反時代的教養論

Promotion of Evil, or being bad

(詳細モード版)

| The Force is

a metaphysical and ubiquitous power in the Star Wars fictional

universe. "Force-sensitive" characters use the Force throughout the

franchise. Heroes like the Jedi seek to "become one with the Force",

matching their personal wills with the will of the Force, while the

Sith and other villains exploit the Force and try to bend it toward

their own selfish and destructive desires. The Force has been compared

to aspects of several world religions, and the phrase "May the Force be

with you" has become part of pop culture vernacular. |

フォースは 形而上学的なもので、スター・ウォーズという

フィクションの世界ではどこにでもある力だ。「フォースに感応する」キャラクターは、フランチャイズ全体を通してフォースを使用する。ジェダイのような英

雄は「フォースと一体化」しようとし、個人の意志とフォースの意志を一致させようとする。一方、シスやその他の悪役はフォースを悪用し、自分たちの利己的

で破壊的な欲望のためにフォースを曲げようとする。フォースはいくつかの世界宗教の側面と比較され、"May the Force be with

you"というフレーズはポップカルチャーの 慣用句の一部となっている。 |

Concept and development George Lucas created the concept of "the Force" both to advance the plot of Star Wars (1977) and to try to awaken a sense of spirituality in young audience members. Creation for the original films George Lucas created the concept of the Force to address character and plot developments in Star Wars (1977).[1] He also wanted to "awaken a certain kind of spirituality" in young audiences, suggesting a belief in God without endorsing any specific religion.[2] He developed the Force as a nondenominational religious concept, "distill[ed from] the essence of all religions", premised on the existence of God and distinct ideas of good and evil.[1] Lucas said there is a conscious choice between good and bad, and "the world works better if you're on the good side".[3] In 1970s San Francisco, where Lucas lived when he wrote the drafts that became Star Wars, New Age ideas that incorporated the concept of qi and other notions of a mystical life-force were "in the air" and widely embraced.[4] Lucas used the term the Force to "echo" its use by Canadian cinematographer Roman Kroitor in Arthur Lipsett's 21-87 (1963), a National Film Board production, in which Kroitor says, "Many people feel that in the contemplation of nature and in communication with other living things, they become aware of some kind of force, or something, behind this apparent mask which we see in front of us, and they call it God".[2] Although Lucas had Kroitor's line in mind specifically, Lucas said the underlying sentiment is universal and that "similar phrases have been used extensively by many different people for the last 13,000 years".[5] The first draft of Star Wars makes two references to "the Force of Others" and does not explain the concept: King Kayos utters the blessing "May the Force of Others be with you all", and he later says "I feel the Force also".[6] The power of the Force of Others is kept secret by the Jedi Bendu of the Ashla, an "aristocratic cult" in the second draft.[7][8] The second draft offers a lengthy explanation of the Force of Others and introduces its Ashla light side and Bogan dark side.[8] The Ashla and Bogan are mentioned 10 and 31 times, respectively, and the Force of Others plays a more prominent role in the story.[9] In this draft, Luke Starkiller's mission is to retrieve the Kyber Crystal, which can intensify either the Ashla or Bogan powers.[7] The film's shorter third draft has no references to the Ashla, but it mentions the Bogan eight times and Luke is still driven to recover the Kyber Crystal.[10][11] Lucas finished the fourth and near-final draft on January 1, 1976.[12] This version trims "the Force of Others" to "the Force", makes a single reference to the Force's seductive "dark side", distills an explanation of the Force to 28 words, and eliminates the Kyber Crystal.[13] Producer Gary Kurtz, who studied comparative religion in college, had long discussions with Lucas about religion and philosophy throughout the writing process.[14] Kurtz told Lucas he was unhappy with drafts in which the Force was connected with the Kyber Crystal, and he was also dissatisfied with the early Ashla and Bogan concepts.[14] "The act of living generates a force field, an energy. That energy surrounds us; when we die, that energy joins with all the other energy. There is a giant mass of energy in the universe that has a good side and a bad side. We are part of the Force because we generate the power that makes the Force live. When we die, we become part of that Force, so we never really die; we continue as part of the Force." —George Lucas during a production meeting for The Empire Strikes Back[15] Lucas and screenwriter Leigh Brackett decided that the Force and the Emperor would be the main concerns in The Empire Strikes Back (1980).[16] The focus on the Emperor was later shifted to Return of the Jedi (1983),[16] and the dark side of the Force was treated as The Empire Strikes Back's main villain.[17] Prequel films and midi-chlorians See also: Jedi § Prequel trilogy "Midichlorians" redirects here. For the bacteria, see Midichloria. The Phantom Menace (1999) introduces midi-chlorians (or midichlorians), microscopic creatures that connect characters to the Force. Lucas later requested a passage about midi-chlorians be retroactively added to notes written in August 1977 expanding on the nature of the Force.[18][19] Lucas based the concept on symbiogenesis,[20] calling midi-chlorians a "loose depiction" of mitochondria.[21] He further said: [Mitochondria] probably had something ... to do with the beginnings of life and how one cell decided to become two cells with a little help from this other little creature who came in, without whom life couldn't exist. And it's really a way of saying we have hundreds of little creatures who live on us, and without them, we all would die. There wouldn't be any life. They are necessary for us; we are necessary for them. Using them in the metaphor, saying society is the same way, says we all must get along with each other.[21] In a rough draft of Revenge of the Sith (2005), Palpatine says he "used the power of the Force to will the midichlorians to start the cell divisions that created" Anakin Skywalker.[22] This line was removed as the script progressed. Sequel films and other productions Lucas' story treatments for a potential sequel trilogy involved "a microbiotic world" and creatures known as the Whills, beings that "control the universe" and "feed off the Force." He elaborated that individuals function as "vehicles for the Whills to travel around in", and that midi-chlorians "communicate with the Whills [who] in a general sense ... are the Force."[23] After selling Lucasfilm to Disney in 2012, Lucas said his biggest concern about the franchise's future was the Force being "muddled into a bunch of gobbledegook".[24] When writing The Force Awakens (2015) with Lawrence Kasdan, J. J. Abrams respected that Lucas had established midi-chlorians' effect on some characters' ability to use the Force.[25] However, as a child, he interpreted Obi-Wan Kenobi's explanation of the Force in Star Wars to mean that any character could use its power, and that the Force was more grounded in spirituality than science.[25] Abrams retained the idea of the Force having a light and a dark side, and some characters' seduction by the dark side helps create conflict for the story.[26] Pablo Hidalgo of the Lucasfilm Story Group gave his "blessing" for writer-director Rian Johnson to introduce a new Force power in The Last Jedi (2017) "if the story required it and if it felt like it stretches into new territory but doesn't break the idea of what the Force can do."[27] Johnson observed that every Star Wars movie introduces new Force powers to meet that film's story needs.[27] Star Wars Rebels producer Dave Filoni cites several influences on how the Force is used in the show. The character Bendu—named in homage to the term Lucas originally associated with the Jedi—does not align with the franchise's normal dark-or-light duality, and this role is an extension of Filoni's conversations with Lucas about the nature of the Force.[28] Filoni credits the prequel films for better developing the concept of the Force, particularly the idea of a balance between the light and dark sides.[29] |

コンセプトと展開[編集] ジョージ・ルーカスは、『スター・ウォーズ』(1977年)のプロットを進めるためと、若い観客にスピリチュアリティの感覚を呼び覚まそうとするために、 「フォース」という概念を生み出した。 オリジナル映画のための創作[編集]。 ジョージ・ルーカスは『スター・ウォーズ』(1977年)のキャラクターとプロットの展開に対処するためにフォースの概念を創作した[1]。彼はまた、特 定の宗教を支持することなく神への信仰を示唆し、若い観客に「ある種の精神性を呼び覚ます」ことを望んでいた[2]。 [1]ルーカスは、善と悪の間には意識的な選択があり、「あなたが善の側にいる方が世界はうまくいく」と述べた[3]。ルーカスが『スター・ウォーズ』と なる草稿を書いたときに住んでいた1970年代のサンフランシスコでは、神秘的な生命力に関する気の概念やその他の概念を取り入れたニューエイジの思想が 「空気」の中にあり、広く受け入れられていた[4]。 ルーカスがフォースという言葉を使ったのは、カナダの撮影監督ロマン・クロイターが、ナショナル・フィルム・ボード制作のアーサー・リプセットの『21- 87』(1963年)の中で使った言葉を「反響」させるためだった。 [2]ルーカスはクロイターのセリフを特に念頭に置いていたが、ルーカスはその根底にある感情は普遍的なものであり、「過去13,000年の間、様々な人 々によって似たようなフレーズが広く使われてきた」と述べている[5]。 スター・ウォーズ』の最初の草稿では、「他者のフォース」について2回言及されているが、その概念については説明されていない: ケイオス王は「フォース・オブ・アザーズが皆と共にあらんことを」と祝福の言葉を口にし、後に「私もフォースを感じる」と述べている[6]。フォース・オ ブ・アザーズの力は、第2稿では「貴族の教団」であるアシュラのジェダイ・ベンドゥによって秘密にされている[7][8]。 [この草稿では、ルーク・スターキラーの使命はカイバークリスタルを回収することであり、カイバークリスタルはアシュラとボーガンのどちらの力も強めるこ とができる[7]。 ルーカスは1976年1月1日に第4稿とほぼ最終稿を完成させた[12]。このバージョンは「他者のフォース」を「フォース」に削り、フォースの魅惑的な 「ダークサイド」に1回言及し、フォースの説明を28語に絞り、カイバー・クリスタルを削除した[13]。 [13]大学で比較宗教学を専攻したプロデューサーのゲイリー・カーツは、執筆過程を通じて宗教と哲学についてルーカスと長い間議論していた[14]。 カーツはルーカスに、フォースがカイバークリスタルと結びついた草稿に不満があり、初期のアシュラとボーガンのコンセプトにも不満があると語った [14]。 「生きるという行為は力場、エネルギーを生み出す。そのエネルギーは私たちを取り囲んでいる。私たちが死ぬと、そのエネルギーは他のすべてのエネルギーと 結合する。宇宙には巨大なエネルギーの塊があり、良い面と悪い面がある。私たちはフォースの一部であり、フォースを生かす力を生み出しているからだ。私た ちは死んでもフォースの一部になる。 -帝国の逆襲 』の制作会議中の ジョージ・ルーカス[15]。 ルーカスと脚本家のリー・ブラケットは、フォースと皇帝が『帝国の 逆襲』(1980年)の主な関心事であると決めた[16]。 前日譚映画とミディ=クロリアン[編集]。 以下も参照のこと: ジェダイ§前日譚三部作 "ミディクロリアン "はここにリダイレクトされる。バクテリアについてはミディクロリアを参照のこと。 ファントム・メナス』(1999年)ではミディ=クロリアン(またはミディクロリアン)が登場する。ルーカスは後に、1977年8月に書かれたフォースの 本質を拡張するメモに、ミディ=クロリアンに関する一節を遡及的に追加するよう要請した[18][19]。ルーカスはこの概念を共生発生に基づいており [20]、ミディ=クロリアンをミトコンドリアの「ゆるい描写」と呼んでいる[21]。 彼はさらにこう述べている: [ミトコンドリアはおそらく......生命の始まりと、1つの細胞がどうやって2つの細胞になることを決めたのかに関係している。そしてそれは、私たち には何百もの小さな生き物が住んでいて、彼らがいなければ私たちはみんな死んでしまう。生命は存在しない。彼らは私たちにとって必要な存在であり、私たち は彼らにとって必要な存在なのだ。彼らを比喩に使うことで、社会も同じだと言い、私たちは皆、お互いに仲良くしなければならないと言うのだ[21]。 『シスの復讐』(2005年)のラフ案では、パルパティーンはアナキン・スカイウォーカーを「生み出す細胞分裂を開始させるためにミディクロリアンに フォースの力を使った」と語っている[22]。 続編映画とその他の作品[編集]。 ルーカスは、続編3部作の可能性について、"微生物世界 "と、"宇宙を支配し"、"フォースを糧とする "存在であるウィルズとして知られるクリーチャーを扱ったストーリーを考えていた。彼は、個体は「ウィルたちが移動するための乗り物」として機能し、ミ ディ=クロリアンは「一般的な意味で......フォースであるウィルたちとコミュニケーションする」と詳しく説明した[23]。2012年にルーカス フィルムを ディズニーに売却した後、ルーカスはフランチャイズの将来についての最大の懸念は、フォースが「ごちゃごちゃに混同されてしまうこと」だと語った [24]。 フォースの覚醒』(2015年)をローレンス・カスダンと執筆する際、J・J・エイブラムスはルーカスが一部のキャラクターのフォース使用能力にミディ= クロリアンの効果を確立したことを尊重した。 [25]しかし、彼は子供の頃、『スター・ウォーズ』におけるオビ=ワン・ケノービのフォースの説明を、どんなキャラクターでもその力を使うことができる という意味に解釈し、フォースは科学よりも精神性に根ざしていると考えた[25]。 [26]ルーカスフィルム・ストーリー・グループのパブロ・ヒダルゴは、脚本家であり監督であるリアン・ジョンソンが 『最後のジェダイ』(2017年)で新しいフォースの力を導入することに「ストーリーがそれを必要とし、それが新しい領域に伸びると感じられるが、フォー スにできることの考えを壊さないのであれば」[27]、「スター・ウォーズ」の映画は毎回、その映画のストーリーの必要性を満たすために新しいフォースの 力を導入しているとの見解を示した[27]。 スター・ウォーズ 反乱者たち』のプロデューサーであるデイヴ・フィローニは、番組内でのフォースの使われ方について、いくつかの影響を挙げている。ベンドゥというキャラク ターは、ルーカスが元々ジェダイに関連付けていた言葉へのオマージュとして命名されたもので、フランチャイズの通常のダーク・ライトの二元性とは一致して おらず、この役割はフォースの性質についてのルーカスとの会話の延長線上にある。 |

Depiction Illustration of an Imperial stormtrooper being hurled through massive rock columns by an opponent using the Force This concept art by Greg Knight of a stormtrooper being "Force pushed" was an early visualization of how the Force would be depicted in LucasArts' The Force Unleashed (2008).[30] "Jedi mind trick" redirects here. For the band, see Jedi Mind Tricks. Obi-Wan Kenobi describes the Force as "an energy field created by all living things" in Star Wars. In The Phantom Menace, Qui-Gon says microscopic lifeforms called midi-chlorians, which exist inside all living cells, allow some characters to be Force-sensitive; characters must have a high enough midi-chlorian count to feel and use the Force. Midi-chlorians are sentient,[1] and arguably were the first species to emerge in the Star Wars universe.[31] The species was a foundation of all life, as some deemed life impossible without midi-chlorians,[32] and ultimately resided in all living beings, connecting two aspects of the Force.[31] The Living Force (also known as a spirit or life essence)[33] is the energy generated by all living things.[34] Through midi-chlorians, it is fed into the Cosmic Force, which bounds all things and communicates with living sentient beings.[35] In 1981, Lucas compared using the Force to yoga, saying any character can use its power.[36] Dave Filoni said in 2015 that all Star Wars characters are "Force intuitive": some characters, like Luke Skywalker, are aware of their connection to the Force, while characters such as Han Solo draw upon the Force unconsciously.[37] Filoni said the most potent Force users are characters whose midi-chlorian count provides a natural affinity for using the Force and who undertake intense training and discipline.[38] Rogue One (2016) portrays the Force more as a religion "than simply a way to manipulate objects and people".[39] In the years following the Great Jedi Purge depicted in the prequel trilogy, some characters have lost faith in the Force,[40] and the Galactic Empire hunts down surviving Jedi and other Force-sensitive characters. By the time of the events in The Force Awakens, some characters think the Jedi and the Force are myths.[41] Some Force-sensitive characters derive special, psychic abilities from it, such as telekinesis, mind control, and extrasensory perception. The Force is sometimes referred to in terms of "dark" and "light" sides, with villains like the Sith drawing on the dark side to act aggressively while the Jedi use the light side for defense and peace.[42] According to Filoni, Lucas believed a character's intentions when using the Force—their "will to be selfless or selfish"—is what distinguishes light and dark sides.[29] The Force is also used by characters who are neither Jedi nor Sith, such as Leia Organa and Kylo Ren.[43][44] Characters throughout the franchise use their Force powers in myriad ways, including Obi-Wan using a "mind trick" to undermine a stormtrooper's will,[45][46] Darth Vader choking subordinates without touching them,[47] Qui-Gon Jinn repelling several battle droids at once, Rey lifting a large pile of rocks, and Kylo Ren stopping blaster fire in mid-air.[48][49] Film and television use of the Force is sometimes accompanied by a sound effect, such as a deep rumble associated with aggressive use or a more high-pitched sound associated with benevolent use.[50]  From left: Anakin Skywalker (Sebastian Shaw), Yoda (Frank Oz), and Obi-Wan Kenobi (Alec Guinness) appear as spirits at the end of the original version of Return of the Jedi. Jedi with special training can continue to exist after death, and some interact with the living as "being[s] of light"[51] referred to as "Force ghosts."[52][53] Obi-Wan's spirit provides Luke with guidance at key moments in the original trilogy,[53][54] and Yoda appears as a spirit to guide Luke in The Last Jedi.[55] Voices of past Jedi help Rey at the climax of The Rise of Skywalker, and Luke's and Leia's spirits watch over her at the film's conclusion.[56] In an early draft of Return of the Jedi, Lucas planned to resurrect Obi-Wan and Yoda at the climax,[57] and some drafts included scenes of the two helping Luke stop the Emperor.[58] The final arc of The Clone Wars' sixth season reveals that Qui-Gon Jinn learned how to transition into the "cosmic Force" from entities who represent various emotions;[53] Yoda hears the deceased Qui-Gon's voice in Attack of the Clones (2002), and he reveals in Revenge of the Sith that he has contact with Qui-Gon.[53] A short story by Claudia Gray depicts Obi-Wan learning this technique from Qui-Gon in the years leading up to Star Wars.[59] The Force plays an important role in several Star Wars plot lines. Anakin Skywalker's rise as a Jedi, descent into the Sith Lord Darth Vader, and redemption back to the light side of the Force is the main story arc for the first six Star Wars films.[60] Yoda's arc in the sixth season of The Clone Wars depicts him exploring "bigger questions" about the Force and taking various inspirations from the franchise's expanded universe.[61] In The Force Awakens, Finn's exposure to the Force helps make him question his training.[62] Writer Rian Johnson used the Force to allow Rey and Kylo Ren to communicate in The Last Jedi, developing the characters' relationship.[27] |

描写[編集] グレッグ・ナイトによるストームトルーパーが"フォース・プッシュ "されるコンセプト・アートは、ルーカスアーツの『フォース・アンリーシュド』(2008年)でフォースがどのように描かれるかを視覚化した初期のもので ある[30]。 "ジェダイ・マインド・トリック "はここにリダイレクトされる。バンドについては、ジェダイ・マインド・トリックを参照のこと。 オビ=ワン・ケノービは『スター・ウォーズ』の中で、フォースを「すべての生物が作り出すエネルギー・フィールド」と表現している。ファントム・メナス』 では、クワイ=ガンがミディ=クロリアンと呼ばれる微小な生命体がすべての生物の細胞内に存在し、一部のキャラクターがフォースを感じることができると 語っている。キャラクターがフォースを感じたり使ったりするには、ミディ=クロリアンの数が十分多くなければならない。ミディ=クロリアンは感覚を持ち [1]、間違いなくスター・ウォーズの世界で最初に出現した種族である[31]。ミディ=クロリアンなしでは生命は不可能と考える者もいるように、この種 族はすべての生命の基盤であり[32]、最終的にはすべての生物の中に存在し、フォースの2つの側面を結びつけている。 [31]リビング・フォース(スピリットまたはライフ・エッセンスとしても知られている)[33]は、すべての生物によって生成されるエネルギーである [34]。ミディ=クロリアンによって、それは万物を束縛し、生きている知覚を持つ生物と交信するコズミック・フォースに送り込まれる[35]。 ルーク・スカイウォーカーのようにフォースとのつながりを意識しているキャラクターもいれば、ハン・ソロのように無意識にフォースを利用しているキャラク ターもいる[37]。 [38] 『ローグ・ワン』(2016年)は、フォースを「単に物や人を操る方法というよりも」宗教として描いている[39]。前日譚三部作で描かれたジェダイの大 粛清から数年後、一部の登場人物はフォースへの信頼を失い[40]、銀河帝国は生き残ったジェダイやフォースに感応する人物を追い詰める。フォースの覚 醒』での出来事の頃には、ジェダイとフォースは神話だと考えるキャラクターもいる[41]。 フォースに感応するキャラクターの中には、テレキネシス、マインドコントロール、超感覚的知覚など、フォースから特殊な超能力を引き出す者もいる。フォー スは「ダークサイド」と「ライトサイド」という言葉で呼ばれることがあり、シスのような悪党が攻撃的に行動するためにダークサイドを利用するのに対し、 ジェダイは防衛と平和のためにライトサイドを利用する[42]。フィローニによると、ルーカスはフォースを使うときのキャラクターの意図、つまり「無私か 利己的であるかという意志」がライトサイドとダークサイドを区別するものだと考えていた[29]。レイア・オーガナや カイロ・レンのように、ジェダイでもシスでもないキャラクターもフォースを使う。 [43][44]オビ=ワンがストームトルーパーの意思を弱めるために「マインド・トリック」を使ったり、[45][46] ダース・ベイダーが部下に触れずに首を絞めたり、[47] クワイ=ガン・ジンが複数のバトル・ドロイドを一度に撃退したり、レイが大きな岩の山を持ち上げたり、カイロ・レンが空中でブラスターの火を止めたりと、 フランチャイズを通して登場人物は無数の方法でフォースの力を使う。 [48][49]映画やテレビでのフォースの使用は、攻撃的な使用に関連する深いゴロゴロ音や、慈悲深い使用に関連するより甲高い音などの効果音を伴うこ とがある[50]。  左から アナキン・スカイウォーカー(セバスチャン・ショウ)、ヨーダ(フランク・オズ)、オビ=ワン・ケノービ(アレック・ギネス)は、オリジナル版『ジェダイ の帰還』の最後に霊として登場する。 特別な訓練を受けたジェダイは死後も存在し続けることができ、「フォースの亡霊」と呼ばれる「光の存在」[51]として生者と交流する者もいる。 52][53]オビ=ワンの霊はオリジナル3部作の重要な場面でルークに導きを与え[53][54]、ヨーダは『最後のジェダイ』でルークを導く霊として 登場する[55]。『スカイウォーカーの逆襲』のクライマックスでは過去のジェダイの声がレイを助け、映画の結末ではルークとレイアの霊がレイを見守って いる。 [56]『ジェダイの帰還』の初期の草稿では、ルーカスはクライマックスでオビ=ワンとヨーダを復活させることを計画しており[57]、いくつかの草稿に は、2人がルークが皇帝を止めるのを助けるシーンが含まれていた。 [クローン・ウォーズ』第6シーズンの最終アークでは、クワイ=ガン・ジンが様々な感情を表す存在から「宇宙のフォース」に移行する方法を学んだことが明 らかにされている[53]。ヨーダは『クローンの攻撃』(2002年)で亡くなったクワイ=ガンの声を聞いており、『シスの復讐』ではクワイ=ガンと接触 していることを明かしている[53]。クローディア・グレイの短編小説では、オビ=ワンが『スター・ウォーズ』に至るまでの数年間にクワイ=ガンからこの 技法を学んだことが描かれている[59]。 フォースはスター・ウォーズのいくつかの筋書きで重要な役割を果たしている。アナキン・スカイウォーカーのジェダイとしての成長、シス卿ダース・ベイダー への転落、そしてフォースのライトサイドへの贖罪は、スター・ウォーズの最初の6作のメイン・ストーリー・アークである[60]。クローン・ウォーズの第 6シーズンにおけるヨーダのアークは、彼がフォースに関する「より大きな疑問」を探求し、フランチャイズの拡張宇宙から様々なインスピレーションを得るこ とを描いている。 [フォースの覚醒』では、フィンがフォースに触れることで、自分の訓練に疑問を抱くようになる[62]。 脚本家のリアン・ジョンソンは、『最後のジェダイ』でレイとカイロ・レンがコミュニケーションを取るためにフォースを使用し、キャラクターの関係を発展さ せた[27]。 |

| Analysis Chris Taylor called the Force "largely a mystery" in Star Wars.[3] Taylor ascribes the "more poetic, more spiritual ... and more demonstrative" descriptions of the Force in The Empire Strikes Back to Lawrence Kasdan, who co-wrote the film, but says the film does little to expand audiences' understanding of it.[3] In 1997, Lucas said that the more detail he articulated about the Force and how it works, the more it took away from its core meaning.[63] Kotaku suggests Rian Johnson depicted more nuance in the Force in The Last Jedi than Lucas did in his films.[64] According to Rob Weinert-Kendt, the "Force theme" in John Williams' score represents the power and responsibility of wielding the Force.[65] Comparison to magic Paranormal abilities like the Force are a common device in science fiction,[66] and the Force has been compared to the role magic plays in the fantasy genre.[67] The Star Wars films illustrate that characters not familiar with the particulars of the Force associate it with mysticism and magic, such as when an Imperial officer alludes to the "sorcerer's ways" of Darth Vader.[67] The depiction of the Force in Star Wars has been compared to that of magic in Harry Potter, with the former being described as more of a "spiritual force".[68] According to The A.V. Club, The Last Jedi depicts the Force "closer to the sorcery of fairy tales and medieval romance than it's ever been."[69] Eric Charles points out that the television films The Ewok Adventure (1984) and Ewoks: The Battle for Endor (1985), intended for children, are "fairy tales in a science fiction setting" which feature magic and other fairy tale motifs rather than the Force and science-fiction tropes.[70] These Ewok films have been described as depicting "sorcery" that is distinct from the Force powers depicted in the first six Star Wars films.[71] Drawing from the Star Wars roleplaying game sourcebook he co-authored in 1987, Bill Slavicsek says that "The Ewoks' mystical beliefs contain many references to the Force, though it is never named as such."[72] Religion and spirituality In his 1977 review of Star Wars, Vincent Canby of The New York Times called the Force "a mixture of what appears to be ESP and early Christian faith."[73] It has been studied in a religious context from an academic perspective.[74] The Magic of Myth compares the sharp distinction between the good "light side" and evil "dark side" of the Force to Zoroastrianism, which posits that "good and evil, like light and darkness, are contrary realities".[42] The connectedness between the light and dark sides has been compared to the relationship between yin and yang in Taoism,[75] although the balance between yin and yang lacks the element of evil associated with the dark side.[76] Taylor identifies other similarities between the Force and a Navajo prayer, prana, and qi.[19] It is a common plot device in jidaigeki films like The Hidden Fortress (1958), which inspired Star Wars, for samurai who master qi to achieve astonishing feats of swordsmanship.[77] Taylor added that the lack of detail about the Force makes it "a religion for the secular age".[3] According to Jennifer Porter, professor of religious studies at the Memorial University of Newfoundland, "the Force is a metaphor for godhood that resonates and inspires within [people] a deeper commitment to the godhood identified within their traditional faith".[78] According to Christian Pastor Clayton Keenan, "the spirituality of 'Star Wars' has to do with the Force. It's depicted as ... something supernatural within this universe, but it's not the same thing as a personal god that Christians or Jews or Muslims might believe in. It's this impersonal force that is in some ways this neutral, impersonal energy that is out there to be used for good or for evil."[79] At one point, Francis Ford Coppola suggested to George Lucas that they use their combined fortunes to start a religion based on the Force.[80] Practitioners of Jediism pray to and express gratitude to the Force.[81] Scientific analysis Scientists are mostly skeptical about a "real world" explanation for the Force.[82] Astrophysicist Jeanne Cavelos says in The Science of Star Wars that explaining the Force is particularly difficult because "it does so many different things".[83] Force powers like precognition imply the time travel of information.[84] Cavelos explores the possibility of brain implants or sensors being used to detect users' intent and manipulate energy fields, and compares such discipline to contemporary patients learning to control prosthetics.[85] A scientific explanation of the Force would require new discoveries in physics, such as unknown fields or particles[86] or a fifth force beyond the four fundamental interactions.[87] Flavio Fenton of the Georgia Institute of Technology School of Physics suggests a fifth force would carry two types of charge—one for the light side and one for the dark—and that each would be carried by its own particle.[88] Nepomuk Otte, also from Georgia Tech, cautions that Newton's third law of motion says telekinesis would apply a force back on the Force-wielding character.[88] Fabien Paillusson from the University of Lincoln argues that the Force of the Star Wars universe reflects our own quest for understanding the forces of the world we live in.[89] |

分析[編集] クリス・テイラーは『スター・ウォーズ』におけるフォースを「大部分は謎」と呼んだ[3]。テイラーは『帝国の逆襲』におけるフォースの「より詩的で、よ りスピリチュアルで......より実証的な」描写を、この映画を共同脚本したローレンス・カスダンのおかげだとしながらも、この映画は観客のフォースに 対する理解をほとんど広げていないと述べている[3]。 [3]1997年、ルーカスはフォースとその働きについて詳細に説明すればするほど、その核心的な意味から遠ざかってしまうと述べた[63]。 Kotakuは、リアン・ジョンソンが『最後のジェダイ』でフォースのニュアンスをルーカスの映画よりも多く描いたと示唆している[64]。 ロブ・ワイナート=ケントによれば、ジョン・ウィリアムズのスコアの「フォースのテーマ」はフォースを行使する力と責任を表している[65]。 魔法との比較[編集] フォースのような超常的な能力はSFでは一般的な装置であり[66]、フォースはファンタジーのジャンルで魔法が果たす役割と比較されてきた[67]。ス ター・ウォーズの映画では、帝国の将校がダース・ベイダーの「魔術師のやり方」を暗喩するなど、フォースの特殊性をよく知らない登場人物がフォースを神秘 主義や魔法と関連付けていることが描かれている。 [67] スター・ウォーズにおけるフォースの描写は、ハリー・ポッターにおける魔法の描写と比較されており、前者はより「精神的な力」として描写されている [68]。The A.V. Clubによると、『最後のジェダイ』はフォースを「これまでよりもおとぎ話や中世のロマンスの魔術に近い」と描いている[69]。 エリック・チャールズは、テレビ映画『イウォーク・アドベンチャー』(1984年)と『イウォーク』(1985年)を指摘している: エリック・チャールズは、子供向けのテレビ映画『The Ewok Adventure』(1984年)と『Ewoks:The Battle for Endor』(1985年)は「SF設定のおとぎ話」であり、フォースやSFのトピックではなく、魔法やその他のおとぎ話のモチーフをフィーチャーしてい ると指摘する[70]。これらのイウォーク映画は、スター・ウォーズの最初の6作品で描かれたフォースの力とは異なる「魔術」を描いていると説明されてい る。 [71]1987年に共著したスター・ウォーズのロールプレイング・ゲームのソースブックから、ビル・スラヴィセクは「イウォークの神秘的な信仰には フォースへの言及が多いが、フォースとして名付けられることはない」と述べている[72]。 宗教とスピリチュアリティ[編集]。 ニューヨーク・タイムズ』紙のヴィンセント・キャンビーは1977年の『スター・ウォーズ』の批評で、フォースを「超能力と初期キリスト教の信仰と思われ るものの混合物」と呼んだ[73]。 [74] The Magic of Mythは、フォースの善の「ライトサイド」と悪の「ダークサイド」の間の鋭い区別を、「善と悪は、光と闇のように、相反する実在である」と仮定するゾロ アスター教と比較している[42]。陰と陽のバランスはダークサイドに関連する悪の要素を欠いているが、ライトサイドとダークサイドの間の接続性は、道教 における 陰と陽の関係と比較されている[75]。 [76]テイラーは、フォースとナバホ族の祈り、プラーナ、気の間の他の類似点を特定している[19]。スター・ウォーズに影響を与えた『隠し砦の三悪 人』(1958年)のような時代劇映画では、気をマスターした侍が剣術の驚異的な技を達成するというのは、よくあるプロット装置である[77]。 [3] ニューファンドランド記念大学の宗教学教授であるジェニファー・ポーターによれば、「フォースは、伝統的な信仰の中で識別される神性へのより深いコミット メントを共鳴させ、[人々に]鼓舞する神性のメタファーである」[78]。キリスト教牧師のクレイトン・キーナンによれば、「『スター・ウォーズ』の霊性 はフォースと関係している。それは......この宇宙の中で超自然的なものとして描かれているが、キリスト教徒やユダヤ教徒やイスラム教徒が信じるよう な個人的な神とは違う。ある意味で中立的で、善にも悪にも使える非人間的なエネルギーなんだ」[79]。 ある時、フランシス・フォード・コッポラはジョージ・ルーカスに、フォースに基づく宗教を始めるために彼らの財力を結集することを提案した[80] 。 科学的分析[編集] 宇宙物理学者のジャンヌ・カヴェロスは 『スター・ウォーズの科学』の中で、フォースを説明するのは特に難しいと述べている。予知能力のようなフォースの力は情報のタイムトラベルを意味する [83]。 ジョージア工科大学物理学部のフラビオ・フェントンは、第5の力には2種類の電荷があり、1つは光側、もう1つは闇側の電荷で、それぞれが独自の粒子に よって運ばれると提案している[87]。 [88]同じくジョージア工科大学のネポムク・オッテは、ニュートンの運動の第三法則によれば、テレキネシスはフォースを行使するキャラクターに力を戻す と警告している[88]。リンカーン大学のファビアン・パイユソンは、スター・ウォーズの世界のフォースは、我々の住む世界の力を理解しようとする我々自 身の探求を反映していると主張している[89]。 |

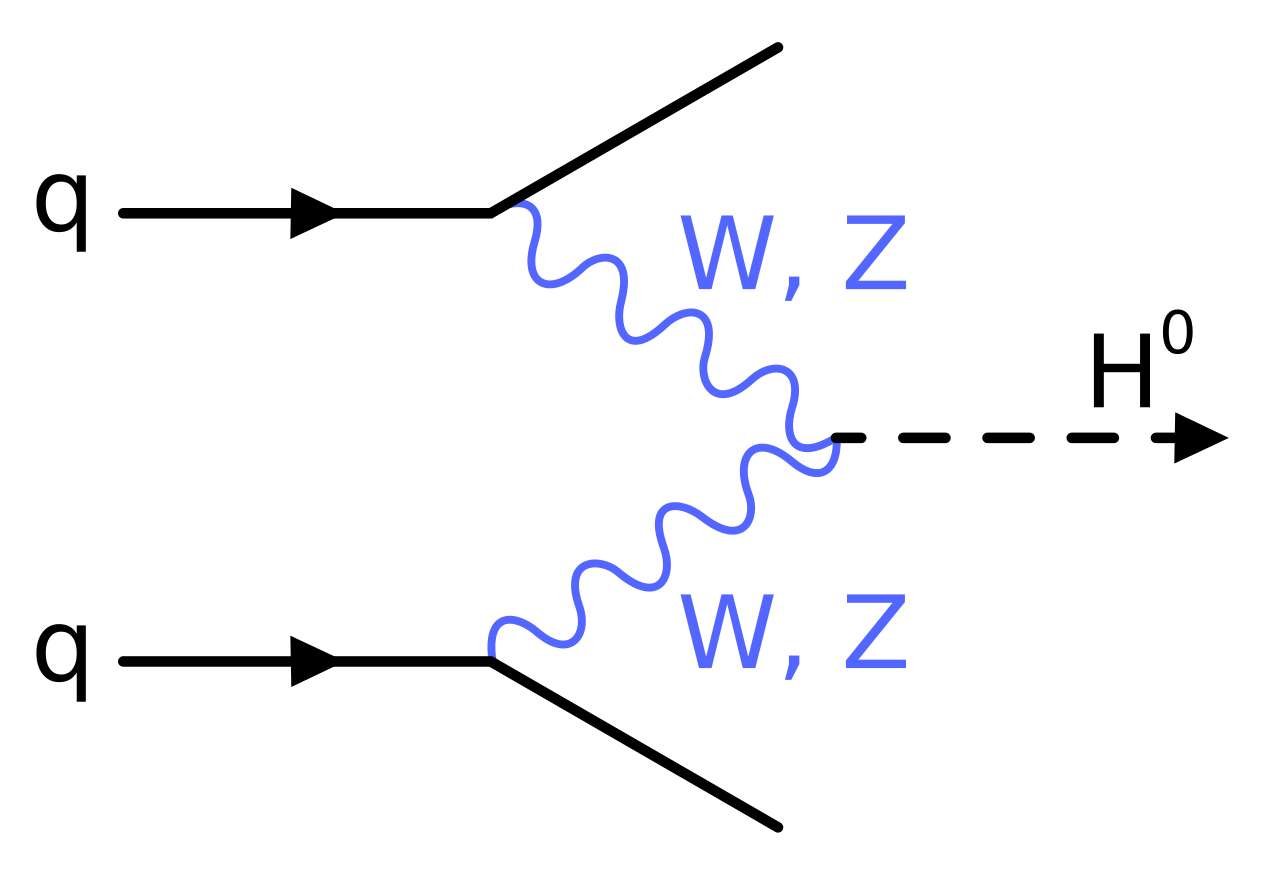

Cultural impact A Feynman diagram of one way the Higgs boson might be produced. National Geographic compared the boson's role in "carrying" the Higgs field to the way Jedi are "carriers" of the Force.[90] See also: Cultural impact of Star Wars National Geographic compared the Higgs boson's role as "carrier" of the Higgs field to the way Jedi are "carriers" of the Force.[90] A previsualization video highlighting the idea of "kicking someone's ass with the Force" steered LucasArts game designers toward producing The Force Unleashed (2008),[91][92] which sold six million copies as of July 2009.[93] In 2009, Uncle Milton Industries released a toy, called the Force Trainer, which uses EEG to read users' beta waves to lift a training droid-themed ball with a shaft of air.[94][95] The New Republic, Townhall, The Atlantic, and others have compared various political machinations to the "Jedi mind trick", a Force power used to undermine opponents' perceptions and willpower.[96][46][97][98] Critical response Critic Tim Robley compared the Force to the ruby slippers from The Wizard of Oz (1939), with both being entities that send the protagonist on a quest.[99] In her 1980 Washington Post review of The Empire Strikes Back, Judith Martin described the Force as "a mishmash of current cultic fashions without any base in ideas. It doesn't seem to be connected with ethics or a code of decent behavior, either."[100] John Simon wrote in his 1977 review of Star Wars for New York magazine: And then there is that distressing thing called the Force, which is ... Lucas's tribute to something beyond science: imagination, the soul, God in man ... It appears in various contradictory and finally nonsensical guises, a facile and perfunctory bow to metaphysics. I wish that Lucas had had the courage of his materialistic convictions, instead dragging in a sop to a spiritual force the main thrust of the movie so cheerfully ignores.[101][102] The introduction of midi-chlorians in The Phantom Menace was controversial, with Evan Narcisse of Time writing that the concept ruined Star Wars for him and a generation of fans because "the mechanisms of the Force became less spiritual and more scientific".[21] Film historian Daniel Dinello called midi-chlorians "anathema to Star Wars fanatics who thought they reduced the Force to a kind of viral infection."[103] Referring to "midi-chlorians" became a screenwriting shorthand for over-explaining a concept.[104] Although Chris Taylor suggested fans want less detail, not more, in explaining the Force,[3][105] Chris Bell argues that the introduction of midi-chlorians provided depth to the franchise and fomented engagement among fans and franchise writers.[104] Religion expert John D. Caputo writes, "In the 'Gospel according to Lucas' a world is conjured up in which the intractable oppositions that have tormented religious thinkers for centuries are reconciled ... The gifts that the Jedi masters enjoy have a perfectly plausible scientific basis, even if its ways are mysterious".[106] Characters' faith in the Force reinforces Rogue One's message of hope.[40] The A.V. Club said Rian Johnson's depiction of the Force in The Last Jedi goes "beyond George Lucas' original transcendental concept".[69] Polygon said Johnson's film "democratize[s] the Force", depicting Force sensitivity in characters from outside a "Force-sensitive lineage" and suggesting that the Force can be used by anyone.[107] "May the Force be with you" "May the Force be with you" redirects here. For other uses, see May the Force be with you (disambiguation). Several Star Wars characters say "May the Force be with you" (or derivatives of it) and the expression has become a popular catchphrase.[108] In 2005, "May the Force be with you" was chosen as number 8 on the American Film Institute's 100 Years... 100 Movie Quotes list.[109] May 4 is Star Wars Day, taken from the pun "May the Fourth be with you".[110] The expression was intentionally similar to the Christian dominus vobiscum, "the Lord be with you".[111] President Ronald Reagan in 1985 said "the Force is with us", referring to the United States, to create the Strategic Defense Initiative (itself often nicknamed Star Wars) to protect against Soviet ballistic missiles.[112] Some weeks earlier, Reagan had compared the Soviet Union to the Galactic Empire.[113] The Gospel According to Star Wars says that Reagan's invocation of the Force was actually perverting Star Wars' "self-dispossessing" (or other-focused) ethos: [The] blessing "May the Force be with you" is the expression of a hope for others ("May the Force be with you"), not for ourselves as with Reagan ("The Force is with us"). Moreover, the [Star Wars] blessing is precisely a request for hope for others ("May the Force be with you"), whereas Reagan's claim sounds like a possessive assertion ("The Force is with us").[114] |

文化的影響[編集] ヒッグス粒子が生成される可能性のある1つの方法のファインマン図。ナショナルジオグラフィックは、ヒッグス場を「運ぶ」というボソンの役割を、ジェダイ がフォースの「運び屋」であるのと比較している[90]。 以下も参照のこと: スター・ウォーズの文化的影響 ナショナルジオグラフィックは、ヒッグス粒子の「運び屋」としての役割を、ジェダイがフォースの「運び屋」である姿と比較した[90]。「フォースで誰か の尻を蹴飛ばす」というアイデアを強調したプレビジュアライゼーションビデオは、ルーカスアーツのゲームデザイナーを『フォース・アンリーシュド』 (2008年)の制作へと向かわせた[91][92]。 [93]2009年、アンクル・ミルトン・インダストリーは フォース・トレーナーと呼ばれる玩具を発売した。これは脳波を使ってユーザーのベータ波を読み取り、空気のシャフトでトレーニング・ドロイドをテーマにし たボールを持ち上げるものである[94][95]。 ニュー・リパブリック』、『タウンホール』、『アトランティック』などは、様々な政治的策略を「ジェダイのマインド・トリック」に例えており、これは相手 の認識や意志の力を弱めるために使われるフォースの力である[96][46][97][98]。 批評家の反応[編集] 批評家のティム・ロブリーはフォースを『オズの魔法使い』(1939年)のルビーの靴と比較し、どちらも主人公を探求に向かわせる存在であるとした [99]。 1980年の『帝国の逆襲』のワシントン・ポスト紙の批評で、ジュディス・マーティンはフォースを「アイデアのベースがなく、現在のカルト的な流行の寄せ 集め」と評した。倫理やまともな行動規範とも結びついていないようだ」[100][100] ジョン・サイモンは1977年の『ニューヨーク』誌の『スター・ウォーズ』評でこう書いている: そして、フォースという厄介なものがある。想像力、魂、人間の中の神......。それはさまざまな矛盾をはらみ、最後には無意味な装いで現れ、形而上学 への安易で場当たり的なお辞儀となる。私は、ルーカスに唯物論的な信念を貫く勇気があればよかったのにと思う。代わりに、映画の主旨があまりにも陽気に無 視している精神的な力へのおべっかを引きずっているのだ[101][102]。 ファントム・メナス』におけるミディ=クロリアンの導入は物議を醸し、『タイム』誌のエヴァン・ナルシスは、「フォースのメカニズムがスピリチュアルでは なく、科学的になった」[21]ため、このコンセプトが彼やファンの世代にとって『スター・ウォーズ』を台無しにしたと書いている。 映画史家のダニエル・ディネロは、ミディ=クロリアンを「フォースを一種のウイルス感染に貶めたと考えるスター・ウォーズ狂信者にとっては忌まわしい存 在」と呼んだ[103]。 [104]クリス・テイラーは、ファンはフォースの説明において、より詳細ではなく、より少ない詳細を望んでいると示唆したが[3][105]、クリス・ ベルは、ミディ=クロリアンの導入はフランチャイズに深みを与え、ファンとフランチャイズの作家の間の関与を促進したと主張している[104]宗教の専門 家であるジョン・D・カプトは、「『ルーカスによる福音書』では、何世紀にもわたって宗教思想家を苦しめてきた難解な対立が和解する世界が作り出されてい る......」と書いている。ジェダイ・マスターたちが享受する能力は、その方法が神秘的であるとしても、完全にもっともらしい科学的根拠を持ってい る」[106]。 登場人物たちのフォースへの信仰は、『ローグ・ワン』の希望のメッセージを強化する[40]。A.V.クラブは、『最後のジェダイ』におけるリアン・ジョ ンソンのフォースの描写は、「ジョージ・ルーカスのオリジナルの超越的な概念を超えている」と述べた[69]。ポリゴンは、ジョンソンの映画は「フォース を民主化」し、「フォース感受性の血筋」以外の登場人物たちのフォース感受性を描き、フォースは誰にでも使えることを示唆していると述べた[107]。 "フォースと共にあらんことを"[編集]。 "May the Force be with you "はこちらにリダイレクトされる。他の用法については、May the Force be with you (disambiguation) を参照のこと。 スター・ウォーズの登場人物の何人かは「フォースと共にあらんことを」(またはその派生語)と言っており、この表現は人気のキャッチフレーズとなっている [108]。2005年、「フォースと共にあらんことを」はアメリカ映画協会の100 Years... の8位に選ばれた[109]。この表現は、キリスト教のdominus vobiscum「主が共にあらんことを」と意図的に似ている[111]。 1985年のロナルド・レーガン大統領は、ソ連の 弾道ミサイルから身を守るための戦略防衛構想(それ自体がしばしばスター・ウォーズとあだ名される)を策定するために、アメリカを指して「フォースは我々 とともにある」と言った[112]。 その数週間前、レーガンはソ連を 銀河帝国に例えていた[113]。『スター・ウォーズによる福音書』は、レーガンのフォースの発動は、スター・ウォーズの「自らを捨て去る」(あるいは他 者に焦点を当てる)エートスを実際に曲解していたと述べている: [フォースが共にあらんことを」という祝福は、レーガンのように自分自身のためではなく(「フォースが我々と共にあらんことを」)、他者への希望の表現で ある。さらに、[スター・ウォーズの]祝福はまさに他者への希望(「フォースとともにあらんことを」)の要請であり、レーガンの主張は所有的主張 (「フォースは我々とともにある」)のように聞こえる[114]。 |

| Anima mundi Animism Brahman Force field (physics) Jediism Manitou Mysticism Mythopoeia Ontology Orenda Prana Psychic Qi Pneuma Sith |

アニマ・ムンディ アニミズム ブラフマン フォースフィールド(物理学) ジェダイ教 マニトゥー 神秘主義 神話 オントロジー オレンダ プラーナ サイキック 気 ニューマ シス |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Force |

|

1 ・反時代的とはなにか?(→歴史主義のジレンマからの克服法) |

|

2 1. 教養とはなにか 2. 倫理的とはなにか 3. 悪とはなにか? 4. 知的アナキズムのすすめ |

|

3 1. 教養とはなにか? |

|

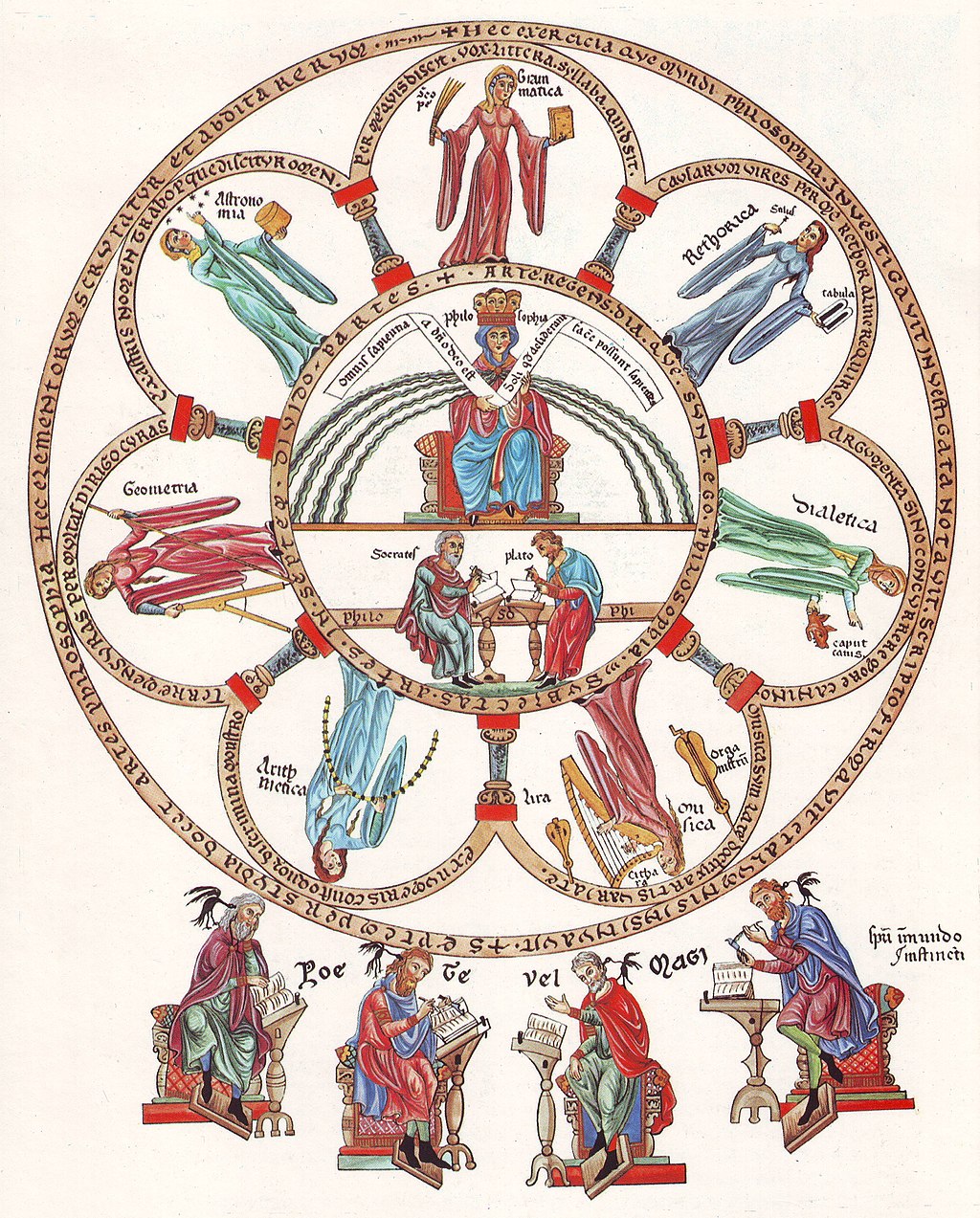

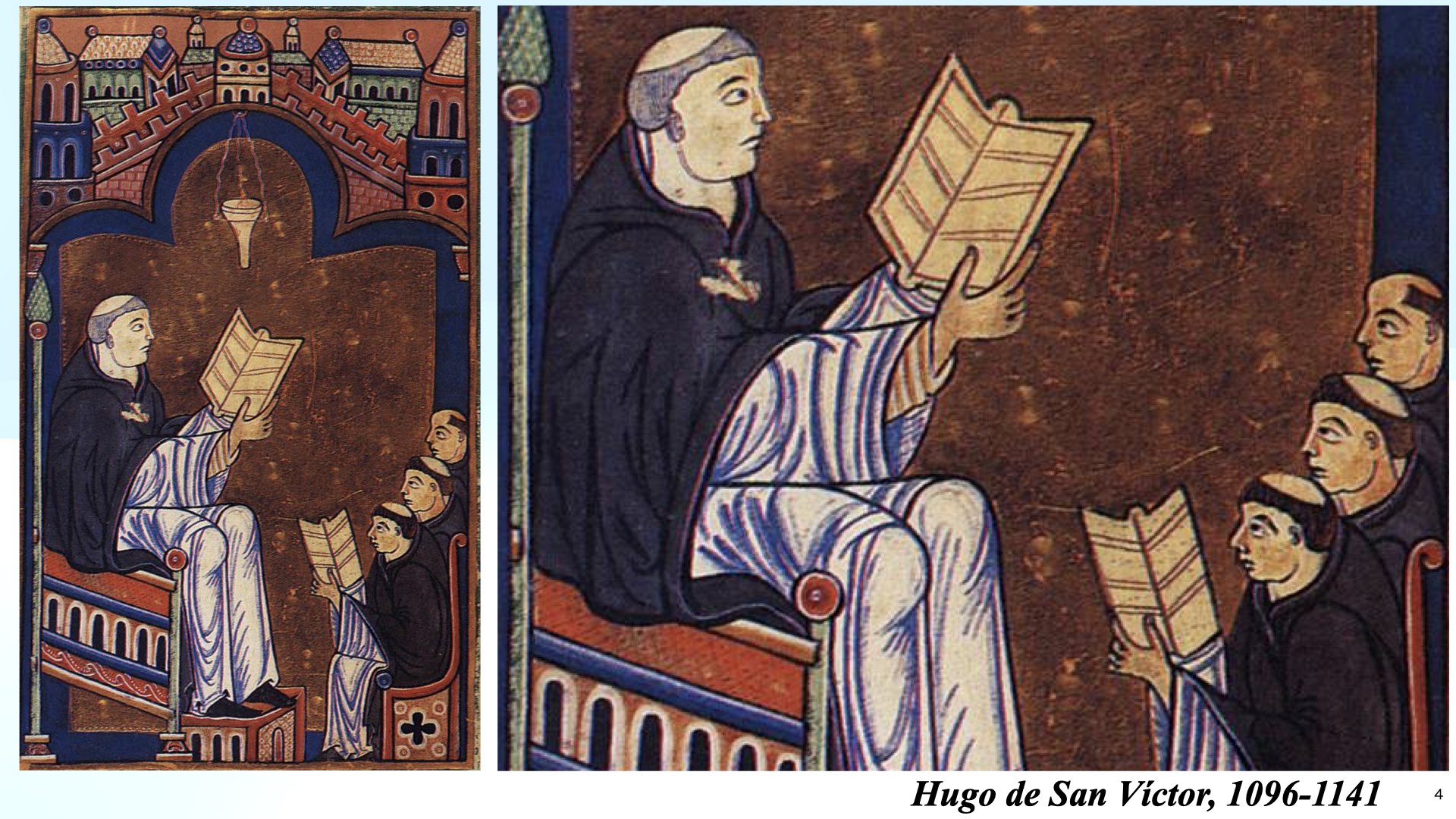

4 Hugo de San Victor. 日本における教養教育の2つの源流; ビルトゥングとリベラルアーツの共通点と相違点 |

|

5 ・ビルドゥング(教養) カントやヘーゲルなどの啓蒙主義哲学 教育を受けることは「教養」の過程の一部にすぎない 知識習得というよりも、自己がどのような疎外状況を克服するかということに価値を置く 外国語を学ぶことが「教養」とは単純には見なされていない スポーツに親しむ生活は、教養主義のレパートリーの中の一つ(=全体的人間) 古典的な受動的学習が中心 形式主義を嫌う——陶冶は個人が個々の疎外や葛藤から成長すること ・ |

|

6 ・ヘーゲルさん(→脳にコネックテッドされたヘーゲル) |

|

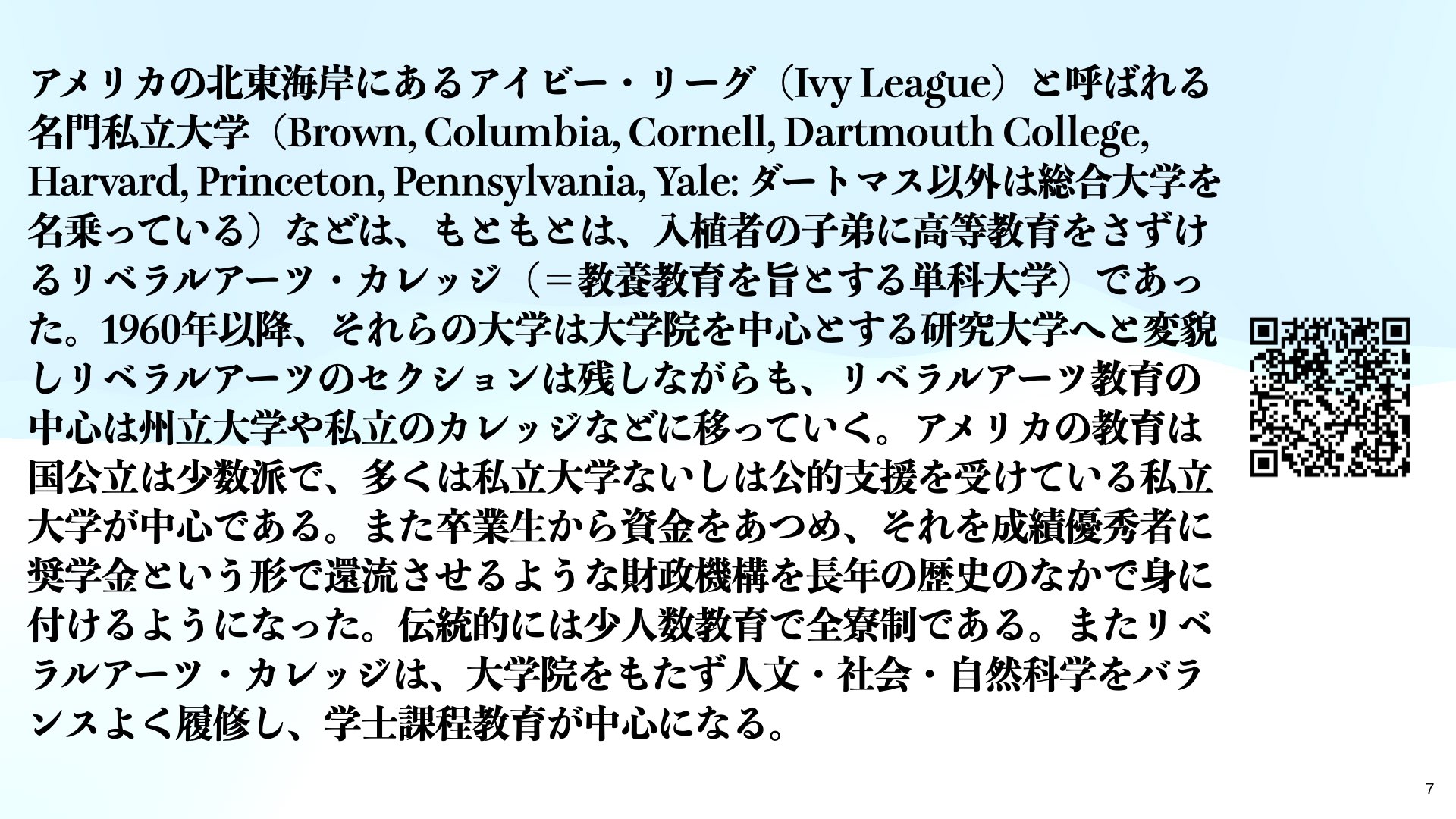

7 ・アイビーリーグ(→2つのリベラルアーツ教育:その共通点と相違点) |

|

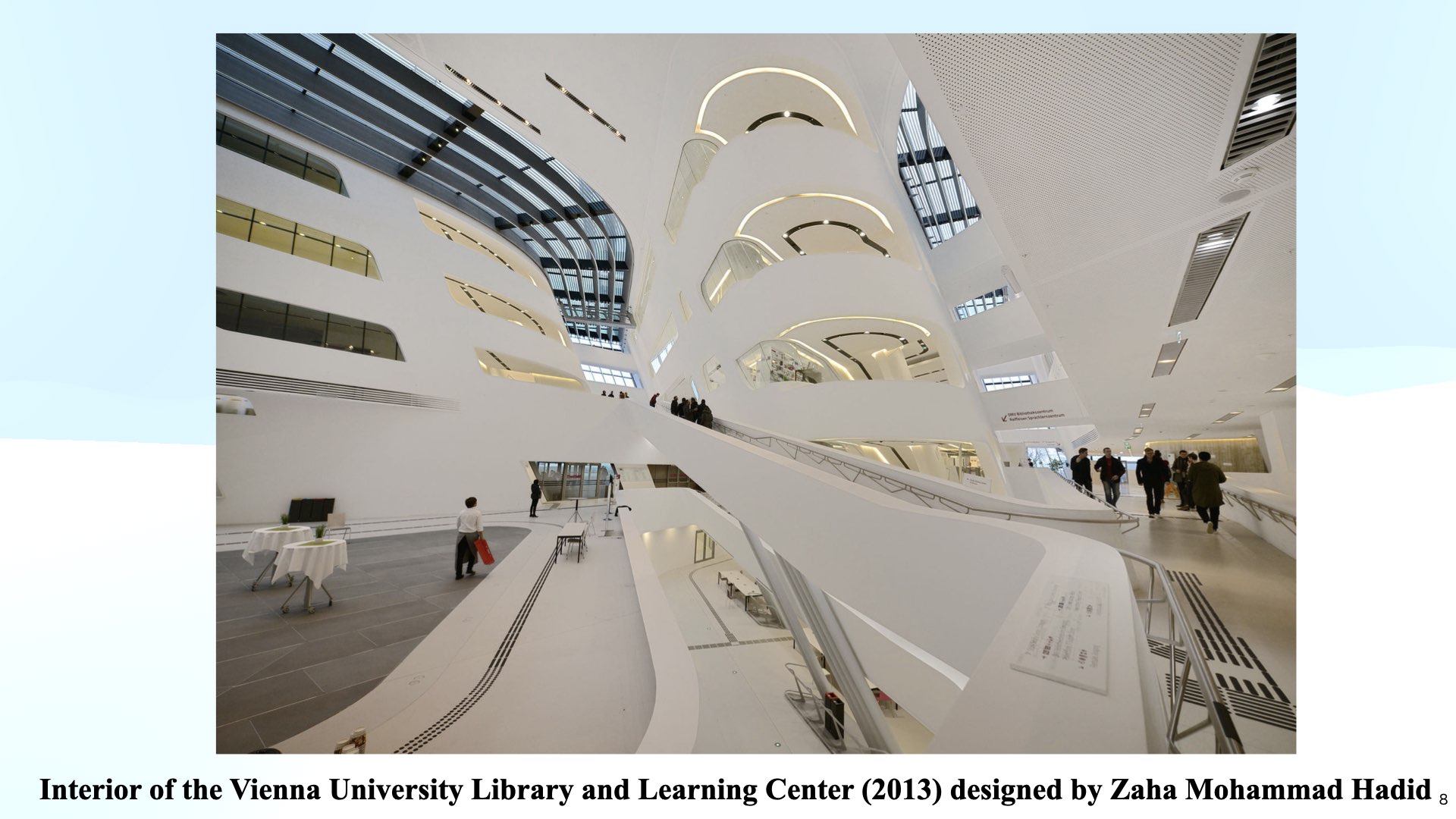

8 |

|

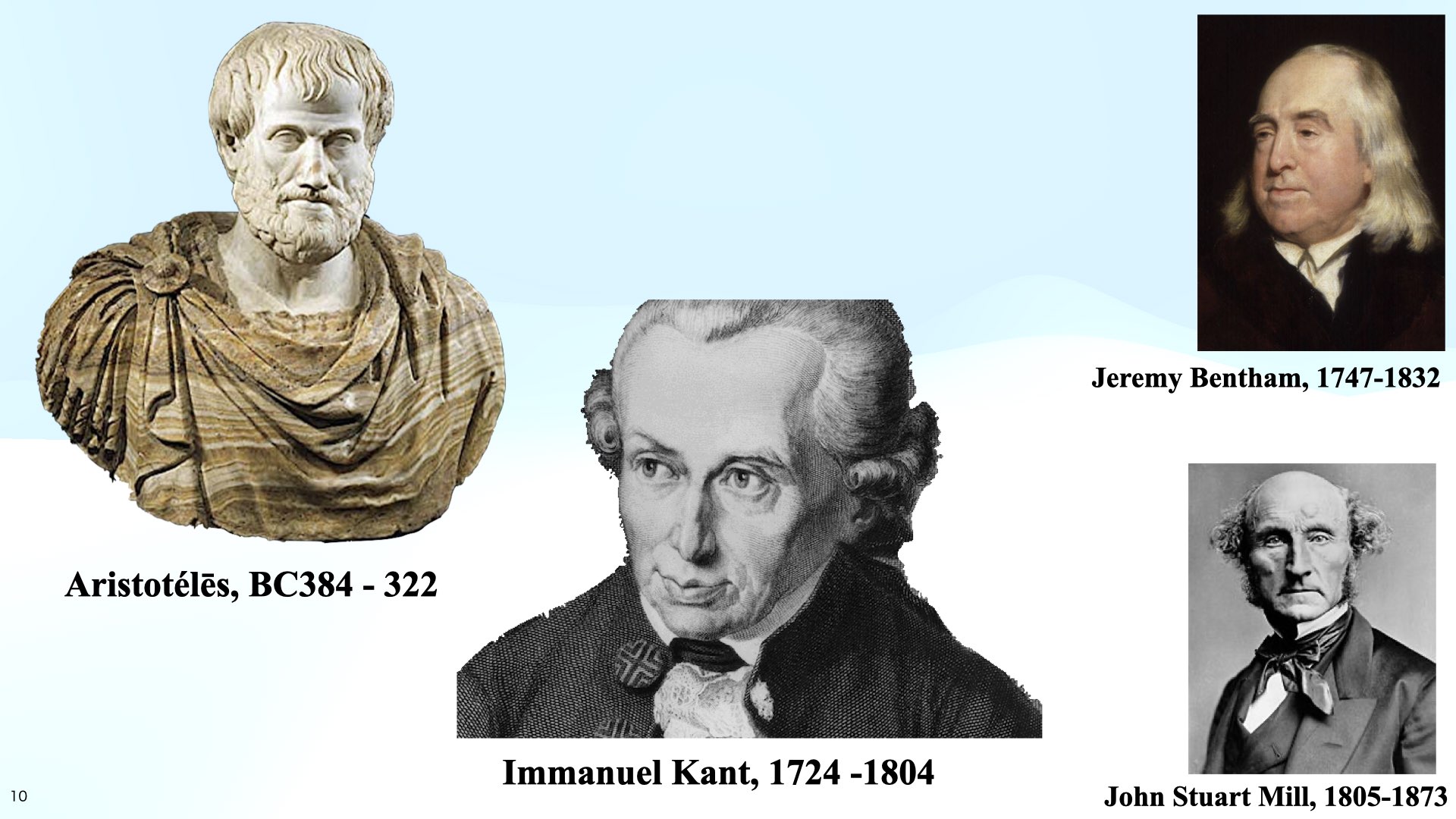

9 ・倫理的とはなにか? ・西洋倫理学の3つの伝統 |

|

10 ・西洋倫理学の3つの伝統 |

|

11 ・ジジェク派による根源的悪レクチャー |

|

12 ・ベンサム卿 |

|

13 ・悪とはなにか?(→悪ないしは邪悪に関するポータルサイト) |

|

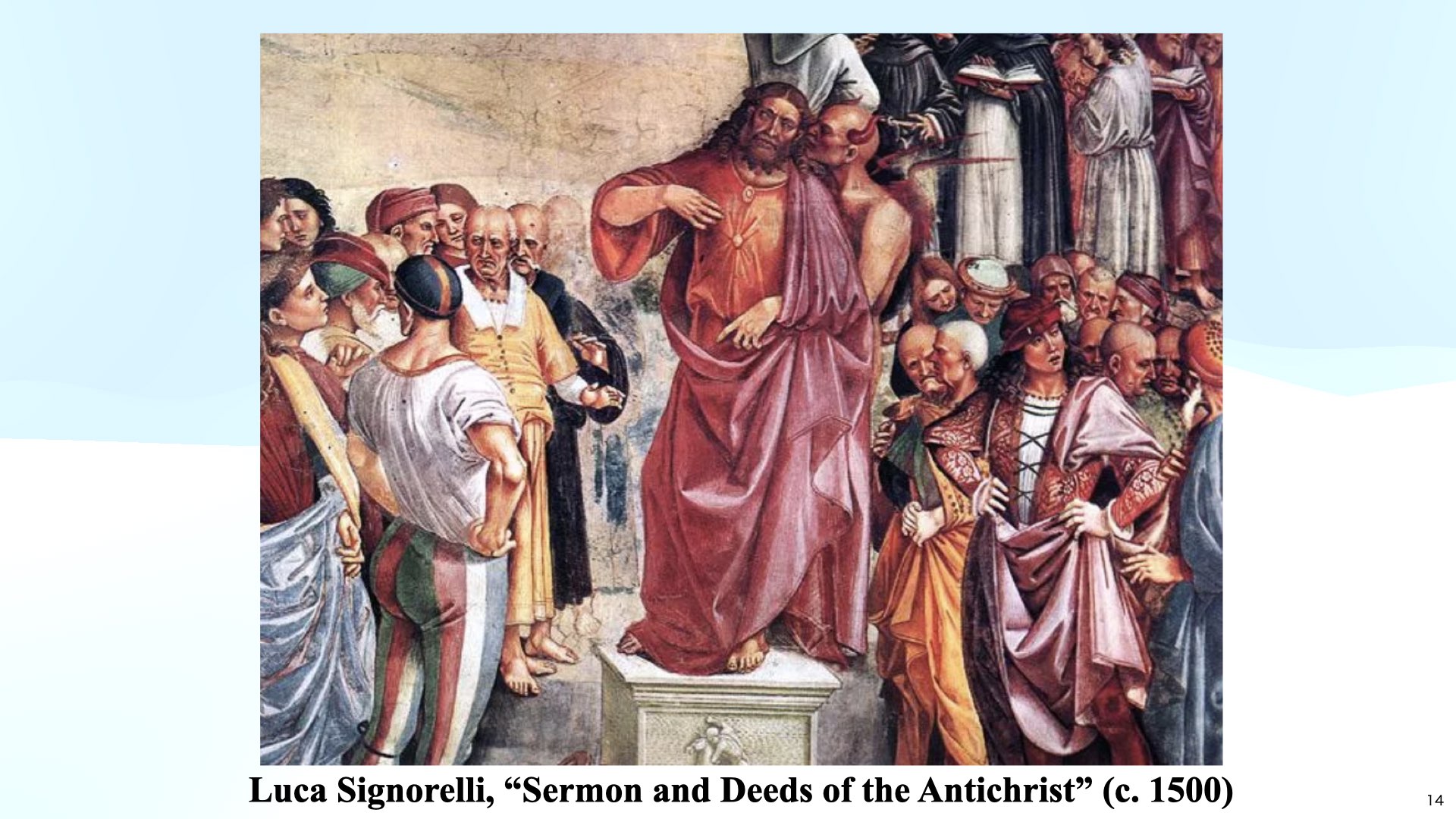

14 ・シニョレッリ(→シニョール・シニョレッリの思い出) |

|

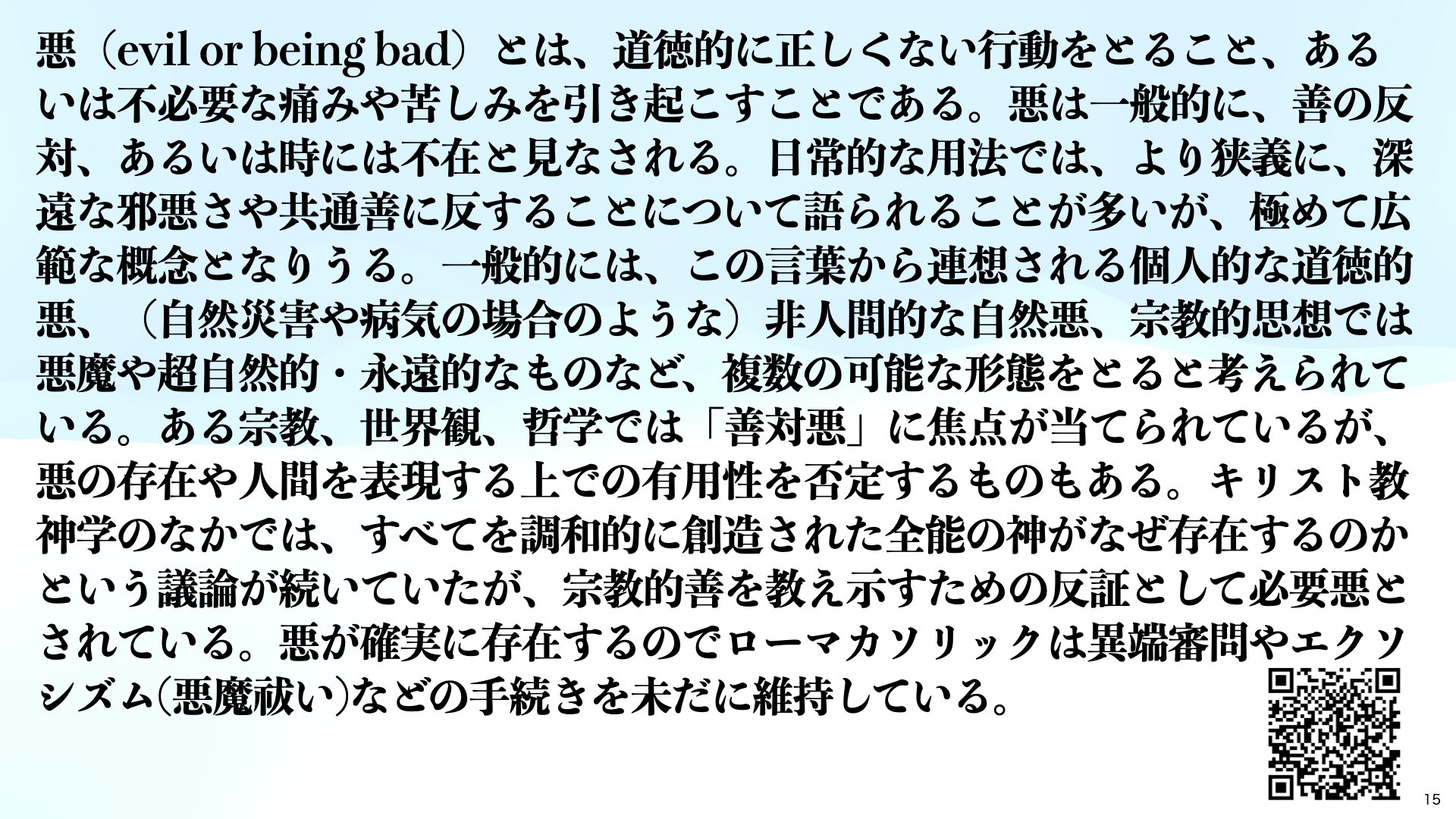

15 ・悪(→悪ないしは邪悪に関するポータルサイト) |

|

16 ・時計仕掛けのオレンジ. |

|

17 |

|

18 |

|

19 ・勧善懲悪 ・『白い巨塔』を人類学する! ・わたしの『がきデカ』論 |

|

20 |

|

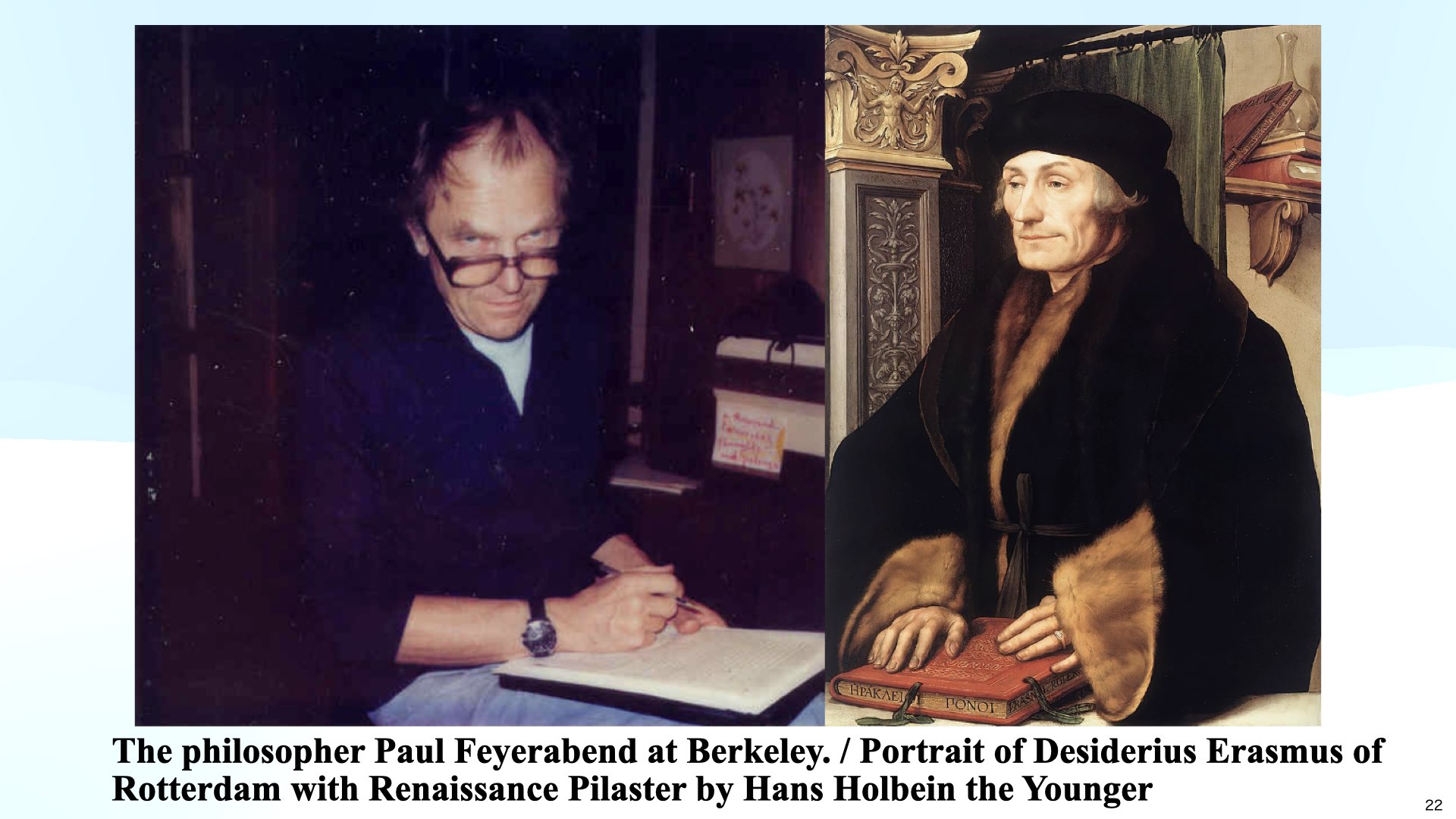

21 ・知的アナキズム(→エピソードIV:新たなる希望はありかな?) ・ポール・ファイアーベント. |

|

22 ・ポール・ファイアーベント. ・エラスムス(→デジデリウス・エラスムス) |

|

23 ●科学研究におけるアナキズム. |

|

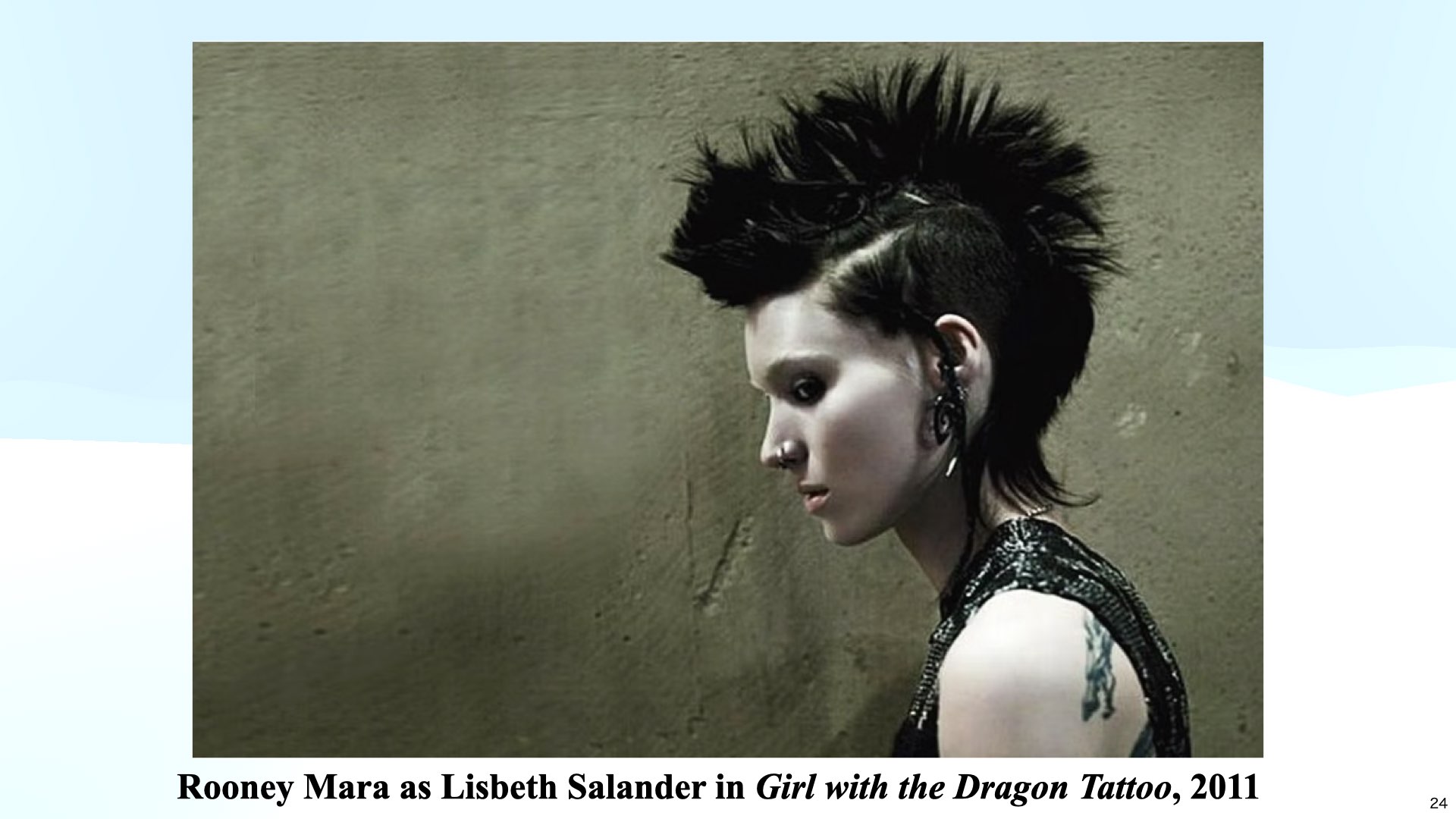

24

「リスベット・サランデル(Lisbeth Salander)

1978年4月30日(ワルプルギスの夜祭りの日)24歳(開始当初)。身長154cm、体重42kg。ミルトン・セキュリティーのフリーの調査員。情報

収集能力に長けており、調査対象の人物の秘密を暴き出す能力がずば抜けて高い。感情表現が乏しい。髪を極端に短く刈り、鼻と眉にピアスを付け、左の肩甲骨

から腰の当たりにかけてドラゴンのタトゥーを、首には長さ2cmのスズメバチのタトゥーを、左の二の腕と足首の周りに帯状のタトゥー等9つ施している。赤

毛の髪を黒に染めている。遠目に見たら痩せぎすの少年と見紛うほど、拒食症のように痩せた青白い肌をしている。

中学校を中退し、高校には進学していないが、映像記憶能力と文章能力が大変優れている。またコンピューターの知識にも優れ、ハッキング能力も高く、英語で

スズメバチを意味する“ワスプ”という名ではハッカー仲間から畏敬の念を抱かれているほど。質問されても何も答えずに黙っているため、責任能力がない精神

異常者の烙印を押され、後見人を付けられるようになる。過去の虐待のトラウマを負っている影響で、敵とみなした人物には容赦なく制裁を加える攻撃的な面を

持つ。

父はソ連時代の情報諜報局GRU元工作員、母は元娼婦という複雑な出自を持つ。幼少時は悲惨な環境の下で暮らし、母が父の家庭内暴力で心身ともに重傷を

負ったことをきっかけに、父への殺害未遂“最悪な出来事”を行ったことで精神病院に隔離された過去を持つ。母は第一部後半で亡くなっている。原作に名前の

み、映画未登場のカミラという双子の妹がいる。

時折ベッドを共にするのはミミや、頭とテクニックのある不特定数。

ミカエルに対し、今まで誰にも抱いたことのない感情を抱き、困惑しながらも恋をしてしまったのだと気づく︎」https://x.gd/Rnh55 |

|

25 ●エピソードIV:新たなる希望はありかな? ・ポスト真実の政治状況 |

|

26 ●学んだことを忘れ去ることの重要性 ●"You mut unlearn what you have learned," my Master said... |

|

27 |

|

28 ・Star Wars: Episode V - I am your Father There are 3 reasons this is a huge twist: 1. Luke realizing his father isn't dead 2. Luke realizing the man he's hated and claimed was evil is actually the one he thought he looked up to. 3. Luke realizing his father is nothing like what he has been told. @YowLife |

|

29 |

|

30 挑戦状 1)ジョークの理解 2)フロイトとユーモア 3)死と悪(→「自殺と死の文化人類学研究」) |

|

31 |

|

32 おしまい ★ベンヤミン「歴史哲学テーゼ」 "The Force is a metaphysical and ubiquitous power in the Star Wars fictional universe. "Force-sensitive" characters use the Force throughout the franchise. Heroes like the Jedi seek to "become one with the Force", matching their personal wills with the will of the Force, while the Sith and other villains exploit the Force and try to bend it toward their own selfish and destructive desires. The Force has been compared to aspects of several world religions, and the phrase "May the Force be with you" has become part of pop culture vernacular." 「フォースは 形而上学的なもので、スター・ウォーズという フィクションの世界ではどこにでもある力だ。「フォースに感応する」キャラクターは、フランチャイズ全体を通してフォースを使用する。ジェダイのような英 雄は「フォースと一体化」しようとし、個人の意志とフォースの意志を一致させようとする。一方、シスやその他の悪役はフォースを悪用し、自分たちの利己的 で破壊的な欲望のためにフォースを曲げようとする。フォースはいくつかの世界宗教の側面と比較され、"May the Force be with you"というフレーズはポップカルチャーの 慣用句の一部となっている。」 |

+++

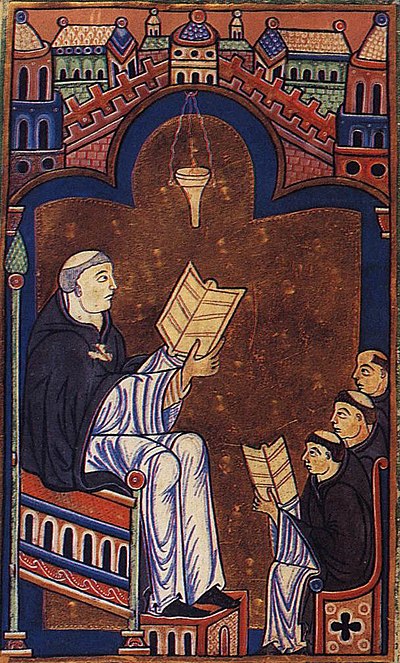

★われわれの師匠:サンヴィクトル のヒューゴ(ヒュー)

Hugo von

Sankt Viktor beim Unterricht in seiner Klosterschule in Paris;

Darstellung aus einem von Hugos Werken; Die Handschrift befindet sich

heute in der Universitätsbibliothek Oxford, England.

| Hugh of

Saint Victor (c. 1096 – 11 February 1141) was a Saxon canon regular

and a leading theologian and writer on mystical theology. Life As with many medieval figures, little is known about Hugh's early life. He was probably born in the 1090s. His homeland may have been Lorraine, Ypres in Flanders, or the Duchy of Saxony.[3] Some sources say that his birth occurred in the Harz district, being the eldest son of Baron Conrad of Blankenburg. Over the protests of his family, he entered the Priory of St. Pancras, a community of canons regular, where he had studied, located at Hamerleve or Hamersleben, near Halberstadt.[4] Due to civil unrest shortly after his entry to the priory, Hugh's uncle, Reinhard of Blankenburg, who was the local bishop, advised him to transfer to the Abbey of Saint Victor in Paris, where he himself had studied theology. He accepted his uncle's advice and made the move at a date which is unclear, possibly 1115–18 or around 1120.[5] He spent the rest of his life there, advancing to head the school.[4] |

聖ヴィクトルのヒュー(1096年頃-1141年2月11日)は、サク

ソン派の正教会司祭であり、神秘主義神学を代表する神学者・著述家である。 生涯[編集] 多くの中世の人物と同様、ヒューの生い立ちについてはほとんど知られていない。おそらく1090年代に生まれたと思われる。ブランケンブルクの コンラート男爵の長男としてハルツ地方で生まれたとする資料もある[3]。家族の反対を押し切り、ハルバースタット近郊のハマーレーヴェまたはハマーシュ レーベンにある聖パンクラス 修道会に入門した。 修道院に入った直後、内乱が起こったため、地元の司教であったヒューの叔父、ブランケンブルクのラインハルトは、彼自身が神学を学んでいたパリのサン・ ヴィクトル修道院に移ることを勧めた。彼は叔父の助言を受け入れ、1115年から18年、あるいは1120年頃と思われるが、その時期ははっきりしない [5]。 |

Works De claustro anime, 14th-century manuscript. Hereford, Cathedral Library, Manuscript collection, P.5.XII. Hugh wrote many works from the 1120s until his death (Migne, Patrologia Latina contains 46 works by Hugh, and this is not a full collection), including works of theology (both treatises and sententiae), commentaries (mostly on the Bible but also including one of pseudo-Dionysius' Celestial Hierarchies), mysticism, philosophy and the arts, and a number of letters and sermons.[6] Hugh was influenced by many people, but chiefly by Saint Augustine, especially in holding that the arts and philosophy can serve theology. Hugh's most significant works include: De sacramentis christianae fidei (On the Mysteries of the Christian Faith/On the Sacraments of the Christian Faith)[7] It is Hugh's most celebrated masterpiece and presents the bulk of Hugh's thoughts on theological and mystical ideas, ranging from God and angels to natural laws. Didascalicon de studio legendi (Didascalicon, or, On the Study of Reading).[8] The subtitle to the Didascalicon, De Studio Legendi, makes the purpose of Hugh's tract clear. Written for the students at the school of Saint Victor, the work is a preliminary introduction to the theological and exegetical studies taught at the Parisian schools, the most advanced centers of learning in Europe in the 12th century. Citing a wide range classical and medieval sources, and with Augustine as his principal authority, Hugh sets forth a comprehensive synthesis of rhetoric, philosophy, and exegesis, designed to serve as a foundation for advanced theological study. The Didascalicon is primarily pedagogical, and not speculative, in nature. It provides the modern reader with a clear sense of the intellectual equipment expected of, if not always fully possessed by, high medieval theologians. In 1125–30, Hugh wrote three treatises structured around Noah's ark: De arca Noe morali (Noah's Moral Ark/On the Moral Interpretation of the Ark of Noah), De arca Noe mystica (Noah's Mystical Ark/On the Mystic Interpretation of the Ark of Noah), and De vanitate mundi (The World's Vanity).[9] De arca Noe morali and De arca Noe mystica reflect Hugh's fascination with both mysticism and the book of Genesis. In Hierarchiam celestem commentaria (Commentary on the Celestial Hierarchy), a commentary on the work by pseudo-Dionysius, perhaps begun around 1125.[10] After Eriugena's translation of Dionysius in the ninth century, there is almost no interest shown in Dionysius until Hugh's commentary.[11] It is possible that Hugh may have decided to produce the commentary (which perhaps originated in lectures to students) because of the continuing (incorrect) belief that the patron saint of the Abbey of Saint Denis, Saint Denis, was to be identified with pseudo-Dionysius. Dionysian thought did not form an important influence on the rest of Hugh's work. Hugh's commentary, however, became a major part of the twelfth and thirteenth-century surge in interest in Dionysius; his and Eriugena's commentaries were often attached to the Dionysian corpus in manuscripts, such that his thought had great influence on later interpretation of Dionysius by Richard of St Victor, Thomas Gallus, Hugh of Balma, Bonaventure and others.[12] Other works by Hugh of St Victor include: In Salomonis Ecclesiasten (Commentary on Ecclesiastes).[13] De tribus diebus (On the Three Days).[14] De sapientia animae Christi.[15] De unione corporis et spiritus (The Union of the Body and the Spirit).[16] Epitome Dindimi in philosophiam (Epitome of Dindimus on Philosophy).[17] Practica Geometriae (The Practice of Geometry).[17] De Grammatica (On Grammar).[17] Soliloquium de Arrha Animae (The Soliloquy on the Earnest Money of the Soul).[18] De contemplatione et ejus speciebus (On Contemplation and its Forms). This is one of the earliest systematic works devoted to contemplation. It appears not to have been written by Hugh himself, but composed by one of his students, possibly from classnotes from his lectures.[19] On Sacred Scripture and its Authors.[20] Various other treatises exist whose authorship by Hugh is uncertain. Six of these are reprinted, in Latin in Roger Baron, ed, Hugues de Saint-Victor: Six Opuscules Spirituels, Sources chrétiennes 155, (Paris, 1969). They are: De meditatione,[21] De verbo Dei, De substantia dilectionis, Quid vere diligendus est, De quinque septenis ,[22] and De septem donis Spiritus sancti[23] De anima is a treatise of the soul: the text will be found in the edition of Hugh's works in the Patrologia Latina of J. P. Migne. Part of it was paraphrased in the West Mercian dialect of Middle English by the author of the Katherine Group.[24] Various other works were wrongly attributed to Hugh in later thought. One such particularly influential work was the Exposition of the Rule of St Augustine, now accepted to be from the Victorine school but not by Hugh of St Victor.[25] A new edition of Hugh's works has been started. The first publication is: Hugonis de Sancto Victore De sacramentis Christiane fidei, ed. Rainer Berndt, Münster: Aschendorff, 2008. |

作品[編集] De claustro anime、14世紀の写本。Hereford, Cathedral Library, Manuscript collection, P.5.XII. ヒューは、1120年代から亡くなるまで、神学(論考と文言)、注釈書(主に聖書に関するものだが、偽ディオニシウスの『天界の階層』の一つも含む)、神 秘主義、哲学、芸術、多くの書簡や説教など、多くの著作を残した[6] 。 ヒューは多くの人々から影響を受けたが、特に芸術と哲学が神学に役立つという点で、聖アウグスティヌスから大きな影響を受けた。 ヒューの最も重要な著作は以下の通りである: De sacramentis christianae fidei(On the Mysteries of the Christian Faith/Onthe Sacraments of the Christian Faith)[7]はヒューの最も有名な代表作であり、神や天使から自然法則に至るまで、神学的・神秘学的思想に関するヒューの考えの大部分を紹介してい る。 Didascalicon de studio legendi』(『ディダスカリコン』あるいは『読書の研究』)[8]『ディダスカリコン』の副題『De Studio Legendi』は、ヒューの小冊子の目的を明確にしている。聖ヴィクトル学校の生徒のために書かれたこの著作は、12世紀のヨーロッパで最も進んだ学問 の中心地であったパリの学校で教えられていた神学と訓詁学の予備的な入門書である。古典と中世の幅広い資料を引用し、アウグスティヌスを主要な典拠とし て、ヒューは修辞学、哲学、釈義学の包括的な統合を打ち出し、高度な神学研究の基礎となるように設計されている。ディダスカリコンは主に教育学的なもので あり、思索的なものではない。現代の読者には、中世の高位の神学者に期待されていた知的装備の明確な感覚を与えてくれる。 1125年から30年にかけて、ヒューはノアの箱舟を中心に構成された3つの論考、『ノアの道徳的箱舟』(De arca Noe morali)、『ノアの神秘的箱舟』(De arca Noe mystica)、『世界の虚栄』(De vanitate mundi)を著した。 [De arca Noe morali』と『De arca Noe mystica』は、ヒューが神秘主義と創世記の両方に魅了されていたことを反映している。 In Hierarchiam celestem commentaria(天界の階層に関する注解)』は、おそらく1125年頃に書かれた偽ディオニュシウスの著作の注解書である[10]。9世紀にエリ ウゲナがディオニュシウスを翻訳した後、ヒューの注解書までディオニュシウスへの関心はほとんど示されていない。 [11]ヒューは、サン・ドニ修道院の守護聖人である聖ドニが偽ディオニュシウスと同一視されるという(誤った)信念が続いていたため、(おそらく学生へ の講義に端を発する)注釈書の作成を決意した可能性がある。ディオニュソス思想は、ヒューの他の著作に重要な影響を与えることはなかった。しかし、ヒュー の注釈書は、12世紀から13世紀にかけてのディオニュシオスへの関心の高まりの主要な部分となった。彼とエリウゲナの注釈書は、写本においてしばしば ディオニュシオス・コーパスに付されており、彼の思想は、聖ヴィクトルのリチャード、トマス・ガルス、バルマのヒュー、ボナヴェントゥールなどによる後の ディオニュシオス解釈に大きな影響を与えた[12]。 聖ヴィクトルのヒューによる他の著作には以下のものがある: In Salomonis Ecclesiasten(伝道の書の注解)[13]。 De tribus diebus(三日について)[14]。 De sapientia animae Christi(キリストの霊性)[15]。 De unione corporis et spiritus(肉体と精神の結合)[16]。 Epitome Dindimi in philosophiam(哲学におけるディンディムスの叙事詩)[17]。 幾何学の実践』(Practica Geometriae)[17]。 De Grammatica(文法について)[17]。 Soliloquium de Arrha Animae(魂の切実な金銭に関する独白)[18]。 De contemplatione et ejus speciebus(観想とその形式について)。これは観想に捧げられた最も初期の体系的著作のひとつである。ヒュー自身によって書かれたものではなく、 彼の弟子の一人によって、おそらく彼の講義のクラスノートから構成されたものと思われる[19]。 聖典とその著者について』[20]。 このほかにも、ヒューの作者かどうか定かでないさまざまな論考が存在する。そのうちの6冊は、Roger Baron, ed,Hugues de Saint-Victor.にラテン語で再版されている: Six Opuscules Spirituels,Sources chrétiennes155, (Paris, 1969)にラテン語で再録されている。それらは以下の通りである: De meditatione,[21] De verbo Dei,De substantia dilectionis,Quid vere diligendus est,De quinque septenis ,[22]andDe septem donis Spiritus sancti[23]である。 De anima』は魂についての論考で、J. P. Migneの『Patrologia Latina』所収のヒュー著作集にテキストがある。その一部はキャサリン・グループの著者によって中世英語の西メルキア方言で言い換えられた[24]。 他にもさまざまな著作が、後世の思想において誤ってヒューの著作とされた。そのような特に影響力のある著作のひとつが『聖アウグスティヌスの規則の解説』 であり、現在では聖ヴィクトールのヒューによるものではなく、ヴィクトール派のものであると認められている[25]。 ヒューの著作の新しい版が始まった。最初の出版物は、Hugonis de Sancto Victore De sacramentis Christiane fideiである。Rainer Berndt, Münster: Aschendorff, 2008. |

| Philosophy and theology The early Didascalicon was an elementary, encyclopedic approach to God and Christ, in which Hugh avoided controversial subjects and focused on what he took to be commonplaces of Catholic Christianity. In it he outlined three types of philosophy or "science" [scientia] that can help mortals improve themselves and advance toward God: theoretical philosophy (theology, mathematics, physics) provides them with truth, practical philosophy (ethics, economics, politics) aids them in becoming virtuous and prudent, and "mechanical" or "illiberal" philosophy (e.g., carpentry, agriculture, medicine) yields physical benefits. A fourth philosophy, logic, is preparatory to the others and exists to ensure clear and proper conclusions in them. Hugh's deeply mystical bent did not prevent him from seeing philosophy as a useful tool for understanding the divine, or from using it to argue on behalf of faith. Hugh was heavily influenced by Augustine's exegesis of Genesis. Divine Wisdom was the archetypal form of creation. The creation of the world in six days was a mystery for man to contemplate, perhaps even a sacrament. God's forming order from chaos to make the world was a message to humans to rise up from their own chaos of ignorance and become creatures of Wisdom and therefore beauty. This kind of mystical-ethical interpretation was typical for Hugh, who tended to find Genesis interesting for its moral lessons rather than as a literal account of events. Along with Jesus, the sacraments were divine gifts that God gave man to redeem himself, though God could have used other means. Hugh separated everything along the lines of opus creationis and opus restaurationis. Opus Creationis was the works of the creation, referring to God's creative activity, the true good natures of things, and the original state and destiny of humanity. The opus restaurationis was that which dealt with the reasons for God sending Jesus and the consequences of that. Hugh believed that God did not have to send Jesus and that He had other options open to Him. Why he chose to send Jesus is a mystery we are to meditate on and is to be learned through revelation, with the aid of philosophy to facilitate understanding. |

哲学と神学[編集] 初期の『ディダスカリコン』は、神とキリストについての初歩的で百科事典的なアプローチであり、ヒューは論争的なテーマを避け、カトリック・キリスト教の 一般的な事柄に焦点を当てた。理論哲学(神学、数学、物理学)は真理を提供し、実践哲学(倫理学、経済学、政治学)は高潔で思慮深い人間になることを助 け、"機械的 "あるいは "非自由主義的 "哲学(大工、農業、医学など)は肉体的な利益をもたらす。第4の哲学である論理学は、他の哲学の準備的なものであり、それらの哲学において明確で適切な 結論を得るために存在する。ヒューの深い神秘主義的傾向は、哲学を神を理解するための有用な道具と見なしたり、信仰を代弁するために哲学を用いることを妨 げなかった。 ヒューはアウグスティヌスの創世記釈義に大きな影響を受けた。神の知恵は創造の原型であった。6日間で世界が創造されたことは、人間にとって思索すべき神 秘であり、おそらくは秘跡ですらあった。神が混沌から秩序を形成して世界を創造したことは、人間に対して、自らの無知という混沌から立ち上がり、叡智、ひ いては美の被造物となるようにというメッセージであった。このような神秘主義的・倫理的な解釈は、創世記を文字通りの出来事としてではなく、道徳的な教訓 として興味深く捉える傾向があったヒューの典型的な解釈であった。 イエスとともに、秘跡は神が人間に与えた神の賜物であり、神は他の手段を用いることもできたが、自らを救済するために与えた。ヒューは、すべてを「創造と 救済の作品(opus creationis)」と「創造と救済の作品(opus restaurationis)」に分けて考えた。Opus Creationisは被造物の業であり、神の創造的活動、物事の真の善い性質、人間の本来の状態や運命を指していた。 Opusrestaurationisは、神がイエスを遣わされた理由とその結果を扱うものであった。ヒューは、神がイエスを遣わす必要はなく、神には他 の選択肢があると信じていた。神がなぜイエスを遣わすことを選んだのかは、私たちが黙想すべき謎であり、理解を容易にするために哲学の助けを借りながら、 啓示を通して学ぶべきものである。 |

| Legacy Within the Abbey of St Victor, many scholars who followed him are often known as the 'School of St Victor'. Andrew of St Victor studied under Hugh.[26] Others, who probably entered the community too late to be directly educated by Hugh, include Richard of Saint Victor and Godfrey.[27] One of Hugh's ideals that did not take root in St Victor, however, was his embracing of science and philosophy as tools for approaching God.[citation needed] His works are in hundreds of libraries all across Europe.[citation needed] He is quoted in many other publications after his death,[citation needed] and Bonaventure praises him in De reductione artium ad theologiam. He was also an influence on the critic Erich Auerbach, who cited this passage from Hugh of St Victor in his essay "Philology and World Literature":[28] It is therefore, a source of great virtue for the practiced mind to learn, bit by bit, first to change about in visible and transitory things, so that afterwards it may be able to leave them behind altogether. The person who finds his homeland sweet is a tender beginner; he to whom every soil is as his native one is already strong; but he is perfect to whom the entire world is as a foreign place. The tender soul has fixed his love on one spot in the world; the strong person has extended his love to all places; the perfect man has extinguished his. |

遺産[編集] 聖ヴィクトル修道院の中で、彼に従った多くの学者たちはしばしば「聖ヴィクトル学派」として知られている。聖ヴィクトルのアンドリューはヒューに師事した [26]。聖ヴィクトルのリチャードやゴッドフリーなど、ヒューから直接教育を受けるには遅すぎたと思われる者もいる[27]。 彼の著作はヨーロッパ中の何百もの図書館に所蔵されている[要出典]。死後も多くの出版物に引用され[要出典]、ボナヴェントゥールは『神学への還元』 (De reductione artium ad theologiam)の中で彼を称賛している。 また、彼は批評家エーリッヒ・アウエルバッハにも影響を与え、彼のエッセイ「言語学と世界文学」の中で聖ヴィクトルのヒューのこの一節を引用している [28]。 それゆえ、修練を積んだ心にとって、まず目に見えるもの、一過性のものから少しずつ変化していくことを学ぶことは、大きな美徳の源である。自分の故郷を甘 いと感じる人は優しい初心者であり、あらゆる土壌が自分の生まれ故郷のようになる人はすでに強い。優しい魂は世界の一か所に愛を固定し、強い人はあらゆる 場所に愛を広げ、完全な人は愛を消滅させる。 |

| Works Modern editions Latin text Latin texts of Hugh of St. Victor are available in the Migne edition at Documenta Catholica Omnia, http://www.documentacatholicaomnia.eu/30_10_1096-1141-_Hugo_De_S_Victore.html Henry Buttimer, Hugonis de Sancto Victore. Didascalicon. De Studio Legendi (Washington, DC: Catholic University Press, 1939). Hugh of St Victor, L'oeuvre de Hugues de Saint-Victor. 1. De institutione novitiorum. De virtute orandi. De laude caritatis. De arrha animae, Latin text edited by H.B. Feiss & P. Sicard; French translation by D. Poirel, H. Rochais & P. Sicard. Introduction, notes and appendices by D. Poirel (Turnhout, Brepols, 1997) Hugues de Saint-Victor, L'oeuvre de Hugues de Saint-Victor. 2. Super Canticum Mariae. Pro Assumptione Virginis. De beatae Mariae virginitate. Egredietur virga, Maria porta, edited by B. Jollès (Turnhout: Brepols, 2000) Hugo de Sancto Victore, De archa Noe. Libellus de formatione arche, ed Patricius Sicard, CCCM vol 176, Hugonis de Sancto Victore Opera, I (Turnhout: Brepols, 2001) Hugo de Sancto Victore, De tribus diebus, ed Dominique Poirel, CCCM vol 177, Hugonis de Sancto Victore Opera, II (Turnhout: Brepols, 2002) Hugo de Sancto Victore, De sacramentis Christiane fidei, ed. Rainer Berndt (Münster: Aschendorff, 2008) Hugo de Sancto Victore, Super Ierarchiam Dionysii, CCCM vol 178, Hugonis de Sancto Victore Opera, III (Turnhout: Brepols, forthcoming) English translations Hugh of St Victor, Explanation of the Rule of St. Augustine, translated by Aloysius Smith (London, 1911) Hugh of St Victor, The Soul's Betrothal-Gift, translated by FS Taylor (London, 1945) [translation of De Arrha Animae] Hugh of St Victor, On the sacraments of the Christian faith: (De sacramentis), translated by Roy J Deferrari (Cambridge, MA: Mediaeval Academy of America, 1951) Hugh of Saint-Victor: Selected spiritual writings, translated by a religious of C.S.M.V.; with an introduction by Aelred Squire. (London: Faber, 1962) [reprinted in Eugene, Oregon: Wipf & Stock Publishers, 2009] [contains a translation of the first four books of De arca Noe morali and the first two (of four) books of De vanitate mundi]. The Didascalicon of Hugh of St. Victor, translated by Jerome Taylor (New York and London: Columbia U. P., 1961) [reprinted 1991] [translation of the Didascalicon] Soliloquy on the Earnest Money of the Soul, trans Kevin Herbert (Milwaukee, WI: Marquette University Press, 1984) [translation of Soliloquium de Arrha Animae] Hugh of St Victor, Practica Geometriae, trans. Frederick A Homann (Milwaukee: Marquette University Press, 1991) Hugh of St Victor, extracts from Introductory Notes on the Scriptures and on the Scriptural Writers, trans Denys Turner, in Denys Turner, Eros and Allegory: Medieval Exegesis of the Song of Songs (Kalamazoo, MI: Cistercian Publications, 1995), 265-274 Hugh of Saint Victor on the Sacraments of the Christian Faith, trans Roy Deferrari (Eugene, Oregon: Wipf & Stock Publishers, 2007) [translation of De Sacramentis Christianae Fidei] Boyd Taylor Coolman and Dale M Coulter, eds, Trinity and creation: a selection of works of Hugh, Richard and Adam of St Victor (Turnhout: Brepols, 2010) [includes translation of Hugh of St Victor, On the Three Days and Sentences on Divinity] Hugh Feiss, ed, On love: a selection of works of Hugh, Adam, Achard, Richard and Godfrey of St Victor (Turnhout: Brepols, 2011) [includes translations of The Praise of the Bridegroom, On the Substance of Love, On the Praise of Charity, What Truly Should be Loved?, On the Four Degrees of Violent Love, trans. A.B. Kraebel, and Soliloquy on the Betrothal-Gift of the Soul] Franklin T. Harkins and Frans van Liere, eds, Interpretation of scripture: theory. A selection of works of Hugh, Andrew, Richard and Godfrey of St Victor, and of Robert of Melun (Turnhout, Belgium: Brepols, 2012) [contains translations of: Didascalion on the study of reading, introduced and translated by Franklin T Harkins; On Sacred Scripture and its authors and The diligent examiner, introduced and translated by Frans van Liere; On the sacraments of the Christian faith, prologues, introduced and translated by Christopher P Evans] The Compendium of Philosophy (Compendium Philosophiae) attributed to Hugh of St Victor in several medieval manuscripts, upon rediscovery and examination in the 20th century, has turned out to have actually been a recension of William of Conches's De Philosophia Mundi.[29][30] |

作品[編集] 現代版[編集] ラテン語テキスト 聖ヴィクトールのヒューのラテン語テキストは、Documenta Catholica Omnia,http://www.documentacatholicaomnia.eu/30_10_1096-1141-_Hugo_De_S_Victore.html のMigne版で入手できる。 Henry Buttimer,Hugonis de Sancto Victore. Didascalicon. De Studio Legendi(Washington, DC: Catholic University Press, 1939). Hugh of St Victor,L'oeuvre de Hugues de Saint-Victor. 1. De institutione novitiorum. De virtute orandi. De laude caritatis. De arrha animae, ラテン語テキスト:H.B. Feiss & P. Sicard 編; フランス語翻訳:D. Poirel, H. Rochais & P. Sicard. 序、注、付録:D. Poirel (Turnhout, Brepols, 1997) Hugues de Saint-Victor,L'oeuvre de Hugues de Saint-Victor. 2. Super Canticum Mariae. Pro Assumptione Virginis. De beatae Mariae virginitate. Egredietur virga, Maria porta, edited by B. Jollès (Turnhout: Brepols, 2000) Hugo de Sancto Victore,De archa Noe. Libellus de formatione arche, ed Patricius Sicard, CCCM vol.176, Hugonis de Sancto Victore Opera, I (Turnhout: Brepols, 2001). Hugo de Sancto Victore,De tribus diebus, ed Dominique Poirel, CCCM vol 177, Hugonis de Sancto Victore Opera, II (Turnhout: Brepols, 2002). Hugo de Sancto Victore,De sacramentis Christiane fidei, ed. (Turnout: Breols, 2002). Rainer Berndt (Münster: Aschendorff, 2008) Hugo de Sancto Victore,Super Ierarchiam Dionysii, CCCM vol 178, Hugonis de Sancto Victore Opera, III (Turnhout: Brepols, 近刊) 英訳 聖ヴィクトールのヒュー、聖アウグスティヌスの規則の説明、アロイシウス・スミス訳(ロンドン、1911年) 聖ヴィクトールのヒュー『魂の婚約贈与』FSテイラー訳(ロンドン、1945年)[『デ・アルハ・アニマエ』の翻訳] 聖ヴィクトールのヒュー、キリスト教信仰の秘跡について:(De sacramentis)、ロイ・J・デフェラーリ訳(Cambridge, MA: Mediaeval Academy of America, 1951) サン=ヴィクトールのヒュー C.S.M.V.の修道者が翻訳した霊的著作集。(London: Faber, 1962) [reprinted in Eugene, Oregon: Wipf & Stock Publishers, 2009] [De arca Noe moraliの最初の4冊とDe vanitate mundiの最初の2冊(4冊のうち)の翻訳を含む]。 The Didascalicon of Hugh of St. Victor, translated by Jerome Taylor (New York and London: Columbia U. P., 1961) [reprinted 1991] [ディダスカリコンの翻訳]. ケヴィン・ハーバート訳『魂の切実な金銭についての独り言』(ウィスコンシン州ミルウォーキー:マーケット大学出版、1984年) [Soliloquium de Arrha Animaeの翻訳] Hugh of St Victor,Practica Geometriae, trans. フレデリック・A・ホーマン (Milwaukee: Marquette University Press, 1991) Hugh of St Victor, extracts fromIntroductory Notes on the Scriptures and on the Scriptural Writers, trans Denys Turner, in Denys Turner,Eros and Allegory: 中世の歌の釈義(Kalamazoo, MI: Cistercian Publications, 1995), 265-274 Hugh of Saint Victor on the Sacraments of the Christian Faith, trans Roy Deferrari (Eugene, Oregon: Wipf & Stock Publishers, 2007) [De Sacramentis Christianae Fideiの翻訳]. ボイド・テイラー・クールマン、デール・M・コールター編『三位一体と創造:聖ヴィクトルのヒュー、リチャード、アダム著作選集』(Turnhout: Brepols, 2010)[聖ヴィクトルのヒュー『三日について』と『神性についての文章』の翻訳を含む]。 Hugh Feiss, ed,On love: a selection of works of Hugh, Adam, Achard, Richard and Godfrey of St Victor(Turnhout: Brepols, 2011) [including translations ofThe Praise of the Bridegroom,On the Substance of Love,On the Praise of Charity,What Truly Should be Loved?,On the Four Degrees of Violent Love,trans. A.B.クレーベル訳)、「魂の婚約贈与に関する独白」(フランクリン・T・ハーキンズ、A.B.クレーベル訳)である。 フランクリン・T・ハーキンズ、フランズ・ファン・リエール編『聖典の解釈:理論』。A selection of works of Hugh, Andrew, Richard and Godfrey of St Victor, and Robert of Melun(Turnhout, Belgium: Brepols, 2012) [contains translations of: フランクリン・T・ハーキンズが紹介・翻訳した「読書学に関するディダスカリオン」、フランズ・ファン・リエールが紹介・翻訳した「聖典とその著者につい て」、クリストファー・P・エヴァンズが紹介・翻訳した「 キリスト教信仰の秘跡について」の翻訳を含む。] 中世のいくつかの写本で聖ヴィクトルのヒューの著作とされている『哲学大系』(Compendium Philosophiae)は、20世紀に再発見され、検討された結果、実際にはコンシュのウィリアムの『De Philosophia Mundi』の再版であったことが判明した[29][30]。 |

| Art of memory § Principles,

where Hugh's Didascalicon and Chronica are referred to. Hendrik Mande The Mystic Ark, painting by Hugh |

ヒューの『ディダスカリコン』と『クロニカ』が参照されている。 ヘンドリック・マンデ 神秘の方舟、ヒューの絵 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hugh_of_Saint_Victor |

★

特別附録:続きは「悪ないしは邪悪に関するポータルサイト」でご覧ください。

リ ンク

文 献(※この文献リストで感じるのは、これまでの悪についての哲学者や思想家の著名な著者名が出てこないことである→「悪の定義の難しさ」)

そ の他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆