文化人類学リミックス

Cultural Anthropology Remix

☆文化人類学(Cultural

anthropology)

は、人類間の文化的差異を研究対象とする人類学の一分野である。これは、文化的差異を仮定された人類学的恒常性の部分集合と捉える社会人類学とは対照的で

ある。社会文化人類学という用語は、文化人類学と社会人類学の両方の伝統を含む。[1]

人類学者たちは、文化を通じて人々が非遺伝的な方法で環境に適応できると指摘している。したがって、異なる環境に住む人民はしばしば異なる文化を持つこと

になる。人類学理論の多くは、ローカル(特定の文化)とグローバル(普遍的な人間性、あるいは異なる場所・状況にいる人々間のつながりの網)の間の緊張関

係への理解と関心から生まれた。[2]

文化人類学は豊かな方法論を有している。参与観察(研究地での長期滞在を要するため「フィールドワーク」とも呼ばれる)、インタビュー、調査などが含まれ

る(→「文化人類学入門」「文化人類学ガイドブック[教科書]」)。

| Cultural

anthropology is a branch of anthropology focused on the study of

cultural variation among humans. It is in contrast to social

anthropology, which perceives cultural variation as a subset of a

posited anthropological constant. The term sociocultural anthropology

includes both cultural and social anthropology traditions.[1] Anthropologists have pointed out that through culture, people can adapt to their environment in non-genetic ways, so people living in different environments will often have different cultures. Much of anthropological theory has originated in an appreciation of and interest in the tension between the local (particular cultures) and the global (a universal human nature, or the web of connections between people in distinct places/circumstances).[2] Cultural anthropology has a rich methodology, including participant observation (often called fieldwork because it requires the anthropologist spending an extended period of time at the research location), interviews, and surveys.[3] |

文化人類学は、人類間の文化的差異を研究対象とする人類学の一分野であ

る。これは、文化的差異を仮定された人類学的恒常性の部分集合と捉える社会人類学とは対照的である。社会文化人類学という用語は、文化人類学と社会人類学

の両方の伝統を含む。[1] 人類学者たちは、文化を通じて人々が非遺伝的な方法で環境に適応できると指摘している。したがって、異なる環境に住む人民はしばしば異なる文化を持つこと になる。人類学理論の多くは、ローカル(特定の文化)とグローバル(普遍的な人間性、あるいは異なる場所・状況にいる人々間のつながりの網)の間の緊張関 係への理解と関心から生まれた。[2] 文化人類学は豊かな方法論を有している。参与観察(研究地での長期滞在を要するため「フィールドワーク」とも呼ばれる)、インタビュー、調査などが含まれ る。[3] |

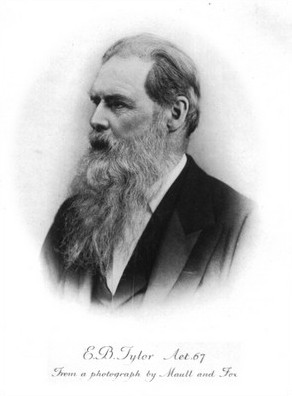

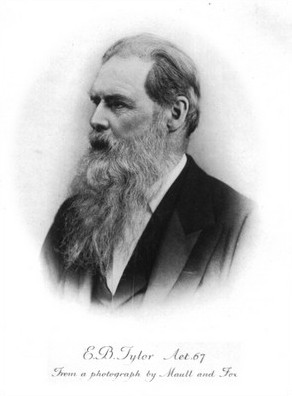

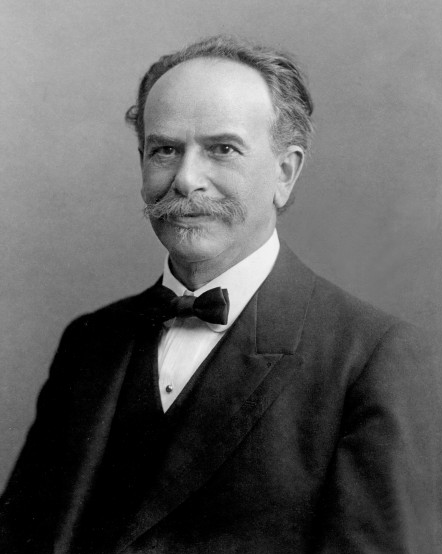

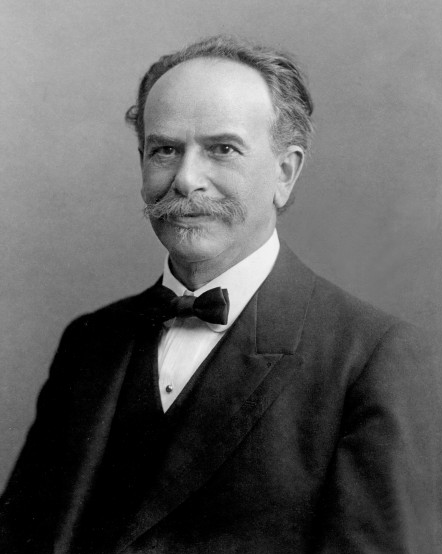

| History This section may require cleanup to meet Wikipedia's quality standards. The specific problem is: this currently is not a history of cultural anthropology, but of specific terms. It also does not explain the outdated terminology used. Please help improve this section if you can. (August 2020) (Learn how and when to remove this message)  Edward Burnett Tylor, founder of cultural anthropology Modern anthropology emerged in the 19th century, coinciding with significant developments in the Western world. These changes sparked a renewed interest in understanding humankind, particularly, its origins, unity, and plurality. However, it was in the early 20th century that cultural anthropology began to adopt a more pluralistic perspective on cultures and societies.[4] The term itself was coined by the Boas circle, who advanced the key theoretical frameworks of cultural relativism and historical particularism.[5] Cultural anthropology emerged in the late 19th century, shaped by debates over what constituted "primitive" versus "civilized" societies, an issue that preoccupied not only Freud, but many of his contemporaries. Colonialism expansion increasingly brought European thinkers into direct or indirect contact with "primitive others".[6] The first generation of cultural anthropologists were interested in the relative status of various humans, some of whom had modern advanced technologies, while others lacked anything but face-to-face communication techniques and still lived a Paleolithic lifestyle. +++++++++++++++++++++ Historical particularism (coined by Marvin Harris in 1968)[1] is widely considered the first American anthropological school of thought. Closely associated with Franz Boas and the Boasian approach to anthropology, historical particularism rejected the cultural evolutionary model that had dominated anthropology until Boas. It argued that each society is a collective representation of its unique historical past. Boas rejected parallel evolutionism, the idea that all societies are on the same path and have reached their specific level of development the same way all other societies have.[2] Instead, historical particularism showed that societies could reach the same level of cultural development through different paths.[2] Boas suggested that diffusion, trade, corresponding environment, and historical accident may create similar cultural traits.[2] Three traits, as suggested by Boas, are used to explain cultural customs: environmental conditions, psychological factors, and historical connections, history being the most important (hence the school's name).[2] Critics of historical particularism argue that it is anti-theoretical because it doesn't seek to make universal theories, applicable to all the world's cultures. Boas believed that theories would arise spontaneously once enough data was collected. This school of anthropological thought was the first to be uniquely American and Boas (his school of thought included) was, arguably, the most influential anthropological thinker in American history. References 1. Harris, Marvin: The Rise of Anthropological Theory: A History of Theories of Culture. 1968. (Reissued 2001) New York: Thomas Y. Crowell Company 2. Boas, Franz (December 1920). "The Methods of Ethnology". American Anthropologist. 22 (4): 311–321. doi:10.1525/aa.1920.22.4.02a00020. JSTOR 660328. Further reading Calhoun, Craig J., ed. (2002). "historical particularism". Dictionary of the social sciences. Oxford University Press. p. 212. ISBN 978-0-19-512371-5. Card, Claudia (1996). The unnatural lottery: character and moral luck. Temple University Press. p. 10. ISBN 978-1-56639-453-6. Darnell, Regna (2001). Invisible genealogies: a history of Americanist anthropology. University of Nebraska Press. p. 34. ISBN 978-0-8032-6629-2. Sanderson, Stephen K. (1997). "Historical particularism". In Barfield, Thomas (ed.). The dictionary of anthropology. Wiley-Blackwell. p. 237. ISBN 978-1-57718-057-9. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Historical_particularism |

歴史 この節はウィキペディアの品質基準を満たすために整理が必要かもしれない。具体的な問題は、現在これは文化人類学の歴史ではなく、特定の用語の歴史となっ ている点だ。また、使用されている時代遅れの用語についても説明がない。可能であればこの節の改善に協力してほしい。(2020年8月)(このメッセージ を削除する方法と時期について学ぶ)  文化人類学の創始者エドワード・バーネット・タイラー 現代人類学は19世紀に台頭し、西洋世界における重要な発展と時期を同じくした。これらの変化は人類、特にその起源・統一性・多様性を理解する新たな関心 を喚起した。しかし文化人類学が文化や社会に対してより多元的な視点を採用し始めたのは20世紀初頭のことである。[4] この用語自体はボアズの学派によって造語された。彼らは文化相対主義と歴史的個別主義(下記)という主要な理論的枠組みを推進した。[5] 文化人類学は19世紀後半に現れた。その形成には「原始的」社会と「文明的」社会を何で区別するかという論争が影響していた。この問題はフロイトだけでな く、彼の同時代人の多くをも悩ませた。植民地主義の拡大に伴い、ヨーロッパの思想家たちは「原始的な他者」と直接的・間接的に接触する機会が増えた。 [6] 第一世代の文化人類学者は、様々な人類の相対的な地位に関心を寄せた。中には近代的な高度技術を持つ者もいれば、対面コミュニケーション技術しか持たず旧 石器時代の生活様式を続ける者もいたのである。 +++++++++++++++++++++ 歴史的個別主義(マービン・ハリスが1968年に提唱した概念)[1]は、アメリカ人類学の最初の学派と広く見なされている。 フランツ・ボアスとボアズ派人類学と密接に関連し、歴史的個別主義はボアス以前の人類学を支配していた文化進化論モデルを否定した。各社会はその独自の歴 史的過去を集団的に体現していると主張したのである。ボアズは並行進化論、すなわち全ての社会が同じ道を辿り、他の社会と同じ方法で特定の文化発展段階に 到達したという考えを否定した[2]。代わりに歴史的個別主義は、社会が異なる経路を通じて同じ文化発展段階に到達し得ることを示した。[2] ボアズは、拡散、交易、対応する環境、歴史的偶然が類似した文化的特性を生み出す可能性を示唆した[2]。ボアズが提唱した文化的習俗を説明する三つの特性は、環境条件、心理的要因、歴史的連関であり、中でも歴史が最も重要である(これが学派名の由来である)。[2] 歴史的個別主義の批判者は、この学派が世界中の文化に適用可能な普遍的理論を構築しようとしないため、反理論的であると主張する。ボアズは、十分なデータ が収集されれば理論は自発的に生まれると信じていた。この人類学的思想の学派は、アメリカ独自の最初の学派であり、ボアズ(彼の思想体系を含む)は、おそ らくアメリカ史上最も影響力のある人類学的思想家であった。 参考文献 1. ハリス、マーヴィン:『人類学理論の興隆:文化理論の歴史』。1968年。(2001年再版)ニューヨーク:トーマス・Y・クロウェル社 2. ボアズ、フランツ(1920年12月)。「民族学の方法」。『アメリカ人類学者』。22巻4号:311–321頁。doi:10.1525/aa.1920.22.4.02a00020. JSTOR 660328. 追加文献(さらに読む) カルフーン、クレイグ・J. 編(2002)。「歴史的個別主義」。『社会科学辞典』。オックスフォード大学出版局。p. 212。ISBN 978-0-19-512371-5. カード、クローディア (1996). 『不自然なくじ引き:性格と道徳的幸運』. テンプル大学出版局. p. 10. ISBN 978-1-56639-453-6. ダーネル、レグナ(2001)。『見えない系譜:アメリカ主義人類学の歴史』。ネブラスカ大学出版局。34頁。ISBN 978-0-8032-6629-2。 Sanderson, Stephen K. (1997). 「歴史的個別主義」. Barfield, Thomas (編). 『人類学辞典』. Wiley-Blackwell. p. 237. ISBN 978-1-57718-057-9. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Historical_particularism |

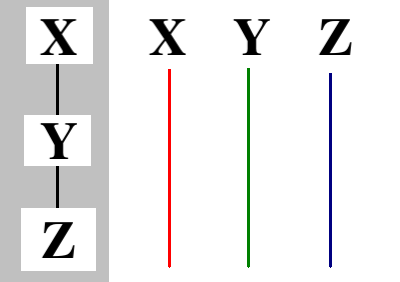

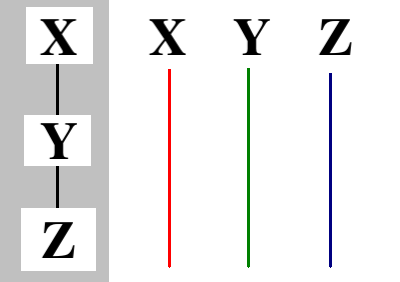

| Theoretical foundations The concept of culture One of the earliest articulations of the anthropological meaning of the term "culture" came from Sir Edward Tylor: "Culture, or civilization, taken in its broad, ethnographic sense, is that complex whole which includes knowledge, belief, art, morals, law, custom, and any other capabilities and habits acquired by man as a member of society."[7] The term "civilization" later gave way to definitions given by V. Gordon Childe, with culture forming an umbrella term and civilization becoming a particular kind of culture.[8] Kay Milton, former Director of Anthropology Research at Queen's University Belfast, distinguishes between general and specific cultures. This means culture can be something applied to all human beings or it can be specific to a certain group of people such as African American culture or Irish American culture. Specific cultures are structured systems which means they are organized very specifically and adding or taking away any element from that system may disrupt it.[9] The critique of evolutionism Anthropology is concerned with the lives of people in different parts of the world, particularly in relation to the discourse of beliefs and practices. In addressing this question, ethnologists in the 19th century divided into two schools of thought. Some, like Grafton Elliot Smith, argued that different groups must have learned from one another somehow, however indirectly; in other words, they argued that cultural traits spread from one place to another, or "diffused".  In the unilineal evolution model at left, all cultures progress through set stages, while in the multilineal evolution model at right, distinctive culture histories are emphasized. Other ethnologists argued that different groups had the capability of creating similar beliefs and practices independently. Some of those who advocated "independent invention", like Lewis Henry Morgan, additionally supposed that similarities meant that different groups had passed through the same stages of cultural evolution (See also classical social evolutionism). Morgan, in particular, acknowledged that certain forms of society and culture could not possibly have arisen before others. For example, industrial farming could not have been invented before simple farming, and metallurgy could not have developed without previous non-smelting processes involving metals (such as simple ground collection or mining). Morgan, like other 19th century social evolutionists, believed there was a more or less orderly progression from the primitive to the civilized. 20th-century anthropologists largely reject the notion that all human societies must pass through the same stages in the same order, on the grounds that such a notion does not fit the empirical facts. Some 20th-century ethnologists, like Julian Steward, have instead argued that such similarities reflected similar adaptations to similar environments. Although 19th-century ethnologists saw "diffusion" and "independent invention" as mutually exclusive and competing theories, most ethnographers quickly reached a consensus that both processes occur, and that both can plausibly account for cross-cultural similarities. But these ethnographers also pointed out the superficiality of many such similarities. They noted that even traits that spread through diffusion often were given different meanings and function from one society to another. Analyses of large human concentrations in big cities, in multidisciplinary studies by Ronald Daus, show how new methods may be applied to the understanding of man living in a global world and how it was caused by the action of extra-European nations, so highlighting the role of Ethics in modern anthropology. Accordingly, most of these anthropologists showed less interest in comparing cultures, generalizing about human nature, or discovering universal laws of cultural development, than in understanding particular cultures in those cultures' own terms. Such ethnographers and their students promoted the idea of "cultural relativism", the view that one can only understand another person's beliefs and behaviors in the context of the culture in which they live or lived. Others, such as Claude Lévi-Strauss (who was influenced both by American cultural anthropology and by French Durkheimian sociology), have argued that apparently similar patterns of development reflect fundamental similarities in the structure of human thought (see structuralism). By the mid-20th century, the number of examples of people skipping stages, such as going from hunter-gatherers to post-industrial service occupations in one generation, were so numerous that 19th-century evolutionism was effectively disproved.[10] |

理論的基盤 文化の概念 人類学における「文化」という用語の意味を最初に明確に示したのはエドワード・タイラー卿である。「文化、あるいは文明とは、広義の民族誌的意味におい て、知識、信念、芸術、道徳、法律、習慣、その他あらゆる能力や習慣を含む複雑な全体を指す。これらは人間が社会の一員として獲得したものだ」 [7] 「文明」という用語は後にV・ゴードン・チャイルドによる定義に取って代わられ、文化が包括的な概念となり、文明は文化の一形態となった。[8] ベルファスト・クイーンズ大学元人類学研究部長ケイ・ミルトンは、一般文化と特定文化を区別する。つまり文化とは全人類に適用されるものもあれば、アフリ カ系アメリカ人文化やアイルランド系アメリカ人文化のように特定集団に固有のものもある。特定文化は構造化されたシステムであり、非常に厳密に組織化され ているため、そのシステムから要素を加減すると崩壊する可能性がある。[9] 進化論批判 人類学は、世界各地域の人々の生活、特に信念や慣行に関する言説を扱う学問である。この問題に取り組むにあたり、19世紀の民族学者たちは二つの学派に分 かれた。グラフトン・エリオット・スミスのような学派は、異なる集団が何らかの形で、たとえ間接的であっても互いに学び合ったに違いないと主張した。つま り、文化的特性は一箇所から別の場所へ伝播、すなわち「拡散」したと論じたのである。  左の単線的進化モデルでは、全ての文化が定められた段階を経て進歩する。一方、右の多線的進化モデルでは、各文化の独自の歴史が強調される。 他の民族学者たちは、異なる集団が独立して類似した信仰や慣習を生み出す能力を持つと主張した。「独立発明説」を提唱したルイス・ヘンリー・モーガンらの 一部は、さらに類似性が異なる集団が文化進化の同じ段階を経たことを意味すると推測した(古典的社会進化論も参照)。特にモーガンは、特定の社会形態や文 化形態が他の形態より先に発生することは不可能だと認めていた。例えば工業的農業は単純な農業より先に発明され得ず、冶金術は金属を扱う非精錬プロセス (単純な採集や採掘など)なしには発展し得ない。モーガンは他の19世紀の社会進化論者と同様、原始的な状態から文明的な状態へ、ほぼ秩序立った進展がある と信じていた。 20世紀の人類学者は、全ての人間社会が同じ順序で同じ段階を経なければならないという考えを、実証的事実と合致しないとしてほぼ否定している。ジュリア ン・スチュワートのような20世紀の民族学者たちは、むしろそうした類似性は、類似した環境への適応が反映された結果だと主張した。19世紀の民族学者た ちは「拡散」と「独立発明」を互いに排他的で競合する理論と見なしていたが、ほとんどのエスノグラファーはすぐに、両方のプロセスが起きていること、そし て両方が異文化間の類似性を説明しうるという点で合意に達した。しかしこれらのエスノグラファーはまた、多くの類似性が表面的なものであることも指摘し た。拡散によって広まった特徴でさえ、社会によって異なる意味や機能を与えられていることが多いと彼らは述べた。ロナルド・ダウスの学際的研究による大都 市における大規模な人間集積の分析は、グローバルな世界に住む人間を理解するために新たな方法がどのように適用され得るか、そしてそれがヨーロッパ以外の 諸国民の活動によって引き起こされたことを示し、現代人類学における倫理の役割を浮き彫りにした。 したがって、これらの人類学者の多くは、文化の比較や人間性の一般化、文化発展の普遍的法則の発見よりも、各文化をその文化自身の基準で理解することに関 心を示した。こうしたエスノグラファーとその弟子たちは「文化的相対主義」の思想を推進した。これは他者の信念や行動を、彼らが生きる(あるいは生きた) 文化の文脈においてのみ理解できるという見解である。 一方、クロード・レヴィ=ストロース(アメリカの文化人類学とフランスのデュルケーム派社会学の両方に影響を受けた)のような学者たちは、一見類似した発 展パターンは、人間の思考構造における根本的な類似性を反映していると主張した(構造主義参照)。20世紀半ばまでに、狩猟採集社会から一世代でポスト産 業社会のサービス業へ移行するなど、段階を飛び越える事例が数多く確認されたため、19世紀の進化論は事実上否定されたのである。 |

| Cultural relativism Main article: Cultural relativism Cultural relativism is a principle that was established as axiomatic in anthropological research by Franz Boas and later popularized by his students. Boas first articulated the idea in 1887: "...civilization is not something absolute, but ... is relative, and ... our ideas and conceptions are true only so far as our civilization goes."[11] Although Boas did not coin the term, it became common among anthropologists after Boas' death in 1942, to express their synthesis of a number of ideas Boas had developed. Boas believed that the sweep of cultures, to be found in connection with any sub-species, is so vast and pervasive that there cannot be a relationship between culture and race.[12] Cultural relativism involves specific epistemological and methodological claims. Whether or not these claims require a specific ethical stance is a matter of debate. This principle should not be confused with moral relativism. Cultural relativism was in part a response to Western ethnocentrism. Ethnocentrism may take obvious forms, in which one consciously believes that one's people's arts are the most beautiful, values the most virtuous, and beliefs the most truthful. Boas, originally trained in physics and geography, and heavily influenced by the thought of Kant, Herder, and von Humboldt, argued that one's culture may mediate and thus limit one's perceptions in less obvious ways. This understanding of culture confronts anthropologists with two problems: first, how to escape the unconscious bonds of one's own culture, which inevitably bias our perceptions of and reactions to the world, and second, how to make sense of an unfamiliar culture. The principle of cultural relativism thus forced anthropologists to develop innovative methods and heuristic strategies.[citation needed] Boas and his students realized that if they were to conduct scientific research in other cultures, they would need to employ methods that would help them escape the limits of their own ethnocentrism. One such method is that of ethnography. This method advocates living with people of another culture for an extended period of time to learn the local language and be enculturated, at least partially, into that culture. In this context, cultural relativism is of fundamental methodological importance, because it calls attention to the importance of the local context in understanding the meaning of particular human beliefs and activities. Thus, in 1948 Virginia Heyer wrote, "Cultural relativity, to phrase it in starkest abstraction, states the relativity of the part to the whole. The part gains its cultural significance by its place in the whole, and cannot retain its integrity in a different situation."[13] |

文化相対主義 主な記事: 文化相対主義 文化相対主義とは、人類学研究においてフランツ・ボアズによって公理として確立され、後にその弟子たちによって普及した原理である。ボアスは1887年に 初めてこの考えを次のように述べた:「文明とは絶対的なものではなく、相対的なものであり、我々の考えや概念は、我々の文明の範囲内でのみ真実である」 [11] ボアズ自身がこの用語を造語したわけではないが、1942年の彼の死後、人類学者たちの間で、ボアズが展開した数々の思想を統合する概念として定着した。 ボアズは、あらゆる亜種と結びついて見出される文化の広がりはあまりに広大かつ遍在的であるため、文化と人種との間に何らかの関係性を認めることは不可能 だと考えていた。[12] 文化相対主義は、特定の認識論的・方法論的主張を含む。これらの主張が特定の倫理的立場を必要とするかどうかは議論の余地がある。この原理は道徳的相対主 義と混同すべきではない。 文化相対主義は、西洋の民族中心主義への反応の一部であった。民族中心主義は明白な形態をとることもあり、自民族の芸術が最も美しく、価値観が最も高潔 で、信仰が最も真実であると意識的に信じる場合がある。物理学と地理学を学んだボアズは、カント、ヘルダー、フォン・フンボルトの思想に強く影響を受け、 文化がより間接的な方法で個人の認識を媒介し制限し得ると主張した。この文化理解は人類学者に二つの課題を突きつける。第一に、世界に対する認識や反応を 必然的に歪める自文化の無意識の束縛からいかに脱却するか。第二に、未知の文化をいかに理解するかである。こうして文化相対主義の原理は、人類学者たちに 革新的な方法論と発見的手法の戦略を開発することを強いたのである。 ボアズとその弟子たちは、他文化において科学的な研究を行うには、自らの民族中心主義の限界から逃れる手助けとなる方法を採用する必要があることに気づい た。その手法の一つが民族誌学である。この方法論は、他文化の人々と長期にわたり共同生活し、現地の言語を習得し、少なくとも部分的にその文化に同化する ことを提唱する。この文脈において文化相対主義は方法論的に極めて重要である。なぜなら、特定の人間の信念や活動の意味を理解する上で、現地の文脈が重要 であることを強調するからだ。したがって、1948年にバージニア・ヘイヤーはこう記している。「文化相対主義とは、最も抽象的に表現すれば、部分と全体 の相対性を示すものである。部分は全体における位置によって文化的意義を獲得し、異なる状況ではその完全性を保てない」[13] |

| Theoretical approaches Actor–network theory Cultural materialism Culture theory Feminist anthropology Functionalism Symbolic and interpretive anthropology Political economy in anthropology Practice theory Structuralism Post-structuralism Systems theory in anthropology |

理論的アプローチ アクター・ネットワーク理論(ANT) 文化的唯物論 文化理論 フェミニスト人類学 機能主義 象徴的・解釈的人類学 人類学における政治経済学 実践理論 構造主義 ポスト構造主義 人類学におけるシステム理論 |

| Comparison with social anthropology The rubric cultural anthropology is generally applied to ethnographic works that are holistic in approach, are oriented to the ways in which culture affects individual experience or aim to provide a rounded view of the knowledge, customs, and institutions of a people. Social anthropology is a term applied to ethnographic works that attempt to isolate a particular system of social relations such as those that comprise domestic life, economy, law, politics, or religion, give analytical priority to the organizational bases of social life, and attend to cultural phenomena as somewhat secondary to the main issues of social scientific inquiry.[14] Parallel with the rise of cultural anthropology in the United States, social anthropology developed as an academic discipline in Britain and in France.[15] |

社会人類学との比較 文化人類学という分類は、概して全体論的アプローチを取る民族誌的研究、文化が個人の経験に与える影響を考察する研究、あるいは人民の知識・慣習・制度を 包括的に捉えようとする研究に適用される。社会人類学という用語は、家庭生活、経済、法、政治、宗教などを構成する特定の社会関係体系を分離し、社会生活 の組織的基盤を分析的に優先させ、文化現象を社会科学的な探究の主要課題に対してやや二次的なものとして扱うエスノグラファーによって行われる民族誌的研 究に適用される。[14] アメリカにおける文化人類学の台頭と並行して、社会人類学はイギリスとフランスにおいて学術分野として発展した。[15] |

Foundational thinkers Lewis Henry Morgan Lewis Henry Morgan (1818–1881), a lawyer from Rochester, New York, became an advocate for and ethnological scholar of the Iroquois. His comparative analyses of religion, government, material culture, and especially kinship patterns proved to be influential contributions to the field of anthropology. Like other scholars of his day (such as Edward Tylor), Morgan argued that human societies could be classified into categories of cultural evolution on a scale of progression that ranged from savagery, to barbarism, to civilization. Generally, Morgan used technology (such as bowmaking or pottery) as an indicator of position on this scale. |

基礎的な思想家 ルイス・ヘンリー・モーガン ルイス・ヘンリー・モーガン(1818年~1881年)は、ニューヨーク州ロチェスター出身の弁護士であり、イロコイ族の擁護者および民族学者となった。 宗教、政府、物質文化、そして特に親族関係パターンに関する彼の比較分析は、人類学の分野に多大な貢献をした。当時の他の学者(エドワード・タイラーな ど)と同様、モーガンは、人間社会は、野蛮、未開、文明という進歩の尺度で、文化の進化のカテゴリーに分類できると主張した。一般的に、モーガンはこの尺 度の位置を示す指標として、技術(弓作りや陶器など)を用いた。 |

| Franz Boas, founder of the modern discipline Main article: Boasian anthropology  Franz Boas (1858–1942), one of the pioneers of modern anthropology, often called the "Father of American Anthropology" Franz Boas (1858–1942) established academic anthropology in the United States in opposition to Morgan's evolutionary perspective. His approach was empirical, skeptical of overgeneralizations, and eschewed attempts to establish universal laws. For example, Boas studied immigrant children to demonstrate that biological race was not immutable, and that human conduct and behavior resulted from nurture, rather than nature. Influenced by the German tradition, Boas argued that the world was full of distinct cultures, rather than societies whose evolution could be measured by the extent of "civilization" they had. He believed that each culture has to be studied in its particularity, and argued that cross-cultural generalizations, like those made in the natural sciences, were not possible.[citation needed] In doing so, he fought discrimination against immigrants, blacks, and indigenous peoples of the Americas.[16] Many American anthropologists adopted his agenda for social reform, and theories of race continue to be popular subjects for anthropologists today. The so-called "Four Field Approach" has its origins in Boasian Anthropology, dividing the discipline in the four crucial and interrelated fields of sociocultural, biological, linguistic, and archaic anthropology (e.g. archaeology). Anthropology in the United States continues to be deeply influenced by the Boasian tradition, especially its emphasis on culture. |

フランツ・ボアズ、現代人類学の創始者 詳細記事: ボアズ派人類学  フランツ・ボアズ(1858–1942)は現代人類学の先駆者の一人であり、「アメリカ人類学の父」と呼ばれることが多い フランツ・ボアズ(1858–1942)は、モーガンの進化論的視点に反対して、アメリカにおける学術的人類学を確立した。彼のアプローチは経験主義的で あり、過度の一般化を疑い、普遍的な法則を確立しようとする試みを避けた。例えばボアズは移民の子どもたちを研究し、生物学的人種は不変ではなく、人間の 行動や振る舞いは「生まれ」ではなく「育ち」の結果であることを示した。 ドイツの伝統に影響を受けたボアズは、世界は「文明」の程度によって進化を測れる社会ではなく、それぞれ異なる文化に満ちていると主張した。彼は各文化は その特殊性の中で研究されるべきだと考え、自然科学で見られるような文化横断的な一般化は不可能だと主張した。[出典が必要] こうした活動を通じて、彼は移民、黒人、アメリカ先住民に対する差別と戦った。[16] 多くのアメリカ人類学者は彼の社会改革の課題を継承し、人種理論は今日でも人類学者の間で人気のある研究テーマであり続けている。いわゆる「四分野アプ ローチ」はボアズ派人類学に起源を持ち、この学問を社会文化人類学、生物人類学、言語人類学、そして古代人類学(考古学など)という四つの重要かつ相互に 関連する分野に分割した。アメリカ合衆国における人類学は、特に文化への重点を置く点で、今もなおボアズ派の伝統に深く影響され続けている。 |

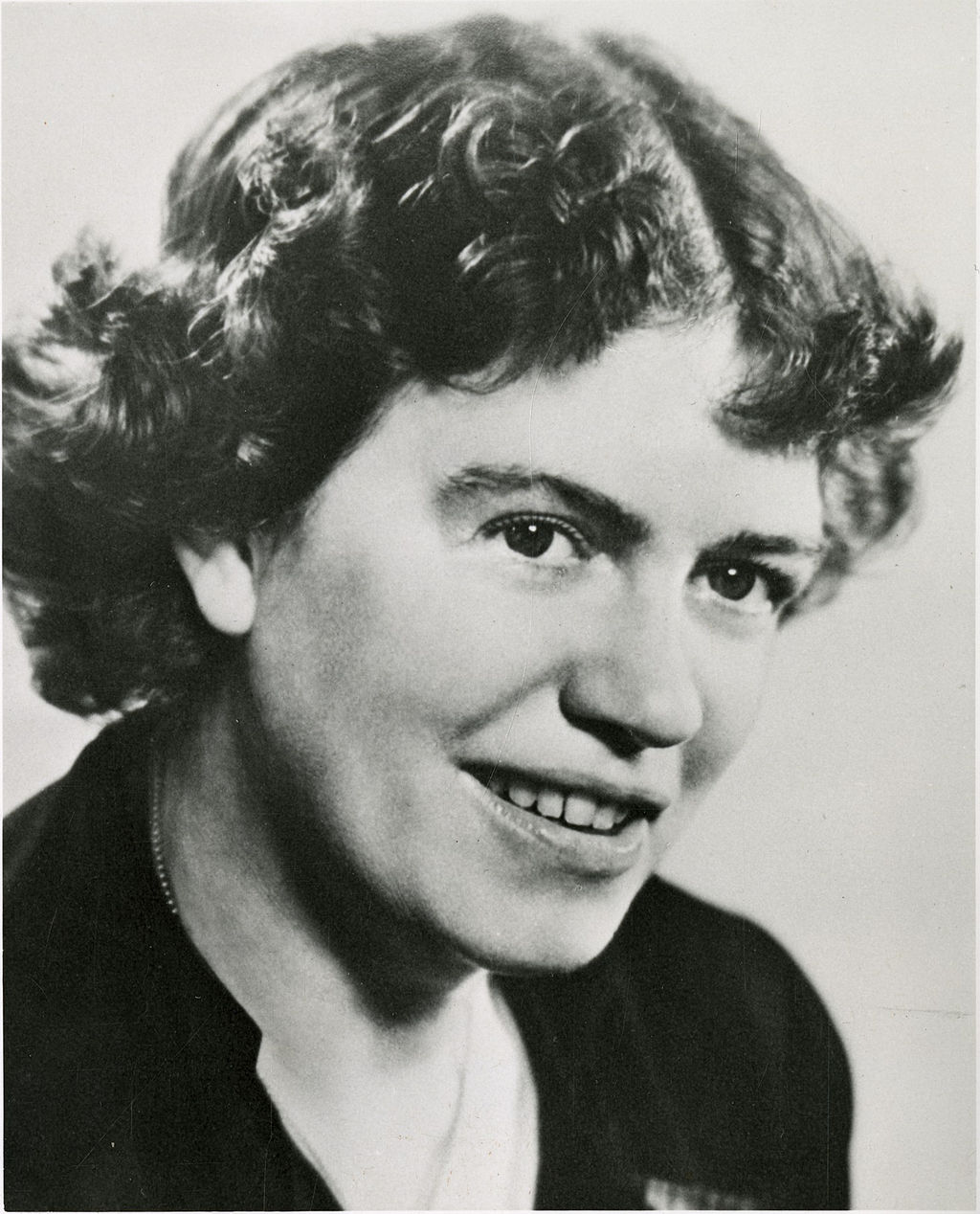

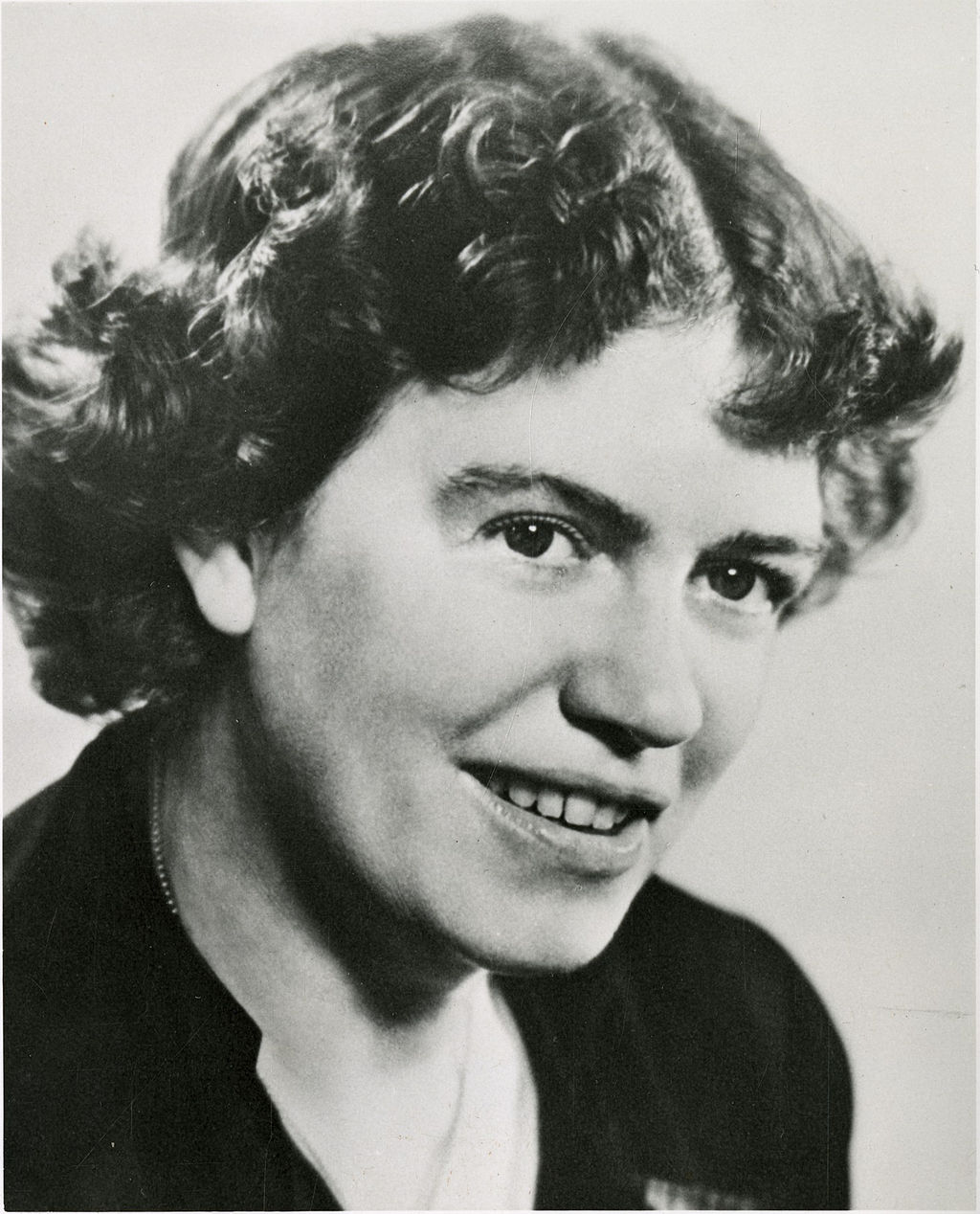

| Kroeber, Mead, and Benedict Boas used his positions at Columbia University and the American Museum of Natural History (AMNH) to train and develop multiple generations of students. His first generation of students included Alfred Kroeber, Robert Lowie, Edward Sapir, and Ruth Benedict, who each produced richly detailed studies of indigenous North American cultures. They provided a wealth of details used to attack the theory of a single evolutionary process. Kroeber and Sapir's focus on Native American languages helped establish linguistics as a truly general science and free it from its historical focus on Indo-European languages. The publication of Alfred Kroeber's textbook Anthropology (1923) marked a turning point in American anthropology. After three decades of amassing material, Boasians felt a growing urge to generalize. This was most obvious in the 'Culture and Personality' studies carried out by younger Boasians such as Margaret Mead and Ruth Benedict. Influenced by psychoanalytic psychologists including Sigmund Freud and Carl Jung, these authors sought to understand the way that individual personalities were shaped by the wider cultural and social forces in which they grew up.  Though such works as Mead's Coming of Age in Samoa (1928) and Benedict's The Chrysanthemum and the Sword (1946) remain popular with the American public, Mead and Benedict never had the impact on the discipline of anthropology that some expected. Boas had planned for Ruth Benedict to succeed him as chair of Columbia's anthropology department, but she was sidelined in favor of Ralph Linton,[17] and Mead was limited to her offices at the AMNH.[18]  |

クローバー、ミード、ベネディクト ボアズはコロンビア大学とアメリカ自然史博物館(AMNH)での地位を利用して、何世代にもわたる学生を育成した。彼の最初の世代の学生には、アルフレッ ド・クローバー、ロバート・ローウィ、エドワード・サピア、ルース・ベネディクトが含まれ、それぞれが北米先住民文化に関する詳細な研究を生み出した。彼 らは単一の進化過程という理論を攻撃するために用いられた豊富な詳細を提供した。クローバーとサピアがネイティブアメリカンの言語に焦点を当てたことは、 言語学を真に普遍的な科学として確立し、インド・ヨーロッパ語族への歴史的偏重から解放するのに貢献した。 アルフレッド・クローバーの教科書『人類学』(1923年)の出版は、アメリカ人類学における転換点となった。30年にわたる資料収集の後、ボアズ学派は 一般化への強い衝動を感じた。これはマーガレット・ミードやルース・ベネディクトといった若手ボアズ学派による「文化と人格」研究で最も顕著だった。ジー クムント・フロイトやカール・ユングら精神分析心理学者の影響を受けたこれらの研究者は、個人が育った広範な文化的・社会的力によって人格が形成される過 程を理解しようとした。  ミードの『サモアの思春期』(1928年)やベネディクトの『菊と刀』(1946年)といった著作は今もアメリカで人気があるが、ミードとベネディクトは 人類学という学問分野に、一部が期待したほどの影響力を及ぼすことはなかった。ボアズはルース・ベネディクトをコロンビア大学人類学部長の後継者に据える 計画を立てていたが、彼女はラルフ・リントンに取って代わられ[17]、ミードはアメリカ自然史博物館(AMNH)の職に留まることとなった[18]。  |

| Wolf, Sahlins, Mintz, and political economy Main articles: Political economy in anthropology, Eric Wolf, Marshall Sahlins, and Sidney Mintz In the 1950s and mid-1960s anthropology tended increasingly to model itself after the natural sciences. Some anthropologists, such as Lloyd Fallers and Clifford Geertz, focused on processes of modernization by which newly independent states could develop. Others, such as Julian Steward and Leslie White, focused on how societies evolve and fit their ecological niche—an approach popularized by Marvin Harris. Economic anthropology as influenced by Karl Polanyi and practiced by Marshall Sahlins and George Dalton challenged standard neoclassical economics to take account of cultural and social factors and employed Marxian analysis into anthropological study. In England, British Social Anthropology's paradigm began to fragment as Max Gluckman and Peter Worsley experimented with Marxism and authors such as Rodney Needham and Edmund Leach incorporated Lévi-Strauss's structuralism into their work. Structuralism also influenced a number of developments in the 1960s and 1970s, including cognitive anthropology and componential analysis. In keeping with the times, much of anthropology became politicized through the Algerian War of Independence and opposition to the Vietnam War;[19] Marxism became an increasingly popular theoretical approach in the discipline.[20] By the 1970s the authors of volumes such as Reinventing Anthropology worried about anthropology's relevance. Since the 1980s issues of power, such as those examined in Eric Wolf's Europe and the People Without History, have been central to the discipline. In the 1980s books like Anthropology and the Colonial Encounter pondered anthropology's ties to colonial inequality, while the immense popularity of theorists such as Antonio Gramsci and Michel Foucault moved issues of power and hegemony into the spotlight. Gender and sexuality became popular topics, as did the relationship between history and anthropology, influenced by Marshall Sahlins, who drew on Lévi-Strauss and Fernand Braudel to examine the relationship between symbolic meaning, sociocultural structure, and individual agency in the processes of historical transformation. Jean and John Comaroff produced a whole generation of anthropologists at the University of Chicago that focused on these themes. Also influential in these issues were Nietzsche, Heidegger, the critical theory of the Frankfurt School, Derrida and Lacan.[21] |

ウルフ、サーリンズ、ミンツ、そして政治経済学 主な記事:人類学における政治経済学、エリック・ウルフ、マーシャル・サーリンズ、シドニー・ミンツ 1950年代から1960年代半ばにかけて、人類学は次第に自然科学の手法を模倣する傾向が強まった。ロイド・ファラーズやクリフォード・ギアーツといっ た人類学者は、新たに独立した国家が発展するための近代化プロセスに焦点を当てた。ジュリアン・スチュワートやレスリー・ホワイトらは、社会がどのように 進化し生態的ニッチに適応するかに焦点を当てた。このアプローチはマービン・ハリスによって普及した。 カール・ポラニーの影響を受け、マーシャル・サリンズやジョージ・ダルトンによって実践された経済人類学は、文化・社会的要因を考慮に入れるよう新古典派 経済学の標準理論に異議を唱え、人類学的研究にマルクス主義的分析を導入した。イギリスでは、マックス・グルックマンやピーター・ウォースリーがマルクス 主義を実験的に取り入れ、ロドニー・ニーダムやエドマンド・リーチらがレヴィ=ストロースの構造主義を研究に組み込むなど、英国社会人類学のパラダイムが 分断され始めた。構造主義は1960~70年代の認知人類学や構成要素分析など、多くの発展にも影響を与えた。 時代を反映し、アルジェリア独立戦争やベトナム戦争反対運動を通じて人類学の多くは政治化された[19]。マルクス主義はこの分野でますます人気のある理 論的アプローチとなった[20]。1970年代までに『人類学の再発明』などの著作の著者たちは、人類学の関連性について懸念を抱くようになった。 1980年代以降、エリック・ウルフの『ヨーロッパと歴史を持たない人々』で考察されたような権力の問題が学問の中心となった。1980年代には『人類学 と植民地遭遇』のような書籍が人類学と植民地的不平等との結びつきを考察し、アントニオ・グラムシやミシェル・フーコーといった理論家の爆発的人気が権力 とヘゲモニーの問題を脚光に押し上げた。ジェンダーとセクシュアリティが人気テーマとなったのと同様に、歴史と人類学の関係も注目を集めた。これはマー シャル・サリンズの影響によるもので、彼はレヴィ=ストロースとフェルナン・ブローデルを参照し、歴史的変容の過程における象徴的意味、社会文化的構造、 個人の主体性の関係を考察した。シカゴ大学ではジャン・コマロフとジョン・コマロフが、こうしたテーマに焦点を当てた人類学者たちを一世代にわたり育成し た。ニーチェ、ハイデガー、フランクフルト学派の批判理論、デリダ、ラカンもまた、これらの問題において影響力を持っていた。 |

| Geertz, Schneider, and interpretive anthropology Main articles: Clifford Geertz and David M. Schneider Many anthropologists reacted against the renewed emphasis on materialism and scientific modelling derived from Marx by emphasizing the importance of the concept of culture. Authors such as David Schneider, Clifford Geertz, and Marshall Sahlins developed a more fleshed-out concept of culture as a web of meaning or signification, which proved very popular within and beyond the discipline. Geertz was to state: Believing, with Max Weber, that man is an animal suspended in webs of significance he himself has spun, I take culture to be those webs, and the analysis of it to be therefore not an experimental science in search of law but an interpretive one in search of meaning. — Clifford Geertz (1973)[22] Geertz's interpretive method involved what he called "thick description". The cultural symbols of rituals, political and economic action, and of kinship, are "read" by the anthropologist as if they are a document in a foreign language. The interpretation of those symbols must be re-framed for their anthropological audience, i.e. transformed from the "experience-near" but foreign concepts of the other culture, into the "experience-distant" theoretical concepts of the anthropologist. These interpretations must then be reflected back to its originators, and its adequacy as a translation fine-tuned in a repeated way, a process called the hermeneutic circle. Geertz applied his method in a number of areas, creating programs of study that were very productive. His analysis of "religion as a cultural system" was particularly influential outside of anthropology. David Schnieder's cultural analysis of American kinship has proven equally influential.[23] Schneider demonstrated that the American folk-cultural emphasis on "blood connections" had an undue influence on anthropological kinship theories, and that kinship is not a biological characteristic, but a cultural relationship established on very different terms in different societies.[24] Prominent British symbolic anthropologists include Victor Turner and Mary Douglas. |

ギアーツ、シュナイダー、解釈人類学 主な記事:クリフォード・ギアーツとデイヴィッド・M・シュナイダー 多くの人類学者は、マルクスに由来する唯物論と科学的モデリングの重視が再び高まったことに対して、文化の概念の重要性を強調することで反発した。デビッ ド・シュナイダー、クリフォード・ギアーツ、マーシャル・サリンズなどの著者は、文化を意味や表象の網としてより具体化した概念を開発し、それはこの分野 の内外で非常に人気を博した。ギアーツは次のように述べている。 マックス・ヴェーバーと同様に、人間は自ら紡いだ意味の網に懸けられた動物であると信じている私は、文化をその網と捉え、その分析は法則を求める実験科学ではなく、意味を求める解釈学であると考える。 — クリフォード・ギアーツ (1973)[22] ギアーツの解釈方法は、彼が「濃厚な記述」と呼んだものを含む。儀礼、政治的・経済的行動、親族関係といった文化的象徴は、人類学者によって、あたかも外 国語の文書であるかのように「読まれる」。それらの象徴の解釈は、人類学の聴衆のために再構成されなければならない。つまり、他文化の「経験に近い」が外 国の概念から、人類学者の「経験から遠い」理論的概念へと変換される。これらの解釈はその後、その創始者たちに反映され、翻訳としての妥当性が繰り返し微 調整される。このプロセスは解釈学の循環と呼ばれる。ギアーツはこの手法を多くの分野に応用し、非常に生産的な研究プログラムを創出した。「文化システム としての宗教」に関する彼の分析は、人類学の枠を超えて特に影響力があった。デビッド・シュナイダーによるアメリカの親族関係に関する文化分析も、同様に 影響力があることが証明されている[23]。シュナイダーは、アメリカの民俗文化が「血縁」を重視することが人類学の親族関係理論に過大な影響を与えてい ること、そして親族関係は生物学的特徴ではなく、社会によって大きく異なる条件に基づいて確立される文化的関係であることを示した[24]。 英国の著名な象徴人類学者としては、ヴィクター・ターナーやメアリー・ダグラスが挙げられる。 |

| The post-modern turn In the late 1980s and 1990s authors such as James Clifford pondered ethnographic authority, in particular how and why anthropological knowledge was possible and authoritative. They were reflecting trends in research and discourse initiated by feminists in the academy, although they excused themselves from commenting specifically on those pioneering critics.[25] Nevertheless, key aspects of feminist theory and methods became de rigueur as part of the 'post-modern moment' in anthropology: Ethnographies became more interpretative and reflexive,[26] explicitly addressing the author's methodology; cultural, gendered, and racial positioning; and their influence on the ethnographic analysis. This was part of a more general trend of postmodernism that was popular contemporaneously.[27] Currently anthropologists pay attention to a wide variety of issues pertaining to the contemporary world, including globalization, medicine and biotechnology, indigenous rights, virtual communities, and the anthropology of industrialized societies. |

ポストモダンの転換 1980年代後半から1990年代にかけて、ジェームズ・クリフォードら研究者は民族誌的権威、特に人類学的知識が如何にして可能となり権威を持つのかを 考察した。彼らは学界のフェミニストたちが始めた研究と言説の潮流を反映していたが、それらの先駆的批評家たちについて具体的に論じることは避けた。 [25] しかしながら、フェミニスト理論と方法論の核心的側面は、人類学における「ポストモダンの瞬間」の一部として必須の要素となった。民族誌はより解釈的かつ 反省的になり[26]、著者の方法論、文化的・ジェンダー的・人種的立場、そしてそれらが民族誌的分析に及ぼす影響を明示的に扱うようになった。これは当 時流行したポストモダニズムのより一般的な潮流の一部であった[27]。現在、人類学者はグローバル化、医学とバイオテクノロジー、先住民族の権利、仮想 コミュニティ、工業化社会の人類学など、現代世界に関わる多様な問題に注目している。 |

| Socio-cultural anthropology subfields Anthropology of art Cognitive anthropology Anthropology of development Disability anthropology Ecological anthropology Economic anthropology Ethnomusicology Feminist anthropology and anthropology of gender and sexuality Ethnohistory and historical anthropology Kinship and family Legal anthropology Multimodal anthropology Media anthropology Medical anthropology Political anthropology Political economy in anthropology Psychological anthropology Public anthropology Anthropology of religion Cyborg anthropology Transpersonal anthropology Urban anthropology Visual anthropology |

社会文化人類学のサブ分野 芸術人類学 認知人類学 開発人類学 障害人類学 生態人類学 経済人類学 民族音楽学 フェミニスト人類学およびジェンダー・セクシュアリティ人類学 民族歴史学および歴史人類学 親族と家族 法人類学 マルチモーダル人類学 メディア人類学 医療人類学 政治人類学 人類学における政治経済学 心理人類学 公共人類学 宗教人類学 サイボーグ人類学 トランスパーソナル人類学 都市人類学 視覚人類学 |

| Methods Modern cultural anthropology has its origins in, and developed in reaction to, 19th century ethnology, which involves the organized comparison of human societies. Scholars like E.B. Tylor and J.G. Frazer in England worked mostly with materials collected by others—usually missionaries, traders, explorers, or colonial officials—earning them the moniker of "arm-chair anthropologists". |

方法論 現代文化人類学は、19世紀の民族学に起源を持ち、それに反発して発展した。民族学とは人間社会の体系的な比較を扱う学問である。イギリスのE.B.タイ ラーやJ.G.フレイザーといった学者たちは、主に他者(通常は宣教師、商人、探検家、植民地官吏)が収集した資料を用いて研究したため、「机上の人類学 者」というあだ名で呼ばれた。 |

| Participant observation Main article: Participant observation Participant observation is one of the principal research methods of cultural anthropology. It relies on the assumption that the best way to understand a group of people is to interact with them closely over a long period of time.[28] The method originated in the field research of social anthropologists, especially Bronislaw Malinowski in Britain, the students of Franz Boas in the United States, and in the later urban research of the Chicago School of Sociology. Historically, the group of people being studied was a small, non-Western society. However, today it may be a specific corporation, a church group, a sports team, or a small town.[28] There are no restrictions as to what the subject of participant observation can be, as long as the group of people is studied intimately by the observing anthropologist over a long period of time. This allows the anthropologist to develop trusting relationships with the subjects of study and receive an inside perspective on the culture, which helps him or her to give a richer description when writing about the culture later. Observable details (like daily time allotment) and more hidden details (like taboo behavior) are more easily observed and interpreted over a longer period of time, and researchers can discover discrepancies between what participants say—and often believe—should happen (the formal system) and what actually does happen, or between different aspects of the formal system; in contrast, a one-time survey of people's answers to a set of questions might be quite consistent, but is less likely to show conflicts between different aspects of the social system or between conscious representations and behavior.[29] Interactions between an ethnographer and a cultural informant must go both ways.[30] Just as an ethnographer may be naive or curious about a culture, the members of that culture may be curious about the ethnographer. To establish connections that will eventually lead to a better understanding of the cultural context of a situation, an anthropologist must be open to becoming part of the group, and willing to develop meaningful relationships with its members.[28] One way to do this is to find a small area of common experience between an anthropologist and their subjects, and then to expand from this common ground into the larger area of difference.[31] Once a single connection has been established, it becomes easier to integrate into the community, and it is more likely that accurate and complete information is being shared with the anthropologist. Before participant observation can begin, an anthropologist must choose both a location and a focus of study.[28] This focus may change once the anthropologist is actively observing the chosen group of people, but having an idea of what one wants to study before beginning fieldwork allows an anthropologist to spend time researching background information on their topic. It can also be helpful to know what previous research has been conducted in one's chosen location or on similar topics, and if the participant observation takes place in a location where the spoken language is not one the anthropologist is familiar with, they will usually also learn that language. This allows the anthropologist to become better established in the community. The lack of need for a translator makes communication more direct, and allows the anthropologist to give a richer, more contextualized representation of what they witness. In addition, participant observation often requires permits from governments and research institutions in the area of study, and always needs some form of funding.[28] The majority of participant observation is based on conversation. This can take the form of casual, friendly dialogue, or can also be a series of more structured interviews. A combination of the two is often used, sometimes along with photography, mapping, artifact collection, and various other methods.[28] In some cases, ethnographers also turn to structured observation, in which an anthropologist's observations are directed by a specific set of questions they are trying to answer.[32] In the case of structured observation, an observer might be required to record the order of a series of events, or describe a certain part of the surrounding environment.[32] While the anthropologist still makes an effort to become integrated into the group they are studying, and still participates in the events as they observe, structured observation is more directed and specific than participant observation in general. This helps to standardize the method of study when ethnographic data is being compared across several groups or is needed to fulfill a specific purpose, such as research for a governmental policy decision. One common criticism of participant observation is its lack of objectivity.[28] Because each anthropologist has their own background and set of experiences, each individual is likely to interpret the same culture in a different way. Who the ethnographer is has a lot to do with what they will eventually write about a culture, because each researcher is influenced by their own perspective.[33] This is considered a problem especially when anthropologists write in the ethnographic present, a present tense which makes a culture seem stuck in time, and ignores the fact that it may have interacted with other cultures or gradually evolved since the anthropologist made observations.[28] To avoid this, past ethnographers have advocated for strict training, or for anthropologists working in teams. However, these approaches have not generally been successful, and modern ethnographers often choose to include their personal experiences and possible biases in their writing instead.[28] Participant observation has also raised ethical questions, since an anthropologist is in control of what they report about a culture. In terms of representation, an anthropologist has greater power than their subjects of study, and this has drawn criticism of participant observation in general.[28] Additionally, anthropologists have struggled with the effect their presence has on a culture. Simply by being present, a researcher causes changes in a culture, and anthropologists continue to question whether or not it is appropriate to influence the cultures they study, or possible to avoid having influence.[28] |

参与観察 メイン記事: 参与観察 参与観察は文化人類学の主要な研究手法の一つである。これは、ある集団を理解する最良の方法は、長期間にわたり密接に交流することだという前提に基づいて いる。[28] この手法は社会人類学者のフィールドワーク、特に英国のブロニスワフ・マリーノフスキー、米国のフランツ・ボアズの弟子たち、そして後のシカゴ学派の都市 研究に起源を持つ。歴史的には、研究対象となる集団は小規模な非西洋社会であった。しかし今日では、特定の企業、教会グループ、スポーツチーム、あるいは 小さな町などが対象となり得る。[28] 参与観察の対象となるものには制限がない。ただし、観察する人類学者が長期間にわたり対象集団を密接に研究することが条件である。これにより人類学者は研 究対象者と信頼関係を築き、文化に対する内部の視点を得られる。これは後に文化について記述する際、より豊かな描写を可能にする。観察可能な詳細(日常の 時間配分など)やより隠れた詳細(タブー行為など)は、長期間にわたって観察・解釈しやすくなる。研究者は、参加者が言うこと(そして往々にして信じてい ること)と実際に起きることの間の不一致、あるいは形式的な制度の異なる側面間の不一致を発見できる。一方、特定の質問に対する人民の回答を一回限りで調 査した場合、回答はかなり一貫しているかもしれないが、社会システムの異なる側面間や、意識的な表象と行動の間の矛盾を示す可能性は低くなる。[29] エスノグラファーと文化情報提供者との相互作用は双方向でなければならない[30]。研究者が文化に対して素朴な好奇心を持つのと同様に、その文化の成員 もエスノグラファーに興味を持つことがある。状況の文化的文脈をより深く理解するための繋がりを築くには、人類学者は集団の一員となることに開かれ、成員 との有意義な関係を築く意思を持たねばならない。[28] その方法の一つは、人類学者と対象者の間に存在する小さな共通体験の領域を見つけ、そこから共通基盤を広げて差異のより大きな領域へと進み出すことだ。 [31] 一度つながりが築かれれば、コミュニティへの統合は容易になり、人類学者に対して正確で完全な情報が共有される可能性が高まる. 参与観察を始める前に、人類学者は調査場所と研究対象の両方を選ばねばならない。[28] この焦点は、人類学者が選んだ集団を実際に観察し始めてから変わることもあるが、フィールドワークを始める前に何を研究したいかの方向性を持つことで、人 類学者はテーマに関する背景情報を調べる時間を確保できる。また、選択した場所や類似テーマで過去に実施された研究を把握しておくことも有益である。参与 観察が人類学者が不慣れな言語が話される地域で行われる場合、通常はその言語も習得する。これにより人類学者はコミュニティ内での立場をより確固たるもの にできる。通訳が不要なためコミュニケーションが直接的になり、観察した事象をより豊かで文脈に沿った形で表現できる。加えて、参与観察には研究地域の政 府や研究機関からの許可が必要となる場合が多く、常に何らかの資金調達が必要だ。 参与観察の大半は会話に基づいている。これは気軽な友好的な対話の形をとることもあれば、より構造化された一連のインタビューの形をとることもある。両者 を組み合わせた方法がよく用いられ、時には写真撮影、地図作成、遺物収集、その他様々な方法が併用される。[28] 場合によっては、エスノグラファーは構造化観察にも頼る。これは人類学者の観察が、答えようとしている特定の質問群によって導かれる方法である。[32] 構造化された観察では、観察者は一連の出来事の順序を記録したり、周囲の環境の特定部分を記述したりすることが求められる。[32] 構造化された観察においても、人類学者は研究対象の集団に溶け込む努力を続け、観察しながら出来事に参加するが、一般的な参与観察よりも指向性が強く具体 的である。これは、複数の集団間で民族誌的データを比較する場合や、政府の政策決定のための研究など特定の目的を達成するために必要な場合、研究方法を標 準化するのに役立つ。 参与観察に対する一般的な批判の一つは、客観性の欠如である。[28] 各エスノグラファーは独自の背景と経験の集合体を持つため、同じ文化を異なる方法で解釈する可能性が高い。エスノグラファーが誰であるかは、最終的にその 文化について何を書くかに大きく関わる。各研究者は自身の視点に影響されるからだ[33]。これは特に、人類学者が民族誌的現在形 (ethnographic present)で記述する場合に問題となる。この現在形は文化を時間的に固定されたように見せ、人類学者が観察を行って以来、他の文化と交流したり徐々 に変化したりした可能性を無視する。[28] この問題を回避するため、過去のエスノグラファーは厳格な訓練やチームでの研究を提唱してきた。しかしこれらの手法は概して成功せず、現代のエスノグラ ファーはむしろ個人的な経験や潜在的な偏見を記述に含めることを選ぶことが多い。[28] 参与観察は倫理的問題も提起している。なぜなら人類学者が文化について報告する内容を制御できるからだ。表現の観点では、人類学者は研究対象よりも大きな 権力を持つため、参与観察全般に対する批判が寄せられている。[28] さらに人類学者は、自身の存在が文化に与える影響にも苦慮してきた。研究者が単に存在すること自体が文化に変化をもたらすため、研究対象の文化に影響を与 えることが適切かどうか、あるいは影響を完全に回避できるかどうかについて、人類学者は今も問い続けている。[28] |

| Ethnography Main article: Ethnography In the 20th century, most cultural and social anthropologists turned to the crafting of ethnographies. An ethnography is a piece of writing about a people, at a particular place and time. Typically, the anthropologist lives among people in another society for a period of time, simultaneously participating in and observing the social and cultural life of the group. Numerous other ethnographic techniques have resulted in ethnographic writing or details being preserved, as cultural anthropologists also curate materials, spend long hours in libraries, churches and schools poring over records, investigate graveyards, and decipher ancient scripts. A typical ethnography will also include information about physical geography, climate and habitat. It is meant to be a holistic piece of writing about the people in question, and today often includes the longest possible timeline of past events that the ethnographer can obtain through primary and secondary research. Bronisław Malinowski developed the ethnographic method, and Franz Boas taught it in the United States. Boas' students such as Alfred L. Kroeber, Ruth Benedict and Margaret Mead drew on his conception of culture and cultural relativism to develop cultural anthropology in the United States. Simultaneously, Malinowski and A.R. Radcliffe Brown's students were developing social anthropology in the United Kingdom. Whereas cultural anthropology focused on symbols and values, social anthropology focused on social groups and institutions. Today socio-cultural anthropologists attend to all these elements. In the early 20th century, socio-cultural anthropology developed in different forms in Europe and in the United States. European "social anthropologists" focused on observed social behaviors and on "social structure", that is, on relationships among social roles (for example, husband and wife, or parent and child) and social institutions (for example, religion, economy, and politics). American "cultural anthropologists" focused on the ways people expressed their view of themselves and their world, especially in symbolic forms, such as art and myths. These two approaches frequently converged and generally complemented one another. For example, kinship and leadership function both as symbolic systems and as social institutions. Today almost all socio-cultural anthropologists refer to the work of both sets of predecessors and have an equal interest in what people do and in what people say. |

民族誌(エスノグラフィー) 主な記事: 民族誌 20世紀には、ほとんどの文化人類学者や社会人類学者が民族誌の作成に注力した。民族誌とは、特定の場所と時間における人々の生活を描いた著作である。通常、人類学者は一定期間、他社会の集団の中に身を置き、その集団の社会・文化的生活に参加しつつ観察する。 その他にも数多くの民族誌的手法が民族誌的記述や詳細の保存につながっている。エスノグラファーは資料を収集し、図書館や教会、学校で記録を丹念に調べ、 墓地を調査し、古代文字を解読するため、長時間を費やすのである。典型的な民族誌には、自然地理、気候、生息環境に関する情報も含まれる。対象となる人々 についての包括的な記述を意図しており、現代ではエスノグラファーが一次・二次調査を通じて入手可能な限り最長の過去の出来事の年表を盛り込むことが多 い。 ブロニスワフ・マリンスキが民族誌的手法を発展させ、フランツ・ボアズが米国でこれを教えた。アルフレッド・L・クローバー、ルース・ベネディクト、マー ガレット・ミードといったボアズの弟子たちは、彼の文化観と文化的相対主義を基に、アメリカで文化人類学を発展させた。同時に、マリンノフスキーとA・ R・ラドクリフ=ブラウンの弟子たちは、イギリスで社会人類学を発展させていた。文化人類学が象徴や価値観に焦点を当てたのに対し、社会人類学は社会集団 や制度に焦点を当てた。今日では社会文化人類学者がこれら全ての要素を扱う。 20世紀初頭、社会文化人類学はヨーロッパとアメリカで異なる形で発展した。ヨーロッパの「社会人類学者」は観察された社会的行動と「社会構造」、すなわち社会的役割(例えば夫婦や親子)と社会制度(例えば宗教、経済、政治)間の関係に焦点を当てた。 一方、アメリカの「文化人類学者」は、人民が自己や世界に対する認識を表現する方法、特に芸術や神話といった象徴的形態に焦点を当てた。この二つのアプ ローチは頻繁に融合し、互いに補完し合うことが多かった。例えば、親族関係や指導者機能は、象徴的システムとして機能すると同時に社会制度としても機能す る。今日では、ほぼ全ての社会文化人類学者が両方の先駆者の業績を参照し、人民の行動と人民の発言の両方に等しく関心を持っている。 |

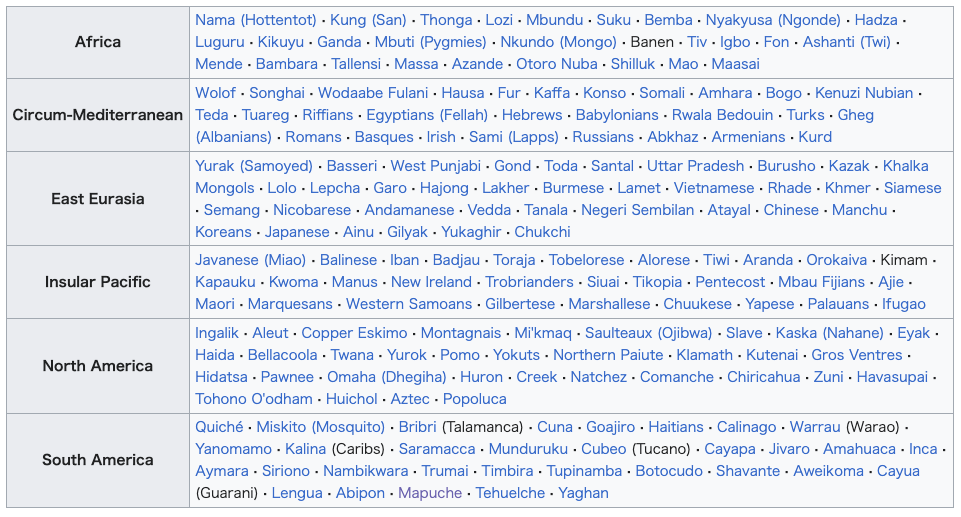

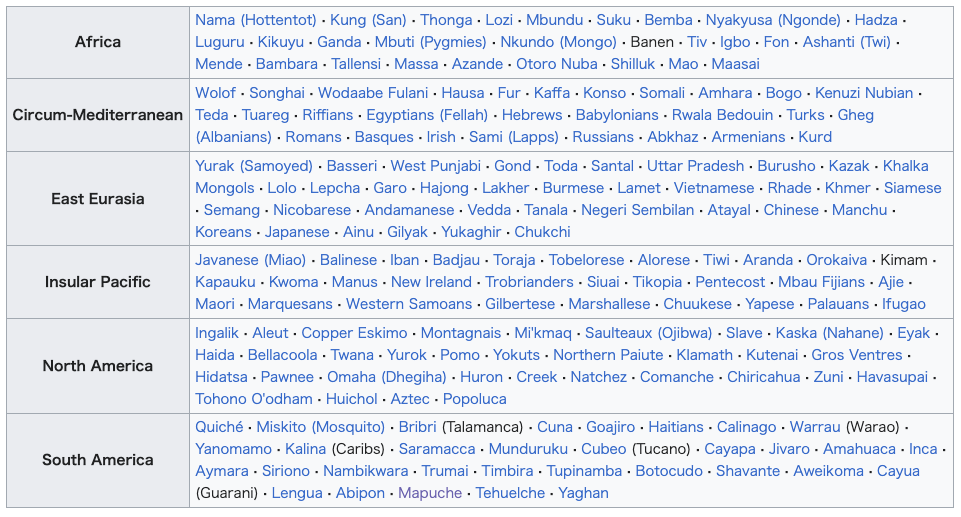

| Cross-cultural comparison One means by which anthropologists combat ethnocentrism is to engage in the process of cross-cultural comparison. It is important to test so-called "human universals" against the ethnographic record. Monogamy, for example, is frequently touted as a universal human trait, yet comparative study shows that it is not. The Human Relations Area Files, Inc. (HRAF) is a research agency based at Yale University. Since 1949, its mission has been to encourage and facilitate worldwide comparative studies of human culture, society, and behavior in the past and present. The name came from the Institute of Human Relations, an interdisciplinary program/building at Yale at the time. The Institute of Human Relations had sponsored HRAF's precursor, the Cross-Cultural Survey (see George Peter Murdock), as part of an effort to develop an integrated science of human behavior and culture. The two eHRAF databases on the Web are expanded and updated annually. eHRAF World Cultures includes materials on cultures, past and present, and covers nearly 400 cultures. The second database, eHRAF Archaeology, covers major archaeological traditions and many more sub-traditions and sites around the world. Comparison across cultures includes the industrialized (or de-industrialized) West. Cultures in the more traditional standard cross-cultural sample of small-scale societies are: |

異文化比較 人類学者が民族中心主義と戦う一つの手段は、異文化比較のプロセスに取り組むことだ。いわゆる「人類の普遍性」を民族誌的記録と照らし合わせて検証するこ とが重要である。例えば一夫一婦制はしばしば普遍的人類的特性として喧伝されるが、比較研究によればそうではない。ヒューマン・リレーションズ・エリア・ ファイルズ社(HRAF)はイェール大学に拠点を置く研究機関である。1949 年以降、同機関の使命は過去と現在の人類の文化・社会・行動に関する世界的な比較研究を促進・支援することにある。名称は当時イェール大学に存在した学際 的プログラム/施設「人間関係研究所」に由来する。同研究所は人類行動と文化の統合的科学構築の一環として、HRAFの前身である「異文化調査」(ジョー ジ・ピーター・マードック参照)を後援していた。ウェブ上の2つのeHRAFデータベースは毎年拡充・更新されている。eHRAF World Culturesは過去と現在の文化に関する資料を含み、約400の文化を網羅する。もう一つのデータベースeHRAF Archaeologyは主要な考古学的伝統と、さらに多くのサブ伝統や世界中の遺跡を扱う。 文化間比較の対象には、工業化(あるいは脱工業化)された西洋社会も含まれる。より伝統的な小規模社会からなる標準的な比較文化サンプルに含まれる文化は次の通りである: |

|

|

| Africa |

アフリカ(注意:このリストは文化のカタログはe-HRAFの恣意的リストであり世界文化のサンプリングではない) |

| Nama (Hottentot) Kung (San) Thonga Lozi Mbundu Suku Bemba Nyakyusa (Ngonde) Hadza Luguru Kikuyu Ganda Mbuti (Pygmies) Nkundo (Mongo) Banen TivIgbo Fon Ashanti (Twi) Mende Bambara Tallensi Massa Azande Otoro Nuba Shilluk Mao Maasai |

ナマ(ホッテントット族) クング(サン族) トンガ ロジ ムブンドゥ スク ベンバ ニャキュサ(ンゴンデ族) ハザ ルグル キクユ ガンダ ムブティ(ピグミー族) ンクンド(モンゴ族) バネン族 ティヴ族イボ族 フォン族 アシャンティ族(トゥイ族) メンデ族 バンバラ族 タレンシ族 マッサ族 アザンデ族 オトロ族 ヌバ族 シルック族 マオ族 マサイ族 |

| Circum-Mediterranean |

環地中海(広域) |

| Wolof Songhai Wodaabe Fulani Hausa FurKaffa Konso Somali Amhara Bogo Kenuzi Nubian Teda Tuareg Riffians Egyptians (Fellah) Hebrews Babylonians Rwala Bedouin Turks Gheg (Albanians) Romans Basques Irish Sami (Lapps) Russians Abkhaz Armenians Kurd |

ウォロフ族 ソンガイ族 ウォダベ族 フラニ族 ハウサ族 フル族カッファ族 コンソ族 ソマリ族 アムハラ族 ボゴ族 ケヌジ族 ヌビア族 テダ族 トゥアレグ族 リフィアン族 エジプト人(フェラー) ヘブライ人 バビロニア人 ルワラ ベドウィン トルコ人 ゲグ(アルバニア人) ローマ人 バスク人 アイルランド人 サーミ(ラップ人) ロシア人 アブハズ人 アルメニア人 クルド人 |

| East Eurasia |

東ユーラシア |

| Yurak (Samoyed) Basseri West Punjabi Gond Toda Santal Uttar Pradesh Burusho Kazak Khalka Mongols Lolo Lepcha Garo Hajong Lakher Burmese Lamet Vietnamese Rhade Khmer Siamese Semang Nicobarese Andamanese Vedda Tanala Negeri Sembilan Atayal Chinese Manchu Koreans Japanese Ainu Gilyak Yukaghir Chukchi |

ユラク(サモエド) バセリ 西 パンジャーブ ゴンド トダ サンタル ウッタール プラデーシュ ブルショ カザク ハルカ・モンゴル ロロ レプチャ ガロ ハジョン族 ラケル族 ビルマ族 ラメット族 ベトナム族 ラーデ族 クメール族 シャム族 セマン族 ニコバル族 アンダマン族 ヴェッダ族 タナラ族 ネゲリ族 センビラン族 アタヤル族 中国族 満州族 韓国族 日本族 アイヌ族 ギリヤク族 ユカギル族 チュクチ族 |

| Insular Pacific |

島嶼部・太平洋 |

| Javanese(Miao) Balinese Iban Badjau Toraja Tobelorese Alorese Tiwi Aranda Orokaiva Kimam Kapauku Kwoma Manus New Ireland Trobrianders Siuai Tikopia Pentecost Mbau Fijians Ajie Maori Marquesans Western Samoans Gilbertese Marshallese Chuukese Yapese Palauans Ifugao |

ジャワ人(ミャオ族) バリ人 イバン族 バジャウ族 トラージャ族 トベロ族 アロル族 ティウィ族 アランダ族 オロカイバ族 キマム族 カパウク族 クワマ族 マヌス族 ニューアイルランド トロブリアンド人 シウアイ ティコピア ペンテコスト ムバウ フィジー人 アジー マオリ マルケサス 西部 サモア人 ギルバート人 マーシャル人 チューク人 ヤップ人 パラオ人 イフガオ |

| North America |

北アメリカ |

| Ingalik Aleut Copper Eskimo Montagnais Mi'kmaq Saulteaux (Ojibwa) SlaveKaska (Nahane) Eyak Haida Bellacoola Twana Yurok Pomo Yokuts Northern Paiute Klamath Kutenai Gros Ventres Hidatsa Pawnee Omaha (Dhegiha) Huron Creek Natchez Comanche Chiricahua Zuni Havasupai Tohono O'odham Huichol Aztec Popoluca |

インガリク アレウト カッパー エスキモー モンタニェ ミクマク ソルトー(オジブワ) スレイブカスカ(ナハネ) エイヤック ハイダ ベラクーラ トゥワナ ユロック ポモ ヨクツ族 北部パイユート族 クラマス族 クテナイ族 グロ・ベントル族 ヒダツァ族 ポーニー族 オマハ族(デギハ族) ヒューロン族 クリーク族 ナチェズ族 コマンチ族 チリカウア族 ズニ族 ハバスパイ族 トホノ族 オードハム族 ウィチョル族 アステカ族 ポポルカ族 |

| South America |

南アメリカ |

| Quiché Miskito (Mosquito) Bribri (Talamanca) Cuna Goajiro Haitians Calinago Warrau (Warao) Yanomamo Kalina (Caribs) Saramacca Munduruku Cubeo(Tucano) Cayapa Jivaro AmahuacaInca Aymara Siriono Nambikwara Trumai Timbira Tupinamba Botocudo Shavante Aweikoma Cayua (Guarani) Lengua Abipon Mapuche Tehuelche Yaghan |

キチェ族 ミスキート族(モスキート族) ブリブリ族(タラマンカ族) クナ族 ゴアヒロ族 ハイチ人 カリナゴ族 ワラウ族(ワラオ族) ヤノマモ族 カリナ族(カリブ族) サラマカ族 ムンドゥルク族 クベオ族(トゥカーノ族) カヤパ ヒバロ アマワカインカ アイマラ シリオノ ナンビクワラ トルマイ ティンビラ トゥピナンバ ボトクド シャバンテ アウェイコマ カユア (グアラニ) レンガ アビポン マプチェ テウェルチェ ヤガン |

| Multi-sited ethnography Ethnography dominates socio-cultural anthropology. Nevertheless, many contemporary socio-cultural anthropologists have rejected earlier models of ethnography as treating local cultures as bounded and isolated. These anthropologists continue to concern themselves with the distinct ways people in different locales experience and understand their lives, but they often argue that one cannot understand these particular ways of life solely from a local perspective; they instead combine a focus on the local with an effort to grasp larger political, economic, and cultural frameworks that impact local lived realities. Notable proponents of this approach include Arjun Appadurai, James Clifford, George Marcus, Sidney Mintz, Michael Taussig, Eric Wolf and Ronald Daus. A growing trend in anthropological research and analysis is the use of multi-sited ethnography, discussed in George Marcus' article, "Ethnography In/Of the World System: the Emergence of Multi-Sited Ethnography". Looking at culture as embedded in macro-constructions of a global social order, multi-sited ethnography uses traditional methodology in various locations both spatially and temporally. Through this methodology, greater insight can be gained when examining the impact of world-systems on local and global communities. Also emerging in multi-sited ethnography are greater interdisciplinary approaches to fieldwork, bringing in methods from cultural studies, media studies, science and technology studies, and others. In multi-sited ethnography, research tracks a subject across spatial and temporal boundaries. For example, a multi-sited ethnography may follow a "thing", such as a particular commodity, as it is transported through the networks of global capitalism. Multi-sited ethnography may also follow ethnic groups in diaspora, stories or rumours that appear in multiple locations and in multiple time periods, metaphors that appear in multiple ethnographic locations, or the biographies of individual people or groups as they move through space and time. It may also follow conflicts that transcend boundaries. An example of multi-sited ethnography is Nancy Scheper-Hughes' work on the international black market for the trade of human organs. In this research, she follows organs as they are transferred through various legal and illegal networks of capitalism, as well as the rumours and urban legends that circulate in impoverished communities about child kidnapping and organ theft. Sociocultural anthropologists have increasingly turned their investigative eye on to "Western" culture. For example, Philippe Bourgois won the Margaret Mead Award in 1997 for In Search of Respect, a study of the entrepreneurs in a Harlem crack-den. Also growing more popular are ethnographies of professional communities, such as laboratory researchers, Wall Street investors, law firms, or information technology (IT) computer employees.[34] |

複数地点民族誌(マルチサイト・エスノグラフィー) 民族誌は社会文化人類学において支配的である。しかしながら、多くの現代の社会文化人類学者は、現地文化を境界のある孤立したものと扱う従来の民族誌モデ ルを拒否している。これらの人類学者は、異なる地域の人々が自らの生活を経験し理解する独特の様式に関心を持ち続けるが、そうした特定の生活様式を現地の 視点のみから理解することは不可能だと主張することが多い。代わりに、現地への焦点を維持しつつ、現地の生活実態に影響を与えるより大きな政治的・経済 的・文化的枠組みを把握しようとする努力を組み合わせるのである。このアプローチの代表的な提唱者には、アルジュン・アッパドゥライ、ジェームズ・クリ フォード、ジョージ・マーカス、シドニー・ミンツ、マイケル・タウシグ、エリック・ウルフ、ロナルド・ダウスらがいる。 人類学的研究と分析において増加傾向にあるのが、ジョージ・マーカスの論文「世界システムにおける/世界システムについての民族誌:マルチサイト民族誌の 出現」で論じられたマルチサイト民族誌の活用である。文化をグローバルな社会秩序という巨視的構築物に埋め込まれたものと捉えるマルチサイト・民族誌は、 空間的・時間的に異なる複数の場所で伝統的な方法論を用いる。この方法論を通じて、世界システムが地域社会やグローバルコミュニティに与える影響を検証す る際、より深い洞察が得られる。 また、マルチサイト民族誌学では、文化研究、メディア研究、科学技術研究などからの手法を取り入れた、より高度な学際的アプローチがフィールドワークに現 れている。マルチサイト民族誌学では、研究対象を空間的・時間的境界を超えて追跡する。例えば、特定の商品といった「もの」がグローバル資本主義のネット ワークを通って輸送される過程を追うマルチサイト民族誌学が考えられる。 また、離散した民族集団、複数の場所や時代に出現する物語や噂、複数の民族誌的場所に見られる隠喩、あるいは空間と時間を超えて移動する個人や集団の伝記 を追うこともある。境界を越える紛争を追う場合もある。複数地点の民族誌の例として、ナンシー・シェパー=ヒューズの国際的な人体臓器闇市場に関する研究 がある。この研究では、臓器が資本主義の様々な合法・非合法ネットワークを通って移動する過程を追跡するとともに、貧困地域で流通する児童誘拐や臓器窃盗 に関する噂や都市伝説も追跡している。 社会文化人類学者は「西洋」文化への調査対象を次第に拡大している。例えばフィリップ・ブルゴワは1997年、ハーレムのクラック売場における起業家研究 『尊敬を求めて』でマーガレット・ミード賞を受賞した。また実験室研究者、ウォール街の投資家、法律事務所、情報技術(IT)コンピューター従業員といっ た専門職コミュニティの民族誌も人気を増している。[34] |

| Topics Kinship and family Main article: Kinship Kinship refers to the anthropological study of the ways in which humans form and maintain relationships with one another and how those relationships operate within and define social organization.[35] Research in kinship studies often crosses over into different anthropological subfields including medical, feminist, and public anthropology. This is likely due to its fundamental concepts, as articulated by linguistic anthropologist Patrick McConvell: Kinship is the bedrock of all human societies that we know. All humans recognize fathers and mothers, sons and daughters, brothers and sisters, uncles and aunts, husbands and wives, grandparents, cousins, and often many more complex types of relationships in the terminologies that they use. That is the matrix into which human children are born in the great majority of cases, and their first words are often kinship terms.[36] Throughout history, kinship studies have primarily focused on the topics of marriage, descent, and procreation.[37] Anthropologists have written extensively on the variations within marriage across cultures and its legitimacy as a human institution. There are stark differences between communities in terms of marital practice and value, leaving much room for anthropological fieldwork. For instance, the Nuer of Sudan and the Brahmans of Nepal practice polygyny, where one man has several marriages to two or more women. The Nyar of India and Nyimba of Tibet and Nepal practice polyandry, where one woman is often married to two or more men. The marital practice found in most cultures, however, is monogamy, where one woman is married to one man. Anthropologists also study different marital taboos across cultures, most commonly the incest taboo of marriage within sibling and parent-child relationships. It has been found that all cultures have an incest taboo to some degree, but the taboo shifts between cultures when the marriage extends beyond the nuclear family unit.[35] There are similar foundational differences where the act of procreation is concerned. Although anthropologists have found that biology is acknowledged in every cultural relationship to procreation, there are differences in the ways in which cultures assess the constructs of parenthood. For example, in the Nuyoo municipality of Oaxaca, Mexico, it is believed that a child can have partible maternity and partible paternity. In this case, a child would have multiple biological mothers in the case that it is born of one woman and then breastfed by another. A child would have multiple biological fathers in the case that the mother had sex with multiple men, following the commonplace belief in Nuyoo culture that pregnancy must be preceded by sex with multiple men in order have the necessary accumulation of semen.[38] |

トピック 親族関係と家族 主な記事: 親族関係 親族関係とは、人類学における研究分野であり、人間が互いに形成し維持する関係性、そしてそれらの関係性が社会組織内でどのように機能し定義するかを扱うものである。[35] 親族関係研究は、医療人類学、フェミニスト人類学、公共人類学など、異なる人類学のサブ分野と頻繁に交差する。これはおそらく、言語人類学者パトリック・マッコンベルが述べたように、その根本的な概念に起因するものである: 親族関係は、我々が知るあらゆる人間社会の基盤である。全ての人間は、父や母、息子や娘、兄弟姉妹、叔父や叔母、夫や妻、祖父母、いとこ、そして往々にし てさらに複雑な関係性を、自らが用いる用語体系の中で認識している。これは大多数の場合において、人間の子供が生まれる基盤であり、彼らの最初の言葉は往 々にして親族関係を表す用語である。[36] 歴史を通じて、親族研究は主に婚姻、血統、生殖といった主題に焦点を当ててきた。[37] 人類学者は、文化間における婚姻の多様性や、人間制度としてのその正当性について広く論じてきた。婚姻の慣行や価値に関する共同体間の顕著な差異は、人類 学的フィールドワークの余地を大きく残している。例えばスーダンのヌエル族やネパールのバラモンは一夫多妻制を実践し、一人の男性が複数の女性と結婚す る。インドのニャール族やチベット・ネパールのニンバ族は一妻多夫制を実践し、一人の女性が複数の男性と結婚することが多い。しかし大半の文化で見られる 婚姻慣行は一夫一婦制であり、一人の女性が一人の男性と結婚する。人類学者はまた、文化間における異なる婚姻タブー、特に兄弟姉妹や親子関係内での婚姻を 禁じる近親相姦タブーを研究する。あらゆる文化が程度の差こそあれ近親相姦タブーを有することが判明しているが、婚姻が核家族単位を超える場合、そのタ ブーは文化間で異なる。[35] 生殖行為に関しても同様の根本的な差異が存在する。人類学者は、あらゆる文化が生物学的な生殖関係を認識していることを確認しているが、親という概念を評 価する方法には文化間で差異がある。例えばメキシコ・オアハカ州ヌヨ地区では、子供は複数の生物学的母親と複数の生物学的父親を持つ可能性があると信じら れている。この場合、子供が一人の女性から生まれ、別の女性に授乳された場合、複数の生物学的母親を持つことになる。また、母親が複数の男性と性交した場 合、子供は複数の生物学的父親を持つことになる。これはヌヨ文化における一般的な信念、すなわち妊娠には必要な精液の蓄積を得るために複数の男性との性交 が先行しなければならないという考えに基づいている。[38] |

| Late twentieth-century shifts in interest In the twenty-first century, Western ideas of kinship have evolved beyond the traditional assumptions of the nuclear family, raising anthropological questions of consanguinity, lineage, and normative marital expectation. The shift can be traced back to the 1960s, with the reassessment of kinship's basic principles offered by Edmund Leach, Rodney Neeham, David Schneider, and others.[37] Instead of relying on narrow ideas of Western normalcy, kinship studies increasingly catered to "more ethnographic voices, human agency, intersecting power structures, and historical context".[39] The study of kinship evolved to accommodate for the fact that it cannot be separated from its institutional roots and must pay respect to the society in which it lives, including that society's contradictions, hierarchies, and individual experiences of those within it. This shift was progressed further by the emergence of second-wave feminism in the early 1970s, which introduced ideas of marital oppression, sexual autonomy, and domestic subordination. Other themes that emerged during this time included the frequent comparisons between Eastern and Western kinship systems and the increasing amount of attention paid to anthropologists' own societies, a swift turn from the focus that had traditionally been paid to largely "foreign", non-Western communities.[37] Kinship studies began to gain mainstream recognition in the late 1990s with the surging popularity of feminist anthropology, particularly with its work related to biological anthropology and the intersectional critique of gender relations. At this time, there was the arrival of "Third World feminism", a movement that argued kinship studies could not examine the gender relations of developing countries in isolation and must pay respect to racial and economic nuance as well. This critique became relevant, for instance, in the anthropological study of Jamaica: race and class were seen as the primary obstacles to Jamaican liberation from economic imperialism, and gender as an identity was largely ignored. Third World feminism aimed to combat this in the early twenty-first century by promoting these categories as coexisting factors. In Jamaica, marriage as an institution is often substituted for a series of partners, as poor women cannot rely on regular financial contributions in a climate of economic instability. In addition, there is a common practice of Jamaican women artificially lightening their skin tones in order to secure economic survival. These anthropological findings, according to Third World feminism, cannot see gender, racial, or class differences as separate entities, and instead must acknowledge that they interact together to produce unique individual experiences.[39] |

20世紀後半の関心事の変化 21世紀に入り、西洋における親族関係の概念は核家族という伝統的な前提を超えて発展し、血縁関係、系譜、規範的な婚姻期待といった人類学的な問題提起を 生んだ。この変化は1960年代に遡ることができ、エドマンド・リーチ、ロドニー・ニーハム、デイヴィッド・シュナイダーらによる親族関係の基本原理の再 評価が契機となった。[37] 西洋の狭義の規範に依存する代わりに、親族研究は次第に「より多くの民族誌的視点、人間の主体性、交差する権力構造、歴史的文脈」を取り入れるようになっ た。[39] 親族研究は、制度的基盤から切り離せず、矛盾や階層構造、構成員の個人的経験を含む社会そのものに敬意を払わねばならないという事実に対応する形で発展し た。この転換は、1970年代初頭に第二波フェミニズムが登場したことでさらに進展した。婚姻による抑圧、性的自律性、家庭内従属といった概念が導入され たのである。この時期に浮上した他のテーマには、東洋と西洋の親族制度の頻繁な比較や、人類学者自身の社会への注目度の高まりが含まれる。これは従来、主 に「外国の」、非西洋社会に注がれてきた焦点からの急激な転換であった。[37] 親族研究が主流の認知を得始めたのは1990年代後半、フェミニスト人類学の急激な普及と共にであった。特に生物人類学との関連研究や、ジェンダー関係の 交差性批判が契機となった。この時期に「第三世界フェミニズム」が登場し、親族研究は発展途上国のジェンダー関係を孤立して検証できず、人種的・経済的 ニュアンスにも配慮すべきだと主張した。この批判は、例えばジャマイカの人類学研究において関連性を帯びた。人種と階級が経済的帝国主義からの解放におけ る主要な障壁と見なされ、ジェンダーというアイデンティティはほぼ無視されていたのだ。第三世界フェミニズムは21世紀初頭、これらのカテゴリーを共存す る要因として推進することでこの状況に対抗しようとした。ジャマイカでは、経済不安定な状況下で貧しい女性が定期的な経済的支援を期待できないため、制度 としての結婚が一連のパートナー関係に置き換えられることが多い。加えて、ジャマイカ女性には経済的生存を確保するため、肌の色を人工的に明るくする慣行 が広く見られる。第三世界フェミニズムによれば、こうした人類学的知見は、性別・人種・階級の差異を独立した実体として捉えることはできず、それらが相互 に作用して独自の個人体験を生み出すことを認めねばならないのである。[39] |

| Rise of reproductive anthropology Kinship studies have also experienced a rise in the interest of reproductive anthropology with the advancement of assisted reproductive technologies (ARTs), including in vitro fertilization (IVF). These advancements have led to new dimensions of anthropological research, as they challenge the Western standard of biogenetically based kinship, relatedness, and parenthood. According to anthropologists Maria C. Inhorn and Daphna Birenbaum-Carmeli, "ARTs have pluralized notions of relatedness and led to a more dynamic notion of "kinning" namely, kinship as a process, as something under construction, rather than a natural given".[40] With this technology, questions of kinship have emerged over the difference between biological and genetic relatedness, as gestational surrogates can provide a biological environment for the embryo while the genetic ties remain with a third party.[41] If genetic, surrogate, and adoptive maternities are involved, anthropologists have acknowledged that there can be the possibility for three "biological" mothers to a single child.[40] With ARTs, there are also anthropological questions concerning the intersections between wealth and fertility: ARTs are generally only available to those in the highest income bracket, meaning the infertile poor are inherently devalued in the system. There have also been issues of reproductive tourism and bodily commodification, as individuals seek economic security through hormonal stimulation and egg harvesting, which are potentially harmful procedures. With IVF, specifically, there have been many questions of embryotic value and the status of life, particularly as it relates to the manufacturing of stem cells, testing, and research.[40] Current issues in kinship studies, such as adoption, have revealed and challenged the Western cultural disposition towards the genetic, "blood" tie.[42] Western biases against single parent homes have also been explored through similar anthropological research, uncovering that a household with a single parent experiences "greater levels of scrutiny and [is] routinely seen as the 'other' of the nuclear, patriarchal family".[43] The power dynamics in reproduction, when explored through a comparative analysis of "conventional" and "unconventional" families, have been used to dissect the Western assumptions of child bearing and child rearing in contemporary kinship studies. |

生殖人類学の台頭 近親関係研究においても、体外受精(IVF)を含む生殖補助医療技術(ARTs)の進歩に伴い、生殖人類学への関心が高まっている。これらの進歩は、西洋 の生物遺伝学に基づく近親関係、血縁性、親子の概念に疑問を投げかけることで、人類学研究に新たな次元をもたらした。人類学者マリア・C・インホルンとダ フナ・ビレンバウム=カルメリによれば、「ARTは血縁関係の概念を多様化し、より動的な『血縁形成』の概念、すなわち血縁を自然の与えられたものではな く、構築中のプロセスとして捉える考え方を生み出した」という。[40] この技術により、生物学的母性と遺伝的母性の差異をめぐる親族関係の問題が浮上した。妊娠代理母が胚の生物学的環境を提供しても、遺伝的絆は第三者に残る ためである。[41] 遺伝的母性、代理母性、養子縁組母性が関与する場合、人類学者は一人の子供に三人の「生物学的」母親が存在し得る可能性を認めている[40]。ARTsに は富と生殖能力の交差に関する人類学的疑問も存在する:ARTsは一般的に最高所得層のみが利用可能であり、不妊の貧困層は制度上本質的に軽視される。生 殖観光や身体の商品化の問題も存在する。個人が経済的安定を求めてホルモン刺激や卵子採取といった潜在的に有害な処置を受けるためだ。特に体外受精におい ては、胚の価値や生命の地位に関する疑問が数多く提起されている。これは幹細胞の製造、検査、研究と密接に関連している。[40] 養子縁組など親族研究における現代的課題は、西洋文化が遺伝的「血縁」を重視する傾向を明らかにし、その前提に疑問を投げかけている。[42] 同様の人類学的研究では、西洋社会における片親家庭への偏見も検証され、片親世帯は「より厳しい監視下に置かれ、核家族的・家父長制家族の『他者』として 日常的に見なされる」実態が明らかになった。[43] 「従来型」と「非従来型」家族を比較分析することで解明される生殖における力関係は、現代の親族関係研究において、西洋の出産・子育てに関する前提を分析 するために用いられてきた。 |

| Critiques of kinship studies Kinship, as an anthropological field of inquiry, has been heavily criticized across the discipline. One critique is that, as its inception, the framework of kinship studies was far too structured and formulaic, relying on dense language and stringent rules.[39] Another critique, explored at length by American anthropologist David Schneider, argues that kinship has been limited by its inherent Western ethnocentrism. Schneider proposes that kinship is not a field that can be applied cross-culturally, as the theory itself relies on European assumptions of normalcy. He states in the widely circulated 1984 book A critique of the study of kinship that "[K]inship has been defined by European social scientists, and European social scientists use their own folk culture as the source of many, if not all of their ways of formulating and understanding the world about them".[44] However, this critique has been challenged by the argument that it is linguistics, not cultural divergence, that has allowed for a European bias, and that the bias can be lifted by centering the methodology on fundamental human concepts. Polish anthropologist Anna Wierzbicka argues that "mother" and "father" are examples of such fundamental human concepts and can only be Westernized when conflated with English concepts such as "parent" and "sibling".[45] A more recent critique of kinship studies is its solipsistic focus on privileged, Western human relations and its promotion of normative ideals of human exceptionalism. In Critical Kinship Studies, social psychologists Elizabeth Peel and Damien Riggs argue for a move beyond this human-centered framework, opting instead to explore kinship through a "posthumanist" vantage point where anthropologists focus on the intersecting relationships of human animals, non-human animals, technologies and practices.[46] |

親族研究への批判 人類学の調査対象としての親族研究は、学問分野全体で激しく批判されてきた。一つの批判は、その創始期から、親族研究の枠組みが過度に構造化され定式であ り、難解な言語と厳格な規則に依存していた点だ[39]。もう一つの批判は、アメリカ人人類学者デイヴィッド・シュナイダーが詳細に論じたもので、親族研 究は本質的な西洋中心主義によって制限されてきたと主張する。シュナイダーは、親族研究は異文化間で適用可能な分野ではないと提案する。なぜなら理論自体 がヨーロッパの正常性に関する前提に依存しているからだ。彼は広く流通した1984年の著書『親族研究の批判』で「親族関係はヨーロッパの社会科学者に よって定義されてきた。そしてヨーロッパの社会科学者は、自らの民俗文化を、周囲の世界を構築し理解する手法の多く、あるいは全てにおける源泉として用い ている」と述べている[44]。しかしこの批判は、文化的差異ではなく言語学こそがヨーロッパ的偏向を許容したものであり、方法論を根本的人間概念に据え ることでその偏向は解消できるという反論に直面している。ポーランドの人類学者アンナ・ヴィエルジビツカは、「母」と「父」がそのような根本的人間概念の 例であり、これらが「親」や「兄弟」といった英語概念と混同された時に初めて西洋化されると主張する。[45] 近親関係研究に対するより最近の批判は、特権的な西洋の人間関係に自己中心的に焦点を当て、人間の例外性という規範的理想を推進している点にある。『批判 的親族研究』において、社会心理学者エリザベス・ピールとダミアン・リグスは、この人間中心の枠組みを超越することを主張する。代わりに、人類学者が人間 動物、非人間動物、技術、実践の交差する関係性に焦点を当てる「ポストヒューマニズム」の視点から親族関係を探求することを選択するのだ。[46] |

| Institutional anthropology The role of anthropology in institutions has expanded significantly since the end of the 20th century.[47] Much of this development can be attributed to the rise in anthropologists working outside of academia and the increasing importance of globalization in both institutions and the field of anthropology.[47] Anthropologists can be employed by institutions such as for-profit business, nonprofit organizations, and governments.[47] For instance, cultural anthropologists are commonly employed by the United States federal government.[47] The two types of institutions defined in the field of anthropology are total institutions and social institutions.[48] Total institutions are places that comprehensively coordinate the actions of people within them, and examples of total institutions include prisons, convents, and hospitals.[48] Social institutions, on the other hand, are constructs that regulate individuals' day-to-day lives, such as kinship, religion, and economics.[48] Anthropology of institutions may analyze labor unions, businesses ranging from small enterprises to corporations, government, medical organizations,[47] education,[8] prisons,[2][6] and financial institutions.[15] Nongovernmental organizations have garnered particular interest in the field of institutional anthropology because they are capable of fulfilling roles previously ignored by governments,[1] or previously realized by families or local groups, in an attempt to mitigate social problems.[47] The types and methods of scholarship performed in the anthropology of institutions can take a number of forms. Institutional anthropologists may study the relationship between organizations or between an organization and other parts of society.[47] Institutional anthropology may also focus on the inner workings of an institution, such as the relationships, hierarchies and cultures formed,[47] and the ways that these elements are transmitted and maintained, transformed, or abandoned over time.[49] Additionally, some anthropology of institutions examines the specific design of institutions and their corresponding strength.[11] More specifically, anthropologists may analyze specific events within an institution, perform semiotic investigations, or analyze the mechanisms by which knowledge and culture are organized and dispersed.[47] In all manifestations of institutional anthropology, participant observation is critical to understanding the intricacies of the way an institution works and the consequences of actions taken by individuals within it.[50] Simultaneously, anthropology of institutions extends beyond examination of the commonplace involvement of individuals in institutions to discover how and why the organizational principles evolved in the manner that they did.[49] Common considerations taken by anthropologists in studying institutions include the physical location at which a researcher places themselves, as important interactions often take place in private, and the fact that the members of an institution are often being examined in their workplace and may not have much idle time to discuss the details of their everyday endeavors.[51] The ability of individuals to present the workings of an institution in a particular light or frame must additionally be taken into account when using interviews and document analysis to understand an institution,[50] as the involvement of an anthropologist may be met with distrust when information being released to the public is not directly controlled by the institution and could potentially be damaging.[51] |

制度人類学 20世紀末以降、制度における人類学の役割は著しく拡大した。[47] この発展の多くは、学界外で活動する人類学者の増加と、制度および人類学分野におけるグローバル化の重要性増大に起因する。[47] 人類学者は営利企業、非営利組織、政府などの機関に雇用されることがある。[47] 例えば、文化人類学者は米国連邦政府に雇用されることが一般的だ。[47] 人類学の分野で定義される二種類の制度は、総括的制度と社会的制度である。[48] 総括的制度とは、内部の人々の行動を包括的に調整する場所であり、刑務所、修道院、病院などがその例である。[48] 一方、社会的制度とは、親族関係、宗教、経済など、個人の日常生活を規制する構築物である。[48] 制度人類学は、労働組合、中小企業から大企業までの事業体、政府、医療機関[47]、教育[8]、刑務所[2][6]、金融機関[15]などを分析対象と し得る。非政府組織(NGO)は、政府がこれまで無視してきた役割[1]、あるいは家族や地域集団が担ってきた役割を、社会問題の緩和を試みる形で果たし 得るため、制度人類学の分野で特に注目されている。[47] 制度人類学における研究の種類と方法は多様な形態をとる。制度人類学者は組織間、あるいは組織と社会他の部分との関係を研究する。[47]また制度内部の 仕組み、例えば形成される関係性・階層・文化[47]、そしてこれらの要素が時間とともに伝達・維持・変容・放棄される過程に焦点を当てることもある。 [49] さらに、制度人類学の一部は、制度の具体的な設計とその対応する強固さを検証する。[11] より具体的には、人類学者は制度内の特定の事象を分析したり、記号論的調査を行ったり、知識と文化が組織化・拡散されるメカニズムを分析したりする。 [47] あらゆる形態の制度人類学において、参与観察は制度の複雑な作動様式や、制度内個人の行動がもたらす結果を理解する上で不可欠である[50]。同時に、制 度人類学は個人の制度への日常的関与の検証を超え、組織原理がなぜ、どのようにしてその形態へと進化したのかを解明しようとする。[49] 制度研究において人類学者が考慮すべき共通事項には、重要な相互作用が非公開で行われることが多いことから研究者が自らを置く物理的場所、そして制度の構 成員が職場で観察されることが多く、日常業務の詳細を議論する余裕が乏しいという事実が含まれる。[51] インタビューや文書分析を用いて制度を理解する際には、個人が制度の働きを特定の視点や枠組みで提示する能力も考慮しなければならない[50]。なぜな ら、公に開示される情報が制度によって直接管理されておらず、潜在的に有害となる可能性がある場合、人類学者の関与は不信感をもって迎えられかねないから だ[51]。 |

| Age-area hypothesis – Concept in cultural anthropology Anthropology of religion – Study of religion in relation to other social institutions Bibliography of anthropology Ceremonial pole – Stake or post used in ritual practice Community studies – Academic field in the study of community Communitas – Latin noun for an unstructured community Cross-cultural psychology – Scientific study of human behaviour Cultural psychology – How cultures reflect and shape their psychology Cultural evolution – Evolutionary theory of social change Cultural relativism – Anthropological view Culture change – Term in public policy Culturology – Branch of social sciences Digital anthropology – Subdiscipline of anthropology Engaged theory – Comprehensive critical theory Ethnobotany – Study of traditional plant use Ethnomusicology – Study of the cultural aspects of music Ethnozoology – Study of human and animal interaction Folkloristics – Branch of anthropology Guilt–shame–fear spectrum of cultures – Main emotion used for social control Intangible cultural heritage – Class of UNESCO designated cultural heritage Kluckhohn and Strodtbeck's values orientation theory Nomad – Person without fixed habitat Sociology of culture – Branch of the discipline of sociology |

年齢領域仮説 – 文化人類学における概念 宗教人類学 – 他の社会制度との関係における宗教の研究 人類学の参考文献 儀式柱 – 儀礼の際に用いられる杭や柱 共同体研究 – 共同体を研究する学問分野 コミューニタス – 構造化されていない共同体を指すラテン語の名詞 文化間心理学 – 人間の行動を科学的に研究する学問 文化心理学 – 文化が心理学を反映し形成する方法 文化進化論 – 社会変化の進化論的理論 文化相対主義 – 人類学的な見解 文化変化 – 公共政策における用語 文化学 – 社会科学の一分野 デジタル人類学 – 人類学のサブ分野 エンゲージド理論 – 包括的な批判理論 民族植物学 – 伝統的な植物利用の研究 民族音楽学 – 音楽の文化的側面の研究 民族動物学 – 人間と動物の相互作用の研究 民俗学 – 人類学の一分野 罪悪感・恥・恐怖の文化スペクトル – 社会統制に用いられる主要感情 無形文化遺産 – ユネスコ指定文化遺産の一種 クラックホーンとストロットベックの価値観指向理論 遊牧民 – 固定した居住地を持たない人格 文化社会学 – 社会学の一分野 |