ラテンアメリカの文化

Culture of Latin America

LATIN AMERICA. from Encyclopedia of Latin American history and

culture, 2008.

"Latin America, term commonly used to describe South America, Central America, Mexico, and the islands of the Caribbean. As such, it incorporates numerous Spanish-speaking countries, Portuguese-speaking Brazil, French-speaking Haiti and the French West Indies, and usually implies countries such as Suriname and Guyana, where Romance languages are not spoken. The term Latin America originated in France during the reign of Napoleon III [1808-1873]in the 1860s, when the country was second only to England in terms of industrial and financial strength. The French political economist Michel Chevalier [1806-1879], in an effort to solidify the intellectual underpinnings of French overseas ambitions, first proposed a "Pan-Latin" foreign policy in the hopes of promoting solidarity between nations whose languages were of Latin origin and that shared the common cultural tradition of Roman Catholicism. Led by France, the Latin peoples could reassert their influence throughout the world in the face threats from both the Slavic peoples of eastern Europe (led by Russia) and the Anglo-Saxon peoples of northern Europe (led by England). In the Western Hemisphere, Pan-Latinists distinguished between the Anglo north and the Latin south, which they gradually began to refer to as América latina. From the French l'Amérique Latino, the term came into general use in other languages."

「ラテンアメリカという用語は一般的に、南アメリ

カ、中央アメリカ、メキシコ、カリブ海の島々を指すために使用される。そのため、ラテンアメリカには多数のスペイン語圏の国々、ポルトガル語を話すブラジ

ル、フランス語を話すハイチおよびフランス領西インド諸島が含まれ、通常はロマンス諸語が話されていないスリナムやガイアナなどの国々も含まれる。ラテン

アメリカという用語は、1860年代に産業および金融の面でイギリスに次ぐ強国であったナポレオン3世(1808-1873)の治世下のフランスで生まれ

た。フランスの政治経済学者ミシェル・シュヴァリエ(1806-1879)は、フランスの海外進出の野望を支える知的基盤を強化しようと、ラテン語を起源

とする言語を話し、ローマ・カトリックという共通の文化伝統を持つ諸国民の連帯を促進することを期待して、初めて「汎ラテン」外交政策を提唱した。フラン

スが主導するラテン民族は、ロシア率いる東ヨーロッパのスラブ民族と、イギリス率いる北ヨーロッパのアングロサクソン民族の双方からの脅威に直面する中、

世界中で再びその影響力を主張することができた。西半球において、汎ラテン主義者たちはアングロ系の北とラテン系の南を区別し、徐々に「ラテンアメリカ」

という名称で呼ぶようになった。この名称は、フランス語の「ラテンアメリカ」から、他の言語でも一般的に使用されるようになった」(→「ラテンアメリカという概念」「ラテンアメリカのポピュラーカルチャー」)

★本質主義を前提にした"Culture of Latin America"の記事

| The

culture of Latin America is the formal or informal expression of

the people of Latin America and includes both high culture (literature

and high art) and popular culture (music, folk art, and dance), as well

as religion and other customary practices. These are generally of

Western origin, but have various degrees of Native American, African

and Asian influence. Definitions of Latin America vary. From a cultural perspective,[1] Latin America generally refers to those parts of the Americas whose cultural, religious and linguistic heritage can be traced to the Latin culture of the late Roman Empire. This would include areas where Spanish, Portuguese, and various other Romance languages, which can trace their origin to the Vulgar Latin spoken in the late Roman Empire, are natively spoken. Such territories include almost all of Mexico, Central America and South America, with the exception of English or Dutch speaking territories. Culturally, it could also encompass the French derived culture in the Caribbean and North America, as it ultimately derives from Latin Roman influence as well. There is also an important Latin American cultural presence in the United States since the 16th century in areas such as California, Texas, and Florida, which were part of the Spanish Empire. More recently, in cities such as New York, Chicago, Dallas, Los Angeles, and Miami. The richness of Latin American culture is the product of many influences, including: Spanish and Portuguese culture, owing to the region's history of colonization, settlement and continued immigration from Spain and Portugal. All the core elements of Latin American culture are of Iberian origin, which is ultimately related to Western culture. Pre-Columbian cultures, whose importance is today particularly notable in countries such as Mexico, Guatemala, Ecuador, Peru, Bolivia, and Paraguay. These cultures are central to Indigenous communities such as the Quechua, Maya, and Aymara. 19th- and 20th-century European immigration from Spain, Portugal, Italy, Germany, France, and Eastern Europe; which transformed the region and had an impact in countries such as Argentina, Peru, Uruguay, Brazil (particular the southeast and southern regions), Colombia, Cuba, Chile, Venezuela, Ecuador (particularly in the southwest coast), Paraguay, Dominican Republic (specifically the northern region), and Mexico (particularly the northern and western regions). Chinese, Japanese, Korean, Indian, Lebanese and other Arab, Armenian and various other Asian groups. Mostly immigrants and indentured laborers who arrived from the coolie trade and influenced the culture of Brazil, Colombia, Cuba, Panama, Nicaragua, Ecuador and Peru in areas such as food, art, and cultural trade. The culture of Africa brought by Africans in the Trans-Atlantic former slave trade has influenced various parts of Latin America. Influences are particularly strong in dance, music, cuisine, and some syncretic religions of Cuba, Brazil, Dominican Republic, Venezuela, Northwest Ecuador, coastal Colombia, and Honduras.[2][3][4] |

ラテンアメリカの文化とは、ラテンアメリカの人々の公式または非公式な

表現であり、高尚な文化(文学や高尚な芸術)とポピュラー・カルチャー(音楽、民俗芸術、舞踊)の両方を含む。また宗教やその他の慣習的な実践も含まれ

る。これらは一般的に西洋起源であるが、先住民、アフリカ、アジアの影響を様々な程度で受けている。 ラテンアメリカの定義は様々である。文化的観点から[1]、ラテンアメリカとは一般的に、文化的・宗教的・言語的遺産が後期ローマ帝国のラテン文化に遡れ るアメリカ大陸の地域を指す。これには、後期ローマ帝国で話されていた俗ラテン語に起源を持つスペイン語、ポルトガル語、その他のロマンス語族が母語とし て話される地域が含まれる。こうした地域には、英語やオランダ語圏を除いたメキシコ、中央アメリカ、南アメリカのほぼ全域が含まれる。文化的には、カリブ 海や北米におけるフランス由来の文化も包含し得る。これらも究極的にはラテン・ローマの影響に由来するからだ。また、16世紀以降、カリフォルニア、テキ サス、フロリダといったスペイン帝国の一部であった地域では、米国における重要なラテンアメリカ文化の存在感がある。近年では、ニューヨーク、シカゴ、ダ ラス、ロサンゼルス、マイアミといった都市でも同様だ。 ラテンアメリカ文化の豊かさは、多くの影響の産物である。具体的には: スペインとポルトガルの文化。これは地域の植民地化、入植、そしてスペイン・ポルトガルからの継続的な移民の歴史に起因する。ラテンアメリカ文化の中核的 要素は全てイベリア半島に起源を持ち、究極的には西洋文化と関連している。 コロンブス以前の文化は、今日特にメキシコ、グアテマラ、エクアドル、ペルー、ボリビア、パラグアイなどの国々で重要性が顕著だ。これらの文化はケチュア 族、マヤ族、アイマラ族などの先住民コミュニティの中核をなしている。 19世紀から20世紀にかけてのスペイン、ポルトガル、イタリア、ドイツ、フランス、東欧からのヨーロッパ移民。この移民は地域を変容させ、アルゼンチ ン、ペルー、ウルグアイ、ブラジル(特に南東部と南部地域)、コロンビア、キューバ、チリ、ベネズエラ、エクアドル(特に南西海岸)、パラグアイ、ドミニ カ共和国(特に北部地域)、メキシコ(特に北部と西部地域)などの国々に影響を与えた。(特に北部と西部地域)。 中国人、日本人、韓国人、インド人、レバノン人およびその他のアラブ人、アルメニア人、その他様々なアジア系集団。主にクーリー貿易によって到着した移民 や契約労働者であり、ブラジル、コロンビア、キューバ、パナマ、ニカラグア、エクアドル、ペルーの食文化、芸術、文化交流などの分野に影響を与えた。 大西洋奴隷貿易によってアフリカ人が持ち込んだアフリカ文化は、ラテンアメリカの様々な地域に影響を与えた。特にキューバ、ブラジル、ドミニカ共和国、ベ ネズエラ、エクアドル北西部、コロンビア沿岸部、ホンジュラスでは、舞踊、音楽、料理、そしていくつかのシンクレティズム宗教においてその影響が顕著であ る。[2][3][4] |

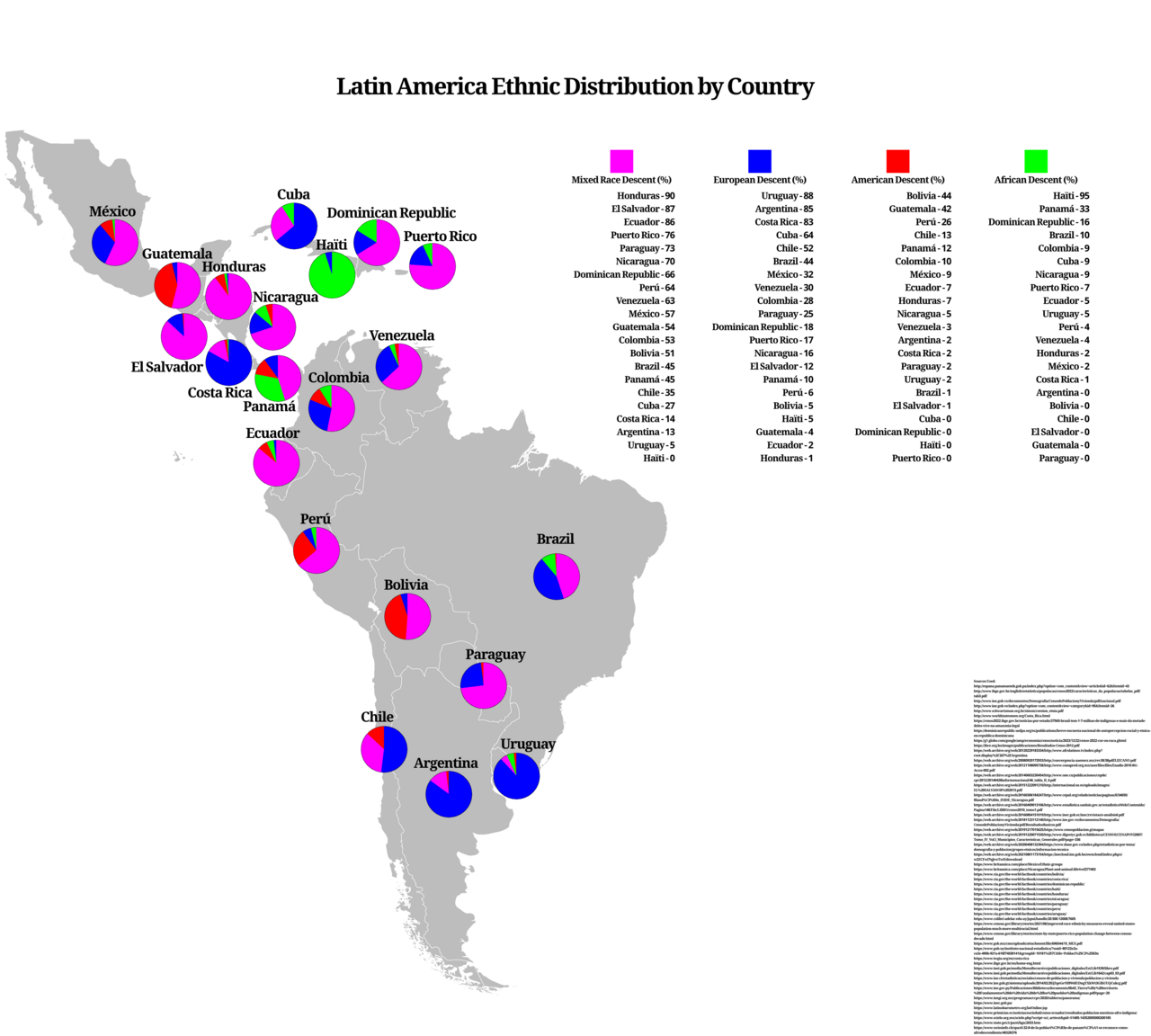

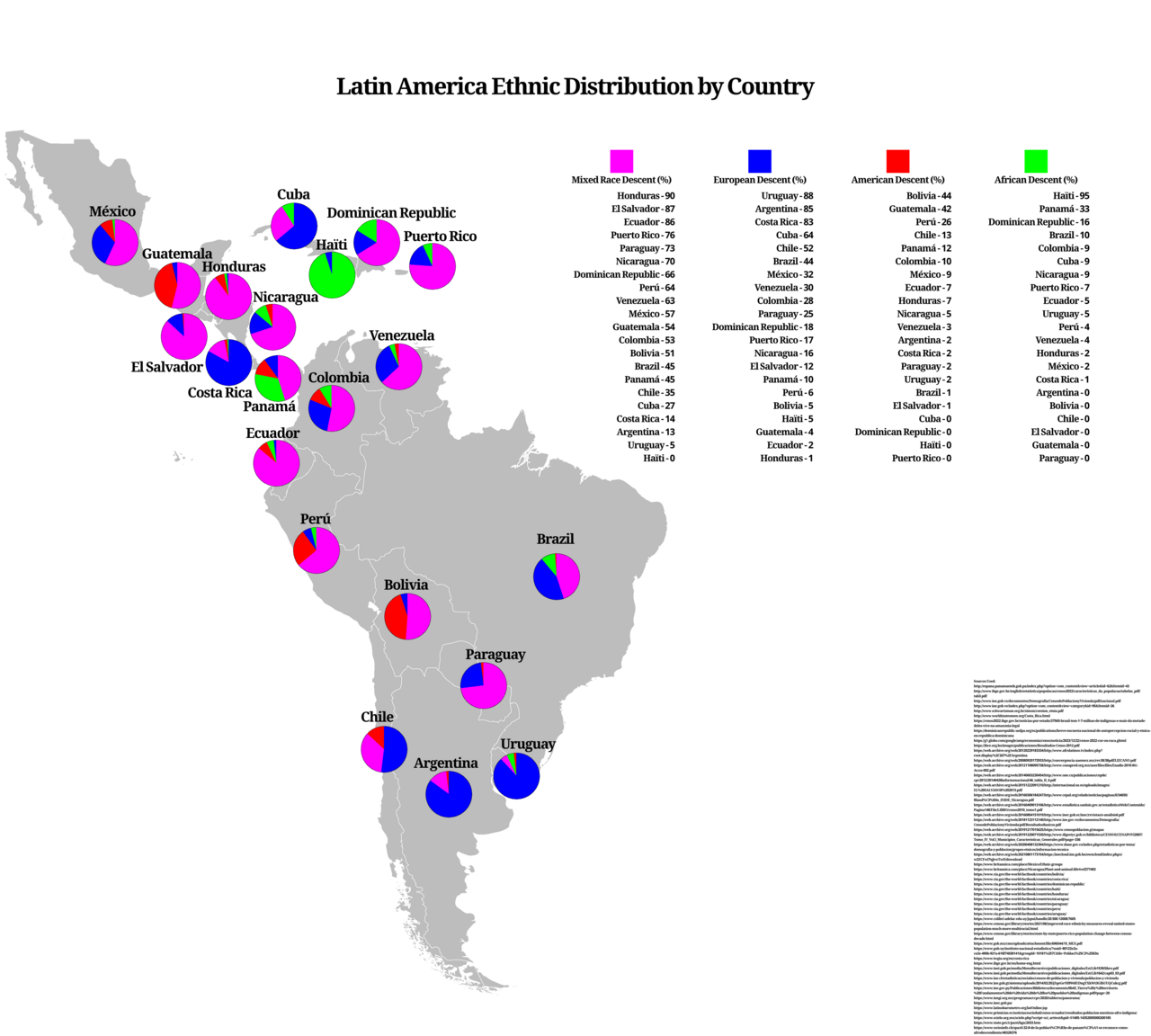

| Ethnic groups Main article: Ethnic groups in Latin America  Ethnic distribution by country. The population of Latin America is very diverse with many ethnic groups and different ancestries. Most of the Amerindian descendants are of mixed race ancestry.[citation needed] In the 16th, 17th and 18th centuries there was a flow of Spanish and Portuguese emigrants who left for Latin America. It was never a large movement of people, but over the long period of time it had a major impact on Latin American populations: the Portuguese left for Brazil and the Spaniards left for Central and South America. Of the European immigrants, men greatly outnumbered women and many married Natives. This resulted in a mixing of the Amerindians and Europeans and today their descendants are known as mestizos. Even Latin American criollos, of mainly European ancestry, usually have some Native ancestry. Today, mestizos make up the majority of Latin America's population. Starting in the late 16th century, a large number of former African slaves were brought to Latin America, especially to Brazil and the Caribbean.[citation needed] Nowadays, blacks make up the majority of the population in most Caribbean countries. Many of the former African slaves in Latin America mixed with the Europeans and their descendants (known as mulattoes) make up the majority of the population in some countries, such as the Dominican Republic, and large percentages in Brazil, Colombia, and Honduras.[5][6][4] Mixes between the blacks and Amerindians also occurred, and their descendants are known as zambos. Many Latin American countries also have a substantial tri-racial population known as pardos, whose ancestry is a mix of Amerindians, Europeans and Africans.[citation needed] Large numbers of European immigrants arrived in Latin America in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, most of them settling in the Southern Cone (Argentina, Uruguay, and southern Brazil).[citation needed] Nowadays the Southern Cone has a majority of people of largely European descent and in all more than 80% of Latin America's European population, which is mostly descended from six groups of immigrants: Italians, Spaniards, Portuguese, French, Germans, Jews (both Ashkenazi and Sephardic) and, to a lesser extent, Irish, Poles, Greeks, Croats, Russians, Welsh, Ukrainians, etc.[citation needed] In this same period, immigrants came from the Middle East and Asia, including Indians, Lebanese, Syrians, Armenians, and, more recently, Koreans, Chinese and Japanese, mainly to Brazil. These people only make up a small percentage of Latin America's population but they have communities in the major cities. This diversity has profoundly influenced religion, music and politics. This cultural heritage is called Latino in American English. |

民族グループ 主な記事: ラテンアメリカの民族グループ  国別の民族分布。 ラテンアメリカの人口は多様で、多くの民族グループと異なる祖先を持つ。アメリカ先住民の子孫の大半はミヘの祖先を持つ。[出典が必要] 16世紀、17世紀、18世紀には、スペインとポルトガルの移民がラテンアメリカへ流れ込んだ。大規模な人口移動ではなかったが、長い期間にわたってラテ ンアメリカの人口構成に重大な影響を与えた。ポルトガル人はブラジルへ、スペイン人は中南米へ移住した。ヨーロッパからの移民では男性が女性を大幅に上回 り、多くの者が先住民と結婚した。これによりアメリカ先住民とヨーロッパ人の混血のが生じ、今日ではその子孫はメスティーソとして知られている。主にヨー ロッパ系の祖先を持つラテンアメリカのクリオージョでさえ、通常は先住民の血を引いている。今日、メスティソはラテンアメリカ人口の大多数を占めている。 16世紀後半から、多くの元アフリカ人奴隷がラテンアメリカ、特にブラジルとカリブ海地域に連れてこられた。現在、カリブ海のほとんどの国では黒人が人口 の大多数を占めている。ラテンアメリカにおける元アフリカ人奴隷の多くはヨーロッパ人と混血の関係を結んでおり、その子孫(ムラートと呼ばれる)はドミニ カ共和国などの一部国家では人口の大多数を占め、ブラジル、コロンビア、ホンジュラスでも大きな割合を占めている。[5][6][4] 黒人とアメリカ先住民の間の混血も発生し、その子孫はサンボとして知られている。多くのラテンアメリカ諸国には、先住民、ヨーロッパ人、アフリカ人の混血 の「パルド」と呼ばれる三つの人種に属する人々も相当数存在する。[出典が必要] 19世紀末から20世紀初頭にかけて、多くのヨーロッパ移民がラテンアメリカに流入し、その大半は南米南部(アルゼンチン、ウルグアイ、ブラジル南部)に 定住した。[出典が必要] 現在、南コーン地域では人口の大半が主にヨーロッパ系であり、ラテンアメリカ全体のヨーロッパ系人口の80%以上を占める。その祖先は主に6つの移民グ ループに由来する:イタリア人、スペイン人、ポルトガル人、フランス人、ドイツ人、ユダヤ人(アシュケナージ系とセファルディ系の両方)、そしてより少数 ながらアイルランド人、ポーランド人、ギリシャ人、クロアチア人、ロシア人、ウェールズ人、ウクライナ人などである。[出典が必要] 同時期に中東やアジアからも移民が流入した。インド人、レバノン人、シリア人、アルメニア人、そして近年では韓国人、中国人、日本人が主にブラジルへ移住 した。これらの人々はラテンアメリカ人口のごく一部に過ぎないが、主要都市にはコミュニティを形成している。 この多様性は宗教、音楽、政治に深い影響を与えた。この文化的遺産はアメリカ英語で「ラティーノ」と呼ばれる。 |

Language Romance languages in Latin America: Green-Spanish; Orange-Portuguese; Blue-French Spanish is spoken in Puerto Rico and eighteen sovereign nations (See Spanish language in the Americas). Portuguese is spoken primarily in Brazil (See Brazilian Portuguese). Amerindian languages are spoken in many Latin American nations, mainly Chile, Panama, Ecuador, Colombia, Guatemala, Bolivia, Paraguay, Argentina, and Mexico. Nahuatl has more than a million speakers in Mexico. Although Mexico has almost 80 native languages across the country, the government nor the constitution specify an official language (not even Spanish), also, some regions of the nation do not speak any modern way of language and still preserve their ancient dialect without knowing any other language. Guaraní is, along with Spanish, the official language of Paraguay, and is spoken by a majority of the population. Furthermore, there are about 10 million Quechua speakers in South America and Spain, but more than half of them live in Bolivia and Peru (approximately 6,700,800 individuals). Other European languages spoken include Italian in Brazil and Uruguay, German in southern Brazil and southern Chile, and Welsh in southern Argentina. |

言語 ラテンアメリカにおけるロマンス語:緑-スペイン語;オレンジ-ポルトガル語;青-フランス語 スペイン語はプエルトリコと18の独立国で話されている(アメリカ大陸におけるスペイン語参照)。ポルトガル語は主にブラジルで話されている(ブラジルポ ルトガル語参照)。アメリカ先住民言語は多くのラテンアメリカ国民で話されている。主にチリ、パナマ、エクアドル、コロンビア、グアテマラ、ボリビア、パ ラグアイ、アルゼンチン、メキシコだ。ナワトル語はメキシコで100万人以上の話者がいる。メキシコには国内に約80の先住民言語が存在するが、政府も憲 法も公用語を定めていない(スペイン語すらも)。また、一部の国民地域では現代的な言語を一切話さず、他の言語を知らずに古代の方言を今も維持している。 グアラニー語はスペイン語と共にパラグアイの公用語であり、人口の大半が話す。さらに南米とスペインには約1000万人のケチュア語話者がいるが、その半 数以上がボリビアとペルーに居住している(約670万人)。 その他のヨーロッパ系言語としては、ブラジルとウルグアイで話されるイタリア語、ブラジル南部とチリ南部で話されるドイツ語、アルゼンチン南部で話される ウェールズ語がある。 |

| Religion Main article: Religion in Latin America  The Basilica of the National Shrine of Our Lady of Aparecida is the second largest in the world, after only of the Basilica of Saint Peter in Vatican City.[7] The primary religion throughout Latin America is Christianity (90%),[8] mostly Roman Catholicism.[9][10] Latin America, and in particular Brazil, were active in developing the quasi-socialist Roman Catholic movement known as Liberation Theology.[11] Practitioners of the Protestant, Pentecostal, Evangelical, Jehovah's Witnesses, Mormon, Buddhist, Jewish, Muslim, Hindu, Baháʼí, and indigenous denominations and religions exist. Various Afro-Latin American traditions, such as Santería, and Macumba, a tribal- voodoo religion, are also practiced. Evangelicalism in particular is increasing in popularity.[12] Latin America constitute in absolute terms the second world's largest Christian population, after Europe.[13] |

宗教 詳細な記事: ラテンアメリカの宗教  アパレシダの聖母国家聖堂は、バチカン市国のサン・ピエトロ大聖堂に次いで世界で2番目に大きい聖堂である。[7] ラテンアメリカ全域における主要な宗教はキリスト教(90%)であり、[8]その大部分はローマ・カトリックである。[9][10] ラテンアメリカ、特にブラジルは、解放の神学として知られる準社会主義的なローマカトリック運動の発展に積極的に関わった。[11] プロテスタント、ペンテコステ派、福音派、エホバの証人、モルモン教、仏教、ユダヤ教、イスラム教、ヒンドゥー教、バハーイー教、先住民の宗派や宗教の信 者も存在する。サンテリアや部族系ヴードゥー教であるマクンバなど、様々なアフロ・ラテンアメリカの伝統も実践されている。特に福音主義の人気が高まって いる。[12] ラテンアメリカは絶対数において、ヨーロッパに次いで世界で2番目に大きなキリスト教人口を構成している。[13] |

| Folklore Further information: Folk Catholicism Further information: Colombian folklore Further information: Category:Brazilian folklore Further information: Category:Mexican folklore Further information: Category:Peruvian folklore See also: Cuento |

民俗学 詳細情報: 民俗カトリック 詳細情報: コロンビアの民俗学 詳細情報: カテゴリ:ブラジルの民俗学 詳細情報: カテゴリ:メキシコの民俗学 詳細情報: カテゴリ:ペルーの民俗学 関連項目: クエント |

| Arts and leisure Further information: Latin America–United Kingdom relations In long-term perspective, Britain's influence in Latin America was enormous after independence came in the 1820s. Britain deliberately sought to replace the Spanish and Portuguese in economic and cultural affairs. Military issues and colonization were minor factors. The influence was exerted through diplomacy, trade, banking, and investment in railways and mines. The English language and British cultural norms were transmitted by energetic young British business agents on temporary assignment in the major commercial centers, where they invited locals into the British leisure activities, such as organized sports, and into their transplanted cultural institutions such as schools and clubs. The British role never disappeared, but it faded rapidly after 1914 as the British cashed in their investments to pay for the Great War, and the United States, another Anglophone power, moved into the region with overwhelming force and similar cultural norms.[14] Sports Further information: History of sport in Latin America and Sport in South America The British impact on sports was overwhelming, as Latin America took up football (called fútbol in Spanish and futebol in Portuguese). In Argentina, rugby, polo, tennis and golf became important middle-class leisure pastimes.[15]  Plaquita, a Dominican street version of cricket. The Dominican Republic was first introduced to cricket through mid-18th century British contact,[16] but switched to baseball after the 1916 American occupation.[17] In some parts of the Caribbean and Central America baseball outshined soccer in terms of popularity. The sport started in the late 19th century when sugar companies imported cane cutters from the British Caribbean. During their free time, the workers would play cricket, but later, during the long period of US military occupation, cricket gave way to baseball, which rapidly assumed widespread popularity, although cricket remains the favorite in the British Caribbean. Baseball had the greatest following in those nations occupied at length by the US military, especially the Dominican Republic and Cuba, as well as Nicaragua, Panama, and Puerto Rico. Even Venezuela, which wasn't occupied by the US military during this time period, still became a popular baseball destination. All of these countries have emerged as sources of baseball talent, since many players hone their skills on local teams, or in “academies” managed by the US Major Leagues to cultivate the most promising young men for their own teams.[18] Baseball5, an official variation of baseball, was inspired in 2017 by Latin American street variations of baseball as well.[19] |

芸術と余暇 詳細情報:ラテンアメリカとイギリスの関係 長期的な視点で見ると、1820年代に独立が実現した後、イギリスのラテンアメリカにおける影響力は非常に大きかった。英国は熟議によって、経済・文化分 野でスペインやポルトガルの地位を置き換えようとした。軍事問題や植民地化は副次的な要素だった。その影響力は外交、貿易、銀行業、鉄道や鉱山への投資を 通じて発揮された。英語と英国の文化的規範は、主要商業都市に一時派遣された精力的な英国人ビジネスエージェントによって伝播された。彼らは現地人を組織 的なスポーツなどの英国式レジャー活動や、学校やクラブといった移植された文化施設に招き入れた。英国の役割は消えなかったが、1914年以降は急速に衰 退した。英国が第一次世界大戦費用を賄うため投資を現金化した一方で、もう一つの英語圏大国である米国が圧倒的な軍事力と類似の文化的規範をもってこの地 域に進出したためである。[14] スポーツ 詳細情報: ラテンアメリカにおけるスポーツの歴史、南アメリカのスポーツ スポーツへの英国の影響は圧倒的だった。ラテンアメリカがサッカー(スペイン語でフートボール、ポルトガル語でフェイサル)を取り入れたからだ。アルゼン チンではラグビー、ポロ、テニス、ゴルフが中産階級の重要な娯楽となった。[15]  プラキータ(Plaquita)は、ドミニカ共和国でクリケットを街中で簡略化した遊びである。同国では18世紀半ばの英国との接触を通じてクリケットが 導入されたが[16]、1916年の米国占領後に野球へと移行した。[17] カリブ海及び中央アメリカの一部地域では、野球がサッカーの人気を上回った。このスポーツは19世紀末、砂糖会社が英領カリブからサトウキビ刈り労働者を 輸入した際に始まった。労働者たちは余暇にクリケットをプレイしたが、その後、長期にわたる米軍占領期にクリケットは野球に取って代わられ、野球は急速に 広範な人気を獲得した。ただし英領カリブではクリケットが依然として人気を保っている。野球が最も支持を集めたのは、米軍による長期占領を受けた国民、特 にドミニカ共和国やキューバ、さらにニカラグア、パナマ、プエルトリコであった。この期間に米軍占領を受けなかったベネズエラでさえ、野球の人気拠点と なった。これらの国々は全て、野球選手の供給源として台頭した。多くの選手が地元のチームや、メジャーリーグが運営する「アカデミー」で技術を磨き、有望 な若者を自チームに育成するためだ[18]。また2017年には、ラテンアメリカの路上野球の変種に着想を得た公式ルール「ベースボール5」も誕生した [19]。 |

| Literature Main article: Latin American literature See also: List of Latin American writers Pre-Columbian cultures were primarily oral, though the Aztecs and Mayans, for instance, produced elaborate codices. Oral accounts of mythological and religious beliefs were also sometimes recorded after the arrival of European colonizers, as was the case with the Popol Vuh. Moreover, a tradition of oral narrative survives to this day, for instance among the Quechua-speaking population of Peru and the Quiché of Guatemala. From the very moment of Europe's "discovery" of the continent, early explorers and conquistadores produced written accounts and crónicas of their experience—such as Columbus's letters or Bernal Díaz del Castillo's description of the conquest of New Spain. During the colonial period, written culture was often in the hands of the church, within which context Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz wrote memorable poetry and philosophical essays. Towards the end of the 18th century and the beginning of the 19th, a distinctive criollo literary tradition emerged, including the first novels such as Lizardi's El Periquillo Sarniento (1816). The 19th century was a period of "foundational fictions" (in critic Doris Sommer's words), novels in the Romantic or Naturalist traditions that attempted to establish a sense of national identity, and which often focussed on the indigenous question or the dichotomy of "civilization or barbarism" (for which see, say, Domingo Sarmiento's Facundo (1845), Juan León Mera's Cumandá (1879), or Euclides da Cunha's Os Sertões (1902)). At the turn of the 20th century, modernismo emerged, a poetic movement whose founding text was Rubén Darío's Azul (1888). This was the first Latin American literary movement to influence literary culture outside of the region, and was also the first truly Latin American literature, in that national differences were no longer so much at issue.[citation needed] José Martí, for instance, though a Cuban patriot, also lived in Mexico and the United States and wrote for journals in Argentina and elsewhere. However, what really put Latin American literature on the global map was no doubt the literary boom of the 1960s and 1970s,[citation needed] distinguished by daring and experimental novels (such as Julio Cortázar's Rayuela (1963)) that were frequently published in Spain and quickly translated into English. The Boom's defining novel was Gabriel García Márquez's Cien años de soledad (1967), which led to the association of Latin American literature with magic realism, though other important writers of the period such as Mario Vargas Llosa and Carlos Fuentes do not fit so easily within this framework. Arguably, the Boom's culmination was Augusto Roa Bastos's monumental Yo, el supremo (1974). In the wake of the Boom, influential precursors such as Juan Rulfo, Alejo Carpentier, and above all Jorge Luis Borges were also rediscovered. Contemporary literature in the region is vibrant and varied, ranging from the best-selling Paulo Coelho and Isabel Allende to the more avant-garde and critically acclaimed work of writers such as Giannina Braschi, Diamela Eltit, Ricardo Piglia, Roberto Bolaño or Daniel Sada. There has also been considerable attention paid to the genre of testimony, texts produced in collaboration with subaltern subjects such as Rigoberta Menchú. Finally, a new breed of chroniclers is represented by the more journalistic Carlos Monsiváis and Pedro Lemebel. The region boasts six Nobel Prizewinners: in addition to the Colombian García Márquez (1982), also the Chilean poet Gabriela Mistral (1945), the Guatemalan novelist Miguel Ángel Asturias (1967), the Chilean poet Pablo Neruda (1971), the Mexican poet and essayist Octavio Paz (1990), and the Peruvian writer Mario Vargas Llosa (2010). |

文学 主な記事: ラテンアメリカ文学 関連項目: ラテンアメリカ作家一覧 コロンブス以前の文化は主に口承文化であった。ただしアステカやマヤなどは精巧な写本を作成した。神話や宗教的信念に関する口承記録は、ヨーロッパの植民 者が到着した後も時折記録された。ポポル・ヴフがその例である。さらに、口承物語の伝統は今日まで生き残っている。例えばペルーのケチュア語話者やグアテ マラのキチェ族の間でそうである。 ヨーロッパによる大陸の「発見」の瞬間から、初期の探検家や征服者たちは自らの体験を記した文書やクロニカ(年代記)を作成した。コロンブスの書簡やベル ナル・ディアス・デル・カスティーヨによる新スペイン征服の記述などがそれにあたる。植民地時代、文字文化はしばしば教会の手に握られていた。その文脈の 中で、修道女フアナ・イネス・デ・ラ・クルスは記憶に残る詩や哲学的エッセイを執筆した。18世紀末から19世紀初頭にかけて、リサルディの『エル・ペリ キーヨ・サルニエント』(1816年)のような最初の小説を含む、独特のクリオージョ文学伝統が台頭した。 19世紀は批評家ドリス・ゾマーの言う「基礎的虚構」の時代であった。ロマン主義や自然主義の伝統に立つこれらの小説は国民アイデンティティの確立を試 み、しばしば先住民問題や「文明か野蛮か」という二項対立を主題とした(例:ドミンゴ・サルミエント『ファクンド』(1845年)、 フアン・レオン・メラの『クマンダ』(1879年)、エウクリデス・ダ・クーニャの『オズ・セルトン』(1902年)など)。 20世紀の変わり目にモダニズモが現れた。ルベン・ダリオの『アズール』(1888年)を創始的テキストとする詩的運動である。これはラテンアメリカ文学 運動として初めて域外の文学文化に影響を与え、また国民の異なる差異がもはや主要な問題視されなくなった点で、真にラテンアメリカ的な文学の始まりでも あった。例えばホセ・マルティはキューバの愛国者でありながら、メキシコやアメリカ合衆国にも居住し、アルゼンチンなどの雑誌に寄稿した。 しかし、ラテンアメリカ文学を世界的に認知させたのは、間違いなく1960~70年代の文学ブームである。このブームは、大胆で実験的な小説(例えばフリ オ・コルタサールの『レイウエラ』(1963年)など)が頻繁にスペインで出版され、すぐに英語に翻訳されたことで特徴づけられる。このブームを象徴する 小説はガブリエル・ガルシア・マルケスの『百年の孤独』(1967年)であり、これがラテンアメリカ文学とマジックリアリズムの結びつきを生んだ。ただ し、マリオ・バルガス・リョサやカルロス・フエンテスなど同時代の他の重要作家は、この枠組みに容易には収まらない。おそらくブームの頂点はアウグスト・ ロア・バストスの大作『我、至高なる者』(1974年)であった。ブームの後、フアン・ルルフォ、アレホ・カルペンティエル、そして何よりもホルヘ・ルイ ス・ボルヘスといった影響力のある先駆者たちも再発見された。 この地域の現代文学は活気に満ちて多様であり、ベストセラー作家のパウロ・コエーリョやイサベル・アジェンデから、ジャンニーナ・ブラスキ、ディアメラ・ エルティット、リカルド・ピグリア、ロベルト・ボラーニョ、ダニエル・サダといった作家たちのより前衛的で批評家から高く評価される作品まで幅広い。ま た、リゴベルタ・メンチュのようなサバルタンとの共同制作による証言文学というジャンルにも大きな注目が集まっている。最後に、ジャーナリスティックな作 風のカルロス・モンシバイスやペドロ・レメベルに代表される、新たなタイプの記録者たちも登場している。 この地域は6人のノーベル賞受賞者を輩出している。コロンビアのガルシア・マルケス(1982年)に加え、チリの詩人ガブリエラ・ミストラル(1945 年)、 グアテマラの小説家ミゲル・アンヘル・アストゥリアス(1967年)、チリの詩人パブロ・ネルーダ(1971年)、メキシコの詩人・随筆家オクタビオ・パ ス(1990年)、ペルーの作家マリオ・バルガス・リョサ(2010年)が名を連ねている。 |

| Philosophy The history of Latin American philosophy is usefully divided into five periods: Pre-Columbian, Colonial, Independentist, Nationalist, and Contemporary (that is, the twentieth century to the present).[20][21][22] Among the major Latin American philosophers is Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz (Mexico, 1651–1695), a philosopher, composer, poet of the Baroque period, and Hieronymite nun of New Spain (Mexico).[23] Sor Juana was the first philosopher to question the status of the woman in Latin American society.[24] When Catholic Church official instructed Sor Juana to abandon intellectual pursuits that were improper for a woman, Sor Juana's extensive answer defends rational equality between men and women, makes a powerful case for women's right to education, and develops an understanding of wisdom as a form of self-realization.[21] Among the most prominent political philosophers in Latin America was José Martí's (Cuba 1854–1895), who pioneered Cuban liberal thought that lead to the Cuban War of Independence.[25] Elsewhere in Latin America, during the 1870-1930 period, the philosophy of positivism or "cientificismo" associated with Auguste Comte in France and Herbert Spencer in England exerted an influence on intellectuals, experts and writers in the region.[26][27] Francisco Romero (Argentina 1891–1962) coined the phrase 'philosophical normality' in 1940, in reference to philosophical thinking as 'an ordinary function of culture in Hispanic America.' Other Latin American philosophers of his era include Alejandro Korn (Argentina, 1860–1936) who authored 'The Creative Freedom' and José Vasconcelos (Mexico, 1882–1959) whose work spans metaphysics, aesthetics, and the philosophy of 'the Mexican'. Poet and essayist Octavio Paz (1914-1998) was a Mexican diplomat, and poet, and winner of the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1990. Paz who is one of the most influential writers on Latin American and Spanish culture from Sor Juana to Remedios Varos.[28] More recent Latin American philosophers who practice Latina/o or Latino philosophy include: Walter Mignolo (1941-), Maria Lugones (1948-), and Susana Nuccetelli (1954) from Argentina; Jorge J. E. Gracia (1942), Gustavo Pérez Firmat (1949) and Ofelia Schutte (1944) from Cuba;[29] Linda Martín Alcoff (1955) from Panama;[30] Giannina Braschi (1953) from Puerto Rico;[31][32] and Eduardo Mendieta (1963) from Colombia. Their formats and styles of Latino philosophical writing differ greatly as the subject matters. Walter Mignolo's book "The Idea of Latin America" expounds on how the idea of Latin America and Latin American philosopher, as a precursor to Latino philosophy, was formed and propagated. Giannina Braschi's writings on Puerto Rican independence focus on financial terrorism, debt, and “feardom”.[33][34] Latina/o philosophy is a tradition of thought referring both to the work of many Latina/o philosophers in the United States and to a specific set of philosophical problems and method of questioning that relate to Latina/o identity as a hyphenated experience, borders, immigration, gender, race and ethnicity, feminism, and decoloniality.[35] “Latina/o philosophy” is used by some to refer also to Latin American philosophy practiced within Latin America and the United States, while others argue that to maintain specificity Latina/o philosophy should only refer to a subset of Latin American philosophy.[35] |

哲学 ラテンアメリカ哲学の歴史は、五つの時期に区分すると理解しやすい。すなわち、コロンブス以前、植民地時代、独立運動期、ナショナリスト期、そして現代 (つまり20世紀から現在まで)である。[20][21][22] ラテンアメリカの主要な哲学者の一人に、ソア・フアナ・イネス・デ・ラ・クルス(メキシコ、1651–1695)がいる。彼女はバロック時代の哲学者、作 曲家、詩人であり、ヌエバ・エスパーニャ(メキシコ)のヒエロニムス会修道女であった。[23] ソア・フアナは、ラテンアメリカ社会における女性の地位に疑問を投げかけた最初の哲学者である。[24] カトリック教会の役人が、女性にふさわしくない知的追求を放棄するようソル・フアナに指示した際、彼女の長文の返答は男女の理性的平等を擁護し、女性の教 育権を力強く主張し、知恵を自己実現の一形態として理解する見解を展開した。[21] ラテンアメリカで最も著名な政治哲学者の一人に、キューバ独立戦争へとつながるキューバ自由主義思想の先駆者ホセ・マルティ(キューバ、 1854–1895)がいた。[25] ラテンアメリカでは1870年から1930年にかけて、フランスのオーギュスト・コントやイギリスのハーバート・スペンサーに連なる実証主義(サイエン ティフィシズモ)の哲学が、地域の知識人・専門家・作家たちに影響を与えた。[26][27] フランシスコ・ロメロ(アルゼンチン、1891–1962)は1940年、「哲学的正常性」という言葉を造語した。これは哲学的思考を「ヒスパニック・ア メリカにおける文化の通常の機能」と位置付ける概念である。同時代のラテンアメリカ哲学者には、著書『創造的自由』で知られるアレハンドロ・コルン(アル ゼンチン、1860–1936)や、形而上学・美学・「メキシコ人」哲学を扱うホセ・バスコンセロス(メキシコ、1882–1959)がいる。詩人・随筆 家のオクタビオ・パス(1914-1998)はメキシコの外交官であり、詩人であり、1990年にノーベル文学賞を受賞した。パスは、ソル・フアナからレ メディオス・バロスに至るラテンアメリカおよびスペイン文化に関する最も影響力のある作家の一人である。ラティーナ/ラティーノ哲学を実践する近年のラテ ンアメリカ人哲学者には以下が含まれる:アルゼンチン出身のウォルター・ミニョーロ(1941-)、マリア・ルゴネス(1948-)、スサナ・ヌチェテッ リ(1954);キューバ出身のホルヘ・J・E・グラシア(1942)、グスタボ・ペレス・フィルマット(1949)、オフェリア・シュッテ (1944); [29] パナマのリンダ・マルティン・アルコフ(1955年生まれ);[30] プエルトリコのジャンニーナ・ブラスキ(1953年生まれ);[31][32] コロンビアのエドゥアルド・メンディエタ(1963年生まれ)。彼らのラティーノ哲学的著作の形式やスタイルは、主題と同様に大きく異なる。ウォルター・ ミニョーロの著書『ラテンアメリカの理念』は、ラテンアメリカ哲学の先駆けとしての「ラテンアメリカ」という概念とラテンアメリカ人哲学者がいかに形成・ 普及したかを論じている。ジャニーナ・ブラスキのプエルトリコ独立に関する著作は、金融テロリズム、債務、そして「恐怖支配」に焦点を当てている。 [33][34] ラティーナ/オ哲学とは、米国における多数のラティーナ/オ哲学者の業績と、ハイフンで結ばれた経験としてのラティーナ/オのアイデンティティ、国境、移 民、ジェンダー、人種・民族、フェミニズム、脱植民地化といった特定の哲学的問題群および問いかけの方法を指す思想の伝統である。[35] 「ラティーノ哲学」という用語は、ラテンアメリカおよび米国で実践されるラテンアメリカ哲学全体を指す場合もあるが、他方では、特異性を維持するため、ラ ティーノ哲学はラテンアメリカ哲学の一部分のみを指すべきだと主張する者もいる。[35] |

| Music Main article: Music of Latin America Latin American music comes in many varieties, from the simple, rural conjunto music of northern Mexico to the sophisticated habanera of Cuba, from the symphonies of Heitor Villa-Lobos to the simple and moving Andean flute. Music has played an important part in Latin America's turbulent recent history, for example the nueva canción movement. Latin music is very diverse, with the only truly unifying thread being the use of the Spanish language or, in Brazil, the similar Portuguese language.[36] Latin America can be divided into several musical areas. Andean music, for example, includes the countries of western South America, typically Argentina, Colombia, Peru, Bolivia, Ecuador, Chile and Venezuela; Central American music includes Nicaragua, El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras, and Costa Rica. Caribbean music includes the Caribbean coast of Colombia, Panama, and Spanish-speaking islands in the Caribbean, including the Dominican Republic, Cuba, and Puerto Rico.[37] Brazil perhaps constitutes its own musical area, both because of its large size and incredible diversity as well as its unique history as a Portuguese colony. Musically, Latin America has also influenced its former colonial metropoles. Spanish music (and Portuguese music) and Latin American music strongly cross-fertilized each other, but Latin music also absorbed influences from the English-speaking world, as well as African music. One of the main characteristics of Latin American music is its diversity, from the lively rhythms of Central America and the Caribbean to the more austere sounds of southern South America. Another feature of Latin American music is its original blending of the variety of styles that arrived in the Americas and became influential, from the early Spanish and European Baroque to the different beats of the African rhythms. Latino-Caribbean music, such as salsa, merengue, bachata, etc., are styles of music that have been strongly influenced by African rhythms and melodies.[38][39] Other musical genres of Latin America include the Argentine and Uruguayan tango, the Colombian cumbia and vallenato, Mexican ranchera, the Cuban salsa, bolero, rumba and mambo, Nicaraguan palo de mayo, Uruguayan candombe, the Panamanian cumbia, tamborito, saloma and pasillo, and the various styles of music from Pre-Columbian traditions that are widespread in the Andean region. In Brazil, samba, American jazz, European classical music and choro combined into bossa nova.[40] The classical composer Heitor Villa-Lobos (1887–1959) worked on the recording of native musical traditions within his homeland of Brazil. The traditions of his homeland heavily influenced his classical works.[41] Also notable is the much recent work of the Cuban Leo Brouwer and guitar work of the Venezuelan Antonio Lauro and the Paraguayan Agustín Barrios. Arguably, the main contribution to music entered through folklore, where the true soul of the Latin American and Caribbean countries is expressed. Musicians such as Atahualpa Yupanqui, Violeta Parra, Víctor Jara, Mercedes Sosa, Jorge Negrete, Caetano Veloso, Yma Sumac and others gave magnificent examples of the heights that this soul can reach, for example:the Uruguayan born and first Latin American musician to win an OSCAR prize, Jorge Drexler.[42] Latin pop, including many forms of rock, is popular in Latin America today (see Spanish language rock and roll).[43] |

音楽 主な記事: ラテンアメリカの音楽 ラテンアメリカの音楽は多種多様である。メキシコ北部の素朴な田舎のコンジュント音楽から、洗練されたキューバのハバネラまで、エイトール・ヴィラ=ロボ スの交響曲から、シンプルで心に響くアンデスのフルートまで様々だ。音楽はラテンアメリカの激動の近現代史において重要な役割を果たしてきた。例えばヌエ バ・カンシオン運動がそれである。ラテン音楽は非常に多様であり、唯一の真に統一的な要素はスペイン語の使用、あるいはブラジルにおける類似のポルトガル 語の使用である。[36] ラテンアメリカはいくつかの音楽地域に分けられる。例えばアンデス音楽は、南アメリカ西部の国々、典型的にはアルゼンチン、コロンビア、ペルー、ボリビ ア、エクアドル、チリ、ベネズエラを含む。中央アメリカ音楽はニカラグア、エルサルバドル、グアテマラ、ホンジュラス、コスタリカを含む。カリブ音楽は、 コロンビアとパナマのカリブ海沿岸地域、およびドミニカ共和国、キューバ、プエルトリコを含むカリブ海のスペイン語圏諸島を包含する[37]。ブラジル は、その広大な国土と驚異的な多様性、そしてポルトガル植民地としての独自の歴史ゆえに、おそらく独自の音楽圏を構成している。音楽的に、ラテンアメリカ はかつての植民地宗主国にも影響を与えた。スペイン音楽(およびポルトガル音楽)とラテンアメリカ音楽は強く相互に影響し合ったが、ラテン音楽は英語圏や アフリカ音楽からの影響も吸収した。 ラテンアメリカ音楽の主な特徴の一つは、その多様性である。中米やカリブ海の活気あるリズムから、南米南部のより厳格な音色まで多岐にわたる。ラテンアメ リカ音楽のもう一つの特徴は、アメリカ大陸に伝わり影響力を持った様々な様式を独自に融合させた点だ。初期のスペイン・ヨーロッパ・バロックから、異なる アフリカのリズムのビートまでがそれにあたる。 サルサ、メレンゲ、バチャータなどのラテン・カリブ音楽は、アフリカのリズムと旋律に強く影響を受けた音楽様式だ。[38][39] ラテンアメリカのその他の音楽ジャンルには、アルゼンチンとウルグアイのタンゴ、コロンビアのクンビアとバジェナート、メキシコのランチェラ、キューバの サルサ、ボレロ、ルンバ、マンボ、ニカラグアのパロ・デ・マヨ、ウルグアイのカンダンベ、パナマのクンビア、タンボリート、サロマ、パシーヨ、そしてアン デス地域に広く伝わる先コロンブス期の伝統に由来する様々な音楽様式がある。ブラジルでは、サンバ、アメリカのジャズ、ヨーロッパのクラシック音楽、 ショーロが融合してボサノヴァが生まれた。[40] クラシック作曲家エイトール・ヴィラ=ロボス(1887–1959)は、母国ブラジルの土着音楽の伝統を記録する作業に取り組んだ。彼の古典作品には、母 国の伝統が強く影響している[41]。また、キューバのレオ・ブラウエル、ベネズエラのアントニオ・ラウロ、パラグアイのアグスティン・バリオスによる近 年のギター作品も注目に値する。 おそらく、音楽への主な貢献は民俗音楽を通じて行われた。そこにはラテンアメリカとカリブ諸国の真の魂が表現されている。アタワルパ・ユパンキ、ビオレッ タ・パラ、ビクトル・ハラ、メルセデス・ソーサ、ホルヘ・ネグレテ、カエターノ・ヴェローゾ、イマ・スマックといった音楽家たちは、この魂が到達しうる高 みを見事に示した。例えば、ウルグアイ生まれでラテンアメリカ人として初めてアカデミー賞を受賞したホルヘ・ドレクスラーが挙げられる。[42] ラテンポップは、様々な形態のロックを含め、今日のラテンアメリカで人気がある(スペイン語圏のロックンロールを参照)。[43] |

| Film Main article: Latin American cinema  The Cineteca Nacional in Mexico Latin American film is both rich and diverse. But the main centers of production have been Mexico, Argentina, Brazil, and Cuba.  The Guadalajara International Film Festival is considered the most prestigious film festival in Latin America. Latin American cinema flourished after the introduction of sound, which added a linguistic barrier to the export of Hollywood film south of the border. The 1950s and 1960s saw a movement towards Third Cinema, led by the Argentine filmmakers Fernando Solanas and Octavio Getino. More recently, a new style of directing and stories filmed has been tagged as "New Latin American Cinema." Mexican movies from the Golden Era in the 1940s are significant examples of Latin American cinema, with a huge industry comparable to the Hollywood of those years. More recently movies such as Amores Perros (2000) and Y tu mamá también (2001) have been successful in creating universal stories about contemporary subjects, and were internationally recognised. Nonetheless, the country has also witnessed the rise of experimental filmmakers such as Carlos Reygadas and Fernando Eimbicke who focus on more universal themes and characters. Other important Mexican directors are Arturo Ripstein and Guillermo del Toro. Argentine cinema was a big industry in the first half of the 20th century. After a series of military governments that shackled culture in general, the industry re-emerged after the 1976–1983 military dictatorship to produce the Academy Award winner The Official Story in 1985. The Argentine economic crisis affected the production of films in the late 1990s and early 2000s, but many Argentine movies produced during those years were internationally acclaimed, including Plata Quemada (2000), Nueve reinas (2000), El abrazo partido (2004) and Roma (2004). In Brazilian cinema, the Cinema Novo movement created a particular way of making movies with critical and intellectual screenplays, a clearer photography related to the light of the outdoors in a tropical landscape, and a political message. The modern Brazilian film industry has become more profitable inside the country, and some of its productions have received prizes and recognition in Europe and the United States. Movies like Central do Brasil (1999) and Cidade de Deus (2003) have fans around the world, and its directors have taken part in American and European film projects. Cuban cinema has enjoyed much official support since the Cuban revolution, and important filmmakers include Tomás Gutiérrez Alea. |

映画 主な記事: ラテンアメリカ映画  メキシコの国立映画資料館 ラテンアメリカの映画は豊かで多様だ。しかし主な制作拠点はメキシコ、アルゼンチン、ブラジル、キューバであった。  グアダラハラ国際映画祭はラテンアメリカで最も権威ある映画祭と見なされている。 ラテンアメリカ映画は、音声の導入後に発展した。音声はハリウッド映画の南米への輸出に言語的障壁を加えた。1950年代から1960年代にかけて、アル ゼンチンの映画作家フェルナンド・ソラナスとオクタビオ・ゲティーノが主導する「第三の映画」運動が起きた。近年では、新たな演出様式と物語性を備えた作 品群が「新ラテンアメリカ映画」と称されている。 1940年代の黄金期に制作されたメキシコ映画は、当時のハリウッドに匹敵する巨大産業として、ラテンアメリカ映画史における重要な事例だ。近年では『愛 と哀しみの果てに』(2000年)や『君とママも』(2001年)といった作品が現代的な題材で普遍的な物語を創出し、国際的に評価された。一方でカルロ ス・レイガダスやフェルナンド・エイムビケといった実験的な映画作家も台頭し、より普遍的なテーマや人物像に焦点を当てている。その他の重要なメキシコ人 監督にはアルトゥーロ・リプスタインやギレルモ・デル・トロがいる。 アルゼンチン映画は20世紀前半に大きな産業だった。一連の軍事政権が文化全般を束縛した後、1976年から1983年の軍事独裁政権を経て産業は再興 し、1985年にはアカデミー賞受賞作『公式記録』を制作した。1990年代後半から2000年代初頭にかけてのアルゼンチン経済危機は映画製作に影響を 与えたが、この時期に製作された『プラタ・ケマーダ』(2000年)、『ヌエベ・レイナス』(2000年)、『エル・アブラソ・パルティード』(2004 年)、『ローマ』(2004年)など多くのアルゼンチン映画は国際的に高く評価された。 ブラジル映画では、シネマ・ヌーヴォー運動が批判的で知的な脚本、熱帯の風景における自然光を活かした明瞭な撮影技法、政治的メッセージを特徴とする独自 の映画制作手法を生み出した。現代のブラジル映画産業は国内で収益性を高めており、その作品の一部は欧米で賞や評価を得ている。『セントラル・ド・ブラジ ル』(1999年)や『シティ・オブ・ゴッド』(2003年)といった作品は世界中にファンを持ち、その監督たちはアメリカやヨーロッパの映画プロジェク トにも参加している。 キューバ映画は革命以降、政府から多大な支援を受けてきた。トマス・ゲレーロス・アレアは重要な映画製作者の一人である。 |

| Modern dance Main articles: Latin dance and Latin pop Intermediate level international-style Latin dancing at the 2006 MIT ballroom dance competition. A judge stands in the foreground. Latin America has a strong tradition of evolving dance styles. Some of its dance and music is considered to emphasize sexuality, and have become popular outside of their countries of origin. Salsa and the more popular Latin dances were created and embraced into the culture in the early and middle 1900s and have since been able to retain their significance both in and outside the Americas. The mariachi bands of Mexico stirred up quick paced rhythms and playful movements at the same time that Cuba embraced similar musical and dance styles. Traditional dances were blended with new, modern ways of moving, evolving into a blended, more contemporary forms. Ballroom studios teach lessons on many Latin American dances. One can even find the cha-cha being done in honky-tonk country bars. Miami has been a large contributor of the United States' involvement in Latin dancing. With such a huge Puerto Rican and Cuban population one can find Latin dancing and music in the streets at any time of day or night. Some of the dances of Latin America are derived from and named for the type of music they are danced to. For example, mambo, salsa, cha-cha-cha, rumba, merengue, samba, flamenco, bachata, and, probably most recognizable, the tango are among the most popular. Each of the types of music has specific steps that go with the music, the counts, the rhythms, and the style. Modern Latin American dancing is very energetic. These dances primarily are performed with a partner as a social dance, but solo variations exist. The dances emphasize passionate hip movements and the connection between partners. Many of the dances are done in a close embrace while others are more traditional and similar to ballroom dancing, holding a stronger frame between the partners. |

モダンダンス 主な記事:ラテンダンスとラテンポップ 2006年MITボールルームダンス競技会における中級レベルのインターナショナルスタイル・ラテンダンス。手前に審査員が立っている。 ラテンアメリカには、進化を続けるダンススタイルの強い伝統がある。そのダンスや音楽の一部は、性的魅力を強調すると考えられており、原産国以外でも人気 を博している。サルサやより普及したラテンダンスは1900年代前半から中盤にかけて創られ文化に受け入れられ、以来アメリカ大陸内外でその重要性を維持 してきた。メキシコのマリアッチ楽団が速いリズムと遊び心のある動きを生み出す一方で、キューバも同様の音楽・ダンス様式を取り入れた。伝統舞踊は新しい 現代的な動きと融合し、より現代的な形態へと進化した。 社交ダンススタジオでは多くのラテンアメリカ舞踊を教えている。田舎の酒場でもチャチャチャが踊られているのを見かけることがある。マイアミは米国におけ るラテンダンス普及の大きな原動力だ。プエルトリコ人やキューバ人の人口が膨大なため、昼夜を問わず街中でラテンダンスや音楽に出会える。 ラテンアメリカのダンスのいくつかは、踊られる音楽の種類に由来し、その名がついている。例えば、マンボ、サルサ、チャチャチャ、ルンバ、メレンゲ、サン バ、フラメンコ、バチャータ、そしておそらく最も認知度が高いタンゴなどが最も人気のあるダンスだ。それぞれの音楽の種類には、音楽、カウント、リズム、 スタイルに合った特定のステップがある。 現代のラテンアメリカダンスは非常にエネルギッシュだ。これらのダンスは主に社交ダンスとしてパートナーと踊られるが、ソロのバリエーションも存在する。 情熱的な腰の動きとパートナー間の繋がりを重視する。多くのダンスは密着した抱擁で行われる一方、より伝統的で社交ダンスに似たスタイルもあり、パート ナー間でより強いフレームを保つ。 |

| Theatre Theatre in Latin America existed before the Europeans came to the continent. The natives of Latin America had their own rituals, festivals, and ceremonies. They involved dance, singing of poetry, song, theatrical skits, mime, acrobatics, and magic shows. The performers were trained; they wore costumes, masks, makeup, wigs. Platforms had been erected to enhance visibility. The 'sets' were decorated with branches from trees and other natural objects.[44] The Europeans used this to their advantage. For the first fifty years after the Conquest the missionaries used theatre widely to spread the Christian doctrine to a population accustomed to the visual and oral quality of spectacle and thus maintaining a form of cultural hegemony. It was more effective to use the indigenous forms of communication than to put an end to the 'pagan' practices, the conquerors took out the content of the spectacles, retained the trappings, and used them to convey their own message.[45] Pre-Columbian rituals were how the indigenous came in contact with the divine. Spaniards used plays to Christianize and colonize the indigenous peoples of the Americas in the 16th century.[46] Theatre was a potent tool in manipulating a population already accustomed to spectacle. Theatre became a tool for political hold on Latin America by colonialist theatre by using indigenous performance practices to manipulate the population.[47] Theatre provided a way for the indigenous people were forced to participate in the drama of their own defeat. In 1599, the Jesuits even used cadavers of Native Americans to portray the dead in the staging of the final judgment.[48] While the plays were promoting a new sacred order, their first priority was to support the new secular, political order. Theatre under the colonizers primarily at the service of the administration.[45] After the large decrease in the native population, the indigenous consciousness and identity in theatre disappeared, though pieces did have indigenous elements to them.[49] The theatre that progressed in Latin America is argued to be theatre that the conquerors brought to the Americas, not the theatre of the Americas.[50] Progression in Postcolonial Latin American Theatre Internal strife and external interference have been the drive behind Latin American history which applies the same to theatre. 1959–1968: dramaturgical structures and structures of social projects leaned more toward constructing a more native Latin American base called the "Nuestra America". 1968–1974: theatre tries to claim a more homogenous definition which brings in more European models. At this point, Latin American Theatre tried to connect to its historical roots. 1974–1984: the search for expression rooted in the history of Latin America became victims of exile and death.[51] |

劇場 ラテンアメリカの劇場は、ヨーロッパ人が大陸に来る前から存在していた。ラテンアメリカの先住民は独自の儀礼、祭事、典礼を持っていた。そこには舞踊、詩 の詠唱、歌、演劇的な寸劇、パントマイム、曲芸、呪術的ショーが含まれていた。演者は訓練を受けており、衣装、仮面、化粧、かつらを身につけていた。視認 性を高めるために高台が設けられていた。「舞台装置」は木の枝やその他の自然物で装飾されていた。[44] ヨーロッパ人はこれを巧みに利用した。征服後50年間、宣教師たちは演劇を広く活用し、視覚的・口頭的なスペクタクルに慣れた民衆へキリスト教教義を広め た。こうして文化的ヘゲモニーを維持したのである。征服者たちは「異教的」慣習を廃止するより、先住民の伝達手段を用いる方が効果的だと判断した。彼らは スペクタクルの内容を排除しつつ、形式的な装飾は残し、自らのメッセージを伝える手段として利用したのだ。[45] 先コロンブス期の儀礼は、先住民が神聖なものと接触する手段だった。16世紀、スペイン人は演劇を用いてアメリカ大陸の先住民をキリスト教化し植民地化し た。[46] 演劇は、既にスペクタクルに慣れ親しんだ民衆を操る強力な道具となった。植民地主義的演劇は先住民の演技慣行を利用し民衆を操作することで、ラテンアメリ カに対する政治的支配の手段となった。[47] 演劇は先住民が自らの敗北の劇に強制参加する手段となった。1599年にはイエズス会が最終審判の舞台で死者役としてネイティブアメリカンの死体すら利用 した。[48] 演劇が新たな神聖秩序を推進する一方で、その最優先目的は新たな世俗的政治秩序を支えることにあった。植民者支配下の演劇は主に行政の奉仕に徹した。 [45] 先住民人口の大幅な減少後、演劇における先住民の意識とアイデンティティは消滅した。ただし作品には先住民的要素が残存していた。[49] ラテンアメリカで発展した演劇は、アメリカ大陸固有のものではなく、征服者が持ち込んだ演劇であると論じられている。[50] ポストコロニアル期ラテンアメリカ演劇の進展 内紛と外部干渉はラテンアメリカ史の原動力であり、演劇にも同様のことが言える。 1959–1968年:劇作構造と社会プロジェクト構造は、「ヌエストラ・アメリカ」と呼ばれるより土着的なラテンアメリカ基盤の構築に傾いた。 1968–1974年:演劇はより均質な定義を主張しようとし、より多くのヨーロッパ的モデルを取り入れた。この時点で、ラテンアメリカ演劇は自らの歴史 的ルーツとの繋がりを試みた。 1974–1984年:ラテンアメリカの歴史に根ざした表現の探求は、亡命と死の犠牲となった。[51] |

| Latin American cuisine Main article: Latin American cuisine Latin American cuisine refers to the typical foods, beverages, and cooking styles common to many of the countries and cultures in Latin America. Latin America is a very diverse region with cuisines that vary from nation to nation. Some items typical of Latin American cuisine include maize-based dishes and drinks (tortillas, tamales, arepas, pupusas, chicha morada, chicha de jora) and various salsas and other condiments (guacamole, pico de gallo, mole). These spices [specify] are generally what give the Latin American cuisines a distinct flavor; yet, each country of Latin America tends to use a different spice and those that share spices tend to use them at different quantities. Thus, this leads to a variety across the land. Meat is also widely consumed, and constitutes one of the main ingredients in many Latin American countries where they are considered specialties, referred to as Asado or Churrasco. Latin American beverages are just as distinct as their foods. Some of the beverages can even date back to the times of the Native Americans. Some popular beverages include mate, Pisco Sour, horchata, chicha, atole, cacao and aguas frescas. Desserts in Latin America include dulce de leche, alfajor, arroz con leche, tres leches cake, Teja and flan. |

ラテンアメリカ料理 詳細はこちら: ラテンアメリカ料理 ラテンアメリカ料理とは、ラテンアメリカの多くの国や文化に共通する典型的な食品、飲料、調理法を指す。ラテンアメリカは非常に多様性のある地域であり、 国民ごとに料理が異なる。 ラテンアメリカ料理の代表的なものには、トウモロコシを原料とする料理や飲み物(トルティーヤ、タマーレス、アレパス、ププサ、チチャ・モラーダ、チ チャ・デ・ホラ)や、様々なサルサやその他の調味料(ワカモレ、ピコ・デ・ガヨ、モレ)がある。これらのスパイス[特定]が一般的にラテンアメリカ料理に 独特の風味を与えている。しかし、ラテンアメリカの各国は異なるスパイスを使用する傾向があり、同じスパイスを使う場合でも使用量が異なる。そのため、地 域によって多様性が生まれる。肉も広く消費されており、多くのラテンアメリカ諸国では主食材の一つとして、アサードやチュラスコと呼ばれる特産品とされて いる。 ラテンアメリカの飲み物も、その食べ物と同様に特徴的だ。一部の飲み物は先住民の時代まで遡ることもある。代表的な飲み物にはマテ茶、ピスコサワー、オル チャータ、チチャ、アトーレ、カカオ、アグアス・フレスカスなどがある。 ラテンアメリカのデザートには、ドゥルセ・デ・レチェ、アルファホル、アロス・コン・レチェ、トレス・レチェス・ケーキ、テハ、フランなどがある。 |

| Regional

cultures |

地域文化(ご当地/

ご当国文化)→省略 |

| Culture and society in the

Spanish Colonial Americas Culture of South America Hispanic culture Arts by region Sumak Kawsay Amerindians |

スペイン植民地時代のアメリカ大陸における文化と社会 南アメリカの文化 ヒスパニック文化 地域別芸術 スマック・カウサイ アメリカ先住民 |

| References |

|

| Bibliography Alonso, Paul. Satiric TV in the Americas: Critical Metatainment as Negotiated Dissent. Oxford University Press, 2018. Jr., Robert Eli Sanchez (August 26, 2019). Sanchez, Robert Eli (ed.). Latin American and Latinx Philosophy. New York London: Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group. doi:10.4324/9781315100401. ISBN 9781138295865. OCLC 1112422733. Bailey, Gauvin Alexander. Art of colonial Latin America. London: Phaidon, 2005. Bayón, Damián. "Art, c. 1920–c. 1980". In: Leslie Bethell (ed.), A cultural history of Latin America. Cambridge: University of Cambridge, 1998, pp. 393–454. (in Spanish) Belaunde, Víctor Andrés. Peruanidad. Lima: BCR, 1983. Concha, Jaime. "Poetry, c. 1920–1950". In: Leslie Bethell (ed.), A cultural history of Latin America. Cambridge: University of Cambridge, 1998, pp. 227–260. Custer, Tony. The Art of Peruvian Cuisine. Lima: Ediciones Ganesha, 2003. Lucie-Smith, Edward. Latin American art of the 20th century. London: Thames and Hudson, 1993. Martin, Gerald. "Literature, music and the visual arts, c. 1820–1870". In: Leslie Bethell (ed.), A cultural history of Latin America. Cambridge: University of Cambridge, 1998, pp. 3–45. Martin, Gerald. "Narrative since c. 1920". In: Leslie Bethell (ed.), A cultural history of Latin America. Cambridge: University of Cambridge, 1998, pp. 133–225. Olsen, Dale. Music of El Dorado: the ethnomusicology of ancient South American cultures. Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 2002. (in Spanish) Romero, Raúl. "La música tradicional y popular". In: Patronato Popular y Porvenir, La música en el Perú. Lima: Industrial Gráfica, 1985, pp. 215–283. Romero, Raúl. "Andean Peru". In: John Schechter (ed.), Music in Latin American culture: regional tradition. New York: Schirmer Books, 1999, pp. 383–423. Turino, Thomas. "Charango". In: Stanley Sadie (ed.), The New Grove Dictionary of Musical Instruments. New York: MacMillan Press Limited, 1993, vol. I, p. 340. |

参考文献 アロンソ、ポール。『アメリカ大陸の風刺テレビ:交渉された異議申し立てとしての批判的メタテインメント』。オックスフォード大学出版局、2018年。 ジュニア、ロバート・イーライ・サンチェス(2019年8月26日)。サンチェス、ロバート・イーライ(編)。『ラテンアメリカおよびラティーノ哲学』。 ニューヨーク・ロンドン:ラウトリッジ、テイラー&フランシス・グループ。doi:10.4324/9781315100401。ISBN 9781138295865。OCLC 1112422733。 ベイリー、ゴーヴァン・アレクサンダー。『植民地時代のラテンアメリカの芸術』。ロンドン:パイドン、2005年。 バヨン、ダミアン。「芸術、1920年頃~1980年頃」。レスリー・ベセル(編)、『ラテンアメリカの文化史』。ケンブリッジ:ケンブリッジ大学、 1998年、393-454ページ。 (スペイン語) ベラウンデ、ビクトル・アンドレス。『ペルーらしさ』。リマ:BCR、1983年。 コンチャ、ハイメ。「詩、1920年頃~1950年頃」。レスリー・ベセル(編)、『ラテンアメリカの文化史』。ケンブリッジ:ケンブリッジ大学、 1998年、227~260ページ。 カスター、トニー。『ペルー料理の芸術』。リマ:エディシオネス・ガネーシャ、2003年。 ルーシー・スミス、エドワード。『20 世紀のラテンアメリカ美術』。ロンドン:テムズ・アンド・ハドソン、1993 年。 マーティン、ジェラルド。「文学、音楽、視覚芸術、1820 年頃~1870 年頃」。レスリー・ベセル(編)、『ラテンアメリカの文化史』。ケンブリッジ:ケンブリッジ大学、1998 年、3~45 ページ。 マーティン、ジェラルド。「1920 年頃の物語」。レスリー・ベセル(編)、『ラテンアメリカの文化史』。ケンブリッジ:ケンブリッジ大学、1998 年、133-225 ページ。 オルセン、デール。『エルドラドの音楽:古代南米文化の民族音楽学』。ゲインズビル:フロリダ大学出版、2002 年。 (スペイン語)ロメロ、ラウル。「La música tradicional y popular」。パトロナート・ポピュラー・イ・ポルベニール、La música en el Perú。リマ:インダストリアル・グラフィカ、1985年、215-283ページ。 ロメロ、ラウル。「アンデス・ペルー」。ジョン・シェクター(編)、Music in Latin American culture: regional tradition。ニューヨーク:シャーマー・ブックス、1999年、pp. 383–423。 トゥリーノ、トーマス。「チャランゴ」。スタンリー・サディ(編)『ニュー・グローヴ楽器事典』所収。ニューヨーク:マクミラン・プレス・リミテッド、 1993年、第I巻、p. 340。 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Culture_of_Latin_America |

★以下は「ラテンアメリカ研究の虚実」よりインポートしている。オリジナルサイトを参照せよ。

Pan-Latinism in Wikipedia.

"Pan-Latinism first arose in prominence in France particularly from the influence of Michel Chevalier (1806–1879) who contrasted the "Latin" peoples of the Americas with the "Anglo-Saxon" peoples there.[Thomas H. Holloway. A Companion to Latin American History. Blackwell Publishing, Ltd., 2011. P. 7.] 19th century French writer Stendhal spoke of "Latinism" as an imperial idea that the Latins should rule over their non-Latin neighbours.[René Maunier. The Sociology of Colonies: An Introduction to the Study of Race Contact, Part 1. London, England, UK: Routledge, 1949, 1998, 2002. P. 203.] It was later adopted by Napoleon III [1808-1873], who declared support for the cultural unity of Latin peoples and presented France as the modern leader of the Latin peoples to justify French intervention in Mexican politics that led to the creation of the pro-French Second Mexican Empire.[Thomas H. Holloway. op.cit. p.8]"

「汎ラテン主義は、特にミッシェル・シュヴァリエ

(1806年-1879年)の影響により、フランスで最初に注目されるようになった。シュヴァリエは、アメリカ大陸の「ラテン系」の人々と「アングロサク

ソン系」の人々を対比させた。[トーマス・H・ホロウェイ著『ラテンアメリカ史のコンパニオン』Blackwell Publishing,

Ltd.,

2011年、7ページ。19世紀のフランスの作家スタンダールは、「ラテン主義」をラテン人が非ラテン人の隣人を支配すべきだという帝国主義的な考えであ

ると述べた。[René Maunier. The Sociology of Colonies: An Introduction to the

Study of Race Contact, Part 1. London, England, UK: Routledge, 1949,

1998, 2002. 203ページ]

後にナポレオン3世(1808-1873)が採用し、ラテン民族の文化的統一を支持すると宣言し、フランスをラテン民族の近代的指導者として提示し、フラ

ンスによるメキシコ政治への介入を正当化し、親仏派の第二メキシコ帝国の樹立につながった。[トーマス・H・ホロウェイ著『op.cit.』8ページ]」

Modern Latin America

Rousso-Lenoir, Fabienne. America Latina. New York: Assouline, 2002.

書籍紹介:ラテンアメリカの文化の本質は、そのさま ざまな地域や人々を魅力的に描いたこの肖像画に、その輝かしい多様性とともに表現されている。今日、ラテンアメリカは20以上の国々から構成されており、 それぞれが独自の個性的な特別な性質を持っている。パンパスからアマゾン、インカからエル・チェ、グアダルーペの聖母からエビータ、ブエナ・ビスタ・ソシ アル・クラブまで、この洞察力に富んだ本は、歴史を通じてアメリカ・ラティーナの神秘的な魅力に貢献してきた資質やイメージを描き出している。芸術、音 楽、ダンス、文学、映画の世界から引用しつつ、この本は、この魅惑的で興味をそそる文化のミックスの複雑で興味深い性質を探求している。

書籍紹介(別ヴァージョン):それは夢を蒔き、悪夢

で耕された大地である。探検家、征服者、宣教師たちの想像上の地平線を包み込んでいる。現実のラテンアメリカは神話上のラテンアメリカと結びつき、いたる

ところで伝説が問題を曇らせている。文化、宗教、言語、歴史の融合であるラテンアメリカは、魅力的な大陸である。喜びと知識の源であるこの地域について、

歴史的英雄、文化の象徴、文学の偉人たちの引用を交えながら、豊富な図版とともに紹介する。20を超える国々から成り、それぞれが独特で強烈な個性を放つ

ラテンアメリカは、長い間、世界の他の地域に対して不思議な魅力を発揮してきた文化的な豊かさを体現している。この洞察力に富んだ本は、音楽、文学、芸術

を題材に、これらの国の複雑性を掘り下げている。ホルヘ・ルイス・ボルヘスのブエノスアイレスからパブロ・ネルーダの果てしない空間、タンゴやボサノバか

らブエナ・ビスタ・ソシアル・クラブ、グアダルーペの聖母からフリーダ・カーロやエバ・ペロンまで、アメリカ・ラテンアメリカは、この地域の魂の魅力的な

肖像を描き出している。この豪華な本のページをめくるたびに、ラテンアメリカの活気に満ちた精神がほとばしり出てくる。

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Source

from ,

Encyclopedia of Latin American history and culture / Jay Kinsbruner,

editor in chief ; Erick D. Langer, senior editor : set - v. 6. - 2nd

ed. - Detroit : Gale , c2008

1848 1848年革命により王政が終焉、Charles Louis-Napoléon Bonaparte (Napoleon III) 帰国しフランス第二共和政の大統領に就く(-1852)。

1851 国民議会に対するクーデタ、独裁権力を確立

1852 Napoleon III、皇帝に即 位。第二帝政がはじまる

1853-1856 クリミア戦争による、ウィーン体制の崩壊。

1861 ベニート・ファレス大統領、西欧列強(英仏西)に対して対外債務モラトリアム宣

言。10月31日3国はロンドン条約締結、支払いのために派兵を決定。

1862 フランスの 介入開始

1863 6月メキシコ市陥落。オーストリア皇弟フェルディナント・ヨーゼフ・マクシミリア ン大公(Ferdinand Maximilian Joseph Maria von Habsburg-Lothringen)を皇帝を宣言。

1865 メキシコ共和国軍の巻き返しはじまる。

1867 6月マキシ

ミリアン処刑、共和国軍の勝利

1870 フランス第三共和政(-1940)

1871 ファレス再選するも、再選禁止によりポリフィリオ・ディアスの反乱。ファレスは、 翌年に急死。セバスティアン・レルド・デ・タヒーア暫定大統領。

1876 ディアスはクーデターにより大統領就任(-1911)

1966 Founding of the "Latin American Studies Association,

LASA".

サイト内リンク集

リンク

文献

その他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆