ポポル・ヴフ

Popol Vuj

ポポル・ヴフ

Popol Vuj

ポポル・ヴフ神話(Popol Vuj):『ポポル・ブフ』とはグアテマラ先住民キチェの人たちがスペイン征服期以前から伝承していた世界の創世神話である。双子の英雄フンアフプーとイ シュバランケーらが織りなす冒険譚、世界の来歴、混沌と秩序、人間がトウモロコシからうまれるなど、読者をわくわく、ハラハラさせる。今日でもさまざまな 校本と翻訳がある。18世紀にドミニコ会司祭のフランシスコ・シメーネス[ヒメネス](1666-c.1729)が採集し保管していたが、19世紀に偶然に発見、翻訳 されて、西洋世界にもたらされた。デニス・テッドロックは、それを現代キチェ語とスペイン語に対訳翻訳し、現地の伝統文化の復興に文化人類学者として大い に貢献した(この項目は第2章脚注(1)の再掲である)(→『ポポル・ヴフ』機能的索引)。

なお「20世紀になって、何人かの学者がヒメネスの

翻訳を検討した結果、ヒメネスは定量化できないほどの不正確な訳を導入しており、さらにヒメネスのポポル・ブ

フの翻訳を詳細に検討することが不可能なことから、その翻訳は非常に不誠実で、修道士が高い割合で訳を省略していると結論づけた。この発見は、ポポル・ブ

フの最初の1180行を、修道士が作成した2つのスペイン語版と徹底的に比較分析した結果である。また、『ポポル・ブフ』が西洋的な発想で書かれた書物で

あることは、その構成の統一性から、物語の収集者が一人であるとする根拠があることも指摘されている。批評家は、ヒメネスがどの程度テキストと相互作用し

たかは十分に確立されておらず、最初のフォリオ・レクトに含まれるアイデアのいくつかは、完全に土着のものではないと確認できると結論づけた」二人のヒメネス」より)

第1部から第4部までの4部構成である。第1部の第 1章、第2章、第3章→第2部と第4部:宇宙と人類の形成、キチェ4人(柱)の創造とその子孫の、移動、征服、供犠、祭祀、天体の移動、が描かれる。そし て、第1部の第4章〜第9章:双子のフンアフプーとイシュバランケーが、巨人ヴクブ・カキシュとその子どもシバクナーとカブラカンを退治する物語(夜の出 来事)がメインである。さらに、第2部(全14章):第1部第9章を受けて、双子の誕生について話す。双子の父親のフン・フンアフプーとオジのヴクブ・フ ンアフプーの兄弟が、シバルバーの神に破れて、木に吊るされたフン・フンアフプーの首がヒカロの実になり唾で少女を孕ませたことなど。双子のフンアフプー とイシュバランケーは、異母兄のフンバッツとフンチョウエンを猿に変身させ、シバルバーの神を滅ぼし父の仇を報い、最後に太陽と月になり天に昇る。

| 部 |

頁 |

【略号】フナ→フナアフプー(フンアプ

フー);イシュ→イシュバランケーの2人は双子の文化的英雄 |

アドリアン・レシーノス原訳校注 ;

ディエゴ・リベラ挿絵 ; 林屋永吉訳『ポポル・ヴフ』1972年 |

| 1 |

59 |

序文 |

p.13 |

| 2 |

67 |

原初的世界・本源的世界(

primordial world) |

p.17 |

| 3 |

70 |

大地の創造 |

|

| 4 |

74 |

動物の創造 |

p.20 |

| 5 |

75 |

動物の消滅 |

p.26 |

| 6 |

78 |

泥の人間の創造 |

|

| 7 |

80 |

木彫による肖像の創造 |

|

| 8 |

85 |

木彫による肖像の消滅 |

|

| 9 |

91 |

日没前の七羽のオウムの誇り |

|

| 10 |

94 |

七羽のオウムとその息子たちの消滅 |

|

| 11 |

97 |

七羽のオウムの敗北 |

|

| 12 |

101 |

シパクナの功績と四百の少年たち |

|

| 13 |

105 |

シパクナの敗北 |

|

| 14 |

108 |

カブラカンの敗北 |

|

| 15 |

112 |

フナアフプーとイシュバランケーの父親の

歌 |

|

| 16 |

113 |

シバルバーを越えた、ひとりのフナアフ

プーと7人のイシュバランケーの功績 |

|

| 17 |

119 |

ひとりのフナアフプーと7人のイシュバラ

ンケーの召喚 |

|

| 18 |

122 |

ひとりのフナアフプーと7人のイシュバラ

ンケーの没落 |

|

| 19 |

128 |

「血の処女」とフナアフプーの樹 |

|

| 20 |

131 |

シバルバーから「血の処女」の上昇 |

|

| 21 |

135 |

「血の処女」とトウモロコシの奇跡 |

|

| 22 |

140 |

祖母の家におけるフナアフプーとイシュバ

ランケー |

|

| 23 |

145 |

一匹のコウモリとひとりのチョウエン |

|

| 24 |

148 |

トウモロコシ畑におけるフナアフプーとイ

シュバランケー |

|

| 25 |

152 |

フナアフプーとイシュバランケーが狩猟動

物を発見する |

|

| 26 |

154 |

フナアフプーとイシュバランケーのシバル

バーへの召喚 |

|

| 27 |

158 |

フナアフプーとイシュバランケーがシバル バーへの召喚を受け取る | |

| 28 |

160 |

フナアフプーとイシュバランケーのシバル バーへの下降 | |

| 29 |

169 |

フナアフプーとイシュバランケーが冷たい 家に入る | |

| 30 |

170 |

フナアフプーとイシュバランケーがジャ ガーの家に入る | |

| 31 |

171 |

フナアフプーとイシュバランケーが火の家 に入る | |

| 32 |

172 |

フナアフプーとイシュバランケーがコウモ リの家に入る | |

| 33 |

172 |

フナアフプーの頭の復元 |

|

| 34 |

177 |

フナアフプーとイシュバランケーの死 | |

| 35 |

180 |

フナアフプーとイシュバランケーの復活 | |

| 36 |

181 |

フナアフプーとイシュバランケーが主人た ちの前に出るように召喚 | |

| 37 |

182 |

シバルバーの主人の前でのフナアフプーと イシュバランケーの踊り | |

| 38 |

185 |

シバルバーの主人たちの没落 |

|

| 39 |

187 |

フナアフプーとイシュバランケーの奇跡を 呼ぶトウモロコシ | |

| 40 |

190 |

太陽と月と星々の神格化 |

|

| 41 |

192 |

人間性の創造 |

|

| 42 |

193 |

トウモロコシの発見 |

|

| 43 |

196 |

最初の四人の男 |

|

| 44 |

197 |

最初の男たちの奇跡の幻視 |

|

| 45 |

199 |

最初の男たちの感謝 |

|

| 46 |

200 |

神々の不快 |

|

| 47 |

201 |

キチェ王国における母親たちの創造 |

|

| 48 |

209 |

トゥランへの到着 |

|

| 49 |

211 |

祖先たちが彼らの神々を受け入れる |

|

| 50 |

213 |

祖先たちがトゥランを離れる |

|

| 51 |

214 |

民たちは彼らの火にたずねる |

|

| 52 |

216 |

民たちは自分たちの申し出に騙される |

|

| 53 |

220 |

人びとはチ・ピシャブ山に集まる |

|

| 54 |

221 |

チ・ピシャブ山上での彼らの受難 | |

| 55 |

223 |

最初の日没を待つ祖先たち |

|

| 56 |

228 |

最初の日没の到来 |

|

| 57 |

233 |

神々にささげられる供物が用意される |

|

| 58 |

238 |

供犠のために殺戮がはじまる |

|

| 59 |

240 |

民たちは神々を誘惑する計画をねる |

|

| 60 |

242 |

「欲望の女」と「嘆きの女」の誘惑 |

|

| 61 |

245 |

民たちは「塗られた外套」によって打ち負

かされる |

|

| 62 |

248 |

民たちは侮辱される |

|

| 63 |

251 |

民たちは打ち負かされる |

|

| 64 |

253 |

4人の祖先たちの死 |

|

| 65 |

256 |

祖先たちの息子たちはトゥランに旅立つ |

|

| 66 |

257 |

息子たちは支配の権威を受け入れる |

|

| 67 |

260 |

キチェ族の移動(移民) |

|

| 68 |

262 |

チー・イツマチの創設 |

|

| 69 |

266 |

クマルカーの創設 |

|

| 70 |

269 |

カヴェクの主(あるじ)たちのリスト |

|

| 71 |

271 |

ニハイブの主(あるじ)たちのリスト | |

| 72 |

272 |

アハウ・キチェの主(あるじ)たちのリス ト | |

| 73 |

273 |

ザクイックの主(あるじ)たちのリスト | |

| 74 |

274 |

クマルカーの主(あるじ)たちの栄光 | |

| 75 |

277 |

主人キカブの勝利 |

|

| 76 |

281 |

キチェの兵士、その征服地 |

|

| 77 |

284 |

貴族に列せらた者たちに与えれたリスト | |

| 78 |

285 |

神々の家々の名前 |

|

| 79 |

289 |

主人たちの神々への祈祷 |

|

| 80 |

292 |

キチェの主人たちの世代(系譜) |

|

| 81 |

293 |

カヴェク・キチェの主人たちの王朝 |

【カヴェックの9首長】(レシーノス・林

屋訳 1972:201) 1.アフポップ 2.アフポップ・カムハー 3.アフ・トヒール 4.アフ・グクマッツ 5.ニム・チョコフ・カベック 6.ポポル・ヴィナック・チトゥイ 7.ロルメット・ケフナイ 8.ポポル・ヴィナック・パ・ホム・ツァラッツ 9.ウチュチ・カムハー |

| 82 |

299 |

カヴェクの主人たちの偉大なる家 |

|

| 83 |

301 |

ニハイブの主人たちの王朝 |

【ニイハブの9首長】(レシーノス・林屋

訳 1972:201) 1.アハウ・ガレル(またはガレール) 2.アハウ・アフチック・ヴィナック 3.ガレル・カムハー 4.ニマ・カムハー 5.ウチュチ・カムハー 6.ニム・チョコフ・ニハイバブ 7.アヴィリッシュ 8.ヤコラタム 9.ウツァム・ポプ・サルクラトール 10.ニマ・ロルメット・イコルトゥシュ ※なぜ10になるのか不明(誤植?)第4部第8章注13 |

| 84 |

302 |

ニハイブの主人たちの偉大なる家 |

|

| 85 |

303 |

アハウ・キチェの主人たちの王朝 |

【アハウ・キチェーの4首長】(レシーノ

ス・林屋訳 1972:201) 1.アフチック・ヴィナック 2.アハウ・ロルメット 3.アハウ・ニム・チョコフ・アハウ 4.アハウ・ハカヴィツ |

| 86 |

304 |

アハウ・キチェの主人たちの偉大なる家 |

|

| 87 |

305 |

言葉の母たちとしての偉大なる3人の召使

い |

+++

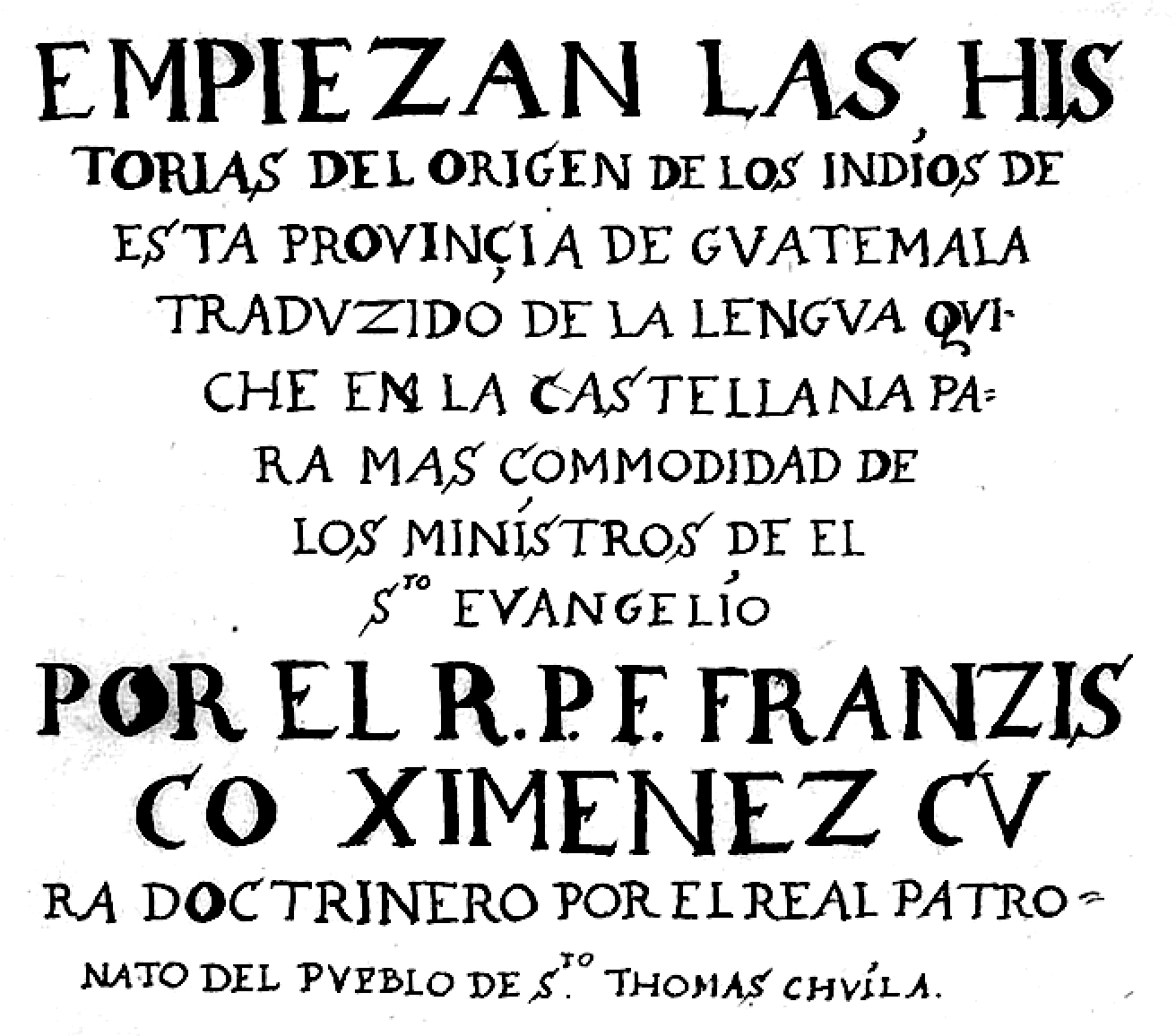

The oldest surviving written account of Popol Vuh (ms c. 1701 by Francisco Ximénez, O.P.)

★ポポル・ヴフ(Popul Vuh、Pop Vujとも)[1][2]は、メキシコのチアパス州、カンペチェ州、ユカタン州、キンタナ・ロー州、ベリーズ、ホンジュラス、エルサルバドルにも居住する マヤ民族の一つであるグアテマラのK'iche'族の神話と歴史を語るテキストである。

| Popol Vuh (also

Popul Vuh or Pop Vuj)[1][2] is a text recounting the mythology and

history of the K'iche' people of Guatemala, one of the Maya peoples who

also inhabit the Mexican states of Chiapas, Campeche, Yucatan and

Quintana Roo, as well as areas of Belize, Honduras and El Salvador. The Popol Vuh is a foundational sacred narrative of the K'iche' people from long before the Spanish conquest of the Maya.[3] It includes the Mayan creation myth, the exploits of the Hero Twins Hunahpú and Xbalanqué,[4] and a chronicle of the K'iche' people. The name "Popol Vuh" translates as "Book of the Community" or "Book of Counsel" (literally "Book that pertains to the mat", since a woven mat was used as a royal throne in ancient K'iche' society and symbolised the unity of the community).[5] It was originally preserved through oral tradition[6] until approximately 1550, when it was recorded in writing.[7] The documentation of the Popol Vuh is credited to the 18th-century Spanish Dominican friar Francisco Ximénez, who prepared a manuscript with a transcription in K'iche' and parallel columns with translations into Spanish.[6][8] Like the Chilam Balam and similar texts, the Popol Vuh is of particular importance given the scarcity of early accounts dealing with Mesoamerican mythologies. After the Spanish conquest, missionaries and colonists destroyed many documents.[9] |

ポポル・ヴフ(Popul Vuh、Pop

Vujとも)[1][2]は、メキシコのチアパス州、カンペチェ州、ユカタン州、キンタナ・ロー州、ベリーズ、ホンジュラス、エルサルバドルにも居住する

マヤ民族の一つであるグアテマラのK'iche'族の神話と歴史を語るテキストである。 ポポル・ヴフは、スペインによるマヤ征服のはるか以前からのK'iche'族の基礎となる神聖な物語であり[3]、マヤの創造神話、英雄の双子 HunahpúとXbalanquéの功績[4]、K'iche' 族の年代記を含んでいる。 「ポポル・ヴフ」という名前は、「共同体の書」または「助言の書」(文字通り「マットに関係する書」、古代K'iche'社会では織られたマットが王座と して使用され、共同体の結束を象徴していたため)と訳されている。 [ポポル・ヴフが文書化されたのは、18世紀のスペイン人ドミニコ会修道士フランシスコ・ヒメネスによるもので、彼はK'iche'語で書かれた写本と、 スペイン語に翻訳された並列コラムを作成した[6][8]。 Chilam Balamや同様のテキストと同様に、メソアメリカの神話を扱った初期の記録が少ないことから、Popol Vuhは特に重要である。スペインの征服後、宣教師と入植者は多くの文書を破壊した[9]。 |

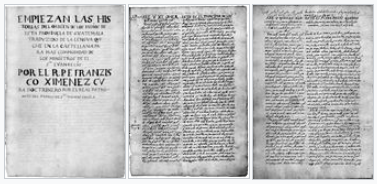

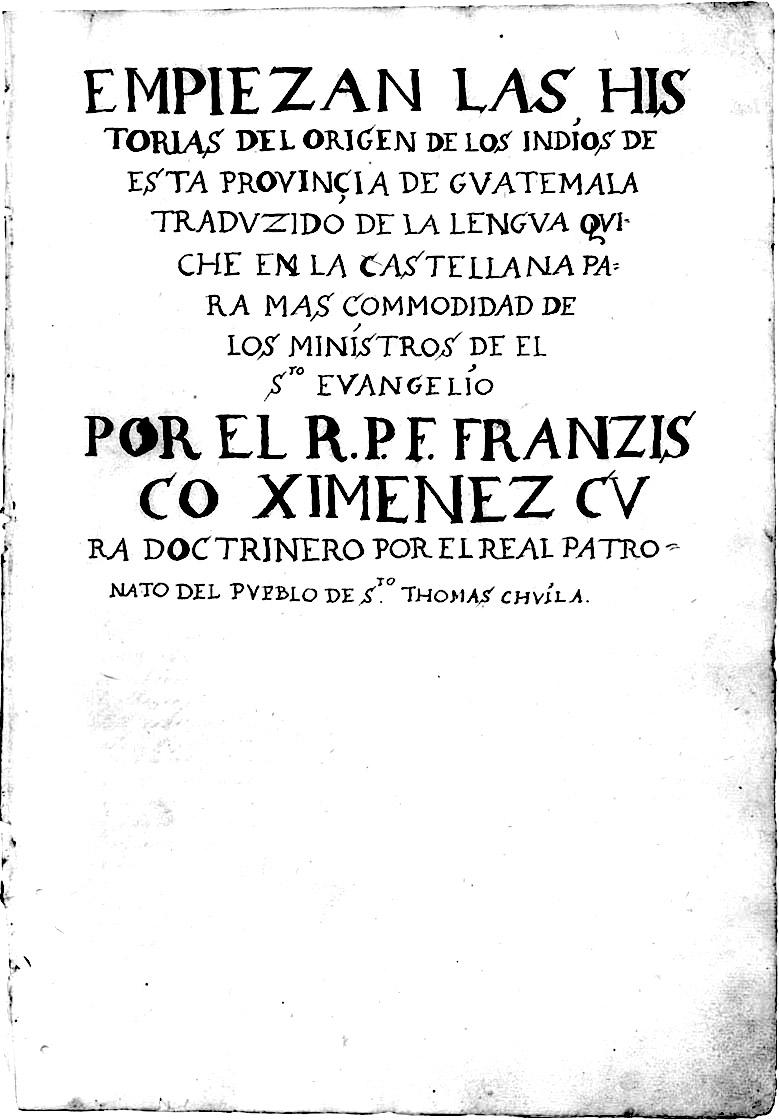

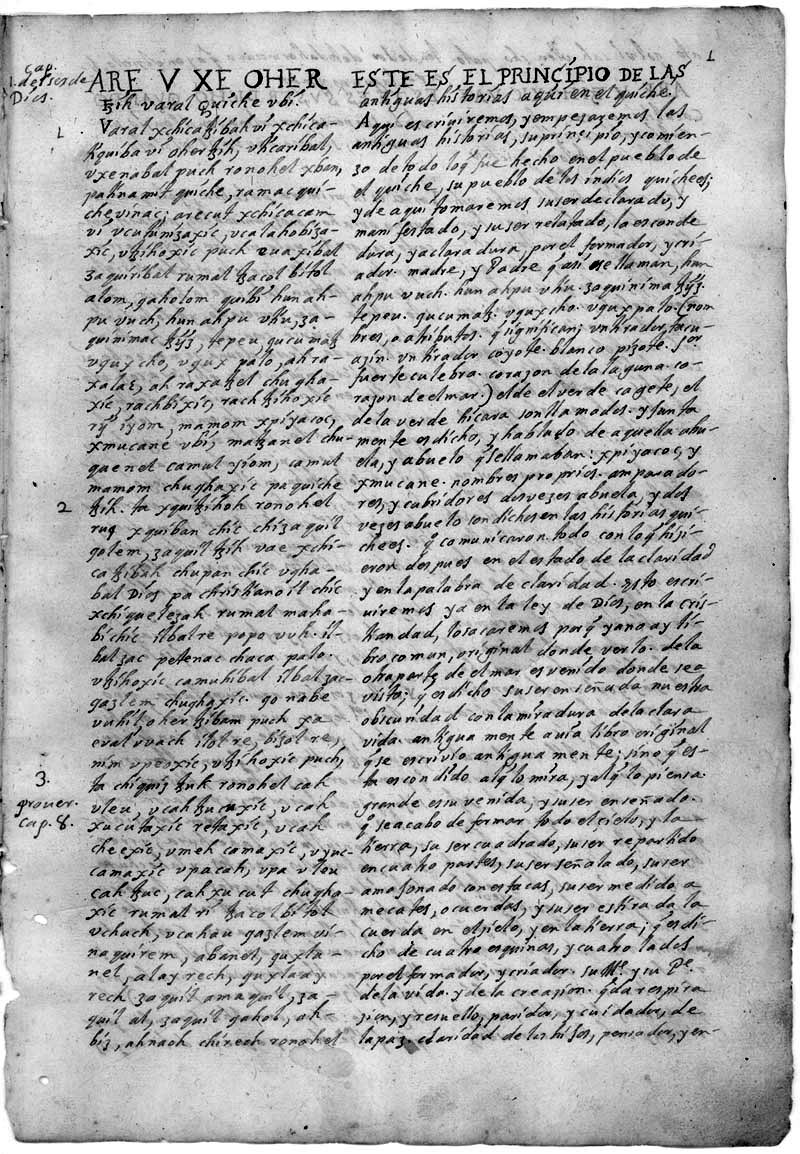

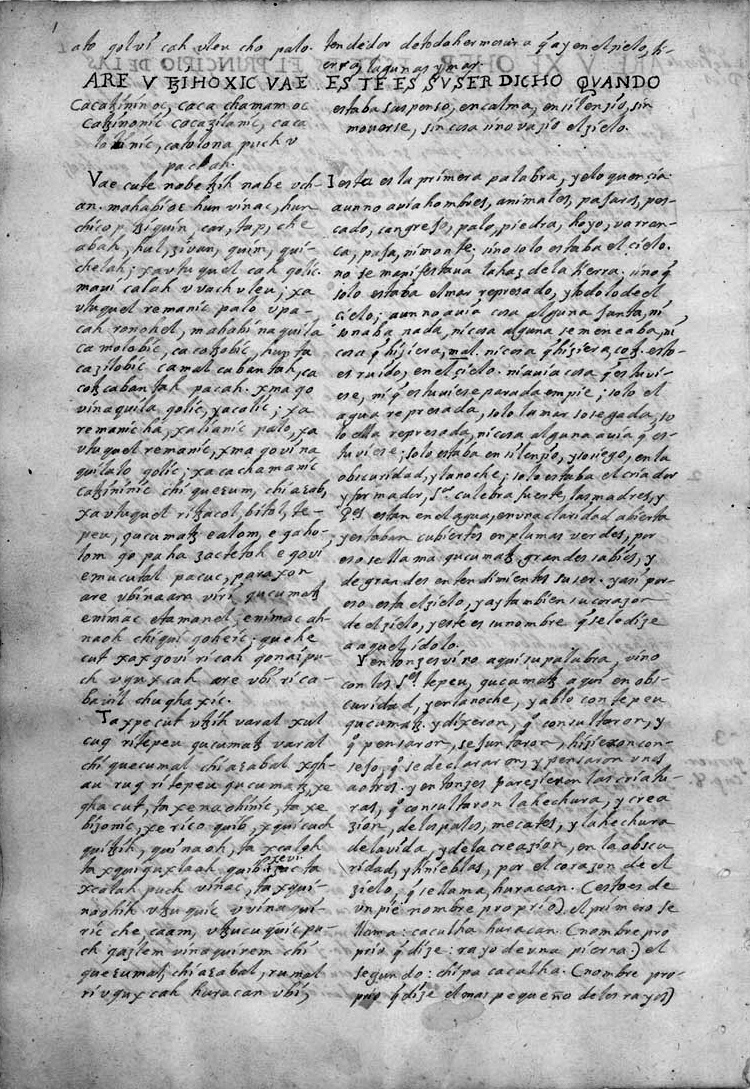

| History Priest Ximénez's manuscript In 1701, Francisco Ximénez, priest of Dominicane order, came to Santo Tomás Chichicastenango (also known as Santo Tomás Chuilá). This town was in the Quiché territory and is likely where Ximénez first recorded the work.[10] Ximénez transcribed and translated the account, setting up parallel K'iche' and Spanish language columns in his manuscript. (He represented the K'iche' language phonetically with Latin and Parra characters.) In or around 1714, Ximénez incorporated the Spanish content in book one, chapters 2–21 of his Historia de la provincia de San Vicente de Chiapa y Guatemala de la orden de predicadores. Ximénez's manuscripts were held posthumously by the Dominican Order until General Francisco Morazán expelled the clerics from Guatemala in 1829–30. At that time the Order's documents were taken over largely by the Universidad de San Carlos. From 1852 to 1855, Moritz Wagner and Carl Scherzer traveled in Central America, arriving in Guatemala City in early May 1854.[11] Scherzer found Ximénez's writings in the university library, noting that there was one particular item "del mayor interés" ('of the greatest interest'). With assistance from the Guatemalan historian and archivist Juan Gavarrete, Scherzer copied (or had a copy made of) the Spanish content from the last half of the manuscript, which he published upon his return to Europe.[12] In 1855, French Abbot Charles Étienne Brasseur de Bourbourg also came across Ximénez's manuscript in the university library. However, whereas Scherzer copied the manuscript, Brasseur apparently stole the university's volume and took it back to France.[13] After Brasseur's death in 1874, the Mexico-Guatémalienne collection containing Popol Vuh passed to Alphonse Pinart, through whom it was sold to Edward E. Ayer. In 1897, Ayer decided to donate his 17,000 pieces to The Newberry Library in Chicago, a project that was not completed until 1911. Father Ximénez's transcription-translation of Popol Vuh was among Ayer's donated items. Priest Ximénez's manuscript sank into obscurity until Adrián Recinos rediscovered it at the Newberry in 1941. Recinos is generally credited with finding the manuscript and publishing the first direct edition since Scherzer. But Munro Edmonson and Carlos López attribute the first rediscovery to Walter Lehmann in 1928.[14] Experts Allen Christenson, Néstor Quiroa, Rosa Helena Chinchilla Mazariegos, John Woodruff, and Carlos López all consider the Newberry volume to be Ximénez's one and only "original." 'Popol Vuh' is also spelled as 'Popol Vuj', its sound in Spanish use is close to German term for 'book': 'buch', in the translation of title meaning by Adrián Recinos, both phonetics and etymology connect to 'People's book', in the line of 'people' used as a synonym for the whole nation or tribe, as in 'Bible, book of Lord's people'. Father Ximénez's source Title page Preamble Creation  Father Ximénez's manuscript contains the oldest known text of Popol Vuh. It is mostly written in parallel K'iche' and Spanish as in the front and rear of the first folio pictured here. It is generally believed that Ximénez borrowed a phonetic manuscript from a parishioner for his source, although Néstor Quiroa points out that "such a manuscript has never been found, and thus Ximenez's work represents the only source for scholarly studies."[15] This document would have been a phonetic rendering of an oral recitation performed in or around Santa Cruz del Quiché shortly following Pedro de Alvarado's 1524 conquest. By comparing the genealogy at the end of Popol Vuh with dated colonial records, Adrián Recinos and Dennis Tedlock suggest a date between 1554 and 1558.[16] But to the extent that the text speaks of a "written" document, Woodruff cautions that "critics appear to have taken the text of the first folio recto too much at face value in drawing conclusions about Popol Vuh's survival."[17] If there was an early post-conquest document, one theory (first proposed by Rudolf Schuller) ascribes the phonetic authorship to Diego Reynoso, one of the signatories of the Título de Totonicapán.[18] Another possible author could have been Don Cristóbal Velasco, who, also in Titulo de Totonicapán, is listed as "Nim Chokoh Cavec" ('Great Steward of the Kaweq').[19][20] In either case, the colonial presence is clear in Popol Vuh's preamble: "This we shall write now under the Law of God and Christianity; we shall bring it to light because now the Popol Vuh, as it is called, cannot be seen any more, in which was clearly seen the coming from the other side of the sea and the narration of our obscurity, and our life was clearly seen."[21] Accordingly, the need to "preserve" the content presupposes an imminent disappearance of the content, and therefore, Edmonson theorized a pre-conquest glyphic codex. No evidence of such a codex has yet been found. A minority, however, disputes the existence of pre-Ximénez texts on the same basis that is used to argue their existence. Both positions are based on two statements by Ximénez. The first of these comes from Historia de la provincia where Ximénez writes that he found various texts during his curacy of Santo Tomás Chichicastenango that were guarded with such secrecy "that not even a trace of it was revealed among the elder ministers" although "almost all of them have it memorized."[22] The second passage used to argue pre-Ximénez texts comes from Ximénez's addendum to Popol Vuh. There he states that many of the natives' practices can be "seen in a book that they have, something like a prophecy, from the beginning of their [pre-Christian] days, where they have all the months and signs corresponding to each day, one of which I have in my possession."[23] Scherzer explains in a footnote that what Ximénez is referencing "is only a secret calendar" and that he himself had "found this rustic calendar previously in various indigenous towns in the Guatemalan highlands" during his travels with Wagner.[24] This presents a contradiction because the item which Ximénez has in his possession is not Popol Vuh, and a carefully guarded item is not likely to have been easily available to Ximénez. Apart from this, Woodruff surmises that because "Ximenez never discloses his source, instead inviting readers to infer what they wish [. . .], it is plausible that there was no such alphabetic redaction among the Indians. The implied alternative is that he or another missionary made the first written text from an oral recitation."[25] |

歴史 ヒメネス司祭の写本 1701年、ドミニカ会の司祭フランシスコ・ヒメネスがサント・トマス・チチカステナンゴ(別名サント・トマス・チュイラ)にやってきた。この町はキチェ 族の領地であり、ヒメネス(シメネス)が最初にこの作品を記録した場所と思われる[10]。ヒメネスはその記録を書き写し、翻訳し、写本にはキチェ語とスペイン語の並 列欄を設けた。(彼はK'iche'言語をラテン文字とパーラ文字で音声的に表現した)。1714年頃、ヒメネスはスペイン語の内容をHistoria de la provincia de San Vicente de Chiapa y Guatemala de la orden de predicadoresの第1巻2-21章に取り入れた。1829年から30年にかけて、フランシスコ・モラザン将軍がグアテマラから聖職者を追放する まで、シメニスの遺稿はドミニコ会によって保管されていた。この時、ドミニコ修道会の文書はサン・カルロス大学(Universidad de San Carlos)に引き継がれた。 1852年から1855年にかけて、モーリッツ・ワーグナーとカール・シェルツァーは中米を旅行し、1854年5月初旬にグアテマラ・シティに到着した [11]。シェルツァーは大学図書館でヒメネスの著作を発見し、その中に「del mayor interés」(「最大の関心事」)があることを指摘した。1855年、フランスの修道院長シャルル・エティエンヌ・ブラッスール・ド・ブルブールもま た、大学図書館でヒメネスの手稿を見つけた。1874年のブラッスールの死後、ポポル・ヴフを含むメキシコ-ガテマリエンヌ・コレクションはアルフォン ス・ピナールの手に渡り、ピナールを通じてエドワード・E・エイヤーに売却された。1897年、エイヤーは17,000点をシカゴのニューベリー図書館に 寄贈することを決めたが、このプロジェクトが完了したのは1911年のことであった。ヒメネス神父のポポル・ヴフ写本翻訳も、エアの寄贈品のひとつであっ た。 ヒメネス神父の写本は、1941年にアドリアン・レシノスがニューベリーで再発見するまで、曖昧なまま埋もれていた。レシノスは一般に、この写本を発見 し、シャーザー以来の直筆版を出版したと信じられている。しかし、マンロ・エドモンソンとカルロス・ロペスは、最初の再発見は1928年のウォルター・ レーマンであるとしている[14]。専門家のアレン・クリステンソン、ネストル・キロア、ロサ・ヘレナ・チンチラ・マサリエゴス、ジョン・ウッドラフ、カ ルロス・ロペスは、いずれもニューベリーの本がヒメネスの唯一無二の 「オリジナル 」であると考えている。 ポポル・ヴフ'は'Popol Vuj'とも綴られ、スペイン語で使われるその音はドイツ語で'本'を意味する'buch'に近く、アドリアン・レシーノスによるタイトルの意味の翻訳で は、音韻と語源の両方が'People's book'につながり、'Bible, book of Lord's people'のように'people'が国家や部族全体の同義語として使われる。 ヒメネス神父の出典 タイトルページ 前文 天地創造  Ximénez神父の写本には、ポポル・ヴフ最古のテキストが含まれている。写真の第1フォリオの前後にあるように、ほとんどがK'iche'語とスペイ ン語で並行して書かれている。(下に拡大図版あります) 一般に、ヒメネスは教区の人から音声写本を借りて典拠としたと考えられているが、ネストール・キロアは「そのような写本は発見されておらず、したがってヒ メネスの著作が学術研究の唯一の典拠となっている」と指摘している[15]。この文書は、ペドロ・デ・アルバラードが1524年に征服した直後にサンタ・ クルス・デル・キチェ周辺で行われた口誦を音声化したものであろう。Adrián RecinosとDennis Tedlockは、『ポポル・ヴフ』巻末の系図を日付の入った植民地時代の記録と比較することで、1554年から1558年の間であることを示唆している [16]。しかし、本文が「書かれた」文書について語っている限りにおいて、Woodruffは「批評家たちは『ポポル・ヴフ』の存続について結論を導き 出す際に、最初のフォリオのレクトの文章を額面通りに受け取りすぎているようだ」と警告している。 「17] もし征服後の初期の文書があったとすれば、(ルドルフ・シュラーによって最初に提唱された)一説によると、発音上の作者はTítulo de Totonicapánの署名者の一人であるディエゴ・レイノソであるとされている。 [19][20] いずれにせよ、植民地時代の存在はポポル・ヴフの前文に明らかである: 「というのも、ポポル・ヴフ(Popol Vuh)と呼ばれる書物はもはや見ることができず、その中には海の向こうからの来訪とわれわれの無名についての叙述がはっきりと見られ、われわれの生活も はっきりと見られたからである。そのような写本の証拠はまだ見つかっていない。 しかし少数派は、シメネス以前の写本の存在を主張するのと同じ根拠で、その存在に異議を唱えている。どちらの立場も、キシメネスの2つの記述に基づいてい る。その1つ目は『Historia de la provincia』にあるもので、シメネスがサント・トマス・チチカステナンゴで司祭を務めていた時に様々なテキストを発見したが、それは「長老の聖職 者たちの間ではその痕跡さえも明らかにされなかった」ほど秘密裏に守られていたにもかかわらず、「ほとんどすべての聖職者たちがそれを暗記していた」と記 している[22]。シメネス以前のテキストを論証するために用いられる2つ目の文章は、シメネスによる『Popol Vuh』の補遺にある。そこでは、原住民の慣習の多くが「彼らの(キリスト教以前の)日々の始まりから持っている、予言のような書物に見ることができる。 「23]シェルザーは脚注で、シメネスが言及しているのは「秘密の暦に過ぎない」と説明し、彼自身はワグナーとの旅行中に「以前グアテマラ高地の様々な先 住民の町でこの素朴な暦を発見した」と述べている[24]。シメネスが所持しているものはポポル・ヴフではないし、慎重に保管されているものがシメネスが 容易に入手できたとは考えられないので、これは矛盾を呈している。これとは別に、ウッドラフは、「シメネスは出典を明かさず、読者が勝手に推測するよう促 している(中略)インディオの間では、このようなアルファベットの再編集はなかったと考えるのが妥当である」と推測している。つまり、彼か他の宣教師が、 口誦から最初の文章を作ったということである」[25]。 |

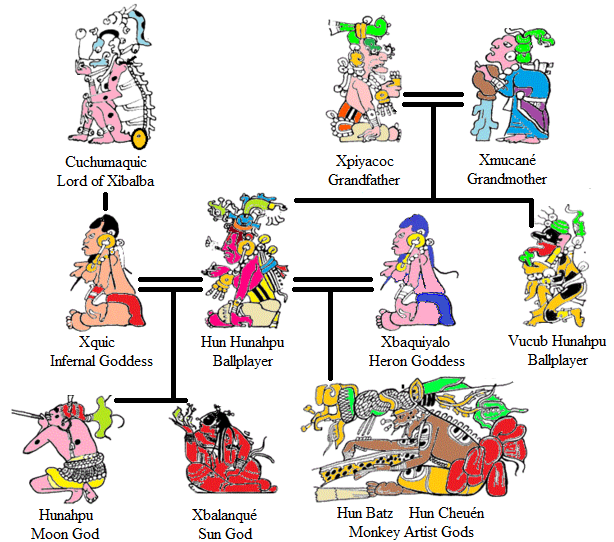

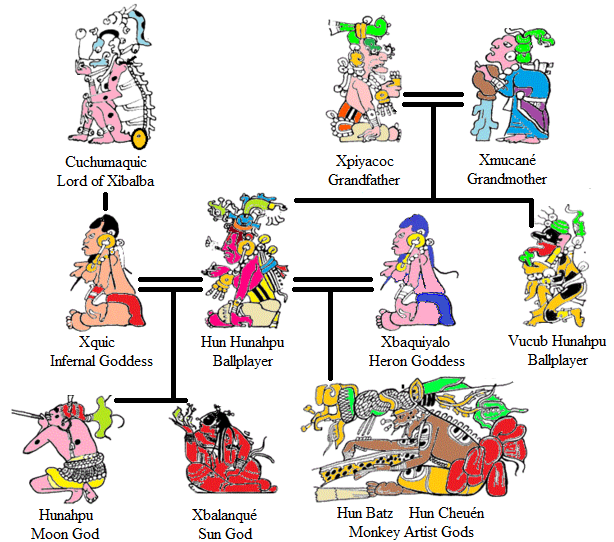

Story of Hunahpú and Xbalanqué Tonsured Maize God and Spotted Hero Twin Many versions of the legend of the Hero Twins Hunahpú and Xbalanqué circulated through the Maya peoples[citation needed], but the story that survives was preserved by the Dominican priest Francisco Ximénez[6] who translated the document between 1700 and 1715.[26] Maya deities in the Post-Classic codices differ from the earlier versions described in the Early Classic period. In Mayan mythology Hunahpú and Xbalanqué are the second pair of twins out of three, preceded by Hun-Hunahpú and his brother Vucub-Hunahpú, and precursors to the third pair of twins, Hun Batz and Hun Chuen. In the Popol Vuh, the first set of twins, Hun-Hunahpú and Vucub-Hanahpú were invited to the Mayan Underworld, Xibalba, to play a ballgame with the Xibalban lords. In the Underworld the twins faced many trials filled with trickery; eventually they fail and are put to death. The Hero Twins, Hunahpú and Xbalanqué, are magically conceived after the death of their father, Hun-Hunahpú, and in time they return to Xibalba to avenge the deaths of their father and uncle by defeating the Lords of the Underworld. |

フナプーとエクスバランケの物語 緊張したトウモロコシの神と斑点のある英雄の双子 英雄の双子フナンプーとスバランケの伝説の多くのバージョンがマヤ民族[要出典]を介して循環したが、現存する物語は、1700年から1715年の間に文 書を翻訳したドミニコ会司祭フランシスコヒメネス[6]によって保存された[26]。ポスト古典コーデックスのマヤの神々は、初期古典時代に記載されてい る以前のバージョンとは異なります。マヤ神話では、フナフプとエクスバランケは3組の双子のうちの2組目であり、フン・フナフプとその兄弟であるブクブ・ フナフプがその前身であり、3組目の双子であるフン・バッツとフン・チュエンの前身である。ポポル・ヴフ』では、最初の双子のフン=フナフプとブクブ=フ ナフプは、マヤの冥界クシバルバに招かれ、クシバルバの領主たちと球技をした。冥界で双子は策略に満ちた多くの試練に直面し、最終的に失敗して死刑にな る。英雄の双子であるフナプーとエクスバランケは、父フナプーの死後、魔法で妊娠し、やがて彼らは父と叔父の仇を討つため、冥界の支配者たちを倒してキシ バルバに戻る。 |

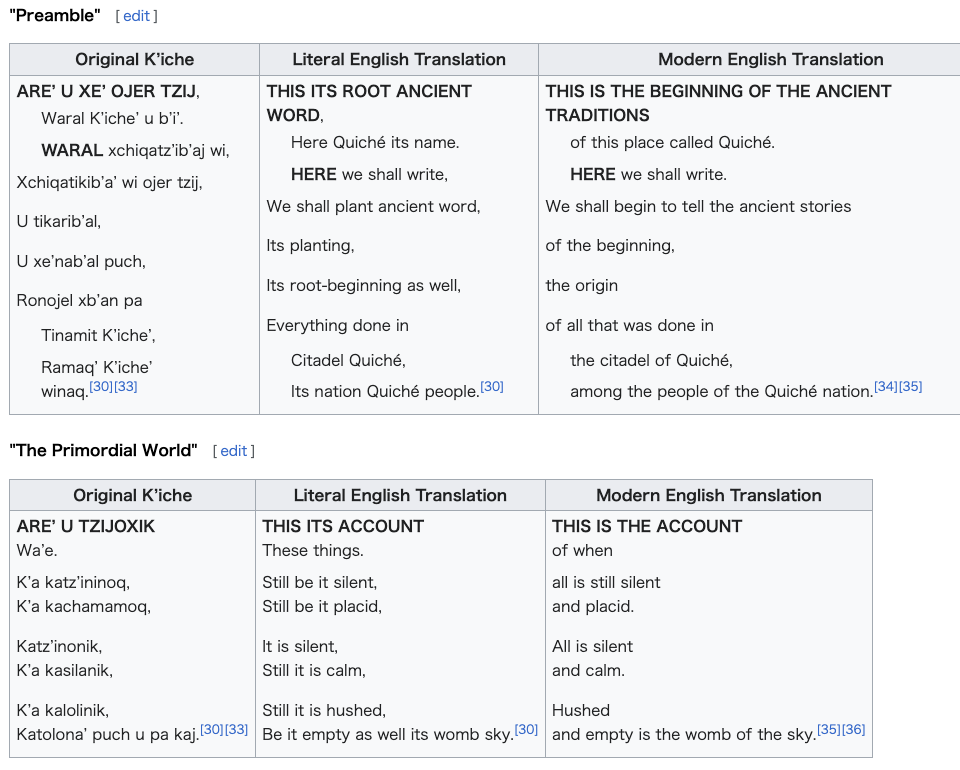

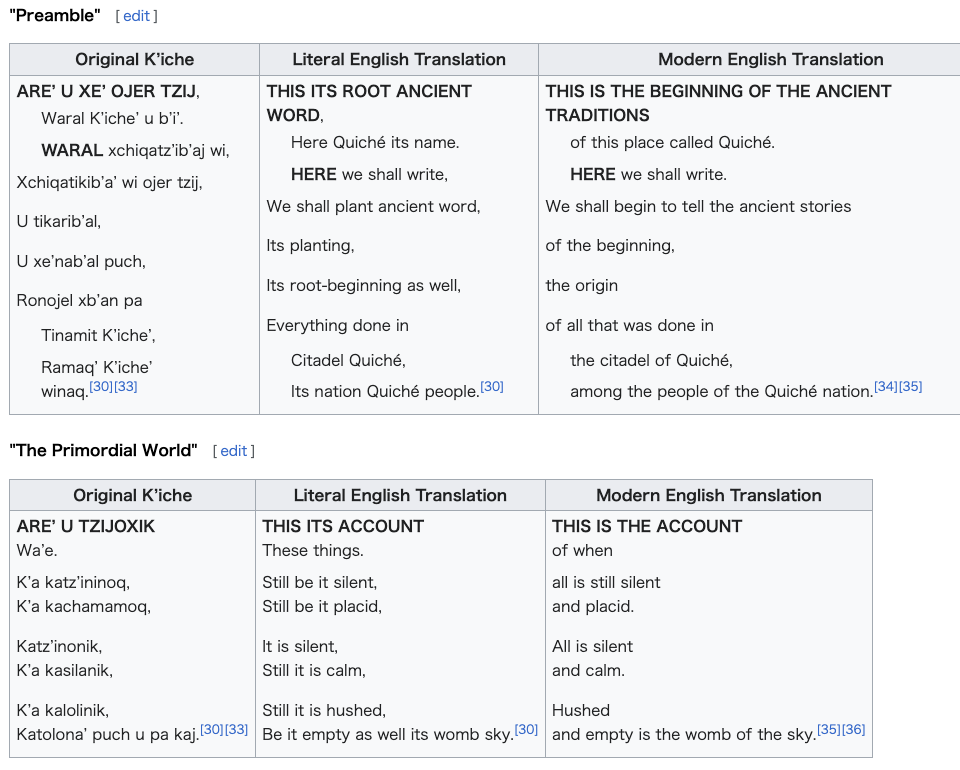

Popol Vuh encompasses a range of subjects that includes creation, ancestry, history, and cosmology. There are no content divisions in the Newberry Library's holograph, but popular editions have adopted the organization imposed by Brasseur de Bourbourg in 1861 in order to facilitate comparative studies.[27] Though some variation has been tested by Dennis Tedlock and Allen Christenson, editions typically take the following form:  A family tree of gods and demigods. Vertical lines indicate descent Horizontal lines indicate siblings Double lines indicate marriage Preamble Introduction to the piece that introduces Xpiyacoc and Xmucane, the purpose for writing the Popol Vuh, and the measuring of the earth.[28] Book One Account of the creation of living beings. Animals were created first, followed by humans. The first humans were made of earth and mud, but crumbled. The second humans were created from wood, but they did not function well and were washed away in a flood and killed by animals.[29] Vucub-Caquix ascends.[29] Book Two The Hero Twins plan to kill Vucub-Caquix and his sons, Zipacna and Cabracan.[29] They succeed, "restoring order and balance to the world."[29] Book Three The father and uncle of The Hero Twins, Hun Hunahpu and Vucub Hunahpu, sons of Xmucane and Xpiacoc, are murdered at a ball game in Xibalba.[29] Hun Hunahpu's head is placed in a calabash tree, where it spits in the hand of Xquiq, impregnating her.[29] She leaves the underworld to be with her mother-in-law, Xmucane.[29] Her sons then challenge the Lords who killed their father and uncle, succeeding and becoming the sun and the moon.[29] Book Four Humans are successfully created from maize.[29] The gods give them morality in order to keep them loyal.[29] Later, they give the humans wives to make them content.[29] This book also describes the movement of the K'che' and includes the introduction of Gucumatz.[29] Excerpts A visual comparison of two sections of the Popol Vuh are presented below and include the original Kʼiche, literal English translation, and modern English translation as shown by Allen Christenson.[30][31][32]  |

ポポル・ヴフには、創造、祖先、歴史、宇宙論など、さまざまな主題が含まれている。ニューベリー図書館のホログラフには内容的な区分はないが、一般的な版 では比較研究を容易にするために、1861年にブラッスール・ド・ブルブールが課した構成を採用している[27]。 デニス・テドロックとアレン・クリステンソンによっていくつかのバリエーションが検証されているが、版では一般的に次のような形式をとっている:  神々と半神の家系図。 縦線は子孫を示す。 横線は兄弟を示す。 二重線は結婚を示す。 前文 XpiyacocとXmucane、ポポル・ヴフを書いた目的、地球の測定などを紹介する作品の序文[28]。 第一巻 生物の創造に関する記述。動物が最初に創造され、次に人間が創造された。最初の人間は土と泥で作られたが、崩れてしまった。二番目の人間は木から作られた が、うまく機能せず、洪水で流され、動物に殺された[29]。 ヴクブ=カキックスは昇天する[29]。 第二巻 英雄の双子はヴクブ=カキックスとその息子ジパクナとカブラカンの殺害を計画する[29]。 彼らは成功し、「世界に秩序と均衡を取り戻す」[29]。 第3巻 英雄の双子の父と叔父、XmucaneとXpiacocの息子であるHun HunahpuとVucub HunahpuがXibalbaの球技大会で殺害される[29]。 フン・フナプの首は瓢箪の木の中に置かれ、Xquiqの手に唾を吐きかけ、彼女を孕ませる[29]。 彼女は義母であるXmucaneと一緒になるために冥界を去る[29]。 彼女の息子たちは父と叔父を殺した諸侯に挑み、成功して太陽と月になる[29]。 第4巻 トウモロコシから人間が創造される[29]。 神々は人間に忠誠を誓わせるために道徳を与える[29]。 その後、神々は人間を満足させるために妻を与える[29]。 この本ではK'che'の動きも描かれ、Gucumatzの紹介もある[29]。 抜粋 ポポル・ヴフの2つのセクションの視覚的な比較が以下に示されており、オリジナルのKʼiche、直訳された英語、Allen Christensonによって示された現代英語訳が含まれている[30][31][32]。  |

| Modern history Modern editions Since Brasseur's and Scherzer's first editions, the Popol Vuh has been translated into many other languages besides its original K'che'.[37] The Spanish edition by Adrián Recinos is still a major reference, as is Recino's English translation by Delia Goetz. Other English translations[38] include those of Victor Montejo,[39] Munro Edmonson (1985), and Dennis Tedlock (1985, 1996).[40] Tedlock's version is notable because it builds on commentary and interpretation by a modern K'che' daykeeper, Andrés Xiloj. Augustín Estrada Monroy published a facsimile edition in the 1970s and Ohio State University has a digital version and transcription online. Modern translations and transcriptions of the K'che' text have been published by, among others, Sam Colop (1999) and Allen J. Christenson (2004). In 2018, The New York Times named Michael Bazzett's new translation as one of the ten best books of poetry of 2018.[41] The tale of Hunahpu and Xbalanque has also been rendered as an hour-long animated film by Patricia Amlin.[42][43] Contemporary culture The Popol Vuh continues to be an important part in the belief system of many K'che'.[citation needed] Although Catholicism is generally seen as the dominant religion, some believe that many natives practice a syncretic blend of Christian and indigenous beliefs. Some stories from the Popol Vuh continued to be told by modern Maya as folk legends; some stories recorded by anthropologists in the 20th century may preserve portions of the ancient tales in greater detail than the Ximénez manuscript.[citation needed] On August 22, 2012, the Popol Vuh was declared intangible cultural heritage of Guatemala by the Guatemalan Ministry of Culture.[44] Reflections in Western culture Since its rediscovery by Europeans in the nineteenth century, the Popol Vuh has attracted the attention of many creators of cultural works. Mexican muralist Diego Rivera produced a series of watercolors in 1931 as illustrations for the book. In 1934, the early avant-garde Franco-American composer Edgard Varèse wrote his Ecuatorial, a setting of words from the Popol Vuh for bass soloist and various instruments. The planet of Camazotz in Madeleine L'Engle's A Wrinkle in Time (1962) is named for the bat-god of the hero-twins story. In 1969 in Munich, Germany, keyboardist Florian Fricke—at the time ensconced in Mayan myth—formed a band named Popol Vuh with synth player Frank Fiedler and percussionist Holger Trulzsch. Their 1970 debut album, Affenstunde, reflected this spiritual connection. Another band by the same name, this one of Norwegian descent, formed around the same time, its name also inspired by the K'che' writings. The text was used by German film director Werner Herzog as extensive narration for the first chapter of his movie Fata Morgana (1971). Herzog and Florian Fricke were life long collaborators and friends. The Argentinian composer Alberto Ginastera began writing his symphonic work Popol Vuh in 1975, but neglected to complete the piece before his death in 1983. The myths and legends included in Louis L'Amour's novel The Haunted Mesa (1987) are largely based on the Popol Vuh. The Popol Vuh is referenced throughout Robert Rodriguez's television show From Dusk till Dawn: The Series (2014). In particular, the show's protagonists, the Gecko Brothers, Seth and Richie, are referred to as the embodiment of Hunahpú and Xbalanqué, the hero twins, from the Popol Vuh. |

近代史 現代版 ブラッスールとシェルツァーの初版以来、ポポル・ヴフは原典のK'che'以外にも多くの言語に翻訳されている[37]。アドリアン・レシノスによるス ペイン語版は、デリア・ゲッツによるレシノの英訳と同様に、今でも主要な参考文献である。他の英訳[38]には、Victor Montejo、[39]Munro Edmonson (1985)、Dennis Tedlock (1985, 1996)のものがある[40]。Tedlockの版は、現代のK'che'デイキーパーであるAndrés Xilojによる解説と解釈に基づいている点で注目に値する。Augustín Estrada Monroyは1970年代にファクシミリ版を出版し、Ohio State Universityはデジタル版とトランスクリプションをオンラインで公開している。K'che'テキストの現代的な翻訳とトランスクリプションは、 とりわけSam Colop (1999)とAllen J. Christenson (2004)によって出版されている。2018年、ニューヨーク・タイムズ紙はマイケル・バゼットの新訳を2018年の詩集ベスト10に選んだ[41]。 フナプとエクスバランケの物語はパトリシア・アムリンによって1時間のアニメーション映画にもなっている[42][43]。 現代文化 ポポル・ヴフは、多くのK'che'の信仰体系において重要な位置を占め続けている[要出典]。一般的にはカトリックが支配的な宗教と考えられている が、多くの原住民はキリスト教と土着の信仰を融合させたシンクレティックな信仰を実践しているという説もある。20世紀に人類学者によって記録された物語 の中には、シメネス手稿よりも詳細に古代の物語の一部を保存しているものもある[要出典]。2012年8月22日、ポポル・ヴフはグアテマラ文化省によっ てグアテマラの無形文化遺産に登録された[44]。 西洋文化への反映 19世紀にヨーロッパ人によって再発見されて以来、ポポル・ヴフは多くの文化作品の創作者の注目を集めてきた。 メキシコの壁画家ディエゴ・リベラは、1931年にこの本の挿絵として一連の水彩画を制作した。 1934年には、初期の前衛的なフランコ系アメリカ人作曲家エドガール・ヴァレーズが、低音ソリストと様々な楽器のためにポポル・ヴフの言葉を作曲した。 マドレーン・レングルの『A Wrinkle in Time』(1962年)に登場する惑星カマゾッツは、主人公と双子の物語に登場するコウモリの神にちなんで名づけられた。 1969年、ドイツのミュンヘンで、当時マヤ神話にどっぷり浸かっていたキーボード奏者のフロリアン・フリックが、シンセ奏者のフランク・フィードラー、 パーカッショニストのホルガー・トゥルルシュとバンド「ポポル・ヴフ」を結成した。彼らの1970年のデビュー・アルバム『Affenstunde』は、 このスピリチュアルなつながりを反映している。ノルウェー系の同名バンドも同時期に結成され、その名前もK'che'の文章にインスパイアされたもの だった。 このテキストは、ドイツの映画監督ヴェルナー・ヘルツォークが映画『ファタ・モルガナ』(1971年)の第1章のナレーションとして使用した。ヘルツォー クとフローリアン・フリッケは生涯の共同制作者であり、友人でもあった。 アルゼンチンの作曲家アルベルト・ジナステラは1975年に交響曲『ポポル・ヴフ』を書き始めたが、1983年に亡くなるまで完成させることができなかっ た。 ルイ・ラムールの小説『The Haunted Mesa』(1987年)に登場する神話や伝説は、その大部分がポポル・ヴフに基づいている。 ポポル・ヴフは、ロバート・ロドリゲスのテレビ番組『From Dusk till Dawn: The Series』(2014年)の随所で言及されている。特に、この番組の主人公であるヤモリ兄弟のセスとリッチーは、ポポル・ヴフに登場する英雄の双子、 フナプー(Hunahpú)とエクスバランケ(Xbalanqué)を体現していると言われている。 |

| Antecedents in Maya iconography Contemporary archaeologists (first of all Michael D. Coe) have found depictions of characters and episodes from Popol Vuh on Mayan ceramics and other art objects (e.g., the Hero Twins, Howler Monkey Gods, the shooting of Vucub-Caquix and, as many believe, the restoration of the Twins' dead father, Hun Hunahpu).[45] The accompanying sections of hieroglyphical text could thus, theoretically, relate to passages from the Popol Vuh. Richard D. Hansen found a stucco frieze depicting two floating figures that might be the Hero Twins[46][47][48][49] at the site of El Mirador.[50] Following the Twin Hero narrative, mankind is fashioned from white and yellow corn, demonstrating the crop's transcendent importance in Maya culture. To the Maya of the Classic period, Hun Hunahpu may have represented the maize god. Although in the Popol Vuh his severed head is unequivocally stated to have become a calabash, some scholars believe the calabash to be interchangeable with a cacao pod or an ear of corn. In this line, decapitation and sacrifice correspond to harvesting corn and the sacrifices accompanying planting and harvesting.[51] Planting and harvesting also relate to Maya astronomy and calendar, since the cycles of the moon and sun determined the crop seasons.[52] |

マヤの図像における前身 現代の考古学者たち(特にマイケル・D・コー)は、マヤの陶磁器やその他の美術品にポポル・ヴフに登場する人物やエピソードを描いているのを発見している (例えば、英雄の双子、遠吠え猿の神々、ヴクブ=カキックスの射殺、そして多くの人が信じているように、双子の死んだ父親フン・フナプの修復)[45]。 リチャード・D・ハンセンは、エル・ミラドール遺跡で双子の英雄と思われる2人の浮遊する人物を描いた漆喰のフリーズを発見した[46][47][48] [49]。 双子の英雄の物語に従って、人類は白と黄色のトウモロコシから作られ、マヤ文化における作物の超越的な重要性を示している。古典期のマヤにとって、フン・ フナプはトウモロコシの神を象徴していたのかもしれない。ポポル・ヴフ』では、フン・フナプの切断された頭部は瓢箪になったと明確に記されているが、瓢箪 はカカオのさややトウモロコシの穂と交換可能であると考える学者もいる。このラインでは、断頭と犠牲はトウモロコシの収穫と、植え付けと収穫に伴う犠牲と 対応している[51]。植え付けと収穫はまた、月と太陽のサイクルが作物の季節を決定することから、マヤの天文学と暦にも関連している[52]。 |

| Notable editions 1857. Scherzer, Carl, ed. (1857). Las historias del origen de los indios de esta provincia de Guatemala. Vienna: Carlos Gerold e hijo. 1861. Brasseur de Bourbourg; Charles Étienne (eds.). Popol vuh. Le livre sacré et les mythes de l'antiquité américaine, avec les livres héroïques et historiques des Quichés. Paris: Bertrand. 1944. Popol Vuh: das heilige Buch der Quiché-Indianer von Guatemala, nach einer wiedergefundenen alten Handschrift neu übers. und erlautert von Leonhard Schultze. Schultze Jena, Leonhard (trans.). Stuttgart, Germany: W. Kohlhammer. OCLC 2549190. 1947. Recinos, Adrián (ed.). Popol Vuh: las antiguas historias del Quiché. Mexico: Fondo de Cultura Económica. 1950. Goetz, Delia; Morley, Sylvanus Griswold (eds.). Popol Vuh: The Sacred Book of the Ancient Quiché Maya By Adrián Recinos (1st ed.). Norman: University of Oklahoma Press. 1971. Edmonson, Munro S. (ed.). The Book of Counsel: The Popol-Vuh of the Quiche Maya of Guatemala. Publ. no. 35. New Orleans: Middle American Research Institute, Tulane University. OCLC 658606. 1973. Estrada Monroy, Agustín (ed.). Popol Vuh: empiezan las historias del origen de los índios de esta provincia de Guatemala (Edición facsimilar ed.). Guatemala City: Editorial "José de Piñeda Ibarra". OCLC 1926769. 1985. Popol Vuh: the Definitive Edition of the Mayan Book of the Dawn of Life and the Glories of Gods and Kings, with commentary based on the ancient knowledge of the modern Quiché Maya. Tedlock, Dennis (translator). New York: Simon & Schuster. 1985. ISBN 0-671-45241-X. OCLC 11467786. 1999. Colop, Sam, ed. (1999). Popol Wuj: versión poética K'che'. Quetzaltenango; Guatemala City: Proyecto de Educación Maya Bilingüe Intercultural; Editorial Cholsamaj. ISBN 99922-53-00-2. OCLC 43379466. (in K'iche') 2004. Popol Vuh: Literal Poetic Version: Translation and Transcription. Christenson, Allen J. (trans.). Norman: University of Oklahoma Press. March 2007. ISBN 978-0-8061-3841-1. 2007. Popol Vuh: The Sacred Book of the Maya. Christenson, Allen J. (trans.). Norman: University of Oklahoma Press. 2007. ISBN 978-0-8061-3839-8. 2007. Poopol Wuuj - Das heilige Buch des Rates der K´ichee´-Maya von Guatemala. Rohark, Jens (trans.). Docupoint-Verlag. 2007. ISBN 978-3-939665-32-8. 2018. The Popol Vuh: A New Verse Translation. Bazzett, Michael (trans.). Seedbank Books. 2018. ISBN 978-1-5713-1468-0. |

主な版 1857年 シェルツァー、カール編 (1857年)。 グアテマラ州の先住民の起源の物語。ウィーン:カルロス・ゲロルド・イ・イーホ。 1861年 ブラスール・ド・ブールブール、シャルル・エティエンヌ編。ポポル・ヴフ。古代アメリカ神話と聖典、キチェ族の英雄的・歴史的文献。パリ: Bertrand. 1944. Popol Vuh: das heilige Buch der Quiché-Indianer von Guatemala, nach einer wiedergefundenen alten Handschrift neu übers. und erlautert von Leonhard Schultze. Schultze Jena, Leonhard (trans.). Stuttgart, Germany: W. Kohlhammer. OCLC 2549190. 1947. Recinos, Adrián (ed.). Popol Vuh: las antiguas historias del Quiché. Mexico: Fondo de Cultura Económica. 1950. Goetz, Delia; Morley, Sylvanus Griswold (eds.). Popol Vuh: The Sacred Book of the Ancient Quiché Maya By Adrián Recinos (1st ed.). Norman: University of Oklahoma Press. 1971. Edmonson, Munro S. (ed.). The Book of Counsel: The Popol-Vuh of the Quiche Maya of Guatemala. Publ. no. 35. New Orleans: Middle American Research Institute, Tulane University. OCLC 658606. 1973. Estrada Monroy, Agustín (ed.). Popol Vuh: empiezan las historias del origen de los índios de esta provincia de Guatemala (Edición facsimilar ed.). Guatemala City: Editorial 「José de Piñeda Ibarra」. OCLC 1926769. 1985. Popol Vuh: the Definitive Edition of the Mayan Book of the Dawn of Life and the Glories of Gods and Kings, with commentary based on the ancient knowledge of the modern Quiché Maya. Tedlock, Dennis (translator). New York: Simon & Schuster. 1985. ISBN 0-671-45241-X. OCLC 11467786. 1999. Colop, Sam, ed. (1999). Popol Wuj: versión poética K'che'. Quetzaltenango; Guatemala City: Proyecto de Educación Maya Bilingüe Intercultural; Editorial Cholsamaj. ISBN 99922-53-00-2. OCLC 43379466. (in K'iche') 2004. 『ポポル・ヴフ:文字詩編:翻訳と転写』。クリストセン、アレン J.(訳)。ノーマン:オクラホマ大学出版。2007年3月。ISBN 978-0-8061-3841-1。 2007. 『ポポル・ヴフ:マヤの聖典』。クリストセン、アレン J.(訳)。ノーマン:オクラホマ大学出版。2007. ISBN 978-0-8061-3839-8. 2007. Poopol Wuuj - Das heilige Buch des Rates der K´ichee´-Maya von Guatemala. ローハーク、イェンス(翻訳)。Docupoint-Verlag。2007. ISBN 978-3-939665-32-8. 2018. 『ポポル・ヴフ:新訳詩編』。Bazzett, Michael (trans.). Seedbank Books. 2018. ISBN 978-1-5713-1468-0. |

| El Mirador, Guatemala |

|

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Popol_Vuh |

|

| Francísco Ximénez

(November 28, 1666 – c. 1729) was a Dominican priest who is known for

his conservation of an indigenous Maya narrative known today as the

Popol Vuh. John Woodruff has noted that there remains very few

biographical data about Ximénez.[1] Aside from the year of his birth,

baptismal records do not agree on the actual date of his birth, and the

year of his death is less certain, either in late 1729 or early 1730.

He enrolled in a seminary in Spain and arrived in the New World in

1688, where he completed his novitiate. Father Ximénez's sacerdotal service began in 1691 in San Juan Sacatepéquez and San Pedro de las Huertas in present-day Guatemala where he learned Kaqchikel, a Mayan language. In December 1693, Ximénez began serving as the Doctrinero of San Pedro de las Huertas. He continued in this office for at least ten years during which time he was transferred to Santo Tomás Chichicastenango (also known as Chuilá) between 1701–1703. He was also the curate of Rabinal from 1704 to 1714 and further served as the Vicario and Predicador-General of the same district as early as 1705. His time in Santo Tomás Chichicastennago from 1701 to 1703 is probably when he transcribed and translated the Popol Vuh (see image on the right — Ximénez does not give it its modern title). Later in 1715, Ximénez included a monolingual redaction in his commissioned Historia de la provincia de San Vicente de Chiapa y Gvatemala. He has two other known writings, Primera parte de el tesoro de las lengvas 3a3chiquel Qviche y 4,vtvhil and Historia natural del Reino de Guatemala.[2] |

フランシスコ・ヒメネス(1666年11月28日 -

1729年頃)はドミニコ会の司祭であり、今日ポポル・ヴーとして知られる先住民マヤの叙事詩を保存したことで知られる。ジョン・ウッドラフは、ヒメネス

に関する伝記的資料が極めて少ないと指摘している。[1]

誕生年を除き、洗礼記録は実際の生年月日を一致させておらず、没年も1729年末か1730年初頭と不確かである。彼はスペインの神学校に入学し、

1688年に新大陸に到着して修練期を終えた。 シメネス神父の司祭としての奉仕は1691年、現在のグアテマラにあるサン・フアン・サカテペケスとサン・ペドロ・デ・ラス・ウエルタスで始まった。そこ で彼はマヤ語の一種であるカクチケル語を学んだ。1693年12月、シメネスはサン・ペドロ・デ・ラス・ウエルタスのドクトリネロ(教理指導者)としての 職務を開始した。この職務は少なくとも10年間継続し、その間1701年から1703年にかけてサント・トマス・チチカステナンゴ(チュイラとも呼ばれ る)へ異動となった。また1704年から1714年までラビナルの助祭を務め、さらに早くも1705年には同地区の副司祭兼説教総長を兼任した。 1701年から1703年にかけてのサン・トマス・チチカステナンゴ在任中に、彼はおそらく『ポポル・ヴフ』を写本し翻訳した(右の画像参照 ― シメネスは現代の題名を与えていない)。その後1715年、シメネスは委託された『サン・ビセンテ・デ・キアパ・イ・グアテマラ州史』に単言語版を収録し た。他に『キチェ語とグアテマラ語の言語宝庫第一部』と『グアテマラ王国自然誌』の2著作が確認されている。[2] |

| 1. "There is very little

biographical information on Father Ximénez. The information presented

here is compiled from Rodríguez Cabal, Ximénez's own Historia de la

provincia, and Tedlock" (Woodruff 12). 2. Note that the Parra characters for the tresillo and quartillo have been approximated with Arabic numerals. |

1. 「シメネス神父に関する伝記情報は極めて少ない。ここに提示する情報は、ロドリゲス・カバル、シメネス自身の『ヒストリア・デ・ラ・プロビンシア』、そしてテッドロックの著作からまとめたものである」(ウッドラフ 12)。 2. トレシーヨとクアルティーヨのパラ文字表記は、アラビア数字で近似されていることに留意せよ。 |

| References Rodríguez Cabal, Juan. Apuntes para la vida del m.r.p. presentado y predicador general fr. Francisco Ximénez, O.P. Guatemala: Tipografía Nacional, 1935. Tedlock, Dennis. Popol Vuh: The Mayan Book of the Dawn of Life. Revised ed. New York: Simon, 1996. Woodruff, John M. "Synthesizing Popol Vuh" (dissertation chapter). The "most futile and vain" Work of Father Francisco Ximénez: Rethinking the Context of Popol Vuh. U Alabama. Retrieved 3 Dec 2009. Ximénez, Francisco. Historia de la provincia de San Vicente de Chiapa y Guatemala de la orden de predicadores. Ed. Carmelo Sáenz de Santa María. 2 vols. Mexico: Consejo Estatal para la Cultura y las Artes de Chiapas, 1999. |

参考文献 ロドリゲス・カバル、フアン。『修道院師長兼説教長フランシスコ・ヒメネス師の生涯に関する覚書』グアテマラ:国立印刷所、1935年。 テッドロック、デニス。『ポポル・ヴフ:マヤの生命の夜明けの書』改訂版。ニューヨーク:サイモン社、1996年。 ウッドラフ、ジョン・M. 「ポポル・ヴフの統合」 (学位論文の一章). 『フランシスコ・ヒメネス神父の「最も無益で虚しい」仕事:ポポル・ヴフの文脈を再考する』. アラバマ大学. 2009年12月3日取得. ヒメネス、フランシスコ。『説教者修道会によるサン・ビセンテ・デ・チアパおよびグアテマラ州の歴史』。カルメロ・サエンス・デ・サンタ・マリア編。全2巻。メキシコ:チアパス州文化芸術評議会、1999年。 |

| Other Readings Schumacher, Gudrun; Gregor Wolff (November 2004). Nachlässe, Manuskripte, und Autographen im Besitz des IAI (PDF). Abteilung 2, Referat 1: Nachlässe und Sondersammlungen (in German). Berlin: Ibero-Amerikanisches Institut, Preußischer Kulturbesitz. ISBN 9780520248120. OCLC 162302418. Archived from the original (PDF online document) on 2018-10-08. Retrieved 2008-04-10. |

その他の文献 シューマッハー、グドルン、グレゴール・ヴォルフ(2004年11月)。IAI が所有する遺産、原稿、自筆文書(PDF)。第2部門、第1課:遺産および特別コレクション(ドイツ語)。ベルリン:イベロアメリカ研究所、プロイセン文 化財団。ISBN 9780520248120。OCLC 162302418。2018年10月8日にオリジナル(PDF オンライン文書)からアーカイブ。2008年4月10日に取得。 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Francisco_Xim%C3%A9nez |

Father Ximénez's manuscript contains the oldest known text of Popol Vuh. It is mostly written in parallel K'che' and Spanish as in the front and rear of the first folio pictured here.

Ximénez神父の手稿には、ポポル・ヴフ最古のテキストが含まれている。写真のフォリオ の前後にあるように、ほとんどがK'che'とスペイン語で並行して書かれている。

もくじ

リンク先

文献

その他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆