| 環世界 |

Umwelt |

|

環世界(ウンヴェルト、Umwelt)=かんせか

い、とは、ある生物——種内で共有する知覚があることが前提——が経験している知覚世界のことをさす。人間や類縁の他の動物(例:哺乳類)は、さまざまな

知覚能力を駆使して、世界のなかに主体的に生命活動をおこなっている、つまり生きている。生物が、そのことを自覚するか否かとは無関係に——あるいは問わ

ずに、生物はさまざまな知覚経験を有しており、外界の刺激に反応したり、その外界にふさわしい行動(例:被捕食者に対して攻撃をしかけそれを殺傷し、摂食

する)をおこなっている。生物の行動とセットになった、このような知覚世界を、バルト系ドイツ人のヤコブ・フォン・ユクスキュル(Jakob von

Uexküll, 1864-1944)は、環世界=ウンヴェルトと呼んだ。 |

物象化

|

|

ルカーチ『歴史と階級意識』の中で出てくる言葉。『存在と時間』のなか

でも数回出てくると言われている(木田 2003:136)

|

|

| アレテイア |

Aletheia

|

Heidegger's

idea of aletheia, or disclosure (Erschlossenheit), was an attempt to

make sense of how things in the world appear to human beings as part of

an opening in intelligibility, as "unclosedness" or "unconcealedness".

(This is Heidegger's usual reading of aletheia as Unverborgenheit,

"unconcealment".)[1] It is closely related to the notion of world

disclosure, the way in which things get their sense as part of a

holistically structured, pre-interpreted background of meaning.

Initially, Heidegger wanted aletheia to stand for a re-interpreted

definition of truth. However, he later corrected the association of

aletheia with truth.

この項目以下のURL

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Heideggerian_terminology

|

ハ

イデガーの「アレテイア」あるいは「開示性」(Erschlossenheit)という概念は、世界における事物がいかにして人間にとって「開かれたも

の」として現れるかを解明しようとする試みであった。それは「閉じられていない状態」あるいは「隠されていない状態」として、理解可能性の開け口の一部と

して現れるのである。(これはハイデガーが通常「アレテイア」を「隠されていない状態」(Unverborgenheit)として解釈する見解である。)

[1]

これは世界の開示という概念と密接に関連している。つまり、事物がある種の全体的に構造化された、解釈以前の意味の背景の一部としてその意味を得る方法で

ある。当初、ハイデガーはアレテイアを真実の再解釈された定義として位置づけようとした。しかし後に、彼はアレテイアと真実との関連性を修正した。

|

| アポファンティック |

Apophantic |

Apophantic

(German: apophantisch)

An assertion (as opposed to a question, a doubt or a more expressive

sense) is apophantic. It is a statement that covers up meaning and

instead gives something present-at-hand. For instance, "The President

is on vacation", and, "Salt is Sodium Chloride" are sentences that,

because of their apophantic character, can easily be picked up and

repeated in news and gossip by 'The They.' However, the real

ready-to-hand meaning and context may be lost. |

アポファンティック

(ドイツ語: apophantisch)

断定(疑問や疑念、あるいはより表現的な意味とは対照的に)はアポファンティックである。それは意味を覆い隠し、代わりに手近にあるものを与える声明だ。

例えば「大統領は休暇中だ」や「塩は塩化ナトリウムである」といった文は、そのアポファンティックな性質ゆえに、『彼ら』と呼ばれる者たちによってニュー

スや噂話で容易に拾い上げられ繰り返される。しかし、真に即座に利用可能な意味や文脈は失われる可能性がある。 |

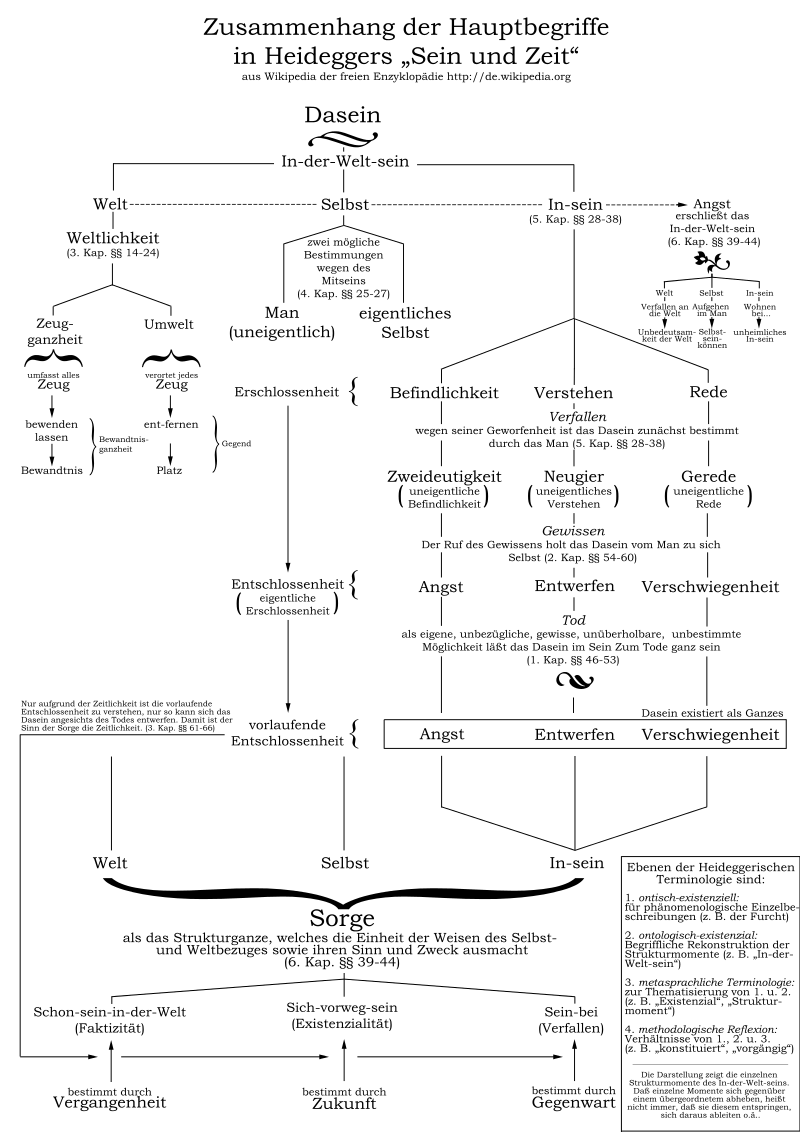

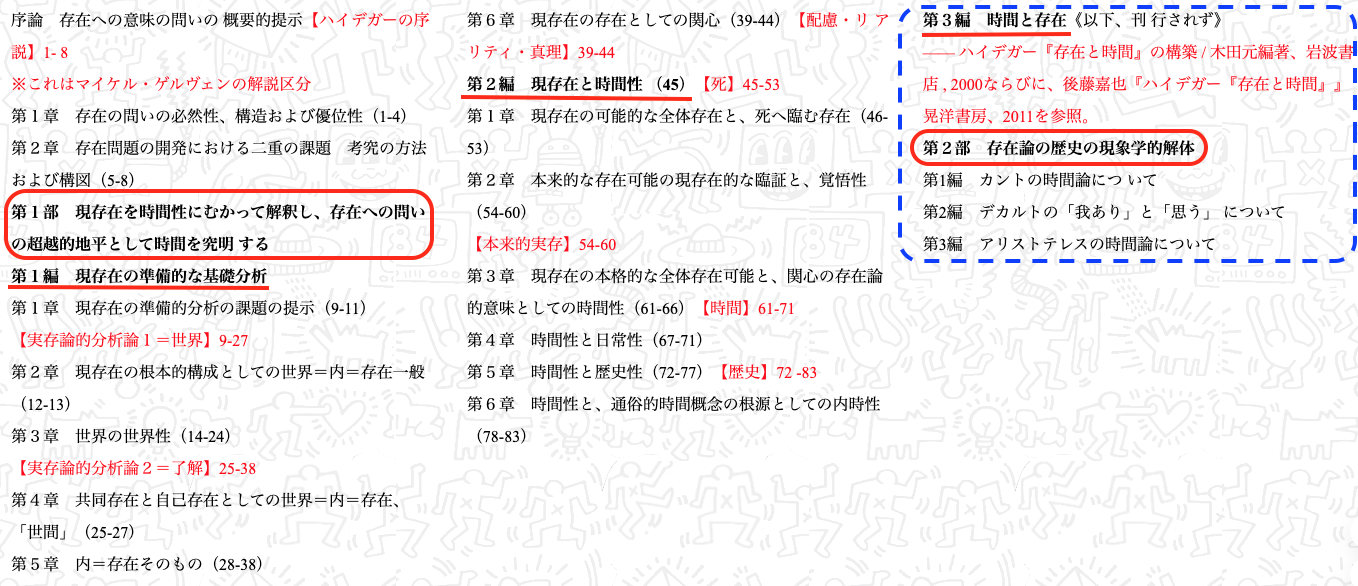

世界=内=存在

|

Being-in-the-world

|

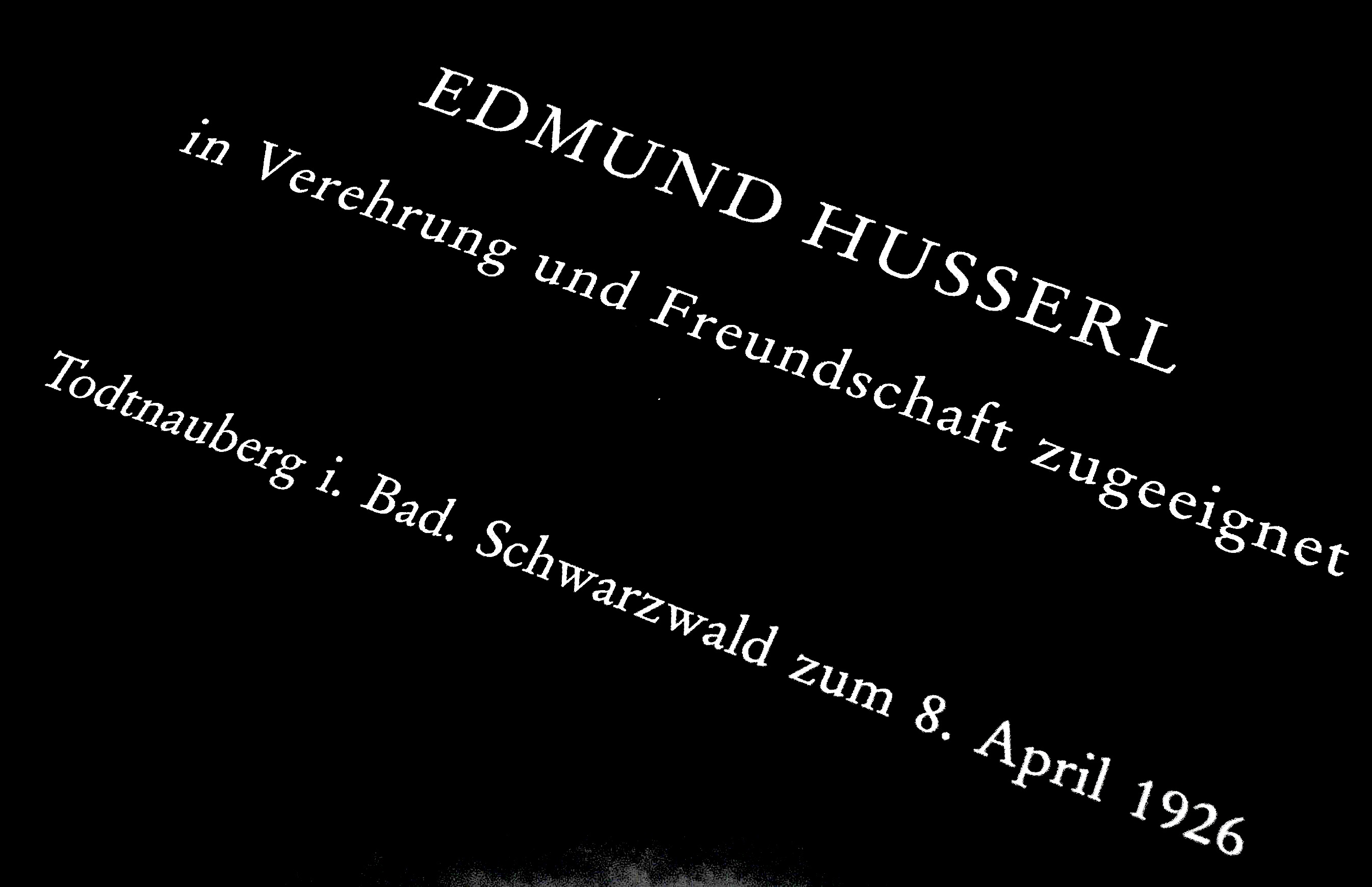

Being-in-the-world

"Being in the world" redirects here. For the documentary film, see

Being in the World.

(German: In-der-Welt-sein)

Being-in-the-world is Heidegger's replacement for terms such as

subject, object, consciousness, and world. For him, the split of things

into subject/object, as is found in the Western tradition and even in

language, must be overcome, as is indicated by the root structure of

Husserl and Brentano's concept of intentionality, i.e., that all

consciousness is consciousness of something, that there is no

consciousness, as such, cut off from an object (be it the matter of a

thought or of a perception). Nor are there objects without some

consciousness beholding or being involved with them.

At the most basic level of being-in-the-world, Heidegger notes that

there is always a mood, a mood that "assails us" in humanity's

unreflecting devotion to the world. A mood comes neither from the

"outside" nor from the "inside", but arises from being-in-the-world. A

person may turn away from a mood but that is only to another mood, as

part of facticity. Only with a mood is someone permitted to encounter

things in the world. Dasein (a co-term for being-in-the-world) has an

openness to the world that is constituted by the attunement of a mood

or state of mind. As such, Dasein is a "thrown" "projection"

(geworfener Entwurf), projecting itself onto the possibilities that lie

before it or may be hidden, and interpreting and understanding the

world in terms of possibilities. Such projecting has nothing to do with

comporting oneself toward a plan that has been thought out. It is not a

plan, since Dasein has, as Dasein, already projected itself. Dasein

always understands itself in terms of possibilities. As projecting, the

understanding of Dasein is its possibilities as possibilities. One can

take up the possibilities of "The They" self and merely follow along or

make some more authentic understanding.[2]

|

世界における存在(世界=内=存在)

「世界における存在」はここへリダイレクトされる。ドキュメンタリー映画については『世界における存在』を参照のこと。

(ドイツ語: In-der-Welt-sein)

世界における存在とは、ハイデガーが主体、客体、意識、世界といった用語に代えて用いた概念である。彼にとって、西洋の伝統や言語にさえ見られる主観/客

観への事物の分裂は克服されねばならない。これはフッサールやブレントノの意図主義概念の根幹構造が示す通り、すなわち全ての意識は何かに対する意識であ

り、対象(思考や知覚の対象である)から切り離された意識など存在しないということだ。また、何らかの意識が注視したり関与したりしない対象も存在しな

い。

世界内存在の最も基礎的なレベルにおいて、ハイデガーは常に「気配」が存在すると指摘する。それは人類が世界を無自覚に傾倒する中で「襲いかかる」気配で

ある。気配は「外」からも「内」からも来ず、世界内に在ることから生じる。人格は気配から背を向けるかもしれないが、それは事実性の一部として別の気配へ

と向かうに過ぎない。気配があって初めて、人は世界内の事物と出会うことを許されるのだ。ダーザイン(現存在)(世界内存在の同義語)は、気分の調和に

よって構成される世界への開放性を持つ。ゆえにダーザインは「投げ出された構想」(geworfener

Entwurf)であり、眼前にある可能性や隠れた可能性へと自らを投影し、可能性の観点から世界を解釈し理解する。この投影は、あらかじめ考え抜かれた

計画に沿って振る舞うこととは無関係だ。それは計画ではない。なぜならダーザイン(現存在)は、ダーザイン(現存在)として既に自らを投影しているから

だ。ダーザイン(現存在)は常に可能性の観点から自らを理解する。投影として、ダーザイン(現存在)の理解とは可能性としての可能性である。人は「彼ら」

自身の可能性を取り上げ、単にそれに従うことも、より真正な理解を試みることだってできるのだ。

|

| 死へ向かう存在 |

Being-toward-death

|

Being-toward-death

(German: Sein-zum-Tode)

Being-toward-death is not an orientation that brings Dasein closer to

its end, in terms of clinical death, but is rather a way of being.[3]

Being-toward-death refers to a process of growing through the world

where a certain foresight guides the Dasein towards gaining an

authentic perspective. It is provided by dread of death. In the

analysis of time, it is revealed as a threefold condition of Being.

Time, the present, and the notion of the "eternal", are modes of

temporality, which is the way humanity views time. For Heidegger, it is

very different from the mistaken view of time as being a linear series

of past, present and future. Instead he sees it as being an ecstasy, an

outside-of-itself, of futural projections (possibilities) and one's

place in history as a part of one's generation. Possibilities, then,

are integral to understanding of time; projects, or thrown projection

in-the-world, are what absorb and direct people. Futurity, as a

direction toward the future that always contains the past—the

has-been—is a primary mode of Dasein's temporality.

Death is that possibility which is the absolute impossibility of

Dasein. As such, it cannot be compared to any other kind of ending or

"running out" of something. For example, one's death is not an

empirical event. For Heidegger, death is Dasein's ownmost (it is what

illuminates Dasein in its individuality), it is non-relational (nobody

can take one's death away from one, or die in one's place, and we can

not understand our own death through the death of other Dasein), and it

is not to be outstripped. The "not-yet" of life is always already a

part of Dasein: "as soon as man comes to life, he is at once old enough

to die." The threefold condition of death is thus simultaneously one's

"ownmost potentiality-for-being, non-relational, and not to be

out-stripped". Death is determinate in its inevitability, but an

authentic Being-toward-death understands the indeterminate nature of

one's own inevitable death—one never knows when or how it is going to

come. However, this indeterminacy does not put death in some distant,

futural "not-yet"; authentic Being-toward-death understands one's

individual death as always already a part of one.[4]

With average, everyday (normal) discussion of death, all this is

concealed. The "they-self" talks about it in a fugitive manner, passes

it off as something that occurs at some time but is not yet

"present-at-hand" as an actuality, and hides its character as one's

ownmost possibility, presenting it as belonging to no one in

particular. It becomes devalued—redefined as a neutral and mundane

aspect of existence that merits no authentic consideration. "One dies"

is interpreted as a fact, and comes to mean "nobody dies".[5]

On the other hand, authenticity takes Dasein out of the "They", in part

by revealing its place as a part of the They. Heidegger states that

Authentic being-toward-death calls Dasein's individual self out of its

"they-self", and frees it to re-evaluate life from the standpoint of

finitude. In so doing, Dasein opens itself up for "angst", translated

alternately as "dread" or as "anxiety". Angst, as opposed to fear, does

not have any distinct object for its dread; it is rather anxious in the

face of Being-in-the-world in general—that is, it is anxious in the

face of Dasein's own self. Angst is a shocking individuation of Dasein,

when it realizes that it is not at home in the world, or when it comes

face to face with its own "uncanny" (German Unheimlich, "not

homelike"). In Dasein's individuation, it is open to hearing the "call

of conscience" (German Gewissensruf), which comes from Dasein's own

Self when it wants to be its Self. This Self is then open to truth,

understood as unconcealment (Greek aletheia). In this moment of vision,

Dasein understands what is hidden as well as hiddenness itself,

indicating Heidegger's regular uniting of opposites; in this case,

truth and untruth.[6]

|

死へ向かう存在

(ドイツ語: Sein-zum-Tode)

死へ向かう存在とは、臨床的な死という意味でダーザイン(現存在)をその終焉に近づける方向性ではなく、むしろ存在のあり方である。[3]

死へ向かう存在とは、ある予見がダーザイン(現存在)を真正な視点の獲得へと導く過程において、世界を通して成長していくことを指す。それは死への畏怖に

よって与えられる。時間の分析において、それは存在の三つの条件として明らかにされる。時間、現在、そして「永遠」という概念は、人間が時間を捉える方法

である時間性の様態である。ハイデガーにとって、それは過去・現在・未来という直線的な系列としての時間の誤った見方とは大きく異なる。むしろ彼は、時間

を超越(エクスタシー)、自己を超えたもの、未来への投影(可能性)と、自らの世代の一部としての歴史における位置づけと捉える。したがって可能性は時間

理解に不可欠であり、計画、すなわち世界への投げ込まれた投影こそが人民を吸収し導くものである。未来性とは、常に過去(過ぎ去ったもの)を含む未来への

方向性として、ダーザイン(現存在)の時間性の主要な様態である。

死は、ダーザイン(現存在)にとって絶対的な不可能性である可能性だ。ゆえに、他のいかなる終焉や「尽きる」こととも比較できない。例えば、個人の死は経

験的な出来事ではない。ハイデガーにとって死は、ダーザイン(現存在)自身の最も本質的なもの(ダーザインの個別性を照らし出すもの)であり、非関係的な

もの(誰も他人の死を奪うことはできず、代わりに死ぬこともできず、他者の死を通じて自らの死を理解することもできない)であり、追い越されることのない

ものである。生の「未到来性」は常にすでにダーザイン(現存在)の一部である:「人間が生命を得るやいなや、彼は即座に死ぬのに十分な年頃である」。死の

三つの条件は、したがって同時に「最も自己的な存在可能性であり、非関係的であり、追い越されることのないもの」なのである。死はその不可避性において確

定的だが、真正な死へ向けた存在は、自らの不可避の死の不確定性を理解する——いつ、どのように訪れるかは決して知れない。しかしこの不確定性は、死を遠

い未来の「未到来」に追いやるものではない。真正な死へ向けた存在は、個人の死が常にすでに自分の一部であることを理解するのだ。[4]

日常的な(普通の)死の議論では、こうしたことは全て隠されている。「彼ら自身」は死について逃げるように語り、いつか起こるがまだ現実として「手元にあ

る」ものではないと片付け、それが最も個人的な可能性であるという性格を隠し、誰のものでもないかのように提示する。死は軽んじられる―存在の中立的で平

凡な側面として再定義され、真正な考察に値しないとされる。「人は死ぬ」という事実は、結局「誰も死なない」という意味に解釈されるのだ。[5]

一方で、真正性はダーザイン(現存在)を「彼ら」から引き離す。その一部として「彼ら」の中に位置づけられていることを明らかにすることで。ハイデガー

は、真正な死へ向かう存在がダーザイン(現存在)の個としての自己を「彼らとしての自己」から呼び出し、有限性の立場から人生を再評価する自由を与えると

述べる。そうすることで、ダーザイン(現存在)は「アンスト」に自らを開放する。アンストは「恐怖」とも「不安」とも訳される。恐怖とは異なり、アンスト

は特定の恐怖対象を持たない。むしろ、世界内存在という一般性——すなわちダーザイン自身の自己——に直面して不安になるのだ。アンストとは、ダーザイン

(現存在)が世界において居場所を見出せないことに気づいた時、あるいは自らの「不気味さ」(ドイツ語でUnheimlich、「居心地の悪さ」)と直面

した時に生じる衝撃的な個別化である。ダーザイン(現存在)の個別化において、それは「良心の呼び声」(ドイツ語

Gewissensruf)に耳を傾ける開かれた状態となる。この呼び声は、ダーザイン(現存在)が自己でありたいと願う時に、ダーザイン(現存在)自身

の自己から発せられる。この自己は、真実(ギリシャ語

aletheia、隠されていない状態)として理解されるものに対して開かれている。この啓示の瞬間に、ダーザイン(現存在)は隠されたものそのものも、

隠蔽という状態自体も理解する。これはハイデガーが常に対立概念を統合する姿勢を示しており、この場合は真実と虚偽である。[6]

|

| 共に在ること, 共在 |

Being-with |

Being-with

(German: Mitsein)

The term "Being-with" refers to an ontological characteristic of the

human being, that it is always already[a] with others of its kind. This

assertion is to be understood not as a factual statement about an

individual, that they are at the moment in spatial proximity to one or

more other individuals, but rather a statement about the being of every

human, that in the structures of its being-in-the-world one finds an

implicit reference to other humans, as one could not live without

others. Humans have been called (by others, not by Heidegger)

"ultrasocial"[7] and "obligatorily gregarious".[8] Heidegger, from his

phenomenological perspective, calls this feature of human life

"Being-with" (Mitsein), and says it is essential to being human,[9]

classifying it as inauthentic when a person fails to recognize how

much, and in what ways, someone thinks of themself, and how they

habitually behave as influenced by our social surroundings. Heidegger

classifies it as authentic when someone pays attention to that

influence and decides independently whether to go along with it or not.

Living entirely without such influence, however, is not an option in

the Heideggerian view.

|

共に在ること

(ドイツ語: Mitsein)

「共に在ること」という用語は、人間が常に既に[a]同類の他者と共にあるという存在論的特徴を指す。この主張は、個人が現時点で空間的に他の個人と近接

しているという事実の記述としてではなく、あらゆる人間の存在に関する記述として理解されるべきである。すなわち、人間が世界内に在るという構造には、他

者なしには生きられないという事実から、他者への暗黙の参照が内在しているという主張である。人間は(ハイデガーではなく他者によって)「超社会的」

[7]であり「必然的に群居的」であると言われる。ハイデガーは現象学的観点から、この人間生活の特性を「共在(ミットザイン)」と呼び、人間存在の本質

であると述べている。そして、人がどれほど、またどのような形で他者が自分を考えているか、また社会的環境の影響を受けて習慣的にどう振る舞っているかを

認識できない場合、それを非本真的と分類する。ハイデガーは、その影響に注意を払い、それに従うか否かを独立して決断する場合を「真正な」状態と分類す

る。しかし、ハイデガーの視点では、そのような影響を完全に排除した生活は選択肢として存在しない。

|

ケア、気遣い、関心、心配

|

Care |

Care (or concern)

(German: Sorge)

A fundamental basis of being-in-the-world is, for Heidegger, not matter

or spirit but care:

Dasein's facticity is such that its Being-in-the-world has always

dispersed itself or even split itself up into definite ways of

Being-in. The multiplicity of these is indicated by the following

examples: having to do with something, producing something, attending

to something and looking after it, making use of something, giving

something up and letting it go, undertaking, accomplishing, evincing,

interrogating, considering, discussing, determining....[10]

All these ways of Being-in have concern (Sorge, care) as their kind of

Being. Just as the scientist might investigate or search, and presume

neutrality, it can be seen that beneath this there is the mood, the

concern of the scientist to discover, to reveal new ideas or theories

and to attempt to level off temporal aspects.

|

ケア(あるいは関心)

(ドイツ語:Sorge)

ハイデガーにとって、世界内存在の根本的な基盤は物質でも精神でもなく、ケアである:

ダーザイン(現存在)の実在性は、その世界内存在が常に拡散し、あるいは特定の在り方へと分裂する性質を持つ。その多様性は以下の例が示す通りである:何

かに関わる、何かを生産する、何かに注意を払い世話をする、何かを利用する、何かを放棄し手放す、引き受ける、成し遂げる、示す、尋ねる、考慮する、議論

する、決定する……。[10]

これら全ての在り方は、その存在様式として「心配(Sorge)」を伴っている。科学者が調査や探求を行い、中立性を装うように見える場合でも、その根底

には発見への情熱、新たな思想や理論を明らかにしようとする意欲、そして時間的側面を平準化しようとする試みという科学者の心情が潜んでいることがわか

る。 |

開かれた場所

|

Clearing |

Clearing

(German: Lichtung)

In German, the word Lichtung means a clearing, as in, for example, a

clearing in the woods. Since its root is the German word for light

(Licht), it is sometimes also translated as "lighting", and in

Heidegger's work it refers to the necessity of a clearing in which

anything at all can appear, the clearing in which some thing or idea

can show itself, or be unconcealed.[11] Note the relation that this has

to aletheia and disclosure.

Beings (Seiende, plural: Seienden), but not Being itself (Sein), stand

out as if in a clearing, or physically, as if in a space. Thus, Hubert

Dreyfus writes, "things show up in the light of our understanding of

being."[12] Thus the clearing makes possible the disclosure of beings

(Seienden), and also access to Dasein's own being. The clearing is not,

itself, an entity that can be known directly, in the sense in which we

know about the entities of the world. As Heidegger writes in On the

Origin of the Work of Art:

In the midst of being as a whole an open place occurs. There is a

clearing, a lighting. Thought of in reference to what is, to beings,

this clearing is in a greater degree than are beings. This open center

is therefore not surrounded by what is; rather, the lighting center

itself encircles all that is, like the Nothing which we scarcely know.

That which is can only be, as a being, if it stands within and stands

out within what is lighted in this clearing. Only this clearing grants

and guarantees to us humans a passage to those beings that we ourselves

are not, and access to the being that we ourselves are.[13]

|

開けた場所

(ドイツ語: Lichtung)

ドイツ語でLichtungという言葉は、例えば森の中の開けた場所のような意味を持つ。語源がドイツ語の「光(Licht)」であることから、「照明」

と訳されることもある。ハイデガーの著作では、あらゆるものが現れるための必要不可欠な空間、何か物や思想が自らを現す、あるいは隠蔽されない状態となる

ための空間を指す[11]。これはアレテー(aletheia)や開示(disclosure)との関係に留意すべきである。

存在者(Seiende、複数形:Seienden)は、存在(Sein)そのものではなく、あたかも開けた場所や物理的な空間の中に浮かび上がるように

現れる。ヒューバート・ドレイファスが記すように、「物事は存在の理解という光の中で現れる」のだ[12]。こうして開けた場所は存在者

(Seienden)の開示を可能にし、またダーザイン(現存在)自身の存在へのアクセスをも可能にする。この開けた場所は、それ自体が、我々が世界の実

体について知るような意味で直接知ることのできる実体ではない。ハイデガーが『芸術作品の起源について』で記すように:

存在全体の中間に開けた場所が現れる。開けた場所、照らし出された場所がある。存在するもの、存在者たちとの関係において考えられるこの開けた場所は、存

在者たちよりも高い次元にある。この開かれた中心は、したがって、存在するものによって囲まれているのではない。むしろ、照らし出す中心そのものが、私た

ちがほとんど知らない無のように、存在するものすべてを囲んでいる。存在するものは、この開けた場所において照らされているものの中に立ち、その中で際立

つことによってのみ、存在としてありうる。この開けた場所だけが、私たち人間に、私たち自身がそうではない存在たちへの通路を、そして私たち自身がそうで

ある存在へのアクセスを、与え保証するのだ。[13]

|

破壊

|

Destruktion |

Destruktion

See also: Ontotheology

Founded in the work of Martin Luther,[14] Heidegger conceptualises

philosophy as the task of destroying ontological concepts, including

ordinary everyday meanings of words like time, history, being, theory,

death, mind, body, matter, logic etc.:

When tradition thus becomes master, it does so in such a way that what

it 'transmits' is made so inaccessible, proximally and for the most

part, that it rather becomes concealed. Tradition takes what has come

down to us and delivers it over to self-evidence; it blocks our access

to those primordial 'sources' from which the categories and concepts

handed down to us have been in part quite genuinely drawn. Indeed it

makes us forget that they have had such an origin, and makes us suppose

that the necessity of going back to these sources is something which we

need not even understand. (Being and Time, p. 43)

Heidegger considers that tradition can become calcified here and there:

If the question of Being is to have its own history made transparent,

then this hardened tradition must be loosened up, and the concealments

which it has brought about dissolved. We understand this task as one in

which by taking the question of Being as our clue we are to destroy the

traditional content of ancient ontology until we arrive at those

primordial experiences in which we achieved our first ways of

determining the nature of Being—the ways which have guided us ever

since. (Being and Time, p. 44)

Heidegger then remarks on the positivity of his project of Destruktion:

...it has nothing to do with a vicious relativizing of ontological

standpoints. But this destruction is just as far from having the

negative sense of shaking off the ontological tradition. We must, on

the contrary, stake out the positive possibilities of that tradition,

and this means keeping it within its limits; and these in turn are

given factically in the way the question is formulated at the time, and

in the way the possible field for investigation is thus bounded off. On

its negative side, this destruction does not relate itself toward the

past; its criticism is aimed at 'today' and at the prevalent way of

treating the history of ontology. .. But to bury the past in nullity

(Nichtigkeit) is not the purpose of this destruction; its aim is

positive; its negative function remains unexpressed and indirect.

(Being and Time, p. 44)

|

破壊

関連項目:存在論

マーティン・ルター[14]の著作に端を発するハイデガーは、哲学を、時間、歴史、存在、理論、死、精神、身体、物質、論理などの日常的な言葉の意味を含

む、存在論的概念を破壊する作業として概念化している。

こうして伝統が支配者になるとき、それは「伝達」されるものが、その大部分が、近くではほとんどアクセスできないものとなり、むしろ隠されたものとなるよ

うな形でそうなる。伝統は、我々に受け継がれてきたものを、自明のものとして受け渡す。それは、我々に受け継がれてきたカテゴリーや概念が、その一部は真

に由来している、その根源的な「源」への我々のアクセスを遮断する。実際、それは、それらの概念がそのような起源を持っていることを我々に忘れさせ、これ

らの源に立ち返る必要性は、我々が理解する必要すらないものだと考えさせるのだ。(『存在と時間』43ページ)

ハイデガーは、伝統が随所で硬直化すると考える:

存在の問題が自らの歴史を明らかにするためには、この硬化した伝統を解きほぐし、それがもたらした隠蔽を解き放たねばならない。我々はこの課題を、存在の

問題を手がかりとして、古代存在論の伝統的内容を破壊し、存在の本質を初めて決定づけた原初的体験——それ以来我々を導いてきた方法——に到達するまでの

過程と理解する。(『存在と時間』44頁)

ハイデガーはその後、自らの破壊(デストラクション)の企ての積極性について次のように述べる:

…それは存在論的立場を悪意ある相対化することとは無関係である。しかしこの破壊は、存在論的伝統を振り払うという否定的な意味からも同様に遠い。我々は

むしろ、その伝統の肯定的可能性を明らかにしなければならない。それはすなわち、その伝統をその限界内に留めることを意味する。そしてこれらの限界は、当

時問いが立てられた方法と、それによって調査の可能な領域が画定された方法において、事実的に与えられているのである。否定的な側面において、この破壊は

過去に向かわない。その批判は『今日』と、存在論の歴史を扱う通底する方法に向けられる。…しかし過去を無(ニヒティヒカイト)に葬り去ることがこの破壊

の目的ではない。その目的は肯定的であり、その否定的な機能は表現されず間接的なままである。(『存在と時間』p.44)

|

| ダーザイン(現存在) |

Dasein |

Dasein

Main article: Dasein

This section possibly contains original research. Please improve it by

verifying the claims made and adding inline citations. Statements

consisting only of original research should be removed. (June 2021)

(Learn how and when to remove this message)

In his effort to redefine man, Heidegger introduces a statement: 'the

ownmost of Dasein consists in its existence'.[15] Heidegger

conceptualises existence around the unique qualities of man, which he

considers "its own being is an issue for it".[16] In the Heideggerian

view, man defines its own being through its actions and choices, and is

able to choose amongst possibilities, actualizing at least one of the

possibilities available while closing off others in the process. This

grasping of only some possibilities defines man as one kind of self

rather than another: a dishonest choice defines a person as dishonest,

fixing broken windows defines a person as a glazier, and so on. These

choices are made continually and on a daily basis, and so man is able

to define itself as it moves along. Therefore, living the life of a

person is a matter of constantly taking a stand on one's sense of self,

and one's sense of self being defined by taking that stand. As no

choice is 'once and for always', man has to continually keep on

choosing for his sense of self.

Added to this is that the being of everything else on the planet poses

an issue for man, as humanity deals with things as what they are and

persons as who they are. Only persons, for example, relate to others as

meaningful and fitting meaningfully into and with other things and/or

activities. Only man, being that is in the manner of existence, can

encounter another entity in its instrumental character. Again, 'to be

an issue' means to be concerned about something and to care for

something. In other words, being of Dasein as existence is so

constituted that in its very being it has a caring relationship to its

own being. This relationship is not a theoretical or self-reflective

one, but rather a pre-theoretical one which Heidegger calls a relation

or comportment of understanding. Dasein understands itself in its own

being or Dasein is in the manner that its being is always disclosed to

it. It is this disclosure of being that differentiates Dasein from all

other beings. This manner of being of Dasein to which it relates or

comports itself is called 'existence'.[17] Further, it is essential to

have a clear understanding of the term 'ownmost'. It is the English

rendering of the German wesen translated usually as 'essence' (the

'what'ness). The verbal form of German term wesen comes closer to the

Indian root vasati, which means dwelling, living, growing, maturing,

moving etc. Thus, this verbal dynamic character implied in the word

wesen is to be kept in mind to understand the nuance of the

Heideggerian usage of 'existence'. If traditionally wesen had been

translated as essence in the sense of 'whatness', for Heidegger such a

translation is unfit to understand what is uniquely human. Heidegger

takes the form of existence from the Latin word ex-sistere (to stand

out of itself) with an indication of the unique characteristic of the

being of man in terms of a dynamic 'how' as against the traditional

conception in terms of 'whatness'. Hence existence for Heidegger means

how Dasein in its very way of being is always outside itself in a

relationship of relating, caring as opposed to a relationship of

cognitive understanding to other innerworldly beings. Thereby, it is to

differentiate strictly, what is ownmost to Dasein from that of other

modes of beings that Heidegger uses the term 'existence' for the being

of man. For what is ownmost to other modes of beings, he uses the term

'present-at-hand'.

The various elements of existence are called 'existentials' and that of

what is present-at-hand are called the 'categories'. According to

Heidegger "man alone exists, all other things are (they don't exist)".

It is important to understand that this notion of 'existence' as what

is ownmost to man is not a static concept to be defined once and for

all in terms of a content, but has to be understood in terms of

something that is to be enacted that varies from individual to

individual and from time to time unlike other beings that have a fixed

essence. That being whose ownmost is in the manner of existence is

called Dasein. In German, da has a spatial connotation of either being

'there' or 'here'. Dasein thus can mean simply "being there or here".

In German, it could also refer to the existence (as opposed to the

essence) of something, especially that of man. However, Heidegger

invests this term with a new ontological meaning. The German term

Dasein consists of two components: Da and sein. In the Heideggerian

usage, the suffix -sein stands for the being of man in the manner of

existence and Da- stands for a three-fold disclosure. According to

Heidegger, the being of man is in the manner of a threefold disclosure.

That is, the ontological uniqueness of man consists in the fact that

its being becomes the da/sphere, where not only its own being, but the

being of other non-human beings as well as the phenomenon of world is

disclosed to Dasein because of which it can encounter the innerworldly

beings in their worlding character. Hence, for Heidegger the term

Dasein is a title for the ontological structure of the ontical human

being.

|

ダーザイン(現存在)

メイン記事: ダーザイン(現存在)

この節はおそらく独自研究を含んでいる。主張を検証し、インライン引用を追加することで改善してほしい。独自研究のみで構成された記述は削除すべきであ

る。(2021年6月) (このメッセージを削除する方法と時期について)

人間を再定義する試みの中で、ハイデガーは次のように述べている。「ダーザイン(現存在)の最も本質的なものは、その存在(Existenz)にある」

[15]。ハイデガーは、人間の固有の性質を中心に存在を概念化しており、彼は「存在者にとって、その存在そのものが問題である」と考えている。[16]

ハイデガーの視点では、人間は自らの行為と選択を通じて存在を定義し、複数の可能性の中から選択できる。その過程で少なくとも一つの可能性を実現しつつ、

他の可能性を閉ざすのだ。この一部の可能性のみを掴む行為が、人間をある種の自己として定義する。例えば不誠実な選択は人格を不誠実と定義し、割れた窓を

修理する行為は人格をガラス職人として定義するといった具合だ。こうした選択は絶え間なく、日常的に行われる。ゆえに人間は歩みを進める中で自らを定義し

続ける。したがって、人格として生きることは、自らの自己感覚に対して絶えず立場を表明することであり、その立場表明によって自己感覚が定義される。いか

なる選択も「一度きりで永遠に決まる」ものではないため、人間は自己感覚のために絶えず選択を続けねばならない。

これに加え、地球上のあらゆる他者の存在が人間にとって問題となる。なぜなら人類は、物事を「それ自体として」、人を「その人格として」扱うからだ。例え

ば、人だけが他者と意味ある関係を持ち、他の事物や活動と意味ある形で結びつく。存在の様式として在る人間だけが、他の存在を道具的性格において遭遇でき

るのだ。繰り返すが、「問題となる」とは何かを気にかけ、何かを気遣うことを意味する。言い換えれば、ダーザイン(現存在)の在り方は、その存在そのもの

が自らの存在に対して気遣いの関係を持つように構成されている。この関係は理論的あるいは自己反省的なものではなく、むしろハイデガーが「理解の関係」と

呼ぶ理論以前の関係である。ダーザイン(現存在)は自らの存在において自らを理解する、あるいはダーザイン(現存在)はその存在が常に自らに開示される様

態において存在する。この存在の開示こそが、ダーザイン(現存在)を他のあらゆる存在から区別する。ダーザイン(現存在)が関係し、あるいは振る舞うこの

存在様態こそが「存在」と呼ばれる。[17]さらに、「最も自明なるもの」という用語を明確に理解することが不可欠である。これは通常「本質」(「何たる

もの」の性質)と訳されるドイツ語「wesen」の英語訳である。ドイツ語「wesen」の動詞形は、インディアン語根「vasati」(住む、生きる、

育つ、成熟する、動くなど)に近い。したがって、この「wesen」という言葉に内在する動的な性格を念頭に置くことが、ハイデガーの「存在」の用法にお

けるニュアンスを理解する上で重要である。伝統的にwesenが「何たるもの」の意味で本質と訳されてきたが、ハイデガーにとってこの訳は人間に特有のも

のを理解するには不適切だ。ハイデガーは存在の形式をラテン語ex-sistere(自らから立ち出る)に求め、人間の存在の特異性を「何たるもの」とい

う伝統的概念ではなく、動的な「如何なるか」という観点から示した。したがってハイデガーにとって存在とは、ダーザイン(現存在)が在り方そのものにおい

て、常に自己の外側に位置し、関係性・関心を伴う関係性の中にあり、他の内世界的存在に対する認知的理解の関係性とは対照的であることを意味する。こうし

てハイデガーは、ダーザイン(現存在)の本質を他の存在様式と厳密に区別するために「存在」という用語を用いる。他の存在様式の本質については「手近にあ

るもの」という用語を用いるのである。

存在の様々な要素は「実存的要素」と呼ばれ、手近にあるものの要素は「カテゴリー」と呼ばれる。ハイデガーによれば「人間のみが存在する。他の全てのもの

は在る(存在しない)」。この「存在」という概念が、人間に固有のものである以上、内容によって一度限りで定義される静的な概念ではなく、固定された本質

を持つ他の存在とは異なり、個人ごとに、また時ごとに変化する、実践されるべきものとして理解されねばならない点が重要である。その最も本質的なものが存

在の仕方にある存在は、ダーザイン(現存在)と呼ばれる。ドイツ語で「da」は空間的な意味合いを持ち、「そこにある」あるいは「ここにある」を意味す

る。したがってダーザイン(現存在)は単に「そこやここにいること」を意味しうる。ドイツ語では、特に人間の存在(本質とは対照的に)を指すこともある。

しかしハイデガーはこの用語に新たな存在論的意味を与えた。ドイツ語の「ダーザイン(現存在)」は二つの要素から成る:ダ(Da)とザイン(sein)。

ハイデガーの用法では、接尾辞-seinは存在様式における人間の存在を表し、ダ-は三つの開示を表す。ハイデガーによれば、人間の存在は三つの開示とい

う様式にある。つまり、人間の存在論的独自性は、その存在が「ダ」の領域となる点にある。そこでは、自らの存在だけでなく、他の非人間的存在の存在や世界

の現象までもがダーザインに開示される。それゆえダーザインは、内世界的存在をその世界化という性格において遭遇することができるのだ。したがってハイデ

ガーにとって「ダーザイン」という語は、実存的人間の存在論的構造を指す名称なのである。

|

開示

|

Disclosure |

Disclosure

Main article: World disclosure

Further information: Reflective disclosure

(German: Erschlossenheit)

Hubert Dreyfus and Charles Spinosa write that: "According to Heidegger

our nature is to be world disclosers. That is, by means of our

equipment and coordinated practices we human beings open coherent,

distinct contexts or worlds in which we perceive, feel, act, and

think."[18]

Heidegger scholar Nikolas Kompridis writes: "World disclosure refers,

with deliberate ambiguity, to a process which actually occurs at two

different levels. At one level, it refers to the disclosure of an

already interpreted, symbolically structured world; the world, that is,

within which we always already find ourselves. At another level, it

refers as much to the disclosure of new horizons of meaning as to the

disclosure of previously hidden or unthematized dimensions of

meaning."[19] |

開示

主な記事: 世界の開示

詳細情報: 反射的開示

(ドイツ語: Erschlossenheit)

ヒューバート・ドレイファスとチャールズ・スピノサは次のように記している。「ハイデガーによれば、我々の人間の本質は世界を明らかにする存在である。つ

まり、我々人間は自らの装備と調整された実践によって、知覚し、感じ、行動し、思考する一貫した明確な文脈、すなわち世界を開くのである。」[18]

ハイデガー研究者ニコラス・コンプリディスは次のように記している:「世界開示とは、意図的な曖昧さを伴いながら、実際には二つの異なるレベルで起こる過

程を指す。一つのレベルでは、既に解釈され、象徴的に構造化された世界の開示、すなわち我々が常に既に置かれている世界そのものの開示を指す。別のレベル

では、新たな意味の地平の開示と同様に、これまで隠されていた、あるいは主題化されていなかった意味の次元の開示を指す。」 [19]

|

ディスコース

|

Discourse |

Discourse

(German: Rede)

The ontological-existential structure of Dasein consists of

"thrownness" (Geworfenheit), "projection" (Entwurf), and

"being-along-with"/"engagement" (Sein-bei). These three basic features

of existence are inseparably bound to "discourse" (Rede), understood as

the deepest unfolding of language.[20]

|

言説

(ドイツ語: Rede)

ダーザイン(現存在)の存在論的・実存的構造は、「投げ出され性」(Geworfenheit)、

「構想」(Entwurf)、そして「共在性」/「関与」(Sein-bei)から成る。これらの存在の三つの基本特徴は、「言説」(Rede)と不可分

に結びついている。言説とは、言語の最も深い展開として理解されるものである。[20]

|

道具

|

Equipment |

Equipment

This section does not cite any sources. Please help improve this

section by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may

be challenged and removed. (June 2021) (Learn how and when to remove

this message)

(German: das Zeug)

Das Zeug refers to an object in the world with which one has meaningful

dealings. A nearly un-translatable term, Heidegger's equipment can be

thought of as a collective noun, so that it is never appropriate to

call something 'an equipment'. Instead, its use often reflects it to

mean a tool, or as an "in-order-to" for Dasein. Tools, in this

collective sense, and in being ready-to-hand, always exist in a network

of other tools and organizations, e.g., the paper is on a desk in a

room at a university. It is inappropriate usually to see such equipment

on its own or as something present-at-hand.

Another, less prosaic, way of thinking of 'equipment' is as 'stuff one

can work with' around us, along with its context. "The paper one can do

things with, from the desk, in the university, in the city, on the

world, in the universe." 'Equipment' refers to the thing, and its

usefulness possibilities, and its context.

|

道具

この節は出典を一切示していない。信頼できる出典を引用してこの節を改善してほしい。出典のない記述は削除される可能性がある。(2021年6月)(この

メッセージの削除方法と時期について)

(ドイツ語: das Zeug)

「ザウグ」とは、人間が意味のある関わりを持つ世界の中の物体を指す。ほぼ翻訳不能な用語であり、ハイデガーの「用具」は集合名詞として捉えられるため、

「一つの用具」と呼ぶことは決して適切ではない。むしろ、その用法はしばしば道具を意味し、あるいはダーザイン(現存在)にとっての「~するための手段」

として機能する。道具は、この集合的な意味において、また手近にあるものとして、常に他の道具や組織のネットワークの中に存在する。例えば、紙は大学の部

屋にある机の上にある。こうした道具を単独で、あるいは手近にあるものとして見るのは通常不適切だ。

「装備」をもっと抽象的に捉えるなら、文脈と共に「周囲にある、何かを成し得るもの」と言える。「机の上で、大学で、都市で、世界で、宇宙で、何かを成し

得る紙」だ。「装備」とは物自体とその有用性の可能性、そして文脈を指す。

|

| エライニス(視界に入るもの) |

Ereignis |

Ereignis

Ereignis is translated often as "an event", but is better understood in

terms of something "coming into view". It comes from the German prefix,

er-, comparable to 're-' in English, and äugen, to look.[21][22] It is

a noun coming from a reflexive verb. Note that the German prefix er-

also can connote an end or a fatality. A recent translation of the word

by Kenneth Maly and Parvis Emad renders the word as "enowning"; that in

connection with things that arise and appear, that they are arising

'into their own'. Hubert Dreyfus defined the term as "things coming

into themselves by belonging together".

Ereignis appears in Heidegger's later works and is not easily

summarized. The most sustained treatment of the theme occurs in the

cryptic and difficult Contributions to Philosophy. In the following

quotation he associates it with the fundamental idea of concern from

Being and Time, the English etymology of con-cern is similar to that of

the German:

...we must return to what we call a concern. The word Ereignis

(concern) has been lifted from organically developing language.

Er-eignen (to concern) means, originally, to distinguish or discern

which one's eyes see, and in seeing calling to oneself, ap-propriate.

The word con-cern we shall now harness as a theme word in the service

of thought.[23]

|

Ereignis

Ereignisはしばしば「出来事」と訳されるが、「視界に入るもの」として理解する方が適切だ。これはドイツ語の接頭辞er-(英語の『re-』に相

当)と、見ることを意味するäugenに由来する。[21][22]

これは再帰動詞から派生した名詞である。なおドイツ語の接頭辞er-は終焉や宿命を暗示することもある。ケネス・マリーとパーヴィス・エマドによる近年の

訳では「enowning(自己顕現)」と表現されている。これは現れ出るものに関連し、それらが「自らのものとして」現れていることを示す。ヒューバー

ト・ドレイファスはこの用語を「共に属することによって自らに現れるもの」と定義した。

「エライニース」はハイデガーの後期著作に現れ、簡単に要約できるものではない。この主題について最も持続的に論じられているのは、難解で暗号的な『哲学

への貢献』である。以下の引用文では、彼はこの概念を『存在と時間』における「関心」という根本思想と結びつけている。英語の「con-cern」の語源

はドイツ語のそれと同様である:

...我々は「関心」と呼ぶものへと立ち返らねばならない。「出来事(Ereignis)」という言葉は有機的に発展する言語から引き出されたものであ

る。「属する(Er-eignen)」とは本来、自らの目で見るものを識別し、見ながら自らに呼び寄せ、獲得することを意味する。我々は今、この「関心

(con-cern)」という言葉を思考の道具として主題語として活用するつもりだ。[23]

|

実存(→ダーザイン)

|

Existence |

Existence

Main article: § Dasein

(German: Existenz)

|

存在

メイン記事: § ダーザイン(現存在)

(ドイツ語: Existenz)

|

実存的

|

Existentiell |

Existentiell

Main article: Existentiell

(German: Existenziell)

|

実存的

主な記事:実存的

(ドイツ語:Existenziell)

|

基礎存在論

|

Fundamental ontology |

Fundamental ontology

Main article: Fundamental ontology

Traditional ontology asks "Why is there anything?", whereas Heidegger's

fundamental ontology asks "What does it mean for something to be?".

Taylor Carman writes (2003) that Heidegger's "fundamental ontology" is

fundamental relative to traditional ontology in that it concerns "what

any understanding of entities necessarily presupposes, namely, our

understanding of that in virtue of which entities are entities."[24]

|

根本存在論(基礎存在論)

詳細な記事: 根本存在論

伝統的な存在論が「なぜ何かが存在するのか?」と問うのに対し、ハイデガーの根本存在論は「何かが存在するということは何を意味するのか?」と問う。テイ

ラー・カーマン(2003)は、ハイデガーの「根本存在論」が伝統的存在論に対して根本的であるのは、それが「あらゆる実体理解が必然的に前提とするも

の、すなわち実体が実体である所以についての我々の理解」に関わる点にあると記している。[24]

|

| ゲラッセンハイト |

Gelassenheit |

Gelassenheit

For the understanding of Gelassenheit in the Anabaptist tradition, see

Ordnung § Gelassenheit.

Often translated as "releasement",[25] Heidegger's concept of

Gelassenheit has been explained as "the spirit of disponibilité

[availability] before What-Is which permits us simply to let things be

in whatever may be their uncertainty and their mystery."[26] Heidegger

elaborated the idea of Gelassenheit in 1959, with a homonymous volume

which includes two texts: a 1955 talk entitled simply Gelassenheit,[27]

and a 'conversation' (Gespräch) entitled Zur Erörterung der

Gelassenheit: Aus einem Feldweggespräch über das Denken[28] ("Towards

an Explication of Gelassenheit: From a Conversation on a Country Path

about Thinking",[29] or "Toward an Emplacing Discussion [Erörterung] of

Releasement [Gelassenheit]: From a Country Path Conversation about

Thinking").[30] An English translation of this text was published in

1966 as "Conversation on a Country Path about Thinking".[30][31]

Heidegger borrowed the term from the Christian mystical tradition,

proximately from Meister Eckhart.[29][32][33]

|

ゲラッセンハイト

再洗礼派の伝統におけるゲラッセンハイトの理解については、秩序 § ゲラッセンハイトを参照のこと。

しばしば「解放」と訳される[25]ハイデガーのゲラッセンハイト概念は、「存在するものに対するディスポニビリテ(可用性)の精神であり、それが我々

に、物事が不確かさや神秘性の中にありながらも、単にありのままにさせることを可能にする」と説明されてきた。ハイデガーは1959年、同名の著作集でゲ

ラッセンハイトの思想を展開した。この著作集には二つのテキストが含まれる:1955年の講演「ゲラッセンハイト」[27]と、『対話

(Gespräch)』「ゲラッセンハイトの論考に向けて:思考についての田舎道での対話から」[28](原題:Zur Erörterung der

Gelassenheit: Aus einem Feldweggespräch über das

Denken)である。田舎道での思考に関する対話から」[29]、あるいは「解放(ゲラッセンハイト)の議論(エルテルトゥング)へ向けて:思考に関す

る田舎道での対話から」)。このテキストの英訳は1966年に『思考についての田舎道での対話』として出版された。ハイデガーはこの用語をキリスト教神秘

主義の伝統、特にマイスター・エックハルトから借用した。

|

| ゲステル(足場、枠組み) |

Gestell |

Gestell

Main article: The Question Concerning Technology

Heidegger once again returns to discuss the essence of modern

technology to name it Gestell. The original German meaning something

more like scaffolding, he defines it primarily as a sort of

(en)framing[34]:

Enframing means the gathering together of that setting-upon that sets

upon man, i.e., challenges him forth, to reveal the real, in the mode

of ordering, as standing-reserve. Enframing means that way of revealing

that holds sway in the essence of modern technology and that it is

itself not technological.[35]

Once he has discussed enframing, Heidegger highlights the threat of

technology. As he states, this threat "does not come in the first

instance from the potentially lethal machines and apparatus of

technology."[35] Rather, the threat is the essence because "the rule of

enframing threatens man with the possibility that it could be denied to

him to enter into a more original revealing and hence to experience the

call of a more primal truth."[35] This is because challenging-forth

conceals the process of bringing-forth, which means that truth itself

is concealed and no longer unrevealed.[35] Unless humanity makes an

effort to re-orient itself, it will not be able to find revealing and

truth.

It is at this point that Heidegger has encountered a paradox: humanity

must be able to navigate the dangerous orientation of enframing because

it is in this dangerous orientation that we find the potential to be

rescued.[36] To further elaborate on this, Heidegger returns to his

discussion of essence. Ultimately, he concludes that "the essence of

technology is in a lofty sense ambiguous" and that "such ambiguity

points to the mystery of all revealing, i.e., of truth."[35]

|

ゲステル

詳細な記事: 技術に関する問い

ハイデガーは再び現代技術の本質を論じ、それをゲステルと名付ける。ドイツ語の原義は足場のようなものだが、彼は主に一種の枠組みとして定義する

[34]:

枠組みとは、人間を包み込み、すなわち現実を秩序立てた形で「備蓄」として明らかにするよう挑む、その包み込みの集積を意味する。枠組みとは、現代技術の

本質において支配的な、その明らかにする方法を意味し、それ自体が技術的ではないのである[35]。

枠組みについて論じた後、ハイデガーは技術の本質的脅威を強調する。彼が述べるように、この脅威は「第一に、技術がもたらす潜在的に致命的な機械や装置か

ら来るものではない」[35]。むしろ脅威は本質そのものにある。なぜなら「枠組みの支配は、人間がより原初的な顕現へと入り込み、より根源的な真実の呼

びかけを体験する可能性を否定される危険を人間に突きつける」からである。[35]

なぜなら、呼び出しは現出のプロセスを隠蔽するからであり、それは真実そのものが隠され、もはや現出されていないことを意味する。[35]

人類が自らの方向性を再調整する努力をしない限り、現出と真実を見出すことはできない。

ここでハイデガーは逆説に直面する。人間は枠組みの危険な方向性の中を航行できなければならない。なぜなら、この危険な方向性の中にこそ、救われる可能性

が潜んでいるからだ。[36]

この点をさらに掘り下げるため、ハイデガーは本質に関する議論に戻る。結局のところ、彼は「技術の本質は高尚な意味で曖昧である」と結論づけ、「そのよう

な曖昧さは、あらゆる啓示、すなわち真実の神秘を指し示す」と述べている。[35]

|

| 投企性 |

Geworfenheit |

Geworfenheit

Main article: Thrownness

Geworfenheit describes man's individual existences as "being thrown"

(geworfen) into the world. For William J. Richardson, Heidegger used

this single term, "thrown-ness", to "describe [the] two elements of the

original situation, There-being's non-mastery of its own origin and its

referential dependence on other beings".[37]

|

投企性

メイン記事: 投げ出され性

投げ出され性とは、人間の個々の存在が世界に「投げ出される」(geworfen)状態を指す。ウィリアム・J・リチャードソンによれば、ハイデガーはこ

の単一の用語「投げ出され性」を用いて、「原初的状況の二つの要素、すなわち存在の自らの起源に対する非支配性と、他の存在への参照的依存性を記述した」

のである。[37]

|

ケーレ(転回)

|

Kehre |

Kehre

Kehre, or "the turn" (die Kehre) is a term rarely used by Heidegger but

employed by commentators who refer to a change in his writings as early

as 1930 that became clearly established by the 1940s. Recurring themes

that characterize much of the Kehre include poetry and technology.[38]

Commentators (e.g. William J. Richardson)[39] describe, variously, a

shift of focus, or a major change in outlook.[40]

The 1935 Introduction to Metaphysics "clearly shows the shift" to

language from a previous emphasis on Dasein in Being and Time eight

years earlier, according to Brian Bard's 1993 essay titled "Heidegger's

Reading of Heraclitus".[41] In a 1950 lecture, Heidegger formulated the

famous saying "language speaks", later published in the 1959 essays

collection Unterwegs zur Sprache, and collected in the 1971 English

book Poetry, Language, Thought.[42][43][44]

This supposed shift—applied here to cover about thirty years of

Heidegger's 40-year writing career—has been described by commentators

from widely varied viewpoints; including as a shift in priority from

Being and Time to Time and Being—namely, from dwelling (being) in the

world to doing (time) in the world.[38][45][46] This aspect, in

particular the 1951 essay "Building, Dwelling Thinking", influenced

several notable architectural theorists, including Christian

Norberg-Schulz, Dalibor Vesely, Joseph Rykwert, and Daniel Libeskind.

Other interpreters believe "the Kehre" does not exist or is overstated

in its significance. Thomas Sheehan (2001) believes this supposed

change is "far less dramatic than usually suggested", and entailed a

change in focus and method.[47] Sheehan contends that throughout his

career, Heidegger never focused on "being", but rather tried to define

"[that which] brings about being as a givenness of entities".[47][48]

Mark Wrathall[49] argued (2011) that the Kehre is not found in

Heidegger's writings but is simply a misconception. As evidence for

this view, Wrathall sees a consistency of purpose in Heidegger's

life-long pursuit and refinement of his notion of "unconcealment".

Among the notable works dating after 1930 are On the Essence of Truth

(1930), Contributions to Philosophy (From Enowning), composed in the

years 1936–38 but not published until 1989, Building Dwelling Thinking

(1951), The Origin of the Work of Art (1950), What Is Called Thinking?

(1954) and The Question Concerning Technology (1954). Also during this

period, Heidegger wrote extensively on Nietzsche and the poet Hölderlin. |

ケーレ

ケアー、すなわち「転回」(die

Kehre)は、ハイデガー自身がほとんど用いない用語だが、1930年代初期の著作における変化を指し、1940年代までに明確に確立されたと論評する

者たちが用いる。ケールレを特徴づける反復的な主題には、詩と技術が含まれる[38]。評論家(例:ウィリアム・J・リチャードソン[39])は、焦点を

移すこと、あるいは見解の大きな変化と、様々な形でこれを説明する。[40]

ブライアン・バードの1993年の論文「ハイデガーのヘラクレイトス解釈」によれば、1935年の『形而上学序説』は、8年前の『存在と時間』における

ダーザイン(現存在)への重点から言語への「転換を明らかに示している」。[41]

1950年の講義でハイデガーは「言語は語る」という有名な言葉を提唱した。これは後に1959年の論文集『言語へ向かって』に収録され、1971年の英

語版『詩・言語・思考』にも収められた。[42][43] [44]

この想定される転換——ここではハイデガーの40年に及ぶ執筆活動のうち約30年間をカバーするものとして適用される——は、多様な視点を持つ論者たちに

よって説明されてきた。その中には、『存在と時間』から『時間と存在』への優先順位の転換、すなわち世界における住まうこと(存在)から世界における行う

こと(時間)への転換として捉える見解も含まれる。[38][45] [46]

この側面、特に1951年の論文「建築、住居、思考」は、クリスチャン・ノルベルク=シュルツ、ダリボル・ヴェセリー、ヨゼフ・リクヴェルト、ダニエル・

リベスキンドといった著名な建築理論家に影響を与えた。

他の解釈者たちは、「転回」は存在しないか、その重要性が過大評価されていると考える。トーマス・シーハン(2001)は、この想定される転換は「通常示

唆されるほど劇的ではない」と主張し、焦点と方法の変化を伴うものだとする。[47]

シーハンは、ハイデガーがキャリアを通じて「存在」に焦点を当てたことはなく、むしろ「実体の与えられとして存在をもたらすもの」を定義しようとしたと論

じる。[47][48]

マーク・ラザール[49]は(2011年)、ケアーはハイデガーの著作に見出せず、単なる誤解だと論じた。この見解の根拠として、ラザールはハイデガーが

生涯にわたり「顕現」の概念を追求・洗練させた一貫した目的意識を指摘する。

1930年以降の主要著作には、『真実の本質について』(1930年)、1936年から38年に執筆されながら1989年まで未発表だった『哲学への貢献

(『顕現』より)』、『造る・住む・考える』(1951年)、『芸術作品の起源』(1950年)、『思考とは何か?』(1954年)、『技術に関する問

い』(1954年)がある。またこの時期、ハイデガーはニーチェと詩人ヘルダーリンについて多くの著作を残した。(1954年)、『技術に関する問い』

(1954年)がある。またこの時期、ハイデガーはニーチェと詩人ヘルダーリンについて多くの著作を残した。

|

| メタオントロジー |

Metontology |

Metontology

Not to be confused with Meta-ontology.

(German: Metontologie)

Metontology is a neologism Heidegger introduced in his 1928 lecture

course "Metaphysical Foundations of Logic" ("Metaphysische

Anfangsgründe der Logik im Ausgang von Leibniz"). The term refers to

the ontic sphere of human experience.[50][51] While ontology deals with

the entire world in broad and abstract terms, metontology concerns

concrete topics; Heidegger offers the examples of sexual differences

and ethics.

|

メタオントロジー

メタ存在論と混同してはならない。

(ドイツ語: Metontologie)

メタオントロジーは、ハイデガーが1928年の講義「論理学の形而上学的基礎」(「Metaphysische Anfangsgründe der

Logik im Ausgang von

Leibniz」)で導入した新語である。この用語は、人間の経験における存在論的領域を指す。[50][51]

存在論が広範かつ抽象的な観点から世界全体を扱うのに対し、メタ存在論は具体的な主題に関わる。ハイデガーは性差や倫理を例として挙げている。

|

| オンティック(存在的) |

Ontic |

Ontic

Main article: Ontic

(German: ontisch)

Heidegger uses the term ontic, often in contrast to the term

ontological, when he gives descriptive characteristics of a particular

thing and the "plain facts" of its existence. What is ontic is what

makes something what it is.

For an individual discussing the nature of "being", one's ontic could

refer to the physical, factual elements that produce and/or underlie

one's own reality –the physical brain and its substructures. Moralists

raise the question of a moral ontic when discussing whether there

exists an external, objective, independent source or wellspring for

morality that transcends culture and time.

|

オント的・オンティック・存在的

主な記事: オント的

(ドイツ語: ontisch)

ハイデガーは、特定のものの記述的特徴とその存在の「平然たる事実」を説明する際に、しばしば「オント論的」という用語と対比して「オント的」という用語

を用いる。オント的とは、何かをそれたらしめるものである。

「存在」の本質を論じる個人にとって、その存在論的側面とは、自身の現実を生み出し/支える物理的・事実的要素——すなわち物理的な脳とその下位構造——

を指し得る。道徳論者は、文化や時代を超越した、外部的で客観的かつ独立した道徳の源泉が存在するかどうかを論じる際、道徳的存在論的側面の問題を提起す

る。

|

存在論的

|

Ontological |

Ontological

(German: ontologisch)

As opposed to "ontic" (ontisch), ontological is used when the nature,

or meaningful structure of existence is at issue. Ontology, a

discipline of philosophy, focuses on the formal study of Being. Thus,

something that is ontological is concerned with understanding and

investigating Being, the ground of Being, or the concept of Being

itself.

For an individual discussing the nature of "being", the ontological

could refer to one's own first-person, subjective, phenomenological

experience of being.

|

存在論的

(ドイツ語: ontologisch)

「実在論的」(ontisch)とは対照的に、存在論的という語は、存在の本質や意味ある構造が問題となる場合に使われる。哲学の一分野である存在論は、

存在の形式的研究に焦点を当てる。したがって、存在論的なものは、存在の理解と探究、存在の根拠、あるいは存在の概念そのものに関わる。

「存在」の本質について議論する個人にとって、存在論的とは、自らの主観的な現象学的存在体験を指し得る。

|

存在論的差異

|

Ontological difference |

Ontological difference

Central to Heidegger's philosophy is the difference between being as

such and specific entities.[52][53] He calls this the "ontological

difference", and accuses the Western tradition in philosophy of being

forgetful of this distinction, which has led to misunderstanding "being

as such" as a distinct entity.[52][54][55] (See reification)

|

存在論的差異

ハイデガーの哲学の中心にあるのは、存在そのものと特定の存在物との差異である。[52][53]

彼はこれを「存在論的差異」と呼び、西洋哲学の伝統がこの区別を忘れがちだと非難する。このため「存在そのもの」が独立した実体として誤解されてきたので

ある。[52][54][55] (物象化参照)

|

| 可能性/らしさ |

Possibility |

Possibility

(German: Möglichkeit)

Möglichkeit is a term used only once in a particular edition of Being

and Time. In the text, the term appears to denote "the possibility

whose probability it is solely to be possible". At least, if it were

used in context, this is the only plausible definition.

|

可能性

(ドイツ語: Möglichkeit)

「Möglichkeit」という用語は、『存在と時間』の特定の版において一度だけ使用されている。本文中では、この用語は「単に可能であることそのも

のが確率である可能性」を指すように見える。少なくとも文脈で使用された場合、これが唯一の妥当な定義である。

|

| 手近なもの(フォアハンデルン) |

Present-at-hand |

Present-at-hand

(German: vorhanden, Vorhandenheit)

With the present-at-hand one has (in contrast to "ready-to-hand") an

attitude like that of a scientist or theorist, of merely looking at or

observing something. In seeing an entity as present-at-hand, the

beholder is concerned only with the bare facts of a thing or a concept,

as they are present and in order to theorize about it. This way of

seeing is disinterested in the concern it may hold for Dasein, its

history or usefulness. This attitude is often described as existing in

neutral space without any particular mood or subjectivity. However, for

Heidegger, it is not completely disinterested or neutral. It has a

mood, and is part of the metaphysics of presence that tends to level

all things down. Through his writings, Heidegger sets out to accomplish

the Destruktion (see above) of this metaphysics of presence.

Present-at-hand is not the way things in the world are usually

encountered, and it is only revealed as a deficient or secondary mode,

e.g., when a hammer breaks it loses its usefulness and appears as

merely there, present-at-hand. When a thing is revealed as

present-at-hand, it stands apart from any useful set of equipment but

soon loses this mode of being present-at-hand and becomes something,

for example, that must be repaired or replaced.

|

手近なもの

(ドイツ語: vorhanden, Vorhandenheit)

手近なものに対しては(「手元にあるもの」とは対照的に)、科学者や理論家のような態度、つまり単に何かを見たり観察したりする態度を持つ。ある実体を現

前として見る時、見る者は単に事物の裸の事実や概念に関心を持ち、それが現前している状態を理論化しようとする。この見方は、それがダーザイン(現存在)

にとって持つかもしれない関心や、その歴史や有用性には無関心である。この態度はしばしば、特定の気分や主体性を持たない中立的な空間に存在するものと説

明される。しかしハイデガーによれば、この態度は完全に無関心でも中立でもない。そこには気質が内在し、あらゆるものを均質化する傾向を持つ「在るものの

形而上学」の一部である。ハイデガーはその著作を通じて、この在るものの形而上学の破壊(Destruktion、前出参照)を成し遂げようとする。

手近にある状態は、世界における事物が通常遭遇される方法ではない。それは欠陥のある二次的な様態としてのみ現れる。例えば、ハンマーが壊れると、その有

用性を失い、単にそこにある、手近にあるものとして現れる。あるものが手近な存在として現れるとき、それは有用な道具としての役割から切り離されるが、す

ぐにこの手近な存在の様態を失い、例えば修理や交換を必要とするものへと変容する。 |

|

|

Ready-to-hand

This section is written like a personal reflection, personal essay, or

argumentative essay that states a Wikipedia editor's personal feelings

or presents an original argument about a topic. Please help improve it

by rewriting it in an encyclopedic style. (December 2021) (Learn how

and when to remove this message)

(German: Griffbereit, zuhanden, zuhandenheit)

In almost all cases humanity is involved in the world in an ordinary,

and more involved, way, undertaking tasks with a view to achieving

something. Take for example, a hammer: it is ready-to-hand; we use it

without theorizing. In fact, if we were to look at it as

present-at-hand, we might easily make a mistake. Only when it breaks or

something goes wrong might we see the hammer as present-at-hand, just

lying there. Even then however, it may be not fully present-at-hand, as

it is now showing itself as something to be repaired or disposed, and

therefore a part of the totality of our involvements. In this case its

Being may be seen as unreadiness-to-hand. Heidegger outlines three

manners of unreadiness-to-hand: Conspicuous (damaged; e.g., a lamp's

wiring has broken), Obtrusive (a part is missing which is required for

the entity to function; e.g., we find the bulb is missing), Obstinate

(when the entity is a hindrance to us in pursuing a project; e.g., the

lamp blocks my view of the computer screen).

Importantly, the ready-to-hand only emerges from the prior attitude in

which we care about what is going on and we see the hammer in a context

or world of equipment that is handy or remote, and that is there "in

order to" do something. In this sense the ready-to-hand is primordial

compared to that of the present-at-hand. The term primordial here does

not imply something Primitive, but rather refers to Heidegger's idea

that Being can only be understood through what is everyday and "close"

to us. Our everyday understanding of the world is necessarily a part of

any kind of scientific or theoretical studies of entities—the

present-at-hand—might be. Only by studying our "average-everyday"

understanding of the world, as it is expressed in the totality of our

relationships to the ready-to-hand entities of the world, can we lay

appropriate bases for specific scientific investigations into specific

entities within the world.

For Heidegger in Being and Time this illustrates, in a very practical

way, the way the present-at-hand, as a present in a "now" or a present

eternally (as, for example, a scientific law or a Platonic Form), has

come to dominate intellectual thought, especially since the

Enlightenment. To understand the question of being one must be careful

not to fall into this leveling off, or forgetfulness of being, that has

come to assail Western thought since Socrates, see the metaphysics of

presence.

|

手近にある

この節は、ウィキペディア編集者の個人的な感想や、主題に関する独自の主張を述べる個人的な考察、エッセイ、論説のように書かれている。百科事典的なスタ

イルで書き直すことで改善に協力してほしい。(2021年12月) (このメッセージを削除する方法と時期について)

(ドイツ語: Griffbereit, zuhanden, zuhandenheit)

ほとんどの場合、人類は世界と普通かつより深く関わり、何かを達成する目的で作業を行う。例えばハンマーを考えよう。それは手近にある。我々は理論化せず

にそれを使う。実際、それを「眼前にあるもの」として見れば、間違いを犯しやすい。壊れたり何か問題が起きた時だけ、ハンマーを「現前する」ものとして、

ただそこにあるものとして見るかもしれない。しかしその場合でさえ、完全に「現前する」とは限らない。なぜならそれは今や、修理や廃棄の対象として現れて

おり、したがって我々の関与の全体性の一部となっているからだ。この場合、その存在は「手近でない状態」と見なされるかもしれない。ハイデガーは「手近で

ない状態」の三つの様態を概説している:

顕在的(損傷状態;例:ランプの配線が切れている)、侵入的(機能に必要な部品が欠けている状態;例:電球がないことに気づく)、妨害的(ある物事が計画

の遂行を妨げる状態;例:ランプがコンピューター画面の視界を遮る)。

重要なのは、手近なものは、まず我々が周囲の状況に関心を持ち、ハンマーを「何かを行うために」存在する道具や装置の世界・文脈の中で認識する態度から初

めて現れるということだ。この意味で、手近なものは手元にあるものよりも原初的だ。ここで言う原初的とは原始的な意味ではなく、ハイデガーの「存在は日常

的で身近なものを通じてのみ理解できる」という思想を指す。我々の日常的世界理解は、あらゆる科学的・理論的実体研究―手元にあるもの―の必然的基盤であ

る。世界の「手近にあるもの」群との関係性全体に表れる「平均的な日常的」世界理解を研究することによってのみ、世界内の特定実体に対する科学的探究の適

切な基盤を築けるのだ。

ハイデガーは『存在と時間』において、このことが非常に実践的な形で示していると論じる。すなわち「今」における現在性、あるいは永遠的な現在性(例えば

科学的法則やプラトンのイデアとして)としての「手近な存在」が、特に啓蒙主義以降、知的思考を支配するに至った過程を。存在の問題を理解するには、ソク

ラテス以来西洋思想を襲ってきたこの平準化、あるいは存在の忘却に陥らないよう注意しなければならない。存在のメタフィジックスを参照せよ。

|

| 断固たる決意 |

Resoluteness |

Resoluteness

(German: Entschlossenheit)

Resoluteness refers to one's ability to "unclose" one's framework of

intelligibility (i.e., to make sense of one's words and actions in

terms of one's life as a whole), and the ability to be receptive to the

"call of conscience".

|

断固たる決意

(ドイツ語: Entschlossenheit)

断固たる決意とは、自らの理解の枠組みを「開く」能力(すなわち、自らの言葉や行動を人生全体という観点から意味づけられる能力)を指す。また「良心の呼

びかけ」に耳を傾ける能力でもある。

|

| 存在の忘却(ザインスフェルゲゼッセンハイト) |

Seinsvergessenheit |

Seinsvergessenheit

Seinsvergessenheit is translated variously as "forgetting of being" or

"oblivion of being". A closely related term is Seinsverlassenheit,

translated as "abandonment of being". Heidegger believed that a

pervasive nihilism in the modern world stems from

Seinsverlassenheit.[56] The "ontological difference," the distinction

between being (Sein) and beings (das Seiende), is fundamental for

Heidegger. The forgetfulness of being that, according to him, occurs in

the course of Western philosophy amounts to the oblivion of this

distinction.[57] |

存在の忘却

存在の忘却は「存在の忘却」あるいは「存在の忘却」と訳される。密接に関連する用語として存在の放棄があり、これは「存在の放棄」と訳される。ハイデガー

は、現代世界に蔓延するニヒリズムは存在の放棄に起因すると考えた[56]。存在(Sein)と存在物(das

Seiende)の区別である「存在論的差異」はハイデガーにとって根本的な概念である。西洋哲学の過程で生じたとされる存在の忘却は、この区別の忘却に

他ならない[57]。

|

| 一人/彼ら |

The One / the They |

The One / the They

(German: Das Man, meaning "they-self")

One of the most interesting and important 'concepts' in Being and Time

is that of Das Man, for which there is no exact English translation;

different translations and commentators use different conventions. It

is often translated as "the They" or "People" or "Anyone" but is more

accurately translated as "One" (as in "'one' should always arrive on

time"). Jan Patočka denoted for the concept Das Man a synonymous

designation "public anonymous". Das Man derives from the impersonal

singular pronoun man ('one', as distinct from 'I', or 'you', or 'he',

or 'she', or 'they'). Both the German man and the English 'one' are

neutral or indeterminate in respect of gender and, even, in a sense, of

number, though both words suggest an unspecified, unspecifiable,

indeterminate plurality. The semantic role of the word man in German is

nearly identical to that of the word one in English.

Heidegger refers to this concept of the One in explaining inauthentic

modes of existence, in which Dasein, instead of truly choosing to do

something, does it only because "That is what one does" or "That is

what people do". Thus, das Man is not a proper or measurable entity,

but rather an amorphous part of social reality that functions

effectively in the manner that it does through this intangibility.

Das Man constitutes a possibility of Dasein's Being, and so das Man

cannot be said to be any particular someone. Rather, the existence of

'the They' is known to us through, for example, linguistic conventions

and social norms. Heidegger states that, "The 'they' prescribes one's

state-of-mind, and determines what and how one 'sees'."

To give examples: when one makes an appeal to what is commonly known,

one says "one does not do such a thing"; When one sits in a car or bus

or reads a newspaper, one is participating in the world of 'the They'.

This is a feature of 'the They' as it functions in society, an

authority that has no particular source. In a non-moral sense Heidegger

contrasts "the authentic self" ("my owned self") with "the they self"

("my un-owned self").

A related concept to this is that of the apophantic assertion.

|

一人/彼ら

(ドイツ語:Das Man、「彼ら自身」を意味する)

『存在と時間』における最も興味深く重要な概念の一つがDas

Manである。これに正確な英語訳はなく、翻訳者や解説者によって異なる慣例が使われる。しばしば「彼ら」や「人民」、「誰か」と訳されるが、より正確に

は「一人」(例:「『一人』は常に時間通りに到着すべきだ」)と訳される。ヤン・パトチェカはこの概念に対し「公的な匿名者」という同義の呼称を与えた。

ダス・マンは、非人称単数代名詞「man」(「一人」を意味し、「私」や「あなた」、「彼」、「彼女」、「彼ら」とは区別される)に由来する。ドイツ語の

manも英語のoneも、性別に関して中立的あるいは不確定であり、ある意味では数についても不確定である。ただし両語とも、特定されない、特定不可能

な、不確定な複数性を暗示している。ドイツ語のmanと英語のoneの語義的役割はほぼ同一である。

ハイデガーはこの「一人」の概念を用いて、不本意な存在様態を説明する。ダーザインが真に選択して行動する代わりに、「そういうものだから」「皆がそうす

るから」という理由で行動する状態を指す。したがって、ダス・マンは実体として測定可能な存在ではなく、むしろ社会的現実の不定形な一部であり、この無形

性によって効果的に機能する。

ダス・マンはダーザイン(現存在)の在り方の可能性を構成するため、特定の誰かであるとは言えない。むしろ「彼ら」の存在は、例えば言語慣習や社会的規範

を通じて我々に知られる。ハイデガーは言う。「『彼ら』は人の心の状態を規定し、人が何をどのように『見る』かを決定する」と。

例を挙げよう:人が常識に訴える時、「そんなことはしないものだ」と言う。車やバスに乗ったり新聞を読んだりする時、人は『彼ら』の世界に参加しているの

だ。これは社会で機能する「彼ら」の特徴であり、特定の源を持たない権威である。非道徳的な意味でハイデガーは「本物の自己」(「私の所有された自己」)

と「彼らとしての自己」(「私の所有されていない自己」)を対比させる。

これに関連する概念が否定的な断言である。 |

世界

|

World |

World

(German: Welt)

Further information: World disclosure

Heidegger gives us four ways of using the term world:

1. "World" is used as an ontical concept, and signifies the totality or

aggregate (Inwood) of things (entities) which can be present-at-hand

within the world.

2. "World" functions as an ontological term, and signifies the Being of

those things we have just mentioned. And indeed 'world' can become a

term for any realm which encompasses a multiplicity of entities: for

instance, when one talks of the 'world' of a mathematician, 'world'

signifies the realm of possible objects of mathematics.

3. "World" can be understood in another ontical sense—not, however, as

those entities which Dasein essentially is not and which can be

encountered within-the-world, but rather as the wherein a factical

Dasein as such can be said to 'live'. "World" has here a

pre-ontological existentiell signification. Here again there are

different possibilities: "world" may stand for the 'public' we-world,

or one's 'own' closest (domestic) environment.

4. Finally, "world" designates the ontologico-existential concept of

worldhood (Weltheit). Worldhood itself may have as its modes whatever

structural wholes any special 'worlds' may have at the time; but it

embraces in itself the a priori character of worldhood in general.[58]

Note, it is the third definition that Heidegger normally uses.

|

世界

(ドイツ語: Welt)

詳細情報: 世界の開示

ハイデガーは「世界」という用語を四つの用法で用いる:

1. 「世界」は存在論的概念として用いられ、世界内に現前し得る事物(実体)の総体または集合(インウッド)を意味する.

2.

「世界」は存在論的用語として機能し、前述の諸ものの存在を意味する。実際「世界」は、多様な実体を包含するあらゆる領域を指す用語となり得る。例えば数

学者の「世界」について語る場合、「世界」は数学の可能な対象の領域を意味する。

3.

「世界」は別の存在論的意味でも理解できる。ただし、それは存在者(ダーザイン(現存在)が本質的に非在するものであり、世界内に遭遇し得る実体としてで

はなく、むしろ事実的な存在者(ダーザイン(現存在)そのものが「生きる」と言える場としてである。ここでの「世界」は存在論以前の実存的意味を持つ。こ

こでもまた異なる可能性がある。「世界」は『公的な』われわれの世界を指すこともあれば、個人の『私的な』最も身近な(家庭的な)環境を指すこともある。

4.

最後に、「世界」は存在論的・実存的な世界性(ウェルツァイト)の概念を指す。世界性そのものは、特定の「世界」が持つ構造的全体性をその様態として持つ

かもしれないが、世界性一般のア・プリオリな性格を内包している。[58]

注意:ハイデガーが通常用いるのは第三の定義である。 |

|

|

Dahlstrom, Daniel O. (7 February

2013). The

Heidegger Dictionary. London: A & C Black. ISBN

978-1-847-06514-8.

Munday, Roderick (March 2009). "Glossary

of Terms in Being and Time".

|

ダールストロム、ダニエル・O. (2013年2月7日).

『ハイデガー辞典』. ロンドン: A & C ブラック. ISBN 978-1-847-06514-8.

マンデイ、ロデリック (2009年3月). 「存在と時間における用語集」.

|

|

|

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Heideggerian_terminology

|

|

☆

☆