政治

Politics

☆ 政治[Politics](古 代ギリシャ語のπολιτικά(politiká)「都市の事務」に由来)とは、集団における意思決定や、地位や資源の分配など、個人間の権力関係の他 の形態に関連する活動の集合である。政治や政府を研究する社会科学の一分野は政治学と呼ばれる。「 政治的解決」という文脈では、妥協的で非暴力的な意味で肯定的に用いられることもあるが、「政治の芸術または科学」という表現では記述的に用いられること もあるが、否定的な意味合いを持つことも多い。この概念はさまざまな方法で定義されており、政治を広範囲に用いるべきか限定的に用いるべきか、経験的に用 いるべきか規範的に用いるべきか、また、対立よりも協力がより重要であるかなど、異なるアプローチでは根本的に異なる見解がある。

★政治には、自らの政治的見解を人々に広めること、他の政治主体との交渉、法律の制定、敵対者に対する戦争を含む内外の武力行使など、さまざまな方法が用い られる。政治は、伝統的社会の氏族や部族から、現代の地方自治体、企業、機関、主権国家、国際レベルに至るまで、幅広い社会レベルで行使される。 近代国家では、人々はしばしば自分たちの考えを代表する政党を結成する。政党のメンバーは多くの問題について同じ立場を取ることに同意し、同じ法律の改正 や同じ指導者を支持することに同意することが多い。

☆選挙は通常、異なる政党間の競争である。 政治システムとは、社会において許容される政治的手法を定義する枠組みである。政治思想の歴史は古代初期まで遡ることができ、プラトンの『国家』、アリス トテレスの『政治学』、孔子の政治に関する原稿、チャナクヤの『アーサーシャストラ』などの先駆的な著作がある。

| Politics (from

Ancient Greek πολιτικά (politiká) 'affairs of the cities') is the set

of activities that are associated with making decisions in groups, or

other forms of power relations among individuals, such as the

distribution of status or resources. The branch of social science that

studies politics and government is referred to as political science. They may be used positively in the context of a "political solution" which is compromising and non-violent,[1] or descriptively as "the art or science of government", but also often carries a negative connotation.[2] The concept has been defined in various ways, and different approaches have fundamentally differing views on whether it should be used extensively or in a limited way, empirically or normatively, and on whether conflict or co-operation is more essential to it. A variety of methods are deployed in politics, which include promoting one's own political views among people, negotiation with other political subjects, making laws, and exercising internal and external force, including warfare against adversaries.[3][4][5][6][7] Politics is exercised on a wide range of social levels, from clans and tribes of traditional societies, through modern local governments, companies and institutions up to sovereign states, to the international level. In modern nation states, people often form political parties to represent their ideas. Members of a party often agree to take the same position on many issues and agree to support the same changes to law and the same leaders. An election is usually a competition between different parties. A political system is a framework which defines acceptable political methods within a society. The history of political thought can be traced back to early antiquity, with seminal works such as Plato's Republic, Aristotle's Politics, Confucius's political manuscripts and Chanakya's Arthashastra.[8] |

政治(古代ギリシャ語のπολιτικά(politiká)「都市の

事務」に由来)とは、集団における意思決定や、地位や資源の分配など、個人間の権力関係の他の形態に関連する活動の集合である。政治や政府を研究する社会

科学の一分野は政治学と呼ばれる。 「政治的解決」という文脈では、妥協的で非暴力的な意味で肯定的に用いられることもあるが[1]、「政治の芸術または科学」という表現では記述的に用いられ ることもあるが、否定的な意味合いを持つことも多い[2]。この概念はさまざまな方法で定義されており、政治を広範囲に用いるべきか限定的に用いるべき か、経験的に用いるべきか規範的に用いるべきか、また、対立よりも協力がより重要であるかなど、異なるアプローチでは根本的に異なる見解がある。 政治には、自らの政治的見解を人々に広めること、他の政治主体との交渉、法律の制定、敵対者に対する戦争を含む内外の武力行使など、さまざまな方法が用い られる。政治は、伝統的社会の氏族や部族から、現代の地方自治体、企業、機関、主権国家、国際レベルに至るまで、幅広い社会レベルで行使される。 近代国家では、人々はしばしば自分たちの考えを代表する政党を結成する。政党のメンバーは多くの問題について同じ立場を取ることに同意し、同じ法律の改正 や同じ指導者を支持することに同意することが多い。選挙は通常、異なる政党間の競争である。 政治システムとは、社会において許容される政治的手法を定義する枠組みである。政治思想の歴史は古代初期まで遡ることができ、プラトンの『国家』、アリス トテレスの『政治学』、孔子の政治に関する原稿、チャナクヤの『アーサーシャストラ』などの先駆的な著作がある。 |

| Etymology The English politics has its roots in the name of Aristotle's classic work, Politiká, which introduced the Ancient Greek term politiká (Πολιτικά, 'affairs of the cities'). In the mid-15th century, Aristotle's composition would be rendered in Early Modern English as Polettiques [sic],[a][9] which would become Politics in Modern English. The singular politic first attested in English in 1430, coming from Middle French politique—itself taking from politicus,[10] a Latinization of the Greek πολιτικός (politikos) from πολίτης (polites, 'citizen') and πόλις (polis, 'city').[11] Definitions Harold Lasswell: "who gets what, when, how"[12] David Easton: "the authoritative allocation of values for a society"[13] Vladimir Lenin: "the most concentrated expression of economics"[14] Otto von Bismarck: "the capacity of always choosing at each instant, in constantly changing situations, the least harmful, the most useful"[15] Bernard Crick: "a distinctive form of rule whereby people act together through institutionalized procedures to resolve differences"[16] Adrian Leftwich: "comprises all the activities of co-operation, negotiation and conflict within and between societies"[17] |

語源 英語の「ポリティクス」という語は、古代ギリシャ語の「ポリティカ」(Πολιτικά、都市の事柄)という用語を導入したアリストテレスの古典的名著 『ポリティカ』にその語源がある。15世紀半ば、アリストテレスの著作は初期近代英語では『Polettiques』と表記されていたが[a][9]、こ れが近代英語では『Politics』となった。 英語における「ポリティクス」の単数形「ポリティック」は、1430年に初めて確認されており、これは中世フランス語の「ポリティーク」に由来する。「ポ リティーク」自体は、ギリシャ語の「ポリティコス(πολιτικός、ポリティコス)」に由来するラテン語化された「ポリテス(polites、ポリテ ス、『市民』)」と「ポリス(polis、ポリス、『都市』)」から派生したものである。 定義 ハロルド・ラスウェル:「誰が何を、いつ、どのようにして手に入れるか」[12] デビッド・イーストン:「社会における価値の権威ある配分」[13] ウラジーミル・レーニン:「経済学の最も凝縮された表現」[14] オットー・フォン・ビスマルク:「常に変化する状況において、常に、最も害が少なく、最も有益なものを選択する能力」[15] バーナード・クリック:「人々が制度化された手続きを通じて協力し合い、相違点を解消する独特な統治形態」[16] エイドリアン・レフトウィッチ:「社会内および社会間の協力、交渉、対立のすべての活動から構成される」[17] |

| Approaches There are several ways in which approaching politics has been conceptualized. Extensive and limited Adrian Leftwich has differentiated views of politics based on how extensive or limited their perception of what accounts as 'political' is.[18] The extensive view sees politics as present across the sphere of human social relations, while the limited view restricts it to certain contexts. For example, in a more restrictive way, politics may be viewed as primarily about governance,[19] while a feminist perspective could argue that sites which have been viewed traditionally as non-political, should indeed be viewed as political as well.[20] This latter position is encapsulated in the slogan "the personal is political", which disputes the distinction between private and public issues. Politics may also be defined by the use of power, as has been argued by Robert A. Dahl.[21] Moralism and realism Some perspectives on politics view it empirically as an exercise of power, while others see it as a social function with a normative basis.[22] This distinction has been called the difference between political moralism and political realism.[23] For moralists, politics is closely linked to ethics, and is at its extreme in utopian thinking.[23] For example, according to Hannah Arendt, the view of Aristotle was that "to be political…meant that everything was decided through words and persuasion and not through violence;"[24] while according to Bernard Crick "politics is the way in which free societies are governed. Politics is politics, and other forms of rule are something else."[25] In contrast, for realists, represented by those such as Niccolò Machiavelli, Thomas Hobbes, and Harold Lasswell, politics is based on the use of power, irrespective of the ends being pursued.[26][23] Conflict and co-operation Agonism argues that politics essentially comes down to conflict between conflicting interests. Political scientist Elmer Schattschneider argued that "at the root of all politics is the universal language of conflict,"[27] while for Carl Schmitt the essence of politics is the distinction of 'friend' from foe'.[28] This is in direct contrast to the more co-operative views of politics by Aristotle and Crick. However, a more mixed view between these extremes is provided by Irish political scientist Michael Laver, who noted that: Politics is about the characteristic blend of conflict and co-operation that can be found so often in human interactions. Pure conflict is war. Pure co-operation is true love. Politics is a mixture of both.[29] |

アプローチ 政治へのアプローチには、いくつかの方法が考えられている。 広義と狭義 エイドリアン・レフトウィッチは、「政治的」と見なされるものの認識がどの程度広義であるか、あるいは狭義であるかによって、政治に対する見解を区別して いる。[18] 広義の見解では、政治は人間の社会的関係の領域全体に存在すると見なしているが、狭義の見解では、政治を特定の文脈に限定している。例えば、より限定的な 見方では、政治とは主に統治に関するものであると見なされる可能性がある[19]。一方、フェミニストの視点では、伝統的に非政治的と見なされてきた領域 も、実際には政治的であると見なされるべきであると主張される可能性がある[20]。この後者の立場は、「個人的なことは政治的なことである」というス ローガンに集約されており、これは、私的な問題と公的な問題の区別を否定するものである。また、ロバート・A・ダールが主張しているように、政治は権力の 行使によって定義される場合もある。[21] 道徳主義と現実主義(モラリズム〈対〉リアリズム) 政治に関する見解の中には、政治を経験的に権力の行使として捉えるものがある一方で、規範的な基盤を持つ社会的機能として捉えるものもある。[22] この区別は、政治的な道徳主義と政治的な現実主義の違いと呼ばれている。[23] 道徳主義者にとって、政治は倫理と密接に関連しており、その極端な例が 。例えば、ハンナ・アレントによれば、アリストテレスの見解は「政治的であるということは、すべてが言葉と説得によって決定され、暴力によって決定されな いことを意味する」というものであった。[24] 一方、バーナード・クリックによれば、「政治とは自由な社会が統治される方法である。政治は政治であり、他の統治形態はまた別物である」[25] これに対し、ニッコロ・マキャベリ、トマス・ホッブズ、ハロルド・ラスウェルらに代表されるリアリストにとっては、政治とは追求される目的に関わらず、権 力の行使に基づくものである。[26][23] 対立と協力 アゴニズムは、政治の本質は対立する利害間の対立に帰結すると主張する。政治学者エルマー・シャトシュナイダーは「政治の根底には普遍的な対立がある」と 主張し[27]、カール・シュミットは政治の本質は「敵」と「味方」の区別にあると主張した[28]。これはアリストテレスやクリックの政治観である協調 的な見解とは対照的である。しかし、アイルランドの政治学者マイケル・レイバーは、これらの両極端な見解の中間的な見解を示しており、次のように述べてい る。 政治とは、人間同士の関わり合いにおいて頻繁に見られる、対立と協力の独特な融合である。純粋な対立は戦争であり、純粋な協力は真の愛である。政治とは、その両者の混合である。[29] |

| History Main article: Political history of the world See also: History of political thought  The Greek philosopher Aristotle criticized many of Plato's ideas as impracticable, but, like Plato, he admires balance and moderation and aims at a harmonious city under the rule of law.[30] The history of politics spans human history and is not limited to modern institutions of government. Prehistoric Frans de Waal argued that chimpanzees engage in politics through "social manipulation to secure and maintain influential positions."[31] Early human forms of social organization—bands and tribes—lacked centralized political structures.[32] These are sometimes referred to as stateless societies. Early states In ancient history, civilizations did not have definite boundaries as states have today, and their borders could be more accurately described as frontiers. Early dynastic Sumer, and early dynastic Egypt were the first civilizations to define their borders. Moreover, up to the 12th century, many people lived in non-state societies. These range from relatively egalitarian bands and tribes to complex and highly stratified chiefdoms. State formation Main article: State formation There are a number of different theories and hypotheses regarding early state formation that seek generalizations to explain why the state developed in some places but not others. Other scholars believe that generalizations are unhelpful and that each case of early state formation should be treated on its own.[33] Voluntary theories contend that diverse groups of people came together to form states as a result of some shared rational interest.[34] The theories largely focus on the development of agriculture, and the population and organizational pressure that followed and resulted in state formation. One of the most prominent theories of early and primary state formation is the hydraulic hypothesis, which contends that the state was a result of the need to build and maintain large-scale irrigation projects.[35] Conflict theories of state formation regard conflict and dominance of some population over another population as key to the formation of states.[34] In contrast with voluntary theories, these arguments believe that people do not voluntarily agree to create a state to maximize benefits, but that states form due to some form of oppression by one group over others. Some theories in turn argue that warfare was critical for state formation.[34] Ancient history The first states of sorts were those of early dynastic Sumer and early dynastic Egypt, which arose from the Uruk period and Predynastic Egypt respectively around approximately 3000 BC.[36] Early dynastic Egypt was based around the Nile River in the north-east of Africa, the kingdom's boundaries being based around the Nile and stretching to areas where oases existed.[37] Early dynastic Sumer was located in southern Mesopotamia, with its borders extending from the Persian Gulf to parts of the Euphrates and Tigris rivers.[36] Egyptians, Romans, and the Greeks were the first people known to have explicitly formulated a political philosophy of the state, and to have rationally analyzed political institutions. Prior to this, states were described and justified in terms of religious myths.[38] Several important political innovations of classical antiquity came from the Greek city-states (polis) and the Roman Republic. The Greek city-states before the 4th century granted citizenship rights to their free population; in Athens these rights were combined with a directly democratic form of government that was to have a long afterlife in political thought and history.[39] Modern states  Women voter outreach (1935) The Peace of Westphalia (1648) is considered by political scientists to be the beginning of the modern international system,[40][41][42] in which external powers should avoid interfering in another country's domestic affairs.[43] The principle of non-interference in other countries' domestic affairs was laid out in the mid-18th century by Swiss jurist Emer de Vattel.[44] States became the primary institutional agents in an interstate system of relations. The Peace of Westphalia is said to have ended attempts to impose supranational authority on European states. The "Westphalian" doctrine of states as independent agents was bolstered by the rise in 19th century thought of nationalism, under which legitimate states were assumed to correspond to nations—groups of people united by language and culture.[45] In Europe, during the 18th century, the classic non-national states were the multinational empires: the Austrian Empire, Kingdom of France, Kingdom of Hungary,[46] the Russian Empire, the Spanish Empire, the Ottoman Empire, and the British Empire. Such empires also existed in Asia, Africa, and the Americas; in the Muslim world, immediately after the death of Muhammad in 632, Caliphates were established, which developed into multi-ethnic transnational empires.[47] The multinational empire was an absolute monarchy ruled by a king, emperor or sultan. The population belonged to many ethnic groups, and they spoke many languages. The empire was dominated by one ethnic group, and their language was usually the language of public administration. The ruling dynasty was usually, but not always, from that group. Some of the smaller European states were not so ethnically diverse, but were also dynastic states, ruled by a royal house. A few of the smaller states survived, such as the independent principalities of Liechtenstein, Andorra, Monaco, and the republic of San Marino. Most theories see the nation state as a 19th-century European phenomenon, facilitated by developments such as state-mandated education, mass literacy, and mass media. However, historians[who?] also note the early emergence of a relatively unified state and identity in Portugal and the Dutch Republic.[48] Scholars such as Steven Weber, David Woodward, Michel Foucault, and Jeremy Black have advanced the hypothesis that the nation state did not arise out of political ingenuity or an unknown undetermined source, nor was it an accident of history or political invention.[49][34][50] Rather, the nation state is an inadvertent byproduct of 15th-century intellectual discoveries in political economy, capitalism, mercantilism, political geography, and geography[51][52] combined with cartography[53][54] and advances in map-making technologies.[55] Some nation states, such as Germany and Italy, came into existence at least partly as a result of political campaigns by nationalists, during the 19th century. In both cases, the territory was previously divided among other states, some of them very small. Liberal ideas of free trade played a role in German unification, which was preceded by a customs union, the Zollverein. National self-determination was a key aspect of United States President Woodrow Wilson's Fourteen Points, leading to the dissolution of the Austro-Hungarian Empire and the Ottoman Empire after the First World War, while the Russian Empire became the Soviet Union after the Russian Civil War. Decolonization lead to the creation of new nation states in place of multinational empires in the Third World. Globalization Main article: Political globalization Political globalization began in the 20th century through intergovernmental organizations and supranational unions. The League of Nations was founded after World War I, and after World War II it was replaced by the United Nations. Various international treaties have been signed through it. Regional integration has been pursued by the African Union, ASEAN, the European Union, and Mercosur. International political institutions on the international level include the International Criminal Court, the International Monetary Fund, and the World Trade Organization. |

歴史 詳細は「世界の政治史」を参照 政治思想史も参照  ギリシアの哲学者アリストテレスはプラトンの多くの考えを非現実的と批判したが、プラトンと同様に、彼はバランスと節度を賞賛し、法の支配による調和の取れた都市を目指した。 政治の歴史は人類の歴史にまたがり、現代の政府機関に限ったものではない。 先史時代 フランシス・ド・ワールは、チンパンジーは「影響力のある地位を確保し維持するための社会的操作」を通じて政治を行っていると主張している[31]。初期 の人類の社会組織である集団や部族には、中央集権的な政治構造は存在していなかった[32]。これらは時に無国家社会とも呼ばれる。 初期の国家 古代において、文明は今日のような国家としての明確な境界を持っておらず、その国境はより正確には辺境と表現される。初期王朝時代のシュメールや初期王朝 時代のエジプトは、国境を定めた最初の文明であった。さらに、12世紀まで、多くの人々は国家を持たない社会で暮らしていた。これには、比較的平等主義的 な集団や部族から、複雑で高度に階層化された首長国まで含まれる。 国家形成 詳細は「国家形成」を参照 初期の国家形成については、国家がなぜある場所では発展し、またある場所では発展しなかったのかを説明するための一般化を求める、さまざまな理論や仮説が存在する。他の学者は、一般化は役に立たず、初期の国家形成の事例はそれぞれ個別に扱われるべきだと考えている。 自発的理論は、共通の合理的な利害関係を共有する多様な人々の集団が国家を形成したと主張する。[34] この理論は主に農業の発展に焦点を当て、それに伴う人口と組織の圧力が国家形成につながったと主張する。初期の国家形成に関する最も著名な理論のひとつに 水利仮説がある。これは、国家は大規模な灌漑プロジェクトを建設し維持する必要性から生まれたと主張する。[35] 国家形成における対立理論では、ある集団が別の集団に対して優位に立つことや対立が国家形成の鍵であると考える。[34] 自発理論とは対照的に、これらの主張では、人々は利益を最大化するために自発的に国家の創設に合意するのではなく、ある集団が他の集団に対して何らかの形 で圧政を敷くことによって国家が形成されると考える。 一部の理論では、戦争が国家形成に極めて重要であったと主張している。[34] 古代史 最初の国家は、紀元前3000年頃にウルク時代から興った初期王朝時代シュメールと初期王朝時代エジプトである。初期王朝時代エジプトは、アフリカ北東部 のナイル川周辺を拠点としていた 、その国境はナイル川を中心にオアシスが存在する地域まで広がっていた。初期王朝時代のシュメールはメソポタミア南部に位置し、その国境はペルシア湾から ユーフラテス川とチグリス川の一部まで広がっていた。 エジプト人、ローマ人、ギリシア人は、国家の政治哲学を明確に定式化し、政治制度を合理的に分析した最初の民族として知られている。それ以前には、国家は宗教的な神話によって説明され、正当化されていた。 古典古代におけるいくつかの重要な政治的革新は、ギリシアの都市国家(ポリス)とローマ共和国から生まれた。4世紀以前のギリシアの都市国家は、自由民に 市民権を与えていた。アテネでは、これらの権利は直接民主制の形態と組み合わされ、政治思想と歴史において長い余韻を残すこととなった。 近代国家  女性有権者への働きかけ(1935年) ウェストファリア条約(1648年)は、政治学者たちによって近代国際システムの始まりとみなされている。このシステムでは、外部勢力は他国の内政への干 渉を避けるべきであるとされている。 3] 他国の内政への不干渉の原則は、18世紀半ばにスイスの法学者エマニュエル・ド・ヴァッテルによって提示された。ウェストファリア条約は、ヨーロッパ諸国 に超国家的な権限を課そうとする試みを終わらせたと言われている。国家を独立した主体とする「ウェストファリア」の原則は、19世紀に高まったナショナリ ズムの思想によって強化された。このナショナリズムの思想では、正当な国家は国民、すなわち言語と文化によって結びついた人々の集団に相当すると考えられ ていた。 ヨーロッパでは、18世紀には古典的な非国家国家として多民族帝国が存在していた。オーストリア帝国、フランス王国、ハンガリー王国[46]、ロシア帝 国、スペイン帝国、オスマン帝国、大英帝国などである。このような帝国はアジア、アフリカ、アメリカにも存在した。イスラム世界では、632年にムハンマ ドが死去した直後にカリフ制が確立し、多民族国家の超国家的な帝国へと発展した。多民族帝国は、国王、皇帝、またはスルタンによって統治される絶対君主制 であった。人口は多くの民族集団に属し、多くの言語が話されていた。帝国はひとつの民族集団によって支配され、その言語が通常は行政の言語であった。支配 王朝は、必ずしもそうとは限らないが、通常はその民族集団から出たものだった。ヨーロッパの小国家の中には、それほど民族的に多様ではなく、王家によって 支配される王朝国家もあった。リヒテンシュタイン、アンドラ、モナコの独立公国やサンマリノ共和国など、いくつかの小国家が存続している。 ほとんどの理論は、国民国家を19世紀のヨーロッパで起こった現象と見なしており、その要因として、国家による教育の義務化、大衆の識字率の向上、マスメ ディアの発達などを挙げている。しかし、歴史家[誰?]は、ポルトガルとオランダ共和国において比較的統一された国家とアイデンティティが早くから出現し ていたことも指摘している。[48] スティーブン・ウェーバー、デヴィッド・ウッドワード、ミシェル・フーコー、ジェレミー・ブラックなどの学者は、国民国家は政治的な才覚や未知の未確定な 源から生じたものではなく、また歴史の偶然や政治的な むしろ、国民国家は15世紀の政治経済学、資本主義、重商主義、政治地理学、地理学における知的発見[51][52]と、地図製作[53][54]および 地図製作技術の進歩[55]が組み合わさった結果、意図せずして生じた副産物である。 ドイツやイタリアなどの国家は、19世紀に民族主義者による政治運動の結果、少なくとも部分的に誕生した。いずれの場合も、その領土は以前は他の国家に分 割されており、その中には非常に小さな国家もあった。自由貿易の自由主義的な考え方はドイツ統一に一定の役割を果たしたが、ドイツ統一は関税同盟であるド イツ関税同盟に先行していた。民族自決は、ウッドロー・ウィルソン米国大統領の「14か条の要求」の主要な要素であり、第一次世界大戦後にオーストリア= ハンガリー帝国とオスマン帝国の崩壊につながった。一方、ロシア帝国はロシア内戦後にソビエト連邦となった。脱植民地化は、第三世界の多民族帝国に代わる 新たな国家の誕生につながった。 グローバル化 詳細は「政治のグローバル化」を参照 政治のグローバル化は、20世紀に政府間組織や超国家連合を通じて始まった。国際連盟は第一次世界大戦後に設立され、第二次世界大戦後に国際連合に置き換 わった。さまざまな国際条約が締結されている。地域統合はアフリカ連合、ASEAN、欧州連合、メルコスールによって推進されている。国際レベルにおける 国際政治機関には、国際刑事裁判所、国際通貨基金、世界貿易機関などがある。 |

| Political science This section needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources in this section. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. (December 2020) (Learn how and when to remove this message) Main article: Political science  Plato (left) and Aristotle (right), from a detail of The School of Athens, a fresco by Raphael. Plato's Republic and Aristotle's Politics secured the two Greek philosophers as two of the most influential political philosophers. The study of politics is called political science,[56] It comprises numerous subfields, namely three: Comparative politics, international relations and political philosophy.[57] Political science is related to, and draws upon, the fields of economics, law, sociology, history, philosophy, geography, psychology, psychiatry, anthropology, and neurosciences. Comparative politics is the science of comparison and teaching of different types of constitutions, political actors, legislature and associated fields. International relations deals with the interaction between nation-states as well as intergovernmental and transnational organizations. Political philosophy is more concerned with contributions of various classical and contemporary thinkers and philosophers.[58] Political science is methodologically diverse and appropriates many methods originating in psychology, social research, and cognitive neuroscience. Approaches include positivism, interpretivism, rational choice theory, behavioralism, structuralism, post-structuralism, realism, institutionalism, and pluralism. Political science, as one of the social sciences, uses methods and techniques that relate to the kinds of inquiries sought: primary sources such as historical documents and official records, secondary sources such as scholarly journal articles, survey research, statistical analysis, case studies, experimental research, and model building. |

政治学 この節には検証可能な参考文献や出典が全く示されていないか、不十分です。 この節には信頼できる出典を追加して記事の改善にご協力ください。 出典の記載がない内容は、異議申し立てにより削除される場合があります。 (2020年12月) (Learn how and when to remove this message) 詳細は「政治学」を参照  プラトン(左)とアリストテレス(右)、ラファエロによるフレスコ画『アテナイの学堂』の一部より。プラトンの『国家』とアリストテレスの『政治学』は、ギリシアの哲学者2人を最も影響力のある政治哲学者の2人として確立した。 政治学は政治科学とも呼ばれ、比較政治学、国際関係論、政治哲学の3つの分野を含む多数のサブフィールドから構成されている。政治学は経済学、法学、社会 学、歴史学、哲学、地理学、心理学、精神医学、人類学、神経科学などの分野と関連しており、それらの分野から影響を受けている。 比較政治学は、さまざまなタイプの憲法、政治的アクター、立法機関、関連分野の比較と教育を行う学問である。国際関係論は、国家間の相互作用、および政府間組織や超国家組織を扱う。政治哲学は、さまざまな古典的および現代的な思想家や哲学者の貢献により関心を寄せている。 政治学は方法論的に多様であり、心理学、社会調査、認知神経科学に由来する多くの手法を借用している。アプローチには、実証主義、解釈主義、合理的選択理 論、行動主義、構造主義、ポスト構造主義、現実主義、制度主義、多元主義などがある。政治学は社会科学の一分野であり、求められる調査の種類に関連する手 法や技術を用いる。一次資料としては、歴史的文書や公式記録などがあり、二次資料としては、学術誌論文、調査研究、統計分析、事例研究、実験研究、モデル 構築などがある。 |

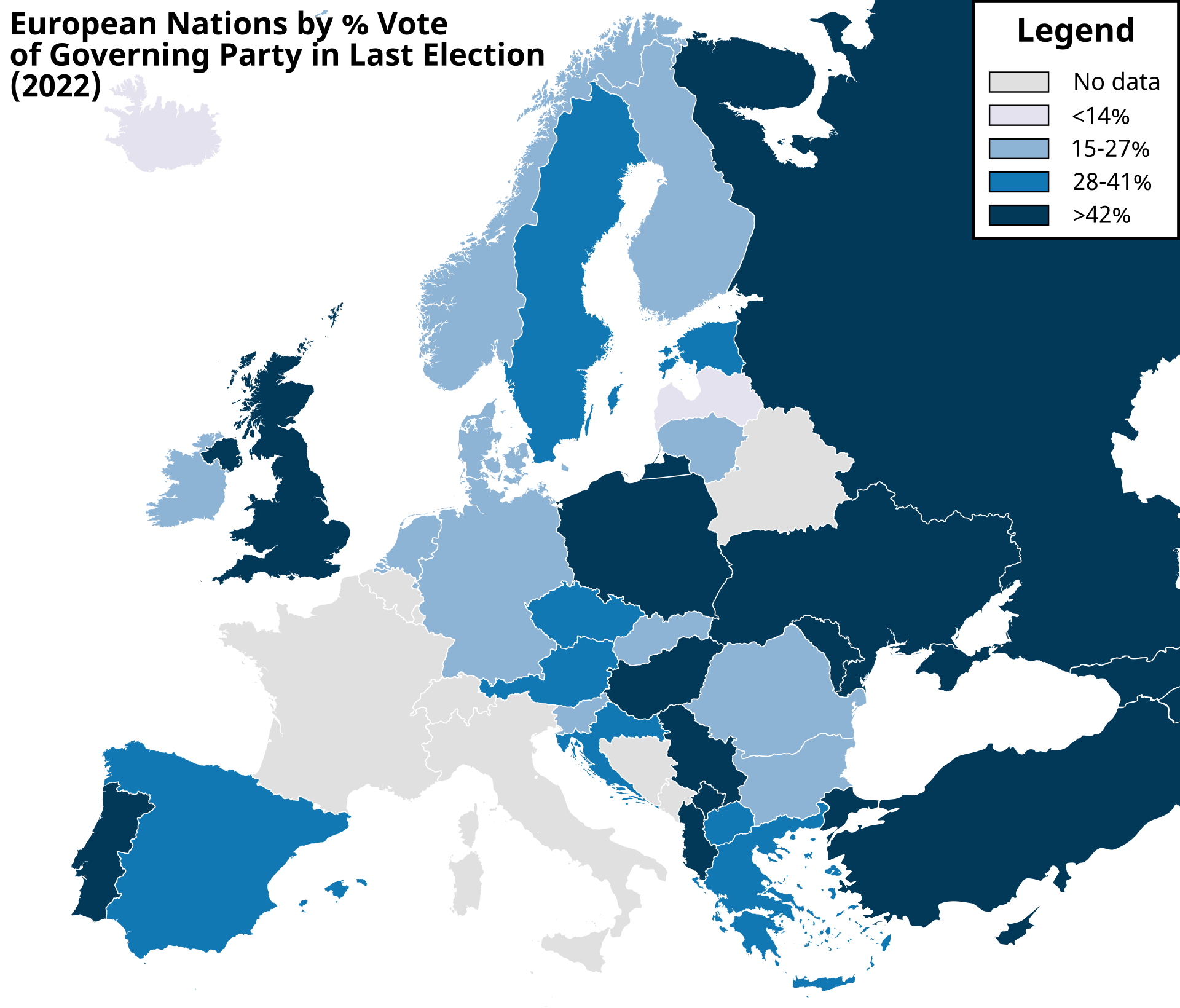

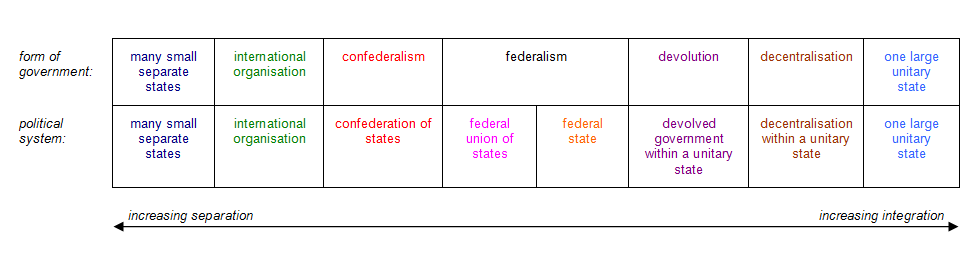

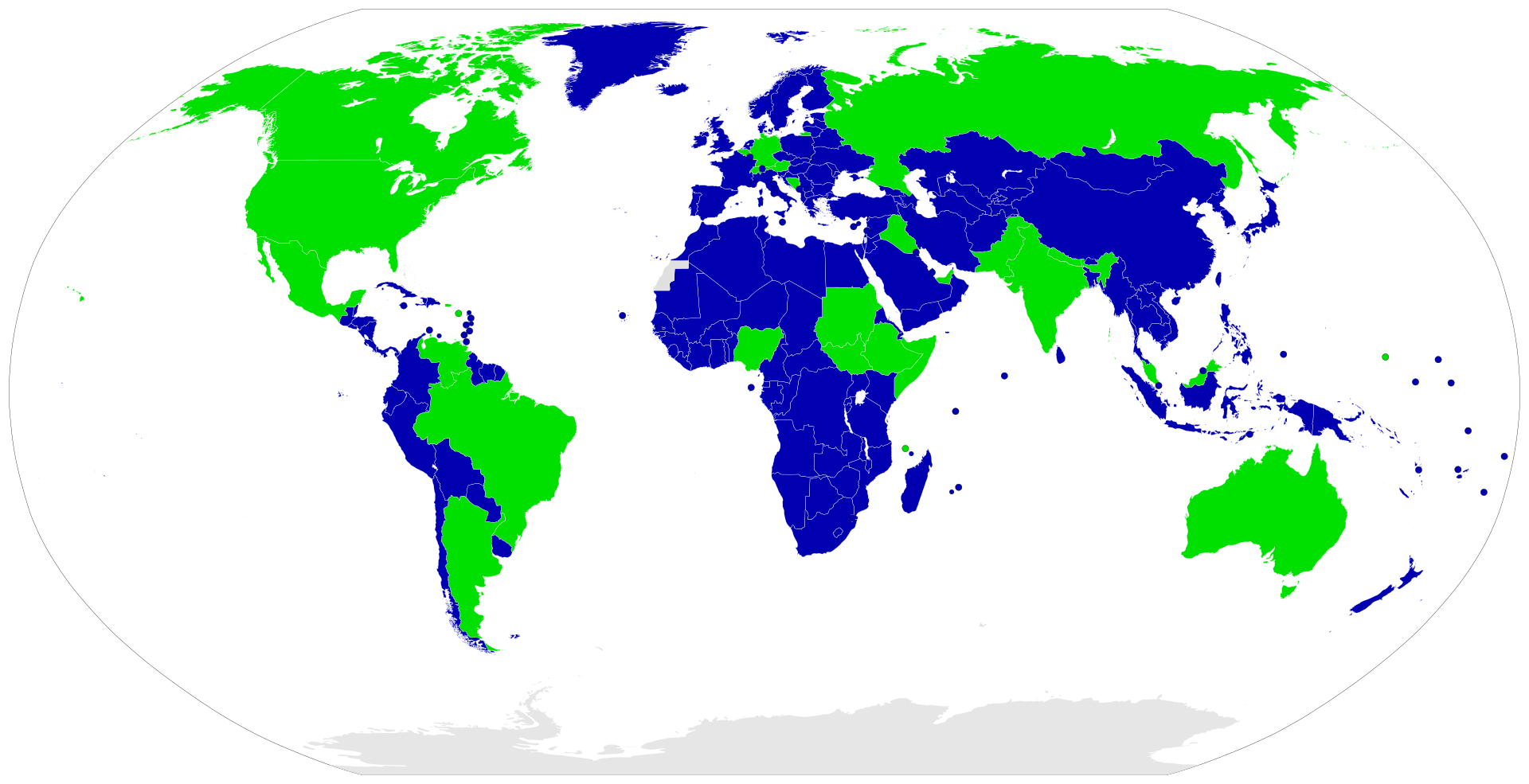

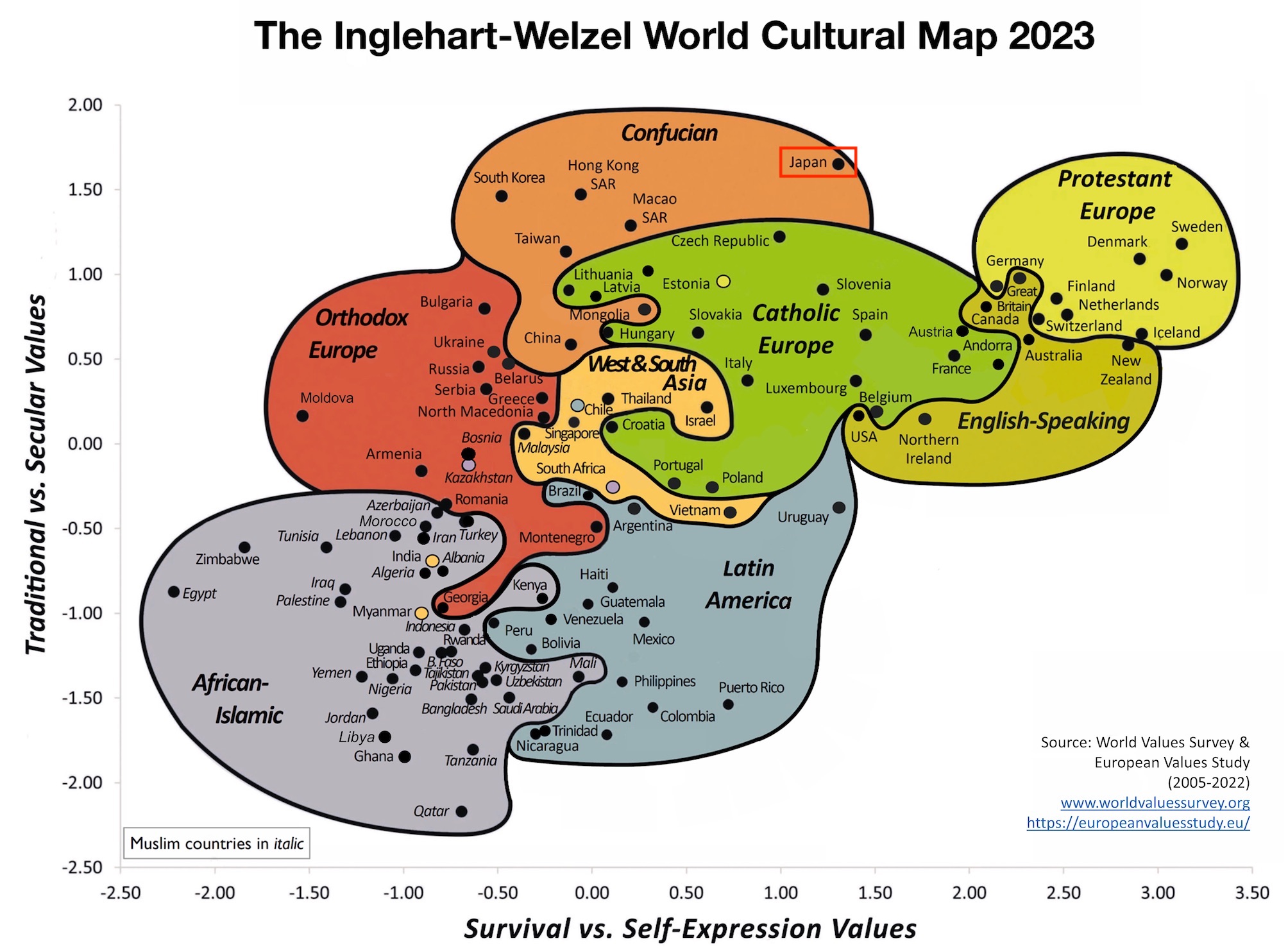

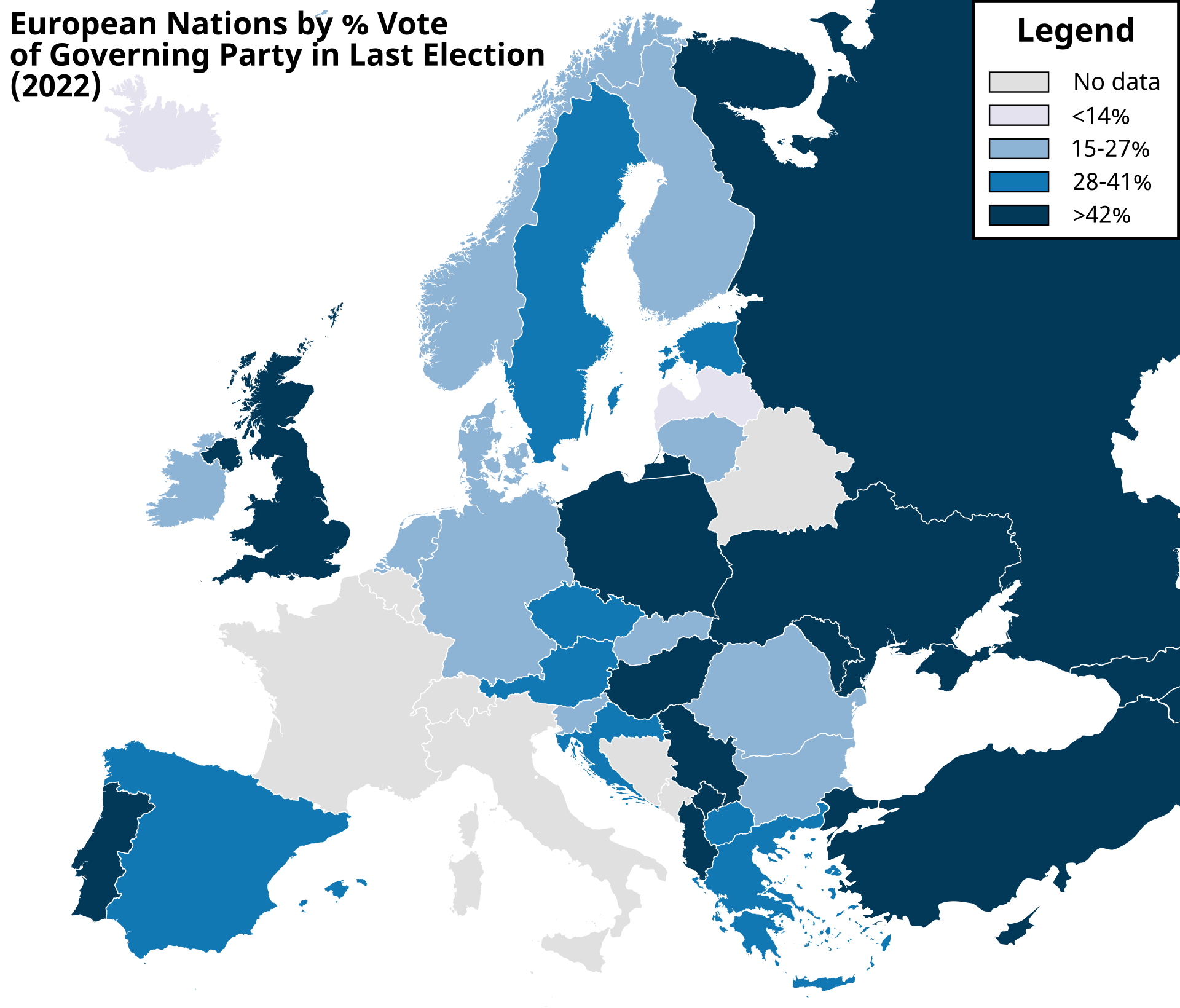

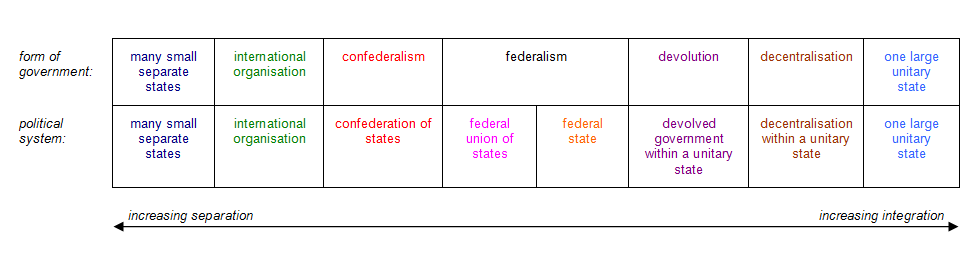

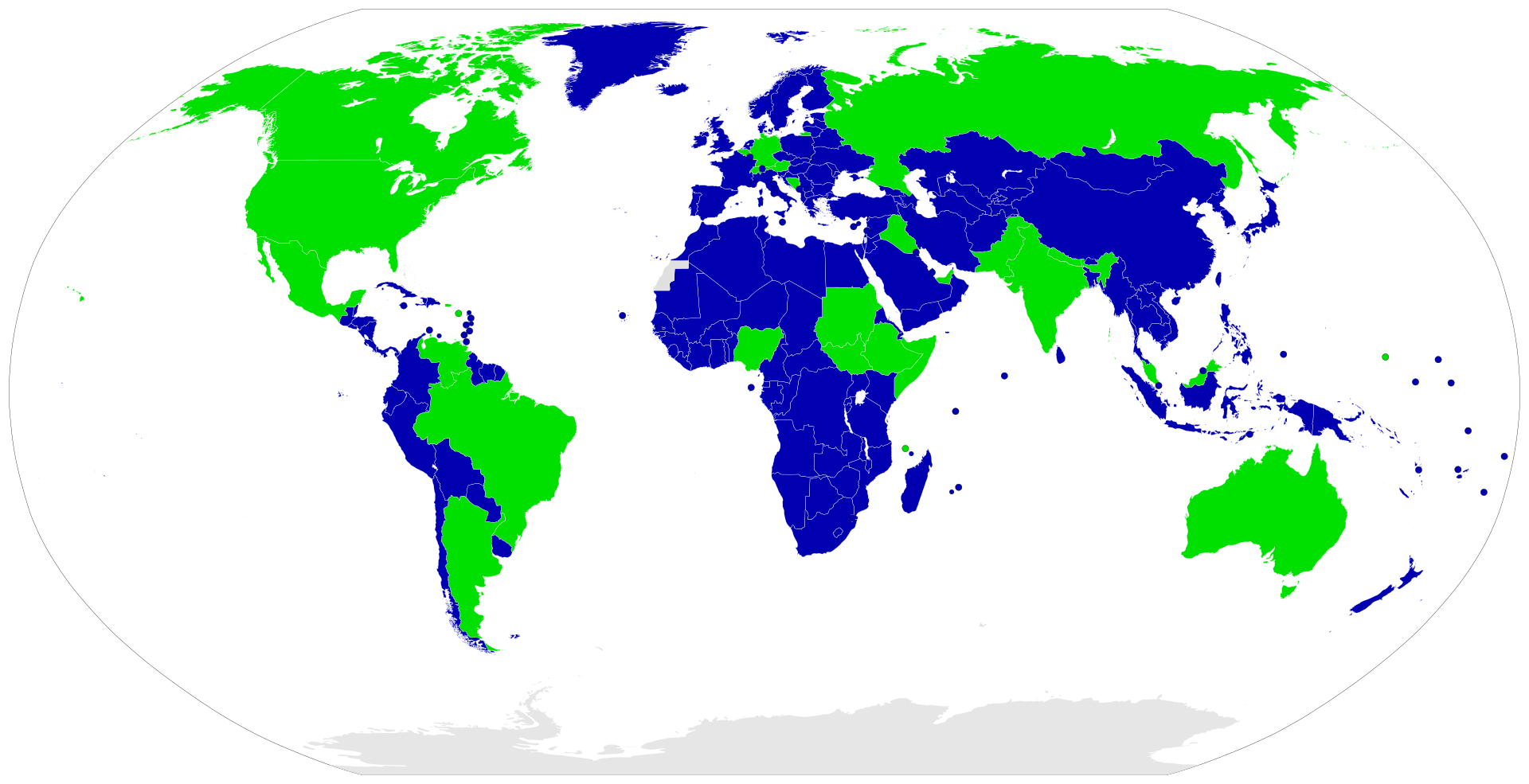

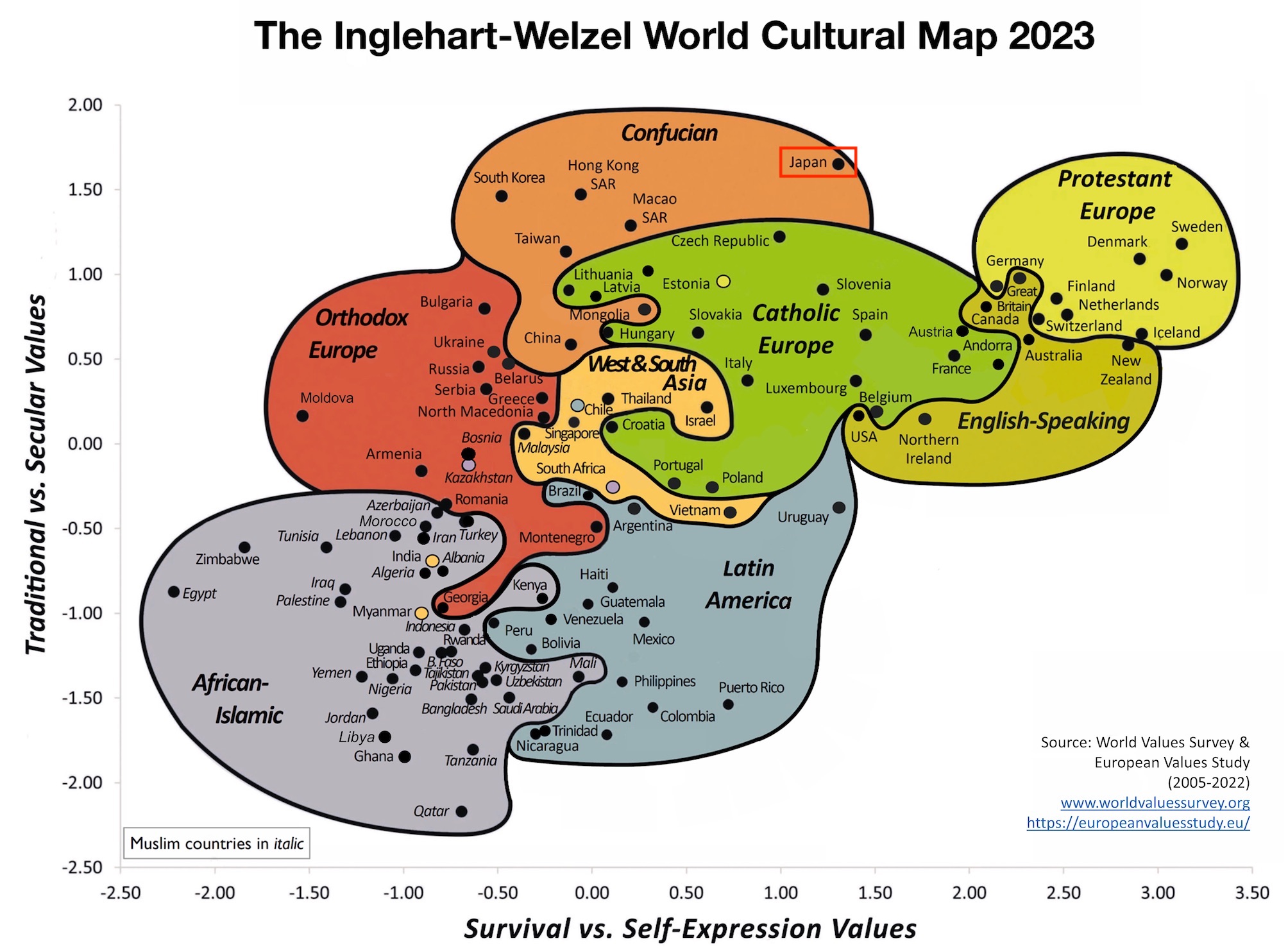

| Political system Main article: Political system See also: Systems theory in political science  Map of European nations coloured by percentage of vote governing party got in last election as of 2022 Systems view of politic s  The political system defines the process for making official government decisions. It is usually compared to the legal system, economic system, cultural system, and other social systems. According to David Easton, "A political system can be designated as the interactions through which values are authoritatively allocated for a society."[13] Each political system is embedded in a society with its own political culture, and they in turn shape their societies through public policy. The interactions between different political systems are the basis for global politics. Forms of government  Legislatures are an important political institution. Pictured is the Parliament of Finland. Forms of government can be classified by several ways. In terms of the structure of power, there are monarchies (including constitutional monarchies) and republics (usually presidential, semi-presidential, or parliamentary). The separation of powers describes the degree of horizontal integration between the legislature, the executive, the judiciary, and other independent institutions. Source of power The source of power determines the difference between democracies, oligarchies, and autocracies. In a democracy, political legitimacy is based on popular sovereignty. Forms of democracy include representative democracy, direct democracy, and demarchy. These are separated by the way decisions are made, whether by elected representatives, referendums, or by citizen juries. Democracies can be either republics or constitutional monarchies. Oligarchy is a power structure where a minority rules. These may be in the form of anocracy, aristocracy, ergatocracy, geniocracy, gerontocracy, kakistocracy, kleptocracy, meritocracy, noocracy, particracy, plutocracy, stratocracy, technocracy, theocracy, or timocracy. Autocracies are either dictatorships (including military dictatorships) or absolute monarchies.  The pathway of regional integration or separation Vertical integration In terms of level of vertical integration, political systems can be divided into (from least to most integrated) confederations, federations, and unitary states. A federation (also known as a federal state) is a political entity characterized by a union of partially self-governing provinces, states, or other regions under a central federal government (federalism). In a federation, the self-governing status of the component states, as well as the division of power between them and the central government, is typically constitutionally entrenched and may not be altered by a unilateral decision of either party, the states or the federal political body. Federations were formed first in Switzerland, then in the United States in 1776, in Canada in 1867 and in Germany in 1871 and in 1901, Australia. Compared to a federation, a confederation has less centralized power. State  Federal states Unitary states No government All the above forms of government are variations of the same basic polity, the sovereign state. The state has been defined by Max Weber as a political entity that has monopoly on violence within its territory, while the Montevideo Convention holds that states need to have a defined territory; a permanent population; a government; and a capacity to enter into international relations. A stateless society is a society that is not governed by a state.[59] In stateless societies, there is little concentration of authority; most positions of authority that do exist are very limited in power and are generally not permanently held positions; and social bodies that resolve disputes through predefined rules tend to be small.[60] Stateless societies are highly variable in economic organization and cultural practices.[61] While stateless societies were the norm in human prehistory, few stateless societies exist today; almost the entire global population resides within the jurisdiction of a sovereign state. In some regions nominal state authorities may be very weak and wield little or no actual power. Over the course of history most stateless peoples have been integrated into the state-based societies around them.[62] Some political philosophies consider the state undesirable, and thus consider the formation of a stateless society a goal to be achieved. A central tenet of anarchism is the advocacy of society without states.[59][63] The type of society sought for varies significantly between anarchist schools of thought, ranging from extreme individualism to complete collectivism.[64] In Marxism, Marx's theory of the state considers that in a post-capitalist society the state, an undesirable institution, would be unnecessary and wither away.[65] A related concept is that of stateless communism, a phrase sometimes used to describe Marx's anticipated post-capitalist society. Constitutions Constitutions are written documents that specify and limit the powers of the different branches of government. Although a constitution is a written document, there is also an unwritten constitution. The unwritten constitution is continually being written by the legislative and judiciary branch of government; this is just one of those cases in which the nature of the circumstances determines the form of government that is most appropriate.[66] England did set the fashion of written constitutions during the Civil War but after the Restoration abandoned them to be taken up later by the American Colonies after their emancipation and then France after the Revolution and the rest of Europe including the European colonies. Constitutions often set out separation of powers, dividing the government into the executive, the legislature, and the judiciary (together referred to as the trias politica), in order to achieve checks and balances within the state. Additional independent branches may also be created, including civil service commissions, election commissions, and supreme audit institutions. Political culture  Inglehart-Weltzel cultural map of countries Political culture describes how culture impacts politics. Every political system is embedded in a particular political culture.[67] Lucian Pye's definition is that "Political culture is the set of attitudes, beliefs, and sentiments, which give order and meaning to a political process and which provide the underlying assumptions and rules that govern behavior in the political system".[67] Trust is a major factor in political culture, as its level determines the capacity of the state to function.[68] Postmaterialism is the degree to which a political culture is concerned with issues which are not of immediate physical or material concern, such as human rights and environmentalism.[67] Religion has also an impact on political culture.[68] Political dysfunction Political corruption Main article: Political corruption Political corruption is the use of powers for illegitimate private gain, conducted by government officials or their network contacts. Forms of political corruption include bribery, cronyism, nepotism, and political patronage. Forms of political patronage, in turn, includes clientelism, earmarking, pork barreling, slush funds, and spoils systems; as well as political machines, which is a political system that operates for corrupt ends. When corruption is embedded in political culture, this may be referred to as patrimonialism or neopatrimonialism. A form of government that is built on corruption is called a kleptocracy ('rule of thieves'). Insincere politics The words "politics" and "political" are sometimes used as pejoratives to mean political action that is deemed to be overzealous, performative, or insincere.[69] |

政治体制 詳細は「政治体制」を参照 関連項目:政治学におけるシステム理論  2022年時点での前回の選挙における与党の得票率で色分けしたヨーロッパ諸国の地図 政治のシステム論  政治体制は、政府による公式な意思決定のプロセスを規定する。通常、法体系、経済体制、文化体制、その他の社会体制と比較される。デビッド・イーストンに よれば、「政治システムとは、社会に対して価値が権威をもって割り当てられる相互作用と定義できる」[13]。各政治システムは、独自の政治文化とともに 社会に組み込まれており、公共政策を通じて社会を形成している。異なる政治システム間の相互作用は、国際政治の基礎となっている。 政府の形態  立法機関は重要な政治制度である。写真はフィンランド議会。 政治体制はいくつかの方法で分類することができる。権力の構造という観点では、君主制(立憲君主制を含む)と共和制(通常は大統領制、半大統領制、議院内閣制)がある。 権力の分立は、立法府、行政府、司法府、およびその他の独立機関間の水平統合の度合いを説明する。 権力の源泉 権力の源泉は、民主主義、寡頭制、独裁制の違いを決定づける。 民主主義では、政治的正当性は人民主権に基づいている。民主主義の形態には、代表制民主主義、直接民主主義、デマクラシーがある。これらは、意思決定の方 法によって区別され、選出された代表者、国民投票、市民陪審のいずれかによって決定される。民主主義は共和制または立憲君主制である。 寡頭制は、少数派が支配する権力構造である。これは、無神論、貴族政治、労働政治、ジェニオクラシー、ジェロントクラシー、カキスクラシー、クレプトクラ シー、能力主義、ヌークラシー、パーティクラシー、プルトクラシー、ストラトクラシー、テクノクラシー、神政、または時間政治の形態をとる場合がある。 独裁制は、軍事独裁を含む独裁政権、または絶対君主制である。  地域統合または分離の経路 垂直統合 垂直統合のレベルという観点では、政治体制は(統合度が低い順に)連合、連邦、単一国家に分類される。 連邦(または連邦国家)は、中央政府(連邦制)の下で、部分的に自治権を持つ州、地域、またはその他の地域が統合された政治単位である。連邦では、構成州 の自治権、および州と中央政府間の権力分立は、通常、憲法で規定されており、州または連邦政府のいずれか一方の一方的な決定によって変更されることはな い。連邦は、まずスイスで、次いで1776年にアメリカ合衆国、1867年にカナダ、1871年と1901年にドイツで、そしてオーストラリアで結成され た。連邦に比べ、連合は中央集権的な力が弱い。 国家  連邦国家(緑) 単一国家(青) 政府なし(灰色) 上記のすべての形態の政府は、主権国家という同じ基本的な政治形態のバリエーションである。国家は、その領域内で暴力を独占する政治的実体としてマック ス・ウェーバーによって定義されている。一方、モンテビデオ条約では、国家には明確な領域、恒久的な人口、政府、国際関係を結ぶ能力が必要であるとしてい る。 国家を持たない社会とは、国家によって統治されていない社会である。[59] 国家を持たない社会では、権力が集中することはほとんどなく、存在する権力者の地位のほとんどは権力が非常に限定的であり、一般的に恒久的な地位ではな い。また、あらかじめ定められた規則によって紛争を解決する社会組織は小規模である傾向がある。[60] 国家を持たない社会は、経済組織や文化慣習において非常に多様である。[61] 無国籍社会は人類の有史以前には一般的であったが、今日では無国籍社会はほとんど存在せず、世界の人口のほぼすべてが主権国家の管轄内に居住している。一 部の地域では、名目上の国家権力が非常に弱く、実際の権力をほとんど、あるいはまったく行使していない場合もある。歴史を通じて、ほとんどの無国籍民族は 周囲の国家に基づく社会に統合されてきた。 国家を望ましくないものと考える政治哲学もあり、無国家社会の形成を達成すべき目標と考える。無政府主義の中心的な主張は、国家なき社会の提唱である。 [59][63] 無政府主義の学派によって、追求される社会のタイプは大きく異なり、極端な個人主義から完全な集団主義まで多岐にわたる。[64] マルクス主義では、マルクスの国家論は 国家に関するマルクスの理論では、ポスト資本主義社会では望ましくない制度である国家は不要となり、消滅すると考えられている。[65] 関連する概念として、国家なき共産主義という概念があり、これはマルクスが予期したポスト資本主義社会を表現する際に用いられることがある。 憲法 憲法は、政府の各部門の権限を規定し制限する文書である。憲法は文書であるが、不文憲法もある。不文憲法は、立法府と司法府によって絶えず書き換えられて いる。これは、状況の性質が最も適切な政府の形態を決定する、という事例のひとつである。[66] イングランドは、内戦中に憲法を文書化する流行を生み出したが、王政復古後にこれを放棄し、その後、アメリカ植民地が奴隷解放後に、そしてフランスが革命 後に、さらにヨーロッパ植民地を含むヨーロッパの他の地域がこれに続いた。 憲法は、国家内のチェックアンドバランスを実現するために、政府を行政、立法、司法(合わせて「三権政治」と呼ばれる)に分割し、三権分立を定めていることが多い。 また、公務員委員会、選挙管理委員会、最高監査機関など、独立した機関を追加で設ける場合もある。 政治文化  イングルハート=ウェルツェルによる各国の文化マップ 政治文化とは、文化が政治にどのような影響を与えるかを説明するものである。あらゆる政治体制は特定の政治文化に埋め込まれている。[67] ルシアン・パイの定義によると、「政治文化とは、政治プロセスに秩序と意味を与え、政治システムにおける行動を支配する基本的な前提と規則を提供する、態 度、信念、感情の集合体である」[67]。 信頼は政治文化における主要な要因であり、そのレベルは国家の機能能力を決定する。[68] ポストマテリアリズムとは、政治文化が人権や環境保護といった、即座に肉体や物質的な関心事ではない問題にどの程度関心を持っているかを表す度合いであ る。[67] 宗教もまた政治文化に影響を与える。[68] 政治の機能不全 政治腐敗 詳細は「政治腐敗」を参照 政治腐敗とは、政府高官やその人脈が、非合法な私的利益のために権力を行使することを指す。政治腐敗の形態には、賄賂、縁故主義、縁故採用、政治的恩恵な どがある。政治的恩恵の形態には、クライアントリズム、目的別予算、バラマキ予算、裏金、戦利品システムなどがあり、また政治マシンと呼ばれる、腐敗した 目的のために機能する政治システムもある。 汚職が政治文化に根付いている場合、これを家産主義または新家産主義と呼ぶことがある。汚職を基盤とする政治形態は、窃盗政治(「泥棒の支配」)と呼ばれる。 不誠実な政治 「政治」や「政治的」という言葉は、時に、過剰、パフォーマティビティ、不誠実とみなされる政治行動を意味する軽蔑的な表現として用いられることがある。[69] |

| Levels of politics Macropolitics Main article: Global politics Macropolitics can either describe political issues that affect an entire political system (e.g. the nation state), or refer to interactions between political systems (e.g. international relations).[70] Global politics (or world politics) covers all aspects of politics that affect multiple political systems, in practice meaning any political phenomenon crossing national borders. This can include cities, nation-states, multinational corporations, non-governmental organizations, and/or international organizations. An important element is international relations: the relations between nation-states may be peaceful when they are conducted through diplomacy, or they may be violent, which is described as war. States that are able to exert strong international influence are referred to as superpowers, whereas less-powerful ones may be called regional or middle powers. The international system of power is called the world order, which is affected by the balance of power that defines the degree of polarity in the system. Emerging powers are potentially destabilizing to it, especially if they display revanchism or irredentism. Politics inside the limits of political systems, which in contemporary context correspond to national borders, are referred to as domestic politics. This includes most forms of public policy, such as social policy, economic policy, or law enforcement, which are executed by the state bureaucracy. Mesopolitics Mesopolitics describes the politics of intermediary structures within a political system, such as national political parties or movements.[70] A political party is a political organization that typically seeks to attain and maintain political power within government, usually by participating in political campaigns, educational outreach, or protest actions. Parties often espouse an expressed ideology or vision, bolstered by a written platform with specific goals, forming a coalition among disparate interests.[71] Political parties within a particular political system together form the party system, which can be either multiparty, two-party, dominant-party, or one-party, depending on the level of pluralism. This is affected by characteristics of the political system, including its electoral system. According to Duverger's law, first-past-the-post systems are likely to lead to two-party systems, while proportional representation systems are more likely to create a multiparty system. Micropolitics Micropolitics describes the actions of individual actors within the political system.[70] This is often described as political participation.[72] Political participation may take many forms, including: Activism Boycott Civil disobedience Demonstration Petition Picketing Strike action Tax resistance Voting (or its opposite, abstentionism) |

政治のレベル マクロ政治 詳細は「グローバル政治」を参照 マクロ政治は、政治システム全体(例えば国民国家)に影響を与える政治問題を説明するものであるか、あるいは政治システム間の相互作用(例えば国際関係)を指すものである。 グローバル・ポリティクス(またはワールド・ポリティクス)は、複数の政治システムに影響を与える政治のあらゆる側面をカバーしており、実際には国境を越 えるあらゆる政治現象を意味する。これには、都市、国民国家、多国籍企業、非政府組織、および/または国際機関が含まれる。重要な要素は国際関係であり、 国民国家間の関係は、外交を通じて行われる場合は平和的であるが、戦争として表現されるような暴力的な場合もある。国際的に強い影響力を及ぼす国家は超大 国と呼ばれ、それほど強力でない国家は地域大国や中規模大国と呼ばれる。国際的な力の体系は世界秩序と呼ばれ、その体系における極性の度合いを定義する力 の均衡によって影響を受ける。新興勢力は、特に復讐主義や領土回復主義を示している場合、その体系を不安定化させる可能性がある。 政治システムの範囲内での政治、すなわち現代的な文脈では国境に相当するものは、国内政治と呼ばれる。これには、社会政策、経済政策、法の執行など、国家官僚によって実施されるほとんどの公共政策の形態が含まれる。 メゾ政治 メゾ政治とは、政治システム内の仲介構造の政治、例えば国家政党や運動などを指す。 政党は、通常は政治運動や教育支援、抗議行動への参加を通じて、政府内の政治的権力を獲得し維持しようとする政治組織である。政党はしばしば、特定の目標 を掲げた文書による綱領によって裏付けられた、明示されたイデオロギーやビジョンを支持し、さまざまな利害関係者間の連合を形成する。 特定の政治体制内の政党は、政党システムを形成する。政党システムは、多元主義の度合いによって、複数政党制、2大政党制、支配政党制、一党制のいずれか となる。これは選挙制度を含む政治体制の特性によって影響を受ける。デュベルジュの法則によると、小選挙区制は2大政党制につながりやすく、比例代表制は 複数政党制を生み出しやすい。 ミクロポリティクス ミクロポリティクスは、政治システム内における個々のアクターの行動を指す。[70] これはしばしば政治参加と表現される。[72] 政治参加には、以下のようなさまざまな形態がある。 活動 不買 市民的不服従 デモ 請願 ピケッティング ストライキ 租税抵抗 投票(またはその反対である棄権主義) |

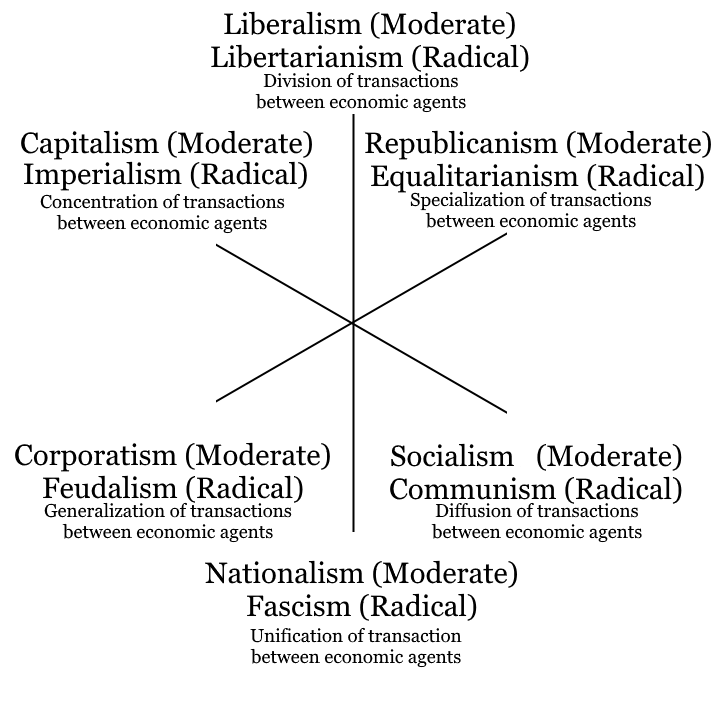

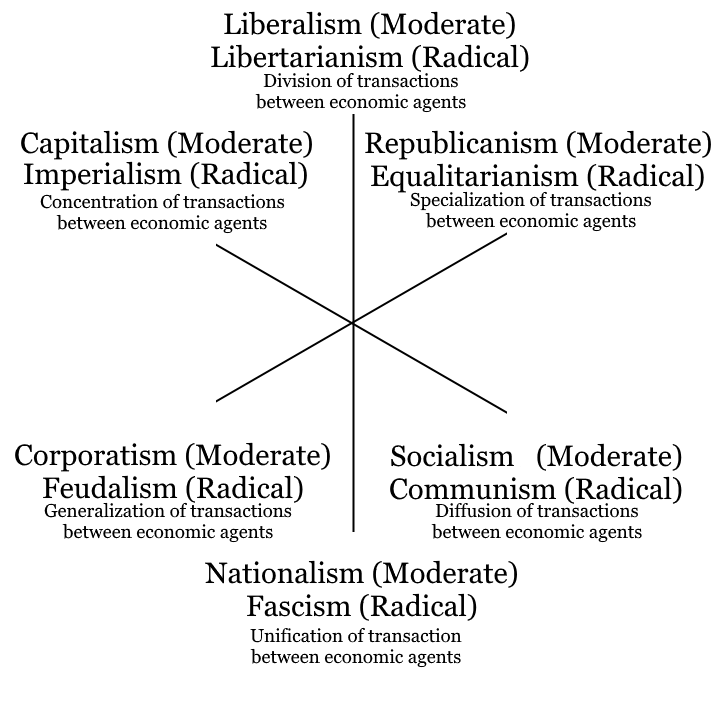

| Democracy Democracy is a system of processing conflicts in which outcomes depend on what participants do, but no single force controls what occurs and its outcomes. The uncertainty of outcomes is inherent in democracy. Democracy makes all forces struggle repeatedly to realize their interests and devolves power from groups of people to sets of rules.[73] Among modern political theorists, there are three contending conceptions of democracy: aggregative, deliberative, and radical.[74] Aggregative The theory of aggregative democracy claims that the aim of the democratic processes is to solicit the preferences of citizens, and aggregate them together to determine what social policies the society should adopt. Therefore, proponents of this view hold that democratic participation should primarily focus on voting, where the policy with the most votes gets implemented. Different variants of aggregative democracy exist. Under minimalism, democracy is a system of government in which citizens have given teams of political leaders the right to rule in periodic elections. According to this minimalist conception, citizens cannot and should not "rule" because, for example, on most issues, most of the time, they have no clear views or their views are not well-founded. Joseph Schumpeter articulated this view most famously in his book Capitalism, Socialism, and Democracy.[75] Contemporary proponents of minimalism include William H. Riker, Adam Przeworski, Richard Posner. According to the theory of direct democracy, on the other hand, citizens should vote directly, not through their representatives, on legislative proposals. Proponents of direct democracy offer varied reasons to support this view. Political activity can be valuable in itself, it socializes and educates citizens, and popular participation can check powerful elites. Most importantly, citizens do not rule themselves unless they directly decide laws and policies. Governments will tend to produce laws and policies that are close to the views of the median voter—with half to their left and the other half to their right. This is not a desirable outcome as it represents the action of self-interested and somewhat unaccountable political elites competing for votes. Anthony Downs suggests that ideological political parties are necessary to act as a mediating broker between individual and governments. Downs laid out this view in his 1957 book An Economic Theory of Democracy.[76] Robert A. Dahl argues that the fundamental democratic principle is that, when it comes to binding collective decisions, each person in a political community is entitled to have his/her interests be given equal consideration (not necessarily that all people are equally satisfied by the collective decision). He uses the term polyarchy to refer to societies in which there exists a certain set of institutions and procedures which are perceived as leading to such democracy. First and foremost among these institutions is the regular occurrence of free and open elections which are used to select representatives who then manage all or most of the public policy of the society. However, these polyarchic procedures may not create a full democracy if, for example, poverty prevents political participation.[77] Similarly, Ronald Dworkin argues that "democracy is a substantive, not a merely procedural, ideal."[78] Deliberative Main article: Deliberative democracy Deliberative democracy is based on the notion that democracy is government by deliberation. Unlike aggregative democracy, deliberative democracy holds that, for a democratic decision to be legitimate, it must be preceded by authentic deliberation, not merely the aggregation of preferences that occurs in voting. Authentic deliberation is deliberation among decision-makers that is free from distortions of unequal political power, such as power a decision-maker obtained through economic wealth or the support of interest groups.[79][80][81] If the decision-makers cannot reach consensus after authentically deliberating on a proposal, then they vote on the proposal using a form of majority rule. Radical Main article: Radical democracy Radical democracy is based on the idea that there are hierarchical and oppressive power relations that exist in society. Democracy's role is to make visible and challenge those relations by allowing for difference, dissent and antagonisms in decision-making processes. Equality  Two-axis political compass chart with a horizontal socio-economic axis and a vertical socio-cultural axis and ideologically representative political colours, an example for a frequently used model of the political spectrum[82][83][84][85][86][87][88][89]  Three axis model of political ideologies with both moderate and radical versions and the goals of their policies Main article: Social equality Equality is a state of affairs in which all people within a specific society or isolated group have the same social status, especially socioeconomic status, including protection of human rights and dignity, as well as access to certain social goods and social services. Furthermore, it may also include health equality, economic equality and other social securities. Social equality requires the absence of legally enforced social class or caste boundaries and the absence of discrimination based on by an inalienable aspect of a person's identity. To this end, there must be equal justice under law, and equal opportunity regardless of, sex, gender, ethnicity, age, sexual orientation, origin, caste or class, income or property, language, religion, convictions, opinions, health or disability. Left–right spectrum A common way of understanding politics is through the left–right political spectrum, which ranges from left-wing politics via centrism to right-wing politics. This classification is comparatively recent and dates from the French Revolution, when those members of the National Assembly who supported the republic, the common people and a secular society sat on the left and supporters of the monarchy, aristocratic privilege and the Church sat on the right.[90] Today, the left is generally progressivist, seeking social progress in society. The more extreme elements of the left, named the far-left, tend to support revolutionary means for achieving this. This includes ideologies such as Communism and Marxism. The center-left, on the other hand, advocates for more reformist approaches, for example that of social democracy. In contrast, the right is generally motivated by conservatism, which seeks to conserve what it sees as the important elements of society such as law and order, limited government and preserving individual freedoms. The far-right goes beyond this, and often represents a reactionary turn against progress, seeking to undo it. Examples of such ideologies have included Fascism and Nazism. The center-right may be less clear-cut and more mixed in this regard, with neoconservatives supporting the spread of free markets and capitalism, and one-nation conservatives more open to social welfare programs. According to Norberto Bobbio, one of the major exponents of this distinction, the left believes in attempting to eradicate social inequality—believing it to be unethical or unnatural,[91] while the right regards most social inequality as the result of ineradicable natural inequalities, and sees attempts to enforce social equality as utopian or authoritarian.[92] Some ideologies, notably Christian Democracy, claim to combine left and right-wing politics; according to Geoffrey K. Roberts and Patricia Hogwood, "In terms of ideology, Christian Democracy has incorporated many of the views held by liberals, conservatives and socialists within a wider framework of moral and Christian principles."[93] Movements which claim or formerly claimed to be above the left-right divide include Fascist Terza Posizione economic politics in Italy and Peronism in Argentina.[94][95] Freedom Main article: Political freedom Political freedom (also known as political liberty or autonomy) is a central concept in political thought and one of the most important features of democratic societies. Negative liberty has been described as freedom from oppression or coercion and unreasonable external constraints on action, often enacted through civil and political rights, while positive liberty is the absence of disabling conditions for an individual and the fulfillment of enabling conditions, e.g. economic compulsion, in a society. This capability approach to freedom requires economic, social and cultural rights in order to be realized. Authoritarianism and libertarianism Authoritarianism and libertarianism disagree the amount of individual freedom each person possesses in that society relative to the state. One author describes authoritarian political systems as those where "individual rights and goals are subjugated to group goals, expectations and conformities,"[96] while libertarians generally oppose the state and hold the individual as sovereign. In their purest form, libertarians are anarchists,[97] who argue for the total abolition of the state, of political parties and of other political entities, while the purest authoritarians are, by definition, totalitarians who support state control over all aspects of society.[98] For instance, classical liberalism (also known as laissez-faire liberalism)[99] is a doctrine stressing individual freedom and limited government. This includes the importance of human rationality, individual property rights, free markets, natural rights, the protection of civil liberties, constitutional limitation of government, and individual freedom from restraint as exemplified in the writings of John Locke, Adam Smith, David Hume, David Ricardo, Voltaire, Montesquieu and others. According to the libertarian Institute for Humane Studies, "the libertarian, or 'classical liberal,' perspective is that individual well-being, prosperity, and social harmony are fostered by 'as much liberty as possible' and 'as little government as necessary.'"[100] For anarchist political philosopher L. Susan Brown (1993), "liberalism and anarchism are two political philosophies that are fundamentally concerned with individual freedom yet differ from one another in very distinct ways. Anarchism shares with liberalism a radical commitment to individual freedom while rejecting liberalism's competitive property relations."[101] |

民主主義 民主主義とは、参加者の行動によって結果が左右されるが、その発生や結果を単一の勢力が支配することのない、対立を処理するシステムである。結果の不確実 性は民主主義に内在する。民主主義は、すべての勢力が自らの利益を実現するために繰り返し争い、権力を人々の集団から一連の規則へと委譲する。 現代の政治理論家たちの間では、民主主義に関する3つの対立する概念が存在する。集約的、熟議、急進的である。[74] 集約的 集約的民主主義の理論では、民主主義的プロセスは市民の希望を募り、それらを統合して社会が採用すべき社会政策を決定することが目的であると主張する。し たがって、この見解の支持者たちは、民主主義への参加は主に投票に焦点を当てるべきであり、最も多くの票を集めた政策が実施されるべきであると主張する。 集約的民主主義にはさまざまなバリエーションがある。ミニマリズムでは、民主主義とは、市民が政治指導者のチームに統治の権利を与えるシステムであり、そ の権利は定期的な選挙によって与えられる。このミニマリストの考え方によれば、市民は「統治」できないし、また統治すべきでもない。なぜなら、例えばほと んどの問題について、ほとんどの時間において、市民は明確な意見を持たないか、あるいはその意見は根拠のないものだからである。ジョセフ・シュンペーター は、この見解を著書『資本主義・社会主義・民主主義』で最も有名に述べている。[75] ミニマリズムの現代の支持者には、ウィリアム・H・ライカー、アダム・プシェウォルスキ、リチャード・ポズナーなどがいる。 一方、直接民主主義の理論によると、市民は立法案について、代表者を通じてではなく、直接投票すべきである。直接民主主義の支持者たちは、この見解を支持 するさまざまな理由を提示している。政治活動それ自体に価値がある。市民を社会化し、教育する。そして、一般市民の参加は強力なエリート層を牽制すること ができる。最も重要なのは、市民が法律や政策を直接決定しない限り、自分自身を統治することにはならないということだ。 政府は、有権者の意見の中央値に近い法律や政策を制定する傾向がある。これは、利己的で説明責任を欠く政治エリートたちが票の獲得を競い合うことを意味 し、望ましい結果とは言えない。アンソニー・ダウンズは、個人と政府の仲介者となるためには、イデオロギーに基づく政党が必要であると提言している。ダウ ンズは、1957年の著書『民主主義の経済理論』でこの見解を提示している。 ロバート・A・ダールは、拘束力のある集団的意思決定に関しては、政治社会の各個人は、自らの利益が平等に考慮される権利を有している(集団的意思決定に よって、必ずしも全ての人が平等に満足するわけではない)というのが、民主主義の基本原則であると主張している。 彼は、そのような民主主義につながると考えられる一定の制度や手続きが存在する社会を指して「ポリアーキー」という用語を使用している。こうした制度の中 でも最も重要なのは、社会の公共政策のすべてまたは大半を管理する代表者を選出するために定期的に実施される自由で開かれた選挙である。しかし、たとえば 貧困が政治参加を妨げる場合など、こうしたポリアーキー的な手続きは完全な民主主義を実現しない可能性がある。同様に、ロナルド・ドウォーキンは「民主主 義は単なる手続き的なものではなく、実質的な理想である」と主張している。 熟議 詳細は「熟議民主主義」を参照 熟議民主主義は、民主主義とは熟議による統治であるという考えに基づいている。集約民主主義とは異なり、熟議民主主義では、民主的な決定が正当であるため には、投票における単なる好みの集約ではなく、真正な熟議が先行しなければならないと主張する。真の熟議とは、意思決定者による、経済的な富や利益団体の 支援を通じて得られた権力といった不平等な政治的権力の歪みから自由な熟議である。[79][80][81] 意思決定者が提案について真の熟議を行った後で合意に達することができない場合、多数決の形式を用いてその提案について投票を行う。 急進的 詳細は「急進民主主義」を参照 急進民主主義は、社会には階層的で抑圧的な権力関係が存在するという考えに基づいている。民主主義の役割は、意思決定プロセスにおける相違、反対意見、対立を許容することで、それらの関係を可視化し、それらに異議を唱えることである。 平等  水平の社会経済軸と垂直の社会文化軸、およびイデオロギーを象徴する政治色を用いた2軸の政治コンパス図。政治スペクトラムのモデルとしてよく用いられる例[82][83][84][85][86][87][88][89]  穏健派と急進派の両方のバージョンと政策目標を持つ政治イデオロギーの3軸モデル 詳細は「社会的平等」を参照 平等とは、特定の社会または孤立した集団内のすべての人々が同じ社会的地位、特に社会経済的地位を持つ状態を指す。これには、人権と尊厳の保護、特定の社 会財や社会サービスへのアクセスが含まれる。さらに、健康の平等、経済的平等、その他の社会保障も含まれる場合がある。社会的平等は、法的に強制された社 会階級やカーストの境界線の欠如、および、個人のアイデンティティの不可分の側面に基づく差別の欠如を必要とする。この目的を達成するには、性別、ジェン ダー、民族、年齢、性的指向、出身、カーストや階級、収入や財産、言語、宗教、信念、意見、健康状態や障害の有無に関わらず、法の下の平等な正義と機会が なければならない。 左派/右派のスペクトラム 政治を理解する一般的な方法として、左派から右派までの政治スペクトラムがある。これは、左派政治から中道主義を経て右派政治までの範囲である。この分類 は比較的新しく、フランス革命の時代にさかのぼる。国民議会において、共和国、庶民、世俗社会を支持する議員は左側に、王政、貴族特権、教会を支持する議 員は右側に座った。 今日では、左派は一般的に社会進歩を求める進歩主義である。左派の中でも極端な要素を持つ極左は、これを達成するための革命的手段を支持する傾向にある。 これには共産主義やマルクス主義などのイデオロギーが含まれる。一方、中道左派は、社会民主主義などのより改革的なアプローチを提唱する。 これに対し、右派は一般的に保守主義を基盤としており、法と秩序、限定的な政府、個人の自由の保護など、社会の重要な要素を維持しようとする。極右はこれ を超えて、進歩に対する反動的な傾向を示すことが多く、それを覆そうとする。このようなイデオロギーの例としては、ファシズムやナチズムが挙げられる。中 道右派は、この点においてより明確ではなく、より混合的である可能性がある。新保守主義者は自由市場と資本主義の拡大を支持し、一党保守主義者は社会福祉 プログラムによりオープンである。 この区別を明確に主張する人物の一人であるノルベルト・ボビーオによると、左派は社会的不平等を根絶しようと試みることを信条としている。それは、不道徳 または不自然であると信じられているからである[91]。一方、右派はほとんどの社会的不平等を根絶できない自然的不平等の結果であると見なし、社会平等 を強制しようとする試みをユートピア的または権威主義的であると見なしている[92]。一部のイデオロギー、特にキリスト教民主主義は、左派と右派の政治 を組み合わせていると主張している 。ジェフリー・K・ロバーツとパトリシア・ホグウッドによると、「キリスト教民主主義は、道徳とキリスト教の原則というより広い枠組みの中で、リベラル 派、保守派、社会主義者の多くが持つ見解を取り入れている」という。[93] イタリアのファシスト第三の位置づけの経済政策やアルゼンチンのペロン主義など、かつては左右の対立軸を超えると主張していた、あるいは主張していた運動 もある。[94][95] 自由 詳細は「政治的自由」を参照 政治的自由(政治的自由、政治的自治とも)は政治思想の中心概念であり、民主的社会の最も重要な特徴のひとつである。消極的自由は、市民的および政治的権 利を通じてしばしば制定される、抑圧や強制、行動に対する不当な外部からの制約からの自由と説明される。一方、積極的自由は、社会における個人の障害とな る条件の不在と、経済的強制力などの実現条件の充足である。この自由に対する能力アプローチを実現するには、経済的、社会的、文化的権利が必要である。 権威主義とリバタリアニズム 権威主義とリバタリアニズムは、国家と比較した社会における個人の自由の程度について意見が分かれる。ある著者は、権威主義的政治体制を「個人の権利と目 標が集団の目標、期待、順応に従属する」体制と表現している[96]。一方、リバタリアンは一般的に国家に反対し、個人が主権者であると主張する。リバタ リアニズムの最も純粋な形は無政府主義であり、国家、政党、その他の政治的実体の完全な廃止を主張する。一方、権威主義の最も純粋な形は、定義上、社会の あらゆる側面に対する国家統制を支持する全体主義である。 例えば、古典的自由主義(自由放任主義とも呼ばれる)[99]は、個人の自由と限定的な政府を強調する教義である。これには、人間の理性の重要性、個人の 財産権、自由市場、自然権、市民的自由の保護、政府の憲法上の制限、そしてジョン・ロック、アダム・スミス、デイヴィッド・ヒューム、デイヴィッド・リ カード、ヴォルテール、モンテスキューなどの著作に見られるような、個人の自由の束縛からの解放が含まれる。リバタリアン・ヒューメイン・スタディーズ研 究所によると、「リバタリアン、つまり『古典的自由主義』の観点では、個人の幸福、繁栄、社会の調和は、『可能な限りの自由』と『必要最低限の政府』に よって促進されるというものである 」と主張している。[100] 政治哲学者のL.スーザン・ブラウン(1993年)は、「リベラリズムとアナーキズムは、基本的に個人の自由を重視する2つの政治哲学であるが、両者は非 常に異なる点で異なっている。アナーキズムはリベラリズムと個人の自由に対する急進的な献身を共有しているが、リベラリズムの競争的な財産関係は拒絶して いる」と述べている。[101] |

| Horseshoe theory Index of politics articles – alphabetical list of political subjects List of politics awards List of years in politics Outline of political science – structured list of political topics, arranged by subject area Political lists – lists of political topics Political polarization |

馬蹄形理論 政治記事の索引 – 政治主題のアルファベット順リスト 政治賞のリスト 政治における年表 政治学の概要 – 政治トピックの構造化されたリスト、主題分野別に分類 政治リスト – 政治トピックのリスト 政治的極化 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Politics |

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆