ヘルスケアシステム

Health Care System

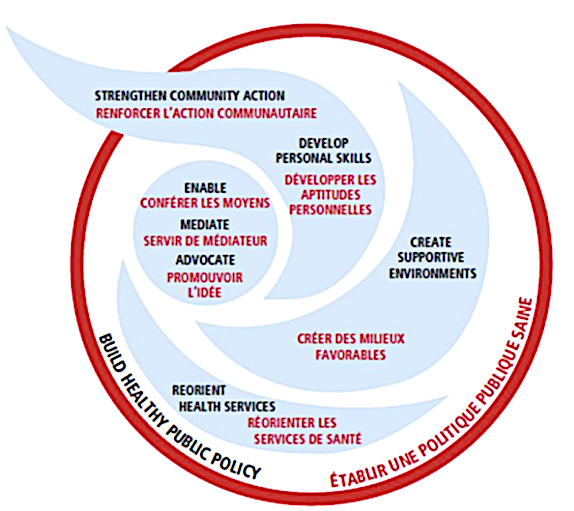

This logo was created for the First International Conference on Health Promotion held in Ottawa, Canada, in 1986.

★保健システム(Health System)、 医療システム(Health Care System)、ヘルスケアシステム(Healthcare System)とは、対象となる人々の保健上のニーズを満たすために保健医療サービスを提供する、人民、機関、資源の組織である。 世界にはさまざまな保健システムがあり、国の数だけ歴史や組織構造がある。暗黙のうちに、各国は自国のニーズと資源に応じて保健システムを設計・開発しな ければならないが、事実上すべての保健システムに共通する要素は、一次医療と公衆衛生対策である[1]。 ある国では、保健システム計画の指揮は分権化されており、市場のさまざまな利害関係者が責任を担っている。これとは対照的に、他の地域では、政府機関、労 働組合、慈善団体、宗教団体、その他の組織体の間で協力的な取り組みが存在し、それぞれの住民の特定のニーズに合わせた医療サービスのきめ細かな提供を目 指している。とはいえ、医療計画のプロセスは、革命的な変化というよりは、むしろ進化的な進行として特徴づけられることが多いことは注目に値する[2] [3]。 他の社会制度構造と同様に、保健制度は、それが発展してきた国家の歴史、文化、経済を反映する可能性が高い。こうした特殊性は、国際比較を悩ませ、複雑に し、普遍的なパフォーマティビティの基準を妨げる(→「日本のヘルスケアシステム」)。

| Outline A health system, health care system or healthcare system is an organization of people, institutions, and resources that delivers health care services to meet the health needs of target populations. There is a wide variety of health systems around the world, with as many histories and organizational structures as there are countries. Implicitly, countries must design and develop health systems in accordance with their needs and resources, although common elements in virtually all health systems are primary healthcare and public health measures.[1] In certain countries, the orchestration of health system planning is decentralized, with various stakeholders in the market assuming responsibilities. In contrast, in other regions, a collaborative endeavor exists among governmental entities, labor unions, philanthropic organizations, religious institutions, or other organized bodies, aimed at the meticulous provision of healthcare services tailored to the specific needs of their respective populations. Nevertheless, it is noteworthy that the process of healthcare planning is frequently characterized as an evolutionary progression rather than a revolutionary transformation.[2][3] As with other social institutional structures, health systems are likely to reflect the history, culture and economics of the states in which they evolve. These peculiarities bedevil and complicate international comparisons and preclude any universal standard of performance. |

概要 保健システム(Health System)、医療システム(Health Care System)、ヘルスケアシステム(Healthcare System)とは、対象となる人々の保健上のニーズを満たすために保健医療サービスを提供する、人民、機関、資源の組織である。 世界にはさまざまな保健システムがあり、国の数だけ歴史や組織構造がある。暗黙のうちに、各国は自国のニーズと資源に応じて保健システムを設計・開発しな ければならないが、事実上すべての保健システムに共通する要素は、一次医療と公衆衛生対策である[1]。 ある国では、保健システム計画の指揮は分権化されており、市場のさまざまな利害関係者が責任を担っている。これとは対照的に、他の地域では、政府機関、労 働組合、慈善団体、宗教団体、その他の組織体の間で協力的な取り組みが存在し、それぞれの住民の特定のニーズに合わせた医療サービスのきめ細かな提供を目 指している。とはいえ、医療計画のプロセスは、革命的な変化というよりは、むしろ進化的な進行として特徴づけられることが多いことは注目に値する[2] [3]。 他の社会制度構造と同様に、保健制度は、それが発展してきた国家の歴史、文化、経済を反映する可能性が高い。こうした特殊性は、国際比較を悩ませ、複雑に し、普遍的なパフォーマティビティの基準を妨げる。 |

| Goals According to the World Health Organization (WHO), the directing and coordinating authority for health within the United Nations system, healthcare systems' goals are good health for the citizens, responsiveness to the expectations of the population, and fair means of funding operations. Progress towards them depends on how systems carry out four vital functions: provision of health care services, resource generation, financing, and stewardship.[4] Other dimensions for the evaluation of health systems include quality, efficiency, acceptability, and equity.[2] They have also been described in the United States as "the five C's": Cost, Coverage, Consistency, Complexity, and Chronic Illness.[5] Also, continuity of health care is a major goal.[6] |

目標 国連システムにおける保健の指導・調整機関である世界保健機関(WHO)によると、医療制度の目標は、国民の健康、国民の期待への対応、および運営の公正 な資金調達手段である。これらの目標の達成度は、医療サービスの提供、資源の創出、資金調達、および管理という 4 つの重要な機能をシステムがどのように果たしているかにかかっている[4]。医療制度の評価には、品質、効率、受容性、公平性などの他の側面もある [2]。これらは米国では「5 つの C」として説明されている。コスト、カバレッジ、一貫性、複雑性、慢性疾患[5]。また、医療の継続性も重要な目標のひとつである[6]。 |

| Definitions Often health system has been defined with a reductionist perspective. Some authors[7] have developed arguments to expand the concept of health systems, indicating additional dimensions that should be considered: 1. Health systems should not be expressed in terms of their components only, but also of their interrelationships; 2. Health systems should include not only the institutional or supply side of the health system but also the population; 3. Health systems must be seen in terms of their goals, which include not only health improvement, but also equity, responsiveness to legitimate expectations, respect of dignity, and fair financing, among others; 4. Health systems must also be defined in terms of their functions, including the direct provision of services, whether they are medical or public health services, but also "other enabling functions, such as stewardship, financing, and resource generation, including what is probably the most complex of all challenges, the health workforce."[7] |

定義 保健システムは、しばしば還元主義的な観点から定義されてきた。一部の著者[7] は、保健システムの概念を拡大する議論を展開し、考慮すべき追加的な側面を指摘している。 1. 保健システムは、その構成要素だけで表現されるべきではなく、その相互関係も表現されるべきである。 2. 保健システムは、保健システムの制度面や供給面だけでなく、人口も包含すべきである。 3. 保健システムは、その目標の観点から捉えるべきであり、その目標には、健康の改善だけでなく、公平性、正当な期待への対応、尊厳の尊重、公正な資金調達なども含まれる。 4. 保健システムは、医療サービスや公衆衛生サービスなどの直接的なサービスの提供だけでなく、「おそらく最も複雑な課題である保健人材の確保を含む、管理、資金調達、資源の創出などのその他の支援機能」[7] といった機能も考慮して定義されなければならない。 |

| World Health Organization The World Health Organization defines health systems as follows: A health system consists of all organizations, people and actions whose primary intent is to promote, restore or maintain health. This includes efforts to influence determinants of health as well as more direct health-improving activities. A health system is, therefore, more than the pyramid of publicly owned facilities that deliver personal health services. It includes, for example, a mother caring for a sick child at home; private providers; behaviour change programmes; vector-control campaigns; health insurance organizations; occupational health and safety legislation. It includes inter-sectoral action by health staff, for example, encouraging the ministry of education to promote female education, a well-known determinant of better health.[8] |

世界保健機関 世界保健機関は、保健システムを次のように定義している。 保健システムは、健康の促進、回復、維持を主な目的とするすべての組織、人民、行動で構成される。これには、健康の決定要因に影響を与える取り組みや、よ り直接的な健康改善活動も含まれる。したがって、保健システムは、個人の保健サービスを提供する公的施設のピラミッド以上のものなんだ。例えば、自宅で病 気の子供を見守る母親、民間の医療提供者、行動変容プログラム、病媒防除キャンペーン、健康保険組織、労働安全衛生に関する法律なども含まれる。また、保 健担当者が、健康の向上に重要な要素としてよく知られている女性の教育を推進するよう教育省に働きかけるなど、部門間の連携も含まれる。[8] |

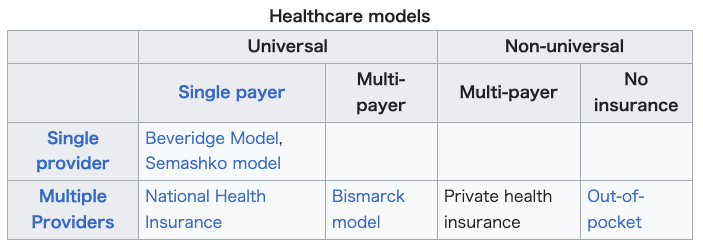

| Financial resources See also: Single-payer health care, Universal health care, and National health insurance Norfolk and Norwich University Hospital, a National Health Service hospital in the United Kingdom There are generally five primary methods of funding health systems:[9] general taxation to the state, county or municipality national health insurance voluntary or private health insurance out-of-pocket payments donations to charities  |

財源 参照:単一保険者医療制度、国民皆保険、国民健康保険 英国国立医療サービス(NHS)の病院、ノーフォーク・アンド・ノリッジ大学病院 医療制度の資金調達には、一般的に 5 つの主な方法がある[9]。 州、郡、または地方自治体への一般課税 国民健康保険 任意または民間の健康保険 自己負担 慈善団体への寄付  |

| Most

countries' systems feature a mix of all five models. One study[10]

based on data from the OECD concluded that all types of health care

finance "are compatible with" an efficient health system. The study

also found no relationship between financing and cost control.[citation

needed] Another study examining single payer and multi payer systems in

OECD countries found that single payer systems have significantly less

hospital beds per 100,000 people than in multi payer systems.[11] The term health insurance is generally used to describe a form of insurance that pays for medical expenses. It is sometimes used more broadly to include insurance covering disability or long-term nursing or custodial care needs. It may be provided through a social insurance program, or from private insurance companies. It may be obtained on a group basis (e.g., by a firm to cover its employees) or purchased by individual consumers. In each case premiums or taxes protect the insured from high or unexpected health care expenses.[citation needed] Through the calculation of the comprehensive cost of healthcare expenditures, it becomes feasible to construct a standard financial framework, which may involve mechanisms like monthly premiums or annual taxes. This ensures the availability of funds to cover the healthcare benefits delineated in the insurance agreement. Typically, the administration of these benefits is overseen by a government agency, a nonprofit health fund, or a commercial corporation.[12] Many commercial health insurers control their costs by restricting the benefits provided, by such means as deductibles, copayments, co-insurance, policy exclusions, and total coverage limits. They will also severely restrict or refuse coverage of pre-existing conditions. Many government systems also have co-payment arrangements but express exclusions are rare or limited because of political pressure. The larger insurance systems may also negotiate fees with providers.[citation needed] Many forms of social insurance systems control their costs by using the bargaining power of the community they are intended to serve to control costs in the health care delivery system. They may attempt to do so by, for example, negotiating drug prices directly with pharmaceutical companies, negotiating standard fees with the medical profession, or reducing unnecessary health care costs. Social systems sometimes feature contributions related to earnings as part of a system to deliver universal health care, which may or may not also involve the use of commercial and non-commercial insurers. Essentially the wealthier users pay proportionately more into the system to cover the needs of the poorer users who therefore contribute proportionately less. There are usually caps on the contributions of the wealthy and minimum payments that must be made by the insured (often in the form of a minimum contribution, similar to a deductible in commercial insurance models).[citation needed] In addition to these traditional health care financing methods, some lower income countries and development partners are also implementing non-traditional or innovative financing mechanisms for scaling up delivery and sustainability of health care,[13] such as micro-contributions, public-private partnerships, and market-based financial transaction taxes. For example, as of June 2011, Unitaid had collected more than one billion dollars from 29 member countries, including several from Africa, through an air ticket solidarity levy to expand access to care and treatment for HIV/AIDS, tuberculosis and malaria in 94 countries.[14] |

ほ

とんどの国では、5つのモデルがすべて混在している。OECD のデータに基づくある研究[10]

では、あらゆるタイプの医療財政は「効率的な医療制度と両立する」と結論付けている。また、この研究では、資金調達とコスト管理の間に相関関係は見られな

かった[要出典]。 OECD 諸国の単一保険者制度と複数保険者制度を比較した別の研究では、単一保険者制度では、複数保険者制度に比べ、10

万人あたりの病院病床数が大幅に少ないことが明らかになった[11]。 健康保険という用語は、一般的に、医療費を支払う保険の一形態を指す。障害や長期介護、介護の必要性をカバーする保険も含む、より広い意味で使われること もある。社会保険制度や民間保険会社を通じて提供される。団体(例えば、従業員をカバーする企業)で加入する場合もあれば、個々の消費者が購入する場合も ある。いずれの場合も、保険料や税金が、被保険者を高額または予期せぬ医療費から保護する。[要出典] 医療費の総合的なコストを計算することで、月額保険料や年額税などの仕組みを含む標準的な財務フレームワークを構築することが可能になる。これにより、保 険契約で規定された医療給付を賄うための資金が確保される。通常、これらの給付の管理は、政府機関、非営利の健康保険基金、または民間企業によって監督さ れている。[12] 多くの民間健康保険会社は、控除額、自己負担額、共同保険、保険契約除外事項、保険適用限度額などの手段を用いて、給付内容を制限することでコストを管理 している。また、既存疾患の保険適用を厳しく制限したり、拒否したりする場合もある。多くの政府制度も自己負担制度を採用しているが、政治的圧力により、 明示的な除外事項はまれであるか、または限定的である。大規模な保険制度では、医療提供者と料金について交渉する場合もある。[要出典] 多くの形態の社会保険制度は、その対象とするコミュニティの交渉力を活用して、医療提供システムのコストを管理することで、コストを管理している。例え ば、製薬会社と直接医薬品の価格交渉を行う、医療従事者と標準的な報酬について交渉する、不要な医療費を削減するなどの手段を講じる。社会制度では、国民 皆保険制度の一環として、商業保険会社や非商業保険会社の利用を伴う場合と伴わない場合のある、所得に応じた保険料拠出制度が採用されている場合もある。 本質的に、裕福な利用者はシステムへの拠出を比例的に多く支払い、貧困層のニーズを賄うため、貧困層は比例的に少ない拠出を行う。裕福な層の拠出には上限 が設定され、被保険者は最低支払額(商業保険モデルにおける免責額に類似した最低拠出金)を支払う必要がある。[出典が必要] これらの伝統的な医療財政の方法に加え、一部の低所得国や開発パートナーは、医療の提供と持続可能性の拡大のために、マイクロ貢献、官民パートナーシッ プ、市場ベースの金融取引税など、非伝統的な、あるいは革新的な財政メカニズムも導入している[13]。例えば、2011年6月時点で、ユニタイドは、ア フリカを含む29の加盟国から航空券連帯課税を通じて10億ドルを超える資金を調達し、94カ国におけるHIV/AIDS、結核、マラリアの治療とケアへ のアクセス拡大に充てている。[14] |

| Payment models In most countries, wage costs for healthcare practitioners are estimated to represent between 65% and 80% of renewable health system expenditures.[15][16] There are three ways to pay medical practitioners: fee for service, capitation, and salary. There has been growing interest in blending elements of these systems.[17] |

支払いモデル ほとんどの国では、医療従事者の人件費は、再生可能な保健システムの支出の 65% から 80% を占めると推定されている[15][16]。医療従事者に報酬を支払う方法には、サービス対価、頭割り、給与の 3 種類がある。これらのシステムの要素を融合することへの関心が高まっている[17]。 |

| Fee-for-service Fee-for-service arrangements pay general practitioners (GPs) based on the service.[17] They are even more widely used for specialists working in ambulatory care.[17] There are two ways to set fee levels:[17] By individual practitioners. Central negotiations (as in Japan, Germany, Canada and in France) or hybrid model (such as in Australia, France's sector 2, and New Zealand) where GPs can charge extra fees on top of standardized patient reimbursement rates. |

サービス対価 サービス対価制度では、一般開業医(GP)はサービスに基づいて報酬を受け取る。[17] この制度は、外来診療に従事する専門医にさらに広く採用されている。[17] 料金水準の設定には 2 つの方法がある。[17] 個々の開業医による設定。 中央交渉(日本、ドイツ、カナダ、フランスなど)またはハイブリッドモデル(オーストラリア、フランスのセクター2、ニュージーランドなど)で、GPは標準化された患者報酬率に上乗せして追加料金を請求できる。 |

| Capitation In capitation payment systems, GPs are paid for each patient on their "list", usually with adjustments for factors such as age and gender.[17] According to OECD (Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development), "these systems are used in Italy (with some fees), in all four countries of the United Kingdom (with some fees and allowances for specific services), Austria (with fees for specific services), Denmark (one third of income with remainder fee for service), Ireland (since 1989), the Netherlands (fee-for-service for privately insured patients and public employees) and Sweden (from 1994). Capitation payments have become more frequent in "managed care" environments in the United States."[17] According to OECD, "capitation systems allow funders to control the overall level of primary health expenditures, and the allocation of funding among GPs is determined by patient registrations". However, under this approach, GPs may register too many patients and under-serve them, select the better risks and refer on patients who could have been treated by the GP directly. Freedom of consumer choice over doctors, coupled with the principle of "money following the patient" may moderate some of these risks. Aside from selection, these problems are likely to be less marked than under salary-type arrangements.'[citation needed] |

キャピテーション キャピテーション支払いシステムでは、GP は「リスト」に登録されている患者 1 人につき報酬を受け取る。通常、年齢や性別などの要因に応じて調整が行われる。[17] OECD(経済協力開発機構)によると、「このシステムは、イタリア(一部手数料あり)、英国の 4 カ国(一部手数料および特定のサービスに対する手当あり)、オーストリア(特定のサービスに対する手数料あり)、 デンマーク(収入の3分の1が定額払い、残りはサービス料金)、アイルランド(1989年から)、オランダ(民間保険加入者と公務員はサービス料金制)、 スウェーデン(1994年から)で採用されている。キャピテーション支払いは、アメリカ合衆国の「マネージドケア」環境でより一般的になってきている。 [17] OECD によると、「キャピテーション制度では、資金提供者は一次医療の支出総額を管理することができ、GP 間の資金配分は患者の登録数によって決定される」。しかし、このアプローチでは、GP が患者を過度に登録し、十分な医療を提供できない、リスクの低い患者だけを選び、GP が直接治療できる患者を他の医療機関に紹介してしまう、といった問題が生じる。消費者が医師を自由に選択できることと、「患者に資金が追従する」という原 則が相まって、こうしたリスクの一部は軽減されるかもしれない。選択の問題を除けば、これらの問題は給与型制度に比べてより軽微であると考えられる。[出 典が必要] |

| Salary arrangements In several OECD countries, general practitioners (GPs) are employed on salaries for the government.[17] According to OECD, "Salary arrangements allow funders to control primary care costs directly; however, they may lead to under-provision of services (to ease workloads), excessive referrals to secondary providers and lack of attention to the preferences of patients."[17] There has been movement away from this system.[17] |

給与体系 いくつかの OECD 各国では、一般開業医(GP)は政府から給与を支給されています[17]。OECD によると、「給与体系により、資金提供者はプライマリケアの費用を直接管理することができますが、サービスの提供不足(業務負担の軽減のため)、二次医療 への過剰な紹介、患者の希望を無視した対応につながるおそれがあります」[17]。この制度からは、現在、脱却の動きがあります[17]。 |

| Value-based care In recent years, providers have been switching from fee-for-service payment models to a value-based care payment system, where they are compensated for providing value to patients. In this system, providers are given incentives to close gaps in care and provide better quality care for patients. [18] |

価値に基づく医療 近年、医療提供者は、サービス提供に対して報酬が支払われる従量制の支払いモデルから、患者に価値を提供することで報酬を得る価値に基づく医療の支払いシ ステムへと移行している。このシステムでは、医療提供者は、医療の格差を解消し、患者により質の高い医療を提供するためのインセンティブが与えられる。 [18] |

| Information resources Main articles: Health care delivery, Health information management, Health informatics, and eHealth Sound information plays an increasingly critical role in the delivery of modern health care and efficiency of health systems. Health informatics – the intersection of information science, medicine and healthcare – deals with the resources, devices, and methods required to optimize the acquisition and use of information in health and biomedicine. Necessary tools for proper health information coding and management include clinical guidelines, formal medical terminologies, and computers and other information and communication technologies. The kinds of health data processed may include patients' medical records, hospital administration and clinical functions, and human resources information.[19] The use of health information lies at the root of evidence-based policy and evidence-based management in health care. Increasingly, information and communication technologies are being utilised to improve health systems in developing countries through: the standardisation of health information; computer-aided diagnosis and treatment monitoring; informing population groups on health and treatment.[20] |

情報資源 主な記事:医療提供、健康情報管理、健康情報学、eヘルス 健全な情報は、現代の医療の提供と医療システムの効率化において、ますます重要な役割を果たしている。健康情報学は、情報科学、医学、医療の交わる分野で あり、健康および生物医学における情報の取得と利用を最適化するために必要な資源、機器、手法を扱う。適切な健康情報のコーディングおよび管理に必要な ツールとしては、臨床ガイドライン、正式な医学用語、コンピュータ、その他の情報通信技術などが挙げられる。処理される健康データには、患者の医療記録、 病院管理および臨床機能、人材情報などが含まれる。[19] 保健情報の利用は、エビデンスに基づく政策とエビデンスに基づく医療の根底にある。開発途上国では、保健情報の標準化、コンピュータ支援診断および治療モ ニタリング、人口集団への保健および治療に関する情報提供などを通じて、保健システムの改善のために情報通信技術がますます活用されている。[20] |

| Management Main articles: Health policy, Public health, Health administration, and Disease management (health) The management of any health system is typically directed through a set of policies and plans adopted by government, private sector business and other groups in areas such as personal healthcare delivery and financing, pharmaceuticals, health human resources, and public health.[citation needed] Public health is concerned with threats to the overall health of a community based on population health analysis. The population in question can be as small as a handful of people, or as large as all the inhabitants of several continents (for instance, in the case of a pandemic). Public health is typically divided into epidemiology, biostatistics and health services. Environmental, social, behavioral, and occupational health are also important subfields.[citation needed]  A child being immunized against polio Today, most governments recognize the importance of public health programs in reducing the incidence of disease, disability, the effects of ageing and health inequities, although public health generally receives significantly less government funding compared with medicine. For example, most countries have a vaccination policy, supporting public health programs in providing vaccinations to promote health. Vaccinations are voluntary in some countries and mandatory in some countries. Some governments pay all or part of the costs for vaccines in a national vaccination schedule.[citation needed] The rapid emergence of many chronic diseases, which require costly long-term care and treatment, is making many health managers and policy makers re-examine their healthcare delivery practices. An important health issue facing the world currently is HIV/AIDS.[21] Another major public health concern is diabetes.[22] In 2006, according to the World Health Organization, at least 171 million people worldwide had diabetes. Its incidence is increasing rapidly, and it is estimated that by 2030, this number will double. A controversial aspect of public health is the control of tobacco smoking, linked to cancer and other chronic illnesses.[23] Antibiotic resistance is another major concern, leading to the reemergence of diseases such as tuberculosis. The World Health Organization, for its World Health Day 2011 campaign, called for intensified global commitment to safeguard antibiotics and other antimicrobial medicines for future generations.[citation needed] |

管理 主な記事:保健政策、公衆衛生、保健行政、疾病管理(保健 あらゆる保健システムの管理は、通常、個人向け医療の提供と資金調達、医薬品、保健人材、公衆衛生などの分野において、政府、民間企業、その他の団体が採用する一連の政策や計画を通じて行われている。 公衆衛生は、人口の健康分析に基づいて、コミュニティ全体の健康に対する脅威に対処する。対象とする人口は、ごく少数の人民から、複数の大陸の全住民(例 えば、パンデミックの場合)まで、その規模はさまざまだ。公衆衛生は、通常、疫学、生物統計学、医療サービスに分けられる。環境、社会、行動、職業の健康 も重要な分野だ。[要出典]  ポリオの予防接種を受ける子供 今日、ほとんどの政府は、疾病、障害、高齢化の影響、健康格差の削減における公衆衛生プログラムの重要性を認識している。しかし、公衆衛生は、一般的に、 医療に比べて政府からの資金援助が大幅に少ない。例えば、ほとんどの国では、健康増進のための予防接種を行う公衆衛生プログラムを支援する予防接種政策が 導入されている。予防接種は、一部の国では任意であり、一部の国では義務化されている。一部の政府は、国の予防接種スケジュールにおけるワクチンの費用の 一部または全額を負担している。[要出典] 費用のかかる長期のケアや治療を必要とする多くの慢性疾患が急速に増加しているため、多くの保健管理者や政策立案者は、医療提供の実践を見直している。現 在、世界が直面している重要な健康問題の一つは、HIV/AIDSだ。[21] もう一つの大きな公衆衛生上の懸念は、糖尿病だ。[22] 2006 年、世界保健機関(WHO)によると、世界中で少なくとも 1 億 7100 万人もの人々が糖尿病を患っている。その発症率は急速に増加しており、2030 年までにその数は 2 倍になると予測されている。公衆衛生に関する論争の的となっている問題の一つは、癌やその他の慢性疾患と関連のある喫煙の抑制だ[23]。 抗生物質耐性も、結核などの病気の再流行につながる大きな問題となっている。世界保健機関は、2011 年の世界保健デーのキャンペーンで、将来世代のために抗生物質やその他の抗菌薬を保護するための世界的な取り組みの強化を求めた。[要出典] |

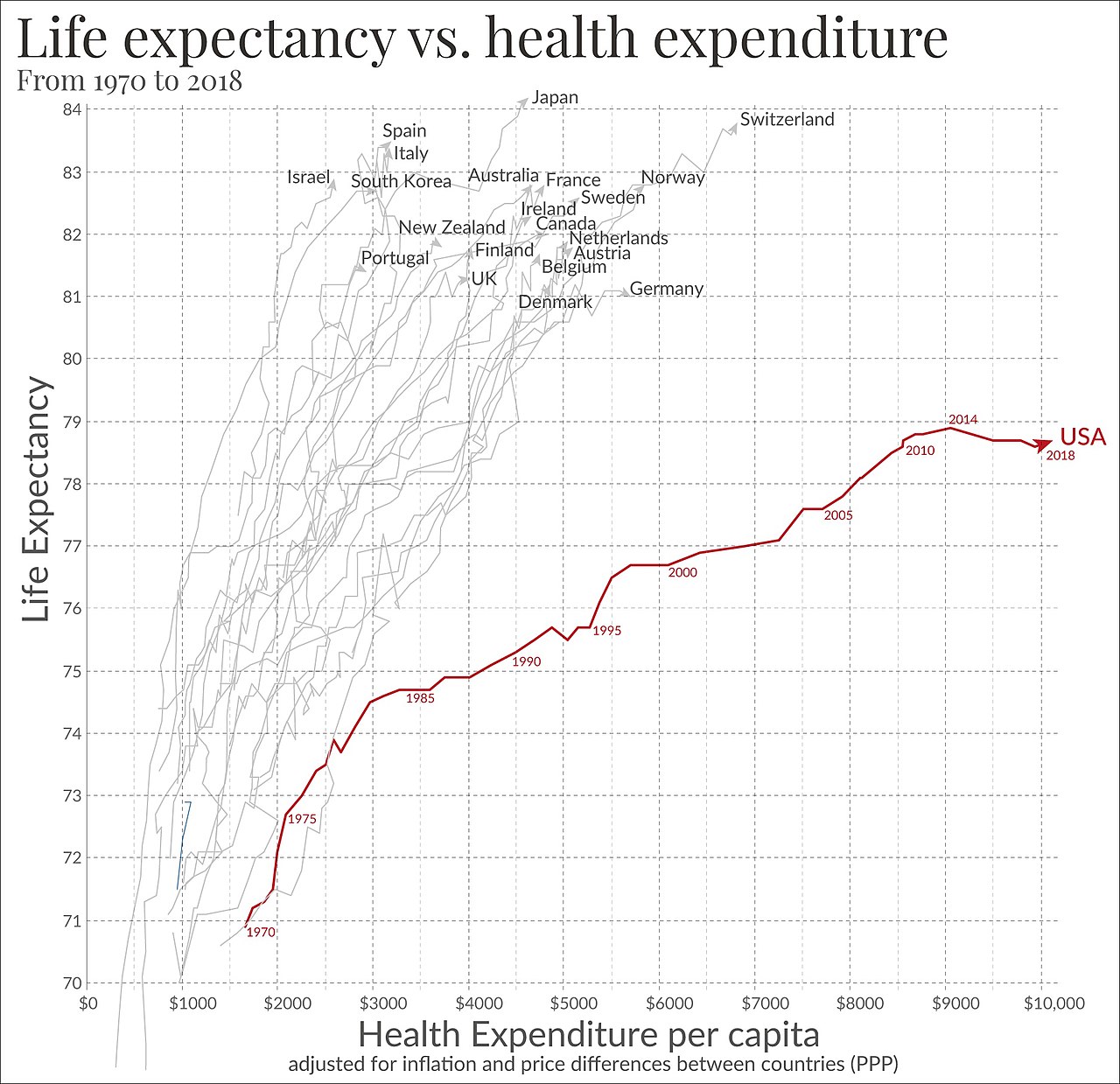

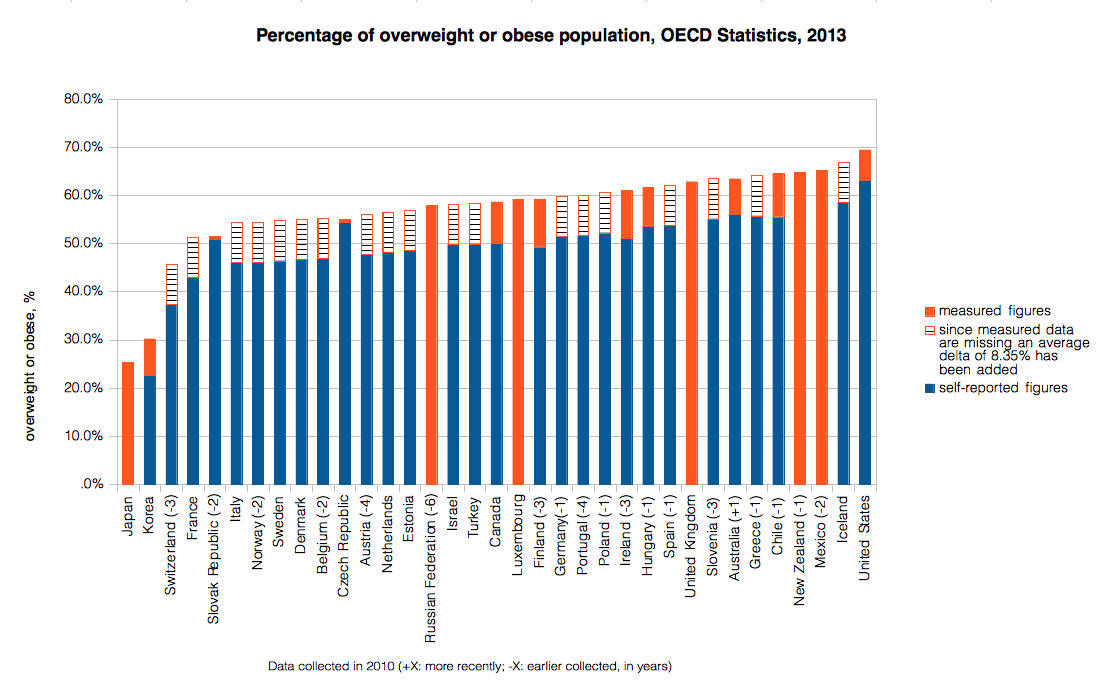

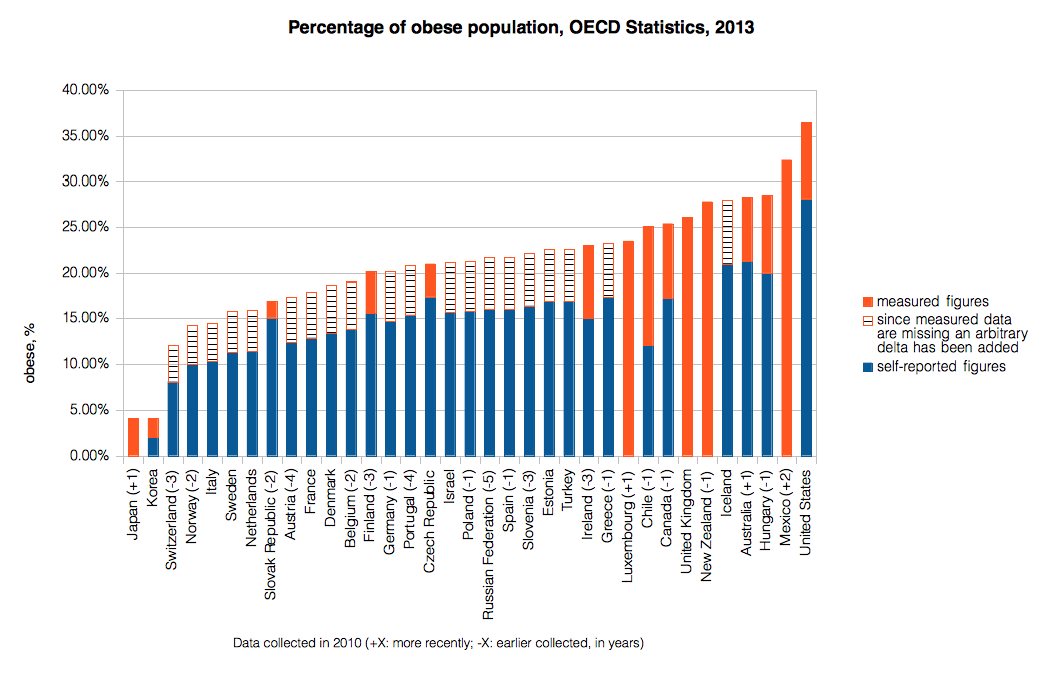

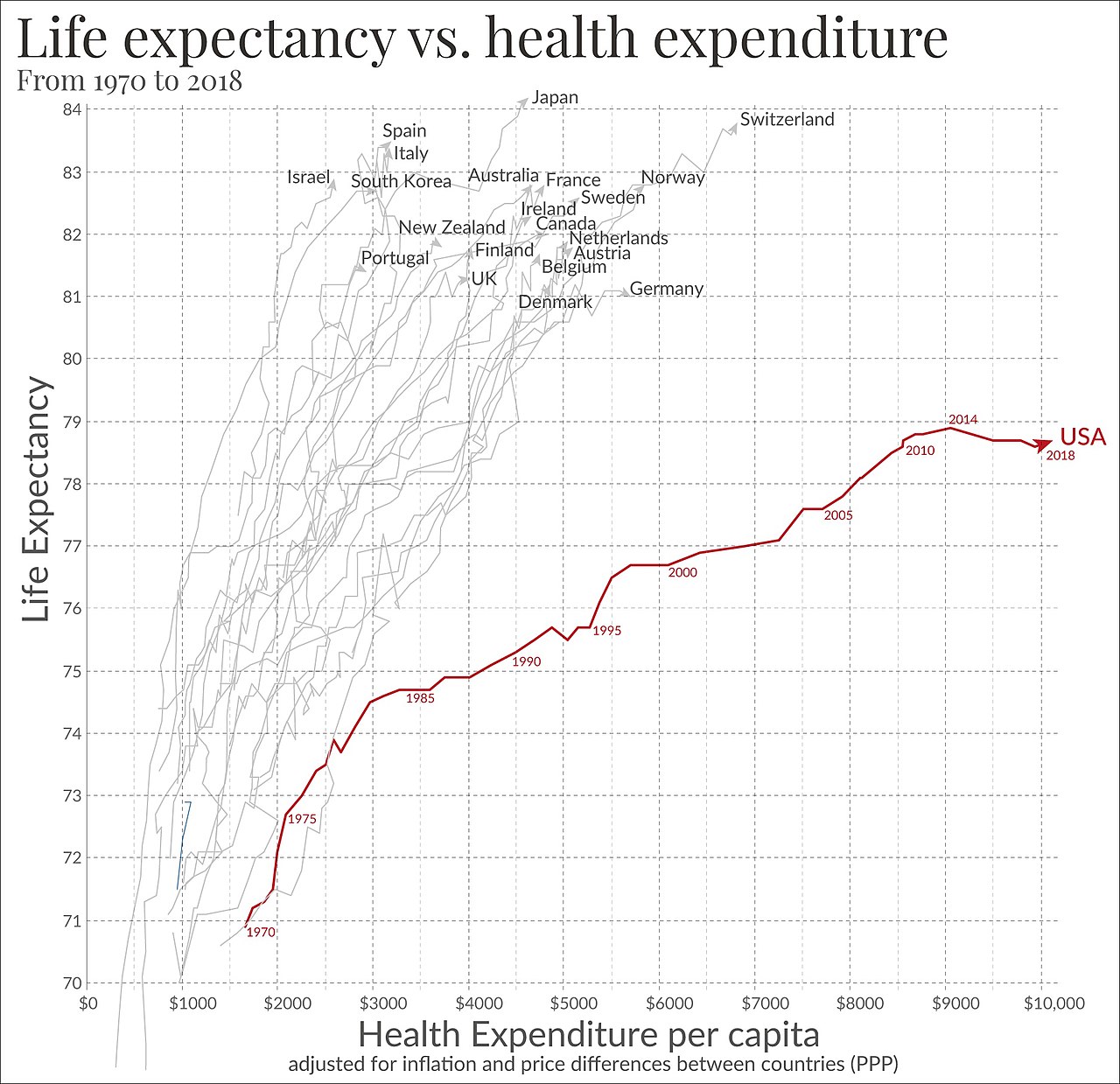

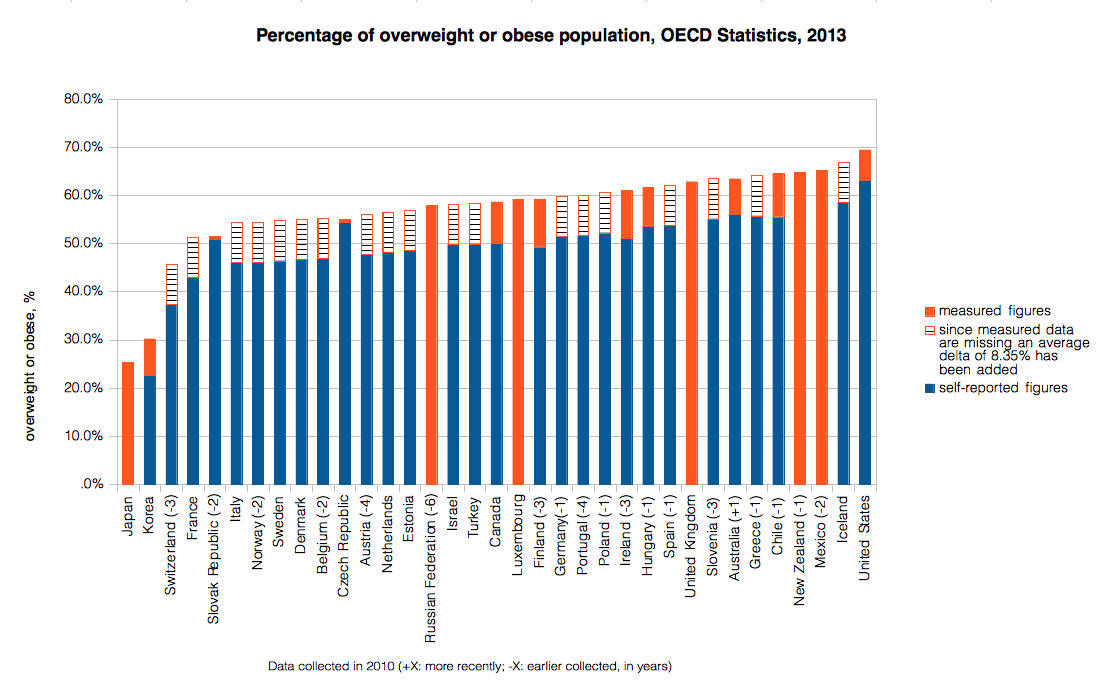

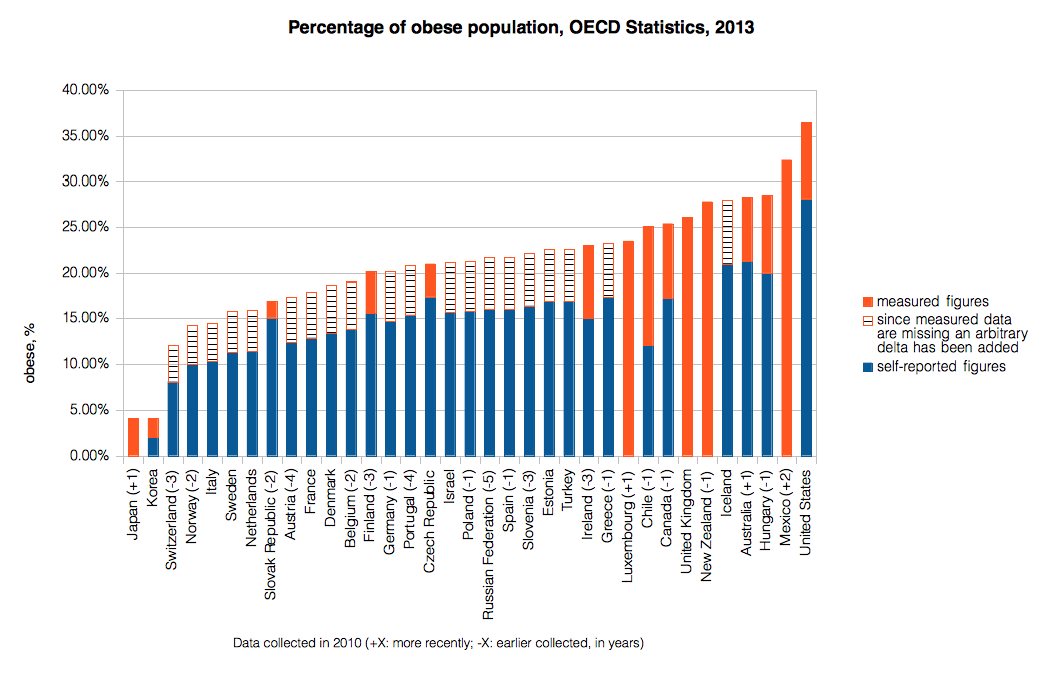

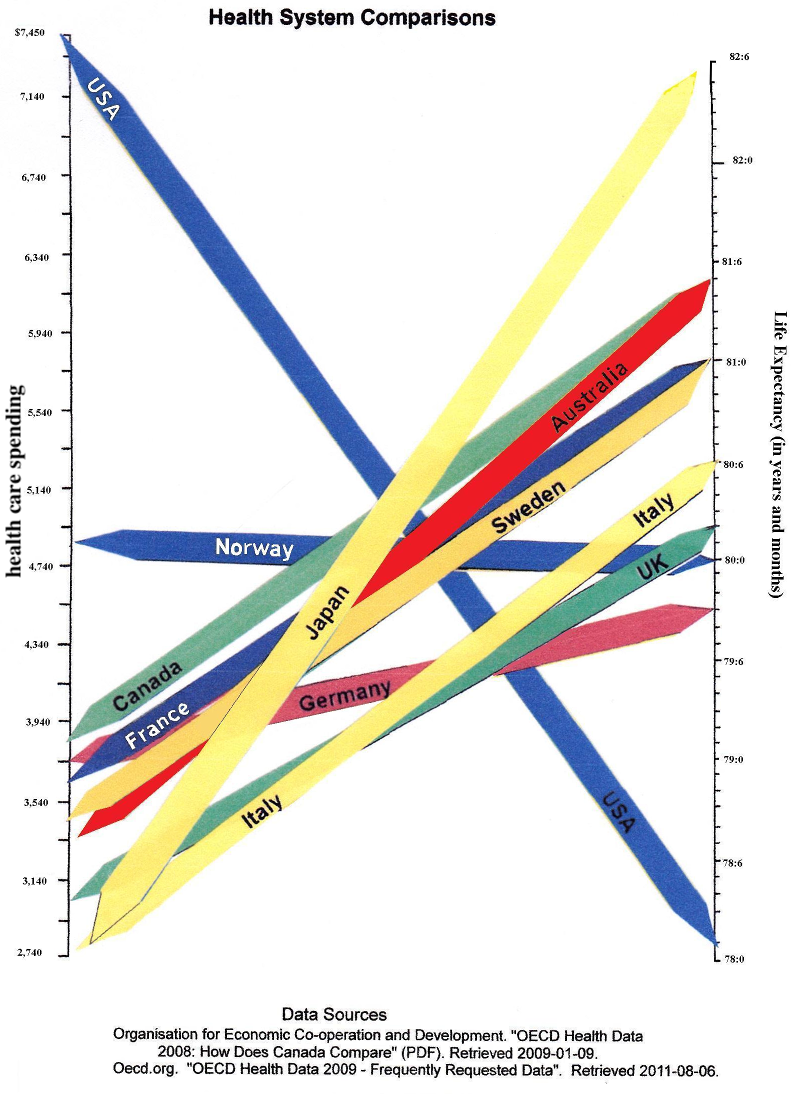

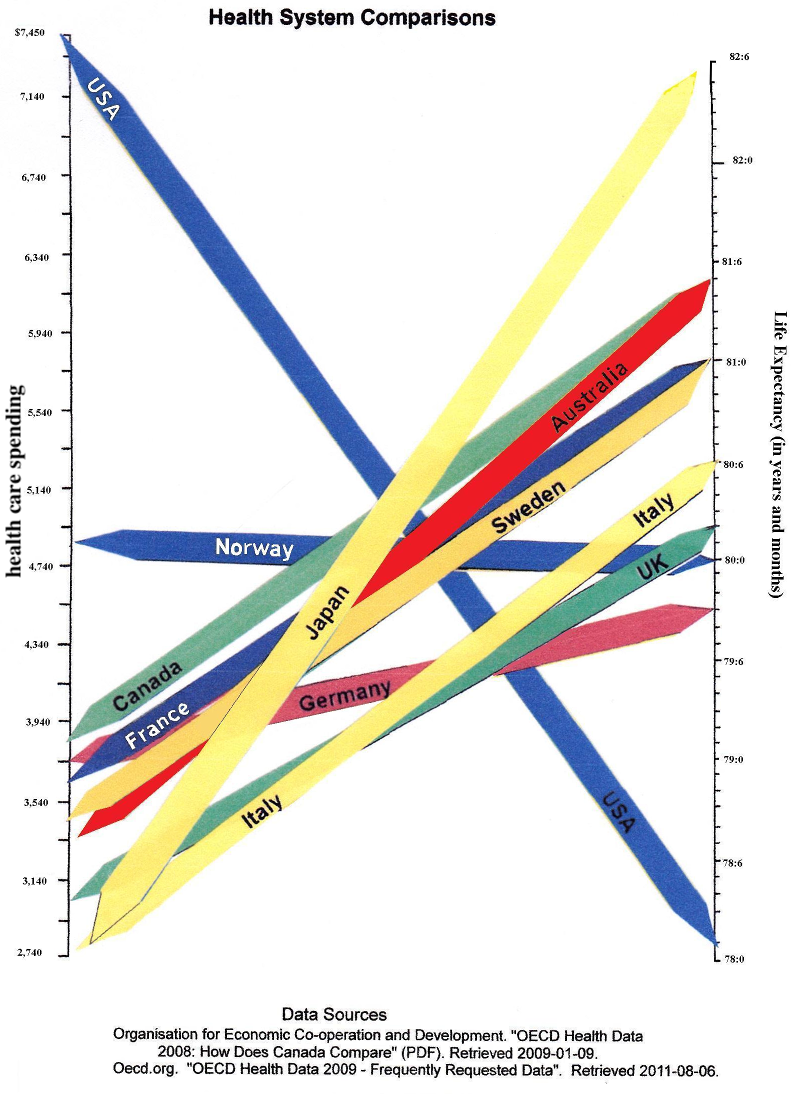

| Health systems performance See also: Health services research  Life expectancy vs healthcare spending of rich OECD countries. US average of $10,447 in 2018.[24] Since 2000, more and more initiatives have been taken at the international and national levels in order to strengthen national health systems as the core components of the global health system. Having this scope in mind, it is essential to have a clear, and unrestricted, vision of national health systems that might generate further progress in global health. The elaboration and the selection of performance indicators are indeed both highly dependent on the conceptual framework adopted for the evaluation of the health systems performance.[25] Like most social systems, health systems are complex adaptive systems where change does not necessarily follow rigid management models.[26] In complex systems path dependency, emergent properties and other non-linear patterns are seen,[27] which can lead to the development of inappropriate guidelines for developing responsive health systems.[28] Quality frameworks are essential tools for understanding and improving health systems. They help define, prioritize, and implement health system goals and functions. Among the key frameworks is the World Health Organization's building blocks model, which enhances health quality by focusing on elements like financing, workforce, information, medical products, governance, and service delivery. This model influences global health evaluation and contributes to indicator development and research.[29] The Lancet Global Health Commission's 2018 framework builds upon earlier models by emphasizing system foundations, processes, and outcomes, guided by principles of efficiency, resilience, equity, and people-centeredness. This comprehensive approach addresses challenges associated with chronic and complex conditions and is particularly influential in health services research in developing countries.[30] Importantly, recent developments also highlight the need to integrate environmental sustainability into these frameworks, suggesting its inclusion as a guiding principle to enhance the environmental responsiveness of health systems.[31] An increasing number of tools and guidelines are being published by international agencies and development partners to assist health system decision-makers to monitor and assess health systems strengthening[32] including human resources development[33] using standard definitions, indicators and measures. In response to a series of papers published in 2012 by members of the World Health Organization's Task Force on Developing Health Systems Guidance, researchers from the Future Health Systems consortium argue that there is insufficient focus on the 'policy implementation gap'. Recognizing the diversity of stakeholders and complexity of health systems is crucial to ensure that evidence-based guidelines are tested with requisite humility and without a rigid adherence to models dominated by a limited number of disciplines.[28][34] Healthcare services often implement Quality Improvement Initiatives to overcome this policy implementation gap. Although many of these initiatives deliver improved healthcare, a large proportion fail to be sustained. Numerous tools and frameworks have been created to respond to this challenge and increase improvement longevity. One tool highlighted the need for these tools to respond to user preferences and settings to optimize impact.[35] Health Policy and Systems Research (HPSR) is an emerging multidisciplinary field that challenges 'disciplinary capture' by dominant health research traditions, arguing that these traditions generate premature and inappropriately narrow definitions that impede rather than enhance health systems strengthening.[36] HPSR focuses on low- and middle-income countries and draws on the relativist social science paradigm which recognises that all phenomena are constructed through human behaviour and interpretation. In using this approach, HPSR offers insight into health systems by generating a complex understanding of context in order to enhance health policy learning.[37] HPSR calls for greater involvement of local actors, including policy makers, civil society and researchers, in decisions that are made around funding health policy research and health systems strengthening.[38]  Percentage of overweight or obese population in 2010. Data source: OECD's iLibrary, http://stats.oecd.org, retrieved 2013-12-12[39]  Percentage of obese population in 2010. Data source: OECD's iLibrary, http://stats.oecd.org, retrieved 2013-12-13[40] |

保健システムのパフォーマンス 参照:保健サービス研究  OECD 諸国の平均寿命と医療支出。2018年の米国の平均は10,447ドル[24]。 2000 年以降、世界的な保健システムの中心的な要素である各国の保健システムを強化するため、国際レベルおよび国内レベルでさまざまな取り組みがますます進めら れている。この目的を念頭に置いて、世界的な保健のさらなる進歩につながる、明確かつ制限のない各国の保健システムに関するビジョンを持つことが不可欠 だ。パフォーマンス指標の精緻化と選択は、保健システムのパフォーマンス評価に採用される概念的枠組みに大きく依存する[25]。ほとんどの社会システム と同様、保健システムは複雑な適応システムであり、変化は必ずしも厳格な管理モデルに従って起こるわけではない[26]。複雑なシステムでは、経路依存 性、創発的特性、その他の非線形パターンが見られ[27]、これらは、対応力のある保健システムの開発に不適切なガイドラインの策定につながる可能性があ る[28]。 品質フレームワークは、保健システムを理解し、改善するために不可欠なツールだ。これらは、保健システムの目標と機能を定義、優先順位付け、実施するのに 役立つ。重要なフレームワークとしては、世界保健機関(WHO)のビルディングブロックモデルがある。これは、資金、労働力、情報、医療製品、ガバナン ス、サービス提供などの要素に焦点を当て、保健の質を向上させるものだ。このモデルは、グローバルな保健評価に影響を与え、指標の開発と研究に貢献してい る[29]。 ランセット・グローバルヘルス委員会(Lancet Global Health Commission)の 2018 年のフレームワークは、効率性、回復力、公平性、人民中心主義の原則に基づき、システムの基盤、プロセス、成果を重視することで、これまでのモデルをさら に発展させたものです。この包括的なアプローチは、慢性かつ複雑な疾患に伴う課題に対処するもので、開発途上国の保健サービス研究に特に大きな影響を与え ている[30]。重要なことは、最近の動向では、これらのフレームワークに環境の持続可能性を統合する必要性も強調されており、保健システムの環境対応力 を強化するための指針原則として、その組み込みが提案されていることだ[31]。 保健システムの意思決定者が、標準的な定義、指標、測定基準を用いて、保健システムの強化[32](人材開発[33] を含む)を監視・評価するのを支援するため、国際機関や開発パートナーによって、さまざまなツールやガイドラインが発表されている。世界保健機関 (WHO)の保健システム開発ガイダンスタスクフォースのメンバーが 2012 年に発表した一連の論文を受けて、Future Health Systems コンソーシアムの研究者たちは、「政策実施のギャップ」に十分な焦点が当てられていないと主張している。エビデンスに基づくガイドラインを、必要な謙虚さ を持ち、限られた分野によって支配されたモデルに固執することなく試すためには、ステークホルダーの多様性と保健システムの複雑さを認識することが重要だ [28][34]。医療サービスは、この政策実施のギャップを克服するために、品質改善イニシアチブを実施することが多い。これらのイニシアチブの多くは 医療の改善をもたらすものの、その大部分は持続しない。この課題に対応し、改善の持続性を高めるため、数多くのツールやフレームワークが作成されてきた。 そのうちの一つは、これらのツールがユーザーの設定や好みに応じて最適化される必要性を強調している。[35] 保健政策・システム研究(HPSR)は、支配的な保健研究の伝統による「学問分野の独占」に異議を唱える、新しい学際的な分野です。この分野は、こうした 伝統が、保健システムの強化を妨げる、時期尚早で不適切に狭い定義を生み出していると主張しています[36]。HPSR は、低・中所得国に焦点を当て、すべての現象は人間の行動と解釈によって構築されるという相対主義的な社会科学のパラダイムを参考としています。このアプ ローチを用いて、HPSR は、保健政策の学習を強化するために、複雑な状況の理解を深めることで、保健システムに関する洞察を提供している[37]。HPSR は、保健政策の研究や保健システムの強化に関する資金調達に関する意思決定に、政策立案者、市民社会、研究者などの地域関係者のより一層の関与を求めてい る[38]。  2010 年の過体重または肥満の人口の割合。データ出典:OECDのiLibrary、http://stats.oecd.org、2013年12月12日取得[39]  2010年の肥満人口の割合。データ出典:OECDのiLibrary、http://stats.oecd.org、2013年12月13日取得[40] |

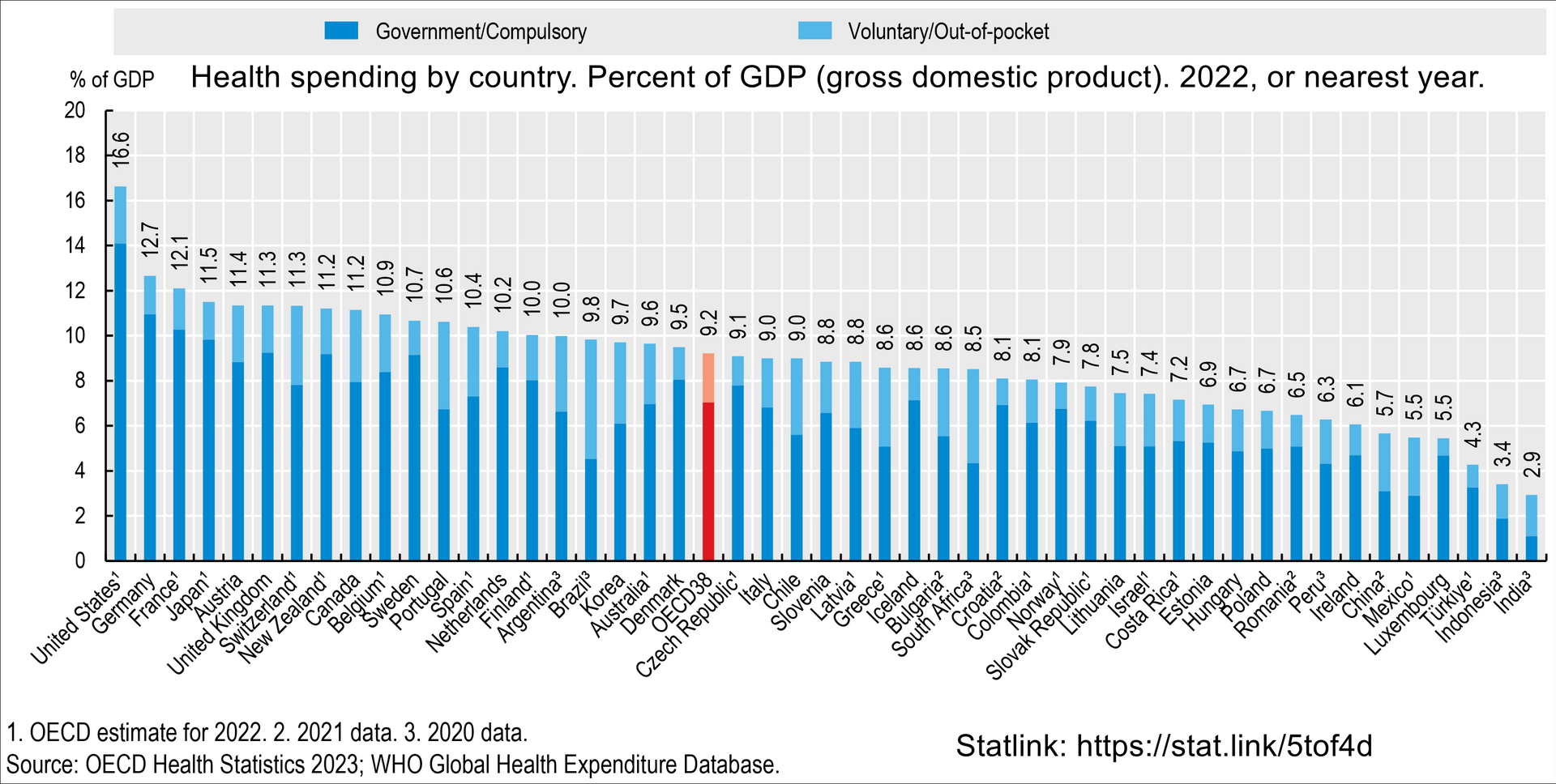

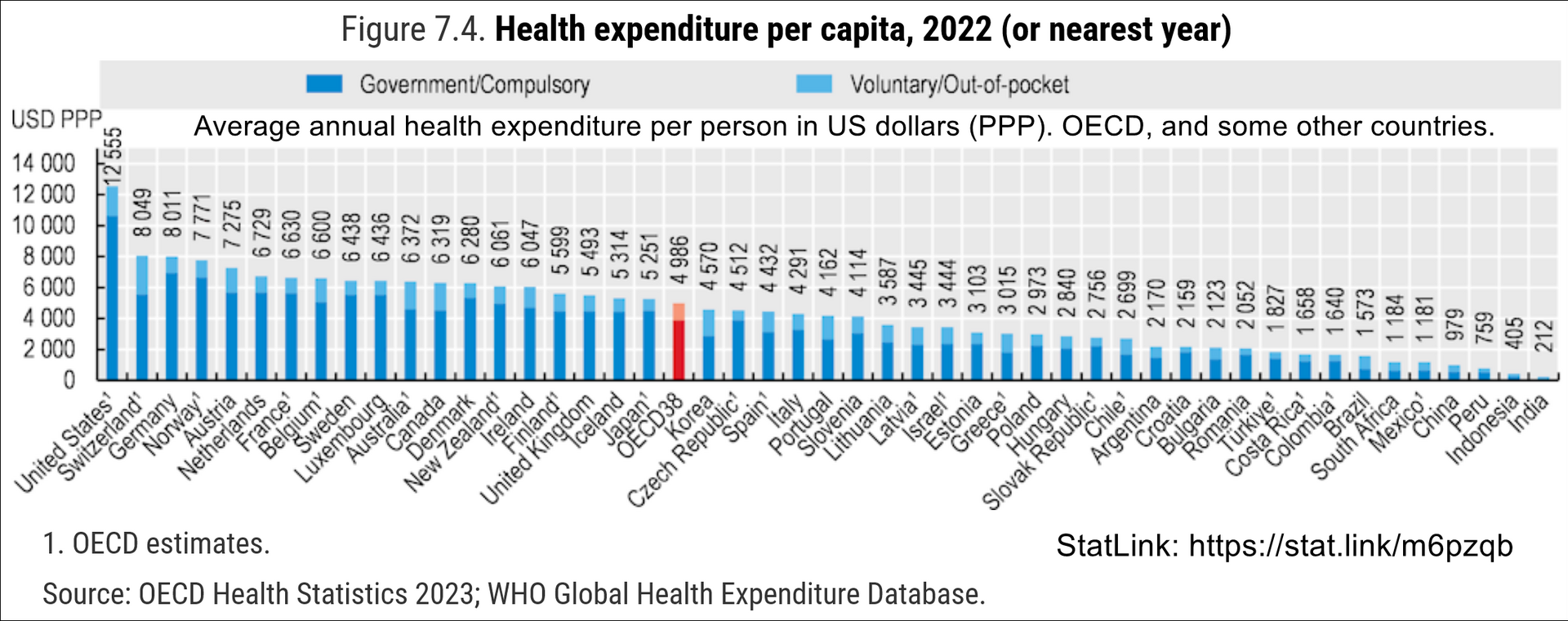

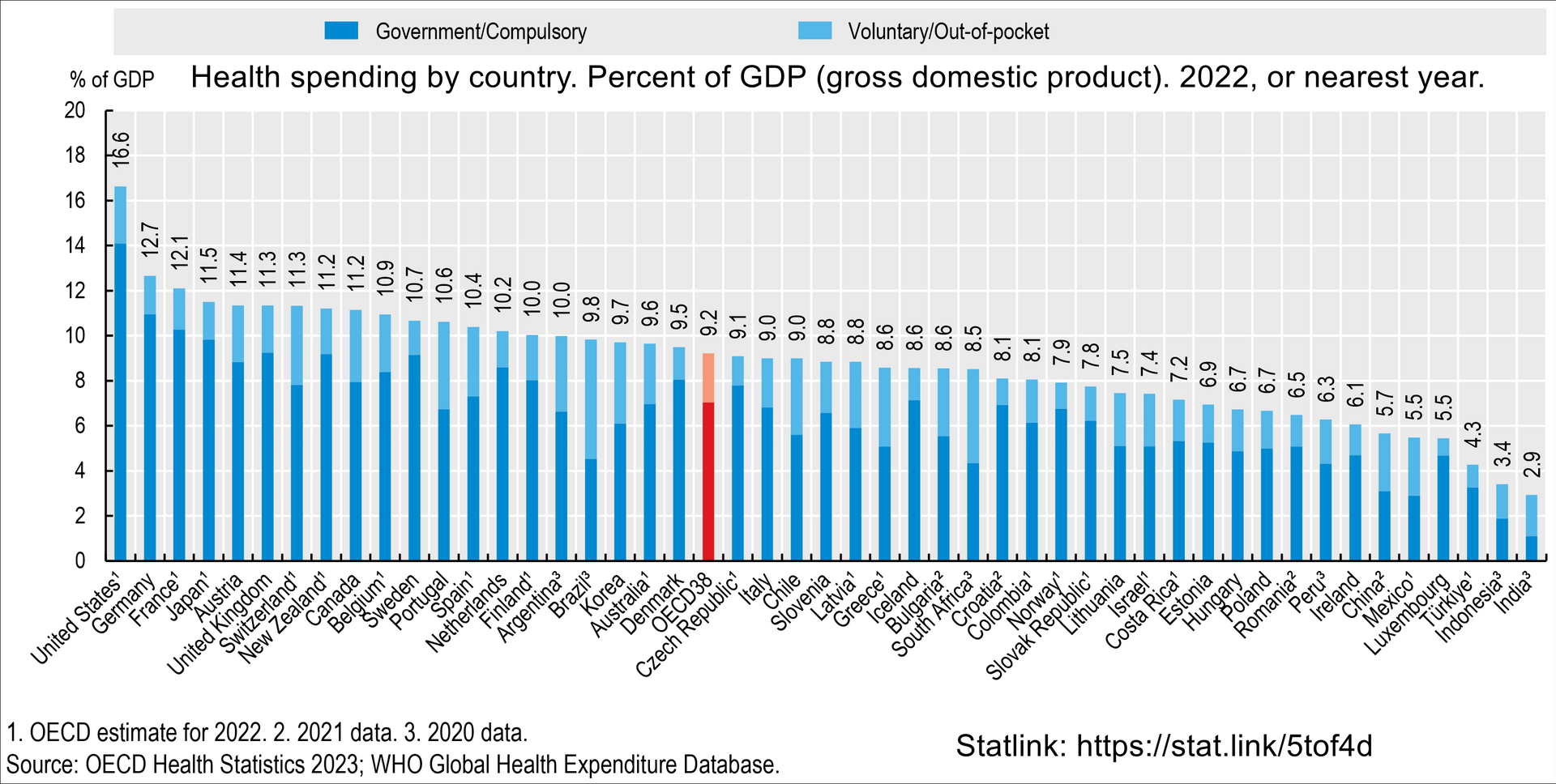

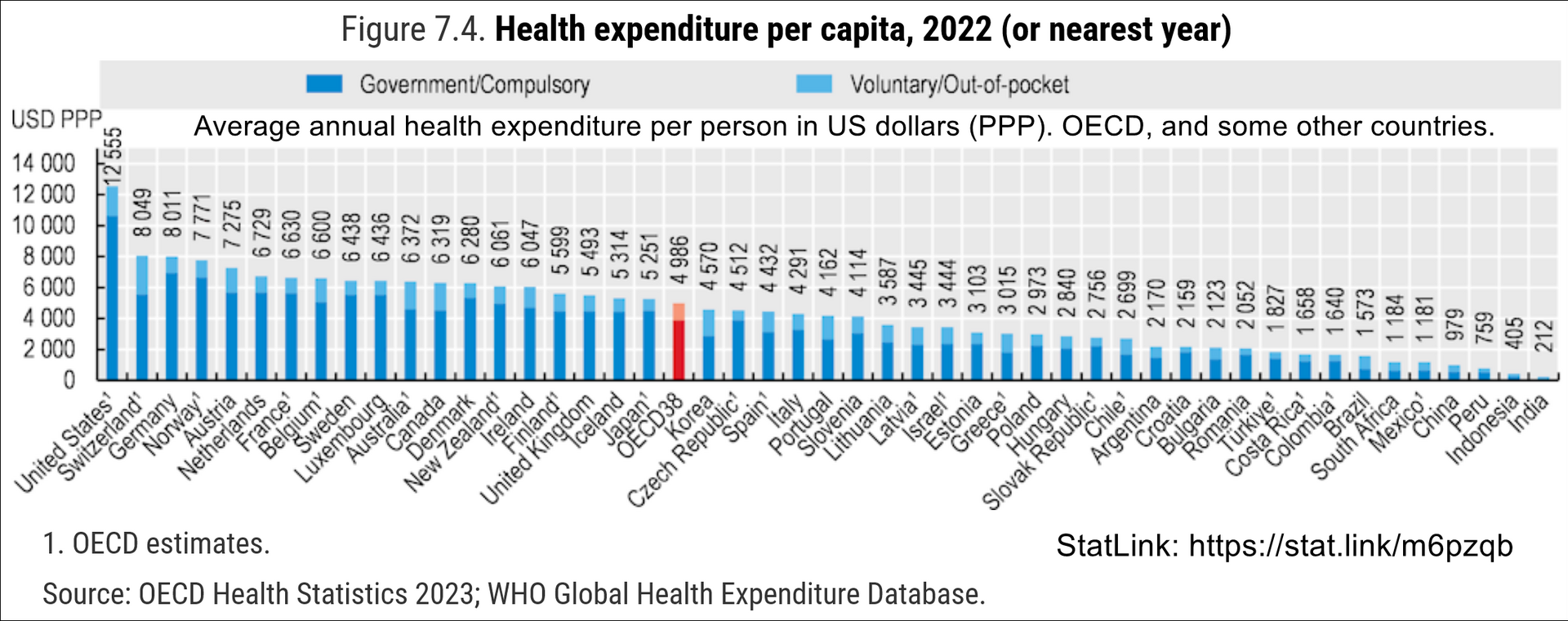

| Spending See also: Health economics, Health spending as percent of gross domestic product (GDP) by country, and List of countries by total health expenditure per capita Expand the OECD charts below to see the breakdown: "Government/compulsory": Government spending and compulsory health insurance. "Voluntary": Voluntary health insurance and private funds such as households' out-of-pocket payments, NGOs and private corporations. They are represented by columns starting at zero. They are not stacked. The 2 are combined to get the total. At the source you can run your cursor over the columns to get the year and the total for that country.[41] Click the table tab at the source to get 3 lists (one after another) of amounts by country: "Total", "Government/compulsory", and "Voluntary".[41]  Health spending by country. Percent of GDP (Gross domestic product). For example: 11.2% for Canada in 2022. 16.6% for the United States in 2022.[41]  Total healthcare cost per person. Public and private spending. US dollars PPP. For example: $6,319 for Canada in 2022. $12,555 for the US in 2022.[41] |

支出 関連項目:保健経済学、国内総生産(GDP)に占める保健支出の割合(国別)、1人あたりの保健支出総額(国別) 以下の OECD のグラフを展開して、内訳をご覧ください。 「政府/強制」:政府支出および強制健康保険。 「任意」:任意健康保険および家計の自己負担、NGO、民間企業などの民間資金。 これらはゼロから始まる列で表されている。積み重ねられていない。2つを合計して総額を得る。 出典では、列にカーソルを合わせると、その国の年と総額が表示される。[41] 出典の表タブをクリックすると、国別の金額の3つのリスト(連続して表示)が表示される:「総額」、「政府/強制」、「任意」。[41]  国別の保健支出。GDP(国内総生産)に対する割合。例:2022 年のカナダの 11.2%。2022 年の米国の 16.6%。[41]  1 人あたりの医療総費用。公的支出と民間支出。米ドル PPP。例:2022 年のカナダは 6,319 ドル。2022 年の米国は 12,555 ドル。[41] |

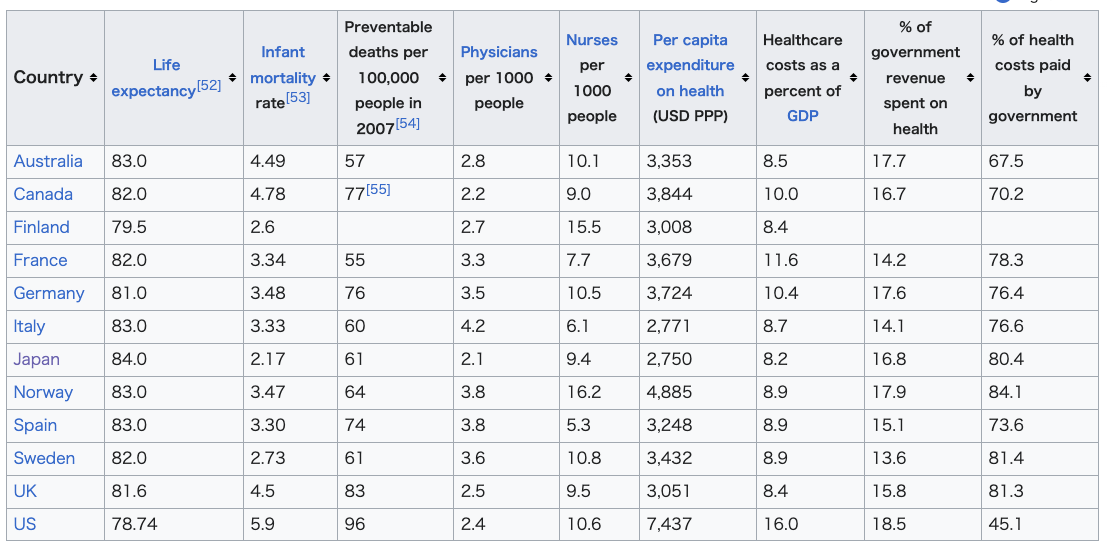

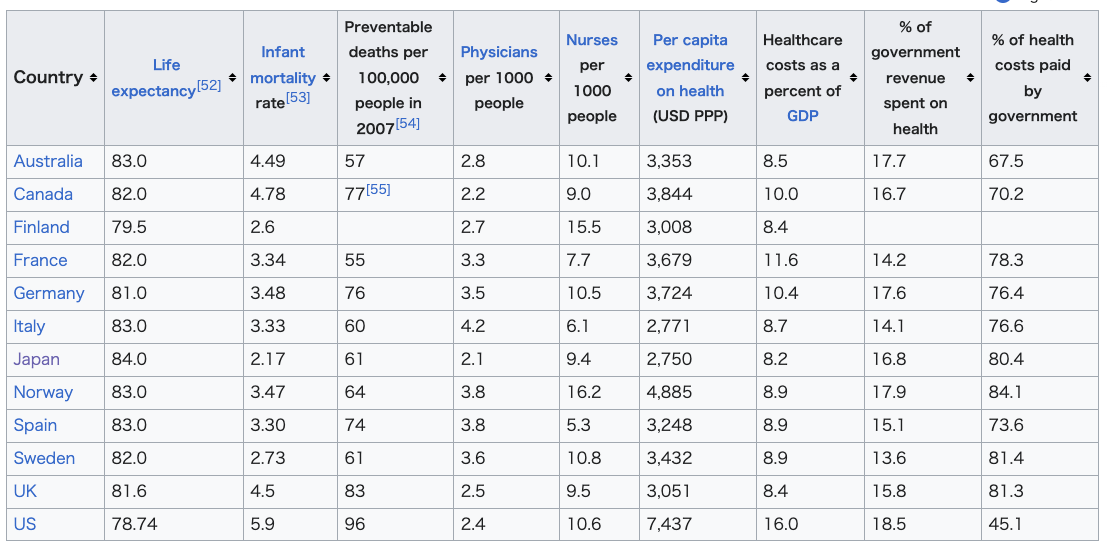

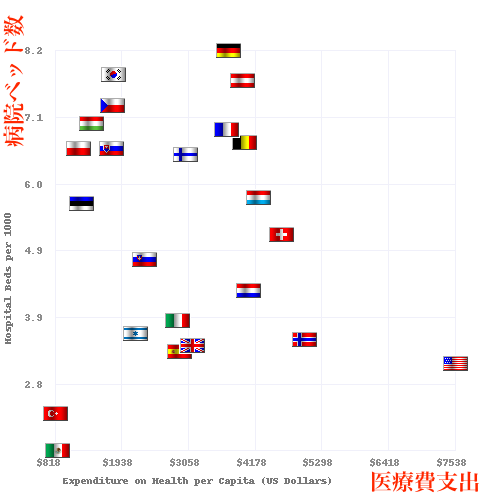

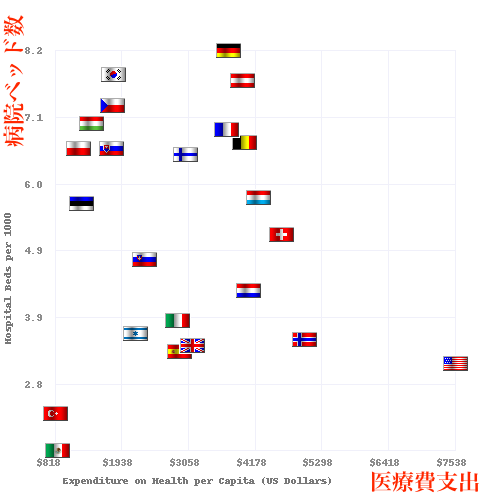

| International comparisons See also: List of countries by quality of health care, List of countries by health expenditure covered by government, Health care systems by country, Health care prices in the United States, and Healthcare in Europe  Chart comparing 2008 health care spending (left) vs. life expectancy (right) in OECD countries Health systems can vary substantially from country to country, and in the last few years, comparisons have been made on an international basis. The World Health Organization, in its World Health Report 2000, provided a ranking of health systems around the world according to criteria of the overall level and distribution of health in the populations, and the responsiveness and fair financing of health care services.[4] The goals for health systems, according to the WHO's World Health Report 2000 – Health systems: improving performance (WHO, 2000),[42] are good health, responsiveness to the expectations of the population, and fair financial contribution. There have been several debates around the results of this WHO exercise,[43] and especially based on the country ranking linked to it,[44] insofar as it appeared to depend mostly on the choice of the retained indicators. Direct comparisons of health statistics across nations are complex. The Commonwealth Fund, in its annual survey, "Mirror, Mirror on the Wall", compares the performance of the health systems in Australia, New Zealand, the United Kingdom, Germany, Canada and the United States. Its 2007 study found that, although the United States system is the most expensive, it consistently underperforms compared to the other countries.[45] A major difference between the United States and the other countries in the study is that the United States is the only country without universal health care. The OECD also collects comparative statistics, and has published brief country profiles.[46][47][48] Health Consumer Powerhouse makes comparisons between both national health care systems in the Euro health consumer index and specific areas of health care such as diabetes[49] or hepatitis.[50] Ipsos MORI produces an annual study of public perceptions of healthcare services across 30 countries.[51]  Physicians and hospital beds per 1000 inhabitants vs Health Care Spending in 2008 for OECD Countries. The data source is OECD.org - OECD.[47][48] Since 2008, the US experienced big deviations from 16% GDP. In 2010, the year the Affordable Care Act was enacted, health care spending accounted for approximately 17.2% of the U.S. GDP. By 2019, before the pandemic, it had risen to 17.7%. During the COVID-19 pandemic, this percentage jumped to 18.8% in 2020, largely due to increased health care costs and economic contraction. Post-pandemic, health care spending relative to GDP declined to 16.6% by 2022.[56][57] |

国際比較 参照:医療の質による国別一覧、政府による医療支出による国別一覧、国の医療制度、米国の医療費、ヨーロッパの医療  2008年の医療支出(左)と平均寿命(右)を比較したOECD諸国 医療制度は国によって大きく異なり、ここ数年、国際的な比較が行われている。世界保健機関(WHO)は、「世界保健報告書 2000」において、国民の健康の全体的なレベルと分布、医療サービスの対応力および公正な資金調達という基準に基づいて、世界の医療制度をランク付けし た。 [4] WHO の「世界保健報告書 2000 – 保健システム:パフォーマンスの向上(WHO、2000 年)」[42] によると、保健システムの目標は、国民の健康、国民の期待への対応力、および公正な財政負担である。このWHOの調査結果[43]、特にそれにリンクした 国別ランキング[44]については、採用された指標の選択に大きく依存しているように見えたことから、いくつかの議論が交わされてきた。 各国間の保健統計の直接比較は複雑だ。コモンウェルス基金は、年次調査「Mirror, Mirror on the Wall」で、オーストラリア、ニュージーランド、英国、ドイツ、カナダ、米国の保健システムのパフォーマンスを比較している。2007 年の調査では、米国の医療制度は最も費用がかかるものの、他の国々と比較すると一貫してパフォーマンスが低いことが明らかになった[45]。この調査で米 国と他の国々の大きな違いは、米国だけが国民皆保険制度を採用していない点だ。OECD も比較統計を収集し、各国の概要を公表している[46][47][48]。Health Consumer Powerhouse は、ユーロ健康消費者指数における各国の国民医療制度と、糖尿病[49] や肝炎[50] などの特定の医療分野について比較を行っている。 Ipsos MORI は、30 カ国における医療サービスに対する国民の認識に関する年次調査を実施している[51]。  2008年のOECD諸国の1000人あたりの医師数および病院病床数と医療支出。データ出典:OECD.org - OECD[47][48]。2008年以降、米国はGDPの16%から大きく乖離しています。アフォーダブル・ケア法が施行された2010年、米国の医療 支出はGDPの約17.2%を占めていた。パンデミック前の 2019 年には、17.7% に上昇していた。COVID-19 のパンデミックの間、この割合は 2020 年に 18.8% に急上昇したが、これは主に医療費の増加と経済の縮小によるものだ。パンデミック後、GDP に占める医療費の割合は 2022 年までに 16.6% に低下すると予測されている。[56][57] |

|

|

|

|

| Acronyms in healthcare Catholic Church and health care Clinical Health Promotion Community health Comparison of the health care systems in Canada and the United States Consumer-driven health care Cultural competence in health care Global health Genetic testing List of countries by health insurance coverage Health administration Health care Health care provider Health care reform Health crisis Health equity Health human resources Health insurance Health policy Health promotion Health services research Healthy city Hospital network Medicine National health insurance Occupational safety and health Philosophy of healthcare Primary care Primary health care Public health Publicly funded health care Single-payer health care Social determinants of health Socialized medicine Timeline of global health Two-tier health care Universal health care |

医療における頭字語 カトリック教会と医療 臨床健康増進 地域保健 カナダと米国の医療制度の比較 消費者主導の医療 医療における文化的能力 グローバルヘルス 遺伝子検査 健康保険加入率の高い国の一覧 保健行政 医療 医療提供者 医療改革 健康危機 健康の公平性 医療人材 健康保険 健康政策 健康増進 医療サービス研究 健康都市 病院ネットワーク 医学 国民健康保険 労働安全衛生 医療の哲学 プライマリケア プライマリヘルスケア 公衆衛生 公的資金による医療 単一の保険者による医療 健康の社会的決定要因 社会主義医療 世界保健の年表 二層医療 国民皆保険 |

| Universal health coverage World Health Organization: Health Systems |

国民皆保険 世界保健機関:保健システム |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Health_system |

☆ここからが本編『ヘルマン医療人類学 : 文化・健康・病い』の解説(→「講義:ヘルスケアシステム」と同じ内容)

+++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

ヘルマン医療人類学 : 文化・健康・病い / セシル・G・ヘルマン著 ; 辻内琢也監訳責任,金剛出版 , 2018./ Culture, health, and illness / Cecil G. Helman, CRC Press, Taylor & Francis Group , 2007

+++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

第4章 ケアと治療:さまざまなヘルスケアセクター

第5章 医者--患者の相互関係

第6章 ジェンダーと生殖(→「医療による統治性」)

第15章 疫学における文化的要素(→「医療による統治性」)

+++

第4章 ケアと治療:さまざまなヘルスケアセクター

1. 多元的ヘルスケア:社会文化的側面

私たちは多文化医療について何を考えないとならない か?:テキスト編

私たちは多文化医療 について何を考えないとならないか?:スライド編

2. ヘルスケアの3つのセクター (→Kleinman, Arthur, Patients and healers in the context of culture : an exploration of the borderland between anthropology, medicine, and psychiatry. 1980.)

2.1 民間セクター popular sector

community of

suffering(p.84)

2.2 民俗セクター folk sector

2.2.1 シャーマン

ブリヤートにおけるシャーマン,87

2.2.2 民俗的治療のメリットとデメリット

2.2.3 民俗治療師の訓練

2.2.4 民俗治療師の「専門職化」

TBA

2.2.5 中国とインドの伝統治療

2.2.6 補完的代替医療

CAM(→ホリスティック医療運動)

unconventional

medicine, 94.

2.3 専門職セクター professional sector

allopathy

bio-medicine, 生物医学、生物医療(→近代医学/現代医療)

2.3.1 医療システム

2.3.2 医療システムの比較

2.3.3 医療専門職

2.3.4 病院

2.3.5 医療テクノロジーの隆盛

2.3.6 西洋医療の「危機」

医原病(→医療化)

"Iatrogenesis (from the Greek for "brought forth by the healer") refers to any effect on a person, resulting from any activity of one or more other persons acting as healthcare professionals or promoting products or services as beneficial to health, which does not support a goal of the person affected"- Iatrogenesis.

3. 治療者のネットワーク

4. 英国における多元的ヘルスケア

4.1 民間セクター

4.1.1 自助グループ

4.2 民俗セクター

4.2.1 補完的代替医療の専門職組織

4.2.2 補完代替医療実践者による診察

4.3 専門職セクター

4.3.1 国民保健サービス

4.3.2 プライベート医療

4.4 英国におけるヘルスケア・システム

第5章 医 者--患者の相互関係

1. 「疾病」:医師のものの見方

1.0.1 疾病

1.0.2 還元主義

1.1 いくつもの医療モデル

1.2 道徳システムとしての医療

2. 「病い」:患者のものの見方

2.1 「健康」の定義と病むこと

2.2 説明モデル Explanatory models, by Arthour Kleinman, 1980.

2.2.1 説明モデルの文脈

2.3 民俗的病い

心臓疲労(イラン)138

衰弱する心臓(パンジャブ出身者)138

2.3.1 身体化

2.4 病いのメタファー

2.4.1 がんのメタファー

2.4.2 病いのメタファーの比較

2.5 病いの原因の一般の人の理論

2.5.1 個人

2.5.2 自然界

2.5.3 人びとの世界

2.5.4 超自然的世界

2.6 病いの原因(病因論)の分類

2.6.1 病いと不幸の物語

2.6.2 非言語的物語

3.病いについての子どものものの見方

4. 医師---患者間の診察をめぐる問題

4.1 医師の診察を受けたり受けなかったりする 理由

4.2 病いの表現

4.3 医師--患者間の問題

4.3.1 「患者」の定義の違い

4.3.2 説明モデルの不一致

4.3.3 病いなき疾病(disease without illness)

4.3.4 疾病なき病い(illness without disease)

4.3.5 用語の問題

4.3.6 治療の問題

4.3.7 文脈の役割

5. 医師----患者関係:関係向上のための方法

5.1 「病い」を理解すること

5.2 コミュニケーションを改善すること

5.3 自己を省みる力を高めること

5.4 「病い」と「疾病」の両方に対処すること

5.5 多様性を尊重すること

5.6 文脈(社会的・文化的背景)を理解するこ

と

「医療における統治性」に続く

リンク(医療人類学)

リンク(統治性)

文献

その他の情報

U' should not be number one, but only one!!!

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆