祝っ

たこと、ある女性が拡張現実を通して自分の癌と自分自身に対する見方を変化させたことなどが書かれています。モリスが語るこれらやその他多くの「適応外」

適応は、テクノロジーを単に誘惑としてではなく、自分自身や他人をケアしようとする潜在的な味方として捉えている。モリスが語るストーリーは、私たちが自

分自身のデバイスに身を任せたとき、より意図的で創造的であるようにと私たちを誘う」https://www.deepl.com/ja/translator)

●「単純接触効果(mere exposure effect)」と「メディア等式(The Media Equation)」を結びつけることを思いつく

「スマートフォン・ユーザーのナルシズム化と新しい 孤独の誕生」について考えている時に「単純接触効果(mere exposure effect)」と「メディア等式 (The Media Equation)」を結びつけることを思いつく。

"The mere-exposure effect is a psychological phenomenon by which people tend to develop a preference for things merely because they are familiar with them. In social psychology, this effect is sometimes called the familiarity principle. The effect has been demonstrated with many kinds of things, including words, Chinese characters, paintings, pictures of faces, geometric figures, and sounds. In studies of interpersonal attraction, the more often someone sees a person, the more pleasing and likeable they find that person." -#Wiki.

「単なる単純接触効果(=露出効果)とは、人は単に

その物事をよく知っているというだけで、その物事に対する好みを持つようになる傾向があるという心理現象である。社会心理学では、この効果を「親しみ原

理」と呼ぶこともある。この効果は、言葉、漢字、絵画、顔写真、幾何学図形、音など、さまざまなもので実証されている。対人魅力の研究では、ある人をよく

見るほど、その人をより好ましく、好感が持てるとされています。」

From the mere-exposure effect :"Gustav Fechner conducted the earliest known research on the effect in 1876.[2] Edward B. Titchener also documented the effect and described the "glow of warmth" felt in the presence of something familiar,[3] but his hypothesis was thrown out when results showed that the enhancement of preferences for objects did not depend on the individual's subjective impressions of how familiar the objects were. The rejection of Titchener's hypothesis spurred further research and the development of current theory./ The scholar best known for developing the mere-exposure effect is Robert Zajonc (1923-2008). Before conducting his research, he observed that exposure to a novel stimulus initially elicits a fear/avoidance response in all organisms. Each subsequent exposure to the novel stimulus causes less fear and more interest in the observing organism. After repeated exposure, the observing organism will begin to react fondly to the once novel stimulus. This observation led to the research and development of the mere-exposure effect.[citation needed]..../ In 1980, a speculative and widely debated paper entitled "Feeling and Thinking: Preferences Need No Inferences," invited in honor of his receipt of the 1979 Distinguished Scientific Contribution Award from the American Psychological Association, made the argument that affective and cognitive systems are largely independent, and that affect is more powerful and comes first. This paper precipitated a great deal of interest in affect in psychology, and was one of a number of influences that brought the study of emotion and affective processes back into the forefront of American and European psychology." #Wiki.

「エドワード・B・ティッチナーもこの効果を記録

し、身近なものの存在によって感じる「暖かさの輝き」について述べている[2]が、物に対する嗜好性の向上は、そのものがどれほど身近なものであるかとい

う個人の主観的印象に依存しないことが示されたため、彼の仮説は否定された。この仮説が否定されたことで、さらなる研究が進み、現在の理論が確立されたの

である。ザヨンクは、研究の前に、すべての生物において、新規の刺激にさらされると、最初は恐怖・回避反応が起こることを観察していた。その後、新規の刺

激にさらされるたびに、観察生物は恐怖を感じなくなり、より興味を持つようになる。そして、何度も繰り返すうちに、かつての新しい刺激に好意的な反応を示

すようになる。この観察から、単なる暴露効果の研究・開発が始まった[citation

needed].../1980年、『暴露効果』と題する推測的で広く議論されている論文が発表された。」

●メランコリー / H.テレンバッハ(Hubertus Tellenbach, 1914-1994)著 ; 木村敏訳, 改訂増補版. - 東京 : みすず書房 , 1985.(旧版は1978)

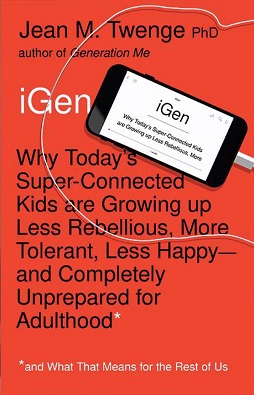

● iGen (i-Generation, internet-Generation) における心理的な性向について(サイト内リンクiGenからの引用)

| iGen:

Why Today's Super-Connected Kids Are Growing Up Less Rebellious, More

Tolerant, Less Happy—and Completely Unprepared for Adulthood—and What

That Means for the Rest of Us[a] is a 2017 nonfiction book

by Jean Twenge which studies the lifestyles, habits and values of

Americans born 1995–2012,[1] the first generation to reach adolescence

after smartphones became widespread. Twenge refers to this generation

as the "iGeneration" (also known as Generation Z). Although she argues

there are some positive trends, she expresses concern that the

generation is being isolated by technology. |

iGen: Why Today's

Super-Connected Kids Are Growing Up Less Rebellious, More Tolerant,

Less Happy and Completely Unpared for Adulthood and What That Means for

the Rest of

Us[a]はジャン・トウェンジによる2017年のノンフィクションで、1995年から2012年に生まれたアメリカ人のライフスタイル、習慣、価値観を

研究し、スマートフォン普及後初めて青年期に達した世代[1]としたものである。トゥエンジはこの世代を「iGeneration」(ジェネレーションZ

とも呼ばれる)と呼んでいる。彼女は、いくつかのポジティブな傾向があると主張する一方で、この世代がテクノロジーによって孤立していることに懸念を表明

している。 |

| In iGen, Jean Twenge examines

the advantages, disadvantages and consequences of technology in the

lives of the current generation of teens/young adults. She argues that

generational divides are more prominent than ever and parents,

educators and employers have a strong desire to understand the newer

generation. Social media and texting have replaced many face-to-face

social activities that older generations grew up with, therefore,

iGeners are spending less time interacting in person. Twenge concludes

this has led them to experience higher levels of anxiety, depression,

and loneliness than seen in prior generations. She argues that use of technology is not the only thing that distinguishes iGeners from generations prior— the way in which their time is spent contributes to changes in their behaviors and attitudes toward religion, sexuality and politics. Twenge argues that iGeners' socialization skills and wants for the future have taken a turn towards an atypical, yet safe route. She elaborates on these topics throughout different chapters of the book. Each of these changes factor into her overall argument: that iGeners are unlike any generation seen before, and earlier generations must learn to understand them in order to keep up. With their new developmental ways, their impact will be unlike any before them. Her evaluations are based on four databases: Monitoring the Future, The Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance System, The American Freshman Survey, and the General Social Survey. Each of these surveys asked iGeners quantitative and qualitative questions to determine if being raised synergistically with technology has made them less rebellious, more tolerant, less happy, less resilient to the challenge of adulthood, as Twenge asserts. In addition to the databases, Twenge conducted interviews with young adults across the country to collect first hand data about the challenges growing up with technology being presented to the current generation of teens and young adults.[2] |

Jean

Twengeは、『iGen』の中で、現在の10代/20代の若者の生活におけるテクノロジーの利点、欠点、結果について考察している。世代間の隔たりは

かつてないほど顕著であり、親や教育者、雇用主は新しい世代を理解したいと強く願っている、と彼女は主張している。旧世代が行っていた対面式の社会活動の多くがソーシャルメディアやテキストに取って代わられた

ため、iGenersは直接会って交流する時間が少なくなっている。このため、iGenersは以前の世代よりも高いレベルの不安、うつ、孤独を経験する

ようになったとTwenge氏は結論付けている。 iGenersを前の世代と区別するのはテクノロジーの使用だけではない。彼らの時間の使い方は、宗教、セクシュアリティ、政治に対する彼らの行動や態度 の変化に寄与していると、彼女は主張している。Twengeは、iGenersの社会化スキルや将来への希望が、非典型的でありながら安全な方向へ向かっ ていると論じている。彼女は、本書のさまざまな章を通じて、これらのトピックを詳しく説明している。iGenersはこれまでのどの世代とも違うので、前の世代は彼らを理解することを学ばなけれ ばならない、というのが彼女の主張である。iGenersはこれまでにない世代であり、前の世代は彼らを理解することを学ばなければついて いけない、というのが本書の主張である。 彼女の評価は、4つのデータベースに基づいている。モニタリング・ザ・フューチャー、青少年リスク行動監視システム、アメリカ新入生調査、一般社会調査の 4つのデータベースに基づいている。これらの調査はそれぞれ、iGenersに定量的・定性的な質問を投げかけ、Twengeが主張するように、テクノロ ジーと相乗的に育てられたことによって、反抗的でなくなったか、寛容でなくなったか、幸福でなくなったか、大人への挑戦に対する弾力性がなくなったかを判 断している。データベースに加えて、Twengeは全米の若年層へのインタビューを実施し、現在の10代や若年層に提示されているテクノロジーとともに成 長する課題についての直接のデータを収集した[2]。 |

| Reception Sonia Livingstone at the London School of Economics wrote that the book attracted "an avalanche of both eulogistic and critical reviews." She was cautious about Twenge's findings, noting some graphs that did not fit them and suggesting other potential factors were at play. She did agree that there had been a recent downturn of mental health among the youth and concluded: "Let's hope the questions raised here foster more and better research about and with young people growing up in the digital age."[3] Marilyn Gates gave the book a positive review in the New York Journal of Books, calling it "an important barometer of youth mental health" and "a must-read for parents, teachers, employers, and anybody trying to make sense of iGen behavior and what this bodes for the future." She described Twenge as a "highly skilled and empathetic interviewer" and also praised her writing for being easy to understand. She highlighted some flaws, such as data cherry-picked "for maximum shock value", correlation being treated as causation and that it did not entirely avoid "youth bashing".[4] Annalisa Quinn at NPR was skeptical, arguing that the book was part of the familiar trend of older generations feeling superior to younger ones ("one of our great human traditions"). She was particularly critical of how Twenge "draws her conclusions first and then collects evidence that supports those conclusions, ignoring evidence that doesn't."[5] In the United Arab Emirates newspaper The National, Steve Donoghue said it drew alarmist conclusions despite data on the contrary: "Even Twenge's own charts and numbers, read with optimism, tend to indicate that members of iGen are generally far more socially aware, far less given to prejudice, and far, far sharper than their parents."[6] |

受容と批判 ロンドン・スクール・オブ・エコノミクスのソニア・リビングストーンは、この本が「賛美と批判の両方のレビューで雪崩を打った」と書いている。彼女は Twengeの発見に対して慎重で、いくつかのグラフがそれに当てはまらないことを指摘し、他の潜在的な要因が作用していることを示唆した。彼女は、最 近、若者の間で精神的な健康状態が悪化していることには同意し、こう結論づけた。「ここで提起された疑問が、デジタル時代に成長する若者についての、そし て若者たちとのより良い研究を促進することを期待しよう」[3]。 マリリン・ゲイツは、ニューヨーク・ジャーナル・オブ・ブックスで、この本を「若者の精神衛生に関する重要なバロメーター」、「親、教師、雇用主、そして iGenの行動とそれが将来にもたらす意味を理解しようとするすべての人にとって必読書」と呼び、肯定的な評価を与えています]。彼女はTwengeを 「高度に熟練した共感できるインタビュアー」と評し、また彼女の文章がわかりやすいと賞賛しています。彼女は、「最大限の衝撃を与えるために」データが選ばれていること、相関関係が因果関係として扱われて いること、「若者バッシング」を完全に回避できていないことなど、いくつかの欠点を強調した[4]。 NPRのアナリサ・クインは懐疑的で、この本は、年上の世代が年下の世代に対して優 越感を感じるというおなじみの傾向(「人類の偉大な伝統のひとつ」)の一部であると論じた。彼女は特に、Twengeが「最初に結論を出し、その結論を支持する証拠を集め、そうでない証 拠を無視する」方法を批判した[5]。アラブ首長国連邦の新聞The Nationalでは、Steve Donoghueが、反対のデータにもかかわらず、警戒すべき結論を導き出したと述べている。"Twenge自身の図表や数字でさえ、楽観的に読むと、iGenのメンバーは一般的に彼らの親 よりもはるかに社会的な意識が高く、偏見を持つことが少なく、はるかに、はるかに鋭いことを示す傾向がある"[6]と述べている。 |

| 1. "Move Over,

Millennials: How 'iGen' Is Different From Any Other Generation". The

California State University. August 22, 2017. 2. Twenge, Jean M. (2017-08-22). IGen : why today's super-connected kids are growing up less rebellious, more tolerant, less happy-- and completely unprepared for adulthood (and what this means for the rest of us) (First Atria books hardcover ed.). New York, NY. ISBN 9781501151989. OCLC 965140529. 3. Book review: iGen: why today's super-connected kids are growing up less rebellious, more tolerant, less happy – and completely unprepared for adulthood 4. "a book review by Marilyn Gates: iGen: Why Today's Super-Connected Kids Are Growing Up Less Rebellious, More Tolerant, Less Happy—and Completely Unprepared for Adulthood—and What That Means for the Rest of Us". www.nyjournalofbooks.com. Retrieved 2018-04-23. 5. Quinn, Annalisa (September 17, 2017). "Move Over Millennials, Here Comes 'iGen'... Or Maybe Not". NPR. 6. "Book review: Jean Twenge's latest spotlights dangers of being a part of the smartphone generation". The National. Retrieved 2018-04-23. |

|

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/IGen_(book) |

https://www.deepl.com/ja/translator |

| A highly readable and

entertaining first look at how today's members of iGen-the children,

teens, and young adults born in the mid-1990s and later-are vastly

different from their Millennial predecessors, and from any other

generation, from the renowned psychologist and author of Generation Me.

With generational divides wider than ever, parents, educators, and

employers have an urgent need to understand today's rising generation

of teens and young adults. Born in the mid-1990s to the mid-2000s and

later, iGen is the first generation to spend their entire adolescence

in the age of the smartphone. With social media and texting replacing

other activities, iGen spends less time with their friends in

person-perhaps why they are experiencing unprecedented levels of

anxiety, depression, and loneliness. But technology is not the only

thing that makes iGen distinct from every generation before them; they

are also different in how they spend their time, how they behave, and

in their attitudes toward religion, sexuality, and politics. They

socialize in completely new ways, reject once sacred social taboos, and

want different things from their lives and careers. More than previous

generations, they are obsessed with safety, focused on tolerance, and

have no patience for inequality. iGen is also growing up more slowly

than previous generations: eighteen-year-olds look and act like

fifteen-year-olds used to. As this new group of young people grows into

adulthood, we all need to understand them: Friends and family need to

look out for them; businesses must figure out how to recruit them and

sell to them; colleges and universities must know how to educate and

guide them. And members of iGen also need to understand themselves as

they communicate with their elders and explain their views to their

older peers. Because where iGen goes, so goes our nation-and the world.

by "Nielsen BookData" |

本書は、1990年代半ば以降に生まれた子供、10代、20代の若者で

あるiGenが、ミレニアル世代や他のどの世代とも大きく異なることを、著名な心理学者で『ジェネレーション・ミー』の著者である著者が読みやすく、楽し

く解説する初めての書です。世代間の溝がかつてないほど広がっている今、親や教育者、雇用主は、今日の10代と20代の若者たちを理解することが急務と

なっている。1990年代半ばから2000年代半ば以降に生まれたiGenは、思春期をスマートフォンの時代で過ごした最初の世代である。ソーシャルメ

ディアやテキストが他の活動に取って代わり、iGenは友人と直接会う時間が減っている。おそらく、彼らがかつてないレベルの不安、うつ、孤独を経験して

いる理由であろう。しかし、iGenがそれ以前のすべての世代と異なるのはテクノロジーだけでは

ない。時間の使い方、行動様式、宗教、セクシュアリティ、政治に対する考え方も異なっている。彼らはまったく新しい方法で社交し、かつての神聖な社会的タ

ブーを否定し、人生やキャリアに異なるものを求めている。また、iGenは前の世代よりも成長が遅く、18歳の若者はかつての15歳の若者のような姿と振

る舞いをしている。この新しい若者たちが大人になっていく過程で、私たち全員が彼らを理解する必要がある。友人や家族は彼らに気を配り、企業は彼らを採用

し、販売する方法を考えなければならないし、大学は彼らを教育し、指導する方法を知らなければならない。そして、iGenのメンバーは、年長者とコミュニ

ケーションをとり、年上の仲間に自分の意見を説明する際に、自分自身を理解する必要がある。なぜなら、iGenの行く末は、わが国、そして世界の行く末を

左右するからなのである。 |

| Jo Cox Commission on Loneliness https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jo_Cox_Commission_on_Loneliness |

|

| The Jo Cox Commission on

Loneliness was an establishment set up by British Member of parliament

Jo Cox, in order to investigate ways to reduce loneliness in the United

Kingdom. It published its final report at the end of 2017. While only

running for just over a year, the commission led to the UK government

making a lasting commitment to loneliness relief. |

孤独に関するジョー・コックス委員会は、イギリスの孤独を減らす方法を

調査するために、イギリスの国会議員であるジョー・コックスによって設立された施設です。2017年末に最終報告書を発表した。わずか1年あまりの運営期

間でしたが、この委員会をきっかけに、英国政府は孤独の解消に永続的に取り組むことになりました。 |

| The commission was established

by Jo Cox shortly before her death in the summer of 2016. It was always

intended to be a cross-party endeavour, with the Tory MP Seema Kennedy

a leading member from the start. In January 2017 the commission was

re-launched by Kennedy and the Labour MP Rachel Reeves; the two went on

to serve as co-chairs of the commission. Working together with 13

charities, including Age UK and Action for Children, the commission

produced a report outlining ways to combat loneliness in the UK. With

Jo having planned for the commission to only run for one year, the

commission was wound up in early 2018, shortly after producing its

final report.[1][2][3][4] |

この委員会は、2016年夏に亡くなる直前のジョー・コックスによって

設立されました。当初から党派を超えた取り組みとして意図されており、トリー派のシーマ・ケネディ議員が主要メンバーとして参加していました。2017年

1月、ケネディと労働党のレイチェル・リーヴス議員によって委員会は再スタートし、2人は委員会の共同議長を務めることになりました。Age

UKやAction for

Childrenを含む13の慈善団体と協力し、委員会は英国における孤独と闘う方法をまとめた報告書を作成しました。ジョーは委員会の運営期間を1年間

だけと計画していたため、委員会は最終報告書を作成した直後の2018年初頭に解散した[1][2][3][4]。 |

| The final report was released in

December 2017 and had recommendations in three areas: National leadership, including the nomination of a lead minister. Measurement, involving developing a national indicator and annual reporting. Funding, for unspecified initiatives. The report made clear that government alone would not be able to solve the problem of loneliness, with the commission also calling for action from other public sector leaders, business leaders, community and volunteer groups and regular citizens.[3][5] [4] |

最終報告書は2017年12月に発表され、3つの領域で提言がなされま

した: 主席大臣の指名を含む、国のリーダーシップ。 測定、国家指標の開発と年次報告を含む。 資金調達、不特定多数のイニシアチブのための資金調達。 報告書は、政府だけでは孤独の問題を解決できないことを明確にし、委員会は他の公共部門のリーダー、ビジネスリーダー、コミュニティやボランティアグルー プ、一般市民の行動も求めている[3][5][4]。 |

| Jo's friend Rachel Reeves

continued to lead an all party group working on loneliness even after

the commission was wound up. As of 2020 The Jo Cox Foundation still

works on the problem of loneliness in partnership with government and

with other charities.[2][1] In January 2018, prime minister Theresa May accepted the final report's recommendations, creating a ministerial lead for loneliness, with the intention that the new role will ensure loneliness reduction remains an enduring parliamentary priority. The position is often referred to by the media as the 'Minister for Loneliness' , though it is not a separate ministerial office. Initially the role was an expansion of the remit for the Minister for Sport and Civil Society. The post was first held by Tracey Crouch, then from November 2018 to July 2019 by Mims Davies, and as of 2020 is held by Baroness Barran. In October 2018, again as a result of the final report, the UK government became the first in the world to publish a loneliness reduction strategy. The strategy included commitments for loneliness reduction activity by nine different government departments; for example to encourage "social prescribing" by front line doctors, so that they can refer patients suffering from loneliness to local group activity & befriending schemes. As of May 2020, the UK government has distributed over £20 million to various initiatives to reduce loneliness. This initiative includes funding to charities dedicated to combatting loneliness, and to loneliness reduction projects run by both tech firms and community groups.[3][6][7][8][1] |

ジョーの友人であるレイチェル・リーヴスは、委員会が解散した後も、孤

独に取り組む全政党のグループを率い続けている。2020年現在、ジョー・コックス財団は、政府との連携や他の慈善団体と協力して孤独の問題に取り組んで

います[2][1]。 2018年1月、テリーザ・メイ首相は最終報告書の提言を受け入れ、孤独を担当する閣僚の主席を創設し、この新しい役割により、孤独の解消が議会の永続的 な優先事項であり続けることを意図している。この役職は、メディアでは「孤独担当大臣」と呼ばれることが多いが、別の大臣室ではない。当初、この役職は、 スポーツ・市民社会担当大臣の権限を拡大したものでした。このポストは最初トレイシー・クラウチが務め、2018年11月から2019年7月まではミム ス・デイヴィスが務め、2020年現在ではバラン男爵夫人が務めている。2018年10月、やはり最終報告の結果、英国政府は世界で初めて孤独解消戦略を 発表しました。この戦略には、9つの異なる政府省庁による孤独解消活動のコミットメントが含まれており、例えば、第一線の医師による「社会的処方」を奨励 し、孤独に苦しむ患者を地域のグループ活動&親睦スキームに紹介できるようにすることなどが挙げられています。2020年5月現在、英国政府は孤独を減ら すためのさまざまな取り組みに2,000万ポンド以上を分配しています。この取り組みには、孤独と闘うことを目的とした慈善団体への資金提供や、テック企 業やコミュニティグループの両方が運営する孤独解消プロジェクトへの資金提供が含まれています[3][6][7][8][1]。 |

| 孤独・孤立対策官民連携プラットフォーム https://www.cas.go.jp/jp/seisaku/kodoku_koritsu_platform/history/index.html |

リンク(情動・感覚)

リンク(ナルシズム・ナルシシズム)

リンク(孤独)

リンク(雑多な)

文献(参照文献)

文献(タークル先生関連)

その他の情報