脱植民地性

Decoloniality,

Decolonialidad

石

油容器を使ったロミュアルド・ハズーメ(Romuald

Hazoumè)のインスタレーション。ハズーメは、「私は西洋に、彼らのもの、つまり、毎日私たちを侵略している消費社会の廃棄物を送る」と

語った。

☆ ★脱植民地性(Decoloniality:decolonialidad) とは、地球上の他の存在形態を可能にするために、ヨーロッパ中心主義的な知識のヒエラルキーや世界におけるあり方から脱却することを目指す学派である。そ れは、西洋の知識の普遍性や西洋文化の優越性、そしてこれらの認識を強化する制度や機関を批判する。脱植民地化の視点では、植民地主義は資本主義的近代性 と帝国主義の日常的な機能の基礎であると理解されている。 デコロニアリティは、南米の運動の一部として、ヨーロッパによるアメリカ大陸の植民地化が、ヨーロッパ中心主義的な近代性/植民地性を確立する上で果たし た役割を検証するものとして登場した。この用語と概念を定義したアニバル・キハーノによると、デコロニアリティ理論と実践は、最近、批判の対象となりつつ ある。

★例えば、オルフェミ・タイウォ(Olúfẹ́mi Táíwò)は、「脱植民地化」は分析上不適切であり、「植民地性」はしばしば「近代性」と混同され、「脱植民地化」は完全な解放という不可能なプロジェ クトになる、と主張している。[6] ヨナタン・クルツウェリ(Jonatan Kurzwelly)とマリン・ヴィケンズ(Malin Wilckens)は、植民地時代に人種差別理論を裏付け、植民地支配の正統性を与えるために収集された人骨の学術コレクションの脱植民地化を例に挙げ、現 代の学術的手法と政治的実践の両方が、アイデンティティの物象化された本質主義的概念を永続させていることを示した。(https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Decoloniality)

++

| Decolonialidad

o

decolonialismo es una escuela de pensamiento que tiene como objetivo

desvincularse de las jerarquías de conocimiento y las formas de estar

en el mundo eurocéntricas y para permitir otras formas de existencia1.

Critica la universalidad percibida del conocimiento occidental y la

superioridad de la cultura occidental, incluidos los sistemas e

instituciones que refuerzan estas percepciones. Las perspectivas

decoloniales entienden al colonialismo como la base de la modernidad

capitalista y el imperialismo. 2 El término decolonialidad surge como parte de un movimiento sudamericano que examina el papel de la colonización europea de las Américas en el establecimiento de la modernidad eurocéntrica. Aníbal Quijano fue quien definió el término y su alcance. Se ha descrito que consiste en "opciones analíticas y prácticas que se enfrentan y se desvinculan de la [...] matriz colonial del poder";3 también ha sido referida como una especie de "pensamiento en la exterioridad radical".4 https://es.wikipedia.org/wiki/Decolonialidad ++++++++++++++++++++++++++++ Decoloniality (Spanish: decolonialidad) is a school of thought that aims to delink from Eurocentric knowledge hierarchies and ways of being in the world in order to enable other forms of existence on Earth.[2] It critiques the perceived universality of Western knowledge and the superiority of Western culture, including the systems and institutions that reinforce these perceptions. Decolonial perspectives understand colonialism as the basis for the everyday function of capitalist modernity and imperialism.[3]: 168-174 Decoloniality emerged as part of a South America movement examining the role of the European colonization of the Americas in establishing Eurocentric modernity/coloniality according to Aníbal Quijano, who defined the term and reach.[2][4][5] Decolonial theory and practice have recently been subject to increasing critique. For example, Olúfẹ́mi Táíwò argued that it is analytically unsound, that "coloniality" is often conflated with "modernity", and that "decolonisation" becomes an impossible project of total emancipation.[6] Jonatan Kurzwelly and Malin Wilckens used the example of decolonisation of academic collections of human remains, which were collected during colonial times to support racist theories and give legitimacy to colonial oppression, and showed how both contemporary scholarly methods and political practice perpetuate reified and essentialist notions of identities.[7] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Decoloniality |

脱植民地性(decoloniality)また

は脱植民地主義(decolonialism)とは、ヨーロッパ中心主義的な知識や世界における存在のあり方のヒエラルキーから離脱し、他の形態の存在を

認めることを目指す思想の学派である1。脱植民地主義とは、西洋の知識の普遍性や西洋文化の優位性を批判するものであり、こうした認識を強化するシステム

や制度も含まれる。脱植民地主義の視点は、植民地主義を資本主義的近代性と帝国主義の基礎として理解している。2 脱植民地性(decoloniality)という言葉は、ヨーロッパ中心主義的な近代性の確立において、ヨーロッパによるアメリカ大陸の植民地化が果たし た役割を検証する南米の運動の一環として生まれた。この用語とその範囲は、アニバル・キハノによって定義された。植民地主義とは、「植民地的な権力のマト リックスに立ち向かい、そこから自らを切り離すための分析的で実践的な選択肢」3からなるものであり、一種の「急進的な外部性の思考」とも呼ばれている 4。 +++++++++++++++++++++++ 脱植民地性(スペイン語: decolonialidad)とは、地球上で他の存在形態を可能にするため、ヨーロッパ中心の知識階層や世界との関わり方から切り離すことを目指す思想 潮流である[2]。西洋知識の普遍性や西洋文化の優越性、そしてこうした認識を強化する制度や機構を批判する。脱植民地化の視点では、植民地主義が資本主 義的近代性と帝国主義の日常的機能の基盤であると理解される。[3]: 168-174 脱植民地性は、アニバル・キハノが用語と範囲を定義したように、南米運動の一部として出現した。この運動は、ヨーロッパによるアメリカ大陸の植民地化が、ヨーロッパ中心の近代性/植民地性を確立する上で果たした役割を検証するものである。[2][4] [5] 脱植民地化理論と実践は近年、批判が高まっている。例えばオルフェミ・タイウォは、その分析的根拠が不十分であり、「植民地性」がしばしば「近代性」と混 同され、「脱植民地化」が完全な解放という不可能なプロジェクトに陥ると論じた。[6] ヨナタン・クルツヴェリーとマリン・ヴィルケンスは、人種差別的理論を支持し植民地支配の正当化に利用された植民地時代に収集された学術的人体標本の脱植民地化を例に挙げ、現代の学術的方法と政治的実践の双方が、物象化された本質主義的なアイデンティティ観念を永続化させていることを示した。[7] |

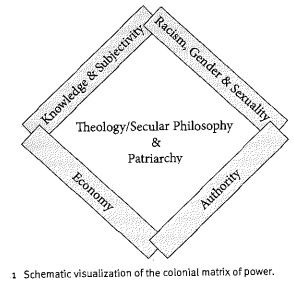

| Matriz colonial del poder Como tal, puede contrastarse con la colonialidad que es "la lógica subyacente de la fundación y despliegue de la civilización occidental desde el Renacimiento hasta hoy",3 una lógica que fue la base de los colonialismos históricos, aunque esta interconexión fundamental a menudo se minimiza. Esta lógica se conoce comúnmente como la matriz colonial del poder o la colonialidad del poder. Aunque la colonización formal y explícita terminó con la descolonización de América durante el siglo xix y la descolonización de gran parte del sur global a fines del siglo xx, sus sucesores, el imperialismo occidental y la globalización perpetúan esas desigualdades. La matriz colonial del poder produjo una discriminación social eventualmente codificada como "racial", "étnica", "antropológica" o "nacional" según contextos históricos, sociales y geográficos específicos.5 La descolonialidad surgió en el momento en que la matriz colonial del poder se puso en marcha durante el siglo xvi. Es, en efecto, una confrontación continua y una desvinculación del eurocentrismo: la idea de que la historia de la civilización humana ha sido una trayectoria que se apartó de la naturaleza y culminó en Europa, también que las diferencias entre Europa y fuera de Europa se deben a diferencias biológicas entre razas, no historias de poder.6 La decolonialidad es sinónimo de "pensar y hacer" decolonialmente3 y cuestiona o problematiza las historias de poder que emergen de Europa. Estas historias subyacen a la lógica de la civilización occidental. La decolonialidad es una respuesta a la relación de dominación directa, política, social y cultural establecida por los europeos.5 Esto significa que la decolonialidad se refiere a enfoques analíticos y prácticas socioeconómicas y políticas opuestas a los pilares de la civilización occidental: la colonialidad y la modernidad. Esto hace que la decolonialidad sea un proyecto tanto político como epistémico.3 La decolonialidad ha sido llamada una forma de "desobediencia epistémica",7 "desvinculación epistémica"8 y "reconstrucción epistémica".5 En este sentido, el pensamiento decolonial es el reconocimiento y la implementación de una gnosis fronteriza o razón subalterna,9 un medio para eliminar la tendencia provinciana de pretender que los modos de pensar de Europa occidental son de hecho universales.6 En sus aplicaciones menos teóricas y más prácticas, como los movimientos por la autonomía indígena, como el autogobierno zapatista, la decolonialidad se llama a una "programática" de desvinculación de los legados contemporáneos de la colonialidad,8 una respuesta a las necesidades no resueltas por los gobiernos derechistas o izquierdistas modernos, o, más ampliamente, los movimientos sociales en busca de una "nueva humanidad"3 o la búsqueda de "liberación social de todo poder organizado como desigualdad, discriminación, explotación y dominación".5 |

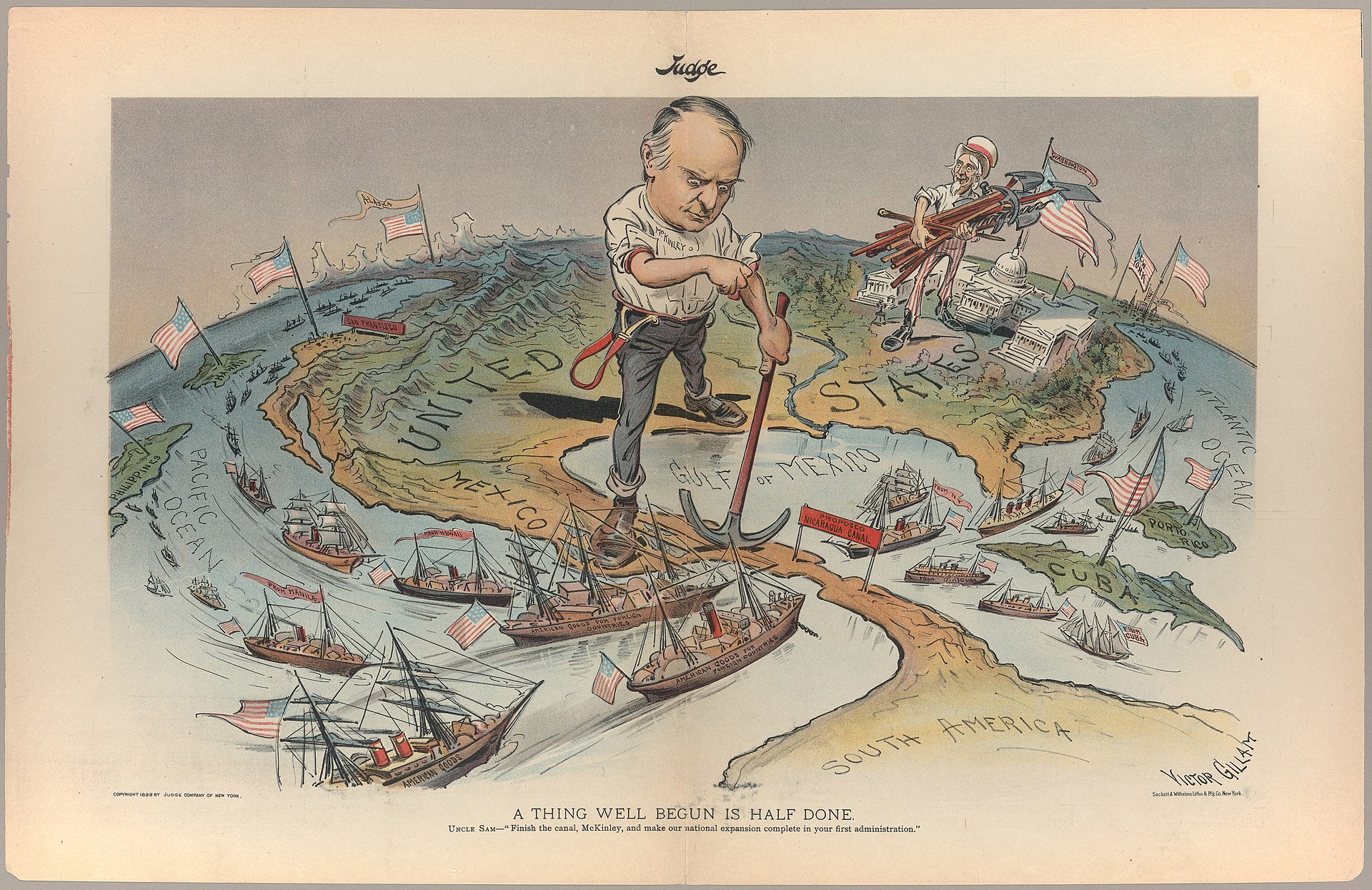

権力の植民地的マトリックス ルネサンス期から今日に至るまで、「西洋文明の成立と展開の根底にある論理」3である植民地性と対比されることがあるが、この基本的な相互関連性は軽視され がちである。この論理は一般に、権力の植民地的マトリックス、あるいは権力の植民地性と呼ばれている。 19世紀にアメリカ大陸が脱植民地化され、20世紀後半にはグローバル・サウスの大部分が脱植民地化されたことで、公式かつ明確な植民地化は終わったが、 その後継者である西洋帝国主義とグローバリゼーションは、こうした不平等を永続させている。権力の植民地的マトリックスは、特定の歴史的、社会的、地理的 文脈に従って、最終的に「人種的」、「民族的」、「人類学的」、あるいは「国民的」として体系化された社会的差別を生み出した5。それは事実上、ヨーロッ パ中心主義との継続的な対決であり、そこからの離脱である。つまり、人類の文明の歴史は自然から出発し、ヨーロッパに至った軌跡であり、ヨーロッパとヨー ロッパ外の違いは人種間の生物学的な違いによるものであり、権力の歴史ではないという考え方である6。 脱植民地主義は、脱植民地的な「思考と行動」3と同義であり、ヨーロッパから生まれた権力の歴史に疑問を投げかけ、問題化する。これらの歴史は西洋文明の 論理の根底にある。脱植民地主義とは、ヨーロッパ人によって確立された直接的な政治的、社会的、社会的、文化的支配の関係に対する反応である5。つまり、 脱植民地主義とは、西洋文明の柱である植民地性と近代性に対立する分析的アプローチや社会経済的、政治的実践を指す。このことは、脱植民地主義を認識論的 プロジェクトであると同時に政治的プロジェクトとしている3。 脱植民地主義は、「認識論的不服従」7、「認識論的離反」8、「認識論的再構築」5と呼ばれてきた。この意味で、脱植民地主義的思考とは、境界のグノーシ ス、あるいはサブアルタン的理性9を認識し、実行することであり、西欧的思考様式が実際には普遍的であるかのように装う田舎者的傾向を排除する手段である 6。 サパティスタ自治のような先住民の自治運動など、理論的でなく、より実践的な応用において、脱植民地主義は、植民地性の現代的遺産からの「プログラム的 な」離脱8、現代の右翼または左翼政府によって満たされないニーズへの対応、あるいはより広義には、「新しい人間性」3、あるいは「不平等、差別、搾取、 支配として組織されたあらゆる権力からの社会的解放」の探求を求める社会運動と呼ばれている5。 |

| Desambiguaciones La decolonialidad a menudo se mezcla con el poscolonialismo, la descolonización, la colonialidad y el posmodernismo. Sin embargo, los teóricos decoloniales se distinguen de tales términos. Poscolonialismo El poscolonialismo a menudo se incorpora a las prácticas generales de oposición por parte de "personas de color", "intelectuales del Tercer Mundo" o "grupos étnicos" (Mignolo 2000: 87). Se dice que la decolonialidad, tanto analítica como programática, se mueve "más allá de lo poscolonial" porque "la teoría y la crítica poscolonial es un proyecto de transformación académica dentro de la academia".8 Descolonización La descolonización es en gran parte política e histórica: el final del período de dominación territorial de las tierras, principalmente en el sur global por las potencias europeas. La colonialidad es, de hecho, la sustancia del período histórico de la colonización: sus construcciones sociales, imaginarios, prácticas, jerarquías y violencia. Esta sustancia se manifestó en todo el mundo y determinó los sistemas de valores socioeconómicos, raciales y epistemológicos de la sociedad contemporánea, comúnmente llamada sociedad "moderna". La colonialidad no desapareció con la descolonización: el fin del siglo xix de la dominación territorial de las Américas por parte de las naciones ibéricas, o el final del siglo xx de la dominación territorial de Asia y África por parte de otras naciones europeas. Colonialidad La colonialidad como concepto es complementaria a la modernidad y se llama "el lado más oscuro de la modernidad occidental".3 Los aspectos problemáticos de la colonialidad –el racismo, el sexismo, el ecocidio, el etnocidio y el genocidio– a menudo se pasan por alto al describir la totalidad de la sociedad occidental. Posmodernidad El advenimiento de la sociedad occidental en cambio se discute a menudo como la introducción de la modernidad y la racionalidad, un concepto criticado por los pensadores posmodernos. Sin embargo, esta crítica es en gran medida "limitada e interna a la historia europea y la historia de las ideas europeas".8 Aunque los pensadores posmodernos reconocen la naturaleza problemática de las nociones de modernidad y racionalidad, estos pensadores a menudo pasan por alto el hecho de que la modernidad como concepto surgió cuando Europa se definió a sí misma como el "centro" del mundo. Esto significa que pasan por alto el hecho de que aquellos definidos como "periferia" son parte de la autodefinición de Europa. En pocas palabras, al igual que la modernidad, la posmodernidad a menudo reproduce la "falacia eurocéntrica" fundamental para la modernidad. Por lo tanto, en lugar de criticar los terrores de la modernidad, el pensamiento y el hacer decoloniales critican la modernidad y la racionalidad eurocéntricas debido al "mito irracional" que ocultan.8 De este modo, los enfoques decoloniales buscan "politizar la epistemología a partir de las experiencias de aquellos en la 'frontera', no desarrollar otra epistemología de la política".10 |

曖昧さの解消 脱植民地主義はしばしばポストコロニアリズム、脱植民地化、植民地主義、ポストモダニズムと混同される。しかし、脱植民地主義の理論家たちは、このような 用語とは一線を画している。 ポストコロニアリズム(→ポストコロニアリティ) ポストコロニアリズムは、「有色人種」、「第三世界の知識人」、「エスニック・グループ」による一般的な反対実践にしばしば組み込まれている (Mignolo 2000: 87)。脱植民地主義は、分析的にもプログラム的にも、「ポストコロニアルを超える」ものであると言われている。なぜなら、「ポストコロニアルの理論と批 評は、アカデミズムにおける学問的変革のプロジェクト」だからである8。 脱植民地化 脱植民地化とは、主に政治的・歴史的なものであり、主にヨーロッパ列強による南半球の土地の領土支配が終わることである。植民地性とは、事実、植民地化の 歴史的期間の実体であり、その社会的構築、想像力、実践、階層、暴力である。この物質は世界的に顕在化し、一般に「近代」社会と呼ばれる現代社会の社会経 済的、人種的、認識論的価値体系を決定づけた。19世紀のイベリア諸国によるアメリカ大陸の領土支配の終焉や、20世紀のヨーロッパ諸国によるアジアやア フリカの領土支配の終焉など、脱植民地化によっても植民地主義は消滅しなかった。 植民地性 植民地主義という概念は、近代性を補完するものであり、「西洋近代の暗黒面」と呼ばれている3。植民地主義の問題点である人種差別、性差別、エコサイド、 エスノサイド、ジェノサイドは、西洋社会の全体像を語る上で見過ごされがちである。 ポストモダン 西洋社会の到来は、近代性と合理性の導入として語られることが多いが、この概念はポストモダンの思想家たちによって批判されている。ポストモダンの思想家 たちは、近代性や合理性という概念の問題性を認めながらも、近代性という概念が、ヨーロッパが自らを世界の「中心」と定義したときに出現したという事実を しばしば見落としている。つまり、「周縁」と定義されたものがヨーロッパの自己定義の一部であるという事実を見落としているのである。要するに、モダニ ティと同様、ポストモダニティもモダニティの基本である「ヨーロッパ中心主義の誤謬」をしばしば再生産しているのである。このように、脱植民地的な思考と 行動は、近代の恐ろしさを批判するのではなく、それらが隠蔽する「非合理的な神話」のゆえに、ヨーロッパ中心主義的な近代と合理性を批判するのである8。 このように、脱植民地的なアプローチは、「政治に関する別の認識論を発展させるのではなく、『辺境』にいる人々の経験から認識論を政治化」しようとする。 |

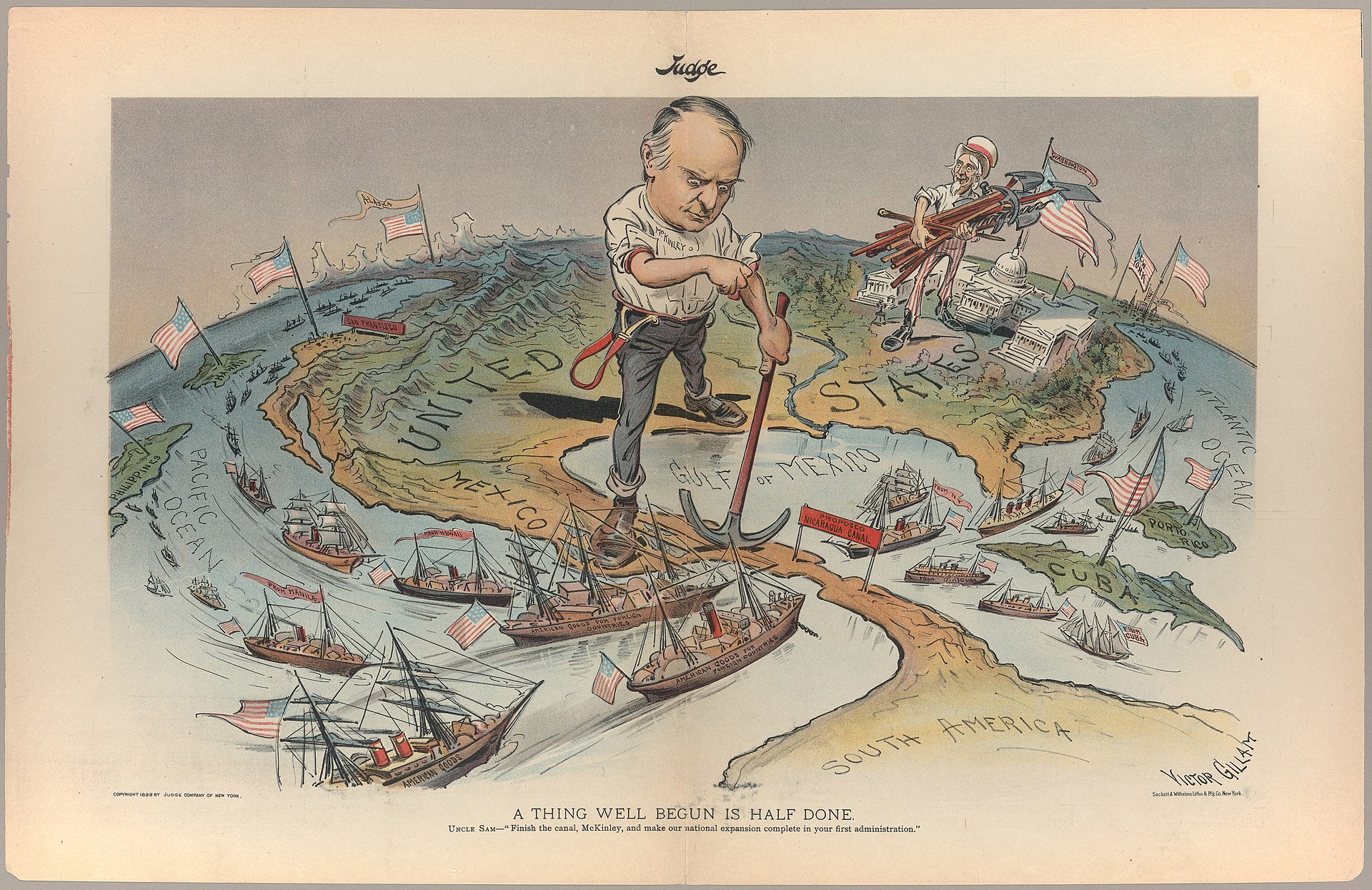

| Decolonialidad contemporánea Es crítico reconocer que la "estructura del poder fue e incluso continúa siendo organizada en y alrededor del eje colonial",6 que la descolonización no eliminó la colonialidad, "simplemente transformó su forma externa".11 Los elevados objetivos de la decolonialidad, tanto en su función analítica como programática, son expresados sucintamente por Aníbal Quijano: reconocer que la instrumentalización de la razón por la matriz colonial del poder produjo paradigmas de conocimiento distorsionados y echó a perder las promesas liberadoras de la modernidad y, por ese reconocimiento, darse cuenta de la destrucción de la colonialidad global del poder.8 Ejemplos de programas y análisis arquitectónicos decoloniales contemporáneos existen en todas las Américas. La programática decolonial incluye los ya mencionados gobernantes zapatistas del sur de México, movimientos indígenas para la autonomía en toda América del Sur, incluyendo CONFENIAE en Ecuador, ONIC en Colombia, el movimiento TIPNIS en Bolivia y el Movimiento de Trabajadores Sin Tierra (MST) en Brasil. La reciente organización transnacional de una coalición de pueblos indígenas en la forma del movimiento Idle No More es otro ejemplo más de la programática decolonial. Estos movimientos encarnan una acción orientada hacia los objetivos expresados en la declaración anterior de Quijano, sucintamente, para buscar libertades cada vez mayores, desafiando el razonamiento detrás de la modernidad, ya que la modernidad es de hecho una faceta de la matriz colonial de poder. |

現代の脱植民地主義 脱植民地化は植民地性を排除したのではなく、「その外形的な形を変えただけ」である。 11 脱植民地主義の高邁な目標は、その分析的機能においてもプログラム的機能においても、アニバル・キハーノによって簡潔に表現されている。 現代の脱植民地的建築プログラムと分析の例は、アメリカ大陸各地に存在する。脱植民地的プログラムには、前述のメキシコ南部のサパティスタ支配者、エクア ドルのCONFENIAE、コロンビアのONIC、ボリビアのTIPNIS運動、ブラジルの土地なし労働者運動(MST)など、南米各地の先住民の自治運 動が含まれる。最近、アイドル・ノー・モア運動という形で先住民の連合が国境を越えて組織化されたが、これも脱植民地主義的なプログラムの一例である。こ れらの運動は、キハノが先に述べたように、より大きな自由を求め、近代性の背後にある理性に挑戦し、近代性は実際には植民地的な権力マトリックスの一面で あるとして、より大きな自由を求めるという目標を志向する行動を体現している。 |

| Aníbal Quijano Descolonización Posmodernismo Poscolonialismo Walter Mignolo Enrique Dussel |

アニバル・キハノ 脱植民地化 ポストモダニズム ポストコロニアリズム ウォルター・ミニョロ エンリケ・ドゥッセル |

| https://es.wikipedia.org/wiki/Decolonialidad 脱植民地批判(Decolonial critique) |

研究者、著者、クリエイター、理論家、その他の人々は、エッセイ、アー トワーク、メディアを通じて脱植民地化に取り組んでいる。これらのクリエイターの多 くは脱植民地化批評に取り組んでいる。脱植民地化批評では、思想家は脱植民地化によって進められた理論的、政治的、認識論的、社会的枠組みを用いて、広く 受け入れられ賞賛されている概念を精査し、再定式化し、自然化を否定する。多くの脱植民地的批判は、植民地および人種的枠組みの中で位置づけられる近代性 の概念の再構築に焦点を当てている。脱植民地的批判は、西洋の階層構造の再生産から脱却する脱植民地的文化を鼓舞する可能性がある。脱植民地的批判は、脱 植民地的方法と実践を認識論、社会、政治的思考のあらゆる側面に適用する方法である。 |

| 【再掲】 Decoloniality (Spanish: decolonialidad) is a school of thought that aims to delink from Eurocentric knowledge hierarchies and ways of being in the world in order to enable other forms of existence on Earth.[2] It critiques the perceived universality of Western knowledge and the superiority of Western culture, including the systems and institutions that reinforce these perceptions. Decolonial perspectives understand colonialism as the basis for the everyday function of capitalist modernity and imperialism.[3]: 168-174 Decoloniality emerged as part of a South America movement examining the role of the European colonization of the Americas in establishing Eurocentric modernity/coloniality according to Aníbal Quijano, who defined the term and reach.[2][4][5] Decolonial theory and practice have recently been subject to increasing critique. For example, Olúfẹ́mi Táíwò argued that it is analytically unsound, that "coloniality" is often conflated with "modernity", and that "decolonisation" becomes an impossible project of total emancipation.[6] Jonatan Kurzwelly and Malin Wilckens used the example of decolonisation of academic collections of human remains, which were collected during colonial times to support racist theories and give legitimacy to colonial oppression, and showed how both contemporary scholarly methods and political practice perpetuate reified and essentialist notions of identities.[7] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Decoloniality |

【再掲】 脱植民地性(スペイン語: decolonialidad)とは、地球上で他の存在形態を可能にするため、ヨーロッパ中心の知識階層や世界との関わり方から切り離すことを目指す思想 潮流である[2]。西洋知識の普遍性や西洋文化の優越性、そしてこうした認識を強化する制度や機構を批判する。脱植民地化の視点では、植民地主義が資本主 義的近代性と帝国主義の日常的機能の基盤であると理解される。[3]: 168-174 脱植民地性は、アニバル・キハノが用語と範囲を定義したように、南米運動の一部として出現した。この運動は、ヨーロッパによるアメリカ大陸の植民地化が、ヨーロッパ中心の近代性/植民地性を確立する上で果たした役割を検証するものである。[2][4] [5] 脱植民地化理論と実践は近年、批判が高まっている。例えばオルフェミ・タイウォは、その分析的根拠が不十分であり、「植民地性」がしばしば「近代性」と混 同され、「脱植民地化」が完全な解放という不可能なプロジェクトに陥ると論じた。[6] ヨナタン・クルツヴェリーとマリン・ヴィルケンスは、人種差別的理論を支持し植民地支配の正当化に利用された植民地時代に収集された学術的人体標本の脱植 民地化を例に挙げ、現代の学術的方法と政治的実践の双方が、物象化された本質主義的なアイデンティティ観念を永続化させていることを示した。[7] |

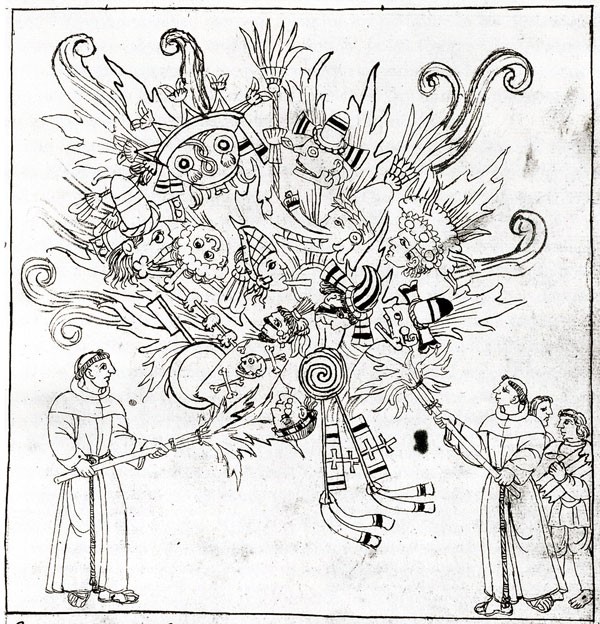

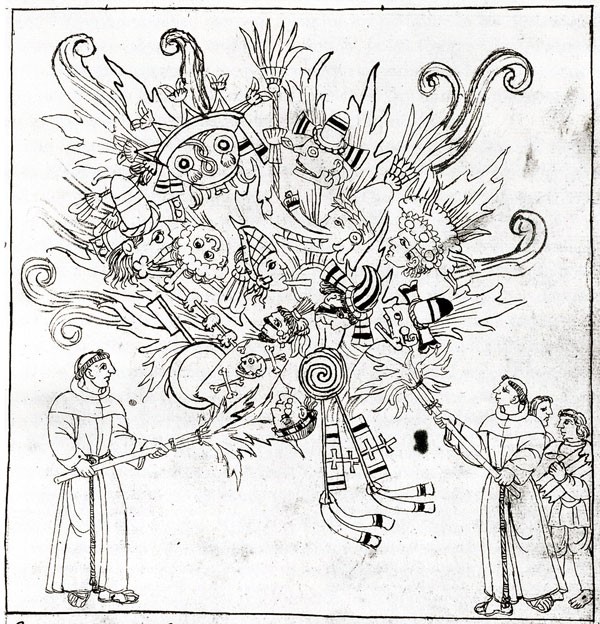

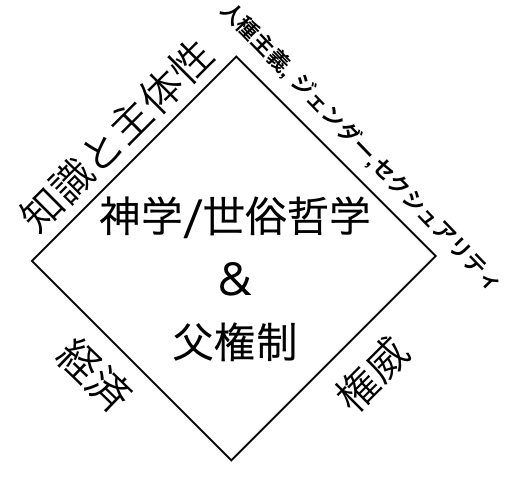

| Foundational principles Coloniality of knowledge This section is an excerpt from Coloniality of knowledge.[edit]  In his 1585 Descripción de Tlaxcala, Diego Muñoz Camargo illustrated the book burning of pre-Columbian codices by Franciscan friars.[8] Coloniality of knowledge is a concept that Peruvian sociologist Anibal Quijano developed and adapted to contemporary decolonial thinking. The concept critiques what proponents call the Eurocentric system of knowledge, arguing the legacy of colonialism survives within the domains of knowledge. For decolonial scholars, the coloniality of knowledge is central to the functioning of the coloniality of power and is responsible for turning colonial subjects into victims of the coloniality of being, a term that refers to the lived experiences of colonized peoples. Coloniality of power This section is an excerpt from Coloniality of power.[edit] The coloniality of power is a concept interrelating the practices and legacies of European colonialism in social orders and forms of knowledge, advanced in postcolonial studies, decoloniality, and Latin American subaltern studies, most prominently by Anibal Quijano. It identifies and describes the living legacy of colonialism in contemporary societies in the form of social discrimination that outlived formal colonialism and became integrated in succeeding social orders.[9] The concept identifies the racial, political and social hierarchical orders imposed by European colonialism in Latin America that prescribed value to certain peoples/societies while disenfranchising others. Colonialism as the root  Decoloniality is founded on the principle that European colonialism is at the root of how the modern world functions today.[10][11] The decolonial movement includes diverse forms of critical theory, articulated by pluriversal forms of liberatory thinking that arise out of distinct situations. In its academic forms, it analyzes class distinctions, ethnic studies, gender studies, and area studies. It has been described as consisting of analytic (in the sense of semiotics) and practical “options confronting and delinking from [...] the colonial matrix of power"[12]: xxvii or from a "matrix of modernity" rooted in colonialism.[10][11]  It considers colonialism "the underlying logic of the foundation and unfolding of Western civilization from the Renaissance to today," although this foundational interconnectedness is often downplayed.[12]: 2 This logic is commonly referred to as the colonial matrix of power or coloniality of power. Some have built upon decolonial theory by proposing Critical Indigenous Methodologies for research.[13] Imperialism as the successor  Decoloniality sees imperialism as a perpetuation of inequalities initiated by Western colonialism.[3]: 168 Although formal and explicit colonization ended with the decolonization of the Americas during the eighteenth and nineteenth century and the decolonization of much of the Global South in the late twentieth century, its successors, Western imperialism and globalization perpetuate those inequalities. The colonial matrix of power produced social discrimination eventually variously codified as racial, ethnic, anthropological or national according to specific historic, social, and geographic contexts.[3]: 168 Decoloniality emerged as the colonial matrix of power was put into place during the 16th century.[citation needed][clarification needed] It is, in effect, a continuing confrontation of, and delinking from, Eurocentrism.[14]: 542 Coloniality of gender This section is an excerpt from Coloniality of gender.[edit]  March against femicide at UNAM in 2017. The coloniality of gender has been used to explain how modern femicide is tied to the European colonization of the Americas.[15] Coloniality of gender is a concept developed by Argentine philosopher Maria Lugones. Building off Aníbal Quijano's foundational concept of coloniality of power,[16] coloniality of gender explores how European colonialism influenced and imposed European gender structures on Indigenous peoples of the Americas. This concept challenges the notion that gender can be isolated from the impacts of colonialism. Scholars have also extended the concept of coloniality of gender to describe colonial experiences in Asian and African societies. The concept is notably employed in academic fields like decolonial feminism and the broader study of decoloniality.[17] Disobedience and de-linking Decoloniality has been called a form of "epistemic disobedience",[12]: 122-123 "epistemic de-linking",[18]: 450 and "epistemic reconstruction".[3]: 176 In this sense, decolonial thinking is the recognition and implementation of a border gnosis or subaltern,[19]: 88 a means of eliminating the provincial tendency to pretend that Western European modes of thinking are universal.[14]: 544 In less theoretical applications—such as movements for Indigenous autonomy—decoloniality is considered a program of de-linking from contemporary legacies of coloniality,[18]: 452 a response to needs unmet by the modern Rightist or Leftist governments,[12]: 217 or, most broadly, social movements in search of a “new humanity”[12]: 52 or the search for “social liberation from all power organized as inequality, discrimination, exploitation, and domination”.[3]: 178 Decoloniality Frantz Fanon and Aimé Césaire contributed to decolonial thinking, theory, and practice by identifying core principles of decoloniality. The first principle they identified is that colonialism must be confronted and treated as a discourse which fundamentally frames all aspects of thinking, organization, and existence. Framing colonialism as a "fundamental problem" empowers the colonized to center their experiences and thinking without seeking the recognition of the colonizer—a step towards the creation of decolonial thinking.[20] The second core principle is that decolonization goes beyond ending colonization. Nelson Maldonado-Torres explains, "For decolonial thinking decolonization is less the end of colonialism wherever it has occurred and more the project of undoing and unlearning the coloniality of power, knowledge, and being and of creating a new sense of humanity and forms of interrelationality."[20] This is the work of the decolonial project that has epistemic, political, and ethical dimensions.[21] Aníbal Quijano summarized the goals of decoloniality as a need to recognize that the instrumentation of reason by the colonial matrix of power produced distorted paradigms of knowledge and spoiled the liberating promises of modernity, and by that recognition, realize the destruction of the global coloniality of power.[18]: 452 Alanna Lockward explains that Europe has engaged in an intentional "politics of confusion" to conceal the relationship between modernity and coloniality.[22] Decoloniality is synonymous with decolonial "thinking and doing",[12]: xxiv and it questions or problematizes the histories of power emerging from Europe. These histories underlie the logic of Western civilization.[3]: 168 Thus, decoloniality refers to analytic approaches and socioeconomic and political practices opposed to pillars of Western civilization: coloniality and modernity. This makes decoloniality both a political and epistemic project.[12]: xxiv-xxiv Examples Examples of contemporary decolonial programmatics and analytics exist throughout the Americas. Decolonial movements include the contemporary Zapatista governments of Southern Mexico, Indigenous movements for autonomy throughout South America, ALBA,[23] CONFENIAE in Ecuador, ONIC in Colombia, the TIPNIS movement in Bolivia, and the Landless Workers' Movement in Brazil. These movements embody action oriented towards the goals expressed to seek ever-increasing freedoms by challenging the reasoning behind modernity, since modernity is in fact a facet of the colonial matrix of power.[citation needed] Examples of contemporary decolonial analytics include ethnic studies programs at various educational levels designed primarily to appeal to certain ethnic groups, including those at the K-12 level recently banned in Arizona, as well as long-established university programs. Scholars primarily with analytics who fail to recognize the connection between politics or decoloniality and the production of knowledge—between programmatics and analytics—are those claimed by decolonialists to most likely to reflect "an underlying acceptance of capitalist modernity, liberal democracy, and individualism" values which decoloniality seeks to challenge.[24]: 6 |

基礎的な原則 知識の植民地性(→「知識の脱植民地化」) このセクションは、知識の植民地性からの抜粋である。[編集]  1585年の『トラスカラの記述』の中で、ディエゴ・ムニョス・デ・カマルゴは、フランシスコ会の修道士によるコロンブス到来以前の時代のコデックス(写本)の焼却を例示した。[8] 知識の植民地性とは、ペルーの社会学者アニバル・キホーノが開発し、脱植民地的な思考に適応させた概念である。この概念は、知識の欧州中心主義システムを 批判し、知識の領域内に植民地主義の遺産が生き残っていると主張する。脱植民地化の学者にとって、知識の植民地性は権力の植民地性の機能の中心であり、植 民地化された人々の生活体験を指す「植民地化された存在」という用語で、植民地化された人々を植民地性の犠牲者に変える原因である。 権力の植民地性 このセクションは、権力の植民地性からの抜粋である。 権力の植民地性とは、ポストコロニアル研究、脱植民地化、ラテンアメリカ・サバルタン研究(特にアニバル・キハノによる)で発展した、社会秩序と知識の 形態におけるヨーロッパの植民地主義の実践と遺産を相互に関連付ける概念である。それは、現代社会における植民地主義の生き残った遺産を、形式的な植民地 主義が終焉を迎えた後も存続し、後続の社会秩序に統合された社会差別の形態として特定し、記述するものである。[9] この概念は、ヨーロッパの植民地主義がラテンアメリカに課した人種的、政治的、社会的階層秩序を特定し、特定の人々や社会に価値を規定する一方で、他の人 々を排除した。 植民地主義を根源とする  脱植民地化は、ヨーロッパの植民地主義が現代世界の機能の根底にあるという原則に基づいている。[10][11] 脱 植民地化運動は、多様な批判理論を含む。それは、異なる状況から生じる解放的思考の多元的な形態によって表現される。学術的な形態においては、階級区分、 民族研究、ジェンダー研究、地域研究を分析する。それは(記号論的な意味での)分析的かつ実践的な「植民地的な権力マトリックス」[12]:xxvii あるいは植民地主義に根ざした「近代性のマトリックス」[10][11] に対峙し、そこから切り離す「選択肢」から成ると説明されている。  植民地主義は「ルネサンスから今日に至る西洋文明の基礎と展開の根底にある論理」であると考えるが、この基礎的な相互関連性はしばしば軽視されている。 [12]: 2 この論理は一般的に、植民地的な権力の基盤または権力の植民地性と呼ばれている。 研究のための批判的土着的方法論を提案することで、脱植民地理論を基盤とするものもある。[13] 帝国主義は後継者である  脱植民地化論は、帝国主義を西洋の植民地主義によって始まった不平等が永続しているものと見なしている。[3]: 168 公式かつ明白な植民地化は、18世紀から19世紀にかけてのアメリカ大陸の脱植民地化と、20世紀後半におけるグローバル・サウスの大部分の脱植民地化に よって終結したが、その継承者である西洋の帝国主義とグローバリゼーションは、それらの不平等を永続させている。植民地主義的な権力の構造は、特定の歴史 的、社会的、地理的文脈に応じて、最終的に人種的、民族的、人類学的、あるいは国家的としてさまざまな形で法制度化された社会差別を生み出した。[3]: 168 脱植民地性は、16世紀に植民地主義的な権力の構造が確立された際に登場した。[要出典][要説明] 実質的には、脱植民地性は、ユーロセントリズムとの継続的な対立であり、ユーロセントリズムからの脱却である。[14]: 542 ジェンダーの植民地性 このセクションは、ジェンダーの植民地性からの抜粋である。  2017年のUNAMにおけるフェミサイド反対デモ。ジェンダーの植民地性は、近代のフェミサイドがヨーロッパによるアメリカ大陸の植民地化とどのように 結びついているかを説明するのに用いられてきた。 ジェンダーの植民地性は、アルゼンチンの哲学者マリア・ルゴネスが開発した概念である。アニバル・キハノの「権力の植民地性」の基礎概念を基に構築された ジェンダーの植民地性は、ヨーロッパの植民地主義がアメリカ大陸の先住民にヨーロッパのジェンダー構造をどのように影響させ、押し付けたかを探究する。こ の概念は、ジェンダーが植民地主義の影響から切り離されるという考えに異議を唱えるものである。 学者たちはジェンダーの植民地性という概念をさらに発展させ、アジアやアフリカの社会における植民地体験を説明するのに用いている。この概念は、脱植民地 フェミニズムや脱植民地性のより広範な研究といった学術分野で特に用いられている。 不服従と脱連結 脱植民地性は、「認識的不服従」の一形態であると称され[12]: 122-123、「認識的脱連結」[18]: 450、「認識的再構築」[3]: 176である。この意味において、脱植民地的な思考とは、 ボーダー・グノーシスまたはサバルタン[19]の認識と実践であり、西ヨーロッパの思考様式が普遍的であるかのように装う地方的な傾向を排除する手段であ る[14] 52 現代の右派または左派政権が満たしていないニーズへの対応[12]: 217、または最も広く言えば、「新しい人間性」[12]: 52、あるいは「不平等、差別、搾取、支配として組織化されたあらゆる権力からの社会的解放」[3]: 178の追求としての社会運動である。 脱植民地性 フランツ・ファノンとエメ・セゼールは、脱植民地性の主要原則を特定することで、脱植民地主義的な思考、理論、実践に貢献した。彼らが最初に特定した原則 は、植民地主義は思考、組織、存在のあらゆる側面を根本的に形作る言説として対峙し、扱われなければならないというものである。植民地主義を「根本的な問 題」として捉えることで、植民地化された人々は、植民地主義者の承認を求めずに、自らの経験や思考を重視することが可能になる。これは脱植民地主義的な思 考の創造に向けた一歩である。[20] 2つ目の主要原則は、脱植民地化は植民地主義の終結を越えるものであるというものである。ネルソン・マルドナド=トーレスは次のように説明している。「脱 植民地化とは、脱植民地化が起こった場所における植民地主義の終結というよりも、権力、知識、存在の植民地性を覆し、それを学ばないようにするプロジェク トであり、新たな人間性と相互関係性の形態を創造するプロジェクトである」[20] これは、認識論的、政治的、倫理的な側面を持つ脱植民地化プロジェクトの作業である。[21] アニバル・キハノは脱植民地化の目標を、植民地主義的な権力のマトリックスによる理性の道具化が歪んだ知識のパラダイムを生み出し、近代の解放的な約束を 台無しにしたことを認識する必要性であり、その認識によって、 グローバルな権力の植民地性を破壊することに気づく必要があると主張している。[18]: 452 アラーナ・ロックワードは、ヨーロッパが近代性と植民地性の関係を隠蔽するために意図的な「混乱の政治」を行ってきたと説明している。[22] 脱植民地性は脱植民地的な「思考と実践」と同義であり[12]: xxiv、ヨーロッパから生じた権力の歴史を問い質すものである。これらの歴史は西洋文明の論理の根底にある[3]: 168。したがって、脱植民地性とは西洋文明の柱である植民地性と近代性に対抗する分析的アプローチと社会経済的・政治的実践を指す。このため、脱植民地 化は政治的かつ認識論的なプロジェクトである。[12]: xxiv-xxiv 例 現代の脱植民地化のプログラムや分析の例は、南北アメリカ大陸全体に存在する。脱植民地化運動には、南メキシコのサパティスタ政府、南米全域の自治を求め る先住民運動、ベネズエラとコロンビアの南米諸国による同盟(ALBA)[23]、エクアドルのCONFENIAE、コロンビアのONIC、ボリビアの ティピサニ運動、ブラジルの土地なし労働者運動などがある。これらの運動は、近代性の背後にある論理に異議を唱えることで、増大し続ける自由を求めるとい う目標に向けられた行動を体現している。なぜなら、近代性は実際には権力の植民地的な基盤の側面であるからだ。 現代の脱植民地化分析の例としては、主に特定の民族グループに訴えることを目的とした、さまざまな教育レベルにおける民族研究プログラムがある。これに は、最近アリゾナ州で禁止された幼稚園から高校3年生までのレベルのプログラムや、長年にわたって確立された大学のプログラムも含まれる。主に分析学を専 門とする学者で、政治や脱植民地性と知識の生産との関係、すなわちプログラムと分析学との関係を認識していない者は、脱植民地主義者たちから、脱植民地性 が挑戦しようとしている「資本主義的近代、自由民主主義、個人主義」の価値観を根底から受け入れている可能性が高いと主張されている。[24]: 6 |

| Decolonial critique |

→「脱植民地批判」 |

| Distinction from related ideas Decoloniality is often conflated with postcolonialism, decolonization, and postmodernism. However, decolonial theorists draw clear distinctions. Postcolonialism Postcolonialism is often mainstreamed into general oppositional practices by "people of color", "Third World intellectuals", or ethnic groups.[19]: 87 Decoloniality—as both an analytic and a programmatic approach—is said to move "away and beyond the post-colonial" because "post-colonialism criticism and theory is a project of scholarly transformation within the academy".[18]: 452 This final point is debatable, as some postcolonial scholars consider postcolonial criticism and theory to be both an analytic (a scholarly, theoretical, and epistemic) project and a programmatic (a practical, political) stance.[36]: 8 This disagreement is an example of the ambiguity—"sometimes dangerous, sometimes confusing, and generally limited and unconsciously employed"—of the term "postcolonialism," which has been applied to analysis of colonial expansion and decolonization, in contexts such as Algeria, the 19th-century United States, and 19th-century Brazil.[37]: 93-94 Decolonial scholars consider the colonization of the Americas a precondition for postcolonial analysis. The seminal text of postcolonial studies, Orientalism by Edward Said, describes the nineteenth-century European invention of the Orient as a geographic region considered racially and culturally distinct from, and inferior to, Europe. However, without the European invention of the Americas in the sixteenth century, sometimes referred to as Occidentalism, the later invention of the Orient would have been impossible.[12]: 56 This means that postcolonialism becomes problematic when applied to post-nineteenth-century Latin America.[37]: 94 Political decolonization Decolonization is largely political and historical: the end of the period of territorial domination of lands primarily in the global south by European powers. Decolonial scholars contend that colonialism did not disappear with political decolonization. It is important to note the vast differences in the histories, socioeconomics, and geographies of colonization in its various global manifestations. However, coloniality— meaning racialized and gendered socioeconomic and political stratification according to an invented Eurocentric standard—was common to all forms of colonization. Similarly, decoloniality in the form of challenges to this Eurocentric stratification manifested previous to de jure decolonization. Gandhi and Jinnah in India, Fanon in Algeria, Mandela in South Africa, and the early 20th-century Zapatistas in Mexico are all examples of decolonial projects that existed before decolonization. Postmodernism "Modernity" as a concept is complementary to coloniality. Coloniality is called "the darker side of western modernity".[12] The problematic aspects of coloniality are often overlooked when describing the totality of Western society, whose advent is instead often framed as the introduction of modernity and rationality, a concept critiqued by post-modern thinkers. However, this critique is largely "limited and internal to European history and the history of European ideas".[18]: 451 Although postmodern thinkers recognize the problematic nature of the notions of modernity and rationality, these thinkers often overlook the fact that modernity as a concept emerged when Europe defined itself as the center of the world. In this sense, those seen as part of the periphery are themselves part of Europe's self-definition.[38]: 13 To summarize, like modernity, postmodernity often reproduces the "Eurocentric fallacy" foundational to modernity. Therefore, rather than criticizing the terrors of modernity, decolonialism criticizes Eurocentric modernity and rationality because of the "irrational myth" that these conceal.[18]: 453-454 Decolonial approaches thus seek to "politicise epistemology from the experiences of those on the 'border,' not to develop yet another epistemology of politics".[38]: 13 |

関連する概念との区別 脱植民地性は、ポストコロニアリズム、脱植民地化、ポストモダニズムと混同されることが多い。しかし、脱植民地性の理論家たちは明確な区別を設けている。 ポストコロニアリズム ポストコロニアリズムは、有色人種、第三世界の知識人、あるいは民族集団による一般的な反対運動の実践として主流化されることが多い。[19]: 87 脱植民地性は、分析的アプローチおよびプログラム的アプローチの両方として、「ポストコロニアリズムの批判と理論は学術界における学術的変革のプロジェク トである」ため、「ポストコロニアリズムから離れ、それを超える」ものであるとされる。[18]: 452 この最後の指摘については議論の余地がある。ポストコロニアル学派の一部の学者は、ポストコロニアル批判と理論を分析的(学術的、理論的、認識論的)プロ ジェクトとプログラム的(実際的、政治的)スタンスの両方であるとみなしているからだ。[36]: 8 この意見の相違は、「ポストコロニアル主義」という用語の曖昧さの例である。この用語は、アルジェリア、19世紀の米国、19世紀のブラジルなどの文脈に おいて、植民地拡大と脱植民地化の分析 、一般的に限定的で無意識的に用いられる」という「ポストコロニアリズム」という用語の曖昧さの例である。この用語は、アルジェリア、19世紀の米国、 19世紀のブラジルなどの文脈において、植民地拡大と脱植民地化の分析に適用されてきた。 脱植民地化の研究者は、アメリカ大陸の植民地化がポストコロニアリズム分析の前提条件であると考える。ポストコロニアリズム研究の重要なテキストであるエ ドワード・サイード著『オリエンタリズム』では、19世紀のヨーロッパによるオリエントの地理的地域としての発明が、人種的・文化的にヨーロッパとは異な り、劣っているものとみなされたと説明されている。しかし、16世紀のヨーロッパによるアメリカ大陸の発見(西洋中心主義と呼ばれることもある)がなけれ ば、その後のオリエントの発見は不可能であった。[12]: 56 つまり、ポストコロニアリズムは19世紀以降のラテンアメリカに適用されると問題が生じるのである。[37]: 94 政治的な脱植民地化(→「脱植民地化」) 脱植民地化は、主に政治的・歴史的なものであり、主に南半球の土地がヨーロッパの列強によって領土支配されていた時代の終焉を意味する。脱植民地化の研究 者は、植民地主義は政治的な脱植民地化によって消滅したわけではないと主張している。 植民地化の歴史、社会経済、地理には、世界中でさまざまな形で現れた植民地化の間に大きな違いがあることに注目することが重要である。しかし、人種や性別 による社会経済的・政治的階層化を意味するコロニアリティ(植民地主義)は、欧州中心主義の基準によって作り出されたものであり、あらゆる形態の植民地化 に共通するものであった。同様に、この欧州中心主義的階層化への挑戦という形のコロニアリティは、法的な脱植民地化に先立って現れていた。インドのガン ディーやジンナー、アルジェリアのファノン、南アフリカのマンデラ、そしてメキシコの20世紀初頭のサパティスタは、いずれも脱植民地化以前から存在して いた脱植民地化プロジェクトの例である。 ポストモダニズム 「近代」という概念は、植民地主義と表裏一体である。植民地主義は「西洋近代の負の 側面」と呼ばれている。[12] 西洋社会の全体像を説明する際には、植民地主義の問題点がしばしば見落とされる。その代わりに、西洋社会の到来は近代性と合理性の導入として描かれること が多く、この概念はポストモダンの思想家たちによって批判されている。しかし、この批判は「ヨーロッパの歴史とヨーロッパの思想の歴史に限定されたもの」 である。[18]: 451 ポストモダンの思想家たちは、近代性や合理性の概念の問題点を認識しているが、近代性という概念がヨーロッパが世界の中心であると定義したときに生まれた という事実を見落としていることが多い。この意味で、周辺部と見なされているものは、ヨーロッパの自己定義の一部である。[38]: 13 要約すると、近代性と同様に、ポストモダニティは近代性の基礎をなす「ヨーロッパ中心主義の誤謬」をしばしば再生産する。したがって脱植民地化は、近代の 恐怖を批判するのではなく、近代が隠蔽する「非合理的な神話」を理由に、ヨーロッパ 中心主義的な近代と合理性を批判する。脱植民地化のアプローチは、このように「『境界』に位置する人々の経験から認識論を政治化」すること を目指しており、「政治の認識論をさらに発展させる」ことを目的としているわけではない。 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Decoloniality |

|

| En

una primera definición posible, por colonialidad se entiende

una matriz, esto es, una suerte de “estructura transhistórica de

dominación” (Añón y Rufer, 2018: 110), basada en un sistema

clasificatorio racializado y en una racialización de la explotación

capitalista,

anclada en la experiencia americana pero extendida a todo el orbe

a partir de la consolidación del sistema-mundo moderno/colonial,

y que se produce en el entrelazamiento de las dimensiones materiales y

simbólicas. Hablar de “colonialidad” implica reconstruir una

red de religaciones latinoamericanas (v. religación) y tramas de

diálogos Sur-Sur, escandidas por procesos políticos y sociales desde

mediados del siglo pasado. Esto es así porque el concepto de

“colonialidad” presenta un recorrido sinuoso en la teoría y la crítica

latinoamericanas. En el análisis de la colonialidad convergen

perspectivas

sociales, etnográficas, literarias e historiográficas; miradas críticas

hacia teorías metropolitanas eurocéntricas; múltiples diálogos en el

Sur Global; apuestas por nuevos archivos y críticas al canon. |

第

一に考えられる定義では、植民地性はマトリックス、つまり、人種差別的な階級制度と資本主義的搾取の人種化に基づく一種の「歴史的支配の横断的構造」

(Añón and Rufer, 2018:

110)として理解され、それはアメリカの経験に定着しているが、近代/植民地的世界システムの強化以降、全世界に拡大し、物質的・象徴的次元の織り成す

中で生み出されている。植民地性」を語ることは、ラテンアメリカの宗教(religación)のネットワークと、前世紀半ば以降の政治的・社会的プロセ

スによってスキャンダラスになった南と南の対話の網を再構築することを意味する。というのも、「植民地性」という概念は、ラテンアメリカの理論と批評にお

いて、曲がりくねった道筋を示しているからである。社会学的、民族学的、文学的、歴史学的な視点は、植民地性の分析、ヨーロッパ中心主義的なメトロポリタ

ン理論への批判的見解、グローバル・サウスにおける複数の対話、新たなアーカイブとカノン批判へのコミットメントに集約される。 |

| https://www.memoria.fahce.unlp.edu.ar/libros/pm.4967/pm.4967.pdf |

|

| Critique against descoloniality Olúfẹ́mi O. Táíwò ([o.lú.fɛ́.mi tá.í.wò]; born 1990)[1] is an American philosopher and professor of philosophy at Georgetown University.[2][3] He is the author of two books: Reconsidering Reparations and Elite Capture.[3] Grist.org has described him as "one of America’s most prominent philosophers" and "the most vocal philosopher working on issues related to climate change".[3] Táíwò regularly contributes articles to publications such as The New Yorker, The Guardian, and Foreign Policy, in addition to academic journals.[3] Early life and education Born in 1990, Táíwò lived in the San Francisco Bay Area for the first year of his life, before moving with his family to Cincinnati, Ohio, where there was a large Nigerian community.[1] His parents had both immigrated from Nigeria in the early 1980s to attend graduate school in the United States.[1] His mother worked in pharmacology at Procter & Gamble, while his father was an engineer who stayed at home to take care of his brother, who is autistic.[1] Táíwò earned his BA in philosophy from Indiana University and his PhD in philosophy from the University of California, Los Angeles.[4] Career Táíwò first gained widespread notice with an essay published in 2020 in The Philosopher on the "limitations of 'epistemic deference'".[5] In the essay, he argued that amplifying certain voices, including his own, on the basis of group membership in what is perceived as a marginalized community, did not necessarily solve fundamental problems and could impede formation of authentic relationships.[5] His book Elite Capture: How the Powerful Took Over Identity Politics and Everything Else builds on this piece, as well as a related essay which appeared in Boston Review.[5] His theoretical work is heavily influenced by the Black radical tradition, contemporary philosophy of language, materialist thought, social science, German transcendental philosophy, activist histories, and activist thinkers. His most recent book Elite Capture examines how elites have appropriated radical critiques of racial capitalism to further their own agendas.[4] Critical reception In a review for Race & Class, Franklin Obeng-Odoom calls Reconsidering Reparations "brilliant" despite "some serious faux pas".[6] Praising Táíwò for his "vigorous" and "serious" examination of time and space, Obeng-Odoom writes, "By building on his insightful critique of Rawlsian approaches to reparations, his powerful reconstruction of reparations and emphasis on how we need to take the remaking of the future into account in reconsidering reparations, it is possible to move past the shoots to the roots of ecological imperialism."[6] Writing in the academic journal Mind, Megan Blomfeld positions Táíwò as an "accessible writer and skilled storyteller" whose work was pitched at a general audience.[7] She notes that Táíwò devotes only 20 pages to a review of the philosophical literature on reparations – most likely not enough to dissuade proponents of other views.[7] Books Táíwò, Olúfẹ́mi O. (2022). Reconsidering Reparations. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-750891-6.[8][9][10][11][12][13][14][15] Táíwò, Olúfẹ́mi O. (2022). Elite Capture: How the Powerful Took Over Identity Politics (and Everything Else). Haymarket Books. ISBN 978-1-64259-735-6.[1][16][17][18][19][20][21][22][23][24][25][26][27] Further reading Elite Capture: Philosopher Olúfẹ́mi O. Táíwò on How the Powerful Took Over Identity Politics. "Elite Capture: How the Powerful Took Over Identity Politics". 18 January 2023 On Democracy Now!. Constructing Solidarity: An Interview with Olúfẹ́mi O. Táíwò "Constructing Solidarity: An Interview with Olúfẹ́mi O. Táíwò". 22 April 2022. Ritika Ramamurthy, Nonprofit Quarterly. |

脱植民地性への批判(論者) オルフェミ・O・タイウォ([o.lú.fɛ́.mi tá.í.wò]、1990年生まれ)[1]は、アメリカの哲学者であり、ジョージタウン大学の哲学教授である。[2][3] 著書に『 『賠償の再考』と『エリートによる呑み込み』の著者である。[3] Grist.orgは、彼を「アメリカで最も著名な哲学者の一人」であり、「気候変動に関連する問題に取り組む最も声高な哲学者」と評している。[3] タウォは学術誌に加え、『ニューヨーカー』、『ガーディアン』、『フォーリン・ポリシー』などの出版物にも定期的に寄稿している。[3] 幼少期と教育 1990年に生まれたタウォは、生後1年間をサンフランシスコ湾岸地域で過ごし、その後家族とともにナイジェリア人コミュニティの大きな存在するオハイオ 州シンシナティに移住した。1980年代初頭に米国の大学院へ進学するためにナイジェリアから移住した。[1] 母親はプロクター・アンド・ギャンブルで薬理学の研究に携わり、父親はエンジニアとして自宅で自閉症の弟の世話をしていた。[1] タイウォはインディアナ大学で哲学の学士号を、カリフォルニア大学ロサンゼルス校で哲学の博士号を取得した。[4] 経歴 タイウォは、2020年に『The Philosopher』誌に掲載された「「認識論的服従」の限界」と題するエッセイで広く知られるようになった。[5] このエッセイで彼は、周縁化されたコミュニティとみなされる集団に属する人々による特定の声の増幅は、必ずしも根本的な問題の解決にはつながらず、真の人間関係の形成を妨げる可能性があると主張した。[5] 著書『エリートによる乗っ取り: 権力者がアイデンティティ・ポリティクスとその他すべてを掌握した経緯』は、この論文と『ボストン・レビュー』に掲載された関連エッセイを基に書かれている。[5] 彼の理論的研究は、ブラック・ラディカルの伝統、現代の言語哲学、唯物論思想、社会科学、ドイツの超越論哲学、活動家の歴史、活動家の思想に強く影響を受 けている。彼の最新刊『エリート・キャプチャー』では、エリート層が人種資本主義に対する急進的な批判を自分たちの政策に利用してきた経緯を検証してい る。[4] 批評家の反応 Race & Class誌の書評で、フランクリン・オベング=オドゥームは「いくつかの深刻な誤り」があるにもかかわらず、『賠償の再考』を「素晴らしい」と評してい る。[6] オベング=オドゥームは、時間と空間に関する「活気のある」かつ「真剣な」調査を称賛し、 「ローリズ的な賠償へのアプローチに対する洞察力に富む批判、賠償に対する力強い再構築、そして賠償を再考するにあたり、未来の再構築を考慮する必要性に 対する強調を土台とすることで、生態学的帝国主義の芽を根こそぎにすることが可能となる」と書いている。 学術誌『Mind』に寄稿したメーガン・ブロムフィールドは、タウォを「一般読者向けの作品を執筆する、親しみやすい作家であり、優れたストーリーテ ラー」と位置づけている。[7] 彼女は、タウォが返還に関する哲学文献のレビューに20ページしか割いていないことを指摘しているが、おそらく他の見解の支持者たちを説得するには不十分 だろう。[7] 書籍 Táíwò, Olúfẹ́mi O. (2022). Reconsidering Reparations. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-750891-6.[8][9][10][11][12][13][14][15] Táíwò, Olúfẹ́mi O. (2022). エリートによる支配:権力者がアイデンティティ・ポリティクス(およびその他すべて)を乗っ取った方法. Haymarket Books. ISBN 978-1-64259-735-6. [1][16][17][18][19][20][21][22][23][24][25][26][27] さらに読む エリートによる支配:哲学者オルフェミ・O・タイウォ[Olúfẹ́mi O. Táíwò]が語る、権力者たちがアイデンティティ・ポリティクスを乗っ取った経緯。「エリートによる支配:権力者たちがアイデンティティ・ポリティクスを乗っ取った経緯」。2023年1月18日、オン・デモクラシー・ナウ!。 連帯の構築:オルフェミ・O・タイウォへのインタビュー「連帯の構築:オルフェミ・O・タイウォへのインタビュー」。2022年4月22日。リティカ・ラマムルシー、非営利四半期。 |

| Reparations for slavery have

become a reinvigorated topic for public debate over the last decade.

Most theorizing about reparations treats it as a social justice project

- either rooted in reconciliatory justice

focused on making amends in the present; or, they focus on the past,

emphasizing restitution for historical wrongs. Olúfemi O. Táíwò argues

that neither approach is optimal, and advances a different case for

reparations - one rooted in a hopeful future that tackles the issue of

climate change head on, with distributive justice

at its core. This view, which he calls the "constructive" view of

reparations, argues that reparations should be seen as a

future-oriented project engaged in building a better social order; and

that the costs of building a more equitable world should be distributed

more to those who have inherited the moral liabilities of past

injustices. This approach to reparations, as Táíwò shows, has deep and surprising roots in the thought of Black political thinkers such as James Baldwin, Martin Luther King Jr, and Nkechi Taifa, as well as mainstream political philosophers like John Rawls, Charles Mills, and Elizabeth Anderson. Táíwò's project has wide implications for our views of justice, racism, the legacy of colonialism, and climate change policy. https://www.amazon.co.jp/Reconsidering-Reparations-Philosophy-Olufemi-Taiwo/dp/0197508898/ref=sr_1_1 |

奴隷制に対する賠償は、ここ10年ほど、再び活発な議論のテーマとなっ

ている。賠償に関するほとんどの理論は、それを社会正義のプロジェクトとして扱っている。つまり、現在の償いに焦点を当てた和解的正義に根ざしているか、

あるいは、過去の歴史的な不正に対する返還を強調している。オルフェミ・O・タイウォは、どちらのアプローチも最適ではないと主張し、賠償に関する異なる

見解を提示している。それは、分配的正義を核として、気候変動の問題に正面から取り組む希望に満ちた未来に根ざしたものである。彼はこれを「建設的」な賠

償の考え方と呼んでいるが、賠償はより良い社会秩序の構築を目指す未来志向のプロジェクトとして捉えられるべきであり、より公平な世界を築くためのコスト

は、過去の不正の道徳的責任を継承している人々に多く分配されるべきであると主張している。 この賠償に対するアプローチは、タイウォが示すように、ジェームズ・ボールドウィン、マーティン・ルーサー・キング・ジュニア、ンケチ・タイファといった 黒人政治思想家や、ジョン・ロールズ、チャールズ・ミルズ、エリザベス・アンダーソンといった主流派の政治哲学者の思想に深く、そして意外なほど根ざして いる。タイウォのプロジェクトは、正義、人種差別、植民地主義の遺産、気候変動政策に対する私たちの見解に幅広い影響を及ぼす。 |

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆