Dialogue

対話

Dialogue

解説:池田光穂

対話論理とは、対話状況が生み出すコミュニケーションの際 に、複数の主体に共有される理性あるいは共通感覚のこと。

対話は通常複数の人たちのあいだで生起す るものである。また対話が続く状況とは、共通の理解や価値観が重なりあいながらも、けっして同一のもの にならないことである(合致すれば対話が終わるからである)。

対話が内包するこのような複数の理性や感 覚を、対話論理(dia-logic, dialogic reason)と呼んでもいいだろう。

カテリーナ・クラークとマイケル・ホルク

イスト(1990)によると、ミハイル・バフチンの思想は「対話主義

(dialogism)」と呼ばれる。

■ 対話論テー ゼ(Dialogic Thesis, 2009)

★対話というものはなく,対話は欺瞞です

(ジャック・ラカン ca.1968)——[ルディネスコ 2001:364]

★対話論理にまつわる私のエッセーは「対話論理」 でお読みください。

| Dialogue (sometimes

spelled dialog in American English)[1] is a written or spoken

conversational exchange between two or more people, and a literary and

theatrical form that depicts such an exchange. As a philosophical or

didactic device, it is chiefly associated in the West with the Socratic

dialogue as developed by Plato, but antecedents are also found in other

traditions including Indian literature.[2] Etymology  Frontispiece and title page of Galileo's Dialogue Concerning the Two Chief World Systems, 1632  John Kerry listens to a Question of reporter Matt Lee, after giving remarks on World Press Freedom Day (3rd May 2016). The term dialogue stems from the Greek διάλογος (dialogos, conversation); its roots are διά (dia: through) and λόγος (logos: speech, reason). The first extant author who uses the term is Plato, in whose works it is closely associated with the art of dialectic.[3] Latin took over the word as dialogus.[4] |

対話(アメリカ英語ではdialogと表記されることもある)[1]と

は、2人以上の人物による書面または口頭での会話のやり取り、およびそのようなやり取りを描いた文学や演劇の形式である。哲学や教訓的な手法として、西洋

では主にプラトンが発展させたソクラテス的対話と関連付けられているが、インド文学を含む他の伝統にも先例が見られる。 語源  ガリレオ著『二つの主要な世界体系に関する対話』の口絵とタイトルページ、1632年  世界報道の自由デー(2016年5月3日)でスピーチを行った後、ジョン・ケリーは記者マット・リーの質問に耳を傾けた。 「対話」という用語は、ギリシャ語の「διάλογος(dialogos、会話)」に由来する。その語源は、「διά(dia:通して)」と 「λόγος(logos:スピーチ、理由)」である。この用語を初めて使用した現存する作家はプラトンであり、彼の作品では弁証法と密接に関連してい る。[3] ラテン語では「dialogus」という言葉が使われるようになった。[4] |

As genre Oldest extant text of Plato's Republic Antiquity Dialogue as a genre in the Middle East and Asia dates back to ancient works, such as Sumerian disputations preserved in copies from the late third millennium BC,[5] Rigvedic dialogue hymns, and the Mahabharata. In the West, Plato (c. 427 BC – c. 348 BC) has commonly been credited with the systematic use of dialogue as an independent literary form.[6] Ancient sources indicate, however, that the Platonic dialogue had its foundations in the mime, which the Sicilian poets Sophron and Epicharmus had cultivated half a century earlier.[7] These works, admired and imitated by Plato, have not survived and we have only the vaguest idea of how they may have been performed.[8] The Mimes of Herodas, which were found in a papyrus in 1891, give some idea of their character.[9] Plato further simplified the form and reduced it to pure argumentative conversation, while leaving intact the amusing element of character-drawing.[10] By about 400 BC he had perfected the Socratic dialogue.[11] All his extant writings, except the Apology and Epistles, use this form.[12] Following Plato, the dialogue became a major literary genre in antiquity, and several important works both in Latin and in Greek were written. Soon after Plato, Xenophon wrote his own Symposium; also, Aristotle is said to have written several philosophical dialogues in Plato's style (of which only fragments survive).[13] In the 2nd century CE, Christian apologist Justin Martyr wrote the Dialogue with Trypho, which was a discourse between Justin representing Christianity and Trypho representing Judaism. Another Christian apologetic dialogue from the time was the Octavius, between the Christian Octavius and pagan Caecilius. Japan In the East, in 13th century Japan, dialogue was used in important philosophical works. In the 1200s, Nichiren Daishonin wrote some of his important writings in dialogue form, describing a meeting between two characters in order to present his argument and theory, such as in "Conversation between a Sage and an Unenlightened Man" (The Writings of Nichiren Daishonin 1: pp. 99–140, dated around 1256), and "On Establishing the Correct Teaching for the Peace of the Land" (Ibid., pp. 6–30; dated 1260), while in other writings he used a question and answer format, without the narrative scenario, such as in "Questions and Answers about Embracing the Lotus Sutra" (Ibid., pp. 55–67, possibly from 1263). The sage or person answering the questions was understood as the author. Modern period Two French writers of eminence borrowed the title of Lucian's most famous collection; both Fontenelle (1683) and Fénelon (1712) prepared Dialogues des morts ("Dialogues of the Dead").[6] Contemporaneously, in 1688, the French philosopher Nicolas Malebranche published his Dialogues on Metaphysics and Religion, thus contributing to the genre's revival in philosophic circles. In English non-dramatic literature the dialogue did not see extensive use until Berkeley employed it, in 1713, for his treatise, Three Dialogues between Hylas and Philonous.[10] His contemporary, the Scottish philosopher David Hume wrote Dialogues Concerning Natural Religion. A prominent 19th-century example of literary dialogue was Landor's Imaginary Conversations (1821–1828).[14] In Germany, Wieland adopted this form for several important satirical works published between 1780 and 1799. In Spanish literature, the Dialogues of Valdés (1528) and those on Painting (1633) by Vincenzo Carducci are celebrated. Italian writers of collections of dialogues, following Plato's example, include Torquato Tasso (1586), Galileo (1632), Galiani (1770), Leopardi (1825), and a host of others.[10] In the 19th century, the French returned to the original application of dialogue. The inventions of "Gyp", of Henri Lavedan, and of others, which tell a mundane anecdote wittily and maliciously in conversation, would probably present a close analogy to the lost mimes of the early Sicilian poets. English writers including Anstey Guthrie also adopted the form, but these dialogues seem to have found less of a popular following among the English than their counterparts written by French authors.[10] The Platonic dialogue, as a distinct genre which features Socrates as a speaker and one or more interlocutors discussing some philosophical question, experienced something of a rebirth in the 20th century. Authors who have recently employed it include George Santayana, in his eminent Dialogues in Limbo (1926, 2nd ed. 1948; this work also includes such historical figures as Alcibiades, Aristippus, Avicenna, Democritus, and Dionysius the Younger as speakers). Also Edith Stein and Iris Murdoch used the dialogue form. Stein imagined a dialogue between Edmund Husserl (phenomenologist) and Thomas Aquinas (metaphysical realist). Murdoch included not only Socrates and Alcibiades as interlocutors in her work Acastos: Two Platonic Dialogues (1986), but featured a young Plato himself as well.[15] More recently Timothy Williamson wrote Tetralogue, a philosophical exchange on a train between four people with radically different epistemological views. In the 20th century, philosophical treatments of dialogue emerged from thinkers including Mikhail Bakhtin, Paulo Freire, Martin Buber, and David Bohm. Although diverging in many details, these thinkers have proposed a holistic concept of dialogue.[16] Educators such as Freire and Ramón Flecha have also developed a body of theory and techniques for using egalitarian dialogue as a pedagogical tool.[17] |

ジャンルとしての 現存する最古のプラトン著『国家』のテキスト 古代 中東およびアジアにおける対話というジャンルは、紀元前3千年紀後半の写本に保存されているシュメールの論争[5]、リグヴェーダの対話形式の賛歌、マ ハーバーラタなどの古代の作品にまで遡る。 西洋では、プラトン(紀元前427年頃 - 紀元前348年頃)が対話形式を独立した文学形式として体系的に用いたことで広く知られている。[6] しかし古代の資料によると、プラトンの対話は、シチリアの詩人ソフロンとエピクラーメスが半世紀前に開拓したマイムを基礎としていることが示されている。 半世紀前にシチリアの詩人ソフロンとエピクラーモスが培っていた。[7] プラトンが賞賛し模倣したこれらの作品は現存しておらず、どのように上演されていたのかについては、漠然とした考えしか持っていない。[8] 1891年にパピルスで発見されたヘロダスの『ミメー』は、その性格についていくつかの考えを与えている。[9] プラトンはさらに形式を簡素化し、純粋な論争の会話にまで縮小したが、人物描写の面白さはそのまま残した。[10] 紀元前400年頃には、ソクラテス対話を完成させた。[11] 現存するプラトンの著作のうち、『弁明』と『書簡』を除くすべての作品がこの形式を用いている。[12] プラトンに続いて、対話は古代の主要な文学ジャンルとなり、ラテン語とギリシャ語でいくつかの重要な作品が書かれた。プラトンに続いて、クセノフォンは自 身の『饗宴』を著した。また、アリストテレスはプラトンのスタイルでいくつかの哲学対話を書いたと言われている(現存するのは断片のみ)。2世紀には、キ リスト教の擁護者であるユスティノス殉教者が『トリフォとの対話』を著した。これは、キリスト教を代表するユスティノスとユダヤ教を代表するトリフォとの 対話である。同時代のキリスト教弁証論の対話としては、キリスト教徒オクタヴィウスと異教徒ケシリオスの対話『オクタヴィウス』がある。 日本 東洋では、13世紀の日本において、対話形式が重要な哲学作品で用いられた。1200年代には、日蓮大聖人がいくつかの重要な著作を対話形式で書き、2人 の登場人物の会話を描写することで、自身の主張や理論を提示した。例えば、『聖人と未信者との問答』(『日蓮大聖人書簡集』1: pp. 99–140、1256年頃)や )や「正しい教えを定立して国家を安穏にすることについて」(同書、6~30ページ、1260年)など、2人の登場人物の対話を描写することで、自らの主 張や理論を提示した。一方、「法華経を信奉することに関する問答」(同書、55~67ページ、1263年頃)など、物語のシナリオを排除した質疑応答形式 の著作もある。賢者や質問に答える人物が著者のように理解されていた。 近代 著名なフランスの作家2人がルシアンの最も有名な作品集のタイトルを借用した。フォンテネル(1683年)とフェヌロン(1712年)は、ともに『死者の 対話』(Dialogues of the Dead)を著した。[6] 同時代の1688年には、フランスの哲学者ニコラ・マレブランシュが『形而上学と宗教についての対話』を出版し、哲学界におけるこのジャンルの復活に貢献 した。英語の非劇文学では、バークレーが1713年に著書『ヒュラスとフィロンヌスの間の3つの対話』で用いるまで、対話はあまり用いられなかった。 [10] 彼の同時代人であるスコットランドの哲学者デイヴィッド・ヒュームは『自然宗教に関する対話』を著した。19世紀の著名な文学作品の対話の例としては、ラ ンドーの『想像上の対話』(1821年~1828年)がある。[14] ドイツでは、ヴィーラントが1780年から1799年の間に発表したいくつかの重要な風刺作品でこの形式を採用した。スペイン文学では、ビセンテ・カル ドゥッチの『バルデス対話集』(1528年)や『絵画論』(1633年)が有名である。イタリアの作家たちも、プラトンの例にならって対話集を書いた。ト ルクァート・タッソ(1586年)、ガリレオ(1632年)、ガリアーニ(1770年)、レオパルディ(1825年)など、その他多数の作家が挙げられ る。 19世紀には、フランス人が対話の本来の用途に戻った。アンリ・ラヴァダンの「ジップ」やその他の作品に見られる、会話の中で平凡な逸話を機知に富んで悪 意を持って語るという手法は、おそらくは失われた初期シチリア詩人のパントマイムに近い類似性があるだろう。アンスティ・ガスリーを含む英国の作家たちも この形式を採用したが、フランス人作家によるものに比べると、英国ではこの種の対話形式はあまり人気がなかったようである。 プラトンの対話形式は、ソクラテスを話し手とし、1人または複数の対話者が哲学的問題について議論するという独特のジャンルであり、20世紀に復活を遂げ た。最近この形式を用いた作家としては、ジョージ・サンタヤーナが挙げられる。彼の著名な著書『リンボーの対話』(1926年、第2版1948年)では、 アルキビアデス、アリストパネス、アヴィセンナ、デモクリトス、ディオニュシオス・ヤングなどの歴史上の人物も登場人物として登場する。また、エディス・ スタインやアイリス・マードックも対話形式を用いた。シュタインは、現象学者のエドムント・フッサールと形而上学的実在論者のトマス・アクィナスとの対話 を想像した。マードックは、作品『Acastos: Two Platonic Dialogues』(1986年)で、ソクラテスとアルキビアデスを対話者として登場させただけでなく、若きプラトン自身も登場させた。[15] さらに最近では、ティモシー・ウィリアムソンが著書『Tetralogue』で、根本的に異なる認識論的見解を持つ4人の人物による列車内での哲学的な意 見交換を描いている。 20世紀には、ミハイル・バフチン、パウロ・フレイレ、マーティン・ブーバー、デヴィッド・ボームなどの思想家たちによって、哲学的な対話の扱い方が登場 した。 これらの思想家たちは、多くの点で異なっているものの、対話の全体論的な概念を提唱している。[16] フレイレやラモン・フレチャなどの教育者も、平等主義的な対話を教育の道具として使用するための理論と技術体系を開発している。[17] |

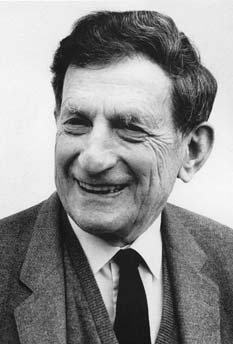

| As topic Main article: Philosophy of dialogue  David Bohm, a leading 20th-century thinker on dialogue Martin Buber assigns dialogue a pivotal position in his theology. His most influential work is titled I and Thou.[18] Buber cherishes and promotes dialogue not as some purposive attempt to reach conclusions or express mere points of view, but as the very prerequisite of authentic relationship between man and man, and between man and God. Buber's thought centres on "true dialogue", which is characterised by openness, honesty, and mutual commitment.[19] The Second Vatican Council placed a major emphasis on dialogue with the World. Most of the council's documents involve some kind of dialogue : dialogue with other religions (Nostra aetate), dialogue with other Christians (Unitatis Redintegratio), dialogue with modern society (Gaudium et spes) and dialogue with political authorities (Dignitatis Humanae).[20] However, in the English translations of these texts, "dialogue" was used to translate two Latin words with distinct meanings, colloquium ("discussion") and dialogus ("dialogue").[21] The choice of terminology appears to have been strongly influenced by Buber's thought.[22] The physicist David Bohm originated a related form of dialogue where a group of people talk together in order to explore their assumptions of thinking, meaning, communication, and social effects. This group consists of ten to thirty people who meet for a few hours regularly or a few continuous days. In a Bohm dialogue, dialoguers agree to leave behind debate tactics that attempt to convince and, instead, talk from their own experience on subjects that are improvised on the spot.[23] In his influential works, Russian philosopher Mikhail Bakhtin provided an extralinguistic methodology for analysing the nature and meaning of dialogue:[24] Dialogic relations have a specific nature: they can be reduced neither to the purely logical (even if dialectical) nor to the purely linguistic (compositional-syntactic) They are possible only between complete utterances of various speaking subjects... Where there is no word and no language, there can be no dialogic relations; they cannot exist among objects or logical quantities (concepts, judgments, and so forth). Dialogic relations presuppose a language, but they do not reside within the system of language. They are impossible among elements of a language.[25] The Brazilian educationalist Paulo Freire, known for developing popular education, advanced dialogue as a type of pedagogy. Freire held that dialogued communication allowed students and teachers to learn from one another in an environment characterised by respect and equality. A great advocate for oppressed peoples, Freire was concerned with praxis—action that is informed and linked to people's values. Dialogued pedagogy was not only about deepening understanding; it was also about making positive changes in the world: to make it better.[26] |

トピックとして 詳細は「対話の哲学」を参照  20世紀を代表する対話論者、デヴィッド・ボーム マルティン・ブーバーは、神学において対話を極めて重要な位置づけとしている。彼の最も影響力のある著作は『我と汝』というタイトルである。[18] ブーバーは、対話を単に結論に達したり、単なる意見を表明するための目的を持った試みとしてではなく、人間と人間、人間と神との間の真の関係の前提条件と して大切にし、推進している。ブーバーの思想は「真の対話」に集約され、それは開放性、誠実さ、相互のコミットメントによって特徴づけられる。[19] 第2バチカン公会議は、世界との対話に大きな重点を置いた。公会議の文書のほとんどは、何らかの対話に関係している。すなわち、他の宗教との対話(『われ らの時代』)、他のキリスト教徒との対話(『教会の一致』)、現代社会との対話(『喜びと希望』)、政治当局との対話(『人間の尊厳』)などである。[2 しかし、これらの文章の英語訳では、「対話」という語は、意味の異なる2つのラテン語、colloquium(「議論」)とdialogus(「対話」) に訳されている。[21] 用語の選択は、ブーバーの思想に強く影響されているように見える。[22] 物理学者のデビッド・ボームは、思考、意味、コミュニケーション、社会的影響に関する前提を探求するために、人々が集まって話し合うという、関連した対話 の形式を考案した。このグループは10人から30人で構成され、定期的に数時間、または数日間にわたって会合を開く。ボームの対話では、参加者は説得しよ うとする議論の戦術を捨て、その場で即興で選んだテーマについて、各自の経験に基づいて話すことに同意する。 ロシアの哲学者ミハイル・バフチンは、影響力のある著作の中で、対話の本質と意味を分析するための言語外の方法論を提示している。[24] 対話関係には固有の性質がある。それは、純粋に論理的なもの(弁証法的であっても)にも、純粋に言語的なもの(構成的・統語的なもの)にも還元できない。 対話関係は、さまざまな話し手による完全な発話の間でのみ可能である。言葉も言語もないところでは、対話関係はありえない。対話関係は言語を前提とする が、言語のシステム内に存在するわけではない。言語の要素の間では対話関係は不可能である。[25] 大衆教育の開発で知られるブラジルの教育学者パウロ・フレイレは、対話を教育の一形態として推進した。フレイレは、対話型のコミュニケーションによって、 生徒と教師が互いに尊敬と平等を尊重する環境で学び合うことができると主張した。抑圧された人々を擁護する立場に立つフレイレは、実践、すなわち人々の価 値観に根ざし、それらと結びついた行動に重点を置いていた。対話型教育は、理解を深めるだけでなく、世界をより良いものに変えるという積極的な変化をもた らすものでもある。[26] |

| As practice Main article: Dialogic learning  A conversation amongst participants in a 1972 cross-cultural youth convention Dialogue is used as a practice in a variety of settings, from education to business. Influential theorists of dialogal education include Paulo Freire and Ramon Flecha. In the United States, an early form of dialogic learning emerged in the Great Books movement of the early to mid-20th century, which emphasised egalitarian dialogues in small classes as a way of understanding the foundational texts of the Western canon.[27] Institutions that continue to follow a version of this model include the Great Books Foundation, Shimer College in Chicago,[28] and St. John's College in Annapolis and Santa Fe.[29] Egalitarian dialogue Main article: Egalitarian dialogue Egalitarian dialogue is a concept in dialogic learning. It may be defined as a dialogue in which contributions are considered according to the validity of their reasoning, instead of according to the status or position of power of those who make them.[30] Structured dialogue Structured dialogue represents a class of dialogue practices developed as a means of orienting the dialogic discourse toward problem understanding and consensual action. Whereas most traditional dialogue practices are unstructured or semi-structured, such conversational modes have been observed as insufficient for the coordination of multiple perspectives in a problem area. A disciplined form of dialogue, where participants agree to follow a dialogue framework or a facilitator, enables groups to address complex shared problems.[31] Aleco Christakis (who created structured dialogue design) and John N. Warfield (who created science of generic design) were two of the leading developers of this school of dialogue.[32] The rationale for engaging structured dialogue follows the observation that a rigorous bottom-up democratic form of dialogue must be structured to ensure that a sufficient variety of stakeholders represents the problem system of concern, and that their voices and contributions are equally balanced in the dialogic process. Structured dialogue is employed for complex problems including peacemaking (e.g., Civil Society Dialogue project in Cyprus) and indigenous community development.,[33] as well as government and social policy formulation.[34] In one deployment, structured dialogue is (according to a European Union definition) "a means of mutual communication between governments and administrations including EU institutions and young people. The aim is to get young people's contribution towards the formulation of policies relevant to young peoples lives."[35] The application of structured dialogue requires one to differentiate the meanings of discussion and deliberation. Groups such as Worldwide Marriage Encounter and Retrouvaille use dialogue as a communication tool for married couples. Both groups teach a dialogue method that helps couples learn more about each other in non-threatening postures, which helps to foster growth in the married relationship.[36] Dialogical leadership The German philosopher and classicist Karl-Martin Dietz emphasises the original meaning of dialogue (from Greek dia-logos, i.e. 'two words'), which goes back to Heraclitus: "The logos [...] answers to the question of the world as a whole and how everything in it is connected. Logos is the one principle at work, that gives order to the manifold in the world."[37] For Dietz, dialogue means "a kind of thinking, acting and speaking, which the logos "passes through""[38] Therefore, talking to each other is merely one part of "dialogue". Acting dialogically means directing someone's attention to another one and to reality at the same time.[39] Against this background and together with Thomas Kracht, Karl-Martin Dietz developed what he termed "dialogical leadership" as a form of organisational management.[40] In several German enterprises and organisations it replaced the traditional human resource management, e.g. in the German drugstore chain dm-drogerie markt.[40] Separately, and earlier to Thomas Kracht and Karl-Martin Dietz, Rens van Loon published multiple works on the concept of dialogical leadership, starting with a chapter in the 2003 book The Organization as Story.[41] Moral dialogues Moral dialogues are social processes which allow societies or communities to form new shared moral understandings. Moral dialogues have the capacity to modify the moral positions of a sufficient number of people to generate widespread approval for actions and policies that previously had little support or were considered morally inappropriate by many. Communitarian philosopher Amitai Etzioni has developed an analytical framework which—modelling historical examples—outlines the reoccurring components of moral dialogues. Elements of moral dialogues include: establishing a moral baseline; sociological dialogue starters which initiate the process of developing new shared moral understandings; the linking of multiple groups' discussions in the form of "megalogues"; distinguishing the distinct attributes of the moral dialogue (apart from rational deliberations or culture wars); dramatisation to call widespread attention to the issue at hand; and, closure through the establishment of a new shared moral understanding.[42] Moral dialogues allow people of a given community to determine what is morally acceptable to a majority of people within the community. |

実践として 詳細は「対話的学習」を参照  1972年の異文化交流青少年大会の参加者たちの会話 対話は、教育からビジネスまで、さまざまな場面で実践として用いられている。対話的教育の有力な理論家には、パウロ・フレイレやラモン・フレチャなどがい る。 米国では、対話型学習の初期の形態は20世紀前半から半ばにかけてのグレート・ブックス運動において現れた。この運動では、西洋の正典の基礎的なテキスト を理解する方法として、少人数制の平等な対話を重視していた。[27] このモデルのバージョンを現在も採用している機関には、グレート・ブックス財団、シカゴのシマー大学[28]、アナポリスとサンタフェのセント・ジョンズ 大学がある。[29] 平等主義的対話 詳細は「平等主義的対話」を参照 平等主義的対話は、対話型学習における概念である。平等主義的対話とは、発言者の地位や権力ではなく、その論拠の妥当性に基づいて発言が検討される対話と 定義できる。 構造化された対話 構造化された対話は、問題の理解と合意に基づく行動に向けた対話的談話の方向づけの手段として開発された対話実践の一種である。従来の対話実践のほとんど は、非構造化または半構造化されているが、このような会話様式は、問題領域における複数の視点の調整には不十分であることが観察されている。参加者が対話 の枠組みや進行役に従うことに同意する訓練された対話の形式は、グループが複雑な共有問題に対処することを可能にする。 アレコ・クリスタキス(構造化対話の設計者)とジョン・N・ウォーフィールド(ジェネリックデザインの科学者)は、この対話学派の主要な開発者の2人であ る。[32] 構造化対話を採用する根拠は、ボトムアップの厳格な民主的対話形式を構造化し、関心のある問題システムを十分に多様な利害関係者が代表し、対話プロセスに おいて彼らの声や貢献が平等に反映されるようにしなければならないという観察に基づいている。 構造化された対話は、平和構築(例えば、キプロスにおける市民社会対話プロジェクト)や先住民コミュニティ開発などの複雑な問題、[33] および政府や社会政策の策定[34] に用いられている。 その一例として、構造化された対話は(欧州連合の定義によると)「EU機関や若者を含む政府および行政機関間の相互コミュニケーションの手段」である。そ の目的は、若者たちの生活に関連する政策の策定に若者たちの貢献を得ることである。[35] 構造化された対話の適用には、議論と審議の意味を区別することが必要である。 ワールドワイド・マリッジ・エンカウンターやレトロヴェールなどの団体は、夫婦間のコミュニケーションツールとして対話を活用している。両団体とも、夫婦 がお互いを脅威に感じることなく、より深く理解し合える対話法を指導しており、夫婦関係の成長を促すのに役立つ。 対話型リーダーシップ ドイツの哲学者で古典学者のカール・マルティン・ディーツは、ヘラクレイトスにまで遡る対話の本来の意味(ギリシャ語の「dia-logos」、すなわち 「2つの言葉」)を強調している。「ロゴスは、世界全体に対する質問に答え、その世界におけるすべてのものがどのように結びついているかを明らかにする。 ロゴスは、世界における多様性に秩序を与える、作用する唯一の原理である」[37] ディーツにとって、対話とは「ロゴスが『通過する』思考、行動、発言の一種」[38] を意味する。したがって、お互いに話し合うことは「対話」のほんの一部にすぎない。対話的に行動するということは、他者と現実の両方に同時に注意を向ける ことを意味する。[39] こうした背景を踏まえ、カール=マルティン・ディーツはトーマス・クラハトとともに、組織運営の形として「対話型リーダーシップ」を提唱した。[40] ドイツのいくつかの企業や組織では、従来の人的資源管理に代わるものとして、例えばドイツのドラッグストア・チェーンであるdm-drogerie marktで採用されている。[40] また、トーマス・クラハトやカール=マルティン・ディーツに先んじて、レンス・ファン・ルーンが2003年の著書『The Organization as Story』の章を皮切りに、対話型リーダーシップの概念に関する複数の著作を発表している。 道徳的対話 道徳的対話とは、社会やコミュニティが新たな共通の道徳的認識を形成することを可能にする社会的プロセスである。道徳的対話は、以前にはほとんど支持され ていなかったり、多くの人々から道徳的に不適切であると考えられていた行動や政策に対して、十分な数の人々の道徳的立場を修正し、広範な支持を生み出す能 力がある。コミュニタリアン(共同体主義者)の哲学者アミタイ・エッツィオーニは、歴史的な事例をモデルとして、道徳的対話に繰り返し見られる要素を概説 する分析的枠組みを開発した。道徳的対話の要素には、道徳的基準値の設定、新しい共通の道徳的理解を育むプロセスを開始する社会学的な対話のきっかけ、複 数のグループの議論を「メガログ」という形式でつなげること、道徳的対話の明確な属性を区別すること(理性的な審議や文化戦争とは区別して)、 、問題への幅広い関心を喚起するためのドラマ化、そして、新たな共有道徳的理解の確立による終結などである。[42] 道徳的対話は、特定のコミュニティの人々が、そのコミュニティ内の大多数の人々にとって何が道徳的に受け入れられるかを決定することを可能にする。 |

| Argumentation theory Collaborative leadership Deliberation Dialogical self Dialogue Among Civilizations Dialogue (Bakhtin) Dialogue mapping Intercultural dialogue Interfaith dialogue Intergroup dialogue Rogerian argument Speech |

議論理論 協調的リーダーシップ 熟慮 対話的自己 文明間の対話 対話(バフチン) 対話マッピング 異文化間対話 宗教間対話 集団間対話 ロジャーズ的議論 スピーチ |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dialogue |

■ リンク

■ 文献

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

Copyleft,

CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099