a kind of state

さまざまな国家論

a kind of state

「国家(state)」にはさまざまなとらえ方とその歴史的変遷があります。また、どのような国家観をとるか は、国家を操縦し、国民をなにがしかの生活空間に置き留めるのか、という(国家に帰属する)人々の理念の反映でもあります。しかしながら、国家という意味 も、現在の我々がいうそれと、マキャベリのそれが同じであるという保証はない。西洋思想のなかに国家に相当するものに以下のような語彙がある;ポリス(ギ リシア語)、コイノニア(ギリシア語)、レスプブリカ(ラテン語:res pibulica)、インペリウム(ラテン語: imperium)そして、中世のコムニタス・コムニタートゥム(ラテン語:comunitas communitatum)として、ステイト(英語:state)など。

| A state

is a political entity that regulates society and the population within

a definite territory.[1] Government is considered to form the

fundamental apparatus of contemporary states.[2][3] A country often has a single state, with various administrative divisions. A state may be a unitary state or some type of federal union; in the latter type, the term "state" is sometimes used to refer to the federated polities that make up the federation, and they may have some of the attributes of a sovereign state, except being under their federation and without the same capacity to act internationally. (Other terms that are used in such federal systems may include "province", "region" or other terms.) For most of prehistory, people lived in stateless societies. The earliest forms of states arose about 5,500 years ago.[4] Over time societies became more stratified and developed institutions leading to centralised governments. These gained state capacity in conjunction with the growth of cities, which was often dependent on climate and economic development, with centralisation often spurred on by insecurity and territorial competition. Over time, varied forms of states developed, that used many different justifications for their existence (such as divine right, the theory of the social contract, etc.). Today, the modern nation state is the predominant form of state to which people are subject.[5] Sovereign states have sovereignty; any ingroup's claim to have a state faces some practical limits via the degree to which other states recognize them as such. Satellite states are states that have de facto sovereignty but are often indirectly controlled by another state. Definitions of a state are disputed.[6][7] According to sociologist Max Weber, a "state" is a polity that maintains a monopoly on the legitimate use of violence, although other definitions are common.[8][9] Absence of a state does not preclude the existence of a society, such as stateless societies like the Haudenosaunee Confederacy that "do not have either purely or even primarily political institutions or roles".[10] The degree and extent of governance of a state is used to determine whether it has failed.[11] |

国家とは、特定の領域内で社会と住民を統制する政治的実体である。[1] 政府は現代国家の基本的な機構を構成すると考えられている。[2][3] 国は通常、単一の国家を有し、様々な行政区分が存在する。国家は単一国家である場合もあれば、何らかの連邦制国家である場合もある。後者の場合、「州」と いう用語は連邦を構成する加盟政治体を指すことがあり、それらは連邦に属していること、国際的に行動する能力が連邦と同等でないことを除けば、主権国家の 属性の一部を有していることがある。(このような連邦制で使用される他の用語には「州」「地域」などがある。) 先史時代の大半において、人々はその国家のない社会で暮らしていた。国家の最も初期の形態が誕生したのは約5500年前である[4]。時が経つにつれ、社 会はより階層化し、中央集権的な政府へと発展する制度が形成された。これらは都市の成長と連動して国家としての能力を獲得したが、その成長はしばしば気候 や経済発展に依存し、中央集権化は不安定さや領土競争によって促進されることが多かった。 時が経つにつれて、さまざまな形態の国家が発展し、その存在を正当化するためにさまざまな理論(神権説、社会契約論など)が用いられた。今日、現代的な国 民国家は、人民が従属する国家の主な形態となっている。[5] 主権国家は主権を有する。ある集団が国家であると主張する場合、他の国家がそれを国家として認める程度によって、その主張には実際的な限界が生じる。衛星 国家とは、事実上の主権を有するが、多くの場合、他の国家によって間接的に支配されている国家である。 国家の定義については議論がある。[6][7] 社会学者マックス・ヴェーバーによれば、「国家」とは、暴力の合法的な行使を独占する政治体制である。ただし、他の定義も一般的である。国家が存在しない 場合でも、社会は存在しうる。例えば、ホードノソーニー連邦のような国家を持たない社会は、「純粋に、あるいは主に政治的な制度や役割を持たない」社会で ある。国家の統治の程度と範囲は、その国家が機能不全に陥っているかどうかを判断するために用いられる。 |

| Etymology The word state and its cognates in some other European languages (stato in Italian, estado in Spanish and Portuguese, état in French, Staat in German and Dutch) ultimately derive from the Latin word status, meaning "condition, circumstances". Latin status derives from stare, "to stand", or remain or be permanent, thus providing the sacred or magical connotation of the political entity. The English noun state in the generic sense "condition, circumstances" predates the political sense. It was introduced to Middle English c. 1200 both from Old French and directly from Latin. With the revival of the Roman law in 14th-century Europe, the term came to refer to the legal standing of persons (such as the various "estates of the realm" – noble, common, and clerical), and in particular the special status of the king. The highest estates, generally those with the most wealth and social rank, were those that held power. The word also had associations with Roman ideas (dating back to Cicero) about the "status rei publicae", the "condition of public matters". In time, the word lost its reference to particular social groups and became associated with the legal order of the entire society and the apparatus of its enforcement.[12] The early 16th-century works of Machiavelli (especially The Prince) played a central role in popularizing the use of the word "state" in something similar to its modern sense.[13] The contrasting of church and state still dates to the 16th century.[14] The expression "L'État, c'est moi" ("I am the State") attributed to Louis XIV, although probably apocryphal, is recorded in the late 18th century.[15] |

語源 「国家」という言葉と、他のいくつかのヨーロッパ言語における同源語(イタリア語のstato、スペイン語とポルトガル語のestado、フランス語の état、ドイツ語とオランダ語のStaat)は、最終的にはラテン語のstatusに由来する。これは「状態、状況」を意味する。ラテン語の statusはstare(立つ、留まる、永続する)に由来し、それゆえ政治的実体に対する神聖または呪術的な含意を与えている。 英語の名詞stateが「状態、状況」という一般的な意味で使われるのは、政治的な意味よりも古い。この用法は中英語期(約1200年頃)に、古フランス語経由とラテン語からの直接借用によって導入された。 14世紀ヨーロッパにおけるローマ法の復興に伴い、この用語は人格の法的地位(貴族、平民、聖職者といった様々な「三身分」など)を指すようになり、特に 王の特別な地位を指すようになった。最高位の身分、一般に最も富と社会的地位を持つ者たちが権力を握っていた。この語はまた、キケロに遡る「公共の事柄の 状態(status rei publicae)」に関するローマ思想とも関連していた。やがてこの語は特定の社会集団を指す意味を失い、社会全体の法秩序とその執行機構と結びつくよ うになった。[12] 16世紀初頭のマキアヴェッリの著作(特に『君主論』)は、「国家」という語を現代に近い意味で普及させる上で中心的な役割を果たした。[13] 教会と国家の対比も16世紀に遡る。[14] ルイ14世に帰せられる「国家とは我なり(L『État, c』est moi)」という表現は、おそらく偽伝であるが、18世紀後半に記録されている。[15] |

| Definition There is no academic consensus on the definition of the state.[6] The term "state" refers to a set of different, but interrelated and often overlapping, theories about a certain range of political phenomena.[7] According to Walter Scheidel, mainstream definitions of the state have the following in common: "centralized institutions that impose rules, and back them up by force, over a territorially circumscribed population; a distinction between the rulers and the ruled; and an element of autonomy, stability, and differentiation. These distinguish the state from less stable forms of organization, such as the exercise of chiefly power."[16] The most commonly used definition is by Max Weber[17][18][19][20][21] who describes the state as a compulsory political organization with a centralized government that maintains a monopoly of the legitimate use of force within a certain territory.[8][9] Weber writes that the state "is a human community that (successfully) claims the monopoly of the legitimate use of physical force within a given territory."[22] While defining a state, it is important not to confuse it with a nation; an error that occurs frequently in common discussion. A state refers to a political unit with sovereignty over a given territory.[23] While a state is more of a "political-legal abstraction," the definition of a nation is more concerned with political identity and cultural or historical factors.[23] Importantly, nations do not possess the organizational characteristics like geographic boundaries or authority figures and officials that states do.[23] Additionally, a nation does not have a claim to a monopoly on the legitimate use of force over their populace,[23] while a state does, as Weber indicated. An example of the instability that arises when a state does not have a monopoly on the use of force can be seen in African states which remain weak due to the lack of war which European states relied on.[24] A state should not be confused with a government; a government is an organization that has been granted the authority to act on the behalf of a state.[23] Nor should a state be confused with a society; a society refers to all organized groups, movements, and individuals who are independent of the state and seek to remain out of its influence.[23] Neuberger offers a slightly different definition of the state with respect to the nation: the state is "a primordial, essential, and permanent expression of the genius of a specific [nation]."[25] The definition of a state is also dependent on how and why they form. The contractarian view of the state suggests that states form because people can all benefit from cooperation with others[26] and that without a state there would be chaos.[27] The contractarian view focuses more on the alignment and conflict of interests between individuals in a state. On the other hand, the predatory view of the state focuses on the potential mismatch between the interests of the people and the interests of the state. Charles Tilly goes so far to say that states "resemble a form of organized crime and should be viewed as extortion rackets."[28] He argued that the state sells protection from itself and raises the question about why people should trust a state when they cannot trust one another.[23] Tilly defines states as "coercion-wielding organisations that are distinct from households and kinship groups and exercise a clear priority in some respects over all other organizations within substantial territories."[29] Tilly includes city-states, theocracies and empires in his definition along with nation-states, but excludes tribes, lineages, firms and churches.[30] According to Tilly, states can be seen in the archaeological record as of 6000 BC; in Europe they appeared around 990, but became particularly prominent after 1490.[30] Tilly defines a state's "essential minimal activities" as: 1. War making – "eliminating or neutralizing their outside rivals" 2. State making – "eliminating or neutralizing their rivals inside their own territory" 3. Protection – "eliminating or neutralizing the enemies of their clients" 4. Extraction – "acquiring the means of carrying out the first three activities" 5. Adjudication – "authoritative settlement of disputes among members of the population" 6. Distribution – "intervention in the allocation of goods among the members of the population" 7. Production – "control of the creation and transformation of goods and services produced by the population"[31][32] 8. Importantly, Tilly makes the case that war is an essential part of state-making; that wars create states and vice versa.[33] Modern academic definitions of the state frequently include the criterion that a state has to be recognized as such by the international community.[34] Liberal thought provides another possible teleology of the state. According to John Locke, the goal of the state or commonwealth is "the preservation of property" (Second Treatise on Government), with 'property' in Locke's work referring not only to personal possessions but also to one's life and liberty. On this account, the state provides the basis for social cohesion and productivity, creating incentives for wealth-creation by providing guarantees of protection for one's life, liberty and personal property. Provision of public goods is considered by some such as Adam Smith[35] as a central function of the state, since these goods would otherwise be underprovided. Tilly has challenged narratives of the state as being the result of a societal contract or provision of services in a free market – he characterizes the state more akin as a protection racket in the vein of organized crime.[32] While economic and political philosophers have contested the monopolistic tendency of states,[36] Robert Nozick argues that the use of force naturally tends towards monopoly.[37] Another commonly accepted definition of the state is the one given at the Montevideo Convention on the Rights and Duties of States in 1933. It provides that "[t]he state as a person of international law should possess the following qualifications: (a) a permanent population; (b) a defined territory; (c) government; and (d) capacity to enter into relations with the other states."[38] And that "[t]he federal state shall constitute a sole person in the eyes of international law."[39] Confounding the definition problem is that "state" and "government" are often used as synonyms in common conversation and even some academic discourse. According to this definition schema, the states are nonphysical persons of international law, and governments are organizations of people.[40] The relationship between a government and its state is one of representation and authorized agency.[41] |

定義 国家の定義について学術的な合意は存在しない。[6] 「国家」という用語は、特定の範囲の政治現象に関する、異なるが相互に関連し、しばしば重複する一連の理論を指す. [7] ウォルター・シャイデルによれば、国家の主流的な定義には以下の共通点がある。「領土的に限定された住民に対して規則を課し、それを武力によって裏付ける 中央集権的な制度、支配者と被支配者の区別、そして自律性、安定性、差別化の要素である。これらは、首長の権力行使など、より不安定な組織形態と国家を区 別するものである」[16]。 最も一般的に使用される定義は、マックス・ヴェーバーによるものである[17][18][19][20][21]。彼は、国家を、特定の領域内で合法的な 武力の行使を独占する中央集権的な政府を持つ強制的な政治組織と定義している[8][9]。ヴェーバーは、国家とは「特定の領域内で物理的な武力の合法的 な行使の独占を(成功裏に)主張する人間共同体」であると述べている。[22] 国家を定義する上で、国家と国民を混同しないことが重要だ。これは一般的な議論で頻繁に起こる誤りである。国家とは、特定の領土に対する主権を持つ政治単 位を指す。[23] 国民は「政治的・法的な抽象概念」であるのに対し、国民という定義は、政治的アイデンティティや文化的・歴史的要因により関わるものである。[23] 重要なことは、国民は、国家が持つような地理的境界や権威者、役人といった組織的特徴を持たないということである。[23] さらに、国民は、その国民に対する合法的な武力行使の独占権を主張することはできないが、ヴェーバーが指摘したように、国家はそれを主張することができ る。[23] 国家が武力の行使を独占していない場合に生じる不安定性の例としては、ヨーロッパ諸国が依存していた戦争がないために弱体なままであるアフリカ諸国が挙げ られる。[24] 国家は政府と混同すべきではない。政府は、国家に代わって行動する権限を与えられた組織である。[23] また、国家を社会と混同すべきではない。社会とは、国家から独立し、その影響力を受けないように努める、あらゆる組織化された集団、運動、個人を指すもの である。[23] ノイバーガーは、国家と国民に関して、国家の定義を少し異なる形で提示している。国家とは、「特定の[国民]の才能の、根源的、本質的、かつ永続的な表現」である。[25] 国家の定義は、その形成過程や理由にも依存する。契約論的国家観によれば、国家は人民が相互協力から利益を得られるため形成され[26]、国家がなければ 混乱が生じる[27]とされる。この見解は国家内の個人間における利害の一致と対立に焦点を当てる。一方、国家の略奪的見解は、人民の利益と国家の利益の 潜在的な不一致に焦点を当てる。チャールズ・ティリーは国家を「組織犯罪の一形態に似ており、恐喝組織と見なすべきだ」とまで述べている[28]。彼は国 家が自らからの保護を売り物にしていると主張し、互いを信頼できない人々がなぜ国家を信頼すべきなのかという疑問を提起した。[23] ティリーは国家を「家内や親族集団とは区別され、広大な領域内の他のあらゆる組織に対して明確な優先権を行使する、強制力を行使する組織体」と定義する [29]。この定義には都市国家、神権政治、帝国が包含されるが、部族、氏族、企業、教会は除外される。[30] ティリーによれば、国家は紀元前6000年頃の考古学的記録に確認できる。ヨーロッパでは990年頃に現れたが、1490年以降に特に顕著になった [30]。ティリーは国家の「本質的最小活動」を以下のように定義する: 1. 戦争遂行 – 「外部ライバルの排除または無力化」 2. 国家形成 – 「自領内のライバルを消去法または無力化すること」 3. 保護 – 「被保護者の敵を消去法または無力化すること」 4. 搾取 – 「上記三つの活動を行う手段を獲得すること」 5. 裁定 – 「住民間の紛争を権威をもって解決すること」 6. 分配 – 「住民間の財分配への介入」 7. 生産 – 「住民が生み出す財・サービスの創造と変容の統制」[31][32] 8. 重要な点として、ティリーは戦争が国家形成の本質的要素であり、戦争が国家を生み出し、国家が戦争を生み出すと論じる。[33] 現代の国家に関する学術的定義では、国家が国際社会からそのように認められる必要があるという基準が頻繁に含まれる。[34] 自由主義思想は国家の別の目的論を提供する。ジョン・ロックによれば、国家または共和国の目的は「財産の保全」である(『政府論 第二篇』)。ロックの著作における「財産」は個人の所有物だけでなく、生命と自由も指す。この観点では、国家は社会結束と生産性の基盤を提供し、生命・自 由・人格の私有財産の保護を保証することで富創出のインセンティブを生む。アダム・スミスら[35]は公共財の提供を国家の中核機能とみなす。なぜなら、 国家が提供しなければ公共財は供給不足に陥るからだ。ティリーは、国家が社会契約や自由市場におけるサービス提供の結果であるとする通説に異議を唱えてい る。彼は国家を、むしろ組織犯罪的な保護料徴収組織に類似したものとして特徴づける[32]。 経済・政治思想家たちが国家の独占的傾向を批判してきた一方で[36]、ロバート・ノジックは、武力行使は本質的に独占へと向かう傾向があると主張する[37]。 国家のもう一つの一般的な定義は、1933年のモンテビデオ条約(国家の権利と義務に関する条約)で示されたものだ。そこでは「国際法上の人格としての国 家は、以下の要件を備えるべきである:(a)恒常的な住民、(b)明確な領土、(c)政府、(d)他国と関係を樹立する能力」と規定されている[38]。 また「連邦国家は国際法上単一の人格を構成する」とも規定している[39]。 この定義問題をさらに複雑にしているのは、「国家」と「政府」が日常会話や一部の学術的言説においてしばしば同義語として用いられることだ。この定義体系 によれば、国家は非物理的な国際法上の人格であり、政府は人民の組織である[40]。政府とその国家との関係は、代表関係および授権された代理関係である [41]。 |

| Types of states Charles Tilly distinguished between empires, theocracies, city-states and nation-states.[30] According to Michael Mann, the four persistent types of state activities are: 1. Maintenance of internal order 2. Military defence and aggression 3. Maintenance of communications infrastructure 4. Economic redistribution[42] Josep Colomer distinguished between empires and states in the following way: 1. Empires were vastly larger than states 2. Empires lacked fixed or permanent boundaries whereas a state had fixed boundaries 3. Empires had a "compound of diverse groups and territorial units with asymmetric links with the center" whereas a state had "supreme authority over a territory and population" 4. Empires had multi-level, overlapping jurisdictions whereas a state sought monopoly and homogenization[43] According to Michael Hechter and William Brustein, the modern state was differentiated from "leagues of independent cities, empires, federations held together by loose central control, and theocratic federations" by four characteristics: 1. The modern state sought and achieved territorial expansion and consolidation 2. The modern state achieved unprecedented control over social, economic, and cultural activities within its boundaries 3. The modern state established ruling institutions that were separate from other institutions 4. The ruler of the modern state was far better at monopolizing the means of violence[44] States may be classified by political philosophers as sovereign if they are not dependent on, or subject to any other power or state. Other states are subject to external sovereignty or hegemony where ultimate sovereignty lies in another state.[45] Many states are federated states which participate in a federal union. A federated state is a territorial and constitutional community forming part of a federation.[46] (Compare confederacies or confederations such as Switzerland.) Such states differ from sovereign states in that they have transferred a portion of their sovereign powers to a federal government.[47] One can commonly and sometimes readily (but not necessarily usefully) classify states according to their apparent make-up or focus. The concept of the nation-state, theoretically or ideally co-terminous with a "nation", became very popular by the 20th century in Europe, but occurred rarely elsewhere or at other times. In contrast, some states have sought to make a virtue of their multi-ethnic or multinational character (Habsburg Austria-Hungary, for example, or the Soviet Union), and have emphasised unifying characteristics such as autocracy, monarchical legitimacy, or ideology. Other states, often fascist or authoritarian ones, promoted state-sanctioned notions of racial superiority.[48] Other states may bring ideas of commonality and inclusiveness to the fore: note the res publica of ancient Rome and the Rzeczpospolita of Poland-Lithuania which finds echoes in the modern-day republic. The concept of temple states centred on religious shrines occurs in some discussions of the ancient world.[49] Relatively small city-states, once a relatively common and often successful form of polity,[50] have become rarer and comparatively less prominent in modern times. Modern-day independent city-states include Vatican City, Monaco, and Singapore. Other city-states survive as federated states, like the present day German city-states, or as otherwise autonomous entities with limited sovereignty, like Hong Kong, Gibraltar and Ceuta. To some extent, urban secession, the creation of a new city-state (sovereign or federated), continues to be discussed in the early 21st century in cities such as London. |

国家の類型 チャールズ・ティリーは帝国、神権政治国家、都市国家、国民国家を区別した[30]。マイケル・マンによれば、国家活動における四つの持続的類型は次の通りである: 1. 内部秩序の維持 2. 軍事的防衛と侵略 3. 通信インフラの維持 4. 経済的再分配[42] ホセップ・コロメルは帝国と国家を次のように区別した: 1. 帝国は国家よりもはるかに広大であった 2. 帝国には固定された恒久的な境界がなかったが、国家には固定された境界があった 3. 帝国は「中心部との非対称的な結びつきを持つ多様な集団と領土単位の集合体」であったが、国家は「領土と人口に対する最高権威」を有していた 4. 帝国は多層的で重複する管轄権を持つが、国家は独占と均質化を追求する[43] マイケル・ヘクターとウィリアム・ブルスタインによれば、近代国家は「独立都市同盟、帝国、緩やかな中央統制で結ばれた連邦、神権的連邦」と四つの特徴で区別される: 1. 現代国家は領土の拡張と統合を追求し達成した 2. 現代国家は自国領域内の社会的・経済的・文化的活動に対し前例のない統制を確立した 3. 現代国家は他の制度から分離された統治機構を確立した 4. 現代国家の統治者は暴力の手段を独占する能力が格段に優れていた[44] 政治哲学者によれば、国家は他の権力や国家に依存せず従属しない場合、主権国家と分類される。他の国家は外部主権またはヘゲモニー下にあり、究極的な主権 は別の国家に帰属する[45]。多くの国家は連邦国家であり、連邦連合に参加している。連邦国家とは、連邦を構成する一部をなす領土的・憲法上の共同体で ある[46](スイスなどの連合体や連合国家と比較せよ)。こうした国家は、主権国家とは異なり、主権の一部を連邦政府に移譲している。[47] 国民は、その表向きの構成や焦点に基づいて、一般的に、時には容易に(ただし必ずしも有益とは限らないが)分類できる。理論上あるいは理想的には「国民」 と一致する国民国家の概念は、20世紀のヨーロッパで非常に普及したが、他の地域や時代では稀であった。これに対し、多民族・多国籍的性格を美徳として強 調した国家もある(ハプスブルク家のオーストリア=ハンガリー帝国やソビエト連邦など)。また、専制政治、君主制の正当性、イデオロギーといった統合的特 性を重視した例もある。また、ファシズムや権威主義国家では、国家が公認する人種的優越性の概念を推進した[48]。さらに、共通性や包摂性の理念を前面 に出す国家もある。古代ローマの「共和制(res publica)」や、現代の共和国にも響きを持つポーランド・リトアニア共和国の「共和国(Rzeczpospolita)」がそれにあたる。宗教的聖 堂を中心とする神殿国家の概念は、古代世界に関する議論で時折見られる[49]。比較的小規模な都市国家は、かつては比較的普遍的でしばしば成功した政治 形態だったが[50]、現代ではより稀になり、相対的に目立たなくなった。現代の独立都市国家にはバチカン市国、モナコ、シンガポールがある。その他の都 市国家は、現在のドイツの都市国家のように連邦構成州として、あるいは香港、ジブラルタル、セウタのように限定された主権を持つ自治体として存続してい る。ある程度、都市分離独立、すなわち新たな都市国家(主権国家または連邦構成州)の創設は、21世紀初頭のロンドンなどの都市において議論され続けてい る。 |

| State and government See also: Government A state can be distinguished from a government. The state is the organization while the government is the particular group of people, the administrative bureaucracy that controls the state apparatus at a given time.[51][52][53] That is, governments are the means through which state power is employed. States are served by a continuous succession of different governments.[53] States are immaterial and nonphysical social objects, whereas governments are groups of people with certain coercive powers.[54] Each successive government is composed of a specialized and privileged body of individuals, who monopolize political decision-making and are separated by status and organization from the population as a whole. States and nation-states See also: Nation state States can also be distinguished from the concept of a "nation", where "nation" refers to a cultural-political community of people. A nation-state refers to a situation where a single ethnicity is associated with a specific state. State and civil society In the classical thought, the state was identified with both political society and civil society as a form of political community, while the modern thought distinguished the nation state as a political society from civil society as a form of economic society.[55] Thus in the modern thought the state is contrasted with civil society.[56][57][58] Antonio Gramsci believed that civil society is the primary locus of political activity because it is where all forms of "identity formation, ideological struggle, the activities of intellectuals, and the construction of hegemony take place." and that civil society was the nexus connecting the economic and political sphere. Arising out of the collective actions of civil society is what Gramsci calls "political society", which Gramsci differentiates from the notion of the state as a polity. He stated that politics was not a "one-way process of political management" but, rather, that the activities of civil organizations conditioned the activities of political parties and state institutions, and were conditioned by them in turn.[59][60] Louis Althusser argued that civil organizations such as church, schools, and the family are part of an "ideological state apparatus" which complements the "repressive state apparatus" (such as police and military) in reproducing social relations.[61][62][63] Jürgen Habermas spoke of a public sphere that was distinct from both the economic and political sphere.[64] Given the role that many social groups have in the development of public policy and the extensive connections between state bureaucracies and other institutions, it has become increasingly difficult to identify the boundaries of the state. Privatization, nationalization, and the creation of new regulatory bodies also change the boundaries of the state in relation to society. Often the nature of quasi-autonomous organizations is unclear, generating debate among political scientists on whether they are part of the state or civil society. Some political scientists thus prefer to speak of policy networks and decentralized governance in modern societies rather than of state bureaucracies and direct state control over policy.[65] |

国家と政府 関連項目: 政府 国家は政府と区別できる。国家は組織体であり、政府は特定の集団、すなわち特定の時期に国家機構を支配する行政官僚機構である。[51][52] [53] つまり政府とは、国家権力を行使する手段である。国家は、異なる政府が絶え間なく交代しながら奉仕される。[53] 国家は非物質的・非物理的な社会的対象であるのに対し、政府は特定の強制力を有する人民の集団である。[54] 各々の政府は、専門的で特権的な個人の集団から構成される。彼らは政治的意思決定を独占し、地位と組織によって一般大衆から隔てられている。 国家と国民国家 関連項目:国民国家 国家は「国民」という概念とも区別される。「国民」とは文化的・政治的な共同体を指す。国民国家とは、単一の民族が特定の国家と結びついた状態を指す。 国家と市民社会 古典的思考においては、国家は政治共同体としての政治社会と市民社会の両方と同一視されていた。一方、近代的思考では、政治社会としての国民国家と経済社会としての市民社会が区別されるようになった。[55] したがって近代思想において国家は市民社会と対比される。[56][57][58] アントニオ・グラムシは、市民社会こそが政治活動の主要な場であると主張した。なぜならそこではあらゆる形態の「アイデンティティ形成、イデオロギー闘 争、知識人の活動、ヘゲモニー構築」が行われるからである。また市民社会は経済圏と政治圏を結ぶ接点であると述べた。市民社会の集団的行動から生じるもの を、グラムシは「政治社会」と呼んだ。これは国家という政治共同体(ポリティ)の概念とは区別される。彼は政治を「政治的管理の一方通行プロセス」ではな く、市民組織の活動が政党や国家機関の活動を条件付け、逆にそれらから条件付けられる相互作用と定義した。[59][60] ルイ・アルチュセールは、教会・学校・家族などの市民組織が「抑圧的国家装置」(警察・軍隊など)を補完し、社会関係を再生産する「イデオロギー的国家装 置」の一部だと論じた。[61][62] [63] ユルゲン・ハーバーマスは、経済圏や政治圏とは異なる公共圏について論じた。[64] 多くの社会集団が公共政策の形成に果たす役割や、国家官僚機構と他機関との広範な繋がりを考慮すると、国家の境界を特定することはますます困難になってい る。民営化、国民化、新たな規制機関の創設もまた、社会との関係における国家の境界を変える。準自律的組織の性質はしばしば不明確であり、それらが国家の 一部なのか市民社会の一部なのかについて政治学者間で議論を生んでいる。したがって一部の政治学者は、現代社会においては国家官僚機構や政策に対する直接 的な国家統制というよりも、政策ネットワークや分散型ガバナンスについて論じることを好むのである。[65] |

| State symbols See also: National symbol flag coat of arms or national emblem seal or stamp national motto national colors national anthem |

国民の象徴 関連項目:国家の象徴 国旗 紋章または国家の紋章 印章またはスタンプ 国家の標語 国家の色彩 国歌 |

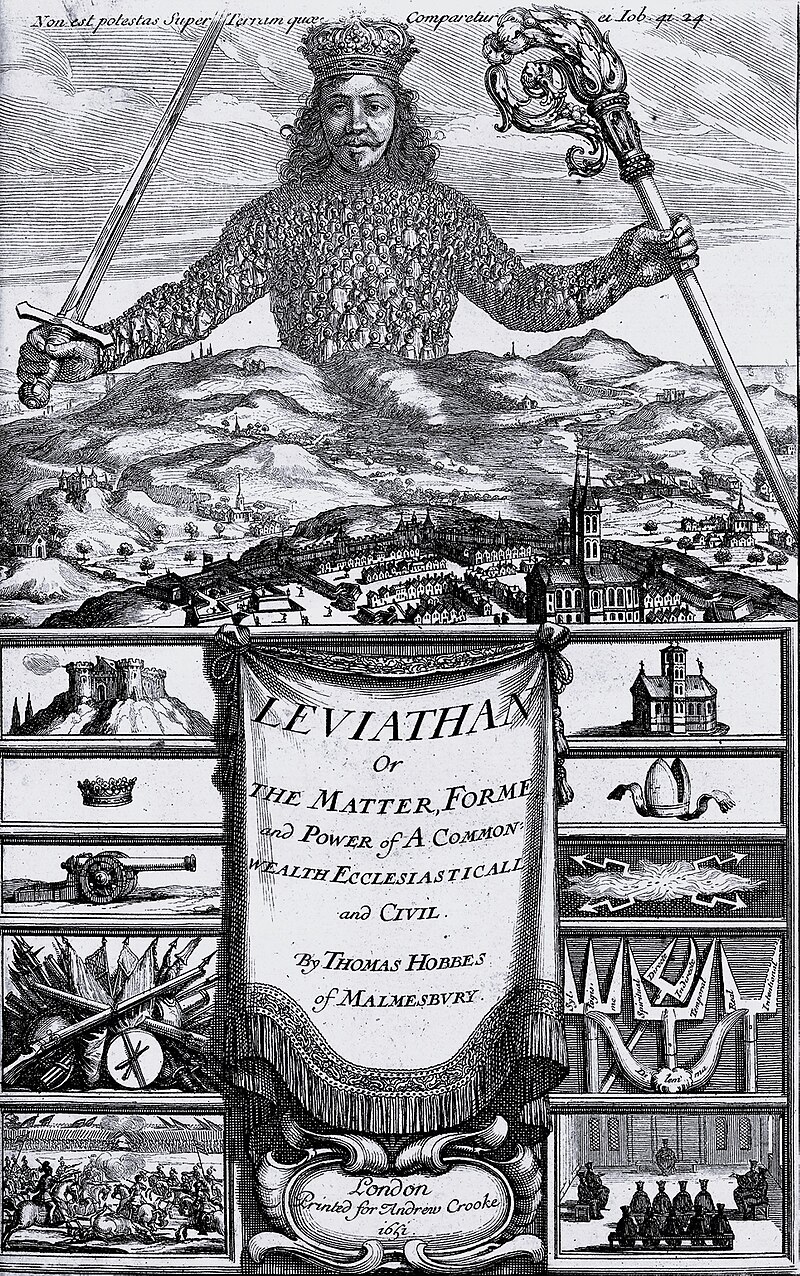

History The frontispiece of Thomas Hobbes' Leviathan The earliest forms of the state emerged whenever it became possible to centralize power in a durable way. Agriculture and a settled population have been attributed as necessary conditions to form states.[66][67][68][69] Certain types of agriculture are more conducive to state formation, such as grain (wheat, barley, millet), because they are suited to concentrated production, taxation, and storage.[66][70][71][72] Agriculture and writing are almost everywhere associated with this process: agriculture because it allowed for the emergence of a social class of people who did not have to spend most of their time providing for their own subsistence, and writing (or an equivalent of writing, like Inca quipus) because it made possible the centralization of vital information.[73] Bureaucratization made expansion over large territories possible.[74] The first known states were created in Egypt, Mesopotamia, India, China, Mesoamerica, and the Andes. It is only in relatively modern times that states have almost completely displaced alternative "stateless" forms of political organization of societies all over the planet. Roving bands of hunter-gatherers and even fairly sizable and complex tribal societies based on herding or agriculture have existed without any full-time specialized state organization, and these "stateless" forms of political organization have in fact prevailed for all of the prehistory and much of human history and civilization. The primary competing organizational forms to the state were religious organizations (such as the Church), and city republics.[75] Since the late 19th century, virtually the entirety of the world's inhabitable land has been parcelled up into areas with more or less definite borders claimed by various states. Earlier, quite large land areas had been either unclaimed or uninhabited, or inhabited by nomadic peoples who were not organised as states. However, even within present-day states there are vast areas of wilderness, like the Amazon rainforest, which are uninhabited or inhabited solely or mostly by indigenous people (and some of them remain uncontacted). Also, there are so-called "failed states" which do not hold de facto control over all of their claimed territory or where this control is challenged. The international community comprises around 200 sovereign states, the vast majority of which are represented in the United Nations.[76] |

歴史 トマス・ホッブズの『リヴァイアサン』の扉絵 国家の最も初期の形態は、権力を永続的な方法で集中させることが可能になった時に現れた。国家形成には農業と定住人口が必須条件とされる[66][67] [68][69]。穀物(小麦、大麦、キビ)のような特定の農業形態は、集中生産・課税・貯蔵に適しているため、国家形成をより促進する[66]。 [70][71][72] 農業と文字はほぼどこでもこの過程と結びついている。農業は、自らの生計維持に大半の時間を費やす必要のない社会階層の出現を可能にしたからであり、文字 (あるいはインカのキプスのような文字に相当するもの)は、重要な情報の中央集権化を可能にしたからである。[73] 官僚制化は広大な領域への拡大を可能にした。[74] 最初に知られている国家は、エジプト、メソポタミア、インド、中国、メソアメリカ、アンデスで成立した。国家が地球上のあらゆる社会の政治組織における代 替的な「無国家」形態をほぼ完全に駆逐したのは、比較的近代になってからのことである。狩猟採集民の遊牧集団や、群畜や農業を基盤とするかなり大規模で複 雑な部族社会でさえ、常設の専門的な国家機構なしに存在してきた。そしてこうした「国家を持たない」形態の政治組織は、実際には先史時代全体と人類の歴 史・文明の大部分において主流であった。 国家と競合した主要な組織形態は、宗教組織(教会など)と都市共和国であった。[75] 19世紀後半以降、世界の居住可能地域のほぼ全域が、様々な国家によって主張される、多かれ少なかれ明確な境界を持つ領域に分割されてきた。それ以前に は、非常に広大な土地が未領有か無人地帯であったか、あるいは国家として組織化されていない遊牧民によって居住されていた。しかし、現在の国家内にもアマ ゾン熱帯雨林のような広大な未開地域が存在し、これらは無人地帯であるか、先住民のみ(あるいは主に先住民)が居住している(その一部は未接触のままであ る)。また、自国が主張する領土全体を事実上支配できていない、あるいはその支配が争われている、いわゆる「失敗国家」も存在する。国際社会は約200の 主権国家で構成されており、その大部分は国連に加盟している。[76] |

| Prehistoric stateless societies Main article: Stateless societies For most of human history, people have lived in stateless societies, characterized by a lack of concentrated authority, and the absence of large inequalities in economic and political power. The anthropologist Tim Ingold writes: It is not enough to observe, in a now rather dated anthropological idiom, that hunter gatherers live in 'stateless societies', as though their social lives were somehow lacking or unfinished, waiting to be completed by the evolutionary development of a state apparatus. Rather, the principal of their socialty, as Pierre Clastres has put it, is fundamentally against the state.[77] |

先史時代の国家を持たない社会 主な記事: 国家を持たない社会 人類史の大部分において、人民は国家を持たない社会で暮らしてきた。そこでは権力が集中せず、経済的・政治的権力における大きな格差も存在しなかった。 人類学者ティム・インゴールドはこう記している: 狩猟採集民が「国家のない社会」に生きていると、今ややや時代遅れとなった人類学の慣用句で観察するだけでは不十分だ。あたかも彼らの社会生活が何か欠け ているか未完成であり、国家機構の進化的発展によって完成されるのを待っているかのように。むしろ、ピエール・クラストルが述べたように、彼らの社会性の 原理は根本的に国家に反対するものである。[77] |

| Neolithic period Further information: Neolithic and Copper Age state societies During the Neolithic period, human societies underwent major cultural and economic changes, including the development of agriculture, the formation of sedentary societies and fixed settlements, increasing population densities, and the use of pottery and more complex tools.[78][79] Sedentary agriculture led to the development of property rights, domestication of plants and animals, and larger family sizes. It also provided the basis for an external centralized state.[80] By producing a large surplus of food, more division of labor was realized, which enabled people to specialize in tasks other than food production.[81] Early states were characterized by highly stratified societies, with a privileged and wealthy ruling class that was subordinate to a monarch. The ruling classes began to differentiate themselves through forms of architecture and other cultural practices that were different from those of the subordinate laboring classes.[82] In the past, it was suggested that the centralized state was developed to administer large public works systems (such as irrigation systems) and to regulate complex economies.[83] However, modern archaeological and anthropological evidence does not support this thesis, pointing to the existence of several non-stratified and politically decentralized complex societies.[84] |

新石器時代 詳細情報:新石器時代および銅器時代の国家社会 新石器時代において、人類社会は農業の発展、定住社会と固定集落の形成、人口密度の増加、陶器やより複雑な道具の使用など、文化的・経済的に大きな変化を経験した。[78][79] 定住農業は財産権の発展、動植物の家畜化、家族規模の拡大をもたらした。また、外部的な中央集権国家の基盤も提供した。[80] 食糧の大量余剰を生み出すことで、より多くの分業が実現され、人々は食糧生産以外の業務に特化できるようになった。[81] 初期国家は高度に階層化された社会を特徴とし、君主に従属する特権的で富裕な支配階級が存在した。支配階級は、従属的な労働者階級とは異なる建築様式やそ の他の文化的慣行を通じて、自らの差別化を図り始めた。[82] かつては、中央集権国家は(灌漑システムなどの)大規模公共事業システムを管理し、複雑な経済を規制するために発展したと考えられていた。[83] しかし、現代の考古学的・人類学的証拠はこの説を支持せず、階層化されておらず政治的に分散した複数の複雑な社会が存在したことを示している。[84] |

| Ancient Eurasia See also: Mesopotamia, Ancient Egypt, Indus Valley Civilization, and Yellow River civilization Mesopotamia is generally considered to be the location of the earliest civilization or complex society, meaning that it contained cities, full-time division of labor, social concentration of wealth into capital, unequal distribution of wealth, ruling classes, community ties based on residency rather than kinship, long distance trade, monumental architecture, standardized forms of art and culture, writing, and mathematics and science.[85][86] It was the world's first literate civilization, and formed the first sets of written laws.[87][88] Bronze metallurgy spread within Afro-Eurasia from c. 3000 BC, leading to a military revolution in the use of bronze weaponry, which facilitated the rise of states.[89] |

古代ユーラシア 関連項目:メソポタミア、古代エジプト、インダス文明、黄河文明 メソポタミアは、一般的に最も初期の文明または複雑な社会の発生地と見なされている。つまり、都市、専門分業、富の資本への集中、富の不平等な分配、支配 階級、血縁ではなく居住に基づく共同体関係、長距離貿易、記念碑的建築、標準化された芸術文化、文字、数学と科学を備えていた。[85][86] これは世界初の文字文明であり、最初の成文法の体系を形成した。[87][88] 青銅器技術は紀元前3000年頃からアフロ・ユーラシア地域に広がり、青銅武器の使用による軍事革命をもたらした。これが国家の興隆を促進したのである。 [89] |

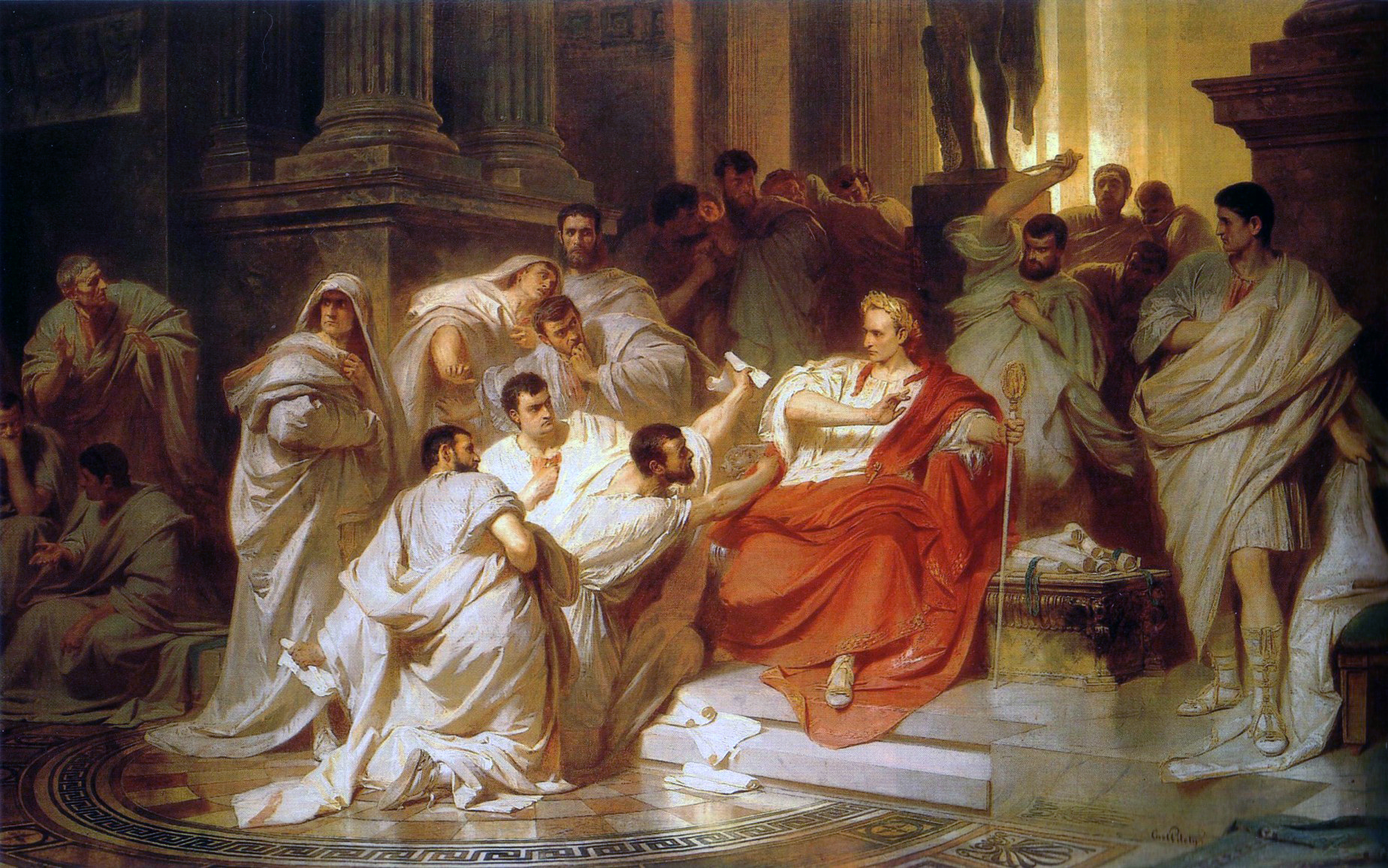

| Classical antiquity See also: Athenian democracy and Roman Republic  Painting of Roman Senators encircling Julius Caesar Although state-forms existed before the rise of the Ancient Greek empire, the Greeks were the first people known to have explicitly formulated a political philosophy of the state, and to have rationally analyzed political institutions. Prior to this, states were described and justified in terms of religious myths.[90] Several important political innovations of classical antiquity came from the Greek city-states and the Roman Republic. The Greek city-states before the 4th century granted citizenship rights to their free population, and in Athens these rights were combined with a directly democratic form of government that was to have a long afterlife in political thought and history. |

古典古代 関連項目: アテネ民主制とローマ共和国  ユリウス・カエサルを取り囲むローマ元老院議員の絵画 古代ギリシャ帝国の台頭以前に国家形態は存在したが、国家に関する政治哲学を明確に体系化し、政治制度を理性的に分析した最初の人民はギリシャ人であった。それ以前には、国家は宗教的神話によって説明され正当化されていた。[90] 古典古代におけるいくつかの重要な政治的革新は、ギリシャの都市国家とローマ共和政から生まれた。紀元前4世紀以前のギリシャの都市国家は、自由民に市民 権を認めていた。アテネでは、この権利が直接民主制という政治形態と結びつき、政治思想と歴史において長く影響を及ぼすこととなった。 |

| Feudal state See also: Feudalism and Middle Ages During medieval times in Europe, the state was organized on the principle of feudalism, and the relationship between lord and vassal became central to social organization. Feudalism led to the development of greater social hierarchies.[91] The formalization of the struggles over taxation between the monarch and other elements of society (especially the nobility and the cities) gave rise to what is now called the Standestaat, or the state of Estates, characterized by parliaments in which key social groups negotiated with the king about legal and economic matters. These estates of the realm sometimes evolved in the direction of fully-fledged parliaments, but sometimes lost out in their struggles with the monarch, leading to greater centralization of lawmaking and military power in his hands. Beginning in the 15th century, this centralizing process gave rise to the absolutist state.[92] |

封建国家 関連項目: 封建制度と中世 中世ヨーロッパにおいて、国家は封建制度の原則に基づいて組織され、領主と家臣の関係が社会組織の中心となった。封建制度はより大きな社会階層の発展をもたらした。[91] 君主と社会諸勢力(特に貴族や都市)との間の課税を巡る争いが形式化することで、いわゆる「三部会国家」が生まれた。これは主要な社会集団が議会において 国王と法的・経済的問題を交渉する特徴を持つ。これらの三部会は完全な議会へと発展する場合もあれば、君主との争いで敗れ、立法権と軍事力が君主の手中に 集中する結果となる場合もあった。15世紀以降、この中央集権化のプロセスが絶対主義国家を生み出したのである。[92] |

| Modern state See also: Bureaucracy, Constitution, Corporation, Globalization, and Neoliberalism Cultural and national homogenization figured prominently in the rise of the modern state system. Since the absolutist period, states have largely been organized on a national basis. The concept of a national state, however, is not synonymous with nation state. Even in the most ethnically homogeneous societies there is not always a complete correspondence between state and nation, hence the active role often taken by the state to promote nationalism through an emphasis on shared symbols and national identity.[93] Charles Tilly argues that the number of total states in Western Europe declined rapidly from the Late Middle Ages to Early Modern Era during a process of state formation.[94] Other research has disputed whether such a decline took place.[95] For Edmund Burke (Dublin 1729 - Beaconsfield 1797), "a state without the means of some change is without the means of its conservation" (Reflections on the Revolution in France).[96] According to Hendrik Spruyt, the modern state is different from its predecessor polities in two main aspects: (1) Modern states have a greater capacity to intervene in their societies, and (2) Modern states are buttressed by the principle of international legal sovereignty and the judicial equivalence of states.[97] The two features began to emerge in the Late Middle Ages but the modern state form took centuries to come firmly into fruition.[97] Other aspects of modern states is that they tend to be organized as unified national polities, and that they have rational-legal bureaucracies.[98] Sovereign equality did not become fully global until after World War II amid decolonization.[97] Adom Getachew writes that it was not until the 1960 Declaration on the Granting of Independence to Colonial Countries and Peoples that the international legal context for popular sovereignty was instituted.[99] Historians Jane Burbank and Frederick Cooper argue that "Westphalian sovereignty" – the notion that bounded, unitary states interact with equivalent states – "has more to do with 1948 than 1648."[100] |

近代国家 関連項目:官僚制、憲法、企業、グローバリゼーション、新自由主義 近代国家システムの台頭において、文化的・国民的均質化は顕著な役割を果たした。絶対主義時代以降、国家は主に国民的基盤に基づいて組織されてきた。しか し国民国家の概念は、国民国家と同義ではない。最も民族的に均質な社会でさえ、国家と国民国家が完全に一致するとは限らない。そのため国家は、共有の象徴 や国民的アイデンティティを強調することでナショナリズムを促進する積極的な役割を担うことが多いのである。[93] チャールズ・ティリーは、国家形成の過程において、西ヨーロッパの国家総数が中世後期から近世初期にかけて急速に減少したと主張している。[94] 他の研究では、そのような減少が実際に起こったかどうかについて異論が唱えられている。[95] エドマンド・バーク(1729年ダブリン生まれ - 1797年ビーコンズフィールド没)によれば、「変化の手段を持たない国家は、その存続の手段を持たない」(『フランス革命に関する省察』)。[96] ヘンドリック・スプルートによれば、近代国家は先行する政治体制と主に二点で異なる:(1) 近代国家は社会への介入能力がより高いこと、(2) 国際法上の主権原則と国家間の司法的等価性によって支えられていることである。[97] これらの特徴は中世後期に現れ始めたが、近代国家形態が確固たる形で確立するには数世紀を要した。[97] 近代国家の他の側面として、統一された国民として組織化される傾向があり、合理的・法的な官僚機構を有することが挙げられる。[98] 主権平等は、第二次世界大戦後の脱植民地化の中で、初めて完全に世界的なものとなった。[97] アドム・ゲタチューは、1960年の「植民地国および人民の独立の付与に関する宣言」によって、初めて人民主権に関する国際的な法的枠組みが確立されたと 記している。[99] 歴史家のジェーン・バーバンクとフレデリック・クーパーは、「ウェストファリア的主権」、つまり、境界のある単一国家が同等の国家と交流するという概念 は、「1648年よりも1948年とより深く関係している」と主張している。[100] |

| Theories for the emergence of the state Earliest states Theories for the emergence of the earliest states emphasize grain agriculture and settled populations as necessary conditions.[86] However, not all types of property are equally exposed to the risk of looting or equally subject to taxation. Goods differ in their shelf life. Certain agricultural products, fish, and dairy spoil quickly and cannot be stored without refrigeration or freezing technology, which was unavailable in ancient times. As a result, such perishable goods were of little interest to either looters or the king (In ancient times, especially before the invention of money, taxation was primarily collected from agricultural produce.) Both looters and rulers sought goods with long shelf lives, such as grains (wheat, barley, rice, corn, etc.), which, under proper storage conditions, could be preserved for extended periods. With the domestication of wheat and the establishment of agricultural communities, the need for protection from bandits arose, along with the emergence of strong governance to provide it. Mayshar et al. (2020) demonstrated that societies cultivating grains tended to develop hierarchical structures with a ruling elite that collected taxes, whereas societies that relied on root crops (which have short shelf lives) did not develop such hierarchies. The cultivation of grains became concentrated in regions with fertile soil, where grain production was more profitable than root crops, even after accounting for taxes imposed by rulers and raids by looters.[101] However, protection was not the only public good necessitating a centralized government. The shift to agriculture based on irrigation systems, as seen in ancient Egypt, required cooperation among farmers. An individual farmer could not control the floods from the Nile River alone. Managing the vast amounts of water during the annual floods and utilizing them efficiently allowed for a significant increase in agricultural yield, but this required an elaborate network of irrigation canals to distribute water efficiently across fields while minimizing waste.[102][103] Such a system exhibited characteristics of a natural monopoly, as its construction involved substantial fixed costs, making it a lucrative asset for the ruling elite. Bentzen, Kaarsen, and Wingender (2017) showed that in pre-modern societies, regions dependent on irrigation-intensive agriculture experienced higher levels of land inequality. The concentration of land and control over water resources strengthened elite power, enabling them to resist democratization in the modern era. Even today, countries that rely on irrigated agriculture tend to be less democratic than those relying on rain-fed farming.[104] Some argue that climate change led to a greater concentration of human populations around dwindling waterways.[86] |

国家の出現に関する諸説 最古の国家 最古の国家の出現に関する諸説は、穀物農業と定住人口を必要条件として強調している。[86] しかし、あらゆる種類の財産が略奪の危険に等しく晒されるわけでも、課税の対象となるわけでもない。物品は保存期間が異なる。特定の農産物、魚、乳製品は 腐敗が早く、冷蔵や冷凍技術なしでは保存できない。古代にはこうした技術は存在しなかった。結果として、こうした腐りやすい商品は略奪者にも王にもほとん ど関心が持たれなかった(古代、特に貨幣発明前は、課税は主に農産物から徴収されていた)。略奪者も支配者も、穀物(小麦、大麦、米、トウモロコシなど) のように保存期間が長く、適切な保管条件下で長期間保存可能な商品を求めた。小麦の栽培化と農業共同体の成立に伴い、盗賊からの保護が必要となり、それを 提供する強力な統治体制が出現した。Maysharら(2020)は、穀物を栽培する社会では、税を徴収する支配階層を伴う階層構造が発達する傾向がある 一方、保存期間の短い根菜類に依存する社会ではそのような階層構造が発達しなかったことを示した。穀物栽培は肥沃な土壌地域に集中した。支配者による課税 や略奪者の襲撃を考慮しても、穀物生産は根菜類よりも収益性が高かったのである[101]。 しかし、中央集権的な政府を必要とする公共財は保護だけではない。古代エジプトに見られる灌漑システムに基づく農業への移行は、農民間の協力を必要とし た。個々の農民が単独でナイル川の洪水を制御することは不可能だった。年次洪水時の膨大な水量を管理し効率的に利用することで農業生産量は大幅に増加した が、これを実現するには、無駄を最小限に抑えながら田畑全体に水を効率的に分配する複雑な灌漑用水路網が必要だった[102]。[103] このようなシステムは自然独占の特性を示していた。その建設には多額の固定費が伴い、支配階層にとって有利な資産となったからだ。Bentzen、 Kaarsen、Wingender(2017)は、前近代社会において灌漑農業に依存する地域ほど土地の不平等が深刻化することを示した。土地の集中と 水資源の支配は支配層の権力を強化し、近代における民主化への抵抗を可能にした。今日でさえ、灌漑農業に依存する国々は、天水農業に依存する国々よりも民 主化が進んでいない傾向がある。[104] 気候変動が減少する水辺への人口集中を加速させたと主張する者もいる。[86] |

| Modern state Hendrik Spruyt distinguishes between three prominent categories of explanations for the emergence of the modern state as a dominant polity: (1) Security-based explanations that emphasize the role of warfare, (2) Economy-based explanations that emphasize trade, property rights and capitalism as drivers behind state formation, and (3) Institutionalist theories that sees the state as an organizational form that is better able to resolve conflict and cooperation problems than competing political organizations.[97] According to Philip Gorski and Vivek Swaroop Sharma, the "neo-Darwinian" framework for the emergence of sovereign states is the dominant explanation in the scholarship.[105] The neo-Darwininian framework emphasizes how the modern state emerged as the dominant organizational form through natural selection and competition.[105] |

近代国家 ヘンドリック・スプルートは、支配的な政治体制としての近代国家の出現に関する説明を三つの主要なカテゴリーに分類している:(1) 戦争の役割を強調する安全保障に基づく説明、(2) 国家形成の推進力として貿易、財産権、資本主義を強調する経済に基づく説明、(3) 国家を、競合する政治組織よりも紛争や協力の問題を解決するのに適した組織形態と見なす制度主義理論である。[97] フィリップ・ゴルスキーとヴィヴェック・スワループ・シャルマによれば、主権国家の出現に関する「新ダーウィニズム的」枠組みが学界で主流の説明となって いる。[105] この枠組みは、自然淘汰と競争を通じて近代国家が支配的な組織形態として出現した過程を強調する。[105] |

| Theories of state function |

"Theories of state function"以下は、「国家」に記載しています |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/State_(polity) |

ここで多様な国家観をあげ、皆さんがどのような国家間をもっているのか、チェックしましょう。

| 野獣的国家 | beastly state |

トーマス・ホッブスのリヴァイアサンに代表される国家観です。国家は強制力を国民に誇示して、恐怖や暴

力を通して支配を貫徹します。国歌や国旗は、愛国=郷土(patria)のシンボルであり、それらのシンボルを通して国家は国民に対する従属を要求し、国

民は国家に対する忠誠を誓います。(→「国家は我々自身を形づくる」) 国民は国家との契約において、国民の自由の一部を担保にしてでも、国家において国民の身体を 保護してしてもらうことに合意しており、国家による合法的な暴力——警察や軍隊——を容認できるものとする。 |

| 夜警国家 |

night watcher state, Nachtwächterstaat |

こ の国家観の変奏が「夜警国家 night watchman state」です。ドイツのフェルディナント・ラッサール(Ferdinand Lassalle, 1825-1864)が、近代国家(ブルジョアの利益を守る)の役割を揶揄して表現したもので ある。つまり、夜警国家とは、外敵に対する防衛、国内治安の維持、そして最低限の福祉政策に国家機能を限定しする自由放任の国家観である。福祉国家の対概 念とされてきた。s |

| 福祉国家 |

welfare state |

1930年代の英国がナチスドイツの戦争国家に対抗して自国の国家を表

象した宣伝用語に由来

する。それが冷戦期に共産主義や全体主義国家に対する概念用語として洗練されていった。国民保険などに代表される社会福祉サービスを中心として民主主義を

維 持するという国家運営形態を理想としている。 したがって福祉国家論はルーツとしてはナショナリズムから出発し、制度を含めた諸概念の発達 は反共産主義な後期資本主義的国家(マルクス主義的な批判用語では「国家独占資本主義期の国家形態」)においてなされた。 |

| 搾取的国家 |

Exploited state |

国家はおしなべて国民の利益を蹂躙し、すきあらば国民から搾取をおこなうものとみなされる。国民にとっては、国家のこのような不道徳に対して常に警戒し、場合によっては、国家にとって反乱し、暴力をもって国家の主宰者を権力から引き下ろす権 利を有すると考える。 したがって国家は、そのような暴力が暴発しないように、国民の福祉を謳い、そのような暴発が おこらないように、ソフトに管理しようとする。 |

| 人民的国家 |

People's state |

野獣的国家観における国家と国民が同じものであるとき、国家は国民の持

ち物になり、国民は国

家と同一視されます。国家は眼にみえる実体つまり郷土(patria)などを強力なシンボルとして動員して、国民管理をおしすすめます。かつての共産主義

国家はこのようなシステムを極度に押し進めました。国民どうしを、身分制を超えて〈同志〉としてお互いに呼び慣わすやり方は、宗教共同体における〈兄弟=

姉妹〉とおなじように、情念に裏付けられたつよい精神的共同体性をメンバーに押しつけます。 |

| 多元的国家観 |

多元的国家における多元とは、国家を構成する諸団体の多元的共存状態の

ことをさす。つまり、

自由主義にもとづく利害諸団体の調整が、国家の役割である。国家は、多様な目的をもつ、それらの団体の調整に熱意を注ぐことに、民主主義の存在意味を見い

だす。したがって、この社会の経済システムは新古典派経済学を軸とする自由主義経済である。経済のグローバル化に対しては、自国内の諸団体が不利益を生じ

るときに権力を行使するが、通常は放っておかれる。 |

|

| 国民国家 |

nation state |

至高なる領域としての国土(=国家が空間的に占有している領域)を政治的に統 治している民(people)が国民(nation)として の 統一性やまとまりをもつ国家を、国民国家と呼ぶ[→出典リンク] ─国民とはイメージとして心に描か れた想像の政治共同体(imagined political community)である──そしてそれは、本来的に限定され、かつ主権的なもの[最高の意志決定主体]として想像されると(p.17: 邦訳1997:24)。[→ベネディクト・アンダーソン『想像の共同体』論] |

★再掲

野獣的国家

トーマス・ホッブスのリヴァイアサンに代表される国家観です。国家は強制力を国民に誇示して、恐怖や暴 力を通して支配を貫徹します。国歌や国旗は、愛国=郷土(patria)のシンボルであり、それらのシンボルを通して国家は国民に対する従属を要求し、国 民は国家に対する忠誠を誓います。(→「国家は我々自身を形づくる」)

国民は国家との契約において、国民の自由の一部を担保にしてでも、国家において国民の身体を 保護してしてもらうことに合意しており、国家による合法的な暴力——警察や軍隊——を容認できるものとする。

この国家観の変奏が「夜警国家 night watchman state」です。

夜警国家 night watcher state, Nachtwa‾cherstaat

ドイツのフェルディナント・ラッサール(Ferdinand Lassalle, 1825-1864)が、近代国家(ブルジョアの利益を守る)の役割を揶揄して表現したもので ある。つまり、夜警国家とは、外敵に対する防衛、国内治安の維持、そして最低限の福祉政策に国家機能を限定しする自由放任の国家観である。福祉国家の対概 念とされてきた。

福祉国家 welfare state

1930年代の英国がナチスドイツの戦争国家に対抗して自国の国家を表象した宣伝用語に由来 する。それが冷戦期に共産主義や全体主義国家に対する概念用語として洗練されていった。国民保険などに代表される社会福祉サービスを中心として民主主義を 維 持するという国家運営形態を理想としている。

したがって福祉国家論はルーツとしてはナショナリズムから出発し、制度を含めた諸概念の発達 は反共産主義な後期資本主義的国家(マルクス主義的な批判用語では「国家独占資本主義期の国家形態」)においてなされた。

搾取的国家

国家はおしなべて国民の利益を蹂躙し、すきあらば国民から搾取をおこなうものとみなされる。国民 にとっては、国家のこのような不道徳に対して常に警戒し、場合によっては、国家にとって反乱し、暴力をもって国家の主宰者を権力から引き下ろす権 利を有すると考える。

したがって国家は、そのような暴力が暴発しないように、国民の福祉を謳い、そのような暴発が おこらないように、ソフトに管理しようとする。

人民的国家

野獣的国家観における国家と国民が同じものであるとき、国家は国民の持ち物になり、国民は国 家と同一視されます。国家は眼にみえる実体つまり郷土(patria)などを強力なシンボルとして動員して、国民管理をおしすすめます。かつての共産主義 国家はこのようなシステムを極度に押し進めました。国民どうしを、身分制を超えて〈同志〉としてお互いに呼び慣わすやり方は、宗教共同体における〈兄弟= 姉妹〉とおなじように、情念に裏付けられたつよい精神的共同体性をメンバーに押しつけます。

多元的国家観

多元的国家における多元とは、国家を構成する諸団体の多元的共存状態のことをさす。つまり、 自由主義にもとづく利害諸団体の調整が、国家の役割である。国家は、多様な目的をもつ、それらの団体の調整に熱意を注ぐことに、民主主義の存在意味を見い だす。したがって、この社会の経済システムは新古典派経済学を軸とする自由主義経済である。経済のグローバル化に対しては、自国内の諸団体が不利益を生じ るときに権力を行使するが、通常は放っておかれる。

至

高なる領域としての国土(=国家が空間的に占有している領域)を政治的に統治している民(people)が国民(nation)としての統一性やまとまり

をもつ国家を、国民国家と呼ぶ[→出典リンク]─国民とはイメージとして心に描かれた想像の政治共同体(imagined political

community)である──そしてそれは、本来的に限定され、かつ主権的なもの[最高の意志決定主体]として想像されると(p.17:邦訳1997:

24)。[→ベネディクト・アンダーソン『想像の共同体』論]

★これからの研究課題

「21世紀の国家は、これからどうなるのか?——国家の衰退か?国家機能の強化か?」

リンク

文献

その他の情報

++

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆